Introduction

Leishmaniasis is one of 25 neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) characterised by their impact on 100’s of millions of the global poor and a chronic lack of attention and investment (World Health Organisation, Reference Ntuli2021). Caused by the protist Leishmania spp., the disease has three primary clinical presentations: cutaneous (CL), mucocutaneous (MCL) and visceral (VL) (Georgiadou et al. Reference Georgiadou, Makaritsis and Dalekos2015). CL involves lesions on the skin and accounts for the majority of cases (Aronson et al. Reference Aronson, Herwaldt, Libman, Pearson, Lopez-Velez, Weina, Carvalho, Ephros, Jeronimo and Magill2016). MCL features infection of the mucous membranes of the respiratory tract, while VL is an infection of the internal organs such as the liver and spleen (Aronson et al. Reference Aronson, Herwaldt, Libman, Pearson, Lopez-Velez, Weina, Carvalho, Ephros, Jeronimo and Magill2016). Currently, 49% countries reporting to the WHO are considered endemic for leishmaniasis, 45% for CL specifically (Jain et al. Reference Jain, Madjou and Agua2024b).

The most recent WHO figures (2023) report 272 000 cases of CL, with the vast majority (81%) occurring in the Eastern Mediterranean Region (Figure 1) (Jain et al. Reference Jain, Madjou and Agua2024b). This is a slight reduction from the peak of 281 000 cases in 2019; however, there has been an upward trend since 2014 (Jain et al. Reference Jain, Madjou and Agua2024b). At the same time, VL case numbers fell from 31 000 to 12 000 (Jain et al. Reference Jain, Madjou and Agua2024b). Another study reported a 95% reduction in VL incidence globally from 1990 to 2021 (Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Yang, Sun, Li, Yang, Wang and Deng2025c). This positive trend is due to public health interventions focused on VL, most notably the joint eradication programme in India, Bangladesh and Nepal (Thakur et al. Reference Thakur, Joshi and Kaur2020; Jain et al. Reference Jain, Madjou and Agua2024b). In fact, VL is one of eight NTDs which have been eliminated in at least one country, in this case Bangladesh (Hietanen et al. Reference Hietanen, Pfavayi and Mutapi2025). Unfortunately, CL remains neglected – a recent review found that the total burden of CL across North Africa and the Middle East had not changed from 1990 to 2021 (EL Banna et al. Reference EL Banna, Braun, Baker, Peacker, Ma, Kibbi and Chen2025). It has also been suggested that, due to the shortage of diagnostic tools, CL case numbers are underreported and could be as high as one million per annum (de Vries and Schallig, Reference de Vries and Schallig2022).

Figure 1. The Eastern Mediterranean Region (EMR), as defined by the WHO, comprising Afghanistan, Bahrain, Djibouti, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Oman, Pakistan, Palestine, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, Tunisia, UAE, and Yemen.

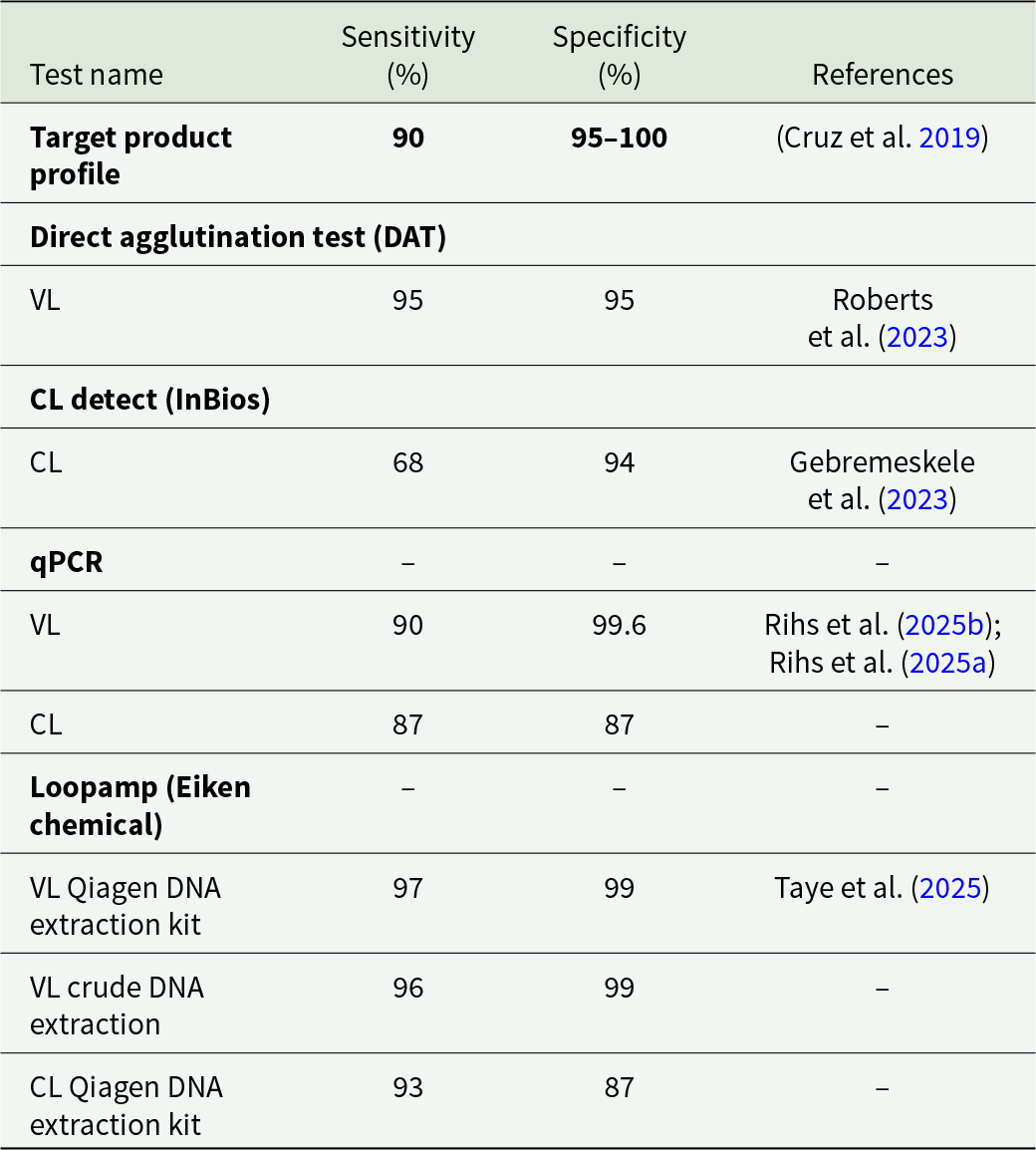

The WHO NTD Road Map to 2030 identifies diagnostics as an area in CL research where critical action is required, with a need to improve the sensitivity and affordability and a goal of 85% of cases being detected in every endemic country by 2030 (World Health Organisation, Reference Ntuli2021). A recent report concluded that these goals had not yet been met (Donadeu et al. Reference Donadeu, Gyorkos, Horstick, Lammie, Mwingira, Omondi, Pritchard, Tappero, Chan, Welsche, Agua, Madjou, Mbabazi, Warusavithana and Torres-Vitolas2025). Indeed, based on the latest figures from the WHO, only 27% of cases are being reported (Jain et al. Reference Jain, Madjou and Agua2024b). Challenges in CL diagnosis which may account for this failure include the relative lack of resources and medical infrastructure, political instability and the presence of multiple endemic species (Akhoundi et al. Reference Akhoundi, Downing, Votýpka, Kuhls, Lukeš, Cannet, Ravel, Marty, Delaunay, Kasbari, Granouillac, Gradoni and Sereno2017; de Vries and Schallig, Reference de Vries and Schallig2022). Additionally, CL lesions can be misdiagnosed as a number of communicable and non-communicable diseases such as cutaneous tuberculosis, psoriasis, purulent dermatitis and pyoderma gangrenosum due to similarities in appearance (Di Altobrando et al. Reference Di Altobrando, Misciali, Raone, Attard and Gaspari2021; Sikorska et al. Reference Sikorska, Gesing, Olszański, Roszko-Wysokińska, Szostakowska and Van Damme-Ostapowicz2022; Karaja et al. Reference Karaja, Halloum, Karaja, Daher Alhussen, hadiQatza, Mansour and Almasri2024; Shrestha et al. Reference Shrestha, Mishra, Mishra, Shrestha and Shrestha2024). To address these challenges, a target product profile (TPP) by the Foundation for Innovative Diagnostics, in collaboration with the Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative and the WHO outlines the desired characteristics for a CL diagnostic test (Cruz et al. Reference Cruz, Albertini, Barbeitas, Arana, Picado, Ruiz-Postigo and Ndung’u2019). The TPP lists criteria such as specificity (95–100%), sensitivity ( > 90%) and ease of use, both with respect to performing the test and in sample collection and preparation. The TPP also lists the need for species-level discrimination and the ability to withstand diverse and extreme storage conditions such as heat, humidity and the lack of a cold chain. Finally, the document suggests a cost per test of $1–5, with a testing device costing ≤ $2000. The goals of the TPP overlap with the WHO-coined acronym REASSURED which is a general guideline for a successful diagnostic test: Real-time connectivity, Ease of specimen collection, Affordable, Sensitive, Specific, User-friendly, Rapid and robust, Equipment-free and Deliverable to end-users (Otoo and Schlappi, Reference Otoo and Schlappi2022).

In this review, we discuss the shortcomings of existing CL diagnostics, as well as recent developments which may enable the development of a diagnostic tool matching the benchmarks in the WHO TPP by the 2030 deadline.

