Introduction

Different life situations and factors create varying poverty risks, and no single mechanism explains how transitions into or out of poverty occur. Although previous research has provided myriad evidence on the differences and similarities in how European welfare states tackle poverty, it is fair to assume that the poverty alleviation measures of the welfare state have varying impacts on individual poverty risk. Traditional poverty alleviation measures have focused on income compensation for labour market failures (job loss, unemployment) and personal events influencing livelihood (sickness, death, old age), providing short-term poverty alleviation. More recently, welfare states have adopted elements of the social investment paradigm (Hemerijck and Ronchi, Reference Hemerijck, Ronchi, Béland, Leibfried, Morgan, Obinger and Pierson2021), which emphasises capacitation, preventing social risks, promoting skills and employment, and increasing well-being; this approach has a longer-term positive influence on one’s poverty risk than traditional reactive welfare state provision (Hemerijck, Reference Hemerijck2013, Reference Hemerijck2017).

This study analyses how policies influence individual poverty risk by looking at policies through their main function. Although welfare state literature often examines ‘old’ traditional compensatory welfare policies separate from ‘new’ social investment policies (Vaalavuo, Reference Vaalavuo2013; Taylor-Gooby et al., Reference Taylor-Gooby, Gumy and Otto2015; Van Vliet and Wang, Reference van Vliet and Wang2015; Plavgo and Hemerijck, Reference Plavgo and Hemerijck2021), this article uses the social investment framework to apply a policy complementary perspective to policy analysis on poverty. Specifically, the article draws upon the social investment (SI) policy function framework, where buffer policies provide sufficient safety nets and income compensation, flow policies support work-family balance and smoother labour market transitions, and stock policies promote lifelong human capital (Hemerijck, Reference Hemerijck2017; Hemerijck et al., Reference Hemerijck, Ronchi and Plavgo2023). Considering the criticism of minimum income protection schemes being possibly inadequate in safeguarding individuals from poverty (Cantillon et al., Reference Cantillon, Van Mechelen, Pintelon, Van den Heede, Cantillon and Vandenbroucke2014), it is important to examine the policy impacts from the complementary perspective. This article uses unemployment benefits, minimum wage, and housing allowance to analyse the buffer function, parental leave, child allowances, and childcare to study the flow function, and adult education, institutional training (ALMP), and the number of young adults exiting education early to examine the stock function.

Previous research consistently shows higher poverty risk among women, particularly single mothers, due to disadvantages in the labour market, including low-paid and precarious jobs, and bearing child-rearing costs alone, and among young adults who experience multiple risky life course transitions such as leaving home, education, partnership formation, and labour market entry (Jenkins and Schluter, Reference Jenkins and Schluter2003; Gardiner and Millar, Reference Gardiner and Millar2006; Vandecasteele, Reference Vandecasteele2011; Brady et al., Reference Brady, Finnigan and Hübgen2017; O’Reilly et al., Reference O’Reilly, Leschke, Ortlieb, Seeleib-Kaiser and Villa2019; Unt et al., Reference Unt, Gebel, Bertolini, Deliyanni-Kouimtzi and Hofäcker2021; Zagel et al., Reference Zagel, Hübgen and Nieuwenhuis2021). Social policy literature has mainly brought forth the positive role of family policies and social transfers, such as ECEC, child benefits, and social assistance, in mitigating the poverty risk of single mothers (Misra et al., Reference Misra, Budig and Moller2007; Boeckmann et al., Reference Boeckmann, Misra and Budig2015; Zagel and Van Lancker, Reference Zagel and Van Lancker2022), whereas ALMP is considered the main policy tool for combating youth poverty with varying returns to employment and education (Caliendo et al., Reference Caliendo, Künn and Schmidl2011; European Commission, 2023). This article analyses the impact of all three policy functions against the poverty risk across age groups and family types, to provide a comprehensive analysis with policy complementarity approach on how various policies simultaneously influence poverty among risk groups.

Germany presents an interesting case study to examine the impact of SI policy functions on poverty risk due to major policy changes taken place since 2000. The German welfare state was built to support the male-breadwinner family model, but after the turn of the century, high unemployment, rapidly increasing poverty, and low fertility rates resulted in rapid and radical changes in many key welfare state institutions (Jenkins and Schluter, Reference Jenkins and Schluter2003; Seeleib-Kaiser, Reference Seeleib-Kaiser2016). Major reforms in childcare and work-life policies emphasised a stronger flow function by promoting female employment and shifted the focus towards dual-earner families. Despite these positive changes, the Hartz reforms shortened unemployment support, weakening the buffer function of the German welfare state. This was somewhat balanced by the increases in training and adult education to support the human capital stock (function). Nonetheless, the employment-focused provisions and heavily tax-oriented welfare system still benefit well-off families and have increased income inequality, exposing individuals and families who are in vulnerable situations, such as single parents and young adults, to a higher risk of poverty (Van Lancker and Ghysels, Reference Van Lancker and Ghysels2012; Zagel et al., Reference Zagel, Hübgen and Nieuwenhuis2021; Binder and Haupt, Reference Binder and Haupt2022).

