Introduction

Fasciolosis is a food-borne zoonotic disease caused by Fasciola gigantica and Fasciola hepatica, and in Bangladesh, F. gigantica, but not F. hepatica, is highly prevalent. Fasciolosis has been recognized as a neglected tropical disease (NTD), and over 180 million people in 75 countries are infected (Anisuzzaman et al. Reference Anisuzzaman, Hossain, Hatta, Labony, Kwofie, Kawada, Tsuji, Alim, Rollinson and Stothard2023; Liu et al. Reference Liu, Lu, Yang, Qian, Yang, Tan and Zhou2024). Globally, over 600 million animals are at risk of infection with Fasciola. Although Fasciola spp. have wide host range, including sheep, cattle, goats, buffaloes, camelids, cervids (deer), equids, lagomorphs (rabbits and hares), macropods/marsupials (e.g., kangaroos, wallabies, tree-kangaroos, wallaroos, pademelons, quokkas) and rodents; however, the flukes are more common in ruminants (e.g., sheep, goats and cattle) (Tanabe et al. Reference Tanabe, Caravedo, Clinton White and Cabada2024) . In ruminants, liver flukes cause severe liver damage, such as calcification of the bile ducts and liver atrophy in cattle, but swollen liver along with the formation of an abscess-like cavity containing adult flukes, soft choleliths and fetid fluid in goats (Anisuzzaman et al. Reference Anisuzzaman, Hossain, Hatta, Labony, Kwofie, Kawada, Tsuji, Alim, Rollinson and Stothard2023; Ali et al., Reference Ali, Labony, Hossain, Alam, Khan, Alim and Anisuzzaman2024, Reference Ali, Hossain, Labony, Dey, Paul, Khan, Alim and Anisuzzaman2025), leading to hypoproteinemia, edema and bottle jaw (Elelu and Eisler, Reference Elelu and Eisler2018). Fascioliosis can cause annual financial losses of over US$3 billion (Kipyegen et al. Reference Kipyegen, Muleke and Otachi2022; Ali et al. Reference Ali, Hossain, Labony, Dey, Paul, Khan, Alim and Anisuzzaman2025). The prevalence of fascioliosis ranges from 30% to 90% in ruminants in different countries (Khan et al. Reference Khan, Sajid, Riaz, Ahmad, He, Shahzad, Hussain, Khan, Iqbal and Zhao2013; Yasin et al. Reference Yasin, Alim, Anisuzzaman, Ahasan, Munsi, Chowdhury, Hatta, Tsuji and Mondal2018; Ali et al. Reference Ali, Hossain, Labony, Dey, Paul, Khan, Alim and Anisuzzaman2025). In Bangladesh, the disease is extremely common in livestock, and the prevalence ranges up to >76% (Rahman et al. Reference Rahman, Islam, Talukder, Hassan, Dhand and Ward2017; Yasin et al. Reference Yasin, Alim, Anisuzzaman, Ahasan, Munsi, Chowdhury, Hatta, Tsuji and Mondal2018).

Various freshwater snails, such as Lymnaea auricularia, Lymnanea luteola, Lymnaea truncatula, Lymnaea cousin, Lymnaea cubensis, Lymnaea diaphana, Lymnaea humilis, Lymnaea neotropica, Lymnaea occulta, Lymnaea stagnalis, Lymnaea viatrix, Omphiscola glabra, Pseudosuccinea columella, Stagnicola caperata, Stagnicola fuscus, Stagnicola palustris, Stagnicola turricula, Radix lagotis, Radix natalensis, Radix peregra and Radix rubiginosa act as intermediate host of Fasciola spp. globally (Vázquez et al. Reference Vázquez, Alda, Lounnas, Sabourin, Alba, Pointier and Hurtrez-Boussès2019). Based on morphological features, L. auricularia and L. luteola have been reported to act as intermediate hosts of Fasciola spp. in Bangladesh (Ali et al. Reference Ali, Hossain, Labony, Dey, Paul, Khan, Alim and Anisuzzaman2025).

On the other hand, schistosomiasis is a snail-borne trematode infection with a broad host range, including cattle, sheep, goats, buffaloes, pigs, horses, canids, felids, humans and birds (Labony et al. Reference Labony, Hossain, Hatta, Dey, Mohanta, Islam, Shahiduzzaman, Hasan, Alim, Tsuji and Anisuzzaman2022). Also, globally it affects >250 million people (Anisuzzaman et al. Reference Anisuzzaman, Frahm, Prodjinotho, Bhattacharjee, Verschoor and Da Prazeres Costa2021, Reference Anisuzzaman, Hossain, Hatta, Labony, Kwofie, Kawada, Tsuji, Alim, Rollinson and Stothard2023). Schistosomatidae consists of >130 species and 17 genera. However, in Bangladesh, the existence of Schistosoma indicum, S. incognitum, S. nasale, S. spindale and Trichobilharzia szidati has been confirmed (Labony et al. Reference Labony, Hossain, Hatta, Dey, Mohanta, Islam, Shahiduzzaman, Hasan, Alim, Tsuji and Anisuzzaman2022), and S. spindale and S. indicum have been reported to cause intestinal schistosomiasis in ruminants (Attwood, Reference Attwood2010). In addition, cercariae of some non-human schistosomes induce swimmer’s itch (Horák et al. Reference Horák, Mikeš, Lichtenbergová, Skála, Soldánová and Brant2015). In the country, swimmer’s itch is a big problem, particularly for the farmers and fishermen (Labony et al. Reference Labony, Hossain, Hatta, Dey, Mohanta, Islam, Shahiduzzaman, Hasan, Alim, Tsuji and Anisuzzaman2022). Based on the morphometrical analysis, L. luteola, L. auricularia, Physa acuta, Indoplarbis exustus and Vibiparus bengalensis have been predicted to play a role as intermediate host of schistosomes in Bangladesh (Labony et al. Reference Labony, Hossain, Hatta, Dey, Mohanta, Islam, Shahiduzzaman, Hasan, Alim, Tsuji and Anisuzzaman2022). Bangladesh is crisscrossed by many natural and man-made water bodies where snails are abundant. Irrigation canals also serve as an ideal habitat for snails (Anisuzzaman et al. Reference Anisuzzaman, Alim, Rahman and Mondal2005). However, the species of snails that act as intermediate hosts for liver flukes and schistosomes have yet to be confirmed. Here, we identify different snails from different water bodies and validate their species using multiple molecular and bioinformatic tools.

