Introduction

The northern hookworm, Uncinaria stenocephala, is the main hookworm species infecting dogs in temperate regions, while Ancylostoma species are more common in tropical and subtropical areas (Gibbs, Reference Gibbs1961; Beveridge, Reference Beveridge2002; Xhaxhiu et al., Reference Xhaxhiu, Kusi, Rapti, Kondi, Postoli, Rinaldi, Dimitrova, Visser, Knaus and Rehbein2011). Among these, Ancylostoma caninum is the most widespread hookworm in dogs from warmer climates and is known to cause anaemia. In contrast, U. stenocephala infection usually leads to protein-losing enteropathy rather than anaemia (Walker and Jacobs, Reference Walker and Jacobs1985).

Hookworm infections are typically treated with benzimidazole-class anthelmintics (Geary et al., Reference Geary, Drake, Gilleard, Chelladurai, Jimenez Castro, Kaplan, Marsh, Reinemeyer and Verocai2025). However, resistance to these drugs in A. caninum is now a major concern, with evidence suggesting it may be widespread (Geary et al., Reference Geary, Drake, Gilleard, Chelladurai, Jimenez Castro, Kaplan, Marsh, Reinemeyer and Verocai2025). Notably, benzimidazole resistance in hookworms may not be limited to A. caninum (Leutenegger et al., Reference Leutenegger, Lozoya, Tereski, Savard, Ogeer and Lallier2023, Reference Leutenegger, Evason, Willcox, Rochani, Richmond, Meeks, Lozoya, Tereski, Loo, Mitchell, Andrews and Savard2024; Venkatesan et al., Reference Venkatesan, Jimenez Castro, Morosetti, Horvath, Chen, Redman, Dunn, Collins, Fraser, Andersen, Kaplan and Gilleard2023; Abdullah et al., Reference Abdullah, Stocker, Kang, Scott, Hayward, Jaensch, Ward, Jones, Kotze and Šlapeta2025). Recent studies have identified the F167Y mutation in the isotype-1 β-tubulin gene of U. stenocephala from Australia, indicating possible resistance in this species too (Abdullah et al., Reference Abdullah, Stocker, Kang, Scott, Hayward, Jaensch, Ward, Jones, Kotze and Šlapeta2025; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Li, Suwandy, Mitrea, Hayward, Jaensch, Francis and Šlapeta2025).

Besides domestic dogs, the European red fox (Vulpes vulpes) is a common host of U. stenocephala in both Europe and Australia (Coman, Reference Coman1973; Ryan, Reference Ryan1976; Saeed et al., Reference Saeed, Maddox-Hyttel, Monrad and Kapel2006; Reperant et al., Reference Reperant, Hegglin, Fischer, Kohler, Weber and Deplazes2007; Bružinskaitė-Schmidhalter et al., Reference Bružinskaitė-Schmidhalter, Šarkūnas, Malakauskas, Mathis, Torgerson and Deplazes2012; Dybing et al., Reference Dybing, Fleming and Adams2013). The role of fox-derived U. stenocephala in dog transmission cycles remains unclear. Three studies have explored this relationship. Two of these studies found, using short molecular markers, that U. stenocephala from dogs and foxes are genetically indistinguishable (Górski et al., Reference Górski, Długosz, Bartosik, Bąska, Łojek, Zygner, Karabowicz and Wiśniewski2023; Stocker and Šlapeta, Reference Stocker and Šlapeta2025). However, an earlier experimental study by Rep and Bos (Reference Rep and Bos1979) suggested red foxes may play a limited role in dog infections, as foxes infected with dog-derived U. stenocephala produced only low egg burdens compared to dogs.

To better understand the relationship between U. stenocephala populations in dogs and foxes, sequencing the mitochondrial genome (mtDNA or mitogenome) is a useful approach. The mitogenome is often the most accessible genome in hookworms, because each hookworm cell contains many mitochondria with multiple mitogenomes compared to singe nuclear genome. Although several hookworm species have had their mitogenomes characterized (Hu et al., Reference Hu, Chilton and Gasser2002; Jex et al., Reference Jex, Waeschenbach, Hu, van Wyk, Beveridge, Littlewood and Gasser2009; Gao et al., Reference Gao, Zhao, Liu, Zhang, Zhang, Wang, Chang, Wang and Zhu2014; Shi et al., Reference Shi, Wang, Abdullahi, Fu, Yang, Yu, Pan, Yan, Hang, Zhang and Li2018; Xie et al., Reference Xie, Xu, Zheng, Li, Liu, Wang, Zhou, Zuo, Gu and Yang2019; Tuli et al., Reference Tuli, Li, Li, Zhai, Wu, Huang, Feng, Chen and Yuan2022), a complete mtDNA sequence for U. stenocephala is still unavailable. The mitochondrial cox1 gene and the nuclear internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region of the rRNA gene unit are commonly used for molecular barcoding of nematodes (Mejías-Alpízar et al., Reference Mejías-Alpízar, Porras-Silesky, Rodríguez, Quesada, Alfaro-Segura, Robleto-Quesada, Gutiérrez and Rojas2024). While mitochondrial cox1 and nuclear ITS sequences from fox-derived U. stenocephala have been compared to those from dogs (Górski et al., Reference Górski, Długosz, Bartosik, Bąska, Łojek, Zygner, Karabowicz and Wiśniewski2023; Stocker and Šlapeta, Reference Stocker and Šlapeta2025), these studies have not examined the full mitochondrial genome.

