Introduction

This article explores what the discursive logic of quasi-markets in Swedish higher education property management can reveal about the broader dynamics of politicisation and depoliticisation within the Swedish welfare state. Specifically, we examine how quasi-market reforms, ostensibly introduced to increase trust and accountability, paradoxically serve to disempower universities and facilitate their functioning as government agencies. Moreover, the neoliberal framing removes the ‘political’ from higher education governance on a discursive level while at the same time increases political control on a structural level.

Much of the literature on quasi-markets in welfare state contexts has focused on their potential to empower service users and improve quality (Le Grand, Reference Le Grand2003; Agasisti and Catalano, Reference Agasisti and Catalano2006; Dowding and John, Reference Dowding and John2009; Exley, Reference Exley2014). Many studies of New Public Management (NPM) in higher education focus on strategies of ‘academic capitalism’ (Jessop, Reference Jessop2017) that aim to reform internal governance mechanisms rather than the relationships with external stakeholders – students, public, employers. Jessop calls out ‘the penetration of finance capital and financial speculation into higher education and research’. As he points out, these aspects of the development of quasi-markets have received less attention because ‘they concern in the first instance their articulation to financial capital rather than productive capital and seem far removed from the discourses of the knowledge-based economy, the competitiveness agenda and so forth’ (2017: 861).

However, the effects of these reforms on the internal governance of welfare institutions – particularly the relationship between government and service providers – have received comparatively little attention in both Nordic and Swedish contexts. Our analysis addresses this gap by examining how Swedish quasi-markets reshape the universities’ capacity for self-governance.

Quasi-markets, often justified as neutral instruments to improve quality and efficiency, rely heavily on metaphors of consumer choice and competition. Le Grand (Reference Le Grand2003), for instance, describes students as either ‘queens’ making informed choices or ‘pawns’ passively accepting available services. Students are also cast as human capital managers, aligning with policy logics that advocate mass higher education, cost-sharing, and competition among providers as pathways to improved quality (Tight, Reference Tight2013). These narratives reinforce the view that quasi-markets are both intrinsically beneficial and instrumentally valuable (Dowding and John, Reference Dowding and John2009; Exley, Reference Exley2014), but even more importantly, the framing is one of quasi-markets as wholly depoliticised in relation to costs and the role of public bodies managing their funds and resources. Yet, as our analysis shows, the introduction of market rents and centralised property management mechanisms has been inherently political in its impact, particularly in the way it has eroded autonomy in the name of control and efficiency.

University real estate plays a multi-functional and strategic role: it provides space for education, research, community engagement, and institutional prestige (Rymarzak et al., Reference Rymarzak, den Heijer, Curvelo Magdaniel and Arkesteijn2020). At the same time, high operational costs and low space-utilisation rates have turned campus real estate into a financial burden (Kamarazaly et al., Reference Kamarazaly, Mbachu and Phipps2013; Den Heijer and Zovlas, Reference Den Heijer and Zovlas2014; Harrison and Hutton, Reference Harrison and Hutton2014). Property thus becomes a site of both vulnerability and contestation – raising the stakes for governance decisions and quasi-market reforms.

The Swedish case closely aligns with the ‘centralistic model’ of quasi-markets, where the state retains control over financing, pricing, and performance regulation, even as it adopts market-based rhetoric (Agasisti and Catalano, Reference Agasisti and Catalano2006: 248). This is characteristic of the ‘new managerialism’ described by Braun and Merrien (Reference Braun and Merrien1999), where the state governs at a distance but exerts strong oversight through performance metrics and financial instruments. As Foucault (Reference Foucault2008: 145) argues, neoliberal governance does not mean less state involvement but rather a transformation of that involvement into the logic of market competition.

In Sweden, this results in a peculiar hybrid: a centrally managed quasi-market designed to simulate competition while reinforcing state control. Some scholars argue that neoliberal reforms such as New Public Management aim to realise an economic technocracy that depoliticises public activities, including universities governed and on what basis their authority is legitimised. Rummens proposes to conceive of technocracy as an ideological stance on the basis of political legitimacy: ‘Technocracy considers political decisions legitimate to the extent that they are made by experts on the basis of their expert knowledge regarding the common good’ (Reference Rummens2023: 175). Notice that technocracy no longer refers to the will of the people. Instead, it operates in the register of ‘reason’ and refers to the common good of society (Caramani, Reference Caramani2017). It assumes that this common good is objectively given and that it can, and should, be determined by experts who have the proper knowledge for doing so (Meynaud, Reference Meynaud1964: 199–231; Fischer, Reference Fischer1990: 17–19; Caramani, Reference Caramani, Bertsou and Caramani2020: 3–4; Esmark, Reference Esmark2020: 83).

One aspect of technocratic neoliberal reforms is the introduction of technocratic depoliticisation (Compare Brown, Reference Brown2015). Under New Public Management of statecraft there have been attempts ‘to improve the performance of the state which have relied on command and control from above and choice and competition from outside’ (Cooke and Muir, Reference Cooke, Muir, Cooke and Muir2012: 5). However, this process presumes that politics can be withdrawn from the running of universities, since the politics is separate from both governance of universities and management of these resources. We argue that this is an impossibility. As in the case of Gilbert Ryle’s metaphor ‘the Ghost in the machine’, which claims that it is impossible to separate the mind from the body, it remains just as impossible to separate politics from university management (Ryle, Reference Ryle1949). NPM, through the language of quasi-markets, separates the political (intention) from the body (organisation). Just as the mind cannot be separated from the body, political intentions cannot be separated from policy interventions.

