Introduction

Myxozoans are a diverse group of metazoan parasites within the phylum Cnidaria that infect both marine and freshwater fish hosts (Eiras, Reference Eiras2005; Bartholomew et al, Reference Bartholomew, Atkinson, Hallett, Lowenstine, Garner, Gardiner, Rideout, Keel and Brown2008; Hartigan et al, Reference Hartigan, Fiala, Dyková, Rose, Phalen and Šlapeta2012; Okamura et al, Reference Okamura, Hartigan and Naldoni2018). A total of 2,600 nominal myxozoan species have been identified, which accounts for about 23% of the cnidarian species diversity (Lom and Dyková, Reference Lom and Dyková2006). Myxozoan infections are mostly harmful; they can leave lesions in the host tissue, which affect fish growth, survival and meat quality (Baldwin et al, Reference Baldwin, Vincent, Silflow and Stanek2000; Videira et al, Reference Videira, Velasco, Malcher, Santos, Matos and Matos2016; Holzer et al, Reference Holzer, Piazzon, Barrett, Bartholomew and Sitjà-Bobadilla2021). Notably, some myxozoan species are responsible for tremendous damage to fish aquaculture (Chilmonczyk et al, Reference Chilmonczyk, Monge and De Kinkelin2002; Sarker et al, Reference Sarker, Kallert, Hedrick and El-Matbouli2015).

Myxidium Bütschli, 1882 is the third most specious myxozoan genus with 232 nominal species, which are mostly coelozoic and rarely histozoic (Eiras et al, Reference Eiras, Saraiva, Cruz, Santos and Fiala2011). Morphologically, species of this genus are characterized by fusiform myxospores, straight or slightly crescent, or even sigmoid with more or less pointed ends. Their two polar capsules are mostly pyriform and located at each end of the myxospore (Lom and Dyková, Reference Lom and Dyková2006; Fiala and Bartosová, Reference Fiala and Bartosová2010; Eiras et al, Reference Eiras, Saraiva, Cruz, Santos and Fiala2011; Heiniger and Adlard, Reference Heiniger and Adlard2014; Baiko et al, Reference Baiko, Lisnerová, Bartošová-Sojková, Holzer, Blabolil, Schabuss and Fiala2024). This myxospore-based taxonomy is, however, recognized to be artificial and multiple studies have acknowledged the challenges in distinguishing Myxidium from Zschokkella (Lom and Dyková, Reference Lom and Dyková2006; Fiala and Bartosová, Reference Fiala and Bartosová2010; Heiniger and Adlard, Reference Heiniger and Adlard2014; Chen et al, Reference Chen, Yang and Zhao2020; McAllister et al, Reference McAllister, Cloutman, Leis and Robison2022; Baiko et al, Reference Baiko, Lisnerová, Bartošová-Sojková, Holzer, Blabolil, Schabuss and Fiala2024). It has been established that the morphological characteristics of the genus Myxidium overlap with those of the genus Zschokkella, with which Myxidium shares close morphometric traits such as similar spore shape, as well as similar tissue specificity (i.e., the presence of mostly coelozoic and rarely histozoic plasmodia). Specifically, Zschokkella myxospores are defined as ellipsoidal in sutural view and slightly bent or semicircular in valvular view, with rounded or bluntly pointed ends, which overlaps with the description of several Myxidium species. Moreover, the two polar capsules of Zschokkella are almost spherical and open slightly sub-terminally and both to one side (Lom and Dyková, Reference Lom and Dyková2006; Eiras et al, Reference Eiras, Saraiva, Cruz, Santos and Fiala2011). Both genera can present either smooth or striated shell valves, as well as straight, curved or sinuous suture line. Accordingly, molecular studies have shown that the genera Myxidium and Zschokkella are polyphyletic and often closely related (Fiala and Bartosová, Reference Fiala and Bartosová2010; Heiniger and Adlard, Reference Heiniger and Adlard2014; Freeman and Kristmundsson, Reference Freeman and Kristmundsson2015, Reference Freeman and Kristmundsson2018; Rocha et al, Reference Rocha, Azevedo, Oliveira, Â, Antunes, Rodrigues and Casal2019; Chen et al, Reference Chen, Yang and Zhao2020; McAllister et al, Reference McAllister, Cloutman, Leis and Robison2022; Baiko et al, Reference Baiko, Lisnerová, Bartošová-Sojková, Holzer, Blabolil, Schabuss and Fiala2024; Vieira et al, Reference Vieira, Osaki-Pereira, Abdallah, Oliveira, Duarte, da Silva Rj and de Azevedo2024).

The name ‘barbs’ refers to a diverse, paraphyletic assemblage of cyprinid fishes that were historically grouped under Barbus sensu lato (Durand et al, Reference Durand, Tsigenopoulos, Unlü and Berrebi2002; Tsigenopoulos et al, Reference Tsigenopoulos, Ráb, Naran and Berrebi2002, Reference Tsigenopoulos, Kasapidis and Berrebi2010; Geiger et al., Reference Geiger, Herder, Monaghan, Almada, Barbieri, Bariche, Berrebi, Bohlen, Casal-Lopez, Delmastro and Denys2014; Yang et al, Reference Yang, Sado, Vincent Hirt, Pasco-Viel, Arunachalam, Li, Wang, Freyhof, Saitoh, Simons, Miya, He and Mayden2015). Three barb species found in the Sea of Galilee are native to the Jordan River Basin: Capoeta damascina (Valenciennes, 1842), Carasobarbus canis (Valenciennes, 1842) and Luciobarbus longiceps (Valenciennes, 1842) (Goren, Reference Goren1974). Interestingly, archaeological remains from the middle Pleistocene indicate that these species are among the first to have been cooked by hominins (Zohar et al, Reference Zohar, Alperson-Afil, Goren-Inbar, Prévost, Tütken, Sisma-Ventura, Hershkovitz and Najorka2022). To date, 14 Myxidium species have been described globally from barbs (Eiras et al, Reference Eiras, Saraiva, Cruz, Santos and Fiala2011; Fariya et al, Reference Fariya, Kaur and Abidi2020). Although barbs from the Sea of Galilee are a source of food (Gophen, Reference Gophen1986) no myxozoans have yet been described from these hosts in this water body. Overall, the myxozoan parasites present in the Sea of Galilee have been understudied (Landsberg, Reference Landsberg1985, Reference Landsberg1987; Lövy et al, Reference Lövy, Smirnov, Brekhman, Ofek and Lotan2018; Gupta et al, Reference Gupta, Haddas-Sasson, Gayer and Huchon2022).

The Sea of Galilee is part of the Jordan River basin, a geographically and ecologically distinct freshwater system spanning Israel, Jordan and Syria (Goren, Reference Goren1974; Goren and Ortal, Reference Goren and Ortal1999; Borkenhagen and Krupp, Reference Borkenhagen and Krupp2013). This basin supports a diverse ichthyofauna, including both endemic and several introduced fish species (Goren, Reference Goren1974; Krupp and Schneider, Reference Krupp and Schneider1989; Goren and Ortal, Reference Goren and Ortal1999). The high level of endemism of the fish fauna underscores the ecological uniqueness of the Jordan River basin and highlights the importance of understanding parasitic infections within this unique system. Parasite–host interactions in such systems can provide valuable insights into host–parasite dynamics and the potential vulnerability of native species to parasitic threats (Marcogliese, Reference Marcogliese2016; Penczykowski et al, Reference Penczykowski, Laine and Koskella2015). Herein, we describe two novel Myxidium species from the Sea of Galilee, M. grauri n. sp. and M. sharmai n. sp. isolated from the gallbladder of the barbs, C. canis and L. longiceps, respectively, based on morphological and molecular data.

Material and methods

Collection and morphological identification

Specimens of Carasobarbus canis vern. Jordan himri (n = 45) and Luciobarbus longiceps vern. Jordan barbel (n = 20) with an average length of 12–15 cm were collected from the Sea of Galilee, Israel, on 26 October 2022, and were transported to the lab as fresh samples. The sampling of the fish was performed under the authorization of the Fisheries and Aquaculture Department of the Israeli Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (authorization provided on 11 November 2020). Fish specimens were carefully examined externally under a stereomicroscope for the presence of plasmodia, followed by dissection. Plasmodia identified in the gallbladder bile were teased apart on clean glass slides, and fresh myxospores were photographed using a compound microscope equipped with a Nikon DS-Ri2 imaging system. The myxospores were stained with freshly prepared Ziehl–Neelsen and Giemsa stain. Measurements were conducted on 50 fresh myxospores (Lom and Dyková, Reference Lom, Dyková, Lom and Dyková1992).

