Introduction

The genus Hepatozoon (Hepatozoidae) encompasses hundreds of described species, representing the most abundant and diverse haemogregarine group within the phylum Apicomplexa (Smith, Reference Smith1996; Maia et al., Reference Maia, Carranza and Harris2016; Votýpka et al., Reference Votýpka, Modrý, Oborník, Slapeta, Lukes, Archibald, Simpson and Slamovits2017). The life cycle of these parasites is heteroxenous, involving haematophagous invertebrates as both vectors and definitive hosts, and one or more vertebrates as intermediate hosts (Votýpka et al., Reference Votýpka, Modrý, Oborník, Slapeta, Lukes, Archibald, Simpson and Slamovits2017). The range of vertebrate hosts is wide, from fish to mammals (Telford, Reference Telford2009; Cardoso et al., Reference Cardoso, Perles, Picelli, Correa, André and Viana2022; Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Santodomingo, Saboya-Acosta, Quintero-Galvis, Moreno, Uribe and Muñoz-Leal2024). These parasites are ubiquitous in snakes, in which they can be observed as gamonts, primarily in erythrocytes, and meronts in the liver, lungs, kidneys, spleen and other viscera (Telford, Reference Telford2009).

For over a century, Hepatozoon spp. of snakes have been described based solely on morphological and morphometric data of intraerythrocytic and tissue stages, primarily gamonts (Carini, Reference Carini1910; Telford, Reference Telford2009). However, morphological characterization alone may be insufficient to distinguish species and can lead to synonymy (Zechmeisterová et al., Reference Zechmeisterová, Javanbakht, Kvicerová and Siroký2021). Compared to the long history of morphological descriptions, the molecular characterization of Hepatozoon species is still a recent development, beginning with the parasite’s characterization through the nuclear ribosomal 18S gene (Sloboda et al., Reference Sloboda, Kamler, Bulantová, Votýpka and Modrý2007). Since then, many species have been described using a combination of morphological and molecular data (Maia et al., Reference Maia, Carranza and Harris2016; Zechmeisterová et al., Reference Zechmeisterová, Javanbakht, Kvicerová and Siroký2021).

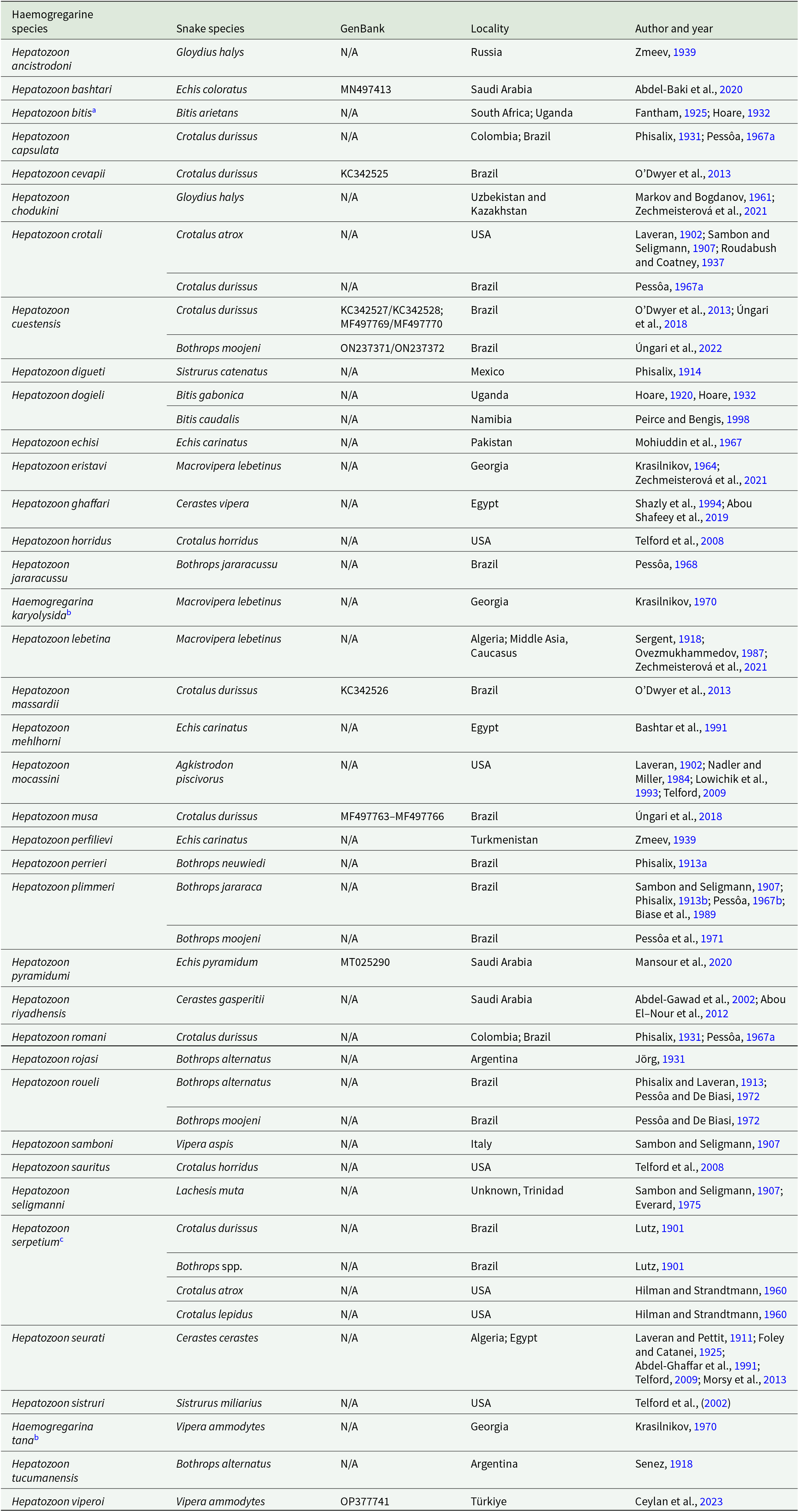

Approximately 150 species of Hepatozoon have been described in several snake species worldwide (Smith, Reference Smith1996; Telford, Reference Telford2009, Reference Telford2010; Telford et al., Reference Telford, Moler and Butler2012; O’Dwyer et al., Reference O’Dwyer, Moço, Paduan, Spenassatto, Silva and Ribolla2013; Abdel-Baki et al., Reference Abdel-Baki, Al-Quraishy and Zhang2014, Reference Abdel-Baki, Mansour, Al-Malki, Al-Quraishy and Abdel-Haleem2020; Han et al., Reference Han, Wu, Dong, Zhu, Li, Zhao, Wu, Pei, Wang and Huang2015; Borges-Nojosa et al., Reference Borges-Nojosa, Borges-Leite, Maia, Zanchi-Silva, da Rocha and Harris2017; Cook et al., Reference Cook, Netherlands, Smit and Van As2018; Mansour et al., Reference Mansour, Abdel-Haleem, Al-Malki, Al-Quraishy and Abdel-Baki2020; Úngari et al., Reference Úngari, Netherlands, De Alcantara, Emmerich and Da Silva2021a, Reference Úngari, Netherlands, Santos, De Alcantara, Emmerich, Da Silva and O’Dwyer2022; Ceylan et al., Reference Ceylan, Úngari, Sönmez, Gul, Ceylan, Tosunoglu, Baycan, O’Dwyer and Sevinc2023; Picelli et al., Reference Picelli, Silva, Correa, Paiva, Paula, Hernández-Ruz, Oliveira and Viana2023). Notably, the family Viperidae harbours a relatively high diversity of Hepatozoon spp., accounting for 25% of all described species (n = 38/150 spp.). These parasites have been recorded in 26 viperid snake species distributed across the Americas, Africa, Asia and Europe (Table 1). Most of these descriptions rely on morphological data; indeed, only seven species (18%; n = 38 spp.) have undergone molecular characterization, of which four are from two snake species, Crotalus durissus Linnaeus, 1758 and Bothrops moojeni Hoge, 1966, from southeastern Brazil (Table 1).

Table 1. A checklist of Hepatozoon species records in viperid snakes, with GenBank accession numbers, localities and references

a Considered a synonym of H. dogieli by Peirce and Bengis (Reference Peirce and Bengis1998).

b Species not included in previous reviews (see Levine 1988 and Smith, Reference Smith1996).

c Lutz (Reference Lutz1901) classified haemogregarines with distinct morphologies from several snake species as belonging to this same species, it is most likely not a valid species.