This study examines how social investment policy functions impact the individual poverty risk in Germany from 2002 to 2018. By using longitudinal micro-level data from the German Socio-Economic Panel (G-SOEP) and various policy indicators, the study applies dualistic policy complementarities. First, policy functions are operationalised through packages containing multiple policy indicators categorised according to their intended function of stocks, flows, and buffers. Second, the interaction impacts across these policy function packages on poverty risk are studied. This operationalisation of the policy measures extends from previous literature, which has heavily relied on the social expenditure data and provides a new approach to studying policy impacts through their complementary functions. By examining the combined influence of policies, the article aims to better capture the institutional realities of different demographic groups, particularly focusing on differences by gender, age, and family status. This information sheds light on whether and how SI policy functions may influence societal inequalities based on demographics.

Poverty alleviation through the lens of SI policy functions

In recent decades, changes in demographics, new social risks, and changing societies have required many welfare states to implement elements of social investment alongside the traditional redistributive social protection systems; work-family reconciliation, skill formation, and activation (Van Kersbergen and Hemerijck, Reference Van Kersbergen and Hemerijck2012; Hemerijck, Reference Hemerijck2017; Hemerijck and Ronchi, Reference Hemerijck, Ronchi, Béland, Leibfried, Morgan, Obinger and Pierson2021). Hence, recent studies have used a distinction between the ‘old’ compensatory social protection and ‘new’ social investment policies to bring forth positive macro- and micro-level poverty returns to these policies (Maldonado and Niewenhuis, Reference Maldonado and Nieuwenhuis2015; Plavgo and Hemerijck, Reference Plavgo and Hemerijck2021), some being more cautious on the ability of SI supporting the most disadvantaged groups in the society (Cantillon, Reference Cantillon2011; Vandenbroucke and Vleminckx, Reference Vandenbroucke and Vleminckx2011; Van Vliet and Wang, Reference van Vliet and Wang2015). Considering the complex phenomenon of poverty, single policies or policy types alone are not able to alleviate poverty, but cash transfers, services, and skill enhancement may all be required simultaneously. Hence, this article extends from the dichotomous approach in SI literature and uses SI as a lens to analyse the policy complementarities across various policies on poverty risk.

This article employs the policy function framework of buffers, flows, and stocks from the social investment framework to analyse policy impacts with a policy complementary perspective (Hemerijck, Reference Hemerijck2013, Reference Hemerijck2017). This approach combines policies together based on their main function, allowing to analyse policy impacts through their conjoint effects. Policies that provide safety nets and income compensation for labour market failures or personal crises, aiming to maintain adequate household financial resources for a sufficient livelihood, represent the buffer function. Policies that smooth labour market transitions in employment and promote more gender equal labour market attainment through work-family reconciliation represent the flow function. Policies that foster human capital development from compulsory education to higher education and lifelong learning (LLL) represent the stock function. Each function is expected to have varying impacts on individual poverty risk based on demographic factors, such as family status, and life course stage of the individual (Hemerijck et al., Reference Hemerijck, Ronchi and Plavgo2023). Although all policies are equally available to both men and women, opportunities in the labour market, gender norms, care responsibilities, and other societal issues cause gender disadvantages and differences in experiencing poverty. Hence, the article focuses on the differences across age groups, family types, and gender in individual poverty risk.

The buffer function provides a safety net to compensate for income loss during labour market failures, such as unemployment, and social problems, such as falling ill. Such policies include, for example, social assistance, unemployment benefits, and housing allowance, all of which have a direct and imminent impact on individual poverty risk by sustaining resource-sufficient livelihoods. These have traditionally been the main welfare state tools to tackle poverty, and previous research has found that generous social security transfers can moderate the negative consequences of job loss and reduce individual poverty risk (Brady et al., Reference Brady, Fullerton and Cross2010; O’Campo et al., Reference O’Campo, Molnar, Ng, Renahy, Mitchell, Shankardass, John, Bambra and Muntaner2015). While many policies with a buffer function often have universal and targeted elements, monetary social benefits are found to have a particularly positive impact on single mothers’ poverty risk (Brady and Burroway, Reference Brady and Burroway2012; Zagel et al., Reference Zagel, Hübgen and Nieuwenhuis2021).

The flow function includes policies that support individuals during labour market and family transitions. For clarity, this article focuses on the policies that promote work-family balance. Early childhood education and care (ECEC) and parental leave with sufficient income replacement are key policies within the flow function. They emphasise mothers as both caregivers and earners and are associated with higher maternal employment and more working hours (Boeckmann et al., Reference Boeckmann, Misra and Budig2015), a reduction in precarious employment (Zoch and Hondralis, Reference Zoch and Hondralis2017) and diminished poverty risk (Misra et al., Reference Misra, Budig and Moller2007; Zagel and Van Lancker, Reference Zagel and Van Lancker2022). Family cash transfers, such as child allowances, compensate for the costs of child-rearing and alleviate the pressures on parents’ labour market returns, and have been found to reduce poverty, particularly among single mothers (Lohmann, Reference Lohmann2009; Maldonado and Niewenhuis, Reference Maldonado and Nieuwenhuis2015; Leventi et al., Reference Leventi, Sutherland and Tasseva2019) and low-income households (Van Lancker and Van Mechelen, Reference Van Lancker and Van Mechelen2015). Although the child benefit, as a cash transfer, could also be analysed within the buffer function, here its main function is considered to be promoting work-life balance over a long-time span enabling parents to maintain existing labour market situation without a need for improved returns, instead of buffering only the increased costs of child-rearing for a short period.