This article approaches the issue from an interpretative policy analysis perspective, applying frame analysis to political debates, legislative documents, and public discourse surrounding market rents and university real estate. Sweden provides a compelling and underexplored case. While universities operate as public agencies, the ownership and management of the bulk of their real estate are handled by Akademiska Hus AB, a limited company wholly owned by the state and expected to generate profit. Initially introduced as a cost-effective and centralised solution for managing university property, this arrangement has led to significant tensions. The imposition of market rents and cost-efficiency measures via quasi-market mechanisms contradicts Sweden’s administrative tradition that has emphasised consensus, compromise, and institutional integrity (Pierre et al., Reference Pierre, Jacobsson and Sundström2015). Moreover, this model enables a discursive sleight-of-hand where reductions in higher education funding can be reframed as fiscal surpluses for a state-owned enterprise.

Our analysis suggests that the logic underpinning quasi-market reforms in Swedish higher education is haunted by persistent ‘political ghosts in the machine’ – a metaphor capturing the mistaken belief that political control can be abstracted from institutional governance. The reform logic treats universities as neutral administrative bodies rather than politically embedded institutions, ignoring the complex interdependencies between the state and higher education institutions (HEIs). As such, quasi-markets become vehicles not only for neoliberal technocracy but also for a deeper depoliticisation of education governance. Yet, far from removing politics, these reforms redistribute control and responsibility in ways that intensify political contestation and institutional vulnerability. The implied political goal is less efficiency and cost reduction than the erosion of the autonomy of higher education in Sweden by stripping universities of decision-making, management, and control over their buildings. We therefore contend that NPM reforms such as quasi-markets do not depoliticise policymaking, rather, they obscure the politics. The adjacent reduction of university autonomy might also add further pressure on academic freedom.

Background

Since the emergence of Sweden’s universal approach to welfare in the 1940s, it has become synonymous with the social democratic approach to welfare state development. The early policies aimed to protect welfare services from the influence of private interests, and guided by a democratic governance model, led to the development of the quintessential Nordic welfare state characterised by egalitarianism, universal services, and equal access to social rights for all (Nordensvärd and Ketola, Reference Nordensvärd and Ketola2019). Yet at the same time, Sweden became an early adopter of neoliberal reforms, having initiated a slew of New Public Management reforms from the mid-1980s onwards (Knutsson et al., Reference Knutsson, Mattisson, Näsi, Lapsey and Knutsson2016), leading to substantial neoliberal changes (Ryner Reference Ryner2013; Buendía and Palazuelos Reference Buendía and Palazuelos2014; Baccaro and Pontusson Reference Baccaro and Pontusson2016; Belfrage and Kallifatides Reference Belfrage and Kallifatides2018; Svallfors and Tyllström Reference Svallfors and Tyllström2019; Hein et al., Reference Hein, Paternesi Meloni and Tridico2021). This has led to significant reductions in government spending and privatisation of welfare.

The adoption of this new policy direction meant that an ideological shift took place where the centralised policy discourse associated with the social democratic welfare state was increasingly criticised (Antikainen, Reference Antikainen2006). For example, scholars commenting on the outworkings of the 1990s economic crisis in Sweden point to how political rhetoric and public opinion both chimed with the idea that the solution was to be found in a wholesale, mostly neoliberal restructuring of the Swedish welfare state (Boréus, Reference Boréus1994; Ryner, Reference Ryner2002).

The developments in higher education dovetail the patterns of the broader welfare state change. Historically, universities hark back to a long tradition of central administrative practices and regulatory control by the central state (Nordensvärd and Ketola, Reference Nordensvärd and Ketola2019). Gradually, and often through an ambivalent process with ambiguous outcomes (Askling and Stensaker, Reference Askling and Stensaker2002), New Public Management-style reforms were implemented, administration decentralised, and resource allocation made contingent on meeting goals and achieving agreed results. Policies assuring cost-effectiveness and efficiency were introduced (Abraham, Reference Abraham2017). One of the most substantive changes has been the introduction of quasi-markets.

Quasi-markets in higher education

Quasi-markets have often been portrayed as instilling competition between universities, as they vie for students (Hall, Reference Hall2012). This has led to standardisation processes within the sector designed to enable students to make informed choices as they were ‘investing’ in an ‘education provider’ (Beach, Reference Beach2013). By replicating market practices of keeping costs low and production high, course budgets were kept to a minimum by repeating standardised courses and discouraging the development of new courses (Abraham, Reference Abraham2017).

In education policy, neoliberal thinking has tended to focus on developing strong relationships between higher education and work (Marginson, Reference Marginson2017). Ideas focused on human capital have assumed the centre stage, where university degrees are part of a pathway to the labour market, while other aspects of education have been pushed to the background (Baker, Reference Baker2011). ‘Decentralisation’, ‘goal steering’, ‘accountability’, ‘parental choice’, and ‘competition’ are introduced as the new keywords characterising the changes in Swedish education policy (Björklund et al., Reference Björklund, Edin, Fredriksson and Krueger2004: 11). For example, Nordensvärd (Reference Nordensvärd, Molesworth, Nixon and Scullions2010) describes three roles for students in a neoliberal higher education setting: students as consumers, as managers of their learning, and as human capital. Indeed, much of the analysis of neoliberal reforms on higher education has tended to focus on their impact on students (for example, Hoxby, Reference Hoxby2000; Le Grand, Reference Le Grand2003; Böhlmark and Lindahl, Reference Böhlmark and Lindahl2007). The role of the student has been individualised, moving away from the collective approach of the social democratic era (Tight, Reference Tight2013).