The Amazonia region has the greatest diversity of snakes in Brazil, including 12 of the 34 viperid species found in the country (Nogueira et al., Reference Nogueira, Argôlo, Arzamendia, Azevedo, Barbo, Bérnils, Bolochio, Borges-Martins, Brasil-Godinho, Braz, Buononato, Cisneros-Heredia, Colli, Costa, Franco, Giraudo, Gonzalez, Guedes, Hoogmoed, Marques, Montingelli, Passos, Prudente, Rivas, Sanchez, Serrano, Silva, Strüssmann, Vieira-Alencar, Zaher, Sawaya and Martins2019; Costa et al., Reference Costa, Guedes and Bérnils2022). These venomous snakes are particularly noteworthy in the region due to their frequent involvement in snakebite accidents, especially the common lancehead snake Bothrops atrox (Linnaeus, 1758), which is considered the most medically important species in cases of human envenomation (Monteiro et al., Reference Monteiro, Contreras-Bernal, Bisneto, Sachett, Da Silva, Lacerda, Costa, Val, Brasileiro, Sartim, Silva-de-oliveira, Bernarde, Kaefer, Grazziotin, Wen and Moura-da-silva2020). Furthermore, despite records of 10 species of Hepatozoon in Brazilian viperids (Table 1), there are no reports of these parasites in Viperidae snakes from the Amazonia region until now.

In this way, our study aimed to investigate the presence of haemogregarines in the common lancehead snake from Eastern Amazonia, Brazil. Through the combination of morphological, morphometric and phylogenetic analyses, we described a new species, namely Hepatozoon atrocis sp. nov., infecting the blood and tissues of B. atrox.

Materials and methods

Sampling and morphological identification

One common lancehead snake (B. atrox) was captured in the urban area (0°00’59.17” S and 51°04’43.39” W) of the municipality of Macapá, State of Amapá, Brazil. After restraining the snake, blood samples were collected by caudal venipuncture using sterile 1 mL insulin syringes (Sykes and Klaphake, Reference Sykes and Klaphake2008). Thin blood smears were performed, air-dried, fixed with absolute methanol for 3 min, and stained with 10% Giemsa for 30 min (Hull and Camin, Reference Hull and Camin1960; Telford et al., Reference Telford, Wozniak and Butler2001). Part of the blood sampled was stored in microtubes with 96% ethanol.

To describe the parasite stages in tissues, the snake was euthanized with the intravenous anaesthetic Pentobarbital 60–100 mg kg−1 and monitored until death was confirmed, following the guidelines of the Animal Ethics Committee for Veterinary Medicine (Conselho Nacional de Controle de Experimentação Animal (CONCEA), 2018). The snake was deposited as voucher material in the collection of the Laboratório de Herpetologia, Universidade Federal do Amapá, Brazil (no 4010). The liver, lungs, heart, large intestine and kidneys were collected and fixed in 10% buffered formalin to prepare histological sections. Slides were cut at 5 µm and stained with haematoxylin-eosin (Paperna and Lainson, Reference Paperna and Lainson2004).

The blood smears and histological sections were screened under a light microscope at ×100, ×400 and ×1000 magnifications. The parasitic forms were recorded with a 5.1 MP digital camera coupled to the DI-136T biological microscope. The images and measurements of the parasites were processed using Image View® Software. The morphometric characterization of the parasite stages in blood and tissues was given in micrometres (µm), and the variables, such as length, width and area of the parasite and host cell, were presented as mean, amplitude and standard deviation. Parasitemia was estimated by counting the number of parasites visualized in 2000 erythrocytes, in 20 fields of 100 erythrocytes examined (Godfrey et al., Reference Godfrey, Fedynich and Pence1987).

DNA extraction, amplification and sequencing

DNA was extracted using the BIOPUR Mini Spin DNA/RNA extraction kit (Mobius Life Science, Pinhais, Brazil). The detection of Hepatozoon spp. DNA by PCR (polymerase chain reaction) was performed using the primers HEP-300 (5’-ATACATGAGCAAATCTCAAC-3’) (Ujvari et al., Reference Ujvari, Madsen and Olsson2004) and ER (5’-CTTGGCCTACTAGGCATTC) (Kvicerova et al., Reference Kvicerova, Pakandl and Hypša2008) that amplified a fragment of ≈1200 base pairs (bp) of the 18S rRNA gene. For the HepF300 and ER primer set, the PCR conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95°C for 3 min, followed by 35 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, with an annealing temperature of 60°C for 30 s, and an extension of 72°C for 2 min; and following the cycles a final extension step of 72°C for 10 min.

The amplicon was purified using Wizard® SV Gel and PCR Clean-Up System, following the manufacturer’s protocol. The PCR product was sequenced using the BigDye™ Terminator v.3.1 Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and the ABI 3100 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Considering that the obtained sequence showed multiple peaks in the electropherogram, the amplicon was cloned into pGEM-T Easy (Promega® Madison, WI, USA), following the manufacturer’s recommendations. Six clones were selected according to the blue/white colony system. Colonies with the gene fragment of interest confirmed by PCR were subjected to plasmid DNA extraction using the Wizard® Plus SV Minipreps DNA Purification Systems (Promega Madison, Wisconsin, USA). Subsequently, plasmids were sent for sequencing with the primers M13 F (5′-CGCCAGGGTTTTCCCAGTCACGAC3′) and M13 R (5′GTCATAGCTGTTTCCTGTGTGA-3′) (Lau et al., Reference Lau, Cereceres, Palmer, Fretwell, Pedroni, Mosqueda and McElwain2010) that flank the pGEM-T Easy plasmid multiple cloning site. Furthermore, a pair of internal primers (F: 5’-TTGTTGCAGTTAAAAGTCCG-3’ and R: 5’-AACCAGACAAATCACTCCAC-3’) was designed in the present study and was also used to obtain better sequencing results. Sequencing was performed as described above.

Phylogenetic analysis

An alignment was performed to estimate phylogenetic relationships by Maximum Likelihood (ML) among the three Hepatozoon spp. cloned sequences obtained in this study and those available in GenBank® using BLASTn (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST). This alignment was constructed using the MUSCLE algorithm, available in MEGA X (Kumar et al., Reference Kumar, Stecher and Tamura2016). The database included a total of 60 18S rRNA sequences. Representative sequences of the following taxa were included: Hepatozoon sp. (n = 51), Karyolysus sp. (n = 2), Hemolivia sp. (n = 2), Dactylosoma sp. (n = 1), Haemogregarina (n = 2) and Adelina sp. (n = 2), the latter used as an outgroup. In the ML method, JModelTest version 2.1.10 was used to identify the best evolutionary model (Darriba et al., Reference Darriba, Taboada, Doallo and Posada2012). Based on the Akaike information criterion, the best model for the data was TVM + I + G. The phylogeny was inferred using the PhyML 3.0 software (Guindon et al., Reference Guindon, Delsuc, Dufayard and Gascuel2009), and the reliability of the phylogenetic relationships was evaluated in 1000 replications by the statistical calculation of the bootstrapping method (Felsenstein, Reference Felsenstein1985). The pairwise distance (p-distance) was performed by the MEGA X software, which generated a matrix to compare the interspecific divergence among Hepatozoon spp. cloned sequences from the present study, Hepatozoon sp. (OM033664) from Monodelphis domestica (Wagner, 1842), Hepatozoon sp. (MG437271) from Amblyomma dissimile Koch, 1844, and Hepatozoon spp. sequences previously detected in Brazilian herpetofauna.

Results

Through microscopy screening, different stages of Hepatozoon, such as gamonts, meronts and dizoic cysts, were detected in blood smears and tissue sections of B. atrox. Morphological and phylogenetic analysis supported the proposal of a new species of Hepatozoon.

Species description

Taxonomic summary

Phylum Apicomplexa Levine, 1970

Class Conoidasida Levine,1988

Subclass Coccidia Leuckart, 1879

Order Eucoccidiorida Léger, 1911

Suborder Adeleorina Léger, 1911

Family Hepatozoidae Wenyon, 1926.

Genus Hepatozoon Miller, 1908.

Hepatozoon atrocis sp. nov. Paula, Picelli, Viana and Pessoa

Type host: Bothrops atrox (Linnaeus, 1758) (Squamata: Viperidae).

Vector: Unknown.

Type locality: Josmar Pinto Highway (AP-010), Ramal São Francisco, municipality of Macapá, Amapá, Brazil (0°00’59.17” S, 51°04’43.39” W).

Site of infection: Gamonts in blood erythrocytes; meronts in liver and intestine; dizoic cyst in intestine.

Parasitemia: 28 parasites /2000 blood erythrocytes (1·4%).

Etymology: The specific epithet ‘atrocis’ of Hepatozoon atrocis sp. nov. refers to the species name of the infected host, Bothrops atrox. This is the first Hepatozoon species described in B. atrox.