Policies with a stock function provide the means to create, maintain, update, and upgrade one’s skills and human capital. ALMP training programmes and adult education are central policies. ALMP training programmes are found to be promoting higher employment and educational participation among young adults (Caliendo et al., Reference Caliendo, Künn and Schmidl2011; Cefalo and Scandurra, Reference Cefalo and Scandurra2023), and increased employment for unemployed single mothers (Zabel, Reference Zabel2013). Adult education can increase one’s earnings (Stenberg, Reference Stenberg2010) and promote employment prospects of low-skilled youth (Knipparth and De Rick, Reference Knipprath and De Rick2014). These are vital in poverty alleviation as social protection or employment promotion alone might be insufficient to tackle the multidimensional issue of poverty and the needs of individuals in in-work poverty (Lohmann, Reference Lohmann2009; Cantillon et al., Reference Cantillon, Van Mechelen, Pintelon, Van den Heede, Cantillon and Vandenbroucke2014). Yet, research has provided scarce evidence of the impacts of the stock function on poverty.

The above section has presented SI policy functions separately, expressing how they may influence different groups and life dimensions, yet they can also impact individuals simultaneously, creating policy complementarities. Some scholars have found multiplicative mechanisms of policies; for example, Plavgo (Reference Plavgo2023) found that investments in education increased the effectiveness of ALMP on employment, and Hemerijck et al. (Reference Hemerijck, Burgoon, di Pietro and Vydra2016) demonstrated an employment-boosting influence of ECEC when the social security transfers were strong. On the other hand, policies can also substitute for an effect when another policy is weak. For example, Niewenhuis (Reference Nieuwenhuis2022) found that while ALMP investment was low, ECEC was able to promote female employment even more strongly than when ALMP investment was high. Although all these studies focus on employment outcomes, it can be assumed that the policy complementarities would also have an influence on poverty, considering its alleviation requires welfare states to adopt various mechanisms for different social risks and demographic groups. Therefore, this study uses a novel two-level approach to examine policy complementarities. First, various policy indicators are used to create packages that reflect the SI policy functions, enabling an analysis of multiple policies simultaneously. Second, the interaction analyses between the policy functions examine further complementary relations.

Based on the theoretical and empirical evidence presented above, this study poses the following research questions (RQs) on the linkages between social investment policy functions and individual poverty risk:

RQ1. Do stock, flow, and buffer policy functions mitigate the individual poverty risk of men and women depending on age (1a) or family status (1b)?

RQ2. Do stock, flow, and buffer policy functions have complementary impacts on the poverty risk of young adults (2a) and single mothers (2b)?

Policy changes in twenty-first-century Germany

The poverty rates in Germany increased rapidly at the beginning of the twenty-first century (Jenkins and Schluter, Reference Jenkins and Schluter2003; OECD, 2008), compounded by high unemployment and low fertility rates. To tackle these demographic and social issues, Germany took major steps in reforming the welfare state. Previously characterised as the main model for a male-breadwinner system, the German welfare state shifted its focus towards providing stronger support for two-earner families and female employment, boosting the working-age population’s economic activity through active labour market policy reforms (Trzcinski and Camp, Reference Trzcinski, Camp and Robila2014). This article focuses on nine different policies, which are organised into the SI policy functions: Buffers consist of unemployment benefits, housing allowance, and minimum wage; flow function includes parental leave, child allowance, and childcare; and stocks consist of adult education, institutional ALMP training, and non-continuation of compulsory education.Footnote 1

The unemployment benefits represent the social assistance part of the buffer function in Germany, particularly after the Hartz reforms, which took place around the mid-2000s. These reforms implemented a substantial change in unemployment benefits, merging them with social assistance with means-tested criteria and establishing stricter long-term benefits and sanctions (Trzcinski and Camp, Reference Trzcinski, Camp and Robila2014; Seeleib-Kaiser, Reference Seeleib-Kaiser2016). Although some positive returns in employment were observed, the reform also led to deregulating temporary and atypical forms of work, promoting any work over sanctions and increasing in-work poverty (Seeleib-Kaiser, Reference Seeleib-Kaiser2016; Gerlitz, Reference Gerlitz2018). Housing allowance was integrated into the unemployment benefit within the Hartz reforms, making it a benefit for low-income households above the social minimum (Haffner et al., Reference Haffner, Hoekstra, Oxley and van der Heijden2009). The allowance amount was increased in 2009 and again in 2016 to compensate housing costs for people with low incomes (Haffner et al., Reference Haffner, Hoekstra, Oxley and van der Heijden2009; Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy, 2016). A statutory hourly minimum wage was introduced in Germany in 2015 to alleviate poverty. The reform positively impacted low-wage workers, but broader poverty reduction has not been observed (Caliendo et al., Reference Caliendo, Schröder and Wittbrodt2019).

