Introduction

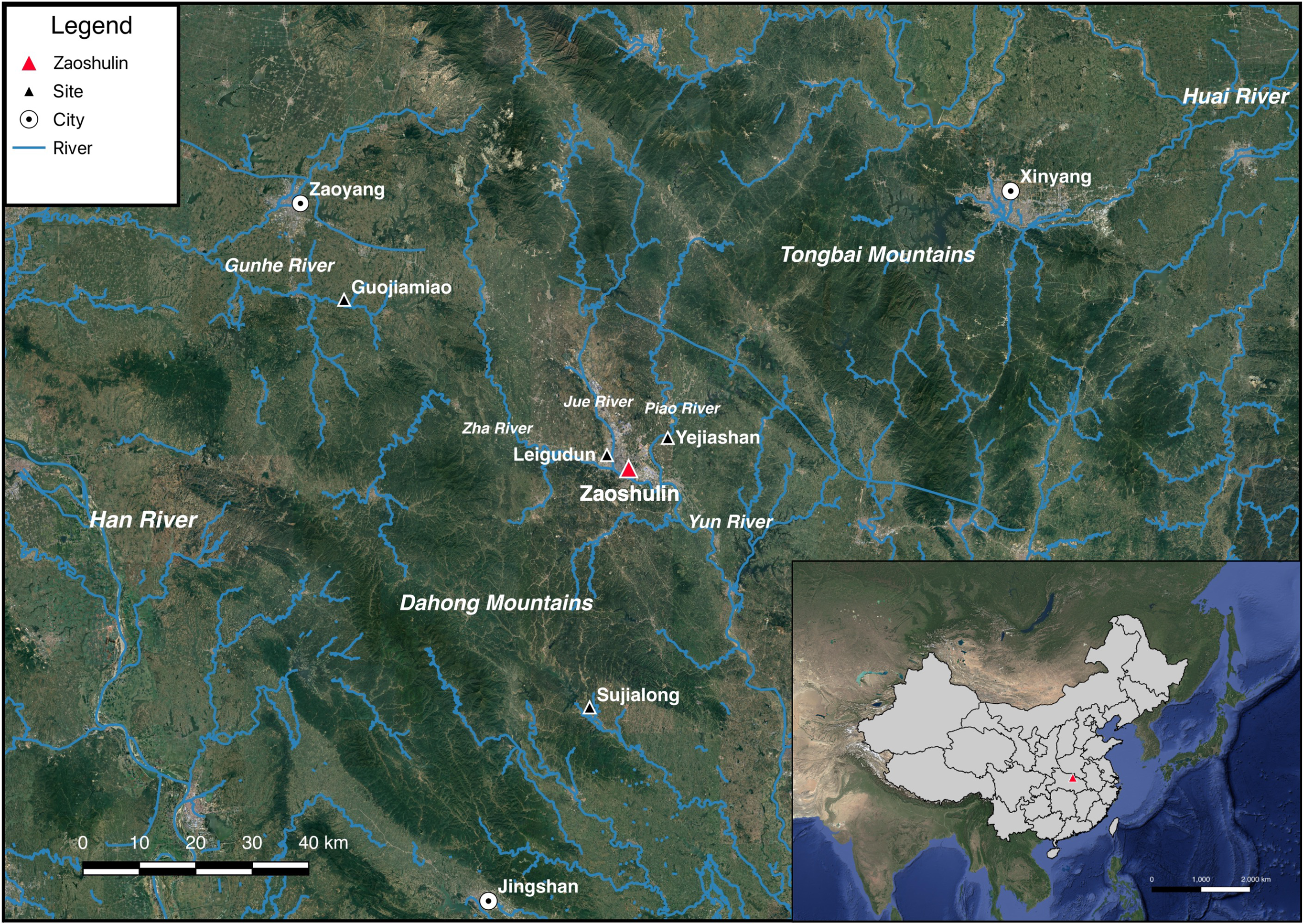

Zeng 曾 (historically known as Sui 隨)Footnote 1 was a Ji 姬-surnamed regional polity established during the Western Zhou period (c. 1046–771 bce).Footnote 2 Situated at the southernmost edge of the Zhou world, it was one of the major powers of the region,Footnote 3 with its capital(s) likely located between Suizhou 隨州 and Zaoyang 棗陽 in present-day Hubei (Map 1).Footnote 4 The prominent status of Zeng had likely continued into the Eastern Zhou period (c. 771–256 bce), as evidenced by its ritual autonomy and the material abundance of its burials.Footnote 5 Despite its prominence, Zeng/Sui only receives sparse and fragmented mention in received texts such as the Zuo zhuan 左傳, in which it often appears in association with other great southern states that are the focus of these accounts.Footnote 6

In recent decades, a substantial number of inscribed Zeng bronzes have been excavated in Suizhou, including two especially important sets of chime bells: the Zeng Gong Qiu bianzhong 曾公![]() 編鐘 (c. 650 bce) and the Zeng Hou Yu bianzhong 曾侯

編鐘 (c. 650 bce) and the Zeng Hou Yu bianzhong 曾侯![]() 編鐘 (c. 500 bce). These bells were likely cast shortly before and after two pivotal events that shaped Zeng–Chu relations during the Eastern Zhou period, namely the Chu conquest of Zeng in 640 bce and the Battle of Boju 柏舉 in 506 bce The inscriptions on these instruments may reflect how Lord Qiu and Marquis Yu actively reinterpreted the past in ways that served their contemporary political needs. As such, they offer a rare glimpse into Zeng’s history from its own perspective and reveal the rhetorical strategies employed by its political actors.

編鐘 (c. 500 bce). These bells were likely cast shortly before and after two pivotal events that shaped Zeng–Chu relations during the Eastern Zhou period, namely the Chu conquest of Zeng in 640 bce and the Battle of Boju 柏舉 in 506 bce The inscriptions on these instruments may reflect how Lord Qiu and Marquis Yu actively reinterpreted the past in ways that served their contemporary political needs. As such, they offer a rare glimpse into Zeng’s history from its own perspective and reveal the rhetorical strategies employed by its political actors.