Type material: Two blood smear slides (hapantotypes) from B. atrox were deposited at the Coleção de Protozoários – COLPROT, an institutional collection of the Fundação Oswaldo Cruz Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (COLPROT 1019).

DNA sequences: The 18S ribosomal gene sequences (1305, 1253 and 1259 bp) were deposited in GenBank® (accession numbers PQ641575, PQ641576 and PQ641577).

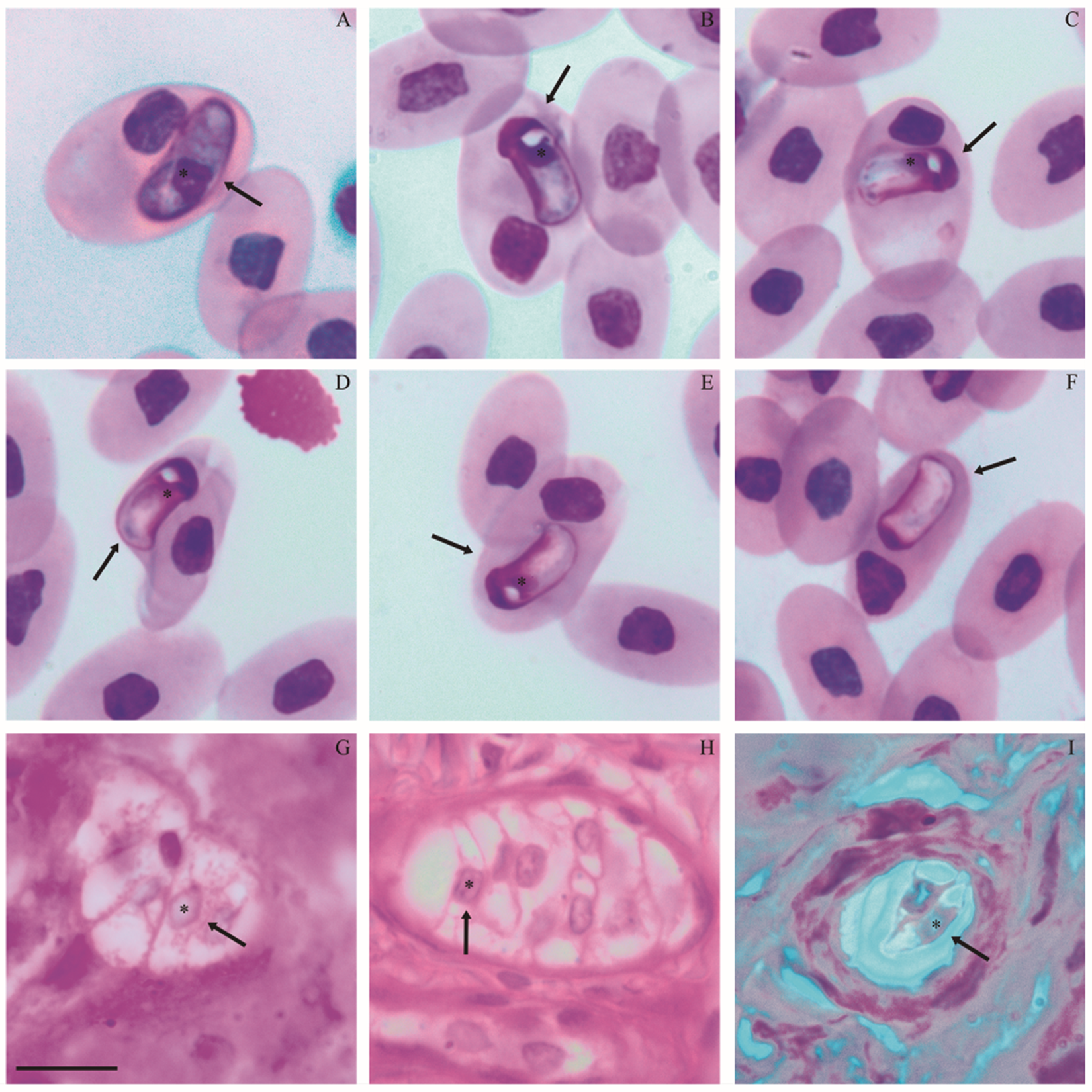

Diagnosis: Blood stages (Figure 1A–F; Table 2) – two morphotypes of mature gamonts were observed. Mature gamonts 1 (Figure 1A; Table 2). Elongated and wide, slightly arched, with rounded ends, one of which is more curved. Uniform cytoplasm stained in purple. The square nucleus with condensed dark purple chromatin is slightly displaced toward the curved end. Mature gamonts 2 (Figure 1B–F; Table 2). Compact body, arched ends, scattered cytoplasm stained in light purple in the middle of the body and dark purple at the ends. One end has a clear, rounded space, similar to a vacuole, near the nucleus. The nucleus is located near one end, with condensed or slightly dispersed chromatin, stained dark purple or pinkish purple, often without a defined shape (Figure 1D and E), and sometimes absent (encapsulated; Figure 1F). The parasitophorous vacuole is slightly evident in mature gamont 1 (Figure 1A) and not visible in mature gamont 2.

Figure 1. Parasitic forms of Hepatozoon atrocis sp. nov. in the snake Bothrops atrox from the Eastern Amazonia, Brazil. Blood smear with mature intraerythrocytic gamonts 1 (A) and 2 (B–F), including encapsulated forms (F). Histological sections of liver and intestine fragments with macromeronts (G, H) and dizoic cyst (I), respectively. Arrows indicate parasites. An asterisk indicates the parasite nucleus. The scale bar for all micrographs is 10 μm.

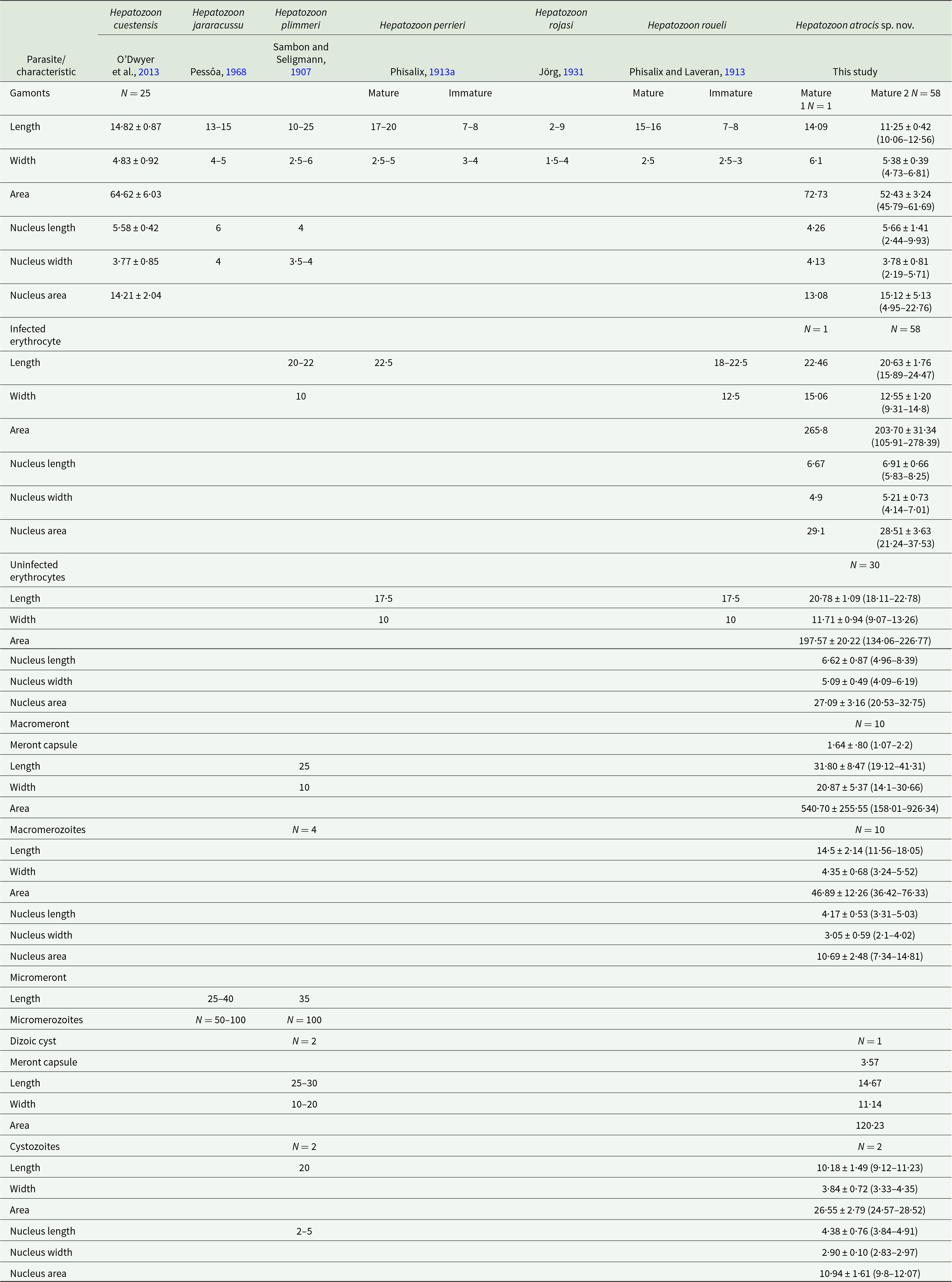

Table 2. Comparative morphometry of blood and tissue stages of Hepatozoon spp. in snakes Bothrops spp. from South America. Measurements are in micrometres and presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and ranges (minimum and maximum values)