Materials and methods

Snail collection and recording data

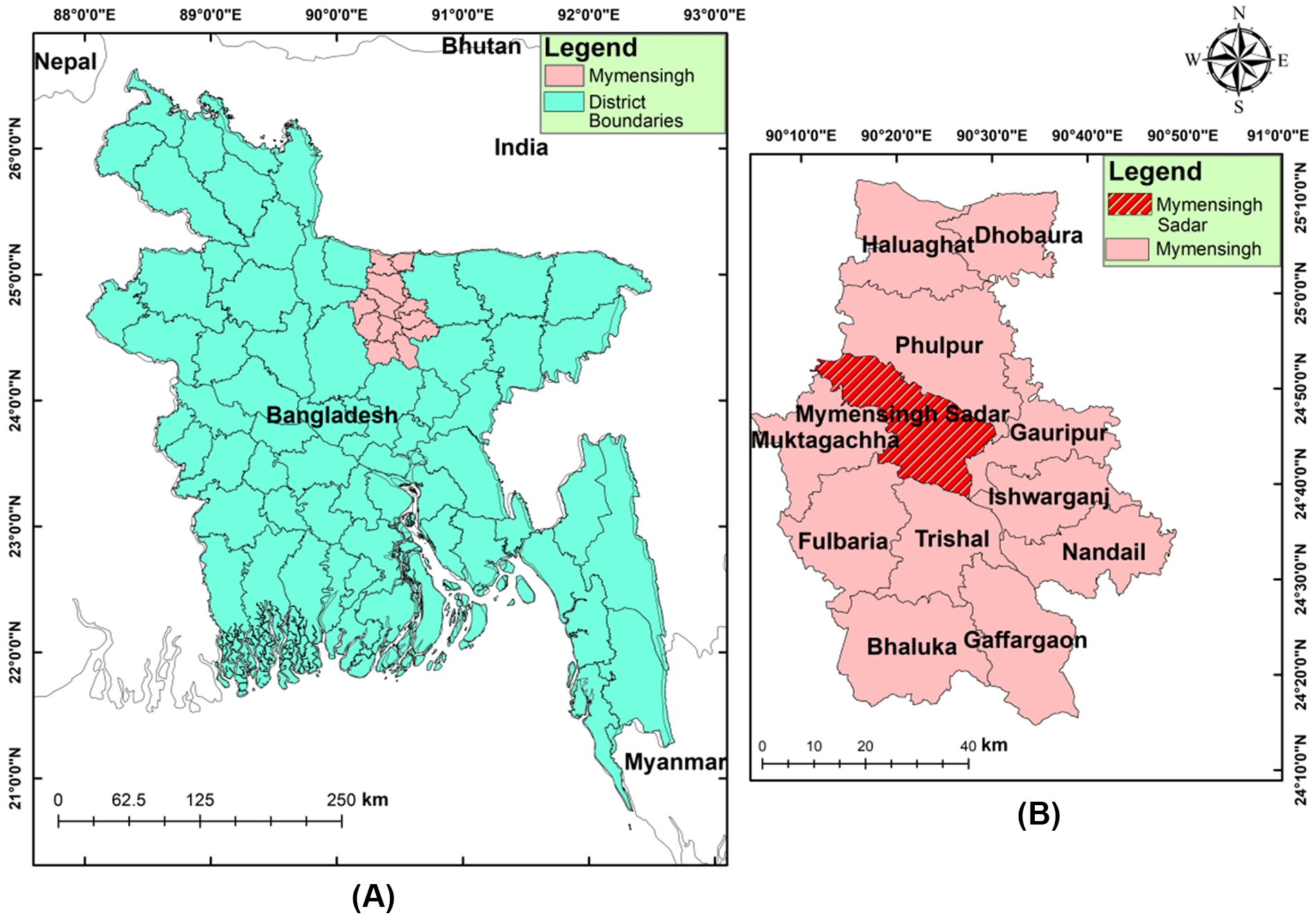

The study was conducted at Mymensingh Sadar (Figure 1) areas located in Mymensingh district. The study was carried out from January 2022 to December 2024. Information was recorded on a predesigned form which included (1) general information (water body name, type, nearby village); (2) water properties data (water flow, water level and depth); (3) ecological data (vegetation, animal contact and human contact); and (4) snail data (snail species and abundance). Snails were collected manually or using large scoops.

Figure 1. Map showing the study area. (A) Map of Bangladesh highlighting Mymensingh district. (B) District map of Mymensingh showing study areas (red highlighted).

Morphological and morphometrical identification of snail species

After washing, snails were placed in a petri dish and examined by close inspection; in some cases, examination was aided by a magnifying glass. Snails were identified by their shell characteristics (Malek and Cheng, Reference Malek and Cheng1974). Remarkable shell characteristics such as (1) shape of the shell, (2) presence or absence of the aperture, (3) apex, (4) suture, (5) presence or absence of the costa and tubercles and (6) sculpture were considered. For morphometrical analysis, height (length of the shell from the upper border of the aperture to the apex of the shell) and width (at the middle of the body whorl) were measured using a scale. The length and width of at least 100 shells of each species of different sizes were measured. Then the average height and width were calculated.

Checking for cercarial shedding

After tentative identifications, snails were examined for shedding of cercariae by exposing them to a lamp (6000 lux) or sunlight (on sunny days) for 3 h as described previously (Maeda et al. Reference Maeda, Hatta, Tsubokawa, Mikami, Nishimaki, Nakamura, Anisuzzaman, Matsubayashi, Ogawa, Da Costa and Tsuji2018; Frahm et al. Reference Frahm, Anisuzzaman, Prodjinotho, Vejzagić, Verschoor and Da Prazeres Costa2019). Aggressed cercariae were examined under a microscope and identified by morphological features described previously (Labony et al. Reference Labony, Hossain, Hatta, Dey, Mohanta, Islam, Shahiduzzaman, Hasan, Alim, Tsuji and Anisuzzaman2022). The snails that did not shed the cercariae were crushed by a pestle and mortar, and the hemolymph was examined under a dissecting microscope (10×) for the detection of developmental stages of the flukes.

Sample collection from snails and genomic DNA (gDNA) extraction

The snail samples were selected from each tentatively identified snail. Approximately 50 mg of tissue from the foot-pad region of each snail was collected, preserved in absolute (100%) ethanol, and stored at −20 °C. Before use, preserved samples were thawed at room temperature and centrifuged at 1200 ×g for 5 min. The supernatant alcohol was discarded. Then the specimens were placed in TAE buffer (10 mM Tris, 0.1 mM EDTA), pH 7.4, for 1 h to remove any residual alcohol from the tissues, since traces of alcohol can interfere with subsequent gDNA extraction. The collected tissues from each snail were grinded with a sterile pestle and mortar separately, and sonicated. The gDNA was extracted using QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germany) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, the sonicated tissues were lysed with lysis buffer loaded into an extraction column and centrifuged at 8000 ×g for 1 min. The column was then washed extensively with wash buffer, and the entrapped gDNA was eluted with 80 μL of elution buffer. The concentration of gDNA was measured using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer. In addition, gDNA was also extracted from tentatively identified cercariae.