Aetiology and pathogenesis of CL

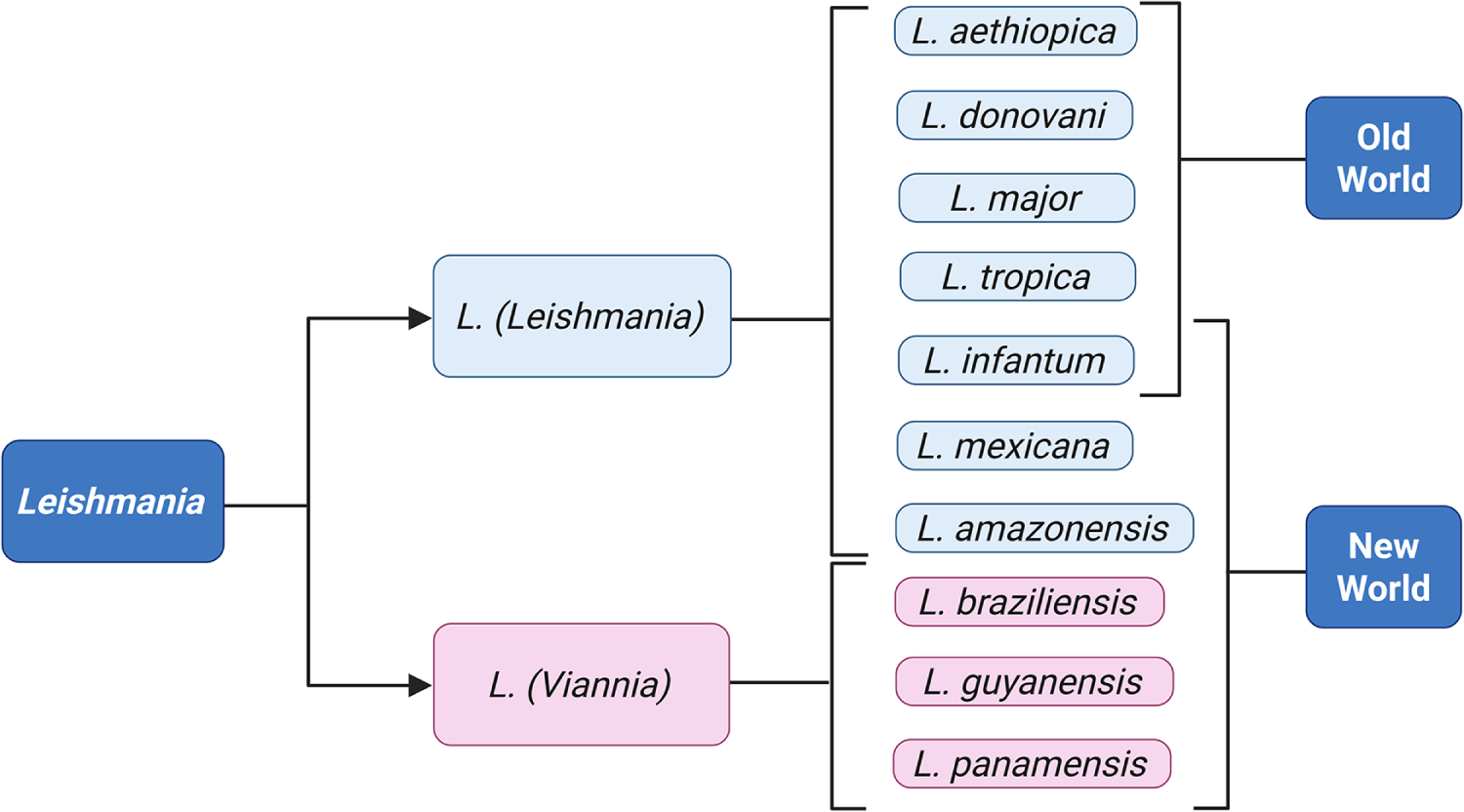

Human leishmaniasis is caused by 20 different species of Leishmania (Akhoundi et al. Reference Akhoundi, Kuhls, Cannet, Votýpka, Marty, Delaunay and Sereno2016); the most common disease-causing ones are summarised in Figure 2. Old World CL is caused by species of the Leishmania (Leishmania) subgenus, namely Leishmania major, Leishmania tropica, Leishmania aethiopica and less frequently, Leishmania infantum and Leishmania donovani (Akhoundi et al. Reference Akhoundi, Kuhls, Cannet, Votýpka, Marty, Delaunay and Sereno2016; Gurel et al. Reference Gurel, Tekin and Uzun2020). New World CL and MCL are caused by L. (Viannia) species such as Leishmania braziliensis, Leishmania guyanensis and Leishmania panamensis, although L. (Leishmania) species such as L. infantum, L. mexicana and Leishmania amazonensis are also endemic in the region (Akhoundi et al. Reference Akhoundi, Kuhls, Cannet, Votýpka, Marty, Delaunay and Sereno2016; Gurel et al. Reference Gurel, Tekin and Uzun2020).

Figure 2. The most common Leishmania species causing disease in humans. Generated using BioRender.

The disease is transmitted to the mammalian host via a bite from the insect sandfly vector (Akhoundi et al. Reference Akhoundi, Kuhls, Cannet, Votýpka, Marty, Delaunay and Sereno2016). The simplest clinical presentation is localised CL: individual self-healing lesions at the site of infection (Aronson et al. Reference Aronson, Herwaldt, Libman, Pearson, Lopez-Velez, Weina, Carvalho, Ephros, Jeronimo and Magill2016). Leishmania major infections typically follow this pattern, with lesions usually healing after 2–6 months (Auwera G and Dujardin, Reference Auwera G and Dujardin2015). In contrast, L. tropica lesions typically take 6–15 months to heal (Aronson et al. Reference Aronson, Herwaldt, Libman, Pearson, Lopez-Velez, Weina, Carvalho, Ephros, Jeronimo and Magill2016). Leishmania major CL was first distinguished by its ‘wet rural’ lesions, as opposed to the ‘dry urban’ lesions caused by L. tropica (Akhoundi et al. Reference Akhoundi, Kuhls, Cannet, Votýpka, Marty, Delaunay and Sereno2016).

Leishmania tropica is traditionally considered anthroponotic (human to vector to human transmission), as opposed to most other Leishmania infections which are zoonotic (animal to vector to human transmission) (Gurel et al. Reference Gurel, Tekin and Uzun2020; Reimão et al. Reference Reimão, Coser, Lee and Coelho2020). This urban, anthroponotic transmission pattern makes L. tropica a great threat in times of large population displacement, such as during the Syrian civil war or the recent regime change in Afghanistan (Kim et al. Reference Kim, Zieneldien, Ma and Cohen2025; Rahimi et al. Reference Rahimi, Ghatee, Habib, Farooqi, Ritmeijer, Hussain, Beg and Taylor2025). L. tropica is also considered more genetically diverse than L. major (Schwenkenbecher et al. Reference Schwenkenbecher, Wirth, Schnur, Jaffe, Schallig, Al-Jawabreh, Hamarsheh, Azmi, Pratlong and Schönian2006; Pratlong et al. Reference Pratlong, Dereure, Ravel, Lami, Balard, Serres, Lanotte, Rioux and Dedet2009; Iantorno et al. Reference Iantorno, Durrant, Khan, Sanders, Beverley, Warren, Berriman, Sacks, Cotton and Grigg2017).

Leishmania aethiopica is a CL-causing species found exclusively in Ethiopia and neighbouring countries (Blaizot et al. Reference Blaizot, Pasquier, Kone, Duvignaud and Demar2024). Ethiopia is 1 of the 10 most affected countries for CL, with an estimated 20 000 to 50 000 cases annually (Taye et al. Reference Taye, Melkamu, Tajebe, Ibarra-Meneses, Adane, Atnafu, Adem, Adane, Kassa, Asres, van Griensven, van Henten and Pareyn2024). Although there is some discrepancy in recent studies about the level of genetic diversity, it was indicated that L. aethiopica is more diverse than expected given its limited range (Hadermann et al. Reference Hadermann, Heeren, Maes, Dujardin, Domagalska and Van den Broeck2023; Yizengaw et al. Reference Yizengaw, Takele, Franssen, Gashaw, Yimer, Adem, Nibret, Yismaw, Cruz Cervera, Ejigu, Tamiru, Munshea, Müller, Weller, Cotton and Kropf2024). This diversity may account for the poor performance of commercial diagnostic tests reported in Ethiopia (Van Henten et al. Reference Van Henten, Fikre, Melkamu, Dessie, Mekonnen, Kassa, Bogale, Mohammed, Cnops, Vogt, Pareyn and Van Griensven2022; Taye et al. Reference Taye, Melkamu, Tajebe, Ibarra-Meneses, Adane, Atnafu, Adem, Adane, Kassa, Asres, van Griensven, van Henten and Pareyn2024).

As mentioned above, L. infantum and L. donovani can cause CL despite being primarily viscerotropic (Akhoundi et al. Reference Akhoundi, Kuhls, Cannet, Votýpka, Marty, Delaunay and Sereno2016). L. donovani can also cause post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis (PKDL) where, a visceral disease is followed by dermal symptoms (Reimão et al. Reference Reimão, Coser, Lee and Coelho2020). These atypical disease forms are a challenge to VL elimination efforts as they create an additional reservoir of L. donovani (Jain et al. Reference Jain, Sangma, Parida, Negi, Negi, Matlashewski and Lypaczewski2024a; Bhattarai et al. Reference Bhattarai, Rai, Uranw, Khadka, Khanal, Dahal, Pradhan, Dhakal, Monsieurs, de Gooyer, Cloots, Hasker and Van der Auwera2025). Other complex forms of CL include leishmaniasis recidivans caused by L. tropica and diffuse CL (DCL) and MCL caused by L. aethiopica (Krayter et al. Reference Krayter, Bumb, Azmi, Wuttke, Malik, Schnur, Salotra and Schönian2014, Reference Krayter, Schnur and Schönian2015; Aronson et al. Reference Aronson, Herwaldt, Libman, Pearson, Lopez-Velez, Weina, Carvalho, Ephros, Jeronimo and Magill2016; Atnafu et al. Reference Atnafu, Chanyalew, Yimam, Zeleke, Negussie, Girma, Melaku and Chanyalew2024). A recent study in Ethiopia found a lack of consensus in how different physicians classify DCL and MCL (van Henten et al. Reference van Henten, Diro, Tesfaye, Tilahun Zewdu, van Griensven and Enbiale2025). This also poses a challenge as systemic treatment is recommended for these atypical CL forms, as opposed to localised CL.

New World CL species such as L. amazonensis, L. braziliensis, L. guyanensis and L. panamensis also present a complex picture as they can cause both CL and MCL, while only Leishmania mexicana causes CL exclusively (Mann et al. Reference Mann, Frasca, Scherrer, Henao-Martínez, Newman, Ramanan and Suarez2021). L. infantum, often named Leishmania chagasi in the American context, also causes New World CL and VL but not MCL (de Vries and Schallig, Reference de Vries and Schallig2022).

Whilst self-healing lesions can be left untreated, incorrect diagnosis and treatment can result in scarring and disfigurement, as well as opportunistic secondary infections (Akuffo et al. Reference Akuffo, Sanchez, Amanor, Amedior, Kotey, Anto, Azurago, Ablordey, Owusu-Antwi, Beshah, Amoako, Phillips, Wilson, Asiedu, Ruiz-Postigo, Moreno and Mokni2023; Aminizadeh et al. Reference Aminizadeh, Mohammadi-Ghalehbin, Mohebali, Hajjaran, Zarei, Heidari, Akhondi, Alizadeh and Aghaei2024; Jaimes et al. Reference Jaimes, Patiño, Herrera, Cruz, Pérez, Correa-Cárdenas, Muñoz and Ramírez2024; Al-Alousy and Al-Nasiri, Reference Al-Alousy and Al-Nasiri2025). There are no universally efficacious treatments for CL as some Leishmania species in certain geographical settings show drug resistance (Aronson et al. Reference Aronson, Herwaldt, Libman, Pearson, Lopez-Velez, Weina, Carvalho, Ephros, Jeronimo and Magill2016). For example, antimonial resistance in L. aethiopica and L. tropica infections has been reported in Ethiopia, Iran and Pakistan (Kämink et al. Reference Kämink, Masih, Ali, Ullah, Khan, Ashraf, Pylypenko, Grobusch, Fernhout, Boer and Ritmeijer2021; Solomon et al. Reference Solomon, Greenberger, Milner, Pavlotzky, Barzilai, Schwartz, Hadayer and Baum2022; Zewdu et al. Reference Zewdu, Tessema, Zerga, van Henten and Lambert2022). Drug resistance has also been reported in L. mexicana and L. braziliensis (Ahmed et al. Reference Ahmed, Curtis, Tur-Gracia, Olatunji, Carter and Williams2020; Gonzalez-Garcia et al. Reference Gonzalez-Garcia, Rodríguez-Guzmán, Vargas-León, Aponte, Bonilla-Valbuena, Matiz-González, Clavijo-Vanegas, Duarte-Olaya, Aguilar-Buitrago, Urrea, Duitama and Echeverry2025; Ko et al. Reference Ko, Fowler, Scott and Uslan2025; Moreno-Rodríguez et al. Reference Moreno-Rodríguez, Campo-Colín, Domínguez-Díaz, Posadas-Jiménez, Matadamas-Martínez and Yépez-Mulia2025).