Tissue stages (Figure 1G–I; Table 2) – Merogony: Ten macromeronts in the liver and intestine, and 1 dizoic cyst in the intestine. Macromeronts (Figure 1G and H; Table 2). Large and wide, with a thin capsule, stained pink, sometimes ovoid or irregular in shape; containing 4–10 elongated macromerozoites with one of the ends more tapered than the other. The nuclei of macromerozoites are rounded and densely purple-stained. Dizoic cyst (Figure 1I; Table 2): ovoid, stained light pink with a well-developed capsule, containing 2 elongated cystozoites slightly tapered at both ends. The nuclei are long and rectangular, and stained light purple.

Effects on the host cell: Both mature gamonts produce noticeable effects in infected erythrocytes. Parasitized host cells were slightly hypertrophied, with their nuclei displaced to one of the extremities or margins of the host cell (Table 2).

Remarks: There are eight species of Hepatozoon described in Bothrops spp. in South America, six in Brazil, and two in Argentina (Tables 1 and 2). The first record was Drepanidium serpentium by Lutz in (Lutz, Reference Lutz1901), first renamed by Sambon (1907) as Haemogregarina serpentium and later renamed by Smith (Reference Smith1996) as Hepatozoon serpentium (Lutz, Reference Lutz1901). However, H. serpentium is likely not a valid species, as it was poorly described based on different gamont morphologies from several snake species, thus making any comparison with H. atrocis sp. nov. difficult (Lutz, Reference Lutz1901; Picelli et al., Reference Picelli, Silva, Correa, Paiva, Paula, Hernández-Ruz, Oliveira and Viana2023). As the host identity and type locality for H. serpentium are not known and multiple species of Hepatozoon exist in South America, the identity of this species is unlikely to be established; therefore, we place Hepatozoon serpentium in the Nomen dubium here. Hepatozoon plimmeri (Sambon and Seligmann, Reference Sambon and Seligmann1907) from Bothrops jararaca (Wied, 1824) and B. moojeni possess claviform or rounded gamonts that are smaller and thinner or more elongated compared to H. atrocis sp. nov. (Phisalix, Reference Phisalix1913b; Pessôa, Reference Pessôa1967b; Pessôa et al., Reference Pessôa, Belluomini, De Biasi and De Souza1971) (Table 2). One macromeront in an early stage of development of H. plimmeri has been reported, presenting a granular mass and 4 nuclei (Phisalix, Reference Phisalix1913b). Dizoic cysts of H. plimmeri were also observed, which were ovoid, like those of H. atrocis sp. nov., but with larger dimensions (Phisalix, Reference Phisalix1913b) (Table 2). Hepatozoon perrieri (Phisalix, 1913) described in Bothrops neuwiedi Wagler, 1824, has young, small, ovoid gamonts that are smaller than H. atrocis sp. nov. (Table 2). It also has mature gamonts that are elongated, cylindrical and with rounded ends, longer and thinner than H. atrocis sp. nov. (Phisalix, Reference Phisalix1913a; Table 2). Hepatozoon jararacussu (Pessôa, Reference Pessôa1968) of Bothrops jararacussu Lacerda, 1884 has more elongated and thinner vermiform gamonts compared to H. atrocis sp. nov., with one rounded end and the other more tapered and curved (Pessôa, Reference Pessôa1968; Table 2). Hepatozoon roueli (Phisalix and Laveran, Reference Phisalix and Laveran1913) from Bothrops alternatus Duméril, Bibron and Duméril, 1854 and B. moojeni present smaller ovoid gamonts and larger elongated and tapered vermicular gamonts than H. atrocis sp. nov. (Phisalix and Laveran, Reference Phisalix and Laveran1913; Pessôa and De Biasi, Reference Pessôa and De Biasi1972) (Table 2). Hepatozoon rojasi (Jörg, Reference Jörg1931) and Hepatozoon tucumanensis (Senez, Reference Senez1918) were both identified in B. alternatus and differ from the parasite found in the present study. Gamonts of H. rojasi exhibit various morphologies, which vary from elongated to short and can be cylindrical, curved, or fusiform. Their measurements demonstrate that they are smaller than the gamonts of H. atrocis sp. nov. (Jörg, Reference Jörg1931) (Table 2). Gamonts of H. tucumanensis are slightly curved with rounded ends; the morphometric data are unavailable for this species, thus preventing a comparison with H. atrocis sp. nov. (Senez, Reference Senez1918). Hepatozoon cuestensis (O’Dwyer et al., Reference O’Dwyer, Moço, Paduan, Spenassatto, Silva and Ribolla2013), which infects B. moojeni, is the only species with available molecular data and is phylogenetically related to H. atrocis sp. nov. Its gamonts differ from H. atrocis sp. nov. by being more elongated and thinner (Úngari et al., Reference Úngari, Netherlands, Santos, De Alcantara, Emmerich, Da Silva and O’Dwyer2022) (Table 2). Four Hepatozoon species were phylogenetically related to H. atrocis sp. nov., namely Hepatozoon musa (Borges-Nojosa et al., Reference Borges-Nojosa, Borges-Leite, Maia, Zanchi-Silva, da Rocha and Harris2017) from the snake Philodryas nattereri Steindachner, 1870; Hepatozoon odwyerae (Picelli et al., Reference Picelli, Silva, Correa, Paiva, Paula, Hernández-Ruz, Oliveira and Viana2023) from the snake Drymarchon corais (Boie,1827); Hepatozoon ameivae (Carini and Rudolphi, 1912) from the lizard Ameiva ameiva (Linnaeus, 1758); and Hepatozoon trigeminum Úngari, Netherlands, Silva and O’Dwyer, 2022 from Oxyrhopus trigeminus Duméril, Bibron and Duméril, 1854. Gamonts of both H. musa, H. odwyerae, H. ameivae and H. trigeminum are longer and thinner (LW 18·9 ± 0·9 × 3·8 ± 0·3 μm; LW 13·41 ± 0·79 × 3·72 ± 0·35 μm; LW 14·28 ± 1·05 × 4·5 ± 0·8; LW 14·64 ± 0·58 × 5·65 ± 1·21 μm, respectively) than most gamonts of H. atrocis sp. nov. (Borges-Nojosa et al., Reference Borges-Nojosa, Borges-Leite, Maia, Zanchi-Silva, da Rocha and Harris2017; Picelli et al., Reference Picelli, Silva, Ramires, da Silva, Pessoa, Viana and Kaefer2020, Reference Picelli, Silva, Correa, Paiva, Paula, Hernández-Ruz, Oliveira and Viana2023; Úngari et al., Reference Úngari, Netherlands, Santos, De Alcantara, Emmerich, Da Silva and O’Dwyer2022) (Table 2). In tissue stages, H. trigeminum had small and ovoid macromeronts (LW 19·19 ± 1·87 × 21·25 ± 2·32 μm), and elongated macromerozoites with similar dimensions (LW 15·30 ± 0·79 × 4·42 ± 0·22 μm) (Úngari et al., Reference Úngari, Netherlands, Santos, De Alcantara, Emmerich, Da Silva and O’Dwyer2022) to those of H. atrocis sp. nov. (Table 2).

Molecular and phylogenetic analysis

Three 18S rRNA cloned sequences of H. atrocis sp. nov. were obtained from the single individual of B. atrox and presented fragments of 1305 (PQ641575), 1253 (PQ641576) and 1259 (PQ641577) bp. One (PQ641575) of the three novel sequences differed by 0·2% when compared to the other two cloned sequences (PQ641576 and PQ641577), thus indicating the presence of two haplotypes (H1 [PQ641575] and H2 [PQ641576 and PQ641577]) (Supplementary Material 1).