Regarding the flow function, the policies promoting better work-life balance in Germany have seen significant reforms. With more generous and earnings-related pro-dual-earner parental leave reform in 2007 and a significant but gradual increase in ECEC availability for under three-year-olds since 2005, the aim has been to promote maternal employment, reduce inequalities and poverty, and generate ‘sustainable’ human capital for the future (Ostner, Reference Ostner2010; Trzcinski and Camp, Reference Trzcinski, Camp and Robila2014). The parental leave reform has increased mothers’ labour market attachment (Ziefle and Gangl, Reference Ziefle and Gangl2014). On the other hand, child allowances have been stagnant and have suffered from inflation significantly despite an increase in 2010 and some small occasional increases later (Gauthier, Reference Gauthier2011; Raschke, Reference Raschke2012; Sozialpolitik-aktuels.de, 2023). However, the benefit system allows parents to choose between the direct cash benefit of child allowances or a tax deduction, with those who are well-off tending to opt for the latter (Blome et al., Reference Blome, Keck and Alber2009; Van Lancker and Ghysels, Reference Van Lancker and Ghysels2012).

Within the stock function, the German education and training systems have seen reforms in both general adult education and youth-targeted programmes. There have been attempts to reform vocational training towards lifelong learning, yet the system has remained very complex (European Commission, 2022). Overall, the adult education participation rates have been increasing steadily since the 2000s, and as such, it remains a central part of the German stock function (Eurostat, 2022). Although the overall government spending on the training as a part of ALMP has decreased sharply throughout the 2000s, specific programmes and employer subsidies for disadvantaged youth, as well as training programmes for low-skilled and unemployed individuals, were established since the early 2000s to improve employment of marginalised groups and to reduce high poverty rates (European Commission, 2022; OECD, 2023). The training programmes were found to increase educational participation, and the number of young adults without post-compulsory education has decreased steadily since the mid-2000s (Eurostat, 2023). However, the impact of the training programmes was less influential, or more prolonged, for employment returns and hence their influence on reducing the high poverty rates of youth could be in question (Caliendo et al., Reference Caliendo, Künn and Schmidl2011).

Data and methods

Micro-level data and measures

This study used micro-level data from the G-SOEP, an annual longitudinal household panel covering almost 20,000 households. Individuals were observed during the period 2002–18Footnote 2 from age seventeen (the earliest possible age to enter the survey) to sixty, to capture the working-age population (thus excluding children and pensioners). This resulted in a sample comprising over 53,000 individuals and almost 280,000 person-year observations.

The dependent variable is whether an individual was at-risk-of-poverty in a given year. The poverty line is drawn at 60 per cent of the equivalised median disposable household annual income, a commonly used poverty threshold in national and international statistics. Using this threshold enables to examine a population who are not only struggling to meet their basic needs (i.e., in absolute poverty) or to be in deep extreme poverty (i.e., lower poverty threshold), but also includes individuals with lower incomes yet at risk of poverty. The threshold line is measured separately for each year, allowing structural macro-level situations (economic changes, income regulations, etc.) that influence the population-level measure of median income to alter across time (see, e.g., Corak, Reference Corak2006). To capture also the public redistributive element of poverty alleviation, the disposable household income must combine all earnings, transfers, incomes, and pensions of all individuals in a household, with taxes deducted from the sum. Further, it is highly relevant to measure household income that includes transfers and tax revenues, as German families, or married couples in particular, benefit from the public provision through these systems, often excluding single parents (Bonin et al., Reference Bonin, Reuss and Stichnoth2015). However, as the focus of the analyses is on the individual, to compare households of varied sizes, household income is equivalised by the square root of the number of household members (OECD, 2008; UNECE, 2017).

The main independent variables at the individual level relate to demographic factors. Gender is the main variable across all analyses. To examine disadvantaged groups, I used age categories (youth aged seventeen to twenty-nine years, working-age persons thirty to forty-nine years, and older persons fifty to sixty years) to analyse impacts on youth; and to observe the impacts on single mothers, I use information on family types based on partnership and having children under the age of eighteen years in the household.

Control variables include both micro and macro-level variables. Individual-level control variables are educational attainment (primary education, secondary education including abitur and vocational degrees, and higher educational degrees), labour market status (including family leave and marginal work), partnership status (partnered or not), having children under eighteen years of age in the household, immigrant background, region (East/West), and age and age squared. Variables are used to create the main independent variables, i.e., age in the analyses of age groups and youth and partnership and having children in the analyses of family status and single mothers. Gross domestic product (GDP) is also included as a macro-level control to account for economic conditions over time. Other structural measures, such as the unemployment rate, are not considered suitable due to being aggregates derived from the individual situations studied here. Further, I account for the general labour market opportunities by controlling for labour market status and GDP, which is inversely correlated with the unemployment rate. See Table A1 in the Appendix for descriptive statistics of all variables.

Policy function measures

This article aims to study the policy complementarities through social investment policy functions. These are operationalised using nine policy indicators (see Appendix A2 for detailed information and sources), which, based on their main policy function, are categorised into one of three policy packages: buffer, flow, and stock functions. Although each policy indicator could have multiple functions, they have been categorised based on their most substantial intended function. For example, child allowance could be seen as buffering inadequate labour market incomes for families, but because the policy aim is to compensate for the increased costs of child-rearing, often despite their income levels, the flow function is stronger. The policy packages aim to represent various policy types or relate to multiple life stages, yielding measures with extensive coverage of German welfare state policies between 2001Footnote 3 and 2018.