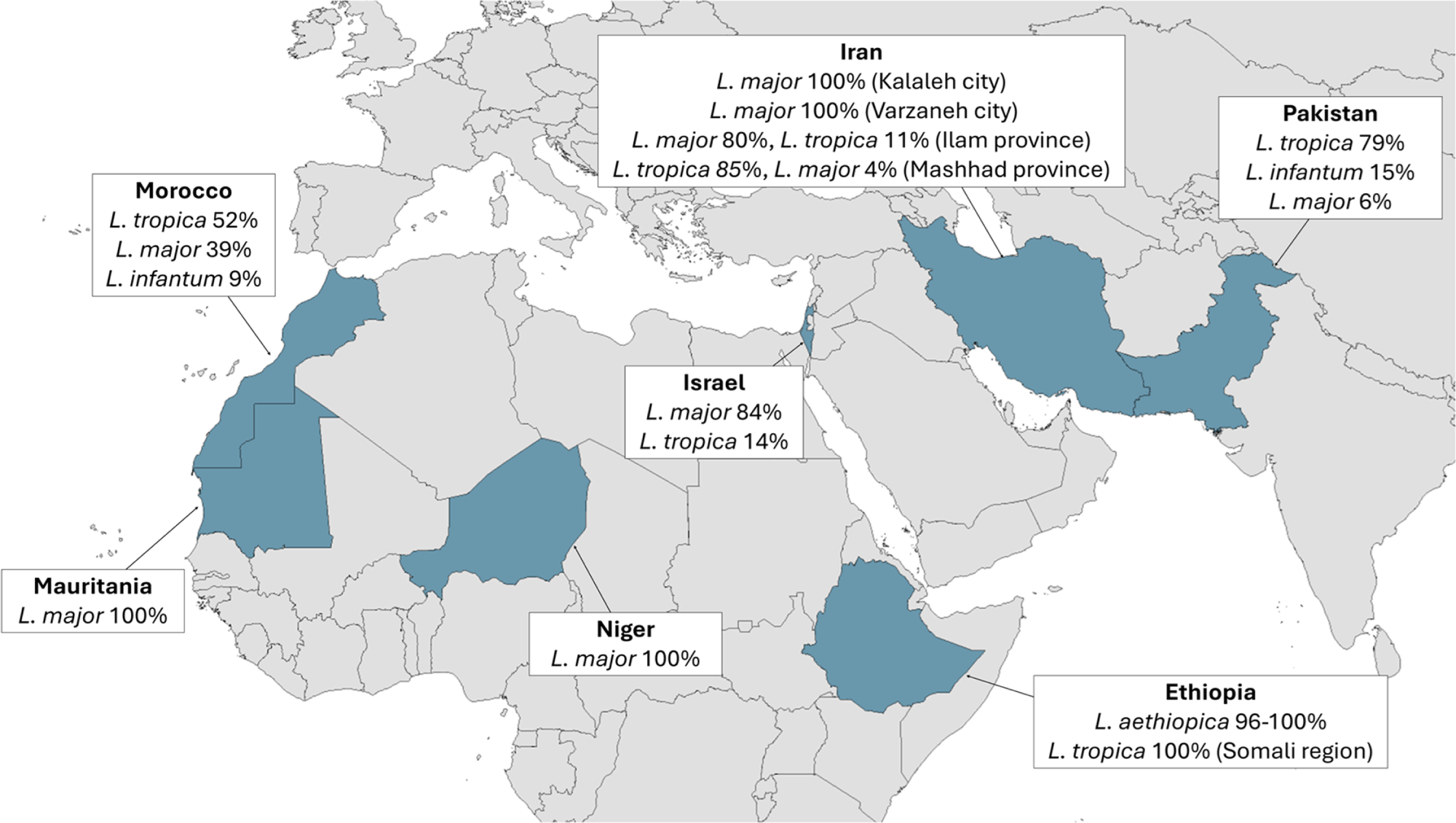

For the reasons described above, species identification is crucial to the effective treatment and control of CL. Unfortunately, due to the costly and time-consuming nature of species typing, data on the prevalence of individual CL Leishmania species remains limited and sporadic (Figure 3). A study in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province in Northern Pakistan found that 90% of CL cases were caused by L. tropica, despite the initial clinical examination finding that 73% of the lesions were dry (presumed L. tropica) and 27% were wet (presumed L. major) (Ullah et al. Reference Ullah, Khan, Niaz, Al-Garadi, Nasreen, Swelum and Said2024). This indicated that a majority of the 118 patients who had wet lesions were actually infected with L. tropica, which is an atypical presentation and demonstrates that clinical symptoms alone are insufficient for accurate diagnosis. A nationwide study found that 79% of CL cases were L. tropica, 15% were L. infantum and 6% were L. major, confirming that L. tropica is the main driver of CL in Pakistan (Naz et al. Reference Naz, Nalcaci, Hayat, Toz, Minhas, Waseem and Ozbel2024). In neighbouring Afghanistan L. tropica has historically accounted for the majority of cases, although more recent data on this is not available (Rahimi et al. Reference Rahimi, Ghatee, Habib, Farooqi, Ritmeijer, Hussain, Beg and Taylor2025). In Israel, Mauritania and Niger, the situation is reversed, with 84–100% of cases caused by L. major (Avni et al. Reference Avni, Solomon, Strauss, Sagi, Temper, Michael-Gayego, Meningher, Avitan-Hersh, Szwarcwort-Cohen, Moran-Gilad, Ollech and Schwartz2024; Blaizot et al. Reference Blaizot, Lamine, Saout, Issa, Laminou, Duvignaud, Demar and Doutchi2025; El Moctar et al. Reference El Moctar, Ouldabdallahi Moukah, Koné, Saout, Demar, Fofana, Cheikh Mohamed Vadel, Kébé, Thera, Blaizot and Ould Mohamed Salem Boukhary2025). In Iran the dominant species can be L. major or L. tropica, depending on the region (Zeinali et al. Reference Zeinali, Mohebali, Shirzadi, Hassanpour, Behkar, Gouya, Samiee and Malekafzali2023; Hayatolgheib-Moghadam et al. Reference Hayatolgheib-Moghadam, Pourzandkhanooki, Hadighi, Geraili, Alipour, Namrodi, Rampisheh and Badirzadeh2025; Marvi-Moghadam et al. Reference Marvi-Moghadam, Mohebali, Rassi, Zahraei-Ramazani, Oshaghi, Jafari, Fatemi, Arandian, Abdoli, Shareghi, Ghanei, Jalali-Zand, Veysi, Ramazanpoor, Aminian, Salehi, Khamesipour and Akhavan2025). In Morocco 52% of cases were caused by L. tropica, 39% L. major and 9% L. infantum (Baghad et al. Reference Baghad, Mouhsine, Chekairi, Amine, Saik, Lemkhayar, Lemrani, Soussi Abdallaoui, Chiheb and Riyad2025). Recent studies in Ethiopia found L. aethiopica in 96% to 100% of samples (Amare et al. Reference Amare, Mekonnen, Kassa, Addisu, Kendie, Tegegne, Abera, Tadesse, Getahun, Wondmagegn, Merdekios, Asres, van Griensven, Van der Auwera, van Henten and Pareyn2023; Tesfaye et al. Reference Tesfaye, Gebressilassie, Mekonnen, Zeynudin and Yewhalaw2025). Interestingly, a study of a recent CL outbreak in the conflict-stricken Somali region of Ethiopia, reported 100% of samples as L. tropica (Abera et al. Reference Abera, Tadesse, Beyene, Geleta, Belachew, Djirata, Kinde, Difabachew, Bishaw, Hassen, Gire, Bore, Berhe, Habtetsion, Tugga, Eyelachew, Sefer, Choukri, Coppens, Tadese, Haile, Bekele, Kebede, van der Auwera, Seife, Abte, Tollera, Hailu, Dujardin, van Griensven, Wolday, Embiale, Pareyn and Tasew2025). However, this finding should be treated with a note of caution as only 18 of the 1050 patients in the study were sampled for species typing. Nevertheless, in 99% of all 1050 patients the lesions examined were wet, unlike the typically dry lesions caused by L. tropica or L. aethiopica. The outbreak was also characterised by an unusually high number of lesions per patient, with 90% of patients having seven or more lesions.

Figure 3. Countries where OWCL species prevalence was reported in the years 2023–2025.

Equivalent data for New World CL is also sparse. A study in Roraima state in Brazil found L. braziliensis in 32% of samples, L. amazonensis in 17% of samples and L. panamensis in 13% of samples (de Almeida et al. Reference de Almeida, de Souza, Fuzari, Joya, Valdivia, Bartholomeu and Brazil2021). A further 6 species were found in 14% of samples and in 24% of samples the species could not be identified. A study in Colombia found L. panamensis in 77% of samples, L. guyanensis in 19% of samples and L. braziliensis in 4% of samples (Hoyos et al. Reference Hoyos, Rosales-Chilama, León, González and Gómez2022). In a study in Bolivia, 50% of CL samples were identified as L. braziliensis and 50% as subpopulation called L. braziliensis outlier (Torrico et al. Reference Torrico, Fernández-Arévalo, Ballart, Solano, Rojas, Ariza, Tebar, Lozano, Abras, Gascón, Picado, Muñoz, Torrico and Gállego2022). Finally, a study in Panama found L. panamensis in 59% of samples and L. guyanensis in 41% of samples, although not all results could be confirmed after further testing (Reina et al. Reference Reina, Mewa, Calzada and Saldaña2022).

Traditional diagnostic methods

As discussed, CL lesions can be visually classified as wet or dry, with additional criteria such as nodular, popular, plaque or ulcerated (Naz et al. Reference Naz, Nalcaci, Hayat, Toz, Minhas, Waseem and Ozbel2024; Ullah et al. Reference Ullah, Khan, Niaz, Al-Garadi, Nasreen, Swelum and Said2024). As mentioned, these characteristics correlate with the infecting species, but not reliably enough for accurate diagnosis (Naz et al. Reference Naz, Nalcaci, Hayat, Toz, Minhas, Waseem and Ozbel2024; Ullah et al. Reference Ullah, Khan, Niaz, Al-Garadi, Nasreen, Swelum and Said2024). CL can be confirmed by microscopic examination of a direct smear from the lesion (de Vries and Schallig, Reference de Vries and Schallig2022). A Giemsa stain allows the Leishmania amastigote forms (the mammalian stage) to be identified, however is not species specific, requires technical expertise and has limited sensitivity (50–70%) (Aronson et al. Reference Aronson, Herwaldt, Libman, Pearson, Lopez-Velez, Weina, Carvalho, Ephros, Jeronimo and Magill2016; Reimão et al. Reference Reimão, Coser, Lee and Coelho2020; de Vries and Schallig, Reference de Vries and Schallig2022). Parasite isolation by culture can improve sensitivity and allows further analytical tests such as PCR, but it prolongs the diagnosis time, is highly technical and liable to contamination (Reimão et al. Reference Reimão, Coser, Lee and Coelho2020).