This article begins with a brief review of the study of chime bell inscriptions and the excavated Zeng bronze bells from Suizhou and Zaoyang, followed by a close analysis of the inscriptions on the Zeng Gong Qiu bianzhong and the Zeng Hou Yu bianzhong. While both inscriptions provide valuable insights into the political situation of Zeng in the Chunqiu 春秋 period (c. 771–453 bce), a detailed analysis of their inscriptional narrativesFootnote 7 also sheds light on the personal responses of their respective donors. This article explores the messages these donors intended to convey and the utilityFootnote 8 these narratives were designed to achieve through the medium of bronze bells and inscriptions. Crafted to address the needs and concerns of the donors, these narratives were crafted into rhetoric that likely played a crucial role in lavish ritual performances. This article argues that while Lord Qiu of Zeng sought to legitimize and celebrate Zeng’s hegemonic status in southern China, Marquis Yu of Zeng aimed to declare loyalty to Chu while simultaneously reasserting Zeng’s autonomous status.

Discussion of Chime Bell Inscriptions

As Martin Kern has argued, bronze inscriptions not only commemorated the glory of their donors and served as a means of communication with ancestral spirits, they also re-enacted an idealized vision of the past and present, while promising the continuation of this legacy into the indefinite future. In turn, the authenticity of the ritual performance legitimized the donor’s status within the lineage and projected an ideal model for future generations to emulate.Footnote 9 Moreover, intended audiences were also fully aware of the inscriptions’ representational nature.Footnote 10 However, the content of bronze inscriptions extends beyond a mere imagined, represented reality constructed through the ritual dialectics of intergenerational emulation and projection. These inscriptions, along with their associated rituals and symbolism, were embedded in and directly engaged with ongoing socio-political processes. The elites who commissioned them were acutely aware of their socio-political circumstances and actively manipulated and adapted inscriptional content to achieve specific strategic outcomes.

Chime bells were frequently used by Zhou aristocrats during rituals and banquets to entertain both ancestral spirits and guests.Footnote 11 As Lothar von Falkenhausen observes, chime bell inscriptions follow a relatively limited set of themes and are often composed in rhyme.Footnote 12 Donors also used these inscriptions to signal political allegiance or assert superior status by commissioning certain types of bronze bells.Footnote 13 However, while many bronze bell inscriptions share similar content, themes, and functions, their intended messages and social effects vary significantly. These differences depended on factors such as materiality, intended audience, production context, and the specific way in which these bells were presented and used in performances. An interdisciplinary approach will therefore be necessary for understanding the meaning and utility of individual bell inscriptions within their historical and ritual contexts.

Moreover, not all chime bell inscriptions were intended for use in ritual performances. Joern Peter Grundmann argues that some inscriptions were never meant to be recited during rituals, as they recount a series of unrelated and non-contemporary events, in which the donor constantly shifts between the roles of addresser and addressee.Footnote 14 In certain chime bell inscriptions such as the Guoji bianzhong 虢季編鐘, the interpenetration of onomatopoeia, standardized rhymes, and phono-thematic structures was designed to re-enact the instrumental quality of ritual performance through the medium of literary text.Footnote 15 As we will discuss below, the Zeng bronze bell inscriptions were likely composed for ritual performances rather than literary re-enactment. Nevertheless, Grundmann’s study remains valuable, as it demonstrates how narrative structure, phonetic elements, and other literary features within bronze inscriptions can offer clues into their intended usage, emphasis, and modes of representation. That said, his narrowly textual approach overlooks the contextual and material dimensions of bronze inscriptions, which are crucial for understanding the broader meaning and affordances of chime bells.

The inscriptions on the surface of chime bells were also an integral part of their visual presence in ritual performances. Huang Ting-chi 黃庭頎 argues that the externalization of bronze inscriptions since the Late Western Zhou reflects an increasing “demand for watching” (觀看需求).Footnote 16 Regional rulers used expensive bronzes to display their power, with bronze inscriptions—like decorative patterns—enhancing the visual and aesthetic appeal of these vessels.Footnote 17 Whether this shift toward externalized inscriptions reflects purely visual concerns remains uncertain, as it might also indicate a change in the way their “sacred message” was transmitted.Footnote 18 Nevertheless, Huang’s work underscores the performative role of the material visuality of Zeng chime bells and their inscriptions, which played a crucial part in shaping both the meaning and effects of their ritual performances.

The Zeng Bronze Bells in Suizhou and Zaoyang

Since the published data on Zeng sites remains incomplete, our observations must be considered preliminary and are based on the available reports (Table 1). The earliest set of bronze bells from Zeng was discovered in Tomb 111 at Yejiashan 葉家山, dated to the late phase of the early Western Zhou period. These bells are capable of producing four notes within their melodic register. Additionally, the presence of a bird mark on their striking surfaces suggests that they served an instrumental function.Footnote 19 However, prior to the Middle Chunqiu period (c. 650–550 bce), bronze bell sets appear to have been rare in Zeng. Chime bells have been excavated only in three Zeng tombs from this time, and none bear inscriptions. Moreover, there appears to be no clear correlation between tomb status and the presence of chime bells. For example, Tomb M30 at Guojiamiao 郭家廟 is classified as a second-level tomb, yet it contained ten niuzhong 紐鐘.Footnote 20 In contrast, Marquis of Zeng, Zhongzi Youfu 仲子斿父 (M1 at Sujialong 蘇家壟) held the highest sumptuary status in terms of ritual bronze sets, but he was interred without any bronze bells.Footnote 21 Earl Qi of Zeng 曾伯桼 (M79 at Sujialong), despite his high-status bronze assemblage, was also buried without bronze bells.Footnote 22 However, it is worth noting that no middle Western Zhou cemeteries of Zeng have yet been discovered, which creates a significant gap in our dataset.

It was not until the Middle Chunqiu period that the top elites of Zeng began regularly adopting inscribed bronze bell sets. These bells were also larger in size and greater in number, significantly expanding the melodic register of each set. Found at Zaoshulin 棗樹林, the chime bells of Zeng Sunshu Zhan 曾孫叔湛 (M81) and Marquis Bao of Zeng 曾侯寶 (M168) are uninscribed or bear only a simple dedicatory statement and prayer. They have been intended for funerary use.Footnote 23 By contrast, the bozhong 鎛鐘 and yongzhong 甬鐘 of Lord Qiu of Zeng (M190), and the bells of Sui Zhong Mi Jia 隨仲嬭加 (M169) are inscribed with long narrative texts. According to their inscriptions, these bells were made for ancestral rituals or banquets.Footnote 24 Other Zeng chime bells with extended inscriptions have been found in the tombs of Marquis Yue(?) of Zeng 曾侯戉(?) (M4) and Marquis Yu of Zeng (M1), rulers of Zeng during the Late Chunqiu period (c. 550–450 bce), at Wenfengta 文峰塔. These bells were likewise made for ancestral worship and feasting ceremonies.Footnote 25 Finally, the chime bells of Marquis Yi of Zeng 曾侯乙 (M1, Leigudun 擂鼓墩)—the largest set of chime bells with the longest inscriptions ever found in Zeng—were specifically produced for entertaining guests during feasts.Footnote 26 It thus appears that long inscriptions were typically reserved for bells intended for ancestral rituals or banquets. Notably, such inscribed bells are found exclusively in the tombs of Zeng’s wealthiest elites, although their production may also have been shaped by the personal histories of their donors, as we will discuss below.