Sampling adult U. stenocephala from dogs is challenging. However, red foxes frequently carry this parasite, making them a practical source (Stocker and Šlapeta, Reference Stocker and Šlapeta2025). To overcome the difficulty of obtaining adult worms, a genome skimming approach can be applied to faecal-derived material. Genome skimming involves shallow whole-genome sequencing of complex samples, such as faeces with potentially multiple parasites being present, to identify these parasites, their mitochondrial genomes are assembled and explored for their evolutionary relationships (Papaiakovou et al., Reference Papaiakovou, Fraija-Fernandez, James, Briscoe, Hall, Jenkins, Dunn, Levecke, Mekonnen, Cools, Doyle, Cantacessi and Littlewood2023).

In this study, we aimed to compare dog- and fox-derived U. stenocephala at the molecular level to assess their genetic relatedness. We characterized the complete mitochondrial genome using whole-genome sequencing and applied genome skimming to hookworm stages from dog faeces to expand sampling. We examined both intraspecific and interspecific genetic diversity of the mitogenomes. With access to complete mitogenomes, we investigated the monophyly of the genus Uncinaria. Our findings provide baseline insights into the identity of U. stenocephala and their conspecificity across red foxes and domestic dogs.

Material and methods

Sample isolation and sequencing

Whole-genome sequencing data were obtained from two individual U. stenocephala worms (TSF_1.1 and TSF_1.2), collected from a red fox culled in September 2024 in Mardi, New South Wales, Australia (33.2990° S, 151.4084° E) (Stocker and Šlapeta, Reference Stocker and Šlapeta2025). Paired-end sequencing reads (FastQ format) were retrieved from GenBank SRA under accession numbers SRR34168471 and SRR34168472 for TSF_1.1 and TSF_1.2, respectively.

Additional DNA samples were obtained from two concentrated hookworm egg samples containing U. stenocephala (TS66 from Canberra, Australia; TS78 from Whanganui, New Zealand), and two cultured third-stage larvae (L3) of A. caninum (TS87 and TS88 from Queensland, Australia), previously reported by Abdullah et al. (Reference Abdullah, Stocker, Kang, Scott, Hayward, Jaensch, Ward, Jones, Kotze and Šlapeta2025). All samples successfully amplified in three PCR assays targeting nuclear ITS2, BZ167 and BZ200 regions, with each assay yielding over 3020 sequencing reads. The U. stenocephala samples (TS66 and TS78) did not carry canonical benzimidazole resistance SNPs, while both A. caninum samples (TS87 and TS88) showed a high frequency of the F167Y resistance-associated SNP (Abdullah et al., Reference Abdullah, Stocker, Kang, Scott, Hayward, Jaensch, Ward, Jones, Kotze and Šlapeta2025).

Genomic DNA from the faecal egg isolates (TS66 and TS78) and cultured L3 larvae (TS87 and TS88) was submitted to Novogene (Hong Kong) for whole-genome sequencing. Sequencing depth was 3 Gb for TS66 and TS88, and 8 Gb for TS78 and TS87. Sequencing was performed using the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform with 150 bp paired-end chemistry.

Assembly and analysis of Uncinaria stenocephala Mitogenomes

Raw FastQ files were assessed using FastQC (http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/) and trimmed for low-quality reads and Illumina adapter sequences using Trimmomatic (Bolger et al., Reference Bolger, Lohse and Usadel2014). Mitogenomes of U. stenocephala (TSF_1.1 and TSF_1.2) and A. caninum (TS87) were assembled using GetOrganelle (Jin et al., Reference Jin, Yu, Yang, Song, dePamphilis, Yi and Li2020). Manual annotation was performed by aligning the newly assembled U. stenocephala mitogenomes to the reference A. caninum mitogenome (NC_012309). Circular genome maps were visualized using Proksee (Grant et al., Reference Grant, Enns, Marinier, Mandal, Herman, Chen, Graham, Van Domselaar and Stothard2023).

The new mitogenomes were aligned with publicly available hookworm mitogenomes across 12 protein-coding genes. Alignments and phylogenetic analyses were conducted in MEGA12 (Kumar et al., Reference Kumar, Stecher, Suleski, Sanderford, Sharma and Tamura2024).

Amino acid sequences of the 12 protein-coding genes were translated using the invertebrate mitochondrial genetic code. The alignment was curated using Gblocks v0.91b (Talavera and Castresana, Reference Talavera and Castresana2007) with default parameters, which retained 3376 of 3777 alignment positions (>99%) across 25 complete hookworm mitochondrial genomes. The mitogenome of Strongylus vulgaris was used as the outgroup. The curated alignment was imported into MEGA12 for model selection (Kumar et al., Reference Kumar, Stecher, Suleski, Sanderford, Sharma and Tamura2024). The best-fit amino acid substitution model was determined to be the Adachi-Hasegawa mitochondrial model (mtREV, Adachi and Hasegawa, Reference Adachi and Hasegawa1996) with empirical amino acid frequencies (+F), a discrete Gamma distribution with five rate categories to model rate heterogeneity among sites (+G), and a proportion of invariant sites (+I), resulting in the mtREV + F + G + I model. Phylogenetic trees were constructed using the Maximum Likelihood method implemented in MEGA12. Node support was assessed using adaptive bootstrap resampling (Kumar et al., Reference Kumar, Stecher, Suleski, Sanderford, Sharma and Tamura2024), with the number of replicates determined automatically by the software with 5% threshold. To assess the robustness of the observed tree topology, particularly the paraphyly of Uncinaria, we reconstructed the alignment after excluding the newly assembled U. stenocephala mitogenomes. This second alignment, comprising 20 hookworm mitogenomes, was processed using the same Gblocks parameters, retaining 3374 of 3777 residues (>99%). Phylogenetic inference was repeated as described above.