Patient sampling methods include scraping, brushing, swabbing and aspiration (Reimão et al. Reference Reimão, Coser, Lee and Coelho2020). The choice of technique is influenced by cosmetic significance and patient comfort (Aronson et al. Reference Aronson, Herwaldt, Libman, Pearson, Lopez-Velez, Weina, Carvalho, Ephros, Jeronimo and Magill2016). A recent study compared methods for cutaneous lesions – skin slit, dental broach, tape dis and microbiopsy (van Henten et al. Reference van Henten, Kassa, Fikre, Melkamu, Mekonnen, Dessie, Mulaw, Bogale, Engidaw, Yeshanew, Cnops, Vogt, Moons, van Griensven and Pareyn2024). The skin slit had the highest self-reported pain score with a median of 6/10 compared to dental broach (4/10) and tape disc and microbiopsy (both 1/10). Tape disc and microbiopsy had poorer sensitivity (69–83%), compared to the dental broach (96%) and skin slit (95%). Another study comparing lancet scraping, filter paper imprints and microbiopsy samples for kDNA-PCR found that lancet scraping was the most sensitive method (99%) compared to filter paper imprints (95–96%) and microbiopsy (93–94%) (De Los Santos et al. Reference De Los Santos, Loyola, Perez-Velez, Santos, Ramírez and Valdivia2024).

Serological and immunological tests

Serological and immunological tests like the Leishmanin Skin Test have been in use for almost 100 years (Dey et al. Reference Dey, Alshaweesh, Singh, Lypaczewski, Karmakar, Klenow, Paulini, Kaviraj, Kamhawi, Valenzuela, Singh, Hamano, Satoskar, Gannavaram, Nakhasi and Matlashewski2023). The direct agglutination test (DAT), a later development where killed Leishmania promastigotes are mixed with patient blood or serum, was found to have 95% sensitivity and 95% specificity for VL in a recent meta-analysis (Roberts et al. Reference Roberts, Keddie, Rattanavong, Gomez, Bradley, Keogh, Bärenbold, Falconer, Mens, Hopkins and Ashley2023). Commercial ELISA tests for VL are also available. A recent study compared NovaLisa (Novatec), Bordier (Bordier Affinity), Ridascreen (R-Biopharm) and Vircell (Vircell) (Lévêque et al. Reference Lévêque, Battery, Delaunay, Lmimouni, Aoun, L’ollivier, Bastien, Mary, Pomares, Fillaux and Lachaud2020). The tests showed 81–94% sensitivity and 96–100% specificity, although they take 2.5–3.5 hours to perform. The four commercial ELISAs also performed poorly on samples from immunocompromised patients, with 15–42% false negative results. A separate study reported 96% sensitivity and 81% specificity for NovaLisa (Rune Stensvold et al. Reference Rune Stensvold, Vang Høst, Belkessa and Vedel Nielsen2019).

Despite the promising performance with VL samples, these kinds of tests are not recommended for CL as the infection does not produce a strong humoral response (de Vries and Schallig, Reference de Vries and Schallig2022). Additionally, serological tests do not distinguish past and active infection, and cross-reactivity has been shown with Chagas Disease, caused by the closely related Trypanosoma cruzi, but also with leprosy, tuberculosis, typhoid fever and malaria (Aronson et al. Reference Aronson, Herwaldt, Libman, Pearson, Lopez-Velez, Weina, Carvalho, Ephros, Jeronimo and Magill2016). Despite this, a meta-analysis of patents for Leishmania diagnostics in the years 2010–2022 found that 63 of the patents were based on immunological methods whereas only 33 were based on molecular methods (de Avelar et al. Reference de Avelar, Santos and Fusaro Faioli2023). Among those 33, only six were tested against L. tropica and none against L. aethiopica respectively.

PCR-based methods

PCR is an established laboratory technique for amplifying a specific DNA sequence with end-point or real-time detection (qPCR) (Auwera G and Dujardin, Reference Auwera G and Dujardin2015). Downstream analyses, such as restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) or nested PCR can improve specificity and sensitivity (Akhoundi et al. Reference Akhoundi, Downing, Votýpka, Kuhls, Lukeš, Cannet, Ravel, Marty, Delaunay, Kasbari, Granouillac, Gradoni and Sereno2017). Both approaches have been used for species identification in Leishmania spp. (Ashraf et al. Reference Ashraf, Qadeer, Bukhari, Zeb, Rasool, Salma, Shaukat, Shahzad and Osmani2025; Mohammadi Manesh et al. Reference Mohammadi Manesh, Mousavi, Mousavi, Zolfaghari, Zarei, Sharifi, Zarrinfar, Hejazi, Ataei, Mohebali and Mirhendi2025). Melting curve analyses can also be used in this way, as the melting temperature of double-stranded DNA is sequence-specific. The technique has been used to differentiate PCR products from L. major, L. tropica and L. donovani (Azam et al. Reference Azam, Singh, Gupta, Mayank, Kathuria, Sharma, Ramesh and Singh2024).

Diagnosis of leishmaniasis by PCR-based approaches has already been reviewed extensively (Auwera G and Dujardin, Reference Auwera G and Dujardin2015; Akhoundi et al. Reference Akhoundi, Downing, Votýpka, Kuhls, Lukeš, Cannet, Ravel, Marty, Delaunay, Kasbari, Granouillac, Gradoni and Sereno2017; Reimão et al. Reference Reimão, Coser, Lee and Coelho2020; Thakur et al. Reference Thakur, Joshi and Kaur2020; Nharwal et al. Reference Nharwal, Beg, Sehgal, Singh, Tiwari, Selvapandiyan and Chouhan2025). One of the most common targets is the ribosomal gene array, particularly the 18S subunit gene and the intergenic spacer ITS1 (Boulal et al. Reference Boulal, Remadi, Grigoraki, Vontas and Bendjoudi2025; Mughal et al. Reference Mughal, Khan, Lan, Abbas, Imran, Abbas, Mehmood and Ali2025). The kDNA minicircle, a DNA fragment of approximately 800bp found in the kinetoplast has also been used (Roozbehani et al. Reference Roozbehani, Tasbihi, Keyvani, Mosavizadeh, Hasanpour and Askari2025). The kinetoplast is a DNA-containing structure in the mitochondria that is unique to the Kinetoplastida, such as Leishmania and Trypanosoma spp. and has long been favoured as a PCR target due to its very high copy number reaching as many as 10 000 copies (Noyes et al. Reference Noyes, Reyburn, Bailey and Smith1998). The kinetoplast also comprises larger fragments called maxicircles containing the cytochrome b gene, which is another target (Mughal et al. Reference Mughal, Khan, Lan, Abbas, Imran, Abbas, Mehmood and Ali2025). Recently, cytochrome c oxidase I, also located on the maxicircle, has been identified as a new alternative (Mata-Somarribas et al. Reference Mata-Somarribas, Cardoso Das Graças, de Oliveira Pereira, Boité, Cantanhêde, Braga Filgueira, Fallas, Quirós-Rojas, Morelli, Melim Ferreira and Cupolillo2024). Others include cysteine protease B (cpb), glycoprotein GP63, heat-shock protein 70 (hsp70) and 7SL-RNA (Chaouch et al. Reference Chaouch, Fathallah-Mili, Driss, Lahmadi, Ayari, Guizani, Ben Said and BenAbderrazak2013; Hosseini-Safa et al. Reference Hosseini-Safa, Mohebali, Hajjaran, Akhoundi, Zarei, Arzamani and Davari2018; Azam et al. Reference Azam, Singh, Gupta, Mayank, Kathuria, Sharma, Ramesh and Singh2024).

A recent meta-analysis covering the years 2011–2022 found a pooled sensitivity of 91% and pooled specificity of 98% for qPCR (Rihs et al. Reference Rihs, Vilela, Dos Santos, de Souza Filho, Caldas, Leite and Mol2025b). An update by the same authors found that sensitivity and specificity of a qPCR approach against VL was 90% and 99.6% overall, but 86% and 100% when non-invasive sampling was used (Rihs et al. Reference Rihs, Vilela, Dos Santos, Caldas, Leite and Mol2025a). The authors cite urine samples as a non-invasive alternative to blood and bone marrow samples which are typically used in the diagnosis of VL. For CL, the sensitivity and specificity were 87% and 87% when invasive sampling was used, but only 70% and 96% using non-invasive sampling. Urine samples and lesion swabs, imprints and aspirates were classified as non-invasive methods as opposed to lesion biopsies, scrapings and smears.

The authors note that for VL samples the sensitivities reported in the original papers were often calculated using serological tests as the reference (Touria et al. Reference Touria, Kheira, Nori, Assia, Amel and Fadi2018; Iatta et al. Reference Iatta, Mendoza-Roldan, Latrofa, Cascio, Brianti, Pombi, Gabrielli and Otranto2021; Pereira et al. Reference Pereira, Ferreira-Silva, Ratkevicius, Gómez-Hérnandez, De Vito, Tanaka, Rodrigues Júnior and Moraes-Souza2021). For CL samples, because of the weaker humoral response the reference techniques used were microscopy, immunohistochemistry or a second molecular test such as conventional PCR (Vink et al. Reference Vink, Nahzat, Rahimi, Buhler, Ahmadi, Nader, Zazai, Yousufzai, van Loenen, Schallig, Picado and Cruz2018; Chaouch et al. Reference Chaouch, Aoun, Othman, Abid, Sghaier, Bouratbine and Abderrazak2019; Silgado et al. Reference Silgado, Armas, Sánchez-Montalvá, Goterris, Ubals, Temprana-Salvador, Aparicio, Chicharro, Serre-Delcor, Ferrer, Molina, García-Patos, Pumarola and Sulleiro2021). Therefore, while the gene targets are often the same, comparisons in sensitivity between VL and CL diagnostic assays should be made with caution due to these discrepancies.

Despite the promising results of various PCR-based assays in the laboratory, their deployment in the field is hampered by the requirement for expensive laboratory facilities and trained technical staff (Thakur et al. Reference Thakur, Joshi and Kaur2020). Furthermore, the reduced sensitivity to CL compared to VL, particularly when non-invasive sampling is used, is a notable drawback.

In an attempt to overcome the technical barrier, miniature PCR devices have been developed. Palm PCR, a miniature battery-powered PCR incubator, was able to detect L. tropica, L. infantum and L. major with a limit of detection of 40 pg, 4 pg and 0.4 pg, respectively (Bel Hadj Ali et al. Reference Bel Hadj Ali, Saadi-Ben Aoun, Hammami, Rhouma, Chakroun and Guizani2023). The authors created a duplex assay which could distinguish L. major, L. tropica and L. infantum and by coupling the PCR reaction to a lateral flow test (LFT) the results could be visualised in under 30 minutes. One drawback of the study was the lack of clinical samples tested. An alternative device, the miniPCR thermocycler, has been used to detect L. panamensis (Castellanos-Gonzalez et al. Reference Castellanos-Gonzalez, Cossio, Jojoa, Moen and Travi2023). The authors used the Prismo Mirage smartphone app to quantify the fluorescent signal obtained with the miniPCR transilluminator. Amplification by miniPCR had equal sensitivity (100%) to a reference qPCR assay when tested on samples from Colombia and Peru, although the time to amplification was not recorded. The miniPCR has also been used in combination with an LFT against VL samples from Ethiopia (Hagos et al. Reference Hagos, Kiros, Abdulkader, Schallig and Wolday2024). The test showed 96% sensitivity and 99% specificity relative to qPCR, giving results in just over an hour. The same assay was tested on VL samples from Spain and East Africa (van Dijk et al. Reference van Dijk, Hagos, Huggins, Carrillo, Ajala, Chicharro, Kiptanui, Solana, Abner, Wolday and Schallig2024). In Spain, miniPCR had 96% sensitivity and 97% specificity, while in East Africa it had 88% sensitivity and 100% specificity when compared to nested PCR.