Amplification of the gDNA of snails and cercariae

The mitochondrial cyclooxygenase 1 (Cox1) gene of gastropod snails was amplified using the primers (LCO1490: 5′-GGT CAA CAA ATC ATA AAG ATA TTG G-3′ and HCO2198: 5′-TAA ACT TCA GGG TGA CCA AAA AAT CA-3′). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) conditions for the Cox1 gene were 94 °C for 4 min followed by 35 cycles of 1 min each of 94 °C, 50 °C and 72 °C, with final extension at 72 °C for 8 min (Saijuntha et al. Reference Saijuntha, Tantrawatpan, Agatsuma, Rajapakse, Karunathilake, Pilap, Tawong, Petney and Andrews2021). In addition, for the confirmation of schistosome cercariae, which is known as furcocercus cercariae (FC), a fragment of the 28S rRNA gene was amplified using a primer set (forward: 5′-CTG AGC TAC CCT TGG AGT CG-3′ and reverse: 5′-CAC TGA CAA GCA GAC CCT CA-3′) following procedures as described elsewhere (Labony et al. Reference Labony, Hossain, Hatta, Dey, Mohanta, Islam, Shahiduzzaman, Hasan, Alim, Tsuji and Anisuzzaman2022). Also, internal transcribed spacer (ITS1)‐based PCR was conducted for the confirmation of fasciolid cercariae, which are also known as gymnocephalus cercariae (GC) (Ali et al. Reference Ali, Labony, Hossain, Alam, Khan, Alim and Anisuzzaman2024). Then, each PCR product was mixed with DNA loading dye and loaded into an agarose gel (1.5%) impregnated with Midori Green Advance. The gel was electrophoresed for 30 min at 100 volts. Then the gel was visualized in ultraviolet light.

Purification of PCR product and sequencing

PCR products were purified by gel extraction using a NucleoSpin Gel and PCR clean-up kit (Macherey − Nagel, Düren, Germany). The purified PCR products were subjected to sequencing in both directions with the same primers used for PCR amplification and a BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems) on an ABI3500 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). The resulting sequences were initially assembled using BioEdit 7.2 (https://bioedit.software.informer.com/7.2/) software. Obtained sequences were deposited in GenBank using the accession numbers (GenBank accession numbers: PV451212, PV451602-PV451603, PV451613, PV451617–PV451618, PV459747–PV459749 and PV460713–PV460715).

Bioinformatics analysis of the query sequences and building a phylogenetic tree

Cox1 orthologues were identified using BLAST® (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi), and sequences with higher identity (∼98%) were chosen and collected from GenBank (NCBI). Sequences were aligned using CLUSTALW (https://www.genome.jp/tools-bin/clustalw) for pair-wise comparisons with previously published sequences. Phylogenetic analysis was performed using neighbor joining (NJ), maximum likelihood (ML) and minimum parsimony (MP) methods, based on the Tamura-Nei model. Confidence limits were assessed using the bootstrap procedure (1000 replicates) for NJ, ML and MP trees, and other settings were obtained using the default values in MEGA v11 (Tamura et al. Reference Tamura, Stecher and Kumar2021). A 50% cutoff value was implemented for the consensus tree.

Statistical analysis

The generated data were plotted onto a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. Descriptive statistics were employed for the analysis of the data. Epidemiological data were analysed using a Z test. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Freshwater snails morphologically identified from Bangladesh

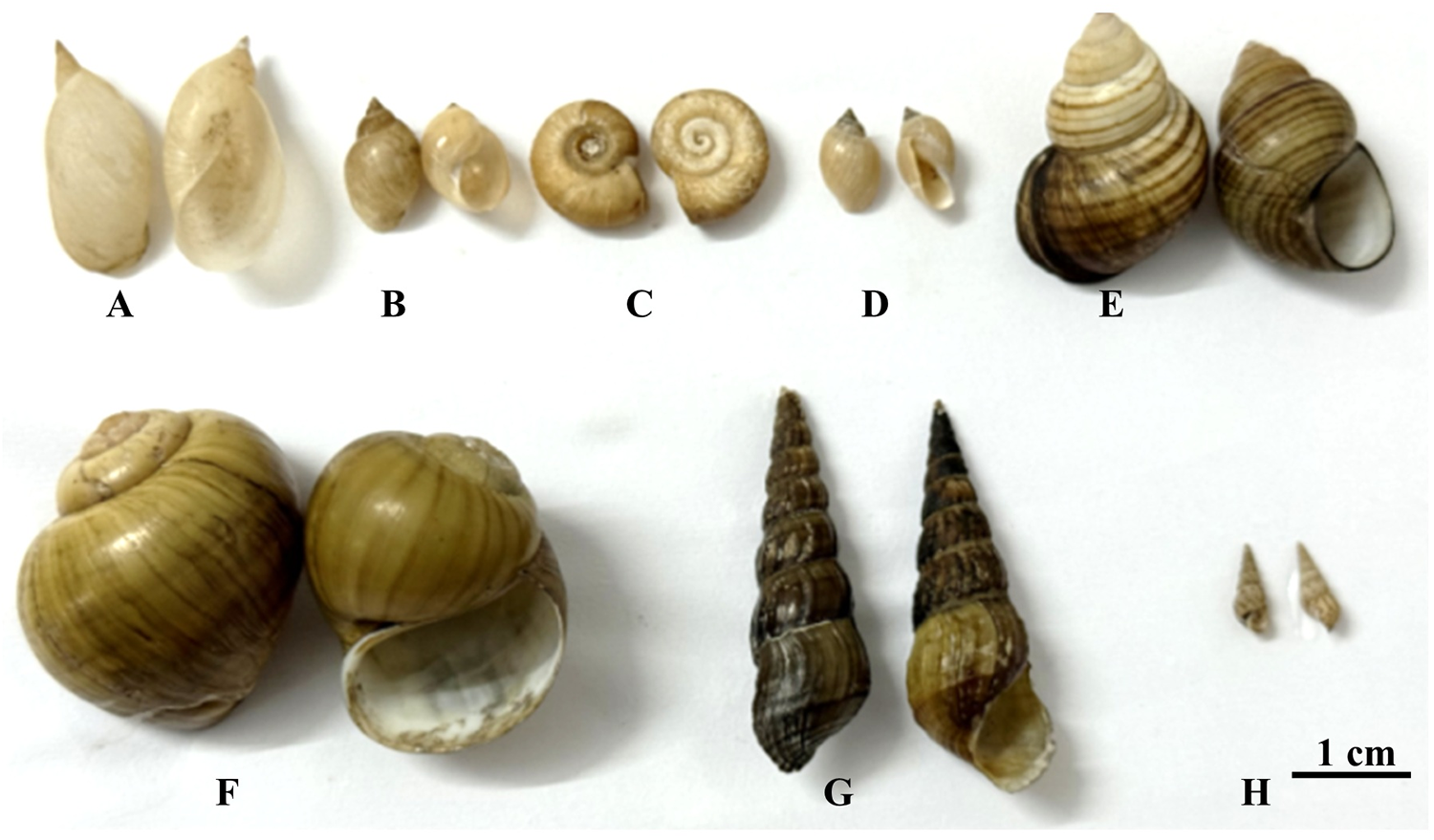

Snails of different species, namely, L. luteola, L. auricularia, Indoplanorbis exustus, P. acuta, V. bengalensis, Brotia spp., Pila globosa, Bithynea spp. and Thiara spp. were collected and examined for their morphological and morphometrical identification (Figure 2). Detailed morphological and morphometrical features have been presented in the Table 1.