The Chime Bells of Lord Qiu of Zeng

The aristocratic cemetery at Zaoshulin 棗樹林, dated to the Middle Chunqiu period, was excavated in 2018–2019. The massive jia-shaped (甲) burial M190 belonged to Lord Qiu of Zeng 曾公![]() . Although the tomb had been looted multiple times, it still contained hundreds of grave goods, including musical instruments, weapons, chariot fittings, jade accessories, and ritual vessels. In the northwestern quadrant of the tomb, 13 niuzhong bells, four bozhong bells, and 17 yongzhong bells were found.Footnote

27

The inscriptions on the bozhong and yongzhong (i.e., the Zeng Gong Qiu bianzhong)Footnote

28

recount part of Zeng’s history during the Western Zhou period. More importantly, they illustrate how the ruler of Zeng used inscriptional narratives to elevate his status and reinforce diplomatic relationships.

. Although the tomb had been looted multiple times, it still contained hundreds of grave goods, including musical instruments, weapons, chariot fittings, jade accessories, and ritual vessels. In the northwestern quadrant of the tomb, 13 niuzhong bells, four bozhong bells, and 17 yongzhong bells were found.Footnote

27

The inscriptions on the bozhong and yongzhong (i.e., the Zeng Gong Qiu bianzhong)Footnote

28

recount part of Zeng’s history during the Western Zhou period. More importantly, they illustrate how the ruler of Zeng used inscriptional narratives to elevate his status and reinforce diplomatic relationships.

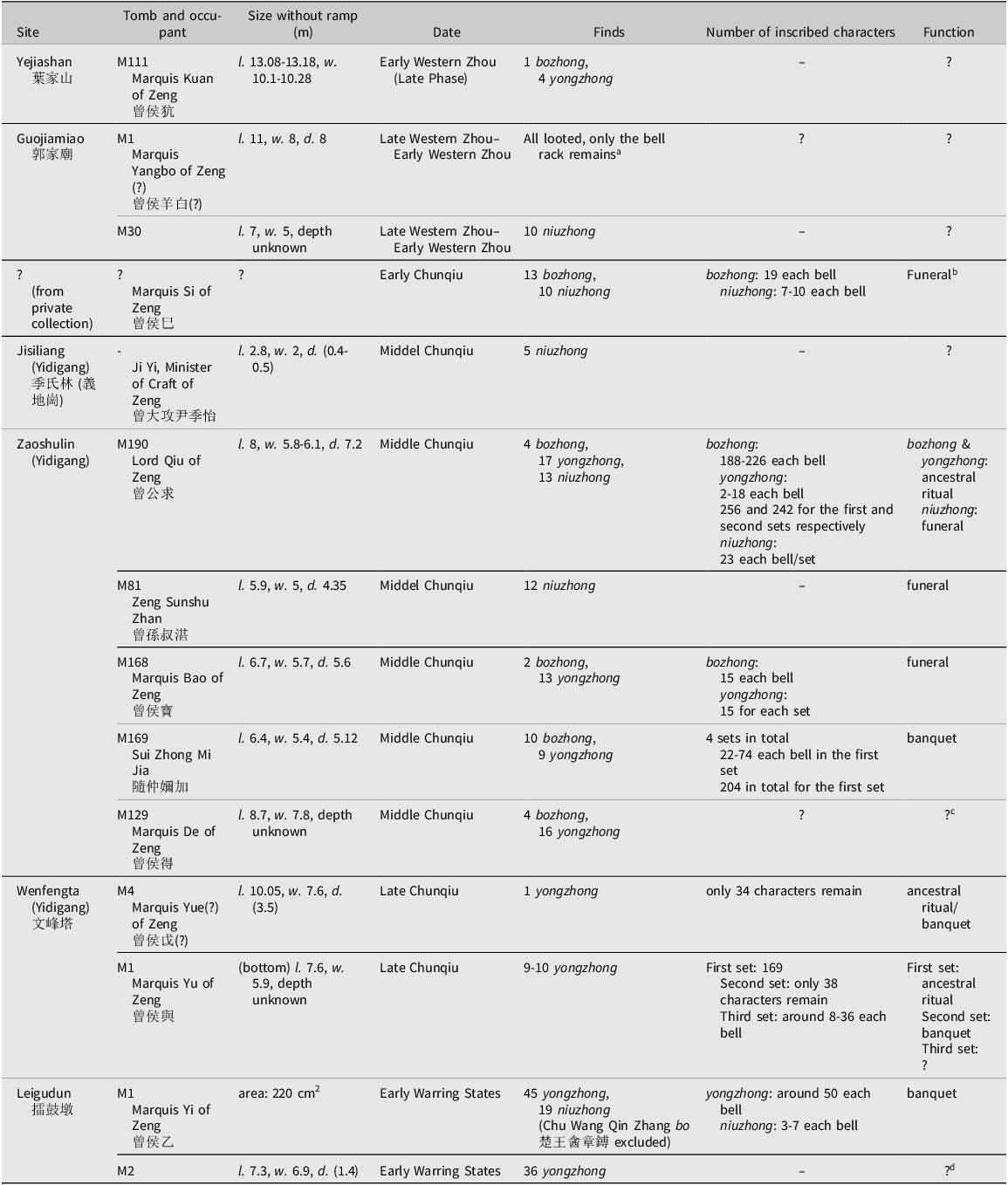

Table 1. Published data on Zeng bronze bells, including site name, tomb size (measured on the ground unless stated otherwise), date, number of bells, number of inscribed characters, and dedicated purpose. For data sources, see notes 19–26, unless specified otherwise

a Fang Qin 方勤, “Guojiamiao Zengguo mudi fajue yu yinyue kaogu” 郭家廟曾國墓地發掘與音樂考古, Yinyue yanjiu 2016.5, 6–8.

b Searched from Zhongyang yanjiuyuan shiyusuo jinwen gongzuoshi, Yin Zhou jinwen ji qingtongqi ziliaoku 殷周金文暨青銅器資料庫. https://w9.ihp.sinica.edu.tw/bronze/.

c Hubei sheng wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo, Suizhou shi bowuguan and Suizhoushi zengduqu kaogudui, “Suizhou Handong Donglu mudi 2017 nian kaogu fajue shouhuo” 隨州漢東東路墓地2017年考古發掘收獲, Jiang Han kaogu 2018.1, 39.

d Hubei sheng bowuguan and Suizhou shi bowuguan, “Hubei Suizhou Leigudun er hao mu fajue jianbao” 湖北隨州擂鼓墩二號墓發掘簡報, Wenwu 1985.1, 17.