DNA isolation and 18S rRNA amplification

For the molecular work, a few plasmodia were fixed in absolute alcohol and stored at −20˚C until further use. The extraction of genomic DNA was performed using the Qiagen (Hilden, Germany) DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit following the manufacturer’s instructions. PCR amplification of the 18S rRNA was done on one large plasmodium using universal and Myxozoa-specific primers (Table 1). A part of the same plasmodium was also used for microscopical analysis. The 25 µL of PCR mix consisted of 1 μL of DNA template (∼100 ng and ∼6 ng for M. grauri n. sp. and M. sharmai n. sp., respectively), 2.5 μL of 10X Ex Taq buffer with Mg2+ (Takara Bio Inc., Japan), 0.2 μL of Ex Taq polymerase (5 U/μL; Takara Bio Inc., Japan), 2 μL of 20 µM dNTP mix (Takara Bio Inc., Japan), 2.5 μL of each primer at 5 pmol/μL (Merck, Germany), 0.2 μL of DMSO (100%, Sigma Aldrich, USA), 5 μL of 5 M Betaine (Bio-Lab Ltd., Jerusalem) and 9.1 μL of molecular grade water. Amplification was done using an initial denaturation at 94ºC for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94ºC for 45 s, annealing of primers at 58ºC for 45 s, and extension at 72 ºC for 2 min. The final extension was at 72 ºC for 10 min. The PCR products were cleaned from primers using the ExoSAP method (Bell, Reference Bell2008). Sequencing was performed on an ABI 3500xl Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems™, Waltham, MA, USA) by the DNA sequencing Unit at Tel-Aviv University. Chromatograms were assembled and primers were removed using Geneious Prime 2023. As hosts may harbour multiple myxozoan parasites, we carefully analysed the resulting chromatograms, searching for the presence of noisy abnormal peaks. Abnormal peaks can originate from a mixture of 18S rRNA sequences from more than one species, suggesting contamination. We did not observe such peaks in any of our sequences.

Table 1. PCR primers used for the amplification and sequencing of the 18S rRNA gene and for the fish barcoding

Taxonomic identification of the fish host

The taxonomic identification of the fish host was initially conducted by a colleague, Mr Kfir Gayer, based on external morphological characteristics. To confirm this identification, the cytochrome oxidase subunit I (COI) barcoding marker was sequenced. DNA was extracted from fish muscle tissues as indicated above. The amplification of the COI gene was performed with the primers VF2_t1_short and FishR2_t1_short (Table 1). The 25 µL of PCR mix consisted of 1 μL of DNA template (∼100 ng), 2.5 μL of 10X Ex Taq buffer with Mg2+ (Takara Bio Inc., Japan), 0.2 μL of Ex Taq polymerase (5 U/μL; Takara Bio Inc., Japan), 2 μL of 20 µM dNTP mix (Takara Bio Inc., Japan), 2.5 μL of each primer at 5 pmol/μL (Merck, Germany), 0.5 μL of DMSO (100%, Sigma Aldrich, USA) and 13.8 μL of molecular-grade water. The PCR products were cleaned and sequenced as described above, using the amplification primers. The morphological identification was then validated using the BOLD Identification Engine (http://www.boldsystems.org/index.php/IDS_OpenIdEngine) with the obtained COI sequence. In both cases, the obtained sequences matched the expected reference sequences in public databases.

Phylogenetic reconstructions

To reconstruct the myxozoan phylogenetic tree based on 18S rRNA sequences, we first downloaded all sequences from the biliary tract IV lineage, as reported by Holzer et al (Reference Holzer, Bartošová-Sojková, Born-Torrijos, Lövy, Hartigan and Fiala2018). This lineage, which includes freshwater members of the genus Myxidium, also comprises species from the genera Zschokkella, Myxobolus, Chloromyxum, Cystodiscus, Soricimyxum and Sphaeromyxa (Holzer et al, Reference Holzer, Bartošová-Sojková, Born-Torrijos, Lövy, Hartigan and Fiala2018). To expand this dataset with more recent sequences, we performed BLASTn searches against the NCBI database (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) on May 30, 2024, using 6 diverse sequences from the biliary tract IV lineage and the newly obtained sequences. This search yielded a total of 602 myxozoan sequences. We then removed redundant identical sequences, sequences shorter than 1,000 bp, and sequences that do not belong to the biliary tract IV lineage. For species represented by multiple sequences, we manually selected five of the longest and most divergent sequences. Only two representatives of the genus Sphaeromyxa were included, Sphaeromyxa zaharoni (OY751524) and Sphaeromyxa hellandi (DQ377692), and were used as outgroup taxa. The final alignment included 102 sequences, incorporating the two newly identified Myxidium species. We note that because our BLASTn searches identified divergent sequences outside the biliary tract IV lineage (which were filtered), we hypothesize that most lineages within this clade were detected. However, it is possible that some highly divergent biliary tract IV lineage 18S rRNA sequences were missed by this search procedure.

Prior to alignment, the first and last 20 bp of each downloaded sequence were removed, as Myxozoan 18S rRNA sequences are often deposited with primer sequences. The web server GUIDANCE2 (Sela et al, Reference Sela, Ashkenazy, Katoh and Pupko2015) was used to align sequences and filter out ambiguously aligned positions. Alignment was performed using the MAFFT algorithm with the parameters Max-Iterate: 1000 and Pairwise Alignment Method: localpair. Positions with a Guidance score below 0.93 were excluded. In addition, positions containing more than 50% missing data were also excluded using the ‘mask alignment’ options of Geneious Prime 2024. The final dataset comprised 1,716 positions.

Phylogenetic relationships were inferred using the maximum likelihood (ML) approach, implemented in IQ-TREE version 2.3.4 (Minh et al, Reference Minh, Schmidt, Chernomor, Schrempf, Woodhams, von Haeseler A and Lanfear2020). ML analyses were conducted with the options – m MFP – b 1000, and model selection based on the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) identified GTR + F + R4 as the best-fitting model. Bayesian phylogenetic inference was performed using MrBayes v3.2.7 (Ronquist et al, Reference Ronquist, Teslenko, van der Mark, Ayres, Darling, Höhna, Larget, Liu, Suchard and Huelsenbeck2012). Since the GTR + F + R4 model is not implemented in MrBayes, we selected the best model according to IQ-TREE BIC ranking, which is supported by MrBayes: GTR + F + I + G4. Two independent Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) runs were executed under this model, each with four chains and 10,000,000 generations. Chains were sampled every 100 generations, with a burn-in of 25%. Convergence was assessed by confirming that the average standard deviation of split frequencies dropped below 0.01 prior to the burn-in threshold and that all potential scale reduction factor (PSRF) values approached 1.0 at the end of the run.

Quantifying phylogenetic signal of host and environmental traits

For each 18S rRNA sequence included in the phylogenetic tree, we retrieved information on three traits: (1) the host’s environment at the time of collection (marine, freshwater, brackish or terrestrial); (2) the geographical origin of the sample (Africa, America, Asia, Europe or Marine); and (3) the taxonomy of fish host, categorized as Chondrichthyes, Tetrapodomorpha, Elopomorpha, Osteoglossomorpha, Otomorpha, Protacanthopterygii, Paracanthopterygii and Percomorpha. This information was primarily obtained from GenBank flat files, which often include the Latin name of the host and the geographic origin of the sample. When such data were not available in the flat file, we consulted the original publications linked to the sequences to extract the missing information. Sequences for which we were unable to confirm key metadata were excluded from the analysis. For example, we could not determine the host of the sequence MN925668_Myxidium_sp, either from the flat file or from any associated publication, and thus this sequence was not included to compute the δ-statistic relating to the host taxonomy. In cases where the environment was not explicitly stated in the publication or flat file, we inferred this information from the ecological characteristics of the host species as described in FishBase (Froese and Pauly, Reference Froese and Pauly2025), or from contextual clues such as the sampling site. For instance, inland water bodies were assumed to represent freshwater environments. As an example, the sequence MH497019_Myxidium_pseudocuneiforme was collected from a common carp in Chongqing, China (Chen et al, Reference Chen, Zhang, Whipps, Yang and Zhao2021). Although FishBase lists common carp as inhabiting freshwater, brackish, or benthopelagic environments, we coded the environment as freshwater due to the inland location of Chongqing. Similar logic was applied consistently across all records. We emphasize that the recorded traits reflect the host species, geographic origin and environment at the specific time and location of collection. We acknowledge that myxozoan species may infect multiple host species and that host species may occur across various environments (e.g., catadromous species) or geographic regions (e.g., invasive fish). However, for consistency, we only considered the characteristics of the sample at the time and place of collection.