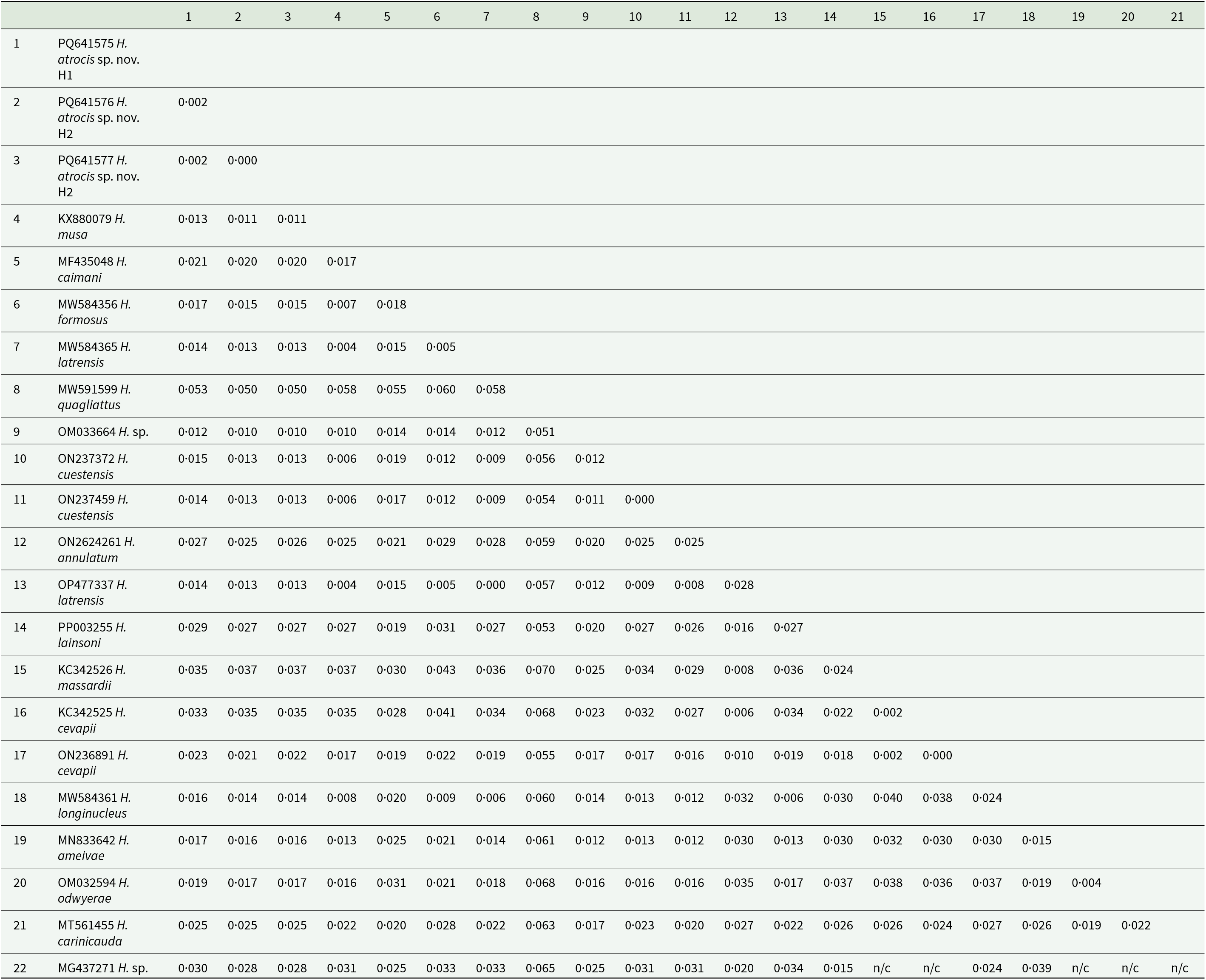

The sequences detected in B. atrox exhibited BLASTn identity of 98·93–99·05% with Hepatozoon sp. (OM033664) from the grey short-tailed opossum, M. domestica (Weck et al., Reference Weck, Serpa, Ramos, Luz, Costa, Ramirez, Benatti, Piovezan, Szabó, Marcili, Krawczak, Muñoz-Leal and Labruna2022). They also had 98·63–98·79% identity with Hepatozoon sp. (KM234615) from the house gecko, Hemidactylus mabouia (Moreau de Jonnés, 1818), and 98·71–98·86% identity with H. musa (KX880079) from P. nattereri (Harris et al., Reference Harris, Borges-Nojosa and Maia2015; Úngari et al., Reference Úngari, Netherlands, De Alcantara, Emmerich and Da Silva2021a). The genetic divergence between the 2 H. atrocis sp. nov. haplotypes and the other sequences ranged from 1 to 1·2% with Hepatozoon sp. (OM033664) from M. domestica, and 5–5·3% with Hepatozoon quagliattus Úngari, Netherlands, Silva and O’Dwyer, 2021 (MW591599) from the snake Dipsas mikanii Schlegel, 1837 (Úngari et al., Reference Úngari, Netherlands, De Alcantara, Emmerich and Da Silva2021a) (Table 3).

Table 3. The pairwise distance (p-distance) between the haplotype sequences of Hepatozoon atrocis sp. nov. from the present study with Hepatozoon spp. sequences obtained from a marsupial, tick and herpetofauna of Brazil (1397 bp)