Each policy package aims to capture some of the main policy changes of each policy function in Germany (see the previous section for literature). The buffer package includes policy indicators that alleviate the negative economic impacts of labour market failures and personal events: unemployment benefits (replacement rate after twenty-four months of unemployment), housing allowance (monthly amount), and minimum wage (percentage of median full-time wages). The flow package contains policies that promote work-family balance: parental leave (replacement rate), ECEC (participation rate), and child allowances (monthly amount for a first child). The stock package covers policies that both build and maintain human capital: the rate of early leavers from education (the percentage of young adults with maximum lower secondary education and not currently in education or training); expenditure on institutional training (targeted programmes for disadvantaged groups); and adult education (participation rate).Footnote 4

Given that the exact time of policy changes cannot be pinpointed to ensure the actual policy provision at the time of the interview, the macro variables are lagged by one year (t−1), except for institutional training, which measures annual expenditure, and can be assumed to have a more direct impact on individuals’ poverty risk. Further, the policy indicators are harmonised to be comparable and scaled so that negative values indicate low or weak public provision and positive values indicate high/strong provision. Hence, the repetition and early education leavers rates were modified such that the higher the value, the better.

The policy function packages were created using principal component analysis (PCA), which uses a correlation matrix of the annual information on multiple policy variables, creating only one measure that captures the original over-time variance as much as possible while minimising information loss. The PCA component explains 67.5 per cent of the variance in buffer variables, 73.5 per cent of flow variables and 87.4 per cent of stock variables (see Appendix A3 for the correlation matrices, the eigenvalues and coefficients of the PCA components). The macro variables are standardised to have equal weights in the PCA. Figure 1 presents the annual information of each standardised policy measure and the policy packages across the observation period. Notably, although the policy measures that have been reduced over time (unemployment benefit and institutional training) are not well reflected in the PCA components, higher values of the components can still be interpreted as stronger functions.

Figure 1. Changes in buffer, stock, and flow measures in Germany 2002–18 (variables are harmonised, standardised, and all, except for institutional training, are also lagged for analytical purposes).

Methods

The analyses are based on non-linear logistic regression modelling with clustered standard errors (SEs) by individuals to investigate the probability of individual poverty risk. This methodology allows to examine a phenomenon (poverty) that occurs in only a small portion of the population, i.e., the dependent variable does not vary over time for most individuals. The method acknowledges the longitudinal nature of the data by correcting SEs and enables to analyse both constant (i.e., gender, education, region, and immigrant status) and time-varying (labour market status, partnership status) variables.

The micro-macro modelling examines how the change in the independent variable (aggregate policy function measures) impacts the probability of the outcome (individual poverty risk) among specific demographic groups, accounting for individual-level covariates. In other words, the analytical framing examines cross-level interactions between policy functions and demographic factors such as gender, age, and family type. To examine individual effects within population subgroups, the analyses apply average marginal effects (AMEs).

Although the fixed-effects model would be ideal to counter the unobserved heterogeneity bias, it would drop out individuals who have no over-time change in their poverty risk and hence would not allow the examination of the phenomenon with a partial sample. Further, unlike hierarchical models, this analytical approach enables using cross-sectional individual weights that account for the initial sampling probability and all response probabilities for each survey year, which are crucial when analysing a marginal phenomenon and a population that often has a low participation rate in surveys.