A few commercial PCR kits have been developed for the diagnosis of leishmaniasis; a recent study compared STAT-NAT (Sentinel), Real-TM (Sacace) and VIASURE (CerTest) (Arnau et al. Reference Arnau, Abras, Ballart, Fernández-Arévalo, Torrico, Tebar, Llovet, Gállego and Muñoz2023). Whilst Real-TM requires −20oC storage, STAT-NAT and VIASURE both allow storage at room temperature. When tested against a range of species, VIASURE and Real-TM detected both Old World and New World species, while STAT-NAT could only detect Old World species and was therefore excluded from further analysis. When tested against clinical samples, VIASURE had 82% sensitivity and 100% specificity compared to Real-TM.

Another interesting development has been adaptive PCR, where fluorescently labelled L-DNA probes are used to model primer annealing efficiency, which allows the PCR conditions to be adjusted in real time and the amplification rate to be increased accordingly. A recent study using this technique was able to achieve 20 cycles of amplification in under 15 minutes due to the reduced cycle duration (Spurlock et al. Reference Spurlock, Alfaro, Gabella, Chugh, Pask, Baudenbacher and Haselton2025). An alternative method is microfluidic qPCR, such as that developed by GeneSoC, which was shown to be able to achieve 50 cycles in 15 minutes (Mizushina et al. Reference Mizushina, Imai, Ohama, Sato, Tanaka, Omachi, Takeuchi, Nakayama, Akeda and Maeda2025). These findings, which have not been applied to Leishmania yet, could enable the development of a cheap and rapid PCR test for leishmaniasis for use in the field.

Isothermal amplification

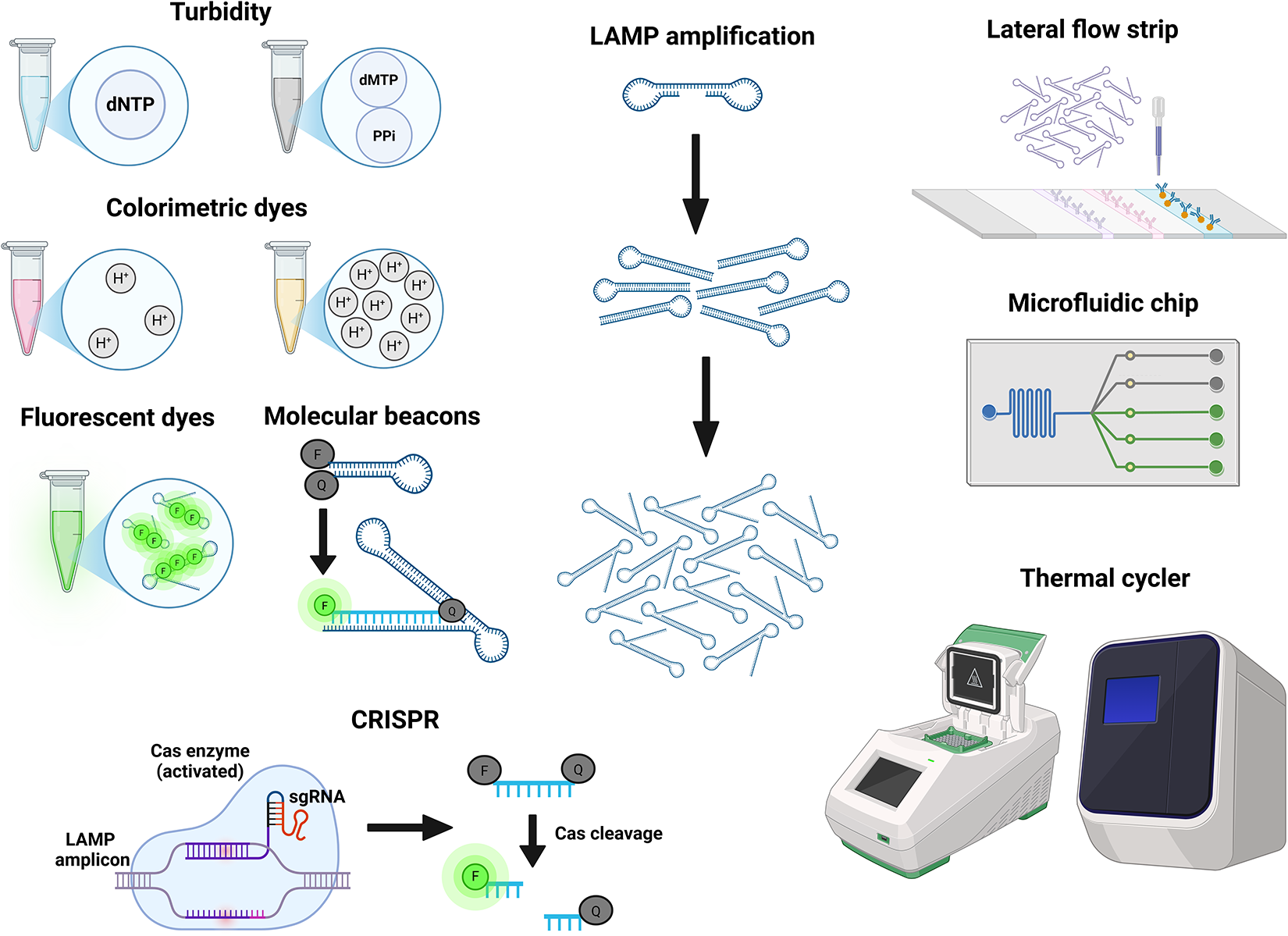

Loop-mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP) was developed in 2000 (Notomi et al. Reference Notomi, Okayama, Masubuchi, Yonekawa, Watanabe, Amino and Hase2000) and uses a thermostable Bst Polymerase with strand displacement activity. This, together with the use of a second outer pair of primers, facilitates strand separation without the high temperature melting step used in PCR and allows the whole reaction to take place at the same temperature (isothermal). A subsequent adaptation incorporating a third primer pair increases the amplification speed (Nagamine et al. Reference Nagamine, Hase and Notomi2002). Various approaches for monitoring the LAMP reaction, such as colorimetric or fluorescent dyes and turbidity caused by the byproduct pyrophosphate, are available (Figure 4) (Poirier et al. Reference Poirier, Riaño Moreno, Takaindisa, Carpenter, Mehat, Haddon, Rohaim, Williams, Burkhart, Conlon, Wilson, McClumpha, Stedman, Cordoni, Branavan, Tharmakulasingam, Chaudhry, Locker, Fernando, Balachandran, Bullen, Collins, Rimer, Horton, Munir and La Ragione2023; Jin et al. Reference Jin, Ding, Zhou, Chen, Wang and Li2024; Quero et al. Reference Quero, Aidelberg, Vielfaure, de Kermadec, Cazaux, Pandi, Pascual-Garrigos, Arce, Sakyi, Gaudenz, Federici, Molloy and Lindner2025). The assay can also be coupled with LFTs for ease of detection (Sanmoung et al. Reference Sanmoung, Sawangjaroen, Jitueakul, Buncherd, Tun, Thanapongpichat and Imwong2023). LAMP-LFT has not been used in the diagnosis of leishmaniasis, but similar approaches combining LFTs with PCR and RPA (Recombinase Polymerase Amplification, an alternative isothermal technique) have been reported (Cossio et al. Reference Cossio, Jojoa, Castro, Castillo, Osorio, Shelite, Saravia, Melby and Travi2021; Hagos et al. Reference Hagos, Kiros, Abdulkader, Schallig and Wolday2024; Nawattanapaibool et al. Reference Nawattanapaibool, Ruang-Areerate, Piyaraj, Leelayoova, Mungthin and Siripattanapipong2024; van Dijk et al. Reference van Dijk, Hagos, Huggins, Carrillo, Ajala, Chicharro, Kiptanui, Solana, Abner, Wolday and Schallig2024).

Figure 4. A visual summary of common approaches and devices used for the detection of LAMP amplification. Generated using BioRender.

The simultaneous use of three primer pairs provides a high degree of specificity. Indeed, LAMP assays have been used to detect point mutations conferring drug resistance (Sanmoung et al. Reference Sanmoung, Sawangjaroen, Jitueakul, Buncherd, Tun, Thanapongpichat and Imwong2023). Specificity can be further improved by detection with molecular beacons. A molecular beacon is a fluorophore in a quenched form, either as dsDNA or hairpin ssDNA. The fluorophore is released from the quencher when the beacon binds a specific sequence on the LAMP amplicon (Xue et al. Reference Xue, Cao, Wang, Fei, Xiong and Yang2024). This approach allows multiplexing as different fluorophores can be used with each beacon (Sherrill-Mix et al. Reference Sherrill-Mix, Hwang, Roche, Glascock, Weiss, Li, Haddad, Deraska, Monahan, Kromer, Graham-Wooten, Taylor, Abella, Ganguly, Collman, Van Duyne and Bushman2021). The technique has not been applied to Leishmania spp., but it has been tested with Trypanosoma brucei and Schistosoma mansoni (Wan et al. Reference Wan, Chen, Gao, Dong, Wong, Jia, Mak, Deng and Martins2017; Crego-Vicente et al. Reference Crego-Vicente, Fernández-Soto, García-Bernalt Diego, Febrer-Sendra and Muro2023).

An alternative approach for increasing specificity is integration with CRISPR/Cas9 (Liang et al. Reference Liang, Xie, Lv, He, Zheng, Cong, Elsheikha and Zhu2024). Briefly, the Cas endonuclease becomes activated by binding a target sequence on the LAMP amplicon with the help of a guide RNA and, subsequently, cleaves a short reporter DNA fragment to release the fluorophore from its quencher. The specific combination of LAMP and CRISPR has not been applied to leishmaniasis yet, although other studies have combined CRISPR with PCR and with RPA (Dueñas et al. Reference Dueñas, Nakamoto, Cabrera-Sosa, Huaihua, Cruz, Arévalo, Milón and Adaui2022; Yang et al. Reference Yang, Bi and Mo2024). CRISPR-assisted LAMP has also been used to diagnose toxoplasmosis, demonstrating its feasibility in parasitic infections (Liang et al. Reference Liang, Xie, Lv, He, Zheng, Cong, Elsheikha and Zhu2024).

In summary, the high sensitivity and specificity due to the use of three primer pairs, the rapid amplification time and the simple technical requirement of an isothermal heat source, make LAMP a very promising technique for a low-cost, species-specific, field diagnostic, such as that required for CL. Multiple LAMP assays for the diagnosis of leishmaniasis have been published and reviewed previously (Auwera G and Dujardin, Reference Auwera G and Dujardin2015; Akhoundi et al. Reference Akhoundi, Downing, Votýpka, Kuhls, Lukeš, Cannet, Ravel, Marty, Delaunay, Kasbari, Granouillac, Gradoni and Sereno2017; Nzelu et al. Reference Nzelu, Kato and Peters2019; Reimão et al. Reference Reimão, Coser, Lee and Coelho2020; Thakur et al. Reference Thakur, Joshi and Kaur2020; de Vries and Schallig, Reference de Vries and Schallig2022; Nharwal et al. Reference Nharwal, Beg, Sehgal, Singh, Tiwari, Selvapandiyan and Chouhan2025). The gene targets used are typically the same as those for PCR as they share the same characteristics, namely interspecies variation and high copy number.