As the thrust of the above developments suggests, the introduction of quasi-markets in Swedish higher education were largely driven by a desire to improve student choice and the quality of the experience of using education services. As Wielemans argues, the metaphor of ‘the free market’ has been largely understood to mean competition among providers and choice among consumers (Reference Wielemans2000: 33). Todd et al. (Reference Todd, Barnoff, Moffatt, Panitch, Parada and Strumm2017: 543–544) categorises this literature on student perspectives and experiences into two main perspectives: the first explores how students are understood within a marketised university context, while the second problematises the label of ‘consumer’, and the extent it represents the roles students actually undertake, suggesting alternatives.

Quasi-market and HEI governance

In this article we focus on an aspect of the quasi-market in higher education that has received less attention to date. While models based on New Public Management and quasi-markets are now ubiquitous in higher education (Magalhães et al., Reference Magalhães, Veiga and Amaral2018), the aim of realising more effective and productive universities responsive to socioeconomic needs (Clark Reference Clark1998; Gornitzka and Maassen, Reference Gornitzka and Maassen2000; Salmi, Reference Salmi2007) has also meant that the property ownership models behind these developments can vary considerably. In the US it is normal that universities manage their own real estate. The same goes for foundation-based universities in Europe. However, for state universities the situation is often different. In this case, the relationship between the university’s operations and the real estate on which these operations depend on, becomes a central issue.

For Swedish university real estate, quasi-market reforms have meant requiring a return on investment, prioritising market competitiveness and imposing ‘market rents’ (Andersson and Söderberg, Reference Andersson and Söderberg2003). Akademiska Hus aims to profit by leasing properties to higher education institutions at market value, a practice set to continue indefinitely (Akademiska Hus, 2024). In the context of Swedish universities, which are mainly funded by the government, managed by a predetermined maximum budget with some institutional autonomy on spending, and operating on their respective campuses, the notion of market rents becomes absurd. Akademiska Hus exercises full monopoly, including pricing power in relation to its customers and tenants. Yet, at the same time it has a requirement to pay a dividend to the government.

The policy of charging market rents and the objective of making profits become increasingly fraught with tensions in the Swedish welfare discourse, as rising rents threaten the delivery of the welfare services. Our article highlights how the quasi-market operates as a way to strengthen state control over universities by ‘limiting universities’ autonomy’ and imposing the mechanisms of ‘evaluation’ and ‘control’ (Agasisti and Catalano, Reference Agasisti and Catalano2006: 249).

Methodology and empirical data

Drawing on interpretative analysis that examines the written expressions of actors involved in the discourses of Swedish higher education, we focus on understanding how different actors perceive and respond to particular policy scenarios (Durnová and Zittoun, Reference Durnová and Zittoun2011). This approach allows us to construct discursive frames that help crystallise diverse policy stances within a given frame. Following Goffman’s seminal work on framing, policy actors can contest the prevailing market discourses of higher educations by utilising frames that portray an alternative understanding of the issues, which in turn facilitates not only an opportunity to redefine the issue but for the actors to assert their roles in the policy field (Goffman, Reference Goffman1974: 21). Through our analysis of key government policy documents and media reports, we illustrate how HEIs and the government position themselves either in support of, or in opposition to, the dominant market discourse. We encapsulate these positions in key metaphors that summarise the actors’ framing of the issue.

Through interpretative social policy analysis, it is possible to frame neoliberalism as a discursive approach to articulate social policy problems and their solutions. It stands in contrast to positivist policy analysis in its emphasis on the interaction among policy actors, and on the embedded social meaning of policies, as it seeks to ‘develop a deeper, interpretative understanding of policy practices and policy processes in general, having extended their scope over time to include perspectives on discourse, narration, governmentality and practice’ (Durnová and Zittoun, Reference Durnová and Zittoun2011: 103). Interpretative analysis of policy emphasises ‘the indexical or situated nature of social categories in linguistic interaction’ (Weatherall and Walton, Reference Weatherall and Walton1999: 481) and involves the deconstruction of texts to examine their structure, deeper meaning and the resulting sociopolitical implications (Jaworski and Coupland, Reference Jaworski, Coupland, Jaworski and Coupland2000). It is an approach that focuses on how institutions and rules propagate through language (Yanow, Reference Yanow2000) and that sees policy discourses as more than mere descriptions of reality; rather, they shape reality in distinct ways (Keller, Reference Keller2004: 63) and are intertwined with dynamics of power and coercion (Keller, Reference Keller2005: 22).

The narrative function of metaphors can be understood to occur in the context of overarching frames. Frames are defined as ‘schemata of interpretation’ that enable individuals to ‘locate, perceive, identify, and label’ their surroundings and events (Goffman, Reference Goffman1974: 21). In a policymaking context, framing should be understood as ‘strategic and deliberate activity aimed at generating public support for specific policy ideas’ (Béland, Reference Béland2005: 11). Metaphors reinforce these frames by serving as linguistic devices that acquire their meaning from specific conversations and contexts (Cornelissen et al., Reference Cornelissen, Oswick, Thøger, Christensen and Phillips2008). This contextual sensitivity enhances the suitability of framing research for making ‘informed interpretations’ about how particular metaphors are used in specific situations, extending beyond merely psychological or cognitive applications (Cornelissen et al., Reference Cornelissen, Oswick, Thøger, Christensen and Phillips2008: 12). In sum, where metaphors provide vivid imagery and descriptive analogies that align with the policy ideas at play, frames offer the overarching structures for organising and interpreting the ideas.