Pairwise nucleotide genetic distances (Kimura 2-parameter, K2P) were calculated in MEGA12 for all sequences. Maximum intraspecific and minimum interspecific distances were extracted and visualized in a scatterplot following the approach of Hebert et al. (Reference Hebert, Stoeckle, Zemlak and Francis2004).

Mapping of reads to mtDNA, ITS and β-tubulin isotype-1 genes

Illumina reads were mapped to the reference mitogenomes of A. caninum (TS87) and U. stenocephala (TSF_1.1) using BWA-MEM for alignment and SAMtools for file handling (Makino et al., Reference Makino, Ebisuzaki, Himeno and Hayashizaki2024). Reads were also mapped to the nuclear ITS region of U. stenocephala (PV848420), β-tubulin isotype-1 gene of U. stenocephala (PV133906) and β-tubulin isotype-1 gene of A. caninum (DQ459314). Coverage and mapping statistics were calculated using the BBMap pileup.sh command (https://github.com/BioInfoTools/BBMap)

Results

Genome skimming reveals high conservation of Uncinaria stenocephala ITS sequences

To investigate the molecular identity of U. stenocephala from red foxes and domestic dogs, we used the nuclear ITS sequence from an adult worm isolated from a red fox (TSF_1.1; Sanger-derived sequence, PV848420; 818 bp) as a reference. This was compared to low-coverage genome skimming data from two dog faecal samples containing hookworm eggs previously identified as U. stenocephala (TS66 from Australia and TS78 from New Zealand) (Abdullah et al., Reference Abdullah, Stocker, Kang, Scott, Hayward, Jaensch, Ward, Jones, Kotze and Šlapeta2025). After quality filtering, the nuclear ITS region showed average coverage of 14.5 × for TS66 and 1032.7 × for TS78, with 85 and 6344 mapped reads, respectively. TS66 had five detectable sequence variants, while TS78 had one. In comparison, the red fox-derived samples (TSF_1.1 and TSF_1.2) had much higher nuclear ITS coverage (9410.1 × and 3809.2 ×, respectively). No sequence variants were detected in TSF_1.1, and only one variant was found in TSF_1.2.