In this section, a preliminary translation of the inscription will be provided, followed by a discussion of the text and utility of this inscriptional narrative.

Preliminary Translation of Zeng Gong Qiu bianzhong

The inscription of the Zeng Gong Qiu bianzhong has been divided into three paragraphs according to its thematic structure:Footnote 29

It was in the King’s fifth month,

on the auspicious day of dinghai (day 24),

Lord Qiu of Zeng said:

“In the past, my greatly manifest High Ancestor

was able to assist and act as a counterpart for Kings Wen and Wu of Zhou;

pure was Bo Kuo,

[he] conducted [himself] carefully and possessed de-pattern,Footnote 31

assisting and serving the Deity Above,

[thereby he] continued and received manifold blessings,

and aiding and assisting the Great Zhou.

The Numinous (?) Spirits were sage,

granting [him] great peace.

[He] greatly manifested his numinosity,

and vigorously exerted himself with reverence.

“The king hosted us at the Kang Hall,

summoned [the Chief Governor, and] commanded August Ancestor

to establish [his state] in the southern lands,

guard the southern gate of Cai,

cautiously construct an ancestral hall,Footnote 33

and lead the eastern region of the Han River.

The South [originally] had no boundary,

[but my August Ancestor] crossed the river, attacked Huai barbarians

and reached Fanyang.”

[Qiu] said: “King Zhao [of Zhou] journeyed southward,

[and] issued mandates to Zeng:

‘Fulfill all our decrees/affairs,

and aid and assist the Great Zhou.

[Hereby, I] grant you the yue-axe

to govern the south.’

The glory of Nan Gong,

his great name is well-known;

[he] ascends and descends above and below,

protecting and making his descendants prosper.”

[Qiu] said: “Alas! Worried am I a young Little Son,

I have received no assistance.Footnote 37

My conduct/virtue is my great concern.

[May my ancestors] grant me boundless grace,

making me a match for Heaven’s magnificent grace.

[May] the blessing of Wen and Wu

be fulfilled and celebrated.

[May] blessing and fortune come day by day,

restoring/protecting the boundary of my land.

I have selected auspicious bronze-making copper and smelted hard metal

to make for myself harmonizing bells and ritual vessels for ancestral ritual.

Bright and soothing [they are],

these bells are harmonious and resonant,

to make offering to my August Ancestor Nan Gong,

extending to Lords Huan and Zhuang;

to pray for everlasting life,

extended longevity without limit,

and [may these bells be] forever treasured and used for offering.”

Analysis

The following section will analyze the inscription on compositional, textual, contextual, and material levels.

Text composition

Lord Qiu of Zeng incorporated several new elements into his inscription, yet certain parts of the text were clearly derived from earlier written traditions. Some of these sources are relatively easy to identify. For instance, the couplet “assisted and served the Deity Above, [thereby he] continued and received manifold blessings” (召事上帝,遹褱多福) closely resembles the lines “assisted the Deity Above, and so received manifold blessings” (昭事上帝,聿懷多福) from the poem “Da Ming” 大明 in the Shi jing 詩經.Footnote 38 The donor also drew on other materials, such as the genealogical records of Zeng, which likely incorporated Western Zhou documents. This is evident in certain phrases that betray their Western Zhou provenance.Footnote 39 It is also plausible that the donor deliberately employed archaic Western Zhou inscriptional language—particularly in the first and second paragraphs—in order to lend a sense of authenticity to his narrative and to achieve “the emulation of ancient models.”Footnote 40 This closely aligns with the inscription’s emphasis on the distant ancestors of Zeng as paragons of moral authority—a theme that we will explore further in the discussion that follows.

Nevertheless, the donor also introduced notable variations in his use of the Western Zhou inscriptional language. For example, in the sentence “the king hosted us at the Kang Hall” (王客我于康宮), the verb ke 客 originally meant “to arrive at” in Western Zhou bronze inscriptions. In this instance, here the donor reinterprets it as “to host,” and adds wo 我 as its direct object—likely to make grammatical sense from his own perspective.Footnote 41 As with many other bronze bell inscriptions, the inscription was adapted into a tetrasyllabic format reminiscent of the Hymns 頌 and Elegantiae 雅 in the Shi jing, which were likely performed by a single reciter.Footnote 42 Yet the inscription lacks the regular rhyming pattern, onomatopoeic verses, and phono-thematic correlations between rhyme groups and themes that would allow readers to re-enact ritual performances solely through reciting the inscriptional text.Footnote 43 Its inconsistent rhymes—or more commonly, assonances of finals—more likely served as phono-rhetoric devices that enhanced the rhetorical effect and persuasiveness of the inscriptional narrative.Footnote 44 The repeated use of the first-person pronouns chi/yu 辝/余 (I) and wo 我 (we/I) serve to foreground the donor’s individual agency as a leader of Zeng and to enhance the assertiveness of his speech.Footnote 45

Genealogy, command, and yue-axe

The text of the Zeng Gong Qiu bianzhong can be divided into three thematic paragraphs: the first recounts the accomplishments of his High Ancestor (i.e., Bo Kuo),Footnote 46 the second highlights the achievements of the August Ancestor (i.e., Nan Gong),Footnote 47 and the final paragraph functions as a series of “benedictory statements” (guci 嘏辭).