Metaphors are direct embodiments of specific frames, serving both as their justification and tangible expression. These frames and their corresponding metaphors vary according to the local political context, ensuring they are always adapted and contextualised in ways that resonate locally. Metaphors can embody frames, with some representing a purer form of neoliberalism, while others display a more nuanced variation. We have selected this framework because it effectively illustrates how a concept like quasi-market can be contextualised to foster diverse interpretations of HEI real estate management within a welfare state context.

To frame the debate on market rents for universities, we sourced articles using Retriever MediearkivetFootnote 1 , conducting searches across major Swedish print media outlets including Aftonbladet (independent social democratic), Dagens Nyheter (independent liberal), and Svenska Dagbladet (independent moderate). Other sources have been Altinget (independent), Lundagård (a student news outlet), Tidningen Curie (run by the Swedish Research Council), Publikt, and Universitetsläraren (both union news outlets). We searched using the terms ‘Akademiska Hus AND Hyra OR Hyror (eng. Rents)’, which yielded 394 articles. We also searched for ‘Akademiska Hus AND Vinst (eng. Profits)’, resulting in thirty-three articles. Our analysis covers material from 1993 to 2023, a period that includes the initial marketisation of state property in the 1990s and the subsequent perspectives and effects that have emerged since then. After eliminating duplicates, we finalised a sample of articles representing the most significant perspectives, see Table 1.

Table 1. Analysed documents

The selection process focused on capturing the dominant positions within the debate, with our chosen sample detailed in Table 1. We reviewed the relevant publications, news articles, and other documents until reaching a saturation point where no new perspectives emerged. A potential source of bias in this research stems from our exclusion of private blogs, online discussion forums, and similar platforms. Furthermore, the material available on this topic has been relatively limited, constraining the breadth of viewpoints accessible for analysis.

Analysing metaphors: The ‘ghost in the machine’

In adapting Gilbert Ryle’s ‘the ghost in the machine’ metaphor to make sense of university governance, we explore the idea that seeing the governance and organisation of university management as entirely separate from political will is congruent with the idea of separating mind from the body: it is impossible. Ryle’s critique of Descartes’ mind-body dualism, highlighting the absurdity of separating mind (purpose, intention) from body (mechanical action), can be applied to contemporary governance when political intention is stripped away. If governance is treated purely as an efficient machine without real intention or purpose, it becomes like a ‘body without a mind’ – a system that functions mechanically but lacks direction, values, or meaningful goals.

Just as Ryle shows that mind and body cannot be separated without confusion, governance without political intention loses its essence and meaning. However, it is of course plausible that governance devoid of politics stands as the justification for reforms. A focus on efficiency removes any purposeful governance; without intentionality the actual political intention and goals of governance become obscured. This mirrors the philosophical problem of a ghost in the machine and invites us to interrogate the way in which the actual politics of technocratic systems remains obscured.

To dig deeper into how this comes to being we draw on the idea of ‘epistemic veils’ from Daniel Hausknost (Reference Hausknost2023). Hausknost argues the legitimacy of policy interventions hinges on creating distinctions between ideas that can be openly discussed and those left in obscurity. The power to ‘construct the stages of reality’ controls what is perceived as fact, thus enabling a depoliticisation of reality by detaching actions from intentional political will:

It is primarily a matter of constructing the stage on which the eternal drama of legitimation is set: of foregrounding and backgrounding, of constructing ‘epistemic veils’ that detach facts from their causal origin, of dividing reality into transparent and opaque spheres… The power to construct the stages of reality is the power to control the will/fact boundary… It is the power… to control the mechanisms of the de-politicisation and re-politicisation of reality (Hausknost, Reference Hausknost2023: 27).

Central to Hausknost’s analysis is the concept of reification, drawn from Berger and Luckmann, where human constructs are perceived as natural facts exempt from accountability: ‘the apprehension of the products of human activity as if they were something else than human products – such as facts of nature, results of cosmic laws, or manifestations of divine will’ (Berger and Luckmann, Reference Berger and Luckmann1990: 89). This reification ‘mutes’ the problem of legitimation by presenting policies as beyond scrutiny (Connolly, Reference Connolly and Connolly1984: 3). Metaphors become crucial tools in setting these epistemic veils, foregrounding some ways of understanding a problem while backgrounding others, thereby shaping which parts of governance are recognised as intentional and which are dismissed as natural or inevitable. By removing the political will and intentionality from the governance of universities, we observe a similar process as that of separating the mind from the body.

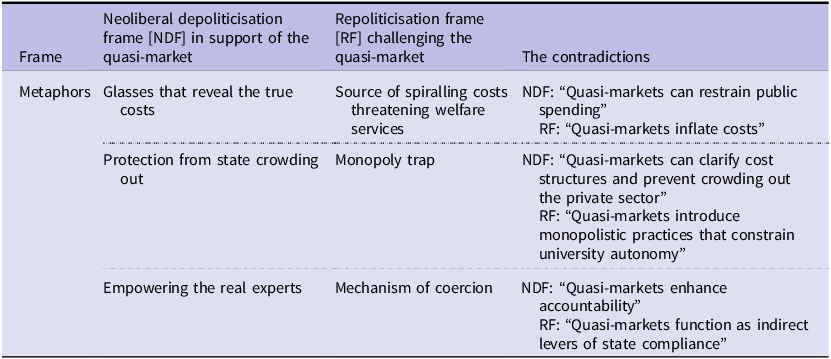

The following table summarises our methodological approach by mapping the headline findings against a framework that synthesises frame analysis with the insights gained from Ryle’s metaphor (i.e. that governance without politics is an impossible proposition). To this end, the Table 2 outlines the key metaphors employed in support of the depoliticisation frame of introducing quasi-markets in the management of Swedish university real estate, before presenting the metaphors deployed in challenging the quasi-market framing and repoliticising the reforms. In the final column we share key statements with which these metaphors are associated. These largely contradictory statements demonstrate the key aspects of the discursive processes at play.