The most recent novel assay targeting hsp70 achieved 100 fg sensitivity (Soares et al. Reference Soares, de Faria and de Avelar2024). This is a useful benchmark as it is the approximate amount of DNA in a single Leishmania parasite cell (Soares et al. Reference Soares, de Faria and de Avelar2024). The study found no cross-reactivity to T. cruzi and T. brucei, which had been observed with other LAMP assays for Leishmania spp. However, the reaction time of 60 minutes is a major drawback. Furthermore, the test is not species specific and the study focused on New World Leishmania spp. such as L. braziliensis, and whilst it includes some Old World species like L. major and L. infantum, it does not include L. tropica and L. aethiopica.

Diagnostic assays for leishmaniasis often focus on species for which effective diagnostic tests are already available, like L. donovani and L. infantum, while species which cause a substantial part of the CL burden like L. tropica and L. aethiopica remain overlooked. These choices are undoubtedly informed by existing knowledge of endemic species in the regions where researchers are based, but this is by no means fixed in stone. Recent years have shown that Leishmania species can be rapidly introduced into non-endemic countries, either by human migration or by animal reservoirs (Azami-Conesa et al. Reference Azami-Conesa, Matas Méndez, Pérez-Moreno, Carrión, Alunda, Mateo Barrientos and Gómez-Muñoz2024; Kim et al. Reference Kim, Zieneldien, Ma and Cohen2025).

To date, only three studies have designed LAMP primers to discriminate Leishmania at the species level. The first used primers targeting the kDNA minicircle of L. donovani with a limit of detection of 1 fg and no cross-reactivity against L. infantum, L. major or L. tropica (Verma et al. Reference Verma, Avishek, Sharma, Negi, Ramesh and Salotra2013). A further study used primers targeting CPB to distinguish L. major and L. tropica with a limit of detection of 20 fg and 200 fg, respectively (Chaouch et al. Reference Chaouch, Aoun, Othman, Abid, Sghaier, Bouratbine and Abderrazak2019). Most recently, one study used primers targeting kDNA minicircle of L. tropica with a limit of detection of 1 fg and no cross-reactivity for L. major or L. infantum (Taslimi et al. Reference Taslimi, Habibzadeh, Goyonlo, Akbarzadeh, Azarpour, Gharibzadeh, Shokouhy, Persson, Harandi, Mizbani and Rafati2023). All of these assays demonstrated detection levels of two cell equivalents or less.

RPA is an alternative isothermal technique which requires lower temperatures (37oC–42oC) than LAMP (Wu et al. Reference Wu, Biyani, Hirose and Takamura2023). However, the technique requires a recombinase and a single-strand DNA-binding protein in addition to the DNA polymerase which may be a challenge with respect to developing a lyophilisation protocol. Nevertheless, some recent studies have successfully used RPA to detect Leishmania spp. (Danthanarayana et al. Reference Danthanarayana, Nandy, Kourentzi, Vu, Shelite, Travi, Brgoch and Willson2023; Ghosh et al. Reference Ghosh, Chowdhury, Faisal, Khan, Hossain, Rahat, Chowdhury, Mithila, Kamal, Maruf, Nath, Kobialka, Ceruti, Cameron, Duthie, Wahed and Mondal2023; Roy et al. Reference Roy, Ceruti, Kobialka, Roy, Sarkar, Abd El Wahed and Chatterjee2023; Wu et al. Reference Wu, Biyani, Hirose and Takamura2023; Bel Hadj Ali et al. Reference Bel Hadj Ali, Saadi-Ben Aoun, Khammeri, Souguir, Harigua-Souiai, Chouaieb, Chakroun, Lemrani, Kallel, Kallel, Haddad, El Dbouni, Coler, Reed, Fathallah-Mili and Guizani2024; Kobialka et al. Reference Kobialka, Ceruti, Roy, Roy, Chowdhury, Ghosh, Hossain, Weidmann, Graf, Bueno Alvarez, Moreno, Truyen, Mondal, Chatterjee and Abd El Wahed2024; Wiggins et al. Reference Wiggins, Peng, Bushnell, Tobin, MacLeod, Du, Tobin and Dollery2024).

Sequencing-based approaches

Targeted and whole-genome DNA sequencing (WGS) has promising uses in diagnostics. Species typing of a CL infection by targeted sequencing using the Oxford Nanopore MinION platform has been reported and the technique can show evidence of mixed or hybrid infection (Imai et al. Reference Imai, Tarumoto, Amo, Takahashi, Sakamoto, Kosaka, Kato, Mikita, Sakai, Murakami, Suzuki, Maesaki and Maeda2018; Maia de Souza et al. Reference Maia de Souza, Ruedas Martins, Moyses Franco, Tuon, de Oliveira Junior, Maia da Silva, Imamura and Amato2022; Patiño et al. Reference Patiño, Ballesteros, Muñoz, Jaimes, Castillo-Castañeda, Madigan, Paniz-Mondolfi and Ramírez2023; Jaimes et al. Reference Jaimes, Patiño, Herrera, Cruz, Pérez, Correa-Cárdenas, Muñoz and Ramírez2024). The platform has likewise been used in the detection and genetic typing of other protozoan parasites such as Trypanosoma, Toxoplasma and Plasmodium spp. (Cruz-Saavedra et al. Reference Cruz-Saavedra, Ospina, Patiño, Villar, Sáenz Pérez, Cantillo-Barraza, Jaimes-Dueñez, Ballesteros, Cáceres, Vallejo and Ramírez2024; Huggins et al. Reference Huggins, Colella, Young and Traub2024; Koutsogiannis and Denny, Reference Koutsogiannis and Denny2024). While targeted sequencing can provide an indication of mixed or hybrid infection, WGS is required to distinguish between the two, as true hybrids are marked by genome-wide changes in somy and allele frequencies (Lypaczewski et al. Reference Lypaczewski, Thakur, Jain, Kumari, Paulini, Matlashewski and Jain2022; Van den Broeck et al. Reference Van den Broeck, Heeren, Maes, Sanders, Cotton, Cupolillo, Alvarez, Garcia, Tasia, Marneffe, Dujardin and Van der2023). Monitoring the emergence of hybrids is crucial as these can produce atypical forms of disease (Lypaczewski et al. Reference Lypaczewski, Thakur, Jain, Kumari, Paulini, Matlashewski and Jain2022; Bruno et al. Reference Bruno, Castelli, Li, Reale, Carra, Vitale, Scibetta, Calzolari, Varani, Ortalli, Franceschini, Gennari, Rugna and Späth2024).

WGS can also be used for surveillance, as was shown with L. donovani isolates in Nepal (Monsieurs et al. Reference Monsieurs, Cloots, Uranw, Banjara, Ghimire, Burza, Hasker, Dujardin and Domagalska2024). In the context of the current VL elimination program in Nepal, this can be used to distinguish VL cases caused by strains introduced from external sources from cases caused by endemic strains. Finally, generating new genome assemblies can provide more data on sequences and copy numbers for diagnostic targets such as hsp70, 18S and GP63 (Alonso et al. Reference Alonso, Rastrojo, López-Pérez, Requena and Aguado2016; Bussotti et al. Reference Bussotti, Gouzelou, Boité, Kherachi, Harrat, Eddaikra, Mottram, Antoniou, Christodoulou, Bali, Guerfali, Laouini, Mukhtar, Dumetz, Dujardin, Smirlis, Lechat, Pescher, Hamouchi, Lemrani, Chicharro, Llanes-Acevedo, Botana, Cruz, Moreno, Jeddi, Aoun, Bouratbine, Cupolillo and Späth2018).

Point-of-care and rapid diagnostic tests

Immunochromatographic LFTs (ICT) are widely used in the detection of VL and include IT LEISH (Bio-Rad), TruQuick (Meridian) and Kalazar Detect (InBios). In two recent studies on VL samples from Brazil and the Mediterranean, the sensitivity of these tests was 85–96% while specificity was 96–99% (Freire et al. Reference Freire, Machado de Assis, Oliveira, Moreira de Avelar, Siqueira, Barral, Rabello and Cota2019; Lévêque et al. Reference Lévêque, Battery, Delaunay, Lmimouni, Aoun, L’ollivier, Bastien, Mary, Pomares, Fillaux and Lachaud2020). However, the sensitivity with samples from immunocompromised patients was poorer, dropping to as little as 47%.

An alternative ICT specific for CL is CL Detect (InBios), targeting the peroxidoxin antigen. A recent meta-analysis of studies testing CL Detect found 68% pooled sensitivity and 94% pooled specificity (Gebremeskele et al. Reference Gebremeskele, Adane, Adem and Tajebe2023). The authors noted that the lack of consistency in the reference diagnostic used explained some of the discrepancies. Studies where microscopy was used as the reference reported higher sensitivity (83%) than those which included the more sensitive PCR as reference (48%). One of the studies reviewed compared different sampling methods. Sampling by dental broach had 64% sensitivity and 92% specificity, while lancet scraping had 83% sensitivity and 78% specificity (Grogl et al. Reference Grogl, Joya, Saenz, Quispe, Rosales, Santos, De Los Santos, Donovan, Ransom, Ramos and Cuentas2023). One study already discussed above also compared skin slit, dental broach, microbiopsy and tape disc (van Henten et al. Reference van Henten, Kassa, Fikre, Melkamu, Mekonnen, Dessie, Mulaw, Bogale, Engidaw, Yeshanew, Cnops, Vogt, Moons, van Griensven and Pareyn2024). Skin slit and dental broach performed similarly (95–96% sensitivity), tape disc and microbiopsy samples were considerably poorer (69–83% sensitivity). Notably, when skin slit PCR was used as the reference, the other three sampling methods had very low specificity (27–73%) compared to when a composite reference was used (85–100%). As multiple authors have noted that the sensitivity and specificity of a test can be distorted depending on which technique is used as a reference, more effort is needed in future studies to ensure consistency (Van Henten et al. Reference Van Henten, Fikre, Melkamu, Dessie, Mekonnen, Kassa, Bogale, Mohammed, Cnops, Vogt, Pareyn and Van Griensven2022; Gebremeskele et al. Reference Gebremeskele, Adane, Adem and Tajebe2023). While the TPP targets for sensitivity and specificity are expressed relative to microscopy, PCR is a more sensitive technique; the ideal approach is to use both as a composite reference, making it easier to compare between studies.

Loopamp is a LAMP-based test kit developed by Eiken Chemical, a spin-out company created by the authors of the LAMP technique (Feddema et al. Reference Feddema, Fernald, Keijser, Kieboom and van de Burgwal2024). This multiplex assay, with genus-specific primers targeting both the 18S rRNA gene and the kDNA minicircle, is lyophilised, allowing storage at room temperature. A recent meta-analysis found Loopamp had a pooled sensitivity of 96% for VL and 93% for CL, and 99% and 87% specificity, respectively (Taye et al. Reference Taye, Gebrie, Bogale, Getu and Churiso2025). This makes Loopamp the best-performing diagnostic test for CL to date and highlights the potential of LAMP as the most optimal technique for fulfilling the requirements of the TPP (Table 1). Also promisingly, sensitivity and specificity were 96% and 99% when crude Boil&Spin DNA extraction was used, compared to 97% and 99% with the commercial Qiagen extraction kit. As this was tested in VL samples only, caution is needed. Additionally, as there is a variety of sampling methods for CL lesions, with no consensus on which one is most effective, much work remains to be done in this area.