For each of these three traits, the different states were coded as discrete numerical values (see Supplementary Table S1) and used to compute the δ-statistic (Ribeiro et al, Reference Ribeiro, Borges, Rocha and Antunes2023), which quantifies the degree of phylogenetic signal between a categorical trait and a phylogenetic tree. Sequences lacking information for a given trait (e.g., sequences originating from annelids with unknown host classification) were pruned from the phylogenetic tree and excluded from the corresponding trait analysis. All computations were performed using the Python scripts available at https://github.com/diogo-s-ribeiro/delta-statistic (Ribeiro et al, Reference Ribeiro, Borges, Rocha and Antunes2023). Marginal probabilities were computed using PastML (Ishikawa et al, Reference Ishikawa, Zhukova, Iwasaki and Gascuel2019), employing the marginal posterior probabilities approximation (MPPA) prediction method under the F81 maximum likelihood model. The δ-statistic was calculated using the Linear Shannon Entropy measure, and default parameters (lambda0 = 0.1, se = 0.5, sim = 100,000, thin = 10, burn = 100). To estimate the P-value associated with the δ-statistic, a reference distribution was generated by randomizing the trait vector 1,000 times, following the recommendations provided at https://github.com/mrborges23/delta_statistic (Borges et al, Reference Borges, Machado, Gomes, Rocha and Antunes2019). A δ-statistic value was computed for each randomized dataset, and the P-value was derived by comparing the observed δ-statistic value to this empirical distribution.

Results

Taxonomic summary

Myxidiidae Thélohan, 1892

Myxidium Bütschli, 1882

Myxidium grauri n. sp.

Plasmodia: Small coelozoic plasmodia (about 0.4 mm in diameter), visible with naked eye, rounded, creamish white, freely floating in the bile.

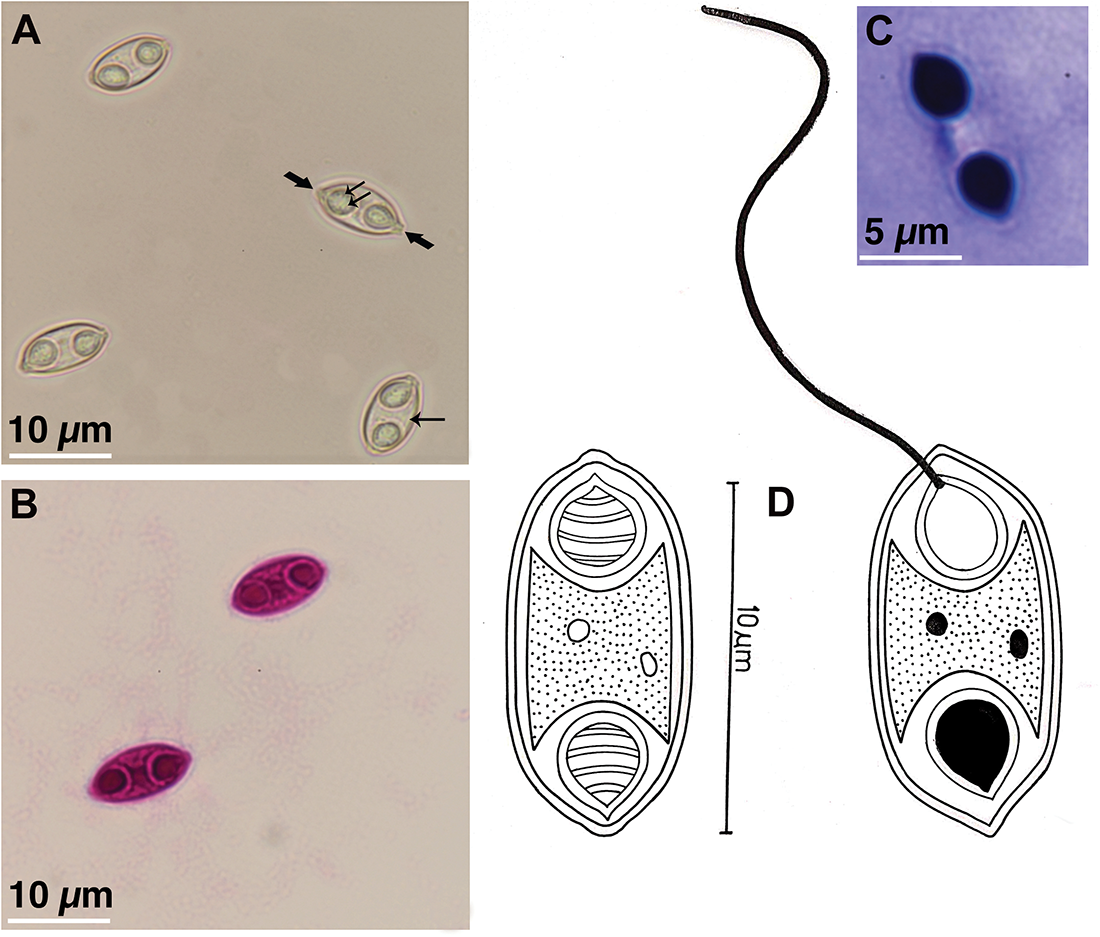

Myxospore: The following description is based on the observation of myxospores isolated from a single plasmodium. Mature myxospores fusiform in valvular view and cylindrobiconical in sutural view with bluntly pointed ends displaying squared capsular foramina (or extrusion pores). They measure 14.23 ± 0.61 (12.58–15.79) µm in length and 5.74 ± 0.49 (4.46–7.1) µm in width. The LS/WS ratio (length of myxospore/width of myxospore) is 2.47. Polar capsules pyriform to ovoidal, equal in size and present at the ends of the myxospore measuring 5.13 ± 0.28 (4.16–5.81) µm in length and 3.09 ± 0.50 (2.10–3.88) µm in width. Polar tubules form 5 coils within the capsules and measure 25–30 µm when extruded. The sutural line is straight, and the shell valves are striated with 6–8 longitudinal striations converging towards the myxospore ends (Figure 1).

Figure 1. (A) fresh myxospore of Myxidium grauri n. sp. isolated from the gallbladder of Carasobarbus canis. Note the conspicuous coiled polar tubule within a polar capsule (double arrows); bluntly pointed ends displaying squared capsular foramina (or extrusion pores) (thick arrow) and longitudinal striations on the myxospore (single arrow); (bB) myxospores stained with Ziehl-Neelsen; (cC) line drawing of the myxospore; (dD) Giemsa stained myxospore with extruded polar tubule.

Type host: Carasobarbus canis (Valenciennes, 1842), vern. Jordan himri, Family: Cyprinidae

Type locality: Sea of Galilee (31˚ 49ˊ N, 35˚ 38ˊ E) off Israel

Material: Two slides with stained myxospores (SMNHTAU-AP-62-63) have been deposited in the parasite collection of the Steinhardt Museum of Natural History, Tel-Aviv University, Israel

Infection site: Gallbladder

Prevalence of infection (%): 42.2% (19/45)

Clinical signals: Whitish plasmodia floating inside the gallbladder

Representative DNA sequences: GenBank accession number OP174300 (2,032 bp)

ZooBank registration code: urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:3060DCBB-ED5D-44F3-880F-E60856DCD31B

Etymology: The specific epithet ‘grauri’ honours Professor Dan Graur (University of Houston & Tel-Aviv University), for his many contributions to the field of molecular evolution (from scientific debates to graphical cover designs) and in appreciation of his support to D.H. through the years.

Remark: No co-infection with other myxozoan species was detected in the C. canis gallbladders examined, although a few Myxobolus spores were observed in a small number of gallbladders that were not infected by M. grauri n. sp.

Myxidium sharmai n. sp.