Characterization of the mitochondrial genome of Uncinaria stenocephala

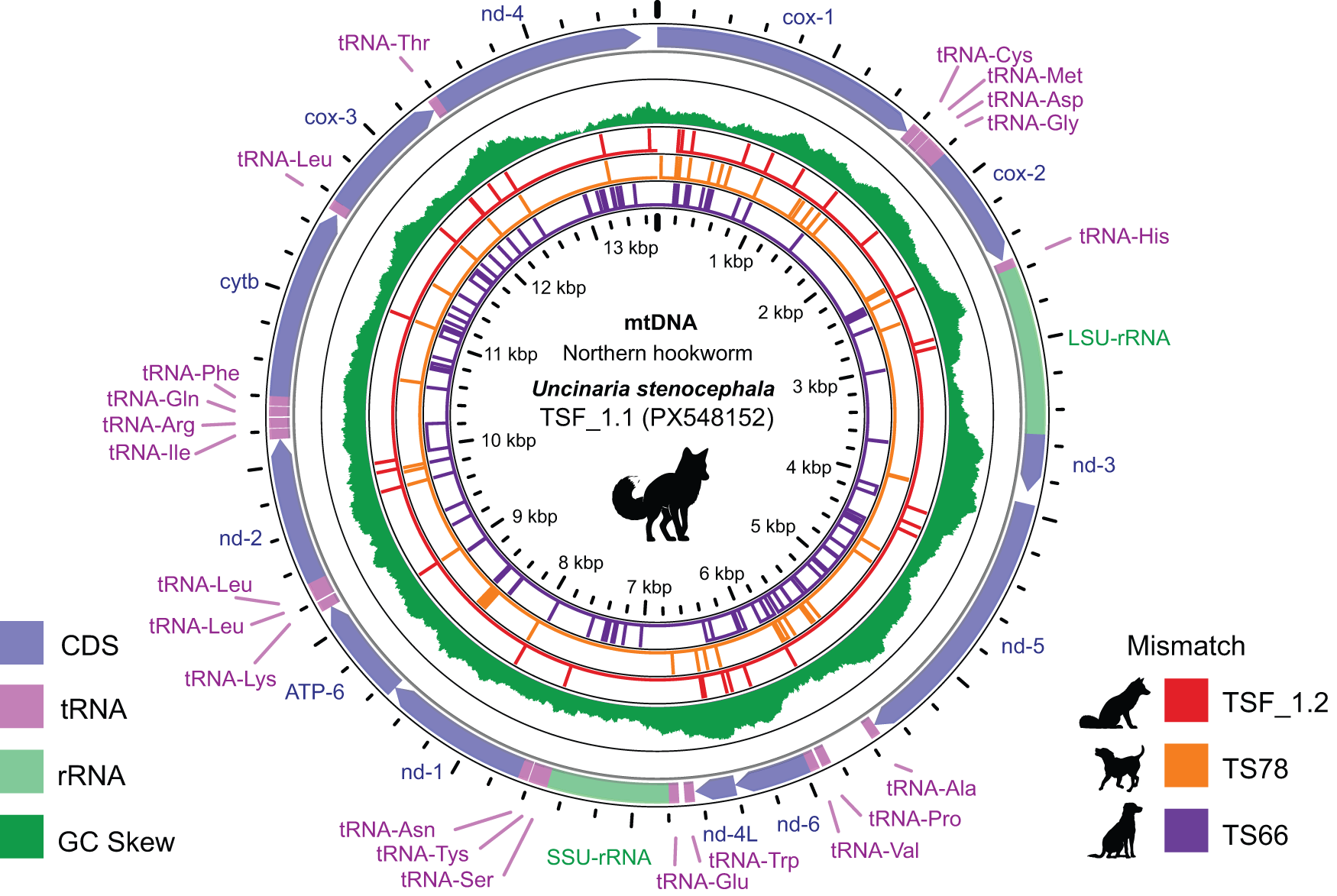

Given the high conservation of the nuclear ITS region, we assembled complete circular mitochondrial genomes (mitogenomes) from 2 morphologically verified U. stenocephala specimens (TSF_1.1 and TSF_1.2) (Stocker and Šlapeta, Reference Stocker and Šlapeta2025). Each mitogenome encoded 12 protein-coding genes, 22 tRNAs, and two rRNAs (Figure 1). Both genomes had a GC content of 22.7%, with thymine being the most frequent nucleotide (49%). Across the 12 coding genes, there were 29 nucleotide differences (99.7% identity). An additional 5 differences were found in non-coding regions. All genes except ND3 contained at least 1 variant, with mitochondrial cox1 being the most variable (seven SNPs).

Figure 1. Uncinaria stenocephala mitogenome. The circular DNA include 12 protein coding genes (CDS), 2 rRNA genes (rRNA) and 22 tRNA that are depicted on the outermost ring. The inner ring represents the GC content. Following three inner rings with vertical lines represent variable sites compared to the reference (TSF_1.1). The mitogenome of TSF_1.1 and TSF_1.2 were derived from two adult specimens of U. stenocephala from a red fox, TS66 and TS78 were derived from canine faecal samples with hookworm egg pools.

We then mapped low-coverage sequence data from dog-derived samples (TS66 and TS78) to the TSF_1.1 mitogenome to reconstruct dog-derived U. stenocephala mitogenomes and assess intraspecific diversity. Mapping of TS78 yielded nearly complete mitogenome coverage, with only 0.5% missing data (38/13 722 bp), all within a hypervariable intergenic region. TS78 had 31,433,349 reads and an average coverage depth of 26.3 × . TS66 had lower coverage (11 336 281 reads; 3.4 × depth), resulting in 88% mitogenome coverage and 12% missing data (1657/13 722 bp) (Table 1).

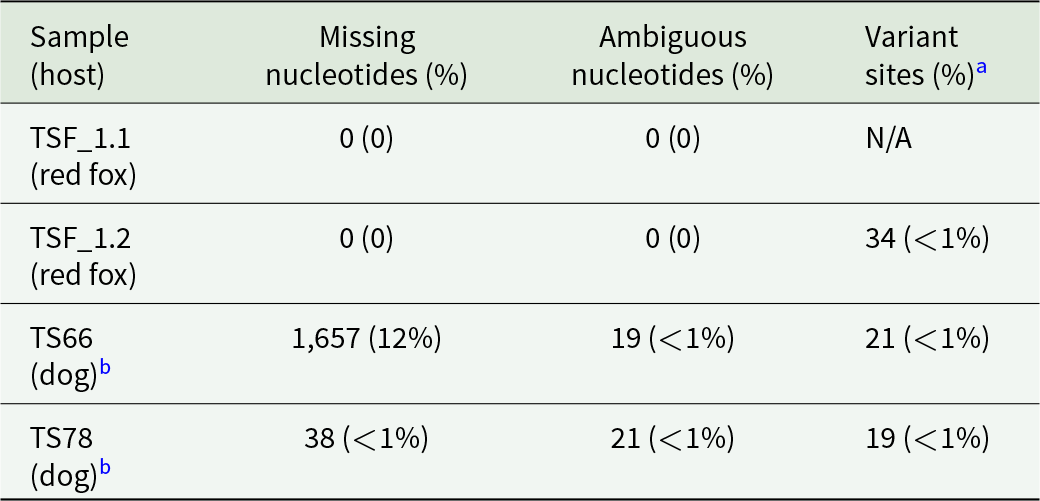

Table 1. Summary statistics for Uncinaria stenocephala mitogenomes

a Variant sites against a reference (TSF_1.1); N/A not applicable (reference sequence).

b Samples derived from faecal samples with hookworm eggs from an infected dog, representing a population of adults.

For comparison, we also mapped data from two A. caninum L3 samples (TS87 and TS88; Abdullah et al., Reference Abdullah, Stocker, Kang, Scott, Hayward, Jaensch, Ward, Jones, Kotze and Šlapeta2025). For A. caninum, complete mitogenomes were recovered from TS87 and TS88, with average depths of 442.3 × and 127.2 ×, respectively, from 33 653 543 and 12 515 934 reads.