Table 1. The performance of various diagnostic tests for leishmaniasis as calculated by recent meta-analyses, compared to the WHO target product profile

Other improvements are also needed. Loopamp showed only 48% sensitivity on CL samples in Ethiopia (Taye et al. Reference Taye, Melkamu, Tajebe, Ibarra-Meneses, Adane, Atnafu, Adem, Adane, Kassa, Asres, van Griensven, van Henten and Pareyn2024). One drawback of that study was that tape discs were used for sample collection which have been shown elsewhere to be less sensitive than other sampling methods (van Henten et al. Reference van Henten, Kassa, Fikre, Melkamu, Mekonnen, Dessie, Mulaw, Bogale, Engidaw, Yeshanew, Cnops, Vogt, Moons, van Griensven and Pareyn2024). CL Detect also had its poorest result in Ethiopia, showing 23–31% sensitivity (Van Henten et al. Reference Van Henten, Fikre, Melkamu, Dessie, Mekonnen, Kassa, Bogale, Mohammed, Cnops, Vogt, Pareyn and Van Griensven2022). This indicates a broader problem with the genetic diversity of L. aethiopica being unaccounted for when these tests are being designed. Furthermore, there are no published trials of Loopamp in Pakistan and Syria, which have borne a large part of the CL burden in recent years. Testing clinical samples from a wide range of geographical locations is crucial. A recent study on diagnostic PCR assays for soil-transmitted helminth infections demonstrated that global genetic differences in primer binding sites can have a detrimental impact on assay sensitivity as these assays are often based on reference strains of the pathogen (Papaiakovou et al. Reference Papaiakovou, Waeschenbach, Ajibola, Ajjampur, Anderson, Bailey, Benjamin-Chung, Cambra-Pellejà, Caro, Chaima, Cimino, Cools, Cossa, Dunn, Galagan, Gandasegui, Grau-Pujol, Houlder, Ibikounlé, Jenkins, Kalua, Kjetland, Krolewiecki, Levecke, Luty, MacDonald, Mandomando, Manuel, Martínez-Valladares, Mejia, Mekonnen, Messa, Mpairwe, Muchisse, Muñoz, Mwinzi, Novela, Odiere, Sacoor, Walson, Williams, Witek-mcmanus, Littlewood, Cantacessi and Doyle2025).

Finally, despite the apparent efficacy of Loopamp outside of Ethiopia, it is only a genus-specific test. At the time of writing, there is no species-specific RDT for Leishmania spp. This feeds into a vicious cycle: because species typing in Leishmania spp. is time-consuming and requires laboratory facilities and trained staff, data on individual species prevalence is sparse, which hinders the development of future diagnostic tests. A handful of promising species-specific isothermal NAATs have been published, but further work needs to be done validating these across a variety of strains and diverse clinical samples and new assays need to be designed to cover species and geographical foci that have been previously overlooked.

Isothermal amplification devices

The earliest specialised device for isothermal amplification was the Genie I (Optigene), first used in a study in 2010 (Tomlinson et al. Reference Tomlinson, Dickinson and Boonham2010). The miniaturised real-time fluorimeter was in its third iteration (the Genie III) by the time it was trialled in the COVID-19 pandemic (Fowler et al. Reference Fowler, Armson, Gonzales, Wise, Howson, Vincent-Mistiaen, Fouch, Maltby, Grippon, Munro, Jones, Holmes, Tillyer, Elwell, Sowood, de Peyer, Dixon, Hatcher, Patrick, Laxman, Walsh, Andreou, Morant, Clark, Moore, Houghton, Cortes and Kidd2021). Although prices for the Genie are not publicly available, they can be found through secondary retailers as costing $10 000–$21 000. This is cheaper than traditional real-time PCR thermocyclers, but the price still exceeds the $2000 TPP target price (Cruz et al. Reference Cruz, Albertini, Barbeitas, Arana, Picado, Ruiz-Postigo and Ndung’u2019). More recently, Eiken Chemical have developed the LF-160, an isothermal incubator with a UV transilluminator for qualitative visual detection, costing $2000 (Sohn et al. Reference Sohn, Puri, Nguyen, Van’t Hoog, Nguyen, Nliwasa and Nabeta2019).

Most trials of Loopamp used the LF-160 (Mukhtar et al. Reference Mukhtar, Ali, Boshara, Albertini, Monnerat, Bessell, Mori, Kubota, Ndung’u and Cruz2018; Hagos et al. Reference Hagos, Kiros, Abdulkader, Arefaine, Nigus, Schallig and Wolday2021; Hossain et al. Reference Hossain, Picado, Owen, Ghosh, Chowdhury, Maruf, Khan, Rashid, Nath, Baker, Ghosh, Adams, Duthie, Hossain, Basher, Nath, Aktar, Cruz and Mondal2021). Only one study tested Loopamp in three different devices – the LF-160, the Genie III and ESE-Quant (Qiagen) (Ibarra-Meneses et al. Reference Ibarra-Meneses, Cruz, Chicharro, Sánchez, Biéler, Broger, Moreno and Carrillo2018). All three devices showed the same sensitivity, although amplification in the Genie III was much faster and matched the amplification times of the qPCR assay more closely than ESE-Quant. As the LF-160 incubator does not have a real-time function there was no equivalent data to compare.

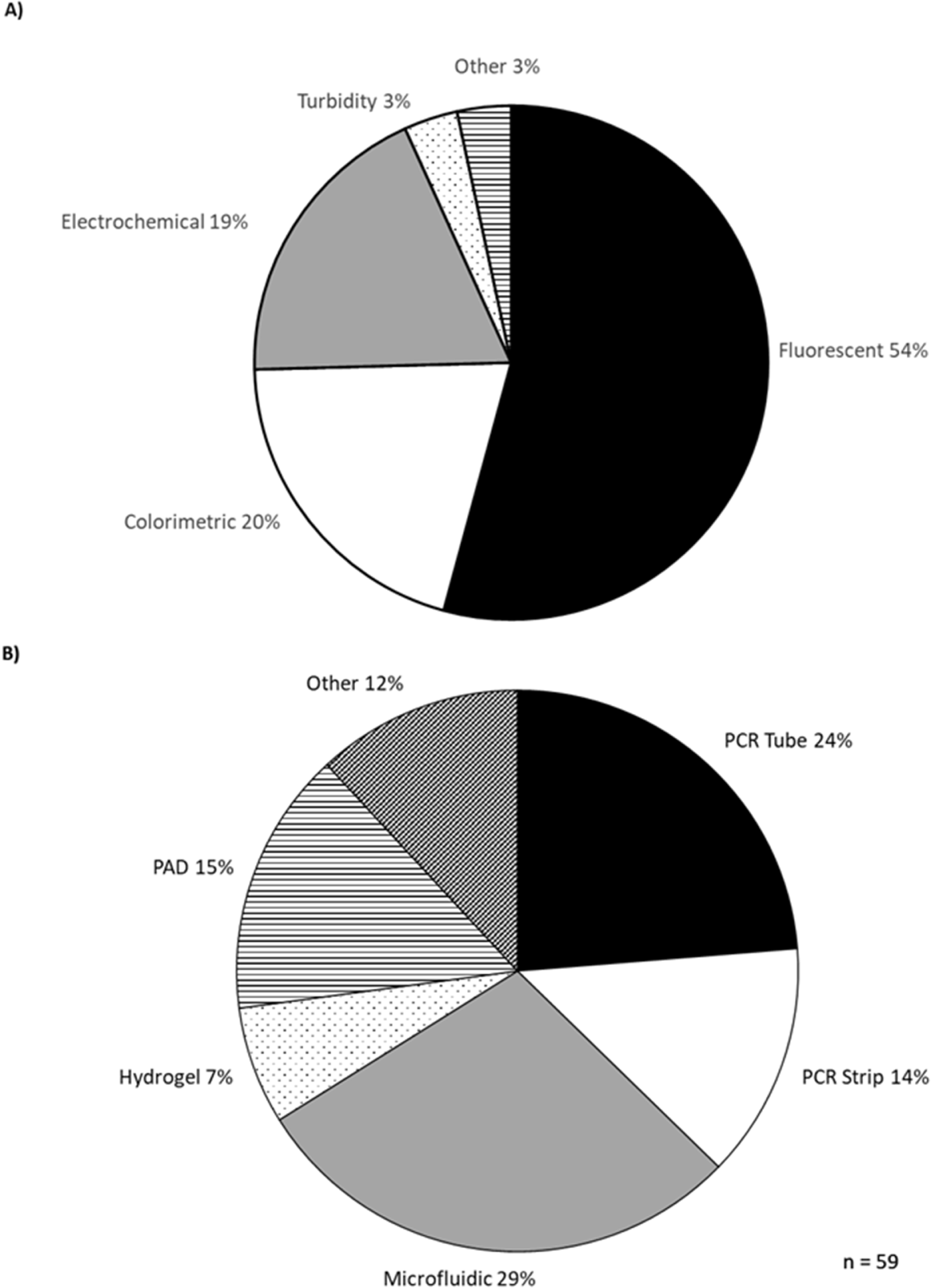

The development of isothermal diagnostic devices accelerated with the COVID-19 pandemic and many of these have been reviewed elsewhere (Das et al. Reference Das, Lin and Chuang2022; Narasimhan et al. Reference Narasimhan, Kim, Lee, Kang, Siddique, Park, Wang, Choo, Kim and Kumar2023). A selection of devices published since is summarised in the Supplementary Information. Most studies use fluorescent detection (54%), followed by colorimetric (20%) and electrochemical (19%) (Figure 5). Most devices were designed for PCR strips (14%) or individual PCR tubes (24%) (Figure 6). Microfluidic chips were the next most common format, being used in 29% of studies. Microfluidic devices are a promising development in diagnostics but they need to be custom-made for each application, while PCR tubes have a cheap, simple and uniform design, which provides versatility and is an advantage where low cost and ease of use are the priority.

Figure 5. Detection methods (A) and sample formats (B) used in new isothermal diagnostic devices.

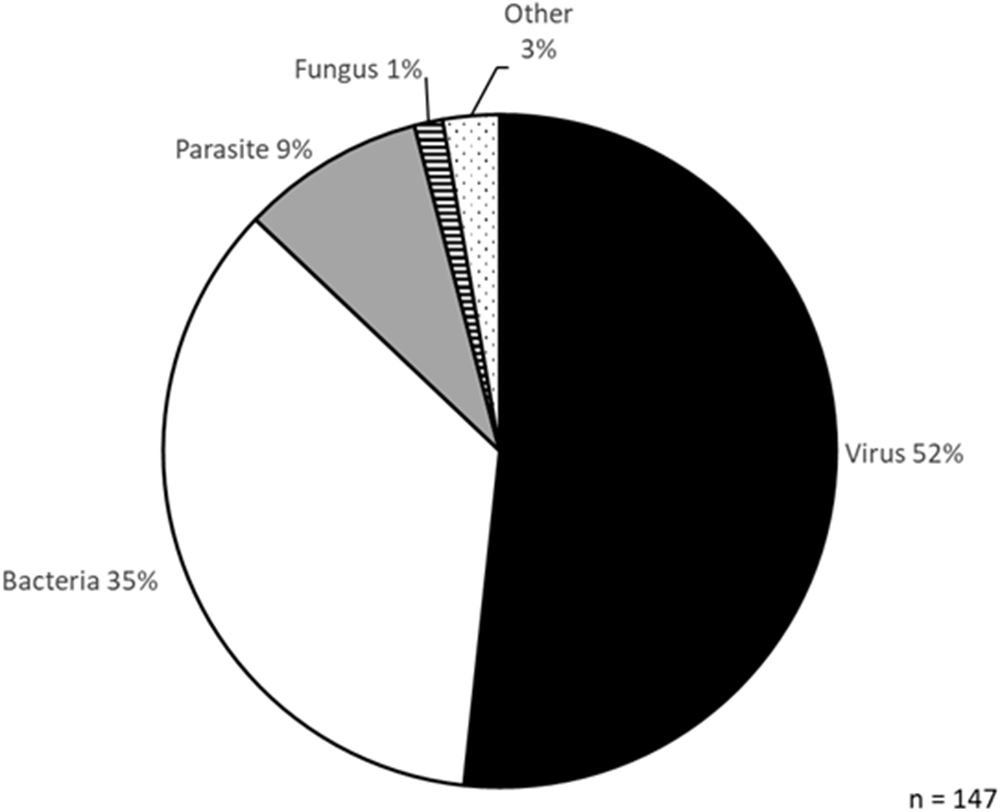

Figure 6. Classes of pathogens tested in new isothermal diagnostic devices.