In the first paragraph, the donor aligns his High Ancestor with Kings Wen and Wu—the founding fathers of the Zhou dynasty. This likely reflects a desire to affiliate with the Ji-surnamed aristocratic network, which continued to hold political dominance during the Middle Chunqiu period, by invoking the collective memory of the foundational moment that defined Zhou identity.Footnote 48 However, the phrase “assisted the Deity Above” (召事上帝) is notable for its ritual transgression, as direct association with the Deity Above and Heaven had traditionally been reserved for Zhou kings. Nonetheless, by this period, many regional rulers had already begun to appropriate this sacred connection.Footnote 49 The reference to Kings Wen and Wu in this inscription more likely serves as a chronological marker that situates the achievement of Bo Kuo within his politico-historical background. In this retelling, Bo Kuo effectively replaces the Zhou founding kings as the flawless intermediary between the Deity Above and the human realm. Therefore, Lord Qiu’s narrative of Zeng history was not intended to resonate with broader Ji-surnamed communities, but rather an effort to reaffirm—and possibly recast—Zeng’s own collective memory by emphasizing the moral superiority and numinous character of its founding ancestor, thus demonstrating the exceptional origin of the Zeng polity.

This interpretation is further supported by the second paragraph, which recounts the ming 命 (command or mandate) received by Qiu’s ancestors from Zhou kings to govern “the eastern region of the Han River.” During the Western Zhou period, ming referred to formal ceremonious speech acts issued by superiors—usually kings—to confer rewards upon the addressees and affirm the transmission of ancestral de-pattern.Footnote 50 Lord Qiu of Zeng has likely appropriated the concept of ming as a source of authority. According to the inscription, his August Ancestor was “commanded” (命) by King Zhao of Zhou to “aid and assist the Great Zhou” (左右有周). The verb “to aid and assist” (左右) usually denoted an essential role played by certain individuals in aiding the Zhou kings or other prominent leaders.Footnote 51 However, Lord Qiu repeatedly states that his ancestors assisted “the Great Zhou” on the left and the right, rather than any specific individuals. In the second paragraph, Nan Gong has even been explicitly commanded by King Zhao of Zhou to assist the “Great Zhou” in order to “fulfil all [their] decrees/affairs,” implying that the responsibility of governing the Zhou world was shared between the king and Qiu’s ancestors. Through his choice of wording in recounting the history of his ancestors—particularly the use of the term ming—Qiu elevates his ancestors to a status closely aligned with, if not equivalent to, the Zhou kings. These elements emphasize Zeng’s historical ties to royal authority and its ongoing obligation to “the Great Zhou,” thereby legitimizing its political dominance in the south.

The donor continues by stating that King Zhao “granted the yue-axe” to his ancestor to “govern the south.” Yue-axe was a type of ritual weapons that had symbolized royal authority since the Shang dynasty.Footnote

52

In received texts such as the “Mushi” 牧誓 and “Guming” 顧命 passages of the Shang shu 尚書, the yue-axe often featured in idealized accounts of Western Zhou ceremonies. Although these were likely composed during the Eastern Zhou period, the presence of the yue-axe in these idealized accounts of royal ceremonies demonstrates the semiotic connection of yue-axe with the notion of royalty and authority during this period—a symbolism that Lord Qiu of Zeng adopted to assert his authority.Footnote

53

Earl Qi of Zeng 曾伯陭, a predecessor of Qiu buried at Guojiamiao, also commissioned a ritual yue-axe with inscriptions: “Earl Qi of Zeng casts this axe. [It] serves [as] the symbol of law/model for the people. It is not used for punishment, [but] for governing the people” (曾伯陭鑄戚鉞,用為民![]() ,非歷殹井(刑),用為民政.Footnote

54

This demonstrates that the symbolical connection between the yue-axe and the exclusive right of governance had already been established in the Zeng state well before the Middle Chunqiu period.

,非歷殹井(刑),用為民政.Footnote

54

This demonstrates that the symbolical connection between the yue-axe and the exclusive right of governance had already been established in the Zeng state well before the Middle Chunqiu period.

Thus, the granting of ming and the yue-axe by the Zhou kings, as described in Lord Qiu’s inscription, was symbolically tantamount to conferring upon Zeng the royally sanctioned right to rule the south. Regardless of the historical accuracy of his claims, Lord Qiu of Zeng strategically adopted widely circulated concepts and representations of power and sovereignty to reassert Zeng’s independence and superiority.

Historical context

The third paragraph of the inscription clearly states that the Zeng Gong Qiu bianzhong was intended for use in ancestral rituals. However, its historical context suggests that the inscriptional narrative was more than a mere ritual liturgy. The calendrical notation on the bells allows them to be dated to 646 bce, and their style also places them in the early phase of the Middle Chunqiu period.Footnote 55 According to the Zuo zhuan, during the reign of King Wu of Chu 楚武王 (r. 704–690 bce), Chu and Zeng had at least three military confrontations, with neither state gaining a decisive advantage.Footnote 56 During the reign of King Cheng of Chu 楚成王 (r. 671–626 bce), Chu sought to expand northward. After being repelled by an alliance led by Qi 齊 in 656 bce, Chu reached a rapprochement with Qi and shifted its focus southward.Footnote 57 In 655 bce, Chu conquered the Xian 弦 state near present-day Huangchuan 潢川.Footnote 58 In 649 bce, it commenced hostilities against the Huang 黃 state, which had previously offered refuge to the Hereditary Prince of Xian 弦子 and refused to pay tribute to Chu. One year later, Chu had subjugated Huang.Footnote 59 Both Xian and Huang were allies to Zeng, and were situated just around 180 km east to Suizhou.Footnote 60 By this point, Zeng’s legitimacy and sovereignty had been challenged and weakened by Chu, as its southern allies gradually fell one after another, and the expansionist and diplomatic strategies of King Cheng of Chu led to Zeng’s increasing geopolitical isolation. The donor is poignantly aware of his precarious situation, as evidenced by the statement, “I have received no assistance” in the inscription.