Table 2. Metaphors of Akademiska Hus

Frames and applied metaphors for HEI real estate

From 1960 to the early 1970s, the responsibility for planning university space capacity (lokaldimensionering) was managed by programme committees located in each university city, linked to the Ministries of Education and Agriculture. Following the significant expansion of Swedish universities in the 1970s, this responsibility shifted to the Building Authority (Byggnadsstyrelsen), a new governmental body tasked with overseeing all public real estate in Sweden. In 1992, this body also took on responsibilities for the maintenance and development of new real estate projects (byggherrefunktionen) (SOU 1992:79, 1992, 76: 61).

These developments can be mapped against the rapid expansion of the welfare state from the 1960s to the 1970s, a period characterised by significant government reforms favouring centralisation, followed by the spread of neoliberal reforms in response to the economic crisis of the early 1990s, which led to the widespread adoption of New Public Management practices, described as ‘one of the most striking international trends in public administration’ (Hood, Reference Hood1991: 3).

The economic crisis had a significant impact on real estate, prompting the government to implement reforms aimed at rationalisation and retrenchment. These reforms targeted the management of all publicly owned real estate, addressing the issue of oversupply and proposing that publicly operated private entities manage these properties and lease space to public authorities (SOU, 1992: 79). Consequently, the authority overseeing all publicly owned real estate was restructured into five distinct organisations, each responsible for different segments (Andersson and Söderberg, Reference Andersson and Söderberg2003).

Akademiska Hus AB took on responsibility for all state-owned university buildings, and the introduction of quasi-market and market rents effectively placed price tags on these properties that were intended to enhance the way publicly owned real estate was utilised (SOU, 1992: 79). Consequently, university properties were exposed to quasi-market dynamics, with Akademiska Hus breaking the monopoly previously held by the Building Authority (SOU, 1992, 79: 59).

Support for a quasi-market

The primary political rationale for introducing quasi-markets is to enhance governmental efficiency by applying corporate management practice, including the implementation of market rents through the formation of a limited company. Although explicit political arguments for quasi-markets and market rents are rare, we argue they derive from the New Public Management toolkit, which emphasises safeguarding returns on investment in state assets and in the chosen organisational structure. Burnham (Reference Burnham2002, Reference Burnham2017: 12) argues that one of the most important aspects of depoliticisation is the removal of political attention – removing the political character of decision-making. The following arguments have little or no political intent regarding power, academic autonomy or academic freedom; instead, they focus primarily on costs, empowering a New Public Management technocracy and protecting the wider property market.

Cost-cutting tool

Our analysis shows that quasi-markets and market rents are seen to function as cost-cutting tools that also make the true costs of higher education explicit (GD3, GD4). The strategy aimed to instil greater financial discipline across universities, ensuring that estate management decisions reflect their full financial implications. Prior to the 1992 reforms, a significant shortcoming of the prevailing model was the assumption that space was cost-free and the main challenge for authorities was persuading the Building Authority to recognise their actual space needs (GD1: 79), with little regard for cost effectiveness.

The principle of efficiency held that state-owned real estate assets should both generate returns and give universities greater control over their use of space (GD1: 61). At the same time, the reform sought to free universities to concentrate on their core missions. The inquiry concluded that establishing a professional real estate management organisation requires substantial resources and expertise in finance, law, technology, and financial management. As university buildings are mainly special-purpose buildings, it also argued that ‘a precondition for establishing professional real estate management is that the organisation in itself can conduct development of working methods, control systems, technology, etc.’ (GD1: 71).

Preventing the state from crowding out the market

Following criticism from university representatives about introducing quasi-market governance through market rents, Akademiska Hus responded in a debate article titled ‘It’s not about usury rents’ (ED3). They argued that a 30 per cent reduction in rents would prompt a corresponding cut in government funding. The assumption was that if Akademiska Hus had to set rents, government grants would fall accordingly, reducing universities’ ability to lease spaces from private owners, thereby stifling competition and limiting choice. Therefore, maintaining a quasi-market with market rents was presented as a way to prevent the state from crowding out private providers and to preserve market functionality. Other debate articles echo this argument, further casting Akademiska Hus as a competitive market participant (ED4, ED10, ED11, ED13, NA5, NA7). Accordingly, the implementation of market rents aimed to heighten cost awareness and curb overconsumption of space (Andersson and Söderberg, Reference Andersson and Söderberg2003).

As early as 2001, the CEO of Akademiska Hus emphasised that the company follows a ‘similar-to-market’ pricing strategy mandated by the government. Responding to criticisms from institutions such as the Royal Institute of Technology, the CEO stated: ‘If we don’t show what things actually cost, it leads to poor efficiency and worse management of taxpayers’ capital’ (NA2).

Empowering experts

The reforms sought not only financial efficiency, but also a shift of authority and resources towards technocrats. According to the main governmental inquiry that informed the reform (GD1: 71), establishing a professional real estate management organisation requires a broad set of skills, and is resource intensive. It further argued that effective real estate management should be supported by an organisation capable of updating its control systems and technological capacity. This was intended to ensure that university property management could meet sector-specific needs, improving both operational efficiency and adaptability.