Uncinaria stenocephala from dogs and red fox represent a single species based on mitogenome identity

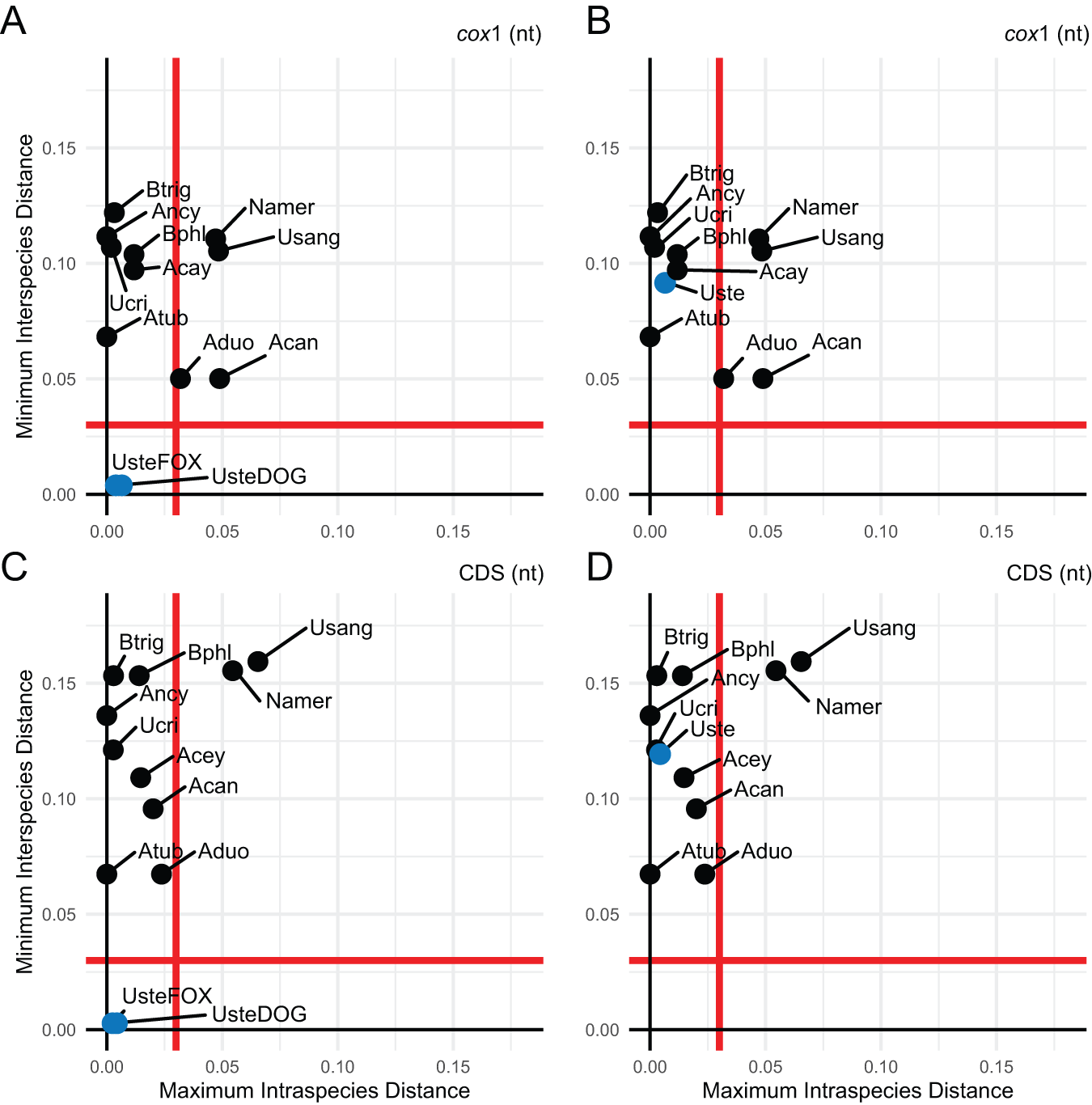

To assess host-associated divergence, we applied a DNA barcoding approach comparing minimum interspecies distances to maximum intraspecies distances (K2P), using a 3% threshold to define species boundaries (Hebert et al., Reference Hebert, Cywinska, Ball and deWaard2003, Reference Hebert, Stoeckle, Zemlak and Francis2004). We analysed four U. stenocephala mitogenomes (TS66, TS78, TSF_1.1, TSF_1.2) and two A. caninum mitogenomes, using both mitochondrial cox1 and concatenated coding sequences (CDS) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Relationship between intraspecific and interspecific genetic distances among Uncinaria stenocephala mitogenomes derived from red foxes and domestic dogs. Maximum intraspecific distances were compared to minimum interspecific congeneric differences using Kimura 2-parameter distances. (A) When analysing only the mitochondrial cox1 sequence, U. stenocephala sequences were divided into two putative host-adapted groups: red fox-derived (UsteFOX) and domestic dog-derived (UsteDOG). (B) In contrast, all U. stenocephala sequences were grouped together as a single species (Uste); mitochondrial cox1 sequence only. (C) When analysing the complete set of mitochondrial protein-coding sequences (CDS), U. stenocephala sequences were divided into two putative host-adapted groups: red fox-derived (UsteFOX) and domestic dog-derived (UsteDOG). (D) In contrast, all U. stenocephala sequences were grouped together as a single species (Uste) for the CDS-based analysis. Each graph includes a red line representing a 3% divergence threshold, dividing the plot into four quadrants that reflect species categories as defined by Hebert et al. (Reference Hebert, Stoeckle, Zemlak and Francis2004): the top left quadrant indicates species concordant with current taxonomy; the top right suggests probable composite species and candidates for taxonomic split; the bottom left represents species with recent divergence, hybridization, or synonymy; and the bottom right indicates probable specimen misidentification. Species abbreviations used in the figure include: Namer (Necator americanus), Usang (Uncinaria sanguinis), Ucir (Uncinaria criniformis), Acan (Ancylostoma caninum), Acey (Ancylostoma ceylanicum), Aduo (Ancylostoma duodenale), Atub (Ancylostoma tubaeforme), Ancy (Ancylostoma sp. HL-2021), Bphl (Bunostomum phlebotomum) and Btri (Bunostomum trigonocephalum).