Figure 2. Snails identified from the study areas. (A) Lymnaea auricularia, (B) L. Luteola, (C) Indoplanorbis exustus, (D) Physa acuta, (E) Viviparus bengalensis, (F) Pila globosa, (G) Brotia spp. and (H) Thiara spp.

Table 1. Morphological and morphometrical features and land marks of shells of the studied snails

Ecology of the snails examined

All the identified snails were collected from different natural and man-made water bodies. Lymnaeid snails were common in paddy fields and beels. However, they were more common in paddy fields with slightly free-flowing, clear and shallow water. L. auricularia was more common in the beels. Lymnaeid snails were frequently found attached to aquatic vegetation. Planorbids snails were commonly found in rivers, beels and paddy fields with clear, flowing water. In most cases, planorbid snails were frequently found attached to the roots of water hyacinths. Thiara and Brotia were commonly seen in rivers with slow water current. They were frequently found in the periphery of rivers, particularly during dry seasons when the river depth became shallow. Brotia spp. were also found in the ponds. V. bengalensis and P. globose were the most abundant species of fresh water snails found in Bangladesh. They had vast aquatic habitats, including drains, canals, rivers, paddy fields, beels and marshy areas. Both species were prevalent in the rainy seasons. On the other hand, P. acuta was abundant in paddy fields, drains and beels with muddy water (Figure 3A,B,C,D).

Figure 3. Habitats of snails. (A) Marshy areas, (B) Drain, (C) Paddy field and (D) Canal.

The intermediate host of Fasciola spp

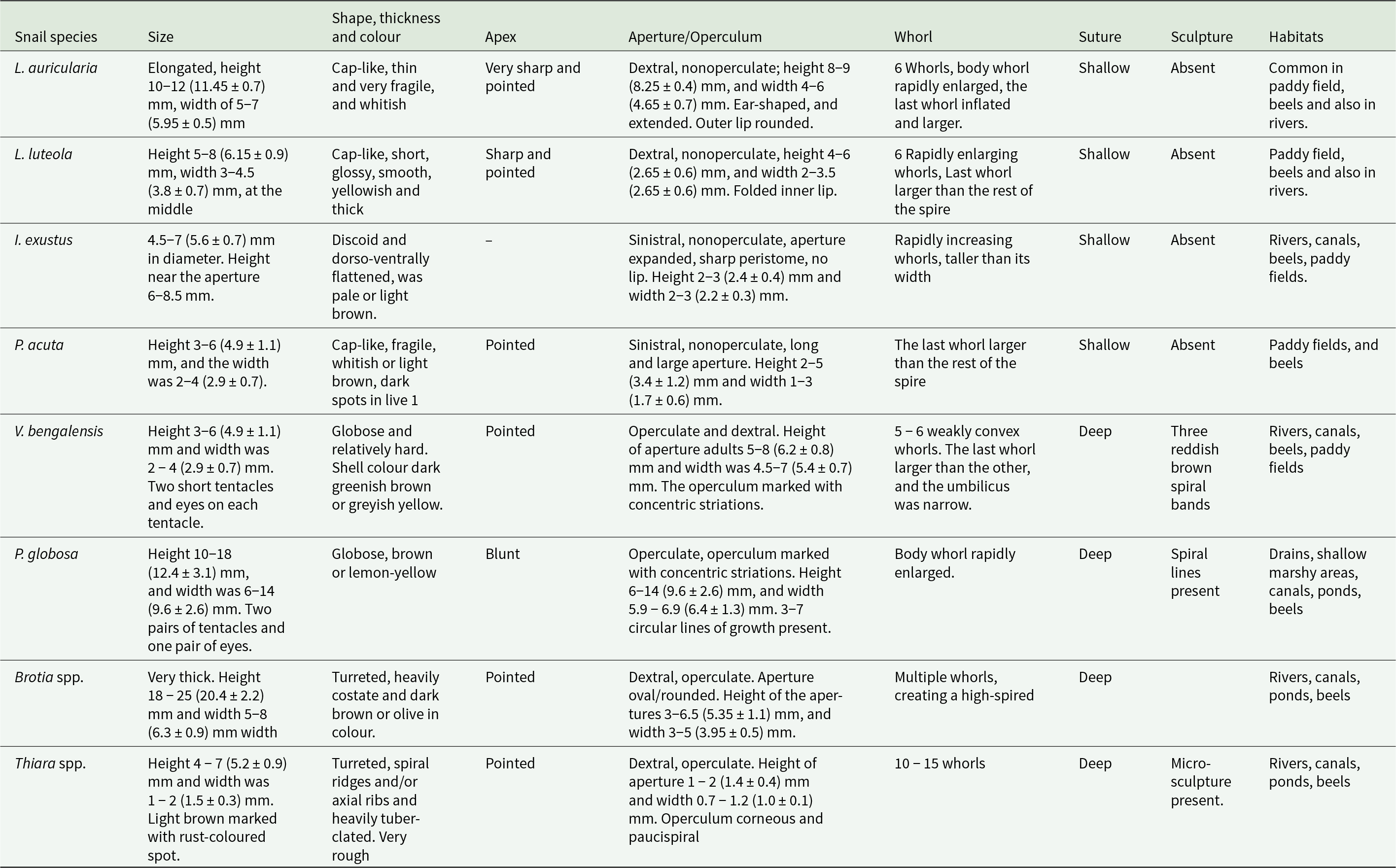

Of the studied snails, only L. auricularia and L. luteola released GC. Cercariae of Fasciola were characterised by a small, ovoid body about 250–300 µm long, covered with a thin tegument and sensory papillae. They had a long, unbranched tail, roughly twice the length of the body. During microscopic examination, by adding a drop of iodine, GCs were found to have an oral sucker at the anterior end and a small ventral sucker close to the oral sucker. They had a simple digestive system, including a pharynx and intestine extending from the body (Figure 4B). Using gDNA from GCs, we conducted ITS1-based PCR, and obtained an amplicon at the expected level (680 bp), confirming the release of fasciolid cercariae by the snails (Supplementary Figure 1). The study detected GCs only from 0.72% (7 out of 977) L. auricularia and 0.36% (8 out of 2240) L. luteola snails examined. GCs were not detected in other snails examined.