In a subsequent debate article, Akademiska Hus continued to assert that it follows the same rules as any other real estate company (ED3, GD4, NA7, ED12). Thus, ‘there cannot be special rules for universities’ (ED3). Similarly, a government official remarked, ‘It seems reasonable that [Akademiska Hus’s] objectives should mirror the market price for leasing premises. Setting the return requirements too low could lead to conflicts with state aid regulations’ (NA4). Taken together, these statements suggest a broad de-politisation where quasi-markets are presented as apolitical, while Akademiska Hus appears as a depoliticised ‘buffer zone between politicians’ and universities (Flinders and Buller, Reference Flinders and Buller2006: 297).

Opposition to a quasi-market

In the public debate over introducing a quasi-market for university property, critics argue that market rents would increase inefficiency and misallocate resources. Many counterarguments do not seek to repoliticise the governance and management of universities and their buildings; instead, they operate within the framework of New Public Management. They warn of escalating costs, an undue emphasis on certain forms of resources (such as buildings) over more valued capital (such as human capital), and the breakdown of market logic where quasi-markets function as local monopolies. The framing of the opposition to a quasi-market draws on three arguments. The first focuses on spiralling costs and the transition from human capital to buildings. The second claims that the quasi-market actor’s market-rate pricing effectively holds universities hostage by creating local monopolies with few viable alternatives. The most interesting critique casts market rents as a political tool, with quasi-market organisations serving as instruments for accumulating power and control by stealth.

Spiralling costs

Universities portray market rents as a serious threat to funding for teaching and research, diverting essential resources from core academic work. This view echoes longstanding concerns about the financial model for managing university properties, which places a disproportionate burden on the academic sector. A notable expression of this viewpoint appeared in a 2002 debate article by the then vice-chancellors of Chalmers, the Royal Institute of Technology, Lund University, and the University of Gothenburg, who warned that ‘the steadily increasing local costs are on the verge of draining research and higher education of resources’ (ED2). This underscores the tension between pursuing financial efficiency through market rents and supporting universities’ core missions. In 2015, Astrid Söderbergh Widding, vice-chancellor of Stockholm University, described the transfer scheme as ‘a hidden source of taxation’ (NA4) that, she argued, effectively penalises universities. She pointed out that funds earmarked for teaching and research were being redirected to generate rental income, ultimately benefiting Akademiska Hus. Her remarks highlight the persistent nature of the debate and the consistency of the debate over decades. Similar concerns were raised in the mid-1990s by a professor of real estate economics, who assessed the quasi-market scheme and described the state’s requirement for Akademiska Hus to charge market rents as ‘a special property tax targeted at higher education and research’ (ED9). University representatives have long argued that the quasi-market model and market rents severely constrain funding and, by extension, the quality of education. As one representative vividly described in Aftonbladet: ‘It has a direct impact on the quality of education. If I have higher rents, I can afford fewer teachers. It’s like a closed system with interconnected vessels’ (NA2). The analogy highlights the zero-sum nature of university budget allocations; higher costs in one area inevitably lead to reductions elsewhere. This statement connects the financial strain of market rents to potential declines in educational quality and underscores the ongoing challenge of balancing financial constraints with educational objectives.

The monopoly trap

The final critique centres on quasi-markets that, in practice, lock universities into local monopolies. This argument recurs in the news media coverage as a rebuttal to the incorporation of market mechanics into the public sector. Critics contend that the state’s push to create market conditions has instead marketised monopolies, most notably in university real estate. Given their specialised nature, university facilities – equipped with advanced laboratories and lecture halls – are considered uniquely ‘specialised’ real estate. Advocates argue that these properties should be insulated from wider property market volatility, given their tailored design and essential role in teaching and research.

Echoing the second frame, the core concern is the circular flow of public funds: universities rely on government grants, which are then used to pay market rents to a state-owned landlord. The vice-chancellors of Chalmers University of Technology, Lund University, Gothenburg University, and the Royal Institute of Technology highlighted this paradox, arguing that money earmarked for teaching and research is effectively channeled back to the state via local monopolies. They also criticised the arrangements as favouring Akademiska Hus: ‘The company [Akademiska Hus] abuses its monopoly or monopoly-like position’ (ED2).

The quotation highlights universities’ status as captive customers, bound to Akademiska Hus due to the absence of feasible alternatives. This severely limits their ability to seek other providers or secure competitive pricing, leaving them to negotiate within the constraints set by this sole provider. As university representatives told Svenska Dagbladet, ‘Akademiska Hus charges as high rents for our laboratories and lecture halls as for commercial premises in the city centre’ (NA3). Another article notes, ‘Akademiska Hus has a market share of about 70 per cent. In any other industry, on ‘real markets’, such dominance, bordering on a monopoly-like position, would prompt intervention from the Swedish Competition Authority and perhaps even from the EU’ (ED4). Consequently, universities have little scope to reduce costs by relocating.

The debate repeatedly highlights the gap between the ideal of market competition and the reality of monopolised service provision in higher education infrastructure. At its core is a dispute over what constitutes a market (ED5, ED6, ED7). As one article notes, ‘Despite many agencies’ premises being both purpose-built and fully paid off, the rents are still adjusted to a market that doesn’t truly exist’ (ED6). Others argue that ‘The arrangement of a state-owned company monopolising the rental of buildings and premises to state universities has predictably led to exorbitant rents, inevitably reducing the funding available for core academic activities’ (ED7).