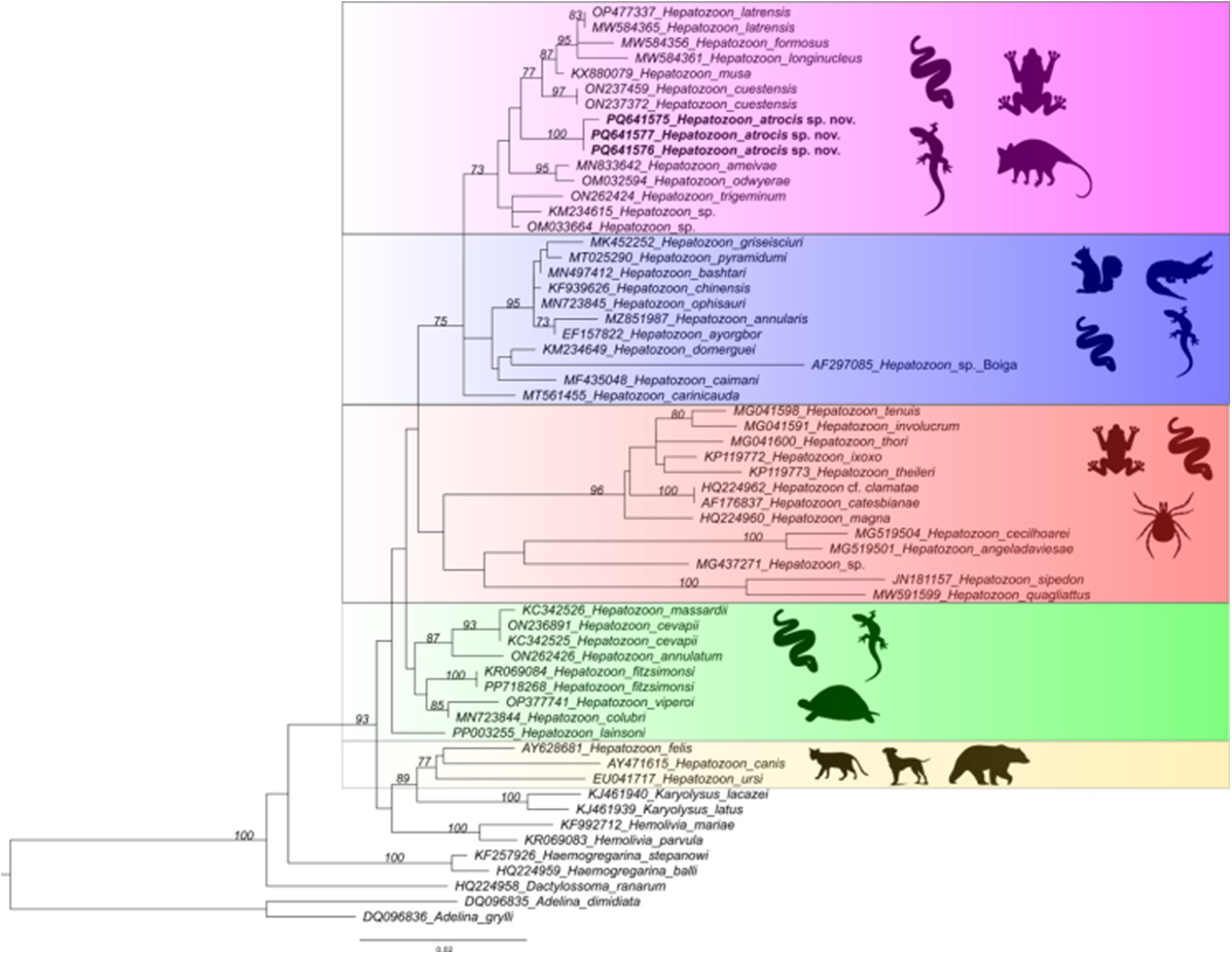

The ML phylogenetic analysis resulted in a tree of 1397 bp alignment (Figure 2). The phylogenetic analysis included isolates of haemogregarines (Haemogregarina, Hepatozoon, Karyolysus, Hemolivia and Dactylosoma), and coccidia (Adelina) as an outgroup. The topology showed that the new haplotype sequences of H. atrocis sp. nov. were recovered into a well-supported small clade (bootstrap: 100%) within a larger clade comprising Hepatozoon sequences derived from anurans, squamates and marsupials sampled in Brazil (Figure 2). The sequences obtained from other snake hosts that shared the same ancestor with H. atrocis sp. nov. were the following: H. cuestensis (ON237459 and ON237372) from Leptodeira annulata (Linnaeus, 1758) and B. moojeni, respectively; H. musa (KX880079) from P. nattereri; H. odwyerae (OM032594) from D. corais; and H. trigeminum (ON262424) from O. trigeminus (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Consensus phylogenetic tree using the maximum likelihood (ML) method, based on partial sequences of the 18S rRNA gene of Hepatozoon atrocis sp. nov. obtained in the present study (highlighted in bold) and sequences deposited in the GenBank database (1397 bp). Accession numbers are indicated in the sequences.

Discussion

To our knowledge, we presented the first description of a haemogregarine infecting a viperid snake from the Amazonia region. Viperidae is one of the most diverse snake families, comprising approximately 400 species distributed across Europe, Africa, Asia and the Americas, including oceanic islands (Alencar et al., Reference Alencar, Quental, Grazziotin, Alfaro, Martins, Venzon and Zaher2016). These venomous reptiles can be found in a wide range of ecosystems and are often abundant in their habitats (Maritz et al., Reference Maritz, Penner, Martins, Crnobrnja-Isailović, Spear, Alencar, Sigala-Rodriguez, Messenger, Clark, Soorae, Luiselli, Jenkins and Greene2016). Given such characteristics, viperids are compelling models for investigating Hepatozoon spp. diversity. The high diversity of species of Hepatozoon (n = 38) recorded in a small number of host species (n = 26) within the viperid taxon further supports the potential of viperids for such studies (see Table 1). On the other hand, these numbers also demonstrate our lack of knowledge about the parasitism of haemogregarines in this snake family – e.g., less than 10% of the viperid species have been reported as hosts for Hepatozoon spp. Besides that, there is a lack of molecular data for most of these described species to compare them in an accurate phylogenetic context.

Although the common lancehead snake is widely distributed in northern South America (Nogueira et al., Reference Nogueira, Argôlo, Arzamendia, Azevedo, Barbo, Bérnils, Bolochio, Borges-Martins, Brasil-Godinho, Braz, Buononato, Cisneros-Heredia, Colli, Costa, Franco, Giraudo, Gonzalez, Guedes, Hoogmoed, Marques, Montingelli, Passos, Prudente, Rivas, Sanchez, Serrano, Silva, Strüssmann, Vieira-Alencar, Zaher, Sawaya and Martins2019), Hepatozoon spp. have been detected in this host only in French Guiana and Brazil, albeit without species description (Thoisy et al., Reference Thoisy, Michel, Vogel and Vié2000; Kindlovits et al., Reference Kindlovits, Temoche, Machado and Almosny2017; Ogrzewalska et al., Reference Ogrzewalska, Machado, Rozental, Forneas, Cunha and De Lemos2019). Although there are records of three B. atrox snakes positive for Hepatozoon spp. in French Guiana, the authors provide neither morphological nor molecular data, thus making comparison impossible (Thoisy et al., Reference Thoisy, Michel, Vogel and Vié2000). In Brazil, Hepatozoon sp. DNA was detected in A. dissimile ticks collected from B. atrox, which was not investigated for haemoparasite infections (Ogrzewalska et al., Reference Ogrzewalska, Machado, Rozental, Forneas, Cunha and De Lemos2019). This sequence (MG437271) did not show identity to the sequences in our study and exhibited high similarity to Hepatozoon spp. detected in mammals and birds (98·2%) (Ogrzewalska et al., Reference Ogrzewalska, Machado, Rozental, Forneas, Cunha and De Lemos2019). Another study detected a haemogregarine similar to H. atrocis sp. nov. in one captive B. atrox in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (Kindlovits et al., Reference Kindlovits, Temoche, Machado and Almosny2017). Still, the absence of morphometric and molecular data prevents confirmation.

The parasitemia observed in blood smears of B. atrox can be considered relatively low for haemogregarines in snakes, which in extremely high infections can reach more than 60% of infected erythrocytes (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Shilton and Shine2006; Telford, Reference Telford2009). Data on parasitemia of Hepatozoon in viperids were recorded only in a few studies and ranged from 0·1% to 60% (Nadler and Miller, Reference Nadler and Miller1984; Peirce and Bengis, Reference Peirce and Bengis1998; Telford et al., Reference Telford, Butler and Telford2002; Morsy et al., Reference Morsy, Bashtar, Ghaffar, Al Quraishy, Al Hashimi, Al Ghamdi and Shazly2013; Úngari et al., Reference Úngari, Santos, O’Dwyer, Da Silva, Santos, Da Cunha and Cury2018, Reference Úngari, Netherlands, Santos, De Alcantara, Emmerich, Da Silva and O’Dwyer2022; Abdel-Baki et al., Reference Abdel-Baki, Mansour, Al-Malki, Al-Quraishy and Abdel-Haleem2020; Mansour et al., Reference Mansour, Abdel-Haleem, Al-Malki, Al-Quraishy and Abdel-Baki2020; Ceylan et al., Reference Ceylan, Úngari, Sönmez, Gul, Ceylan, Tosunoglu, Baycan, O’Dwyer and Sevinc2023). Low parasitemia may be related to the time of infection and/or the life stage of the host (Santos et al., Reference Santos, O’Dwyer and Silva2005; Brown et al., Reference Brown, Shilton and Shine2006). The B. atrox sampled here was an immature juvenile female, measuring 65·5 cm (snout-vent length) and weighing 80 g (Silva et al., Reference Silva, de Oliveira, De Souza Nascimento, Machado and Da Costa Prudente2017). In this case, the parasitemia might be explained by vertical transmission (Kauffman et al., Reference Kauffman, Sparkman, Bronikowski and Palacios2017), or due to predation of infected intermediate vertebrate hosts early in the juvenile stage (Smith, Reference Smith1996; Monteiro et al., Reference Monteiro, Contreras-Bernal, Bisneto, Sachett, Da Silva, Lacerda, Costa, Val, Brasileiro, Sartim, Silva-de-oliveira, Bernarde, Kaefer, Grazziotin, Wen and Moura-da-silva2020). Furthermore, snakes with recent infections up to eight weeks may present very low parasitemia ranging from 0·2% to 0·3% (Lowichik et al., Reference Lowichik, Lanners, Lowrie and Meiners1993; Telford, Reference Telford2009).

Morphological comparisons between H. atrocis sp. nov. and other Hepatozoon species infecting Bothrops spp. snakes revealed distinct characteristics (see Remarks). While some species exhibit similar gamont size ranges, the inability to accurately differentiate between mature and immature stages precludes precise comparisons (see Table 2). Moreover, morphometry may not be a reliable taxonomic criterion, as blood stages of haemogregarines can exhibit remarkable similarity, even among distinct species (Telford, Reference Telford2009). For instance, despite H. cuestensis, Hepatozoon cevapi (O’Dwyer et al., Reference O’Dwyer, Moço, Paduan, Spenassatto, Silva and Ribolla2013) and Hepatozoon massardii (O’Dwyer et al., Reference O’Dwyer, Moço, Paduan, Spenassatto, Silva and Ribolla2013) shared morphological features (e.g. elongated shapes) and comparable dimensions (17·07 ± 1·44 × 3·6 ± 0·55 µm, 17·05 ± 1·10 × 3·12 ± 0·49 µm and 17·31 ± 1·00 × 2·95 ± 0·38 µm; respectively), they represent different species (O’Dwyer et al., Reference O’Dwyer, Moço, Paduan, Spenassatto, Silva and Ribolla2013; Úngari et al., Reference Úngari, Netherlands, Santos, De Alcantara, Emmerich, Da Silva and O’Dwyer2022). Another example involves Hepatozoon catesbianae (Stebbins, 1904) and Hepatozoon clamatae (Stebbins, 1905), species with morphologically indistinguishable gamonts. Historically, these were differentiated based on cytopathological alterations seemingly specific to H. clamatae in anuran hosts. However, molecular data have since shown they are not distinct species (Léveillé et al., Reference Léveillé, Zeldenrust and Barta2021). Conversely, the same species may exhibit different morphometries, as seen with H. cevapii, which showed distinct morphometric variations in records made by its original authors (O’Dwyer et al., Reference O’Dwyer, Moço, Paduan, Spenassatto, Silva and Ribolla2013; Úngari et al., Reference Úngari, Netherlands, Santos, De Alcantara, Emmerich, Da Silva and O’Dwyer2022).