Plasmodia: Small coelozoic plasmodia (about 0.4 mm), visible with naked eye, rounded, creamish white, freely floating in the bile.

Myxospore: The following description is based on the observation of myxospores isolated from a single plasmodium. Mature myxospores fusiform in valvular view and cylindrobiconical in sutural view with bluntly pointed ends displaying squared capsular foramina (or extrusion pores). They measure 10.57 ± 0.36 (10.04–11.48) µm in length and 5.43 ± 0.31 (4.36–6.1) µm in width. The LS/WS ratio (length of myxospore/width of myxospore) is 1.94. Polar capsules pyriform to ovoidal, equal in size and present at the ends of the myxospore measuring 3.32 ± 0.28 (2.54–3.94) µm in length and 2.51 ± 0.32 (2.0–3.13) µm in width. Polar tubule forms 4 coils within the capsules and measures 7–10 µm when extruded. The sutural line is straight, and the shell valves are striated with 5–6 longitudinal striations converging towards the myxospore ends (Figure 2).

Figure 2. (A) fresh myxospores of Myxidium sharmai n. sp. isolated from the gallbladder of Luciobarbus longiceps. Note the conspicuous coiled polar tubule within a polar capsule (double arrows); bluntly pointed ends displaying squared capsular foramina (or extrusion pores) (thick arrow) and longitudinal striations on the myxospore (single arrow); (bB) myxospores stained with Ziehl-Neelsen; (cC) Giemsa stained myxospore; (dD) line drawing of the myxospore with extruded polar tubule.

Type host: Luciobarbus longiceps (Valenciennes, 1842), vern. Jordan barbel, Family: Cyprinidae

Type locality: Sea of Galilee (31˚ 49ˊ N, 35˚ 38ˊ E) off Israel

Material: Two slides with stained myxospores (SMNHTAU-AP-64-65) have been deposited in the parasite collection of the Steinhardt Museum of Natural History, Tel Aviv University, Israel

Infection site: Gallbladder

Prevalence of infection (%): 25% (05/20)

Clinical signals: Whitish plasmodia floating inside the gallbladder

Representative DNA sequences: GenBank accession number OP174299 (2,028 bp)

ZooBank registration code: urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:3060DCBB-ED5D-44F3-880F-E60856DCD31B

Etymology: The specific epithet ‘sharmai’ has been given in honour of Hari Prakash Sharma, an Indian educator, environmentalist and social worker from Mohali district of Punjab (India), in appreciation for his teaching to A.G during primary schooling.

Remark: During the study, we frequently observed co-infections in the gallbladders of L. longiceps involving M. sharmai n. sp. and an undescribed Chloromyxum species. Unfortunately, despite repeated efforts, we were unable to obtain sequence data for this species, likely due to its consistently lower abundance relative to M. sharmai n. sp. No other myxozoan species was observed in the L. longiceps gallbladders examined.

Morphological comparison of Myxidium grauri n. sp. and Myxidium sharmai n. sp.

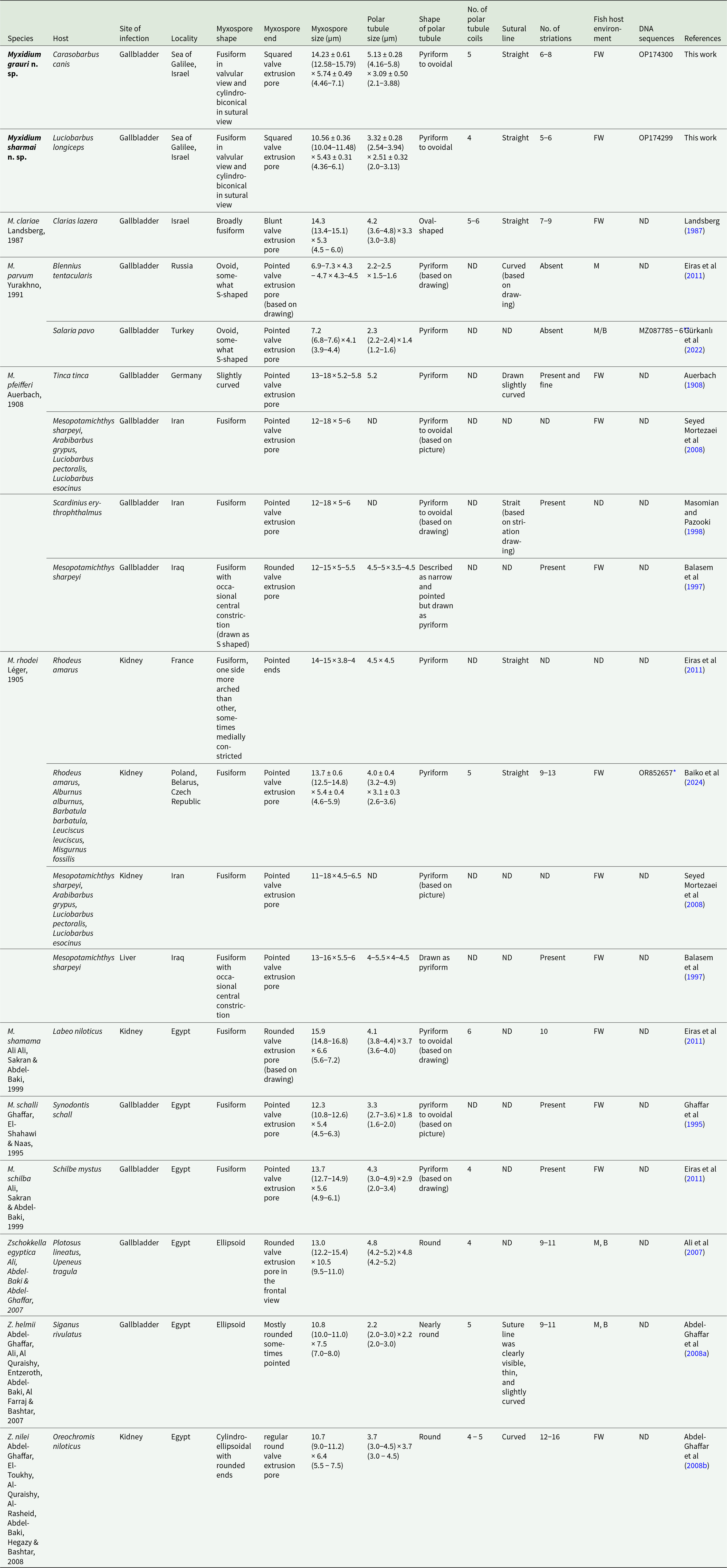

The myxospore morphology of the two newly described species is characteristic of the genus Myxidium. These species are distinguished from other Myxidium and Zschokkella species previously reported from freshwater and brackish environments in the Levant by their host specificity, as they represent the first Myxidium species described from fish endemic to the Jordan River basin. Additionally, they differ from other myxozoan parasites infecting hosts in this geographical region in few morphological traits, including myxospore shape and size, polar capsule dimensions, number of tubule coils, sutural line morphology, presence or absence of striations, and infection site (Table 2).

Table 2. Comparative description of Myxidium grauri n. sp. and Myxidium sharmai n. sp. with Myxidium and Zschokkella species infecting fish host from freshwater and brackish present in the Levant (measurements in micrometre)

FW, freshwater; M, marine; B, brackish; ND, no data.

* This sequence was published after we completed the phylogenetic analysis.

** Belong to biliary tract II clade, a lineage distinct from the one represented in the phylogenetic tree reconstructed in this study.

‘Present’ indicates that striations were mentioned or observed in the corresponding publication; however, the exact number of striations was not specified.

Like most Myxidium parasites, M. grauri n. sp. and M. sharmai n. sp. infects the gallbladder of their hosts. This distinguishes them from M. rhodei, M. shamama and Z. nilei, which parasitize the kidney of their respective hosts. The fusiform, cylindrobiconical shape of the myxospores further differentiates M. grauri n. sp. and M. sharmai n. sp. from M. parvum (ovoid, S-shaped), Z. egyptica and Z. helmii (ellipsoid) and Z. nilei (cylindro-ellipsoidal with rounded ends). Additionally, the straight myxospore shape of M. grauri n. sp. and M. sharmai n. sp. contrasts with the original description of M. pfeifferi, which reports that its myxospores are often slightly arched in shape (Auerbach, Reference Auerbach1908).