Mechanism of coercion

Another frame that emerged from our analysis sees the state’s budget-balancing manoeuvre as an effort to achieve control by sleight of hand. As early as 1997, the chief financial officer at Umeå University noted, ‘The money just circulates. First, funds are allocated to our operations, and then the money is taken back in the form of rents’ (NA1). This arrangement is seen as a mechanism that compels universities to use a significant portion of their research and teaching budgets to pay high rents. These payments, in turn, allow Akademiska Hus to generate substantial profits, which are then returned to the state treasury as dividends. This approach was criticised in Dagens Nyheter as an ‘accounting manoeuvre’ (NA5), pointing to the government’s strategy of financial manipulation. This criticism also extends to other state-run entities with specialised properties, such as museums and hospitals.

This widespread application of quasi-market arrangements is seen as a state strategy to bolster public finances under the guise of covering institutional operational costs, prompting debates over the fairness and consequences for essential public services. This circular flow of funds is seen by some as a deceptive tactic by the state, essentially allocating funds to educational institutions only to reclaim them through rent. This leaves universities in the vulnerable dual role of being both beneficiaries and contributors. Critics have described this method as the state’s way of nominally investing in higher education while allocating no additional financial resources, perpetuating a financial loop.

This frustration is echoed in Svenska Dagbladet, where the wider scientific community laments the state’s reclaiming of an ever-increasing share of already scarce funds. The article underscores the irony: ‘For many within the scientific community, it is particularly frustrating that the state, on top of everything, is reclaiming a growing share of already inadequate funds. […] The funds that the Minister of Education so enthusiastically speaks about are thus taken back by the Minister of Finance’ (ED1).

An editorial on the state’s budget manoeuvres also criticises this practice, stating, ‘Call it what it is; the government milks the companies and, through backdoor channels, withdraws funds from operations to transfer them to other areas instead of allowing them to be reinvested in the activities they were initially earmarked for’ (ED7).

Despite their semi-autonomy, Swedish public agencies remain under governmental control by being made dependent on quasi-market structures and a quasi-corporate entity based on profit-seeking. This has fostered ‘mistrust of governance’, where signalling action matters more than its quality (Montin, Reference Montin2015). This creates a vicious cycle where demands for efficiency and control generate calls for even tighter control (Lindgren, Reference Lindgren2014).

This also has broader implications for academic autonomy and the culture of research autonomy. Here our findings chime with Sørensen and Olsson, who argue that parties across the political spectrum ‘hail neoliberal governance reform as an instrument to implement their own agendas through increased political control over academia’ (2017: 60). The rise of budget controls and quasi-markets has brought closer political and economic scrutiny from the state and other political actors, curtailing academic autonomy. The quasi-market reforms also sit within a wider overhaul of university governance, ‘a so-called ‘line of command’ that concentrates power in the hands of (essentially politically) appointed vice-chancellor, who, in turn, appoints all deans and heads of department’ (2017: 63).

As a result, public universities are often led by non-academics who have been selected for their ability to represent both political and private sector interests, consolidating the ‘rule by rectorate system’ while considerably decreasing academic autonomy and, arguably, academic freedom for university staff and students (Sørensen and Olsson, Reference Sørensen, Olsson, Halvorsen, Ibsen, Evans and Penderis2017: 16). The role and impact of Akademiska Hus should be seen within these broader reforms and political forces shaping Swedish academia, which limit the self-governance and autonomy of higher education institutions.

Discussion and conclusion

As the case of Akademiska Hus and market rents in Swedish HEIs demonstrates, quasi-market reforms can operate as instruments of political control. Government’s distrust of university real estate management is a key driver of neoliberal reforms that veil an attack on universities’ autonomous governance and, ultimately, undermine the academic freedom of institutions. A quasi-market organisation such as Akademiska Hus also exemplifies broader tensions between national governments and largely autonomous public agencies, illustrating how ostensibly technical and apolitical processes can be used to exert political control (Burnham, Reference Burnham2002; Flinders and Buller, Reference Flinders and Buller2006; Hay, Reference Hay2007).

The existing literature on quasi-markets, whether in the broader welfare state context (Le Grand, Reference Le Grand2003) or in higher education specifically (Exley, Reference Exley2014), tends to emphasise how such reforms are designed to increase efficiency, responsiveness, and cost transparency. Viewed through a depoliticisation lens, however, these reforms also represent a technologisation of governance, where regulatory effects and resource allocation are channeled through market logics, evaluation procedures, and cost metrics (de Leonardis, Reference de Leonardis, Borghi, de Leonardis and Procacci2013; Giancola, Reference Giancola and Moini2015). This shift redraws the boundary between the political and the non-political (Jessop, Reference Jessop2014), relocating decision-making on matters of collective interest to quasi-market organisations and, ultimately, to depoliticised modes of governance.

From this perspective, quasi-market reforms such as those applied to Swedish HEI property management contribute to what Flinders and Wood (Reference Flinders and Wood2014) describe as a specific form of social depoliticisation – one that elevates market actors and consultants as ‘champions of innovation’ while reframing political questions as technical ones. By embedding cost control, property allocation, and infrastructural oversight within an ostensibly neutral market framework, these reforms reinforce a ‘single thought’ paradigm (Hay, Reference Hay2007), narrowing policy alternatives and entrenching the prevailing logic of transnationalised and financialised capitalism.