When fox- and dog-derived U. stenocephala were treated as separate groups, they fell into the bottom-left quadrant of the scatterplot, indicating recent divergence or synonymy (Figure 2A, 2C). When treated as a single species, they shifted to the top-left quadrant, consistent with current taxonomy and so genetically indistinguishable based on mitochondrial cox1 and mitochondrial CDS (Figure 2B, 2D). In contrast, Necator americanus and U. sanguinis appeared in the top-right quadrant, suggesting they may be composite species. A. duodenale exceeded the 3% threshold in mitochondrial cox1, but not in CDS. A. caninum showed a similar pattern, with nearly 5% divergence in mitochondrial cox1, driven by the MN215971 mitogenome.

Uncinaria stenocephala from dogs and red fox are monophyletic

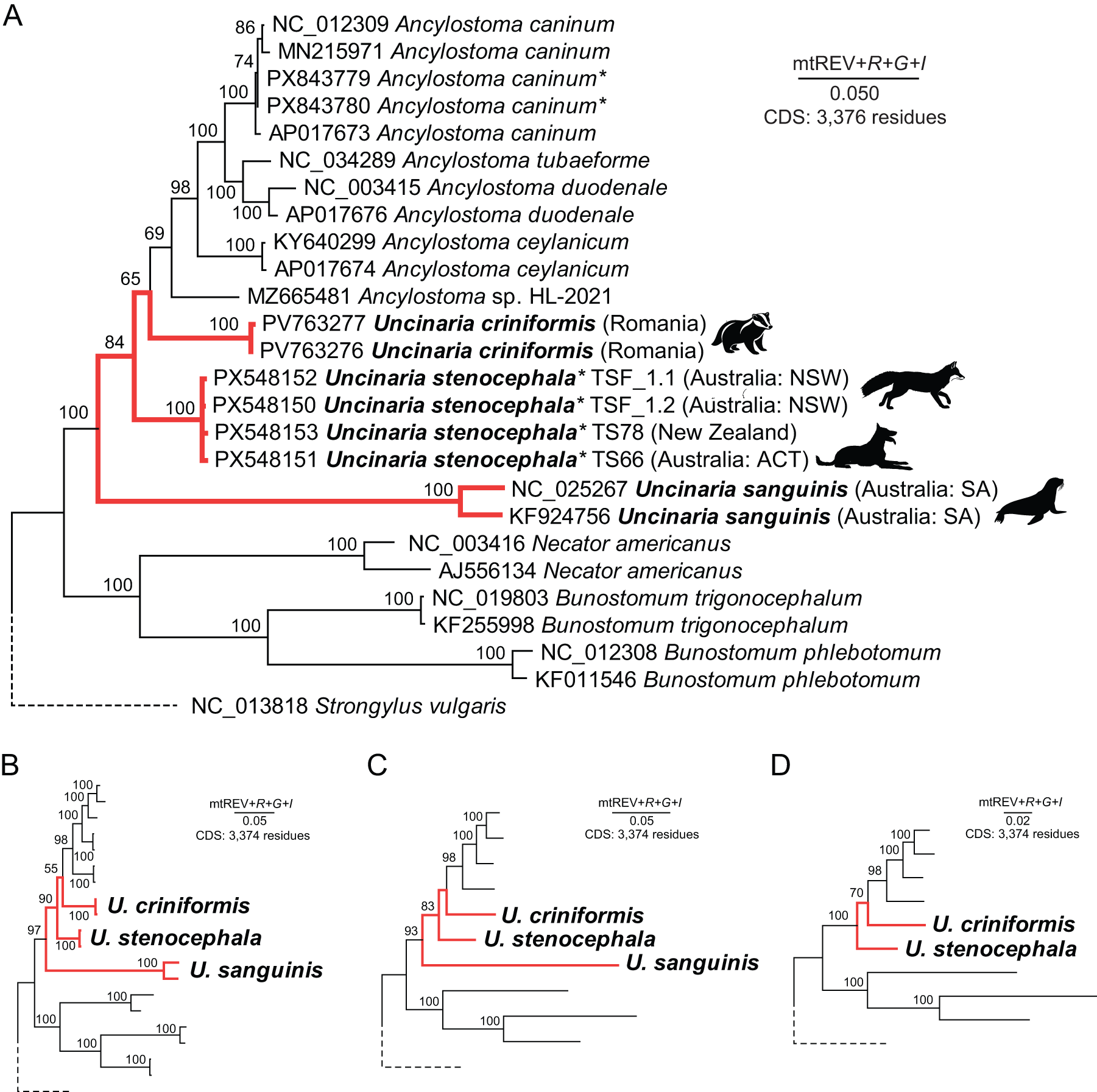

Using the newly assembled U. stenocephala mitochondrial genomes, we constructed a phylogenetic tree based on amino acid sequences from all 12 protein-coding genes. The maximum likelihood tree was inferred using the mtREV + F + G + I model. The genus Uncinaria appeared paraphyletic, with U. sanguinis (from pinnipeds) forming a distinct lineage separate from U. stenocephala, U. criniformis (from badgers) and all Ancylostoma spp. sequences (Figure 3). Bootstrap support for each individual Uncinaria species (U. stenocephala, U. criniformis, U. sanguinis) was absolute (100%) (Figure 3A). Bootstrap support for the nodes leading to Uncinaria species and the unnamed Ancylostoma sp. HL-2021 (MZ665481) was lower (65–84%) than in other parts of the tree (Figure 3A). This paraphyly persisted regardless of which sequences or species were excluded with variable bootstrap support for the nodes that led to paraphyletic Uncinaria clades. To further investigate, we removed Ancylostoma sp. HL-2021 and retained a maximum of two representatives per species. The tree was recalculated using the same model, yet Uncinaria species remained paraphyletic (Figure 3B). We then retained only a single representative per species (Figure 3C), and finally, we removed U. sanguinis entirely (Figure 3D). The paraphyly of U. stenocephala and U. criniformis and tree topology remained unchanged. The apparent paraphyly of Uncinaria remains unresolved, because the weak nodal support (<70% bootstrap) suggests that inclusion of additional Uncinaria spp. mitogenomes may improve tree resolution (Ilík et al., Reference Ilík, Schwarz, Nosková and Pafčo2024; Deak and Šlapeta, Reference Deak and Šlapeta2025).