Only 20 (34%) of the studies listed a manufacturing cost for their device; of those, 13 (22%) were cheaper than the mini-PCR thermocycler, which costs $600 (Castellanos-Gonzalez et al. Reference Castellanos-Gonzalez, Cossio, Jojoa, Moen and Travi2023). Crucially, all but one of the devices with a listed cost met the TPP target of $2000 or less.

Notably, the listed devices were tested on a range of different species, primarily viruses (52%) and bacteria (35%), with parasites accounting for only 9% (Figure 6). Pathogens causing NTDs accounted for 5% of the species tested. Only two studies focused on Leishmania spp. specifically. The first used fluorometric LAMP to detect 0.1 pg of L. donovani DNA (Puri et al. Reference Puri, Brar, Mittal, Madan, Srinivasan, Rawat, Moulik, Chatterjee, Gorthi, Muthuswami and Madhubala2021). The other study used electrochemical sensing coupled to RPA, detecting 10 copies/µl (<1 pg) of L. braziliensis DNA (Wu et al. Reference Wu, Biyani, Hirose and Takamura2023). Therefore, more work needs to be done testing these new devices in the diagnosis of CL and other NTDs where they are desperately needed.

Artificial intelligence

More recently, machine learning has also been tested for visual classification of CL lesions. Promisingly, studies in Brazil, Cameroon, and Colombia showed 93–96% accuracy, although a study in Libya showed only 70% accuracy (Arce-Lopera et al. Reference Arce-Lopera, Diaz-Cely and Quintero2021; Steyve et al. Reference Steyve, Steve, Ghislain, Ndjakomo and Pierre2022; Mohamed Noureldeen et al. Reference Mohamed Noureldeen, Salem Masoud and Abulqasim Almakhzoom2023; Leal et al. Reference Leal, Barroso, Trindade, Miranda and Gurgel-Gonçalves2024). Whether this is due to species-specific differences in lesion appearance, differences in skin tone, or other discrepancies in the experimental approach is currently unknown. Notably, only the Brazilian study took the causative species used in the training set into account, which the authors identified as L. braziliensis, L. amazonensis and L. guyanensis (Leal et al. Reference Leal, Barroso, Trindade, Miranda and Gurgel-Gonçalves2024). Therefore, more work remains to make sure that these approaches have high accuracy in a range of different endemic settings. In a different approach, a study in Iran tested three different algorithms and found that they could distinguish CL lesions which were responsive or non-responsive to treatment with 56–77% accuracy (Bamorovat et al. Reference Bamorovat, Sharifi, Tahmouresi, Agha Kuchak Afshari and Rashedi2025). AI has also been used to visually diagnose other cutaneous NTDs – Buruli ulcer, leprosy, scabies, mycetoma and yaws (Yotsu et al. Reference Yotsu, Ding, Hamm and Blanton2023). Buruli ulcer and scabies were correctly diagnosed with 88% sensitivity and yaws was correctly diagnosed with 79% sensitivity. However, specificity was very poor. Mycetoma was misdiagnosed as Buruli ulcer in 41% of cases, leprosy was misdiagnosed as scabies in 64% of cases and scabies was misdiagnosed as yaws in 14% of cases. Leprosy and mycetoma were correctly diagnosed in only 13% and 0% of cases, respectively.

AI has also been deployed in the detection of Leishmania spp. parasites by microscopy, with 73% to 99% accuracy (Abdelmula et al. Reference Abdelmula, Mirzaei, Güler and Süer2024; Contreras-Ramírez et al. Reference Contreras-Ramírez, Sora-Cardenas, Colorado-Salamanca, Ovalle-Bracho and Suárez2024; Kumar et al. Reference Kumar, Garg, Moudgil, Singh, Woźniak, Shafi and Ijaz2024; Sadeghi et al. Reference Sadeghi, Sadeghi, Fakhar, Zakariaei, Sadeghi and Bastani2024; Tekle et al. Reference Tekle, Dese, Girma, Adissu, Krishnamoorthy and Kwa2024; Gadri et al. Reference Gadri, Bounab, Benazi and Zerouak2025). This represents a rapid improvement as a study from 2022 found 60% accuracy for infected macrophages (Zare et al. Reference Zare, Akbarialiabad, Parsaei, Asgari, Alinejad, Bahreini, Hosseini, Ghofrani-Jahromi, Shahriarirad, Amirmoezzi, Shahriarirad, Zeighami and Abdollahifard2022). Although this approach promises to substantially reduce workload and minimise human error, it does not eliminate many of the previously discussed shortcomings of microscopy-based diagnostic techniques. In fact, only one of the studies cited used a smartphone camera to capture the images from the microscope, while the others used high resolution digital cameras (Gadri et al. Reference Gadri, Bounab, Benazi and Zerouak2025). Promisingly, the use of a smartphone camera did not compromise accuracy, which was 97%. Nevertheless, other issues such as the need for microscopy facilities and technical expertise in preparing the sample limit the applicability and relevance of these developments in a point-of-care setting.

Telemedicine

The use of mobile apps and telemedicine to augment CL diagnosis is another emerging field. A recent review on the use of telemedicine in NTDs found that it increases the capacity of the healthcare system to track the disease (Salvador et al. Reference Salvador, Wakimoto, Duarte, Lapão, Silveira and Valete2025b). One of the case studies was an app developed in Colombia for the use of patients and healthcare professionals. The app made it easier to follow-up on patients’ disease progression, allowed the collection of data in the form of lesion photographs and reporting of adverse events and made patients more likely to adhere to treatment (Cossio et al. Reference Cossio, Bautista-Gomez, Alexander, Del Castillo, Del Mar Castro, Castaño-Grajales, Gutiérrez-Poloche, Zuluaga, Vargas-Bernal, Navarro and Saravia2023). Another study in Brazil found a high rate of patient satisfaction in using telemedicine for a CL consultation, with one of the advantages listed as saving money on travel costs (Salvador et al. Reference Salvador, Oliveira, Pimentel, Lyra, Hasslocher-Moreno, Holanda, Varela, Silveira and Valete2025a). The impact of the WHO’s own SkinNTDs app was recently studied in Cameroon (Moungui et al. Reference Moungui, Tonkoung Iyawa, Nana-Djeunga, Ruiz-Postigo and Carrion2025). The app scored highly on user satisfaction (3.3/4.5), quality of information (3.6/5) and impact on knowledge and diagnosis (3.9/5), although 57% of participants had limited experience with skin NTDs and reported encountering less than one case per month. In a comparable study conducted in Ghana and Kenya, where only 22% of participants reported encountering less than one skin NTD case per month, the app scored 3.8/5 on user satisfaction, 4/5 on quality of information and 4.5/5 on impact (Frej et al. Reference Frej, Cano, Ruiz-Postigo, Macharia, Phillips, Amoako and Carrion2022). While these reports are encouraging with regard to skin NTDs generally, it would be useful to see equivalent data in countries which are more affected by CL in particular. Another useful tool is Lesionia, an example of Digital Systems for Data Management, which allows clinicians and healthcare workers in different countries to log and record epidemiological data on CL (Harigua-Souiai et al. Reference Harigua-Souiai, Salem, Hariga, Saadi, Souguir, Chouaieb, Adedokun, Mkada, Moussa, Fathallah-Mili, Lemrani, Haddad, Oduola, Souiai, Ali and Guizani2025).

The AI tools discussed above can be integrated with a telemedicine app to allow for a rapid triage step which can then lead to a referral for further testing. The use of AI image analysis tools in this way is already recommended by the WHO in the diagnosis of tuberculosis (World Health Organization, 2022). Remote diagnosis of CL by a mobile app was also successfully used on a small scale in Nepal during the COVID-19 pandemic (Parajuli and Prajapati, Reference Parajuli and Prajapati2023).

Conclusions

A number of advances have been made in recent years that bring the goals of the TPP closer to being realised. Most of the ingredients for a good diagnostic test for CL already exist, albeit scattered across different disciplines and research areas. The serological CL Detect RDT has achieved 93% specificity over various studies, but its sensitivity of 68% is far below the 95% target in the TPP (Gebremeskele et al. Reference Gebremeskele, Adane, Adem and Tajebe2023). The isothermal Loopamp RDT improved on this substantially, with 93% sensitivity and 87% specificity (Taye et al. Reference Taye, Gebrie, Bogale, Getu and Churiso2025). This is also an improvement on qPCR which was found to have 87% sensitivity and 87% specificity (Rihs et al. Reference Rihs, Vilela, Dos Santos, Caldas, Leite and Mol2025a). However, both RDTs performed very poorly on samples from Ethiopia, which highlights the country as being particularly neglected in terms of readily available diagnostic tools (Van Henten et al. Reference Van Henten, Fikre, Melkamu, Dessie, Mekonnen, Kassa, Bogale, Mohammed, Cnops, Vogt, Pareyn and Van Griensven2022; Taye et al. Reference Taye, Melkamu, Tajebe, Ibarra-Meneses, Adane, Atnafu, Adem, Adane, Kassa, Asres, van Griensven, van Henten and Pareyn2024).

The performance of the Loopamp test on crude VL samples indicates that a similar approach could be applied to CL samples, which would simplify sample preparation as outlined in the TPP. Additionally, a number of isothermal amplification devices matching the $2000 price target have now been developed. These could easily be integrated with a telemedicine app that uses AI-based visual lesion analysis as a triage step. This could have a dual effect of improving specificity by ruling out other lesion-causing dermatoses, but also meeting the goal of real-time connectivity, also listed in the TPP. Finally, the test result and lesion photograph could be logged together into a global database, to be regularly updated with patient information about the duration of the disease and responsiveness to treatments. In order to complete the process within the timeframe of the 2030 Roadmap, a focused and concerted effort remains to bring all of these elements together into a well-validated and coherent diagnostic algorithm.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182025101467.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr Zisis Koutsogiannis (University of Edinburgh) and Professor Sammer Yousuf (International Center for Chemistry and Biological Sciences, University of Karachi) for helpful discussions and practical support. ChatGTP (OpenAI) was utilised to guide the structure of the review article, using the query ‘cutaneous leishmaniasis diagnostics review plan’. Neither this nor other AI tools were utilised in the writing of the article.

Author contributions

P.W.D. conceived the review and secured the funding; J.J. wrote the manuscript; P.W.D. and J.J. edited the manuscript.

Financial support

This work was supported by a MRC Impact Acceleration Award (MR/X502947/1; PWD); a studentship to JJ from the EPSRC Molecular Sciences for Medicine Doctoral Training Partnership (EP/S022791/1; PWD); the UKRI - Global Challenges Research Fund, ‘A Global Network for Neglected Tropical Diseases’ (MR/ P027989/1; PWD); The funders had no role in the decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.