Only macromeronts (first-generation meronts) were observed, producing macromerozoites, which are larger and less numerous than the micromerozoites formed by micromeronts (second-generation meronts) (Telford, Reference Telford2009). The dizoic cyst represents latent stages, and it is typically found in the liver (Desser, Reference Desser and Kreier1993; Smith, Reference Smith1996), but was present in the B. atrox intestine. Its presence may indicate a role in transmission through predation of another B. atrox (Fraga et al., Reference Fraga, Lima, Prudente and Magnusson2013; Rodrigues et al., Reference Rodrigues, Maschio and Prudente2016). However, it is more likely that dizoic cysts provide a continuous infection for the snake, as they can eventually differentiate into meronts throughout infection (Desser, Reference Desser and Kreier1993; Telford, Reference Telford2009).

Regarding the genetic data, we observed a 0·2% p-distance between the H. atrocis sp. nov. 18S rRNA sequences, differing in two nucleotides. Notably, similar intraspecific sequence divergence is documented in other snake-associated Hepatozoon species. For instance, the two sequences of H. quagliattus showed 100% similarity and a 0·2% p-distance (Úngari et al., Reference Úngari, Netherlands, Santos, De Alcantara, Emmerich, Da Silva and O’Dwyer2022), and H. musa sequences with >99% similarity and a 0·2% p-distance (Úngari et al., Reference Úngari, Santos, O’Dwyer, Da Silva, Santos, Da Cunha and Cury2018). Conversely, although H. massardii and H. cevapii were initially described as distinct species based on a 0·2% divergence (O’Dwyer et al., Reference O’Dwyer, Moço, Paduan, Spenassatto, Silva and Ribolla2013; Úngari et al., Reference Úngari, Santos, O’Dwyer, Da Silva, Santos, Da Cunha and Cury2018), these two species shared >99% identity (Úngari et al., Reference Úngari, Santos, O’Dwyer, Da Silva, Santos, Da Cunha and Cury2018, Reference Úngari, Netherlands, Santos, De Alcantara, Emmerich, Da Silva and O’Dwyer2022) and were shown to be closely related and positioned within the same clade (Úngari et al., Reference Úngari, Santos, O’Dwyer, Da Silva, Santos, Da Cunha and Cury2018, Reference Úngari, Netherlands, Santos, De Alcantara, Emmerich, Da Silva and O’Dwyer2022). Even when comparing the short sequence of H. massardii (unique sequence) with the longer sequences of H. cevapii from studies conducted after its initial description (Úngari et al., Reference Úngari, Netherlands, Santos, De Alcantara, Emmerich, Da Silva and O’Dwyer2022). Furthermore, their morphological and morphometric characteristics are highly similar, with only minor variations in cytoplasm staining (O’Dwyer et al., Reference O’Dwyer, Moço, Paduan, Spenassatto, Silva and Ribolla2013). Gene mutations resulting from the cloning process can cause nucleotide polymorphisms and DNA divergence (Ferreira et al., Reference Ferreira, Perles, Machado, Prado and André2020). This was observed in haplotype sequences of Hepatozoon sp. from the anurans Leptodactylus latrans (Steffen, 1815) and Rhinella diptycha (Cope, 1862) (Ferreira et al., Reference Ferreira, Perles, Machado, Prado and André2020). A recent study on Hepatozoon caimani (Carini, 1909) from the caiman Caiman yacare (Daudin, 1801) identified distinct haplotypes with polymorphisms in several nucleotides and positioned them in subclades within the phylogeny (Clemente et al., Reference Clemente, Gutierrez-Liberato, Anjos, Simões, Mudrek, Fecchio, Lima, Oliveira, Pinho, Mathias, Guimarães and Kirchgatter2023). Despite this genetic variation, the authors did not consider it sufficient to determine new species designations, as all haplotypes maintained >99% identity with H. caimani (Clemente et al., Reference Clemente, Gutierrez-Liberato, Anjos, Simões, Mudrek, Fecchio, Lima, Oliveira, Pinho, Mathias, Guimarães and Kirchgatter2023). Similarly, the observed divergence in the cloned sequences of H. atrocis sp. nov. likely represents intraspecific haplotype variation (H1 and H2) within the same host species rather than distinct species.

Overall, the recovered phylogeny presented herein showed the known paraphyletic pattern of the genus, with the organization of two major distinct clades separating Hepatozoon of carnivores from other species (Karadjian et al., Reference Karadjian, Chavatte and Landau2015; Zechmeisterová et al., Reference Zechmeisterová, Javanbakht, Kvicerová and Siroký2021; Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Santodomingo, Saboya-Acosta, Quintero-Galvis, Moreno, Uribe and Muñoz-Leal2024). It also maintained the phylogenetic relationships of Hepatozoon spp. from Brazilian snakes, which were distributed into four main clades (Paula et al., Reference Paula, Picelli, Perles, André and Viana2022; Úngari et al., Reference Úngari, Netherlands, Santos, De Alcantara, Emmerich, Da Silva and O’Dwyer2022; Picelli et al., Reference Picelli, Silva, Correa, Paiva, Paula, Hernández-Ruz, Oliveira and Viana2023). The 18S rRNA haplotypes of H. atrocis sp. nov. clustered in one of these clades, forming a sister taxon of two subclades composed of Hepatozoon lineages from different vertebrate groups (i.e. anurans, squamates and marsupial) mainly from the Brazilian Cerrado biome (Úngari et al., Reference Úngari, Netherlands, Santos, De Alcantara, Emmerich, Da Silva and O’Dwyer2021b, Reference Úngari, Netherlands, Santos, De Alcantara, Emmerich, Da Silva and O’Dwyer2022). This relationship between Hepatozoon species in herpetofauna and small mammals is well-established, as evidenced by phylogenetic studies on this parasite genus (Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Santodomingo, Saboya-Acosta, Quintero-Galvis, Moreno, Uribe and Muñoz-Leal2024). The proximity of H. atrocis sp. nov. with Hepatozoon species of anurans and the grey short-tailed opossum indicates a potential use of the same vector group by these parasites. Considering that several tick species that parasitize B. atrox snakes can also be found in anurans (Mendoza-Roldan et al., Reference Mendoza-Roldan, Ribeiro, Castilho-Onofrio, Grazziotin, Rocha, Ferreto-Fiorillo, Pereira, Benelli, Otranto and Barros-Battesti2020) and small mammals (Guglielmone and Nava, Reference Guglielmone and Nava2010), the role of ticks as vectors of Hepatozoon across this clade should be further investigated (Mendoza-Roldan et al., Reference Mendoza-Roldan, Ribeiro, Castilho-Onofrio, Marcili, Simonato, Latrofa, Benelli, Otranto and Barros-Battesti2021). Additionally, such phylogenetic relationships could be explained by the transmission of Hepatozoon via the food web (Sloboda et al., Reference Sloboda, Kamler, Bulantová, Votýpka and Modrý2008; Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Santodomingo, Saboya-Acosta, Quintero-Galvis, Moreno, Uribe and Muñoz-Leal2024). The detection of Hepatozoon sp. in lung and spleen samples of M. domestica might indicate that this marsupial species may have a role as a paratenic host for snake-associated Hepatozoon spp. (Carvalho et al., Reference Carvalho, Passos and Lessa2019; Weck et al., Reference Weck, Serpa, Ramos, Luz, Costa, Ramirez, Benatti, Piovezan, Szabó, Marcili, Krawczak, Muñoz-Leal and Labruna2022; Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Santodomingo, Saboya-Acosta, Quintero-Galvis, Moreno, Uribe and Muñoz-Leal2024). Furthermore, despite being considered a generalist species, B. atrox has ontogenetic shifts in diet and microhabitat use (Bisneto and Kaefer, Reference Bisneto and Kaefer2019; Monteiro et al., Reference Monteiro, Contreras-Bernal, Bisneto, Sachett, Da Silva, Lacerda, Costa, Val, Brasileiro, Sartim, Silva-de-oliveira, Bernarde, Kaefer, Grazziotin, Wen and Moura-da-silva2020). While juveniles commonly occupy higher strata in the vegetation and have a diet consisting of ectothermic animals (e.g. fish, frogs, lizards and snakes), adults are typically found on the ground and prey on endothermic animals (e.g. small mammals and birds) (Monteiro et al., Reference Monteiro, Contreras-Bernal, Bisneto, Sachett, Da Silva, Lacerda, Costa, Val, Brasileiro, Sartim, Silva-de-oliveira, Bernarde, Kaefer, Grazziotin, Wen and Moura-da-silva2020), including marsupials (Voss, Reference Voss2013).