The small myxospore size of M. sharmai n. sp. (10.56 ± 0.36 × 5.43 ± 0.31 µm) contrasts with the larger myxospores of all other species listed in Table 2, all of which exceed 12 µm on average, except for M. parvum, Z. helmii, and Z. nilei, which have distinctly different myxospore shapes (see above), and M. schalli. While the myxospore dimensions of M. sharmai n. sp. overlap with those of M. schalli (12.3 [10.8–12.6] × 5.4 [4.5–6.3] µm), their polar capsules differ in shape. Specifically, the polar capsules of M. sharmai n. sp. are wider (3.32 ± 0.28 [2.54–3.94] × 2.51 ± 0.32 [2.0–3.13] µm) than those of M. schalli (3.3 [2.7–3.6] × 1.8 [1.6–2.0] µm). Additionally, M. schalli infects Synodontis schall, a siluriform fish host, whereas M. sharmai n. sp. infects a cypriniform host. Notably, S. schall is not found in the Jordan River basin.

The myxospores of M. grauri n. sp. (14.23 ± 0.61 [12.58–15.79] × 5.74 ± 0.49 [4.46–7.1] µm) are larger than those of M. sharmai n. sp. and M. schalli but overlap in size with two other Myxidium species that also exhibit a fusiform myxospore shape and infect the gallbladder: M. clariae (14.3 [13.4–15.1] × 5.3 [4.5–6.0] µm), which has thinner myxospores on average, and M. schilba (13.7 [12.7–14.9] × 5.6 [4.9–6.1] µm), which has shorter myxospores on average. The polar capsule dimensions of these two species also overlap with those of M. grauri n. sp. M. grauri n. sp. can be distinguished from M. schilba by having a greater number of polar tubule coils (5 vs. 4). However, this count is within the range observed in M. clariae (5–6 coils). The main distinguishing feature between M. grauri n. sp. and M. clariae is the larger average polar capsule size in M. grauri n. sp. (5.13 ± 0.28 [4.16–5.8] × 3.09 ± 0.50 [2.1–3.88]) compared to (4.2 [3.6–4.8] × 3.3 [3.0–3.8]) in M. clariae, although their size ranges overlap. Furthermore, M. grauri n. sp. was found in a cypriniform host, whereas M. schilba and M. clariae infect siluriform fish. Considering these morphological and host differences, M. grauri n. sp. is proposed as a new species rather than a synonym of M. clariae.

In addition to morphological distinctions mentioned above, molecular data further support the separation of M. grauri n. sp. and M. sharmai n. sp. as distinct sister species. Unfortunately, none of the other species listed in Table 2 have been sequenced, preventing direct molecular comparisons.

Phylogenetic analysis

The sequencing of the 18S rRNA gene from the myxospores of M. grauri n. sp. and M. sharmai n. sp. resulted in sequences of 2,032 bp and 2,028 bp with a guanine-cytosine (GC) content of 46.5%, and 46%, respectively. The sequences presented 95.3% of identity with each other.

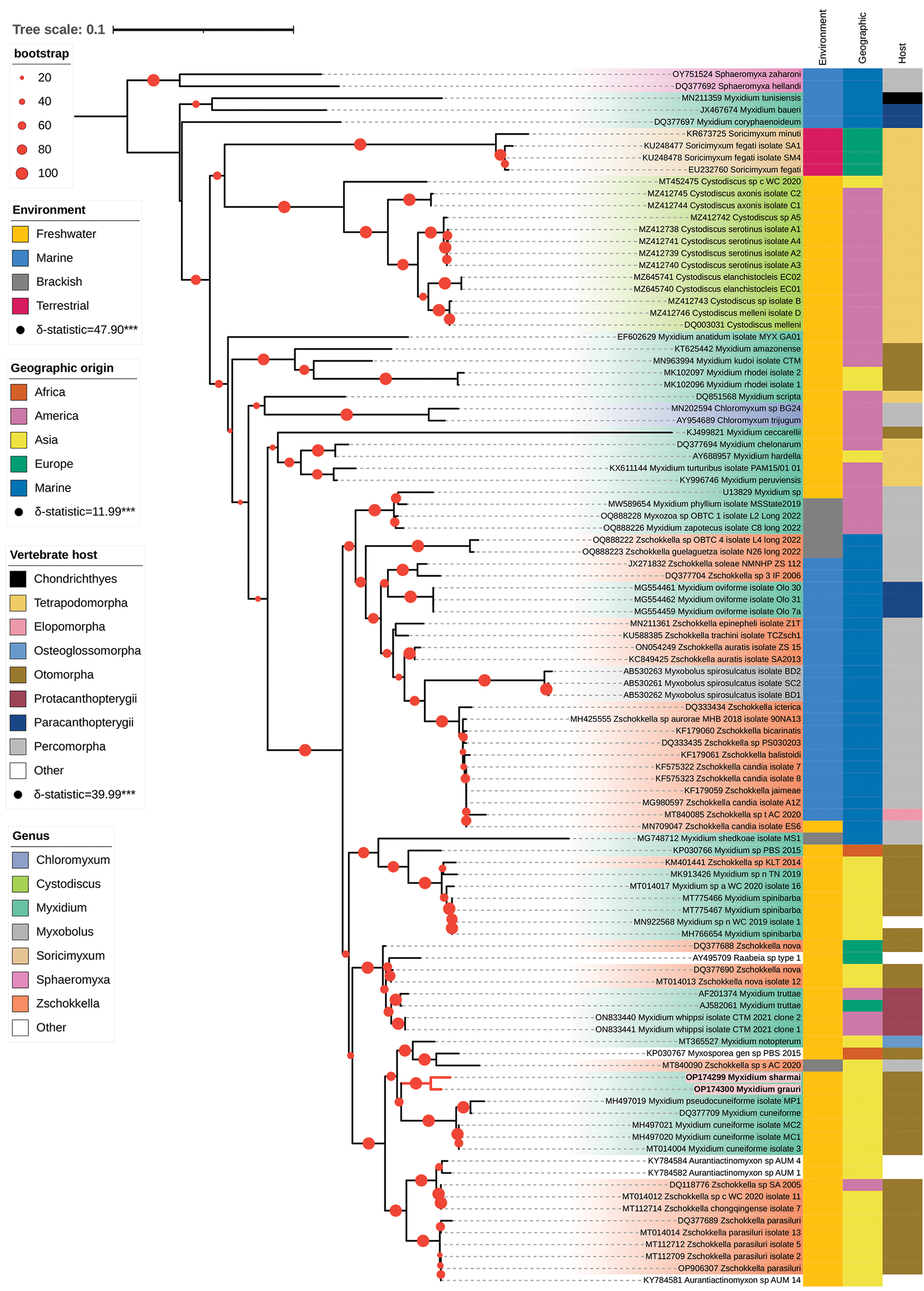

The reconstructed maximum likelihood (Figure 3) and Bayesian (Supplementary Figure S1a) phylogenetic trees include species from seven main genera, with Sphaeromyxa used as the outgroup to root the trees. Both methods recovered largely congruent phylogenetic relationships, with only two minor discrepancies. First, in the likelihood tree, Myxidium ceccarellii (KJ499821) forms a monophyletic group together with Myxidium chelonarum (DQ377694), M. hardella (AY688957), M. turturibus (KX611144) and M. peruviensis (KY996746) (bootstrap percentage, BP = 36). In contrast, in the Bayesian tree, Myxidium ceccarellii and the other four Myxidium species form a paraphyletic group (posterior probability, PP = 0.54). Second, Zschokkella sp. KLT2014 (KM401441) clusters with Myxidium sp. PBS2015 (KP030766) in the likelihood tree (BP = 52), whereas in the Bayesian tree, it appears as sister to the Myxidium spinibarba clade (PP = 57). Notably, both of these differences are associated with low node support values in the maximum likelihood tree and Bayesian tree (see Supplementary Figure S1b for bootstrap support values in the ML tree).

Figure 3. Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree of the biliary tract clade IV (102 taxa; IQ-TREE). Coloured strips, adjacent to each species name, indicated from left to right the environment, geographic origin, and host clade associated with each parasite sequence. These traits exhibit significant phylogenetic signal, as indicated by high δ-statistic values. Parasite genera are differentiated by distinct background shading, and Israeli sequences are specifically highlighted with a red background and red branches. Bootstrap support values are indicated by red circles, with circle size proportional to the level of support.