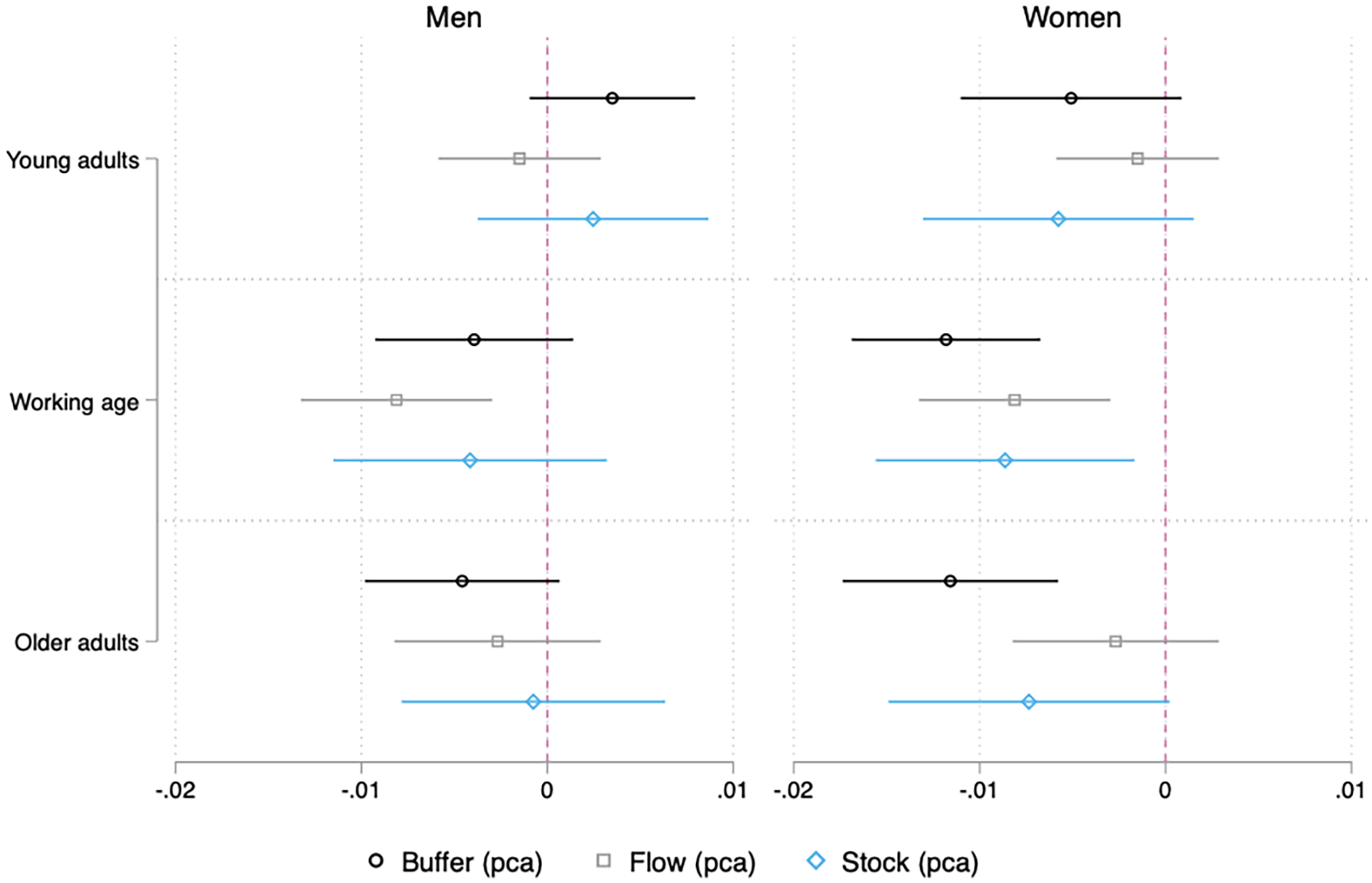

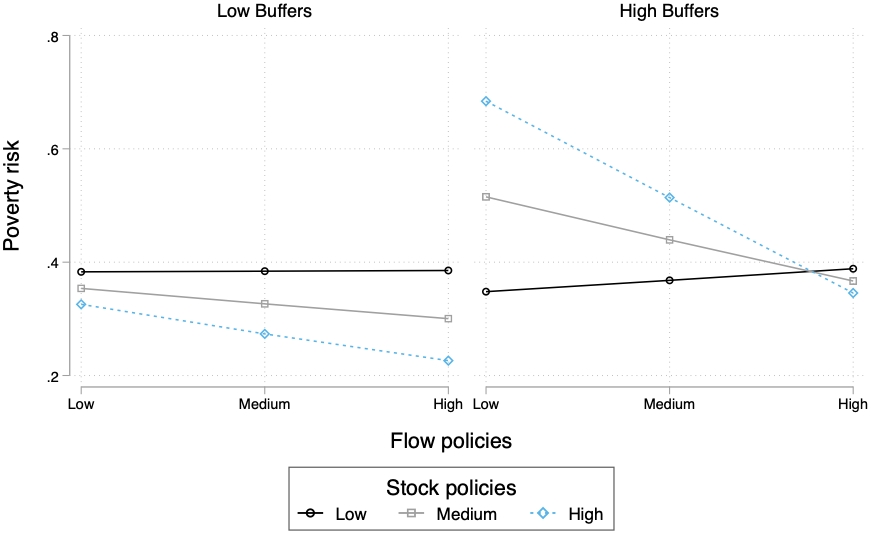

The results are presented separately for each research question. First, the results of the interaction effects between the policy functions and age group (Figure 2) or family status (Figure 4) are presented as AME graphs from a logistic regression model with a complete set of controls for men and women separately (see Appendix A4 for tabled AME results of the figures and for AME graphs of individual policies). All models control for the other SI policy functions than the policy in focus to derive more apparent impacts for each policy. Using AMEs enables a clearer interpretation of the logistic regression coefficients and mitigates issues related to comparing different logistic regression models (Breen et al., Reference Breen, Karlson and Holm2018). Second, the policy complementarity effects, namely interaction effects between all the policy functions, are presented as predicted probabilities of flow and stock functions at low and high levels of buffer functions among young adults (Figure 3) or among single mothers (Figure 5). Low buffers reflect the values below, and high buffers above the median value, reflecting 2002–11 and 2012–18, respectively. In these graphs, confidence intervals (CIs) are omitted to emphasise the general associations and differences instead of statistically significant differences across (small) groups to clarify interpretation. Appendix A5 includes the tabled results of all regression models focusing on policy functions.

Figure 2. Impacts of SI policy functions on poverty risk by age group and gender (AMEs of separate logistic regression models with clustered SEs).

Figure 3. Policy complementarities on the poverty risk among young (17–29 years) men and women separately for low (2002–11) and high buffers (2012–18) (predicted probabilities of logistic regression models with clustered SEs, CIs omitted).

Figure 4. Impacts of SI policy functions on poverty risk by family type and gender (AMEs of separate logistic regression models with clustered SEs).