Figure 3. Phylogenetic position of Uncinaria stenocephala based on mitochondrial protein-coding gene sequences. Maximum Likelihood trees were inferred using the Adachi and Hasegawa (Reference Adachi and Hasegawa1996) mitochondrial protein model with empirical amino acid frequencies (+F), gamma-distributed rate variation (+G), and a proportion of invariant sites (+I). Bootstrap support values (adaptively determined) are shown next to the branches. (A) Tree including all available hookworm mitogenomes, including newly assembled U. stenocephala (n = 4) and A. caninum (n = 2) sequences. Newly generated sequences are marked with an asterisk (*). Pictogram of host animal is next to Uncinaria spp. (badger, fox, dog, sea lion) (B) Tree excluding all newly generated mitogenomes from genome skimming. (C) Tree with only a single representative per hookworm species. (D) Tree with U. sanguinis removed and a single representative retained for each remaining species. In panels (B)–(D), only nodes corresponding to Uncinaria species are labelled.

Limited coverage of β-tubulin isotype-1 gene from genome skimming

Genome skimming of the U. stenocephala sample TS78 yielded only 22 reads mapping to the β-tubulin isotype-1 (tubb-1) gene, out of 62 866 698 total reads. These reads did not cover key codons (134, 167, 198, 200) associated with benzimidazole resistance. No reads mapped to tubb-1 in the TS66 sample.

In contrast, A. caninum L3 samples (TS87 and TS88) had better coverage of tubb-1 (7.7 × and 7.9 ×), but the gene was still only partially covered, with no reads spanning the benzimidazole resistance-associated codons.

Discussion

The mitogenomes of U. stenocephala recovered from red foxes were highly similar to those assembled from dog faecal egg isolates via genome skimming, with pairwise identity exceeding 99%. The genetic distance between fox- and dog-derived U. stenocephala was lower than that observed among A. caninum isolates, including three from Australian dogs. These findings support earlier studies based on nuclear ITS and partial mitochondrial cox1 sequences, which found no clear genetic distinction between U. stenocephala from dogs and foxes (Górski et al., Reference Górski, Długosz, Bartosik, Bąska, Łojek, Zygner, Karabowicz and Wiśniewski2023; Stocker and Šlapeta, Reference Stocker and Šlapeta2025). Genome skimming proved to be a practical and effective method for recovering complete or near-complete mitogenomes from faecal samples, especially when adult nematodes are inaccessible due to host status or sampling constraints (Papaiakovou et al., Reference Papaiakovou, Fraija-Fernandez, James, Briscoe, Hall, Jenkins, Dunn, Levecke, Mekonnen, Cools, Doyle, Cantacessi and Littlewood2023). Even shallow Illumina sequencing provided sufficient coverage for mitogenome reconstruction and the nuclear multicopy rDNA unit; however, it failed to yield adequate coverage for single-copy nuclear genes such as β-tubulin isotype-1, for which deep amplicon sequencing remains the more appropriate approach when considering benzimidazole resistance alleles (Venkatesan et al., Reference Venkatesan, Jimenez Castro, Morosetti, Horvath, Chen, Redman, Dunn, Collins, Fraser, Andersen, Kaplan and Gilleard2023; Abdullah et al., Reference Abdullah, Stocker, Kang, Scott, Hayward, Jaensch, Ward, Jones, Kotze and Šlapeta2025; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Li, Suwandy, Mitrea, Hayward, Jaensch, Francis and Šlapeta2025).

In contrast to the genetic evidence, earlier experimental work by Rep and Bos (Reference Rep and Bos1979) suggested that U. stenocephala strains in dogs and foxes may be host-adapted, with limited cross-infectivity. Their study showed that dog-derived U. stenocephala produced patent infections in foxes but with markedly reduced egg output, only 7% compared to dog-to-dog transmission, and less than 1% when fox-derived worms were used to infect dogs (Rep and Bos, Reference Rep and Bos1979). However, faecal egg counts are influenced by multiple factors, including worm burden, sex ratio and daily variation in egg shedding (Watkins and Harvey, Reference Watkins and Harvey1942). Additionally, the experimental infections used vastly different larval doses (25 000 vs 1000), and some dogs expelled larvae orally due to high infection pressure. The immune status of the hosts was not well characterized, and prior exposure may have influenced larval establishment (Ferguson et al., Reference Ferguson, Inclan-Rico, Lu, Bobardt, Hung, Gouil, Baker, Ritchie, Jex, Schwarz, Rossi, Nair, Dillman and Herbert2023). While our mitogenomic data support conspecificity of U. stenocephala from foxes and dogs, we cannot rule out phenotypic variation or host-specific adaptation. Further studies using variable nuclear markers across broader geographic regions are needed to clarify the contribution of fox-derived U. stenocephala to dog infections.