Figure 4. Cercariae identified from fresh water snails. (A) Gymnocephalus cercariae (GC) of Fasciola spp. (B) Furcocercus cercariae (FC)/scistosome cercariae (SC). OS, oral sucker; VS, ventral sucker.

Intermediate host of Schistosoma spp

In the present study, FC were detected in 5 species of snails, such as I. exustus, L. auricularia, L. luteola, P. acuta and V. bengalensis, but not in Brotia spp., Thiara spp. and P. globosa. FC were identified by their distinct morphology, including a bifurcated tail resembling a ‘tuning fork’, called a furca (Figure 4B), and a rounded head containing digestive and sensory structures essential for host-seeking behaviour. Using gDNA from FC, we conducted 28s rRNA gene-based PCR and we got amplicon at the expected level (340 bp), confirming the release of schistosomatid cercariae by the snails (Supplementary Figure 2). The study found that the highest prevalence of FC was in L. luteola (10.1%, 226 out of 2240) followed by that in L. auricularia (9.42%, 92 out of 977), I. exustus (5.43%, 19 out of 350), P. acuta (2.4%, 11 out of 450) and V. bengalensis (0.14%, 7 out of 500). Interestingly, we did not detect simultaneous shedding of both FC and GC by the same snail.

Identification of species of vector snails by PCR coupled with sequencing and bioinformatics

After morphological and morphometrical identifications of snails, the species of only fasciolid and schistosomatid vector snails were confirmed by PCR coupled with sequencing and bioinformatics analysis. To do this, the Cox 1 gene was amplified using a global primer that can amplify all mollusks, including freshwater snails. The conducted PCR was successful, and amplicons were detected at the expected level (∼750 bp) (Supplementary Figure 3). Since the study used a global primer, PCR could not confirm the species. Then, the PCR products were sequenced and edited using BioEdit. Homologies of the sequences of the present study were then searched by BLAST (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). In a BLAST search, the new sequences of Bangladeshi isolates of morphometrically identified L. auricularia (PV451617 and PV451618) were mostly identical (99.33-99.7% identities) to the previously reported Cox 1 sequences of Radix auricularia (reference gene accession no: OP084731.1), which is the older synonym of L. auricularia (Labony et al. Reference Labony, Hossain, Hatta, Dey, Mohanta, Islam, Shahiduzzaman, Hasan, Alim, Tsuji and Anisuzzaman2022). Mutations were detected in the sequences of the present study at the nucleotide positions 235, 381, 536 and 646 when compared with the reference gene (Supplementary Table 1). The sequences of the present study derived from the morphometrically identified L. luteola (PV451613 and PV451612) were mostly identical (99.24–99.39% identities) to the previously reported Cox 1 sequences of Racesina luteola (reference gene accession no: LC663695.1), which is the older synonym of L. luteola (Labony et al. Reference Labony, Hossain, Hatta, Dey, Mohanta, Islam, Shahiduzzaman, Hasan, Alim, Tsuji and Anisuzzaman2022). Mutations were detected in sequences of the present study at the nucleotide positions 19, 167 and 458 when compared with the reference gene (Supplementary Table 1). The sequences of Bangladeshi isolates of morphometrically identified I. exustus (PV451602 and PV451603) were mostly identical (99.36–99.52% identities) to the previously reported Cox 1 sequences of I. exustus (reference gene accession no: AY282587.1). Mutations were detected in sequences of the present study at the nucleotide positions 6, 90 and 530 when compared with the reference gene (Supplementary Table 1). Sequences derived from morphometrically identified P. acuta (PV459747, PV459748 and PV459749) were primarily identical (99.24% identities) to the previously reported Cox 1 sequences of P. acuta (reference gene accession no: GU247996.1). Mutations were detected in sequences of the present study at the nucleotide positions 13, 91, 236, 449 and 596 when compared with the reference gene (Supplementary Table 1). On the other hand, the newly recovered sequences of Bangladeshi isolates of morphometrically identified V. bengalensis (PV460713, PV460714 and PV460715) were mostly identical (98.78-98.94% identities) to the previously reported Cox 1 sequences of Viviparus viviparus (reference gene accession no: KY574013.1). However, no sequences had been deposited for V. bengalensis. Mutations were detected in sequences of the present study at the nucleotide positions 9, 155, 303, 382, 527, 611, 640 and 657 when compared with the reference gene (Supplementary Table 1).