A strong phylogenetic signal was detected for the environmental origin of the sequences (δ-statistic = 47.90; P-value < 0.001). The outgroup sequences along with the three species located at the base of the tree (Myxidium tunisiensis MN211359, Myxidium baueri JX467674 and Myxidium coryphaenoideum DQ377697) originate from marine environments. This suggests that the ancestor of the biliary tract clade IV was marine. In contrast, the majority of the remaining species were sampled from freshwater environments. The phylogenetic distribution of these freshwater sequences thus indicates an early marine-to-freshwater transition. Additionally, as expected, the terrestrial samples from shrew hosts, appear to have evolved from a freshwater ancestor (Figure 3). A distinct, well-supported clade (BP = 100, PP = 1.0), composed of species sampled from marine environments, is nested within the broader freshwater taxa. This clade includes, among others, sequences from the species Myxidium oviforme, Zschokkella auratis, Myxobolus spirosulcatus and Zschokkella candia. Interestingly, species from brackish environments are placed as sister groups to this marine clade (e.g., Myxidium zapotecus OQ888226, Myxidium phyllium MW589654, Zschokkella guelaguetza OQ888223), suggesting that the freshwater-to-marine transition may have occurred via a brackish environment intermediate.

A strong phylogenetic signal was also detected for geographic origin (δ-statistic = 12.90; P-value < 0.001). Only two freshwater samples originated from Africa, and both are nested within samples that originated from Asia. This likely reflects limited funding for sequencing rather than a genuine lack of biodiversity in this region. No samples from Oceania were present in the dataset. Most freshwater samples originate from Asia and the Americas, with the samples from the Sea of Galilee nested among samples from Asiatic origin.

The myxozoan sequences considered in our analysis were obtained from a wide range of hosts spanning multiple vertebrate clades (Figure 3), highlighting extensive host diversity and suggesting numerous host-switching events throughout evolution. Nevertheless, host taxonomy retains a strong phylogenetic signal (δ-statistic = 49.99; P-value < 0.001), indicating non-independence between host taxonomy and parasite evolutionary histories. The phylogenetic signal is particularly evident when comparing host distributions between marine and freshwater environments. Of the 40 freshwater Actinopterygii samples, 31 (77.5%) are from Otomorpha hosts (Siluriformes, Cypriniformes and Characiformes). In contrast, 20 of the 27 marine Actinopterygii samples (74.1%) are from Percomorpha hosts. These observations reflect the typical ecological distributions of Otomorpha and Percomorpha, which dominate freshwater and marine environments, respectively (Carrete Vega and Wiens, Reference Carrete Vega and Wiens2012). Interestingly, parasites infecting brackish-water hosts are associated with Percomorpha species, suggesting that the transition from brackish to marine environments likely occurred within Percomorpha hosts. In total, 23 sequences (19.5% of the dataset) are from tetrapod hosts, including frogs, shrews, turtles and birds. Notably, tetrapod hosts have been reported from only a few myxozoan clades (Holzer et al, Reference Holzer, Bartošová-Sojková, Born-Torrijos, Lövy, Hartigan and Fiala2018). The turtle-infecting Myxidium species are polyphyletic, in agreement with previous studies (Kristmundsson and Freeman, Reference Kristmundsson and Freeman2013; Espinoza et al, Reference Espinoza, Mertins, Gama, Fernandes Patta and Mathews2017). Moreover, the two clades of turtle-infecting Myxidium are distinct from those infecting frogs (Cystodicus clade) and shrews (Soricimyxum clade), suggesting that shifts to terrestrial hosts have occurred multiple times independently during the diversification of this myxozoan lineage.

The Israeli species are nested among freshwater species, which primarily includes parasites of Otomorpha hosts. They represent the first sequenced Myxidium parasites of barbs (Cypriniformes) and form a maximally supported clade (BP = 100, PP = 100). This clade is sister to a group comprising Myxidium cuneiforme (MH497020, MH497021, MT014004) and M. pseudocuneiforme (MH497019, DQ377709), parasites of Carassius auratus and Cyprinus carpio from China and Japan (Chen et al, Reference Chen, Zhang, Whipps, Yang and Zhao2021) (BP = 66 and PP = 83). Together, these two groups form a sister clade to Myxidium notopterum (MT365527) from Malaysia and India, along with two undescribed species (MT840090_Zschokkella_sp_s_AC_2020 and KP030767_Myxosporea_gen_sp_PBS_2015) (BP = 69, PP = 98).

Discussion

The present study describes two novel Myxidium species (family Myxidiidae) infecting the gallbladder of two barb species, C. canis and L. longiceps, respectively, from the Sea of Galilee. Carasobarbus canis and L. longiceps are cyprinid fish that were formerly classified within the genus Barbus, a group that historically included around 800 species distributed across Eurasia and Africa. However, extensive phylogenetic studies over the past 25 years have significantly revised the classification of this group, revealing that many species previously assigned to Barbus are not closely related, demonstrating that the genus, as once defined, is polyphyletic (Durand et al, Reference Durand, Tsigenopoulos, Unlü and Berrebi2002; Tsigenopoulos et al, Reference Tsigenopoulos, Ráb, Naran and Berrebi2002, Reference Tsigenopoulos, Kasapidis and Berrebi2010; Geiger et al., Reference Geiger, Herder, Monaghan, Almada, Barbieri, Bariche, Berrebi, Bohlen, Casal-Lopez, Delmastro and Denys2014; Yang et al, Reference Yang, Sado, Vincent Hirt, Pasco-Viel, Arunachalam, Li, Wang, Freyhof, Saitoh, Simons, Miya, He and Mayden2015). These studies have shown that Carasobarbus and Luciobarbus belong to distinct cyprinid tribes: Torini and Barbini, respectively.

The genus Carasobarbus (Cyprinidae) includes species native to major freshwater systems in northwestern Africa (e.g., northern Morocco) and southwestern Asia (including the Levant, Mesopotamia, southern Iran, and the Arabian Peninsula) (Borkenhagen and Krupp, Reference Borkenhagen and Krupp2013). In contrast, the genus Luciobarbus (Cyprinidae) includes species native to freshwater systems in southern Europe (e.g., the Iberian Peninsula and the Balkans), North Africa and western to Central Asia, with populations also present in the Near East and in rivers flowing into the Aral and Caspian Seas (Froese and Pauly, Reference Froese and Pauly2025). Both Carasobarbus canis and Luciobarbus longiceps are endemic to the Jordan River basin, occurring in Israel, Jordan and Syria. Populations of both species are in decline, and they are currently listed as Near Threatened and Endangered, respectively (Borkenhagen and Krupp, Reference Borkenhagen and Krupp2013; Freyhof, Reference Freyhof2014a, Reference Freyhofb; Froese and Pauly, Reference Froese and Pauly2025).

Although fish are a heavily exploited resource in the Sea of Galilee (Gophen, Reference Gophen1986), their myxozoan parasites remain poorly studied. Only a few publications have described the myxozoans of this ecosystem, primarily focusing on economically important or cultured species. Landsberg (Reference Landsberg1985) reported myxozoan infections by Myxobolus sarigi, Myxobolus equatorialis, Myxobolus israelensis, Myxobolus agolus and Myxobolus galilaeus in cultured tilapias (hybrids of Oreochromis aureus × Oreochromis niloticus) and in the mango tilapia (Sarotherodon galilaeus), while Landsberg (Reference Landsberg1987) described five myxozoan species Henneguya laterocapsulata, Henneguya suprabranchiae, Sphaerospora inaequalis, Myxidium clariae and Myxobolus heterofilamentatus from the North African catfish (Clarias gariepinus). Lövy et al (Reference Lövy, Smirnov, Brekhman, Ofek and Lotan2018) described Myxobolus bejeranoi from cultured tilapia hybrids (Oreochromis niloticus × O. aureus). Finally, Gupta et al (Reference Gupta, Haddas-Sasson, Gayer and Huchon2022) recently documented two myxozoans Myxobolus pupkoi and Myxobolus exiguus from mullets (Chelon labrosus and Chelon ramada, respectively). However, to date, no studies have investigated myxozoan infections in barb species in the Sea of Galilee.