Our case suggests that common accounts of New Public Management do not always match practice: rather than letting markets into higher education these reforms primarily expand governmental control through depoliticised management tools. Many studies of New Public Management in higher education foreground ‘academic capitalism’, focusing on changes to internal governance rather than to relationships with external stakeholders such as students, public, and employers. Yet these reforms can have ‘significant effects … on aims, activities and governance’ of higher education (Jessop, Reference Jessop2017: 816). This might be true elsewhere, but in the Swedish case, quasi-markets are less about marketisation or ideological assertion and more about structural power. In our case, the market actor, Akademiska Hus, is wholly state-owned, creating a closed loop marked by local monopoly and internal transfers: the state funds universities, universities pay market rents to Akademiska Hus, and the company then returns half its profits back to the state. Profits could also be framed as savings or cutbacks, since they are generated from the state’s own allocation. This is less a free-market exercise than a technocratic project of power and control.

Our aim is not to anoint a single correct interpretative frame or evaluate the accuracy of one frame against the other. Rather, we examine the arguments for reforming higher education governance and the far-reaching implications of these reforms in Sweden. We have also observed how the focus on university facilities in effect obscures the nature of the debate. Ideas about structures matter: in the Swedish case, quasi-markets have helped shift universities from relatively independent entities toward state agencies, narrowing the scope for the self-governance in Swedish higher education institutions which might lead to an erosion of university autonomy vis-a-vis the state. As research suggests, erosion of university autonomy might also lead to an erosion of academic freedom.

Academic freedom is deeply intertwined with the concept of institutional autonomy (Du Toit, Reference Du Toit2004; Kaya, Reference Kaya2006; Webbstock, Reference Webbstock2008). According to Higgins (Reference Higgins2000) and Robinson and Moulton (Reference Robinson, Moulton, Becker and Becker2002), academic freedom entails the liberty to teach and conduct research without constraint, and to pursue and disseminate new ideas regardless of their potential controversy. Together, academic freedom and institutional autonomy form a distinctive social contract between the state and higher education institutions (Pityana, Reference Pityana2010).

An autonomous institution is, at its core, one that acts at its own discretion and manages its own affairs. The ideals of institutional autonomy are thus closely connected to the broader principles of academic freedom (Webbstock, Reference Webbstock2008). Institutional autonomy includes the freedom to make decisions on academic matters such as curriculum design, teaching materials, pedagogical approaches, and student assessment methods (Robinson and Moulton, Reference Robinson, Moulton, Becker and Becker2002).

In a context of contested rights and eroding values, it must be emphasised that higher education institutions flourish when they are granted greater self-governance and when scholars can exercise freedom in research and inquiry. Yet, academic freedom remains precarious in many regions and is, in some cases, actively under threat (Altbach, Reference Altbach2007). As Bergan (Reference Bergan, Bergan, Guarga, Egron-Polak, Sobrinho, Tandon and Tilak2009: 48) notes, ‘university autonomy can only exist if public authorities make adequate provisions for autonomy in the legal and practical framework for higher education’.

These insights are particularly relevant in the Swedish context, where recent New Public Management reforms, such as the introduction of quasi-markets and the transfer of decision-making, management, and control over university buildings, reflect an erosion of institutional autonomy. Although a significant vein of literature on Sweden’s education reform frames this in terms of neoliberal marketisation (Björklund, Clark, et al., Reference Björklund, Clark, Edin, Fredriksson and Krueger2005; Wiborg, Reference Wiborg2013; Dahlstedt and Fejes, Reference Dahlstedt and Fejes2019; Erlandson et al., Reference Erlandson, Strandler and Karlsson2020; Blix and Jordahl, Reference Blix and Jordahl2021), others have examined its non-market effects. Lindgren et al. (Reference Lindgren, Benerdal, Carlbaum and Rönnberg2024) identify a paradox. Drawing on Knafo (Reference Knafo2020, Reference Knafo2022, Knafo et al., Reference Knafo, Dutta, Lane and Wyn-Jones2019) they contrast early neoliberal theorists such as Friedmand and Hayek, who advocated minimal bureaucracy and open competition, with the reality of the Swedish reforms that have instead produced intensified state regulation, managerial oversight and bureaucratic control.

NPM-inspired ‘managed competition’ (Enthoven, Reference Enthoven1991, Reference Enthoven1993) has empowered municipal managers to set rules, monitor providers, and enforce compliance, extending the state’s reach rather than shrinking it. In this sense, managerial governance strengthens centralised control, builds extensive auditing infrastructures, and elevates a cadre of public managers, precisely the kind of bureaucratic power neoliberals opposed (Hall, Reference Hall2012; Forssell and Ivarsson Westerberg, Reference Forssell and Ivarsson Westerberg2014; Alamaa et al., Reference Alamaa, Hall and Löfgren2024). As put forth by the Minister of Migration, Johan Forsell: ‘Our universities are government agencies operating under the authority of the government’ (NA9). This quote highlights that, regardless of gestures towards liberalisation, government rule remains steadfast. Far from embodying neoliberal ideals of freedom and market spontaneity, New Public Management in Sweden has in fact entrenched state authority and managerialism.

Such framing and sensemaking is enabled by discursive processes that position certain beliefs and values as opaque objects of reified, taken-for-granted knowledge. As Hausknost argues, an idea is garnered legitimate and beyond contention by engendering epistemic veils that obscure the links between the production of facts and their application (2023). The language surrounding Akademiska Hus exemplifies this veiling. It presents university buildings as a neutral instrument for delivering a technocratic solution to a management problem. By interrogating competing framings of these policies, we can lift the veil and recognise quasi-markets as inherently political interventions that tighten state control over universities while appearing technical and apolitical.

Author Contributions: CRediT Taxonomy

Johan Nordensvard: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Writing - original draft.

Matti Kaulio: Investigation, Writing - original draft.

Carl-Johan Sommar: Data curation, Investigation, Writing - review & editing.

Markus Ketola: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing - review & editing.