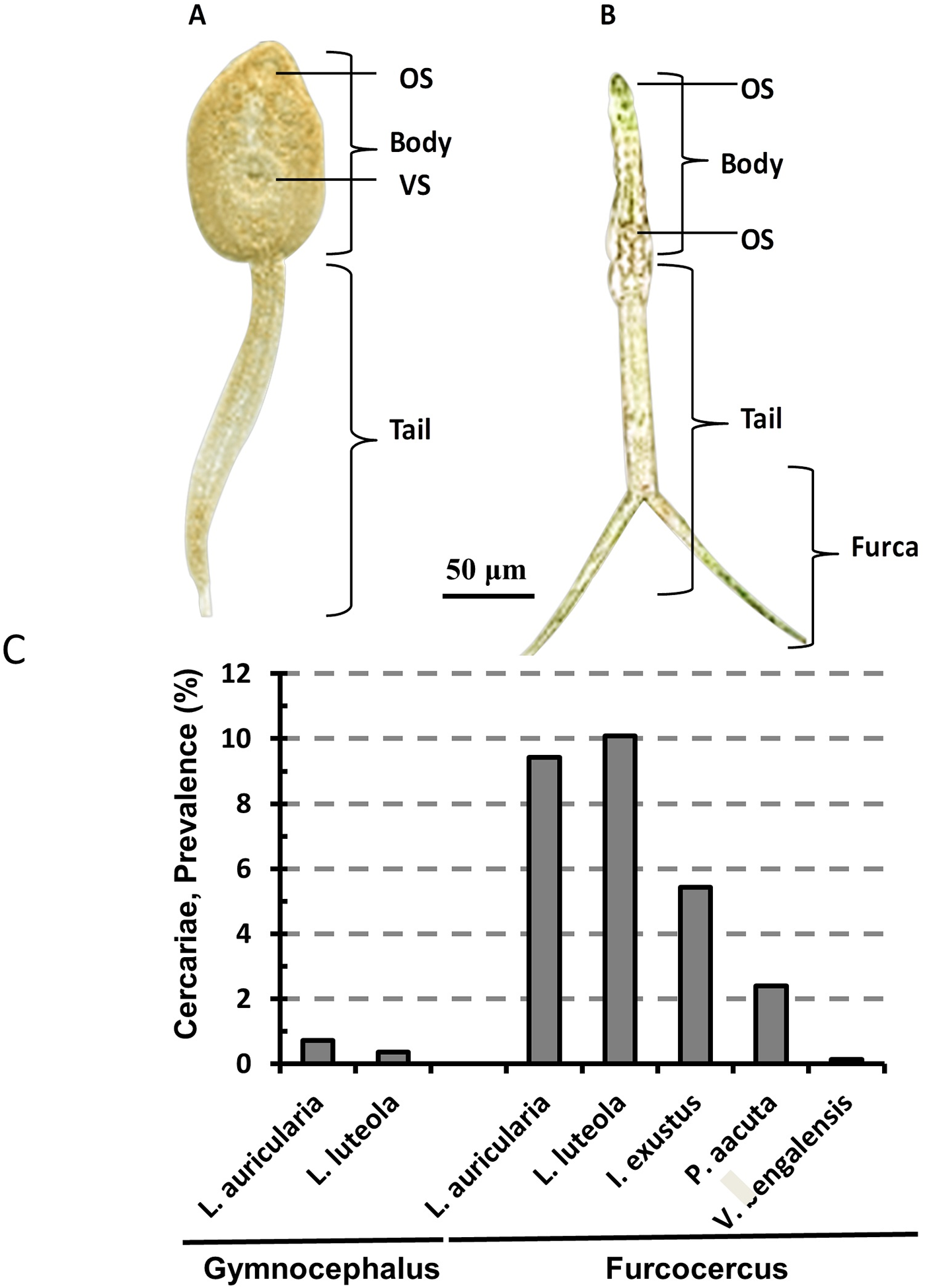

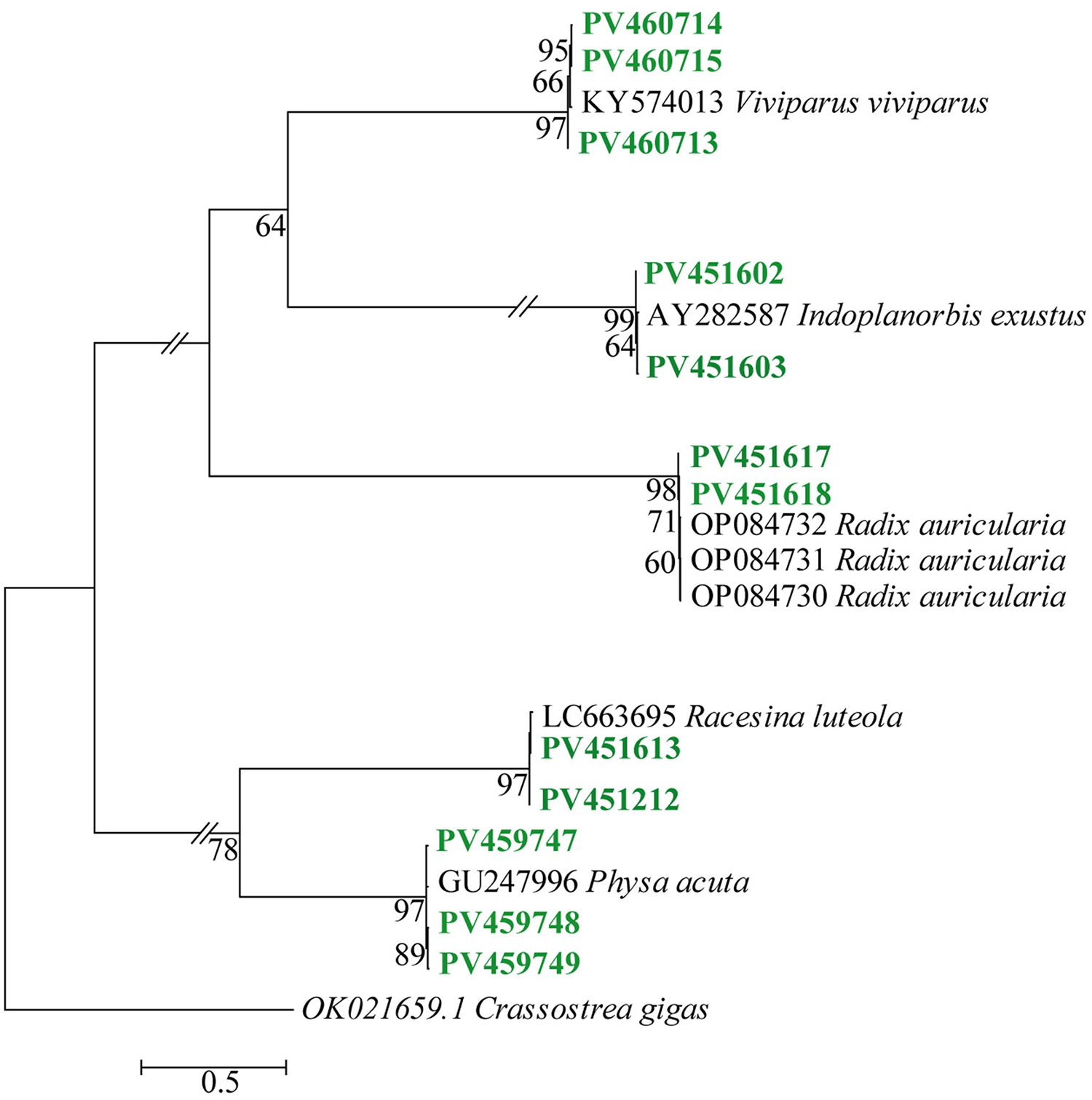

Phylogenetic analysis revealed a unique cluster

To validate snail species, the phylogenetic tree was constructed using multiple approaches, as described in the Materials and Methods section. The tree showed that each newly retrieved sequence formed unique clusters with the reference sequences of the respective species and was supported by strong bootstrap values. Sequences from our study derived L. auriclaria from a cluster with the sequences derived from L. auriclaria (Radix auriclaria) deposited in the GenBank (reference gene accession no: OP084730-OP084733). Sequences of L. luteola of this study formed distinct cluster with the of L. luteola (Racesina luteola, reference gene accessions no: LC663695) of the GenBank. Similarly, sequences of the present study obtained from I. exustus, P. acuta and V. bengalensis formed unique clusters with sequences deposited from I. exustus (reference gene accession no: AY282587), P. acuta (reference gene accession no: GU247996) and V. bengalensis (reference gene accession no: KY574013), respectively (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Cox 1-based phylogenetic analysis of sequences derived from liver flukes and blood fluke vector snails. Cox 1 sequence of Crassostera gigas was used as an out group. Green accession numbers; sequences of the present study.