Figure 5. Policy complementarities on the poverty risk of single mothers, separately for low (2002–11) and high buffers (2012–18) (predicted probabilities of logistic regression models, CIs omitted).

Approximately 21 per cent of the analytical sample is from East Germany; hence, as a robustness check, the analyses were run for West Germany only. The results were very similar to those presented below for the total sample. Since policies are measured after unification, and most policies are implemented at the national level, including the sample from East Germany increased the robustness and generalisability of the results on policy impacts.

Results

Policy function impacts across age groups

Figure 2 visualises the interaction effects between policy functions and age groups for men and women separately (RQ1a). The clearest poverty alleviation impact is found among women at all ages, and particularly of working age, as all policy functions reduce their poverty risk. The flow function is found to reduce the poverty risk of working-age men as well. These positive poverty returns at working age suggest that the flow function is successful in promoting work-life balance. However, this positive impact is less evident among young adults, indicating that young families do not benefit from this support to the same degree. Further, in relation to buffer and stock function, the results demonstrate differing impacts between young men and women. While all policy functions are found to reduce young women’s poverty risk, among young men, buffer and stock functions are found to reinforce the poverty risk (although statistical significance is weak).

Policy complementarities among young adults

Figure 3 demonstrates the policy complementarity impacts of the SI policy functions among young men and women (RQ2a). The results show that when the buffer function is weak, strong stock and flow functions together reduce the poverty risk, although this is rather minor among men. Once the buffer function is secured, men are found to benefit from the substitutive effect; if the flow function is strong, the stock function seems to matter less, whereas when the flow function is weak, the strong stock function can substitute and reduce men’s poverty risk. This means educational policies can provide poverty alleviation when family support is inadequate for young men, as long as buffers are strong. Among young women, policy complementarities are more dependent on the strength of the flow function; the poverty risk is lower when the flow function is strong, independent of the buffer function, but strengthened with a strong stock function. However, when the flow function is weak and the stock function strong, young women seem to be at a disadvantage, suggesting that educational investment without family support is not only unable to alleviate young women’s poverty risk but may create educational traps to escape from poverty despite strong buffer policies.

Policy impacts across family types

Figure 4 shows the poverty returns to the policy functions among single and partnered women and men with and without children living in their households (RQ1b). Again, the results show the strongest positive poverty returns among women, single mothers benefiting the most from all policy functions. Buffer and stock functions are found to reduce the poverty risk of women in all family types, although the latter is not statistically significant for all. Among men, the policy functions are found to reduce poverty only of partnered men with children. This is in contrast to the negative impact of flow function (although not statistically significant) among single men, highlighting the strong male breadwinner focus of the German welfare state. Additionally, the flow function is found to reduce single fathers’ poverty risk, although to a slightly lower degree than that of single mothers, yet pointing to strong family support for one-parent families.

Policy complementarities among single mothers

Figure 5 demonstrates the policy complementarities of stock and flow policies during low (2002–11) and high (2012–18) buffer levels among single mothers (RQ2b). Similar to Figure 3, the results indicate a combined positive impact of strong flow and stock policies when the buffer function is low, providing an optimistic scenario of substitution effects if income protection is inadequate. With strong traditional poverty alleviation buffers, strong family support is key to poverty alleviation among single mothers; if they are weak, stock function has no poverty reduction impact. Again, a high stock function associated with weak family support may create a labour market disadvantage for single mothers, increasing their poverty risk.

Discussion and conclusions

This study examines the association between social investment policy functions and poverty risk among German individuals and families during the first two decades of the twenty-first century. By measuring welfare state institutions based on their policy functions, namely stocks, flows, and buffers, this research provides empirical evidence regarding how policy complementarities influence the poverty risk of different demographic groups. The results show variation of impacts across age groups, family types, gender, and the functions. Among women, the policy functions are found to alleviate the poverty risk, particularly among single mothers and at working age. Among men, the policy functions alleviate the poverty risk mainly of fathers in two-parent households.

Alarmingly, the results indicate that the policy functions are inadequate in addressing the prevalent poverty risk of young adults, particularly of young men; buffer and stock policies, which aim at reducing vulnerable and unstable labour market situations, are not found to reduce the poverty of young men, and only very weakly of young women. This finding echoes the recent criticism of ignoring youth in welfare policies and ALMPs (Cefalo and Scandurra, Reference Cefalo and Scandurra2023; European Commission, 2023). Considering there are various life-course transitions during this life stage, such as school-to-work, leaving home, family formation, and attaining sufficient labour market standing, and only unemployment benefits are found to have any indication of poverty alleviation, it is possible that public policies are not capable of addressing sufficiently individual needs of young men. While family support is the only policy function presenting poverty alleviation impact alone on poverty of young men, the joint impact of strong income compensation buffers and educational stock policies is found to create positive policy complementarities in poverty returns. The investments in education, however, are less impactful if buffers are weak, raising the importance of financial compensation while promoting human capital advancement of young men. These results highlight the importance of addressing multiple needs simultaneously to support young men in risky life situations.