It seems that the inscriptional narrative was likely intended to achieve two goals. First, the donor aimed to emphasize the relevance and importance of Zeng in the south. A substantial portion of the inscription is devoted to recounting the achievements of High and August Ancestors of Zeng. It was likely intended to remind the audiences of Zeng’s historical role in protecting other southern states and “lead[ing] the eastern region of the Han River.” By presenting a glorious descent closely linked to the Zhou royal house, the donor may have sought to reaffirm Zeng’s eminence and continued relevance, positioning himself as a hegemonic figure.Footnote 61 Second, by retelling King Zhao’s campaign to the south—a historical episode exemplifying royal hostility toward ChuFootnote 62 —the donor could integrate his lineage’s genealogy into the anti-Chu narrative. This incorporation of an anti-Chu element might have been a strategic attempt to gain the support of smaller southern states that either shared this ideology or were themselves under threat from Chu. The allegiance of these states was crucial for the donor in his course to “restore/protect the boundary of [his] land.” His idealized version of history—in which every southern state between the Han River and Fanyang was safeguarded and stabilized under the leadership of Zeng—can also be seen as an alternative vision of a Zeng-centered political order opposing to the current aggressive, expansionist regime of Chu. Thus, the inscriptional narrative was designed to present him as the legitimate leader and protector of southern states, in order to rally support against Chu.

Materiality

The inscriptional narrative was crafted to appeal to its audience audibly, just as the bells were designed to be visually appealing. The primary focus of the Zeng Gong Qiu bianzhong is its four massive bozhong (h 50.5–58.5 cm, w 18–26.2 cm), each adorned with meticulously crafted openwork dragon-motif spines on all four sides (Figure 1).Footnote 63 This design first appeared in northern China, as seen in the Ke bo 克鎛 (JC209) and Qin Gong zhong 秦公鐘 (JC267), which all date earlier than the Middle Chunqiu period. Bronze bells with a similar design were also found in the Xǔ 許 state during the Middle Chunqiu period.Footnote 64 However, the Zeng Gong Qiu bianzhong was likely the only set of bronze bells in southern China to adopt this form. The display of these elaborate, non-local-style bells during ritual performances may have implicitly emphasized the connections of Zeng with northern polities—probably appealing to those who would like to distance themselves from the southern culture represented by Chu—but it would have also been an unambiguous statement of the donor’s wealth and power.

Figure 1. Bozhong M190:32, h 55.3, w 28.3 cm. Image from Hubei sheng wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo et al., “Zaoshulin Chunqiu Zengguo guizu mudi,” 82, fig. 14.

Recent chemical analysis of surface residues on a yongzhong bell from the Zeng Gong Qiu bianzhong (i.e., M190:234) reveals that its recesses and inscriptions were originally inlaid with quartz.Footnote 65 While the whitish hue of quartz might not have enhanced the legibility of the inscription on the glistening surface of the yongzhong,Footnote 66 it would certainly have added an extra layer of opulence to the bells. The combined use of yongzhong and bozhong likely served as a status marker, as such pairings became popular among powerful regional rulers during the Chunqiu period.Footnote 67 The recitation of the inscriptional narrative was a central element of the ritual performance, in which the audience—including Zeng lineage members and representatives from smaller southern states—would have been exposed to the ornate speech and visual grandeur orchestrated by Lord Qiu of Zeng. Through this orchestration of visual display, inflective recitation, and musical performance, Lord Qiu asserted the superiority of Zeng and garnered political support from neighboring states.

In sum, this inscriptional narrative was designed to proclaim Zeng’s superiority among southern states and secure their loyalty. According to the Zuo zhuan, in 641 bce, Chu formed an alliance with Qi and other northern states. The following year, Zeng led a coalition of southern states in a war against Chu, but their forces were overwhelmed by the Chu army.Footnote 68 Afterward, King of Chu, Xiong Ling 楚王熊 (i.e., King Cheng of Chu) gave his younger sister Mi Yu 嬭漁 to Lord Qiu in marriage.Footnote 69 Qiu later commissioned a new set of chime bells (niuzhong) for his own funeral, which were neatly placed in the northwestern quadrant of his tomb. In contrast, the Zeng Gong Qiu bianzhong (bozhong and yongzhong) was found haphazardly piled in a corner, suggesting this bell set was not part of the orderly funerary assemblage.Footnote 70 Following Qiu’s marriage, Zeng maintained close ties with the Chu royal house: Mi Jia 嬭加, a daughter of a Chu king, married Marquis Bao of Zeng—likely the successor of Qiu.Footnote 71

The Chime Bells of Marquis Yu of ZengFootnote 72

Following Lord Qiu of Zeng, the next two generations of rulers—Marquis Bao and Marquis De of Zeng—were also buried at Zaoshulin. But after the Middle Chunqiu period, the Wenfengta 文峰塔 cemetery, located around one kilometer south to Zaoshulin, had become the primary burial ground for the Zeng ruling elites. Excavated in 2009, the Wenfengta cemetery dates to the Late Chunqiu period. Tomb M1 (7.1 m × 5.9 m; depth undetermined) belonged to Marquis Yu of Zeng 曾侯![]() . Hundreds of grave goods were buried with him, including at least three sets of yongzhong. By the time of excavation, the tomb had suffered severe damage and extensive looting. Ten bronze bells were found in the tomb, some severely eroded and fragmented, though their inscriptions were largely intact.Footnote

73

The inscription of the first set of yongzhong (the Zeng Hou Yu bianzhong) shares structural similarities with the Zeng Gong Qiu bianzhong, but differs considerably in both content and production context. Significantly, the statements of Marquis Yu made in his bell inscriptions are generally more self-congratulatory and place greater emphasis on personal accomplishments than those of Lord Qiu. Although the Zeng Hou Yu bianzhong has already received substantial scholarly attention, a comparative analysis of the two sets of chime bells can offer new insights into the aims and utility of this inscriptional narrative.

. Hundreds of grave goods were buried with him, including at least three sets of yongzhong. By the time of excavation, the tomb had suffered severe damage and extensive looting. Ten bronze bells were found in the tomb, some severely eroded and fragmented, though their inscriptions were largely intact.Footnote

73

The inscription of the first set of yongzhong (the Zeng Hou Yu bianzhong) shares structural similarities with the Zeng Gong Qiu bianzhong, but differs considerably in both content and production context. Significantly, the statements of Marquis Yu made in his bell inscriptions are generally more self-congratulatory and place greater emphasis on personal accomplishments than those of Lord Qiu. Although the Zeng Hou Yu bianzhong has already received substantial scholarly attention, a comparative analysis of the two sets of chime bells can offer new insights into the aims and utility of this inscriptional narrative.

Preliminary translation of the Zeng Hou Yu bianzhongFootnote 74

It was the king’s first month,

the auspicious day, jiawu (day 31).

Marquis Yu of Zeng said:

“Bo Kuo, our Ancestor on High,

aided and assisted Kings Wen and Wu

to attain the Yin’s Mandate,

and consoled and pacified all beneath the Heaven.

The king passed on the command to Nan Gong,

to found his establishment at the confluence of the river/land afar,Footnote 75

to rule and govern the Yi-barbarians of Huai River,

and keep watch over the Yangtze and Xia Rivers.”

“Since the House of Zhou has already declined,

we mediate with the proud Chu.

Wu has got hold of the multitudes to wreak havoc,

campaigned westward, attacked southward,

and caused [chaos] in Chu.

The state of Jing (i.e., Chu) had been weakened,

[and] the Mandate of Heaven was about to be erroneously transferred.

Solemn was the Marquis of Zeng,

great was his intelligence,

[he] personally gained military achievements,

and the Mandate of Chu is now secured.

[He] stabilized anew the King of Chu,

[such was] the numinous power of the Marquis of Zeng.”

Dignified is the Marquis of Zeng,

strong, courageous, and cautious,

respectfully and reverently [he] purifies himself for covenants;

[being] the model of conquest and martial virtue,

and mollifies and puts to order the four quarters.

I consolidate anew our alliance with Chu,

and restore/protect the territorial integrity of Zeng.

I select my auspicious bronze-making metal,

and make these sacrificial vessels by myself.

The harmonious bells ring brightly,

employed in sacrifices to my glorious ancestors,

to pray for longevity,

[and] the prolongation of our Great Mandate,

[to pray] the pure de-pattern descend,

and [may] we cherish and protect it for ten thousand generations.Footnote 78

Analysis

Text composition

The figures Bo Kuo and Nan Gong mentioned in the opening paragraph of the Zeng Hou Yu bianzhong correspond to “High Ancestor” and “August Ancestor” referenced in the Zeng Gong Qiu bianzhong. While the donors of both inscriptions likely draw from the same aristocratic genealogy, they paraphrase it in distinct ways.Footnote 79 In the Zeng Hou Yu bianzhong, the achievements of Bo Kuo and Nan Gong are condensed into a single paragraph, retaining only the descriptive elements. The mandate from King Zhao of Zhou—an element in the story of Nan Gong—is omitted. Instead, Bo Kuo is directly associated with the Conquest of Shang, the event that led to the founding of Zhou dynasty. Following the first paragraph, a significant portion of the inscription is devoted to extolling the merits of Marquis Yu of Zeng in pulling Chu back from the brink of collapse. This emphasis on contemporary history and personal achievements stands in contrast with the Zeng Gong Qiu bianzhong, which mainly focuses on venerating the distant ancestors of Zeng and contains no self-glorifying statements.

Additionally, the language of the Zeng Hou Yu bianzhong is notably less antique than that of Zeng Gong Qiu bianzhong, as it incorporates a greater number of linguistic elements from the Chunqiu bronze inscriptional glossary.Footnote 80 While this difference is certainly attributable to the later date of composition, it may also suggest that Marquis Yu did not feel compelled to emulate the inscriptional style of the Western Zhou period. Furthermore, rhymes and assonances appear more frequently and systematically in the Zeng Hou Yu bianzhong, indicating a stricter emphasis on phonetic consistency in his inscription—particularly in sections that recount the accomplishments and exceptional qualities of himself and his ancestors. It likely served to emphasize both his own personal brilliance and the brilliance of his lineage during ritual performances of the text. As will be discussed later, self-glorification plays a prominent role in the Zeng Hou Yu bianzhong.

Mandate of heaven and self-glorification

The first paragraph of the Zeng Hou Yu bianzhong briefly recounts the achievements of Bo Kuo and Nan Gong, while the second highlights the accomplishments of Marquis Yu of Zeng. The final paragraph emphasizes his admirable qualities and concludes with a succinct guci.

As discussed earlier, the genealogy may have been intended to showcase Marquis Yu’s prestigious descent, but he seems more interested in celebrating his own brilliance—a prevailing trend during the Middle to Late Chunqiu period.Footnote 81 The donor may also have recognized the need to justify Zeng’s political realignment, which marked a departure from its traditional allegiance to Zhou. He likely found the concept of tianming 天命 (“Mandate of Heaven”) useful for this purpose. During the Eastern Zhou period, the meaning of tianming or ming evolved from signifying the universal rule over the Zhou world to denoting regional dominance or independent sovereignty. Some regional rulers, including Marquis Yu of Zeng, deliberately blurred this distinction. Notably, in the second paragraph, Marquis Yu states that “the House of Zhou has already declined” and “the mandate of Chu is now secured,” suggesting that Zhou was no longer the recipient of the ming—much like Shang after its conquest by Zhou. Yu thus justifies his support for the Chu state, where the “ming” now presumably resided in his time, though its precise meaning is intentionally left ambiguous.Footnote 82

Although Marquis Yu explicitly claims that the ming had been transferred to Chu, he does not display a subservient attitude toward it. This stands in contrast to his recent ancestor Marquis Yue(?) of Zeng 曾侯戉(?), who pledged in his bell inscription to “aid and assist the Chu king” (左右楚王).Footnote 83 Instead, Marquis Yu’s inscriptional narrative reads more like the speech of a hegemon. A parallel can be drawn with the Jin Gong pen 晉公盆 (JC10342), likely cast during the Middle Chunqiu period. The phrases in its inscription, “coordinate and order ten thousand states” (協燮萬邦) and “devoutly and respectfully made covenant and ritual” (虔恭盟祀),Footnote 84 bear a striking resemblance to certain phrases in the Zeng Hou Yu bianzhong, including “mollify and order four quarters” (懷燮四方) and “respectfully and reverently purifies for covenant” (恭寅齋盟). Through these phrases, Marquis Yu conveys an expectation that his “alliance with Chu” would be maintained—not as a subordinate relationship, but as one in which Zeng remained an autonomous polity that could “mollify and order” other polities, while its own covenant with other states was respected. In other words, Yu demanded an elevated status for Zeng—one that was not beneath “the proud Chu.” This interpretation is further supported by the conclusion of his inscription, where Yu expresses his wish to prolong the “Great Mandate”—likely referring to his independent right to rule.Footnote 85 Here, Marquis Yu positions Zeng as one of the recipients of ming, alongside Chu and other hegemonic states.