Discussion

All digenean trematodes require at least 1 snail intermediate host to complete their life cycle. Snail-borne trematodiosis (SBTs) remains a major concern in many countries. Of the SBTs, liver flukes and blood fluke infections toll many lives throughout the globe. Since anthelmintic vaccines against blood flukes and liver flukes are yet to be commercialized, vector control is the main target to control SBTs. Japan, Cuba, Guadeloupe, Iran, Iraq, Lebanon, Martinique, Morocco, Oman, Puerto Rico, Saint Lucia, Saudi Arabia, Tunisia and Venezuela have controlled schistosomiosis by controlling snail intermediate hosts (Tanaka and Tsuji, Reference Tanaka and Tsuji1997; Kajihara and Hirayama, Reference Kajihara and Hirayama2011; Sokolow et al. Reference Sokolow, Wood, Jones, Lafferty, Kuris, Hsieh and de Leo2018). Therefore, confirmation of intermediate hosts of SBTs is very important. In this study, the species of snails that transmit blood flukes and liver flukes have been confirmed by conventional and molecular tools.

Although 9 species of snails have been identified but infection with Fasciola spp. was detected only from lymnaeid snails. Lymnaeid snails act as important intermediate hosts throughout the world (Malek and Cheng, Reference Malek and Cheng1974). L. auricularia and L. luteola are the principal intermediate hosts of F. gigantica (Islam et al. Reference Islam, Alam, Akter, Roy and Mondal2013). On the other hand, Lymnaea truncatula is the major host of F. hepatica (Schweizer et al. Reference Schweizer, Meli, Torgerson, Lutz, Deplazes and Braun2007). The availability of intermediate hosts is very critical to the geographical distribution of F. gigantica and F. hepatica (Malek and Cheng, Reference Malek and Cheng1974). For example, F. hepatica is only prevalent in those areas where its intermediate host, L. truncatula is available (e.g., in European countries) (Mehmood et al. Reference Mehmood, Zhang, Sabir, Abbas, Ijaz, Durrani, Saleem, Ur Rehman, Iqbal, Wang, Ahmad, Abbas, Hussain, Ghori, Ali, Khan and Li2017). In contrast, F. gigantica is only prevalent in the territories where L. auricularia and L. luteola are available (e.g., Bangladesh and West Bengal) (Islam et al. Reference Islam, Alam, Akter, Roy and Mondal2013; Itagaki et al. Reference Itagaki, Hayashi and Ohari2022a). In Bangladesh, L. truncatula has not yet been recorded; likewise, F. hepatica is yet to be reported. F. hepatica and F. gigantica co-exist in those areas where their intermediate hosts co-exist (e.g., China, Australia, Mexico and Assam) (Itagaki et al. Reference Itagaki, Hayashi and Ohari2022a). Recent studies suggest that the coexistence of both fasciolids may lead to the development of a hybrid Fasciola (Itagaki et al. Reference Itagaki, Jin, Takashima, Ohari and Angeles2022b). But hybrid form is sterile; thus, it has little impact on the development of subsequent generations (Itagaki et al. Reference Itagaki, Hayashi and Ohari2022a). In contrast, the parthenogenic form is highly fecund and able to produce fertile offspring, which can reproduce parthenogenetically using L. auricularia, L. luteola and L. truncatula (Ohari et al. Reference Ohari, Hayashi, Takashima and Itagaki2021). Parthenogenetic Fasciola exhibits ‘hybrid vigour’ (heterosis), which allow them to produce more viable offspring and maintain successive generations more effectively than the bisexual species, contributing to their high prevalence and significant disease impact in endemic areas. Therefore, this variety is more pathogenic and spreads very rapidly (Itagaki et al. Reference Itagaki, Hayashi and Ohari2022a). The parthenogenetic Fasciola has already been isolated and identified in Europe, America, Australia and many Asian countries, including Bangladesh (Itagaki et al. Reference Itagaki, Hayashi and Ohari2022a). Therefore, snail intermediate hosts are very important in the geographical distribution, propagation and existence of Fasciola spp., along with the development of new strains or varieties.

Unlike liver flukes, schistosomes do not have narrow intermediate host specificity; rather, they can utilize a large number of freshwater snails to complete their life cycle (Malek and Cheng, Reference Malek and Cheng1974; Labony et al. Reference Labony, Hossain, Hatta, Dey, Mohanta, Islam, Shahiduzzaman, Hasan, Alim, Tsuji and Anisuzzaman2022). In the present study, we detected FC in large numbers of nonoperculate and operculate snails as well. The results of the present study are consistent with those of previous studies (Labony et al. Reference Labony, Hossain, Hatta, Dey, Mohanta, Islam, Shahiduzzaman, Hasan, Alim, Tsuji and Anisuzzaman2022). Importantly, in our study, we did not get any co-shedding or co-existence of FC and GC in the same snail species. There is a phenomenon known as ‘larval antagonism’ of trematode, in which mixed infections with some species of trematode in the same snail species are mutually exclusive (Combes, Reference Combes1982; Sousa, Reference Sousa1992). Larval antagonism often involves direct predation that occurs between different species or individuals of larval trematodes within the shared intermediate host snail(s). This phenomenon can lead to the exclusion of certain species from a single host individual. The most common form of direct antagonism has been established between the radial stage of echinostomes and sporocyst of schistosomes. Schistosomes do not have a radial stage, and radia of echinostome eats of sporocyst of schistosomes; thus, species belonging to the family Echinostomatidae are often dominant over schistosomes (Combes, Reference Combes1982). Similarly, Schistosoma mansoni and Calicophoron sukari (a bovine rumen flukes) utilize Biomphalaria pfeifferi, a fresh water snail, as an intermediate host to complete their lifecycle. It has been established that development of S. mansoni is subsequently prevented by C. sukari. Interestingly, it has been observed that removal of C. sukari increases S. mansoni-infected snails by twofold. Since the radial stage is present in the life cycle of liver fluke, there is a possibility of such antagonism between schistosomes and fasciolid flukes. However, such antagonistic phenomena between schistosomes and Fasciola spp. have not yet been proved (Laidemitt et al. Reference Laidemitt, Anderson, Wearing, Mutuku, Mkoji and Loker2019).

Species of snails that act as intermediate hosts of liver flukes and schistosomes were confirmed using the Cox 1 gene-based PCR. Sequences derived from tentatively identified L. auricularia had the highest homology with those of R. auricularia, and also formed a unique cluster, further confirming the species as L. auricularia. In fact, at present the species R. auricularia is considered as Lymnaea (Radix) auricularia (Labony et al. Reference Labony, Hossain, Hatta, Dey, Mohanta, Islam, Shahiduzzaman, Hasan, Alim, Tsuji and Anisuzzaman2022). On the other hand, the sequences derived from morphometrically identified L. luteola showed the highest homology with the previously reported Cox 1 sequences of Racesina luteola, and formed a unique cluster, validating the species as Lymnaea (Racesina) luteola (Labony et al. Reference Labony, Hossain, Hatta, Dey, Mohanta, Islam, Shahiduzzaman, Hasan, Alim, Tsuji and Anisuzzaman2022). Bioinformatic analyses of newly recovered sequences of Bangladeshi isolates of I. exustus and P. acuta also unambiguously proved their species. Unfortunately, we did not found any sequence of V. bengalensis deposited in GenBank. But newly recovered sequences had considerable homologies with those of Viviparus viviparus; therefore, the genus can be considered Viviparus. There are several species in the genus Viviparus, of which V. bengalensis is considered to be distributed in Asian countries, including Bangladesh. Therefore, the present study presumed the species to be V. bengalensis.