Molecular markers such as mitogenomes and nuclear ITS regions are increasingly recognized as complementary characteristics to morphology in hookworm systematics (Hu et al., Reference Hu, Chilton and Gasser2002; Jex et al., Reference Jex, Waeschenbach, Hu, van Wyk, Beveridge, Littlewood and Gasser2009; Gao et al., Reference Gao, Zhao, Liu, Zhang, Zhang, Wang, Chang, Wang and Zhu2014; Shi et al., Reference Shi, Wang, Abdullahi, Fu, Yang, Yu, Pan, Yan, Hang, Zhang and Li2018; Xie et al., Reference Xie, Xu, Zheng, Li, Liu, Wang, Zhou, Zuo, Gu and Yang2019). For example, the distinction between A. braziliense and A. ceylanicum was only resolved through DNA sequence analysis, particularly nuclear ITS region, which clarified their taxonomic status and ended longstanding speculation about their synonymy (Traub et al., Reference Traub, Inpankaew, Sutthikornchai, Sukthana and Thompson2008; Ngui et al., Reference Ngui, Mahdy, Chua, Traub and Lim2013; Traub, Reference Traub2013). Despite the public health relevance of A. braziliense, no complete mitogenome is currently available for this species. In fact, only a small number of morphologically described hookworm species have been characterized at the nucleotide level, and even fewer have complete mitogenomes (Ilík et al., Reference Ilík, Schwarz, Nosková and Pafčo2024).

In this study, we applied an arbitrary 3% threshold to assess nucleotide variability across available hookworm mitogenomes. When considering all protein-coding sequences, all but two species were consistent with current taxonomy. The exceptions were Necator americanus and Uncinaria sanguinis. In the case of U. sanguinis, a hookworm of pinnipeds, it is the only species within this group with published mitogenomes, despite the existence of numerous loosely host-associated Uncinaria species in pinnipeds worldwide, often characterized using partial mitochondrial cox1 and nuclear ITS sequences (Nadler et al., Reference Nadler, Lyons, Pagan, Hyman, Lewis, Beckmen, Bell, Castinel, Delong, Duignan, Farinpour, Huntington, Kuiken, Morgades, Naem, Norman, Parker, Ramos, Spraker and Beron-Vera2013; Haynes et al., Reference Haynes, Marcus, Higgins, Gongora, Gray and Šlapeta2014). This group likely harbours cryptic diversity, and genome skimming combined with mitogenomics directly from faecal samples collected antemortem could provide new insights into the taxonomy and evolutionary relationships within the genus. For N. americanus, mitogenomic variability was first noted by Hu et al. (Reference Hu, Chilton, YG and Gasser2003) when comparing samples from Togo and China, but no follow-up studies have explored whether these differences reflect biologically distinct populations. Interestingly, when we restricted our analysis to the mitochondrial cox1 gene alone, A. caninum, previously grouped with well-defined taxa, shifted into the quadrant suggesting potential cryptic species. This divergence was driven by the mitochondrial cox1 sequence from MN215971 (Xie et al., Reference Xie, Xu, Zheng, Li, Liu, Wang, Zhou, Zuo, Gu and Yang2019), derived from a stray dog in a shelter in Southwest China. Further sampling is needed to determine whether this divergence reflects local variation, a technical artefact, or genuine cryptic diversity, as the remainder of the mitogenome does not show similar divergence.

Conclusions

The characterization of the Uncinaria stenocephala mitogenome and its clear genetic distinction from the badger hookworm U. criniformis resolves longstanding speculation that these species may be synonymous (Ransom, Reference Ransom1924; Deak and Šlapeta, Reference Deak and Šlapeta2025). Although morphologically similar, the genetic distance between their mitogenomes was greater than previously assumed, challenging historical interpretations based solely on morphology (Looss, Reference Looss1905; Cameron, Reference Cameron1924; Ransom, Reference Ransom1924; Baylis, Reference Baylis1933; Wolfgang, Reference Wolfgang1956).

This study contributes to resolving hookworm taxonomy and highlights the utility of mitogenomics in clarifying species boundaries. However, the genus Uncinaria remains polyphyletic. Further mitogenomic characterization is needed across additional Uncinaria species and related genera, including Agriostomum, Arthrocephalus, Arthrosoma, Galoncus, Globocephalus, Hypodontus, Placoconus and Tetragomphius (Ilík et al., Reference Ilík, Schwarz, Nosková and Pafčo2024; Deak and Šlapeta, Reference Deak and Šlapeta2025). Expanding genomic datasets across these taxa will be essential for resolving phylogenetic relationships and refining the taxonomy of hookworms and related nematodes.

Data availability

The raw and intermediate data for all samples are available at LabArchives (https://dx.doi.org/10.25833/j9wf-9s30). Raw FastQ sequence data were deposited at SRA NCBI BioProject: PRJNA1347473 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA1347473). Mitogenome sequence data were deposited in GenBank under the following accession numbers: PX548150-PX548153 and PX843779-PX843780.

Author contribution

TS and JŠ designed the study. SA and IS collected the material. TS and JŠ performed the analyses. TS and JŠ wrote the article.

Financial support

The work was funded by the Betty & Keith Cook Canine Research Fund (The University of Sydney).

Competing interests

The authors declare there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

Not applicable for fox derived material as it was collected from culled animals that are pest animal in Australia, carcases were donated to the University of Sydney (Australia). The use of faecal residual clinical samples from dogs was in accordance with the University of Sydney (Australia) Animal Ethics Committee Protocol 2024/2508. Dog faecal samples for larval cultures were obtained in accordance with the University of Queensland (Australia) Animal Ethics Committee Protocol 2021/AE001169 and SVS/111/20.