The high prevalence of myxozoan infection observed in this study, i.e. 42.2% for Myxidium grauri n. sp. and 25% for Myxidium sharmai n. sp., indicates that these parasites are not only well established but also relatively common within their respective host species. This level of infection in barbs also raises important questions about possible subclinical effects on fish health and emphasizes the need for ongoing parasitological monitoring in the region, particularly given the ecological and economic value of the lake’s fish fauna (Goren, Reference Goren1974; Gophen, Reference Gophen1986).

Among the 10 myxozoan species known from the Sea of Galilee, only one belongs to the genus Myxidium, and none belong to Zschokkella (Landsberg, Reference Landsberg1985, Reference Landsberg1987; Lövy et al, Reference Lövy, Smirnov, Brekhman, Ofek and Lotan2018; Gupta et al, Reference Gupta, Haddas-Sasson, Gayer and Huchon2022). Given that humans have exploited Carasobarbus and Luciobarbus species in this region since at least the Middle Pleistocene (Zohar et al, Reference Zohar, Alperson-Afil, Goren-Inbar, Prévost, Tütken, Sisma-Ventura, Hershkovitz and Najorka2022), it is remarkable that no previous parasitological surveys have targeted these hosts. Today, these barb species are of low commercial value in Israel, representing only about 7% of the total catch (Gophen, Reference Gophen1986), which may partly explain the lack of previous parasite reports.

Our findings suggest that the parasite diversity associated with the barb species from the Sea of Galilee may be underestimated. Notably, we frequently observed co-infections of L. longiceps gallbladders with an undescribed Chloromyxum species, representing a genus that has not yet been documented from freshwater fish in Israel. Interestingly, other Carasobarbus and Luciobarbus species (L. pectoralis, L. esocinus, C. luteus, L. xanthopterus) have been reported to have a gallbladder infected by Myxidium species in Iran and Iraq (Balasem et al, Reference Balasem, Mhaisen, Al-Khateeb and Asmar1997; Masomian and Pazooki, Reference Masomian and Pazooki1998; Seyed Mortezaei et al, Reference Seyed Mortezaei, Pazoki, Masomiay and Koor2008; Al-Jawda and Ali, Reference Al-Jawda and Ali2021). In these studies, the parasites were identified as M. pfeifferi and M. rhodei (Balasem et al, Reference Balasem, Mhaisen, Al-Khateeb and Asmar1997; Masomian and Pazooki, Reference Masomian and Pazooki1998; Adday et al, Reference Adday, Balasem, Mhaisen and AlKhateeb1999; Asmar et al, Reference Asmar, Balasem, Mhaisen, Al-Khateeb and Al-Jawda1999; Seyed Mortezaei et al, Reference Seyed Mortezaei, Pazoki, Masomiay and Koor2008; Al-Nasiri, Reference Al-Nasiri2013; Al-Jawda and Ali, Reference Al-Jawda and Ali2021). However, it is unlikely that these parasites correspond to true M. rhodei (Léger, Reference Léger1905; Eiras et al, Reference Eiras, Saraiva, Cruz, Santos and Fiala2011). Originally described from the European bitterling (Rhodeus amarus, Acheilognathidae), M. rhodei has been reported from more than 40 cyprinid species (e.g., Balasem et al, Reference Balasem, Mhaisen, Al-Khateeb and Asmar1997; Adday et al, Reference Adday, Balasem, Mhaisen and AlKhateeb1999; Asmar et al, Reference Asmar, Balasem, Mhaisen, Al-Khateeb and Al-Jawda1999; Seyed Mortezaei et al, Reference Seyed Mortezaei, Pazoki, Masomiay and Koor2008; Al-Nasiri, Reference Al-Nasiri2013; Al-Jawda and Ali, Reference Al-Jawda and Ali2021). Recent 18S rRNA sequence analyses, however, revealed that at least two cryptic species had been misassigned to M. rhodei (Baiko et al, Reference Baiko, Lisnerová, Bartošová-Sojková, Holzer, Blabolil, Schabuss and Fiala2024). Notably, M. rhodei infects the kidney, making it unlikely that the parasites found in the gallbladder of barb species from Iran and Iraq represent the same species. As a case in point, gallbladder parasites of Rutilus rutilus were found to form a distinct clade, represented in our phylogenetic tree by sequences MK102096 and MK102097, which were originally misidentified as M. rhodei (Baiko et al, Reference Baiko, Lisnerová, Bartošová-Sojková, Holzer, Blabolil, Schabuss and Fiala2024). These sequences are not closely related to those obtained in the present study. Similarly, the parasites from Iran and Iraq (Balasem et al, Reference Balasem, Mhaisen, Al-Khateeb and Asmar1997; Masomian and Pazooki, Reference Masomian and Pazooki1998; Seyed Mortezaei et al, Reference Seyed Mortezaei, Pazoki, Masomiay and Koor2008; Al-Jawda and Ali, Reference Al-Jawda and Ali2021) are unlikely to represent M. pfeifferi, a species originally described from the tench (Tinca tinca, Tincidae) (Auerbach, Reference Auerbach1908). To the best of our knowledge, M. pfeifferi has not been reported from tench in Iran, despite several parasite surveys (Pazooki and Masoumian, Reference Pazooki and Masoumian2012; Hajipour et al, Reference Hajipour, Valizadeh and Ketzis2023). In addition, M. pfeifferi myxospores were originally described as slightly curved (Auerbach, Reference Auerbach1908), a feature not mentioned in the descriptions of the barb parasites from Iran and Iraq (Balasem et al, Reference Balasem, Mhaisen, Al-Khateeb and Asmar1997; Masomian and Pazooki, Reference Masomian and Pazooki1998; Seyed Mortezaei et al, Reference Seyed Mortezaei, Pazoki, Masomiay and Koor2008).

Based on organ specificity (gallbladder infection), myxospore morphology and molecular data, we suggest that the Myxidium species previously reported from barb species in Iran and Iraq are unlikely to be true M. rhodei or M. pfeifferi. Instead, they may correspond to, or be closely related to, the new species described herein.

The myxospores of both M. grauri n. sp. and M. sharmai n. sp. exhibit morphological features typical of the genus Myxidium but not Zschokkella, as described by Lom and Dyková (Reference Lom, Dyková, Lom and Dyková1992) (Table 3), and this identification was further corroborated by molecular analyses, which placed the sequences of these parasites within the biliary tract IV clade (Holzer et al, Reference Holzer, Bartošová-Sojková, Born-Torrijos, Lövy, Hartigan and Fiala2018). Within this clade, members of the genera Myxidium and Zschokkella, which share closely related morphological characteristics, are phylogenetically intertwined (Canning et al, Reference Canning, Curry, Feist, Longshaw and Okamura2000; Lom and Dyková, Reference Lom and Dyková2006), complicating their taxonomic delineation. The taxonomy of Myxidium is further challenged by the presence of cryptic species; for instance, species formerly identified as M. rhodei have recently been reassigned to newly erected species, highlighting the extent of cryptic diversity within the group (Baiko et al, Reference Baiko, Lisnerová, Bartošová-Sojková, Holzer, Blabolil, Schabuss and Fiala2024).

Table 3. Morphological comparison between Myxidium and Zschokkella

Within this group of biliary-infecting parasites, a single major transition from freshwater to marine fish hosts is evident, consistent with previous studies (Holzer et al, Reference Holzer, Bartošová-Sojková, Born-Torrijos, Lövy, Hartigan and Fiala2018). This pattern reinforces the view that transitions between freshwater and marine environments are rare events in myxozoan evolution. Interestingly, our findings suggest that this transition may have originated in parasites infecting percomorph hosts inhabiting brackish environments.

Several studies have investigated which traits show non-random associations with myxozoan phylogeny. Among these, the site of infection has been most frequently highlighted (Andree et al, Reference Andree, Székely, Molnár, Gresoviac and Hedrick1999; Eszterbauer, Reference Eszterbauer2004; Shin et al, Reference Shin, Nguyen, Jeong, Jun, Kim, Han, Baeck and Park2014). In the case of the biliary tract IV lineage, the vast majority of species infect the bile ducts and/or the gallbladder. Only three species – Myxidium rhodei, M. scripta and M. hardela – infect the kidney, suggesting that renal infection has evolved independently multiple times. One species, M. spirospiculatus, has been reported to infect both the bile duct and the spinal cord (however, as mentioned below, the sequences of this species may be a contamination).