Family support (flow function) is found to be central in poverty alleviation in Germany. It is found to reduce the poverty risk of single mothers and fathers, and generally of working-age men and women. Child allowances are found to be particularly beneficial for working-age poverty risk, whereas all flow function policies diminished single mothers’ poverty risk (see Appendix A4). Overall, a strong flow function is found to be a prerequisite for the policy complementarities in single mothers’ poverty alleviation. These findings suggest that the changes towards ‘sustainable family policies’ in the twenty-first century (Ostner, Reference Ostner2010) have been successful in addressing the needs of families in vulnerable situations and of the increased female employment. However, the shift towards two-earner families in Germany has not resulted in a less-persistent male-breadwinner culture, as the results show that among two-parent households, family policies only benefit men, not women. This raises a question whether the underlying gender inequalities in women’s labour market attainment, care burden, and family culture are yet to be transformed, or are we unable to examine the impacts of such recent societal shifts in policies.

The results regarding the interplay between the SI policy function packages show reinforcement effects between stock and flow policy functions if social protection buffers were weak. This brings light to the possibilities of social investment policies also in settings where social protection buffers may be inadequate in poverty alleviation. Similar positive returns, although with two-way interaction of policies, have been found in relation to employment (Nieuwenhuis, Reference Nieuwenhuis2022 on ECEC and ALMP; Plavgo, Reference Plavgo2023 on education and ALMP). In other words, if traditional poverty alleviation measures, i.e., social protection, fail, policies that promote wellbeing more comprehensively through stable labour market transitions, human capital promotion, and family support can step up to decrease the risk of disadvantaged groups, here young adults and single mothers, from being in poverty. Furthermore, a cumulative policy impact is found if buffers are strong; signalling that if social protection is adequate, social investment stock and flow policies are able to reduce individual poverty risk even better.

Germany, like many other European countries, has gone through a transformation of female employment, labour market dualisation, and increasing inequalities. In addition to the successful family policy changes discussed above, another key element for poverty alleviation, and the current demographic challenges, is education. Considering the strong educational tracking of the German educational system and strong apprenticeship traits, the results demonstrate that women’s poverty risk is lower with higher educational attainment levels and adult education participation. ALMP training programmes, on the other hand, are found to negatively impact poverty across all demographic groups (see Appendix A4), highlighting the importance of investment in general educational systems and in life-long learning instead of activation through training. Moreover, this would address the disadvantages of low-skilled workers and increasing inequalities while enhancing gender equality.

This study examined policy complementarities on two levels. First, policies were categorised into policy packages based on their main function. The separate policy results (Appendix A4) demonstrate that the packages reflected relatively well the policy-specific impacts on poverty. Although the interaction effects are relatively small, the policy function impacts seem to have better statistical power and smaller SEs than individual policies, making the policy package a more robust measure than one policy indicator. Further, using complementarity measures of policies facilitates easier generalisation to other country contexts, but it leaves out the possibility of pinpointing which exact policies or provisions are behind the results. However, this would be analytically robust mainly with a causal framework of policy reforms in certain settings, which would not, in turn, allow a broader generalisation of the policy impact results. The traditional middle way of using social expenditure data, often in comparative settings, allows broader generalisation but lacks the nuance of policies, as spending indicators do not show what kind of policies they contain, and whether changes in spending are due to changes in policies or in demographics. Therefore, I argue that analysing policy impacts through a complementary approach using detailed policy indicators brings a new way of examining the relationship between social realities and the welfare state.

The findings demonstrate that all policy functions reduce the poverty risk among single mothers, one of the central demographic groups in poverty alleviation, which contributes to the recent discussion about whether social investment policies are adequate in safeguarding the livelihoods of society’s most disadvantaged groups (Vandenbroucke and Vleminckx, Reference Vandenbroucke and Vleminckx2011; Cantillon and Van Lancker, Reference Cantillon and van Lancker2013). However, the focus on young adults and single parents as risk groups may leave out other important demographic groups, such as long-term unemployed or disabled, from the poverty alleviation framework. Hence, it would be important for future research to examine the impacts of policies, from a complementarity perspective, to disentangle how and which policies are most suitable in diminishing poverty risk in different life situations.

In conclusion, with recognition of the varying needs of men and women in different life stages and situations, the German welfare state should put more effort into the efficiency of educational and ALMP policies for young men. Overall, the policy complementarity results of this article, both in terms of policy function packages and interaction effects between the functions, indicate that policies are most effective in tackling poverty when individual life settings and social issues are addressed comprehensively. No one policy alone can diminish poverty. Investing in educational policies to diminish precarious labour market situations, providing adequate social protection at times of need, and supporting families together, not as alternative or separate policy options, would increase the wellbeing of the whole adult population, creating resilient welfare states for the future changes in the labour markets due to ageing societies.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material of Appendices A1-A5 for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474746425101309.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Wellbeing Returns to Social Investment (WellSIre) – project (European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme, grant agreement No 882276) and INVEST Research Flagship Center (Research Council of Finland, decision number 345546). The author thanks all involved project members and sends gratitude also to the participants who provided fruitful comments and feedback for the earlier versions of this paper in EspaNET 2022 Vienna Conference, ISA RC19 Annual Meeting 2922, and the Social Investment Working Group of the EUI.

Funding statement

This paper was funded by WellSIre – project (European Research Council under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme, grant agreement No 882276) and by INVEST Research Flagship Center (Research Council of Finland, decision number: 345546).

Competing interests

The author declares none.