Lymnaeid snails are large air-breathing snails and act as important intermediate hosts of many flukes. There are about 100 valid species of Lymnaea, distributed both in the tropical and temperate zones of North America, Europe and Asia (Vázquez et al. Reference Vázquez, Alda, Lounnas, Sabourin, Alba, Pointier and Hurtrez-Boussès2019). These snails are found in ponds, lakes and very slow-moving rivers; however, the highest population are found attached to underwater vegetation (Malek and Cheng, Reference Malek and Cheng1974). Of the lymnaeid snails, L. auricularia and L. luteola are very common in Bangladesh. The paddy field is the richest source of these 2 snail species in Bangladesh (Labony et al. Reference Labony, Hossain, Hatta, Dey, Mohanta, Islam, Shahiduzzaman, Hasan, Alim, Tsuji and Anisuzzaman2022). L. auricularia has also been reported in Europe and African countries, such as in Egypt (Malatji et al. Reference Malatji, Pfukenyi and Mukaratirwa2019). Similarly, Indoplanorbis is also a genus of air-breathing snails. I. exustus is the most common aquatic pulmonate mollusk and is commonly known as ram’s horn snails (Malek and Cheng, Reference Malek and Cheng1974). It has an invasive nature and very high ecological tolerance; thus, it becomes vital in veterinary and medical science (Kristensen and Ogunnowof, Reference Kristensen and Ogunnowof1987; Cowie et al. Reference Cowie, Dillon, Robinson and Smith2009). I. exustus is found in many countries: across Iran, Nepal, India, Sri Lanka, Southeast Asia (e.g., Thailand), Central Asia (e.g., Afghanistan), the Middle East (Oman and Socotra), Africa (e.g., Nigeria and the Ivory Coast) and the USA (Vázquez et al. Reference Vázquez, Alda, Lounnas, Sabourin, Alba, Pointier and Hurtrez-Boussès2019). However, I. exustus is a common snail across Southeast Asia and the Indian subcontinent. They are found in small ponds, pools and, less commonly, in paddy fields. Adult snails are highly desiccation-tolerant and can survive in the dry season buried in mud. Consequently, snail dispersal may occur through clumps of mud adhered to the bodies of cattle or buffalo. Birds can even transport them. In Bangladesh, they are commonly found adhered or attached to aquatic plants, particularly to the roots of water hyacinth (Alim et al. Reference Alim, Islam, Anisuzzaman, Farjana, Majumder, Shahiduzzaman and Mondal2007). Therefore, dispersion of I. exustus from one water body to another can quickly occur through floating water hyacinth. P. acuta lives in freshwater rivers, streams, ponds, swamps and irrigation channels. To some extent, it can survive well under temporary harsh conditions (Malek and Cheng, Reference Malek and Cheng1974). In Bangladesh, they are not highly populated. On the other hand, V. bengalensis is confined mainly to slow-moving, lowland rivers and lakes. They prefer calcareous (base-rich) waters and are often found in deep water. They usually live in dense clusters (reaching thousands of individuals) on submerged branches (Malek and Cheng, Reference Malek and Cheng1974). They are also found in canals, ponds, the water behind dams and reservoirs, but usually not in small, isolated standing waters. This species may act as an intermediate host for some other flukes (Brown, Reference Brown1994). In general, intensive agriculture promotes the survival, propagation and even spreading of freshwater snails; thus, it hampers the implementation of control strategies conducted against SBTs. Yet today, control of snails is the best option for the sustainable control the SBTs. Japanese researchers discovered the lifecycle of schistosome and identified its snail hosts in 1913, and then Japanese government launched a ‘snail picking’ program and offered children a 0.5 yen per container of snails, and destroyed. Just 7 years later, Japan started cementing irrigation canals, draining wetlands and applying molluscicides. This holistic snail control effort, along with treatment of clinical cases, led to the eradication of schistosomiosis in Japan by 1994. Following the Japan model of snail control, Guadeloupe, Iran, Iraq, Lebanon, Martinique, Morocco, Oman, Puerto Rico, Saint Lucia, Saudi Arabia, Tunisia and Venezuela have also controlled or eliminated schistosomiosis (Sokolow et al. Reference Sokolow, Wood, Jones, Swartz, Lopez, Hsieh, Lafferty, Kuris, Rickards and de Leo2016, Reference Sokolow, Wood, Jones, Lafferty, Kuris, Hsieh and de Leo2018). In fact, snail control appears to be a key intervention for achieving the World Health Assembly’s stated goal to eliminate schistosomiosis (King and Bertsch, Reference King and Bertsch2015; Sokolow et al. Reference Sokolow, Wood, Jones, Lafferty, Kuris, Hsieh and de Leo2018).

Conclusions

In the present study, for the first time, we confirmed the species of snails prevalent in Bangladesh by employing molecular tool. Our findings validated the lymnaeid snail species as L. auricularia and L. luteola as the intermediate hosts of liver flukes and schistosomes in Bangladesh. On the other hand, we confirmed I. exustus and P. acuta also have pivotal roles in the transmission cycle of schistosomatid flukes. Also, we confirmed a viviparid snail such as V. bengalensis plays essential roles in the transmission of schistosomes as well. In addition, we found that liver flukes and schistosomes do not simultaneously develop in the same snail. The information generated through this study will help to detect high-risk zones of fascioliosis and schistosomiosis in Bangladesh by mapping freshwater snail abundance and eventually will be helpful for the prioritizing of control programs in the given areas.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182025101418.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

The authors also grateful to Md. Touhidul Islam, Department of Irrigation and Water Management, Faculty of Agricultural Engineering and Technology, Bangladesh Agricultural University, Mymensingh-2202, Bangladesh, for preparing the map of the study area.

Author contributions

Conceptualization by A, MAA, and ARD; data generation by MHA, AB, URI, RP, SSL, and A; AB, MHA, and MSH wrote the draft; A, AB, MHA, MMH, and SSL analysed the data; A, ARD, MSH, and MAA revised the manuscript.

Financial support

The authors acknowledged the internal funding of the project by the University Grants Commission (UGC), Bangladesh (Project no. 2024/7/UGC).

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical standards

Not applicable.