In addition to infection site, myxozoans have been suggested to coevolve with their vertebrate hosts. However, a relationship between myxozoan and host phylogeny has not been consistently tested using statistical methods (Andree et al, Reference Andree, Székely, Molnár, Gresoviac and Hedrick1999; Forro and Eszterbauer, Reference Forro and Eszterbauer2016; Holzer et al, Reference Holzer, Bartošová-Sojková, Born-Torrijos, Lövy, Hartigan and Fiala2018; Rocha et al, Reference Rocha, Azevedo, Oliveira, Â, Antunes, Rodrigues and Casal2019; Lisnerová et al, Reference Lisnerová, Fiala, Cantatore, Irigoitia, Timi, Pecková, Bartošová-Sojková, Sandoval, Luer, Morris and Holzer2020; Vieira et al, Reference Vieira, Osaki-Pereira, Abdallah, Oliveira, Duarte, da Silva Rj and de Azevedo2024). Cophylogenetic analyses using topology- and distance-based methods have been conducted by Holzer et al (Reference Holzer, Bartošová-Sojková, Born-Torrijos, Lövy, Hartigan and Fiala2018) and Lisnerová et al (Reference Lisnerová, Fiala, Cantatore, Irigoitia, Timi, Pecková, Bartošová-Sojková, Sandoval, Luer, Morris and Holzer2020). These studies revealed ancient co-speciation signals across major myxozoan clades. Notably, myxozoans infecting chondrichthyans as well as myxozoans infecting tetrapods are often branching near the base of their respective clades, in congruence with vertebrate phylogeny, where Chondrichthyes, Tetrapoda, and Actinopterygii represent distinct lineages. In the case of the biliary tract IV lineage, the branching of Myxidium tunisiensis, a parasite of chondrichthyans, close to the outgroup aligns with this broader pattern, as well as the position of the tetrapod infecting species. Holzer et al (Reference Holzer, Bartošová-Sojková, Born-Torrijos, Lövy, Hartigan and Fiala2018) also noted that the co-speciation signal becomes weaker at lower taxonomic levels, likely due to host switching. Nevertheless, other studies have identified lower-scale host associations in specific clades, such as a distinct clade of myxobolids infecting mugilid fishes (Rocha et al, Reference Rocha, Azevedo, Oliveira, Â, Antunes, Rodrigues and Casal2019; Vieira et al, Reference Vieira, Osaki-Pereira, Abdallah, Oliveira, Duarte, da Silva Rj and de Azevedo2024), or a correlation between elasmobranchs and their infecting chloromyxids (Lisnerová et al, Reference Lisnerová, Fiala, Cantatore, Irigoitia, Timi, Pecková, Bartošová-Sojková, Sandoval, Luer, Morris and Holzer2020). However, as noted by many authors, our knowledge of the Myxozoa diversity is still limited (e.g., Okamura et al, Reference Okamura, Hartigan and Naldoni2018). For this reason, we chose to test host association at higher taxonomic levels (e.g., fish orders or above) rather than at the species level, where statistical power would be limited in our case. To assess host associations, we encoded fish families as discrete characters and tested for phylogenetic signal. This approach is similar to the one used by Shin et al (Reference Shin, Nguyen, Jeong, Jun, Kim, Han, Baeck and Park2014) to detect a correlation between host specificity and myxobolid phylogeny. Although this method is relatively coarse, it still yielded strong evidence for non-independence between parasite and host phylogeny. However, this result is likely confounded by the dominance of Percomorpha and Otomorpha hosts in the marine and freshwater environment, respectively (Carrete Vega and Wiens, Reference Carrete Vega and Wiens2012). Future studies with more larger host sampling within each environment will be essential to validate the presence of phylogenetic patterns within these two clades.

Finally, we also examined whether parasite phylogeny is associated with geographic origin. The presence of geographic signal in myxozoan phylogeny has already been noted in Lisnerová et al (Reference Lisnerová, Fiala, Cantatore, Irigoitia, Timi, Pecková, Bartošová-Sojková, Sandoval, Luer, Morris and Holzer2020). However, in our case, it is likely that this signal may be driven by non-random sampling, as most biliary tract IV sequences used in our analyses originate from China and the United States. Another limitation of our approach is that we did not subdivide the marine environment into distinct biogeographical regions, due to the limited number of marine myxozoan species included in our analyses. Further studies are needed to rigorously test the role of geography, using broader and more balanced sampling (see Okamura et al, Reference Okamura, Hartigan and Naldoni2018). Such investigations may ultimately help reveal whether observed biogeographic patterns reflect historical dispersal routes, host distribution, or both.

Members of the biliary tract IV clade are principally from the genera Zschokkella, Myxidium, Cystodiscus and Soricimyxum, all belonging to the family Myxidiidae and characterized by elongated myxospores with two polar capsules, one at each myxospore end (Lom and Dyková, Reference Lom and Dyková2006; Prunescu et al, Reference Prunescu, Prunescu, Pucek and Lom2007; Hartigan et al, Reference Hartigan, Fiala, Dyková, Rose, Phalen and Šlapeta2012). However, within this clade, we observed two notable exceptions: sequences of Myxobolus spirosulcatus (among the marine clade) (Yokoyama et al, Reference Yokoyama, Yanagida, Freeman, Katagiri, Hosokawa, Endo, Hirai and Takagi2010) and sequences of Chloromyxum trijugum (Hallett et al, Reference Hallett, Atkinson, Holt, Banner and Bartholomew2006) and Chloromyxum sp. MN202594 (Lovy et al, Reference Lovy, Friend and Lewis2019). These two genera belong to different families and are characterized by different myxospore morphologies: spherical myxospores with four apical polar capsules in Chloromyxum and ovoid myxospores with two apical polar capsules in Myxobolus (Lom and Dyková, Reference Lom and Dyková2006; Eiras et al, Reference Eiras, Lu, Gibson, Fiala, Saraiva, Cruz and Santos2012, Reference Eiras, Cruz, Saraiva and Adriano2021). Since these are the only representatives of their respective genera within this clade and the sequences were generated in single studies without replication by other researchers, we cannot exclude the possibility that these sequences represent contamination by co-infecting Myxidium species present in the gallbladder at the time of sequencing. This is a plausible explanation, as we encountered similar issues when attempting to amplify the Chloromyxum parasite found in L. longiceps.

Overall, this study provides compelling morphological and molecular evidence supporting the recognition of M. grauri n. sp. and M. sharmai n. sp. as distinct Myxidium species. Their discovery expands our understanding of myxozoan diversity in the Jordan River basin and emphasizes the need for further studies integrating molecular, morphological and ecological data to refine the taxonomy and evolutionary history of Myxidium species.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182025100723.

Data availability

Additional data that support the findings of this study are available as follows: All the uncropped images of Myxidium grauri n. sp. and M. sharmai n. sp. are available in the Figshare repository (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.20424795.v2). The 18S rRNA sequences of M. grauri n. sp. and M. sharmai n. sp. are available in GenBank under accession numbers OP174300 and OP174299, respectively. The COI sequences of C. canis and L. longiceps are deposited in GenBank with accession numbers PP506515 and PP506519, respectively. The raw phylogenetic tree and alignment files are available in the Figshare repository (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29091998.v2).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Captain Menachem Lev (Kibbutz Ein Gev fishing vessel) for providing the fish samples; Prof Noa Shenkar (Tel-Aviv University) for sharing her microscope apparatus and providing technical help; Kfir Gayer (Steinhardt Natural History Museum) for fish identification; Dr Shevy Rothman (Steinhardt Natural History Museum) for her help with the sample submission; and Prof Tal Pupko (Tel Aviv University) for his help with the computation of the δ-statistic and his valuable comments on the manuscript.

Author contributions

A.G. and D.H. conceived and designed the study; A.G. and M.H.-S conducted the field survey; A.G. performed the dissections, the taxonomic descriptions as well as the sequencing work with the help of M.H.-S. D.H. performed the phylogenetic analysis. A.G. and D.H. wrote the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Financial support

This research was funded by Israel Science Foundation (grant number 652/20 to D.H.).

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical standards

The sampling of commercial fish was done with the approval of the Israeli Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security.

Nomenclatural acts

This work, and the nomenclatural acts it contains, has been registered in ZooBank. The ZooBank Life Science Identifier (LSID) for this publication is: urn:lsid:zoobank.org:3060DCBB-ED5D-44F3-880F-E60856DCD31B.