Additionally, Marquis Yu of Zeng significantly shortens the guci in favor of expanding the accounts of his personal merits. In these accounts, he primarily emphasizes his martial prowess, as seen in phrases such as “personally attain[ing] military achievements” and “[being] the model of conquest and martial virtue.” However, a common theme in Zeng bronze inscriptions—the mercy and benevolence of rulers—is entirely absent in the Zeng Hou Yu bianzhong.Footnote 86 This emphasis on martial qualities was likely intentional, as Marquis Yu had secured a triumphant victory that led to the restoration or peace of “the territorial integrity of Zeng”—a goal for which Lord Qiu of Zeng had previously sought ancestral blessing. It could also reflect Marquis Yu’s desire to establish himself as an exemplary, militarily accomplished figure who stood out from the models set by his recent ancestors. On a textual level, this proud—if not overtly self-congratulatory—inscription demonstrates that the donor demanded a higher status both for Zeng in interstate politics and for himself within the lineage.

Historical context

The calendrical notation in the Zeng Hou Yu bianzhong dates it to 497 bce; the style of the chime bells and other bronzes in his tomb (M1) also places it within the middle phase of Late Chunqiu period.Footnote 87 The battle referenced in the inscription likely refers to the Wu invasion in 506 bce. According to the Zuo zhuan, after Helü 闔閭 ascended the throne as the King of Wu (r. 514–496 bce), he soon launched hostilities against neighboring states.Footnote 88 In 512 bce, Wu eliminated Xú 徐 after it failed to intercept Helü’s cousins, who were also legitimate contenders for his throne. His exiled cousins later fled to Chu, where they were enfeoffed by King Zhao of Chu 楚昭王 (r. 515–489 bce). This event motivated Helü to accept Wu Zixu’s 伍子胥 (d. 484 bce) proposal to attack Chu.Footnote 89 The Battle of Boju in 506 bce was a turning point in the conflict between Wu and Chu, as Wu’s forces devastated Chu to the extent that its capital (郢 Ying) was plundered. The Zuo zhuan records that King Zhao of Chu fled to Zeng, which, after consulting divination, refused to hand King Zhao of Chu over to Wu.Footnote 90 However, the narrative in the Zeng Hou Yu bianzhong suggests that Zeng played a more active role in the war. In either case, Zeng proved itself to be an indispensable ally in preserving Chu’s Mandate of Heaven, which was frequently contested by rival powers. Meanwhile, by declaring that “the House of Zhou had already declined,” Zeng may have also sought to extricate itself from the former obligations to Zhou while severing any perceived ties to Wu—a self-proclaimed Ji-surnamed state.Footnote 91

However, Zeng did not entirely abandon its Zhou heritage—namely its genealogy—but rather subtly adapted it. In Marquis Yu’s narrative, Bo Kuo, a senior minister who served Kings Wen and Wu, is portrayed as a key participant in the Conquest of Shang. Meanwhile, Nan Gong, previously depicted as an overseer and governor of the Huai Barbarians, no longer receives the royal mandate and yue-axe from King Zhao of Zhou in Marquis Yu’s narrative. This omission was likely a strategic decision aimed at maintaining amity with Chu, as King Zhao’s southern campaign had historically positioned Zeng as an adversary of Chu. The royal mandate and yue-axe from King Zhao also symbolized leadership over the south—authority long eroded by Chu and other southern powers. Nevertheless, Marquis Yu’s retelling of Zeng history does more than merely present a sanitized version of his genealogy, as it also affirms his embodiment of his ancestral legacy. Like Bo Kuo, who courageously overturned the Shang and consolidated Zhou’s Mandate of Heaven, Yu led his army to strike down enemies and restore the Mandate of Chu. Similarly, just as Nan Gong had been entrusted with governing and guarding against the barbarians of Huai, Yu repelled the Wu army—inhabitants of the Huai region who had threatened the Chu-centered political order. Through this narrative, he positioned himself as the equal of his illustrious forebears.

Notably, his inscriptional narrative is a carefully crafted political statement that both acknowledges the leading role of Chu in the south and simultaneously asserts that Zeng was by no means inferior to Chu. In the Zeng Hou Yu bianzhong, although Marquis Yu never directly challenges the authority of Chu, he repeatedly and proudly reminds the audiences of his own magnificence—as exemplified in the couplet, “[he] stabilized anew the King of Chu, [such] was the numinous power of Marquis of Zeng.” He casts himself as the one who repelled the Wu army and rescued the embattled and ill-fated King of Chu along with Chu’s mandate—just as earlier Zeng rulers had once supported the Zhou kings. Through this narrative, the donor establishes himself as both the inheritor of the ancestral de-pattern and a powerful defender essential of Chu’s current political dominance.

Materiality

The monumental size of Marquis Yu’s chime bells—especially the largest one (M1:1), measuring 112.6 cm in height and 49.2 cm in width, comparable to those commissioned by members of royal familiesFootnote 92 —served as a powerful display of self-aggrandizement. Their well-polished and seamless surfaces bear slim, elegantly elongated inscriptions, which further accentuate the grandiose display.Footnote 93 Additionally, the intricate decoration on the bells’ striking surfaces—composed of numerous interwoven little panchi 蟠螭 (hornless-dragon) forming a raised panchi-pattern (Figure 2)Footnote 94 —likely evoked a distinctive visual-haptic sensation among the audiences, and drew their attention to the exquisite craftsmanship of the bells. This particular panchi-pattern, along with the octagonal shank, also appears on the Zeng Hou Yue(?) bianzhong and bells attributed to other prominent elites, such as the Wangsun Gao bianzhong 王孫誥編鐘 and the Wangsun Yizhe zhong 王孫遺者鐘 (JC261).Footnote 95 Associated with the highest-ranking aristocrats, this localized design would have been visually recognizable to audiences in the southern states. Both the material properties of these bells and their inscriptions were integral to the lavish performance Marquis Yu devised, through which he asserted his authority and delivered his diplomatic and self-panegyric messages to his audiences from southern China.

Figure 2. Yongzhong M1:1, h 112.6, w 49.2 cm. Image from: Hubei sheng wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo and Suizhou shi bowuguan, “Wenfengta M1 (Zeng hou Yu mu),” 15, fig. 22.

In sum, the inscriptional narrative of Zeng Hou Yu bianzhong was carefully crafted to affirm Zeng’s loyalty to Chu while simultaneously asserting the elevated status of both the state and the donor within the Chu-centered political order. Evidence suggests that Zeng retained a degree of autonomy and prominence within Chu’s sphere of influence well into the Warring