Our phylogenetic results demonstrate that Hepatozoon parasites of viperids have different evolutionary origins, which are not necessarily related to host taxonomy or geographic distribution. The lineages described in Brazilian viperid snakes were positioned in four distinct clades. The new small clade contained sequences of H. atrocis sp. nov. that clustered closely with the H. cuestensis clade and related to this last one the clade of H. musa. Another distinct group contained H. cevapii and H. massardii, which were distant from all the other lineages. The relationships among H. cuestensis, H. cevapii, H. massardii and H. musa remained consistent with previous studies (O’Dwyer et al., Reference O’Dwyer, Moço, Paduan, Spenassatto, Silva and Ribolla2013; Úngari et al., Reference Úngari, Santos, O’Dwyer, Da Silva, Santos, Da Cunha and Cury2018). This pattern was also observed in Saudi Arabian viperid species, Hepatozoon bashtari (Abdel-Baki et al., Reference Abdel-Baki, Mansour, Al-Malki, Al-Quraishy and Abdel-Haleem2020) of Echis coloratus Günther, 1878 (Abdel-Baki et al., Reference Abdel-Baki, Mansour, Al-Malki, Al-Quraishy and Abdel-Haleem2020) and Hepatozoon pyramidumi (Mansour et al., Reference Mansour, Abdel-Haleem, Al-Malki, Al-Quraishy and Abdel-Baki2020) of Echis pyramidum (Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, 1827) (Mansour et al., Reference Mansour, Abdel-Haleem, Al-Malki, Al-Quraishy and Abdel-Baki2020), which formed a distinct clade separate from other viperid species. Similarly, Hepatozoon viperoi (Ceylan et al., Reference Ceylan, Úngari, Sönmez, Gul, Ceylan, Tosunoglu, Baycan, O’Dwyer and Sevinc2023) from Vipera ammodytes (Linnaeus, 1758) from Türkiye (Ceylan et al., Reference Ceylan, Úngari, Sönmez, Gul, Ceylan, Tosunoglu, Baycan, O’Dwyer and Sevinc2023) also grouped distinctly but closely with H. cevapii and H. massardii from Brazil (O’Dwyer et al., Reference O’Dwyer, Moço, Paduan, Spenassatto, Silva and Ribolla2013).

The proximity of H. atrocis sp. nov. and H. cuestensis may be explained by the shared life history of their hosts. Indeed, the H. cuestensis sequence was the only one, so far, obtained from another snake species of the genus Bothrops, B. moojeni (Úngari et al., Reference Úngari, Netherlands, Santos, De Alcantara, Emmerich, Da Silva and O’Dwyer2022). Both B. moojeni and B. atrox are generalist predators that consume a similar range of prey, including rodents, amphibians and lizards (Nogueira et al., Reference Nogueira, Sawaya and Martins2003). While B. moojeni is primarily found in the Cerrado and Pantanal biomes and does not overlap with B. atrox in our study region, these species can co-occur in some areas of Brazil (Nogueira et al., Reference Nogueira, Argôlo, Arzamendia, Azevedo, Barbo, Bérnils, Bolochio, Borges-Martins, Brasil-Godinho, Braz, Buononato, Cisneros-Heredia, Colli, Costa, Franco, Giraudo, Gonzalez, Guedes, Hoogmoed, Marques, Montingelli, Passos, Prudente, Rivas, Sanchez, Serrano, Silva, Strüssmann, Vieira-Alencar, Zaher, Sawaya and Martins2019; Costa et al., Reference Costa, Guedes and Bérnils2022). Thus, exposure to similar arthropod vectors or shared paratenic hosts due to overlapping ecological niches potentially facilitates the transmission of closely related Hepatozoon species.

A broader understanding of the relationships in the evolutionary history of Hepatozoon in viperid species, as well as other heteroxenous parasites, requires data on other components of their life cycle, such as the vectors (Barta et al., Reference Barta, Ogedengbe, Martin and Smith2012; Votýpka et al., Reference Votýpka, Modrý, Oborník, Slapeta, Lukes, Archibald, Simpson and Slamovits2017). The natural life cycle of Hepatozoon in viperid snakes has not been elucidated, but through experimental infections with laboratory-reared mosquitoes, it was possible to verify the sporogonic development of at least 8 species – Hepatozoon horridus (Telford et al., Reference Telford, Moler and Butler2008), Hepatozoon mehlhorni (Bashtar et al., Reference Bashtar, Abdel-Ghaffar and Shazly1991), Hepatozoon moccassini (Laveran, Reference Laveran1902), H. plimmeri, H. roueli, Hepatozoon seurati (Laveran and Pettit, Reference Laveran and Pettit1911) Hepatozoon sauritus (Telford et al., Reference Telford, Wozniak and Butler2001) and Hepatozoon sistruri (Telford et al., Reference Telford, Butler and Telford2002) – indicating mosquitoes as possible vectors for these parasites (Pessôa et al., Reference Pessôa, Belluomini, De Biasi and De Souza1971; Pessôa and De Biasi, Reference Pessôa and De Biasi1972; Nadler and Miller, Reference Nadler and Miller1984; Abdel-Ghaffar et al., Reference Abdel-Ghaffar, Bashtar and Shazly1991; Bashtar et al., Reference Bashtar, Abdel-Ghaffar and Shazly1991; Telford et al., (Reference Telford, Butler and Telford2002); Telford et al., Reference Telford, Moler and Butler2008; Morsy et al., Reference Morsy, Bashtar, Ghaffar, Al Quraishy, Al Hashimi, Al Ghamdi and Shazly2013).

In summary, morphological and morphometric characterization revealed blood and tissue stages of a haemogregarine in the common lancehead snake (B. atrox), which is distinct from previously described species. Molecular evidence supported the identification of a new species, namely H. atrocis sp. nov. This new record not only expands the geographic distribution of haemogregarines in viperids within Brazil but also provides the first genetic record of this parasite in an Amazonian viperid. In conjunction with an updated checklist of Hepatozoon spp. in viperids, this study offers a comprehensive view of Hepatozoon parasitism within this snake family, showing that this interaction is still underestimated, especially in the Amazonia region.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182025101388.

Data availability statement

Sequence data are available at GenBank accessions: PQ641575, PQ641576 and PQ641577 (partial 18S rRNA). The snake specimen voucher was deposited at the Laboratório de Herpetologia of Universidade Federal do Amapá (no 4010). Parasite hapantotypes (COLPROT 1019) were deposited in the Coleção de Protozoários – COLPROT, Fundação Oswaldo Cruz – Fiocruz, Brazil.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Laboratory of Morphophysiological and Parasitic Studies of the Federal University of Amapá for providing a microscope, materials and workspace; the Vector-Borne Bioagents Laboratory of the São Paulo State University for DNA extraction, PCR, cloning and sequencing; and Pedro F. Bisneto for the photographic image of the snake B. atrox used in the graphical summary.

Author contributions

F.R.d.P., A.M.P., L.A.V. and F.A.C.P. conceived and designed the study. F.R.d.P. performed the fieldwork and microscopic analysis. A.C.C. and M.R.A. performed the molecular analysis. G.d.S.C. performed the phylogenetic analysis. A.M.P. and F.R.d.P. processed the data, interpreted the results and worked on the manuscript. L.A.V. and F.A.C.P. were responsible for funding acquisition, supervision and project administration. All authors participated in the preparation, reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Financial support

This study was financed in part by the Brazilian Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES Finance Code 001) and supported by the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq Universal 429.132/2016-6 to L.A.V). F.A.C.P. and M.R.A. (Process #303701/2021-8) thank CNPq for the productivity scholarship. A.M.P. is grateful to the National Science Foundation (NSF) (grant NSF 2146654) and CNPq (PDJ 150357/2025-7) for the postdoctoral fellowship. F.R.d.P. would like to thank the Brazilian CAPES (Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel) for the doctoral scholarship.

Competing interests

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical standards

All procedures performed in this study involving animals were approved by the ethics committee on animal use from UNIFAP (protocol number 02/2020), and snake sampling and access to the genetic data were authorized by the Brazilian Ministry of the Environment (SISBIO number 838922 and SISGEN AB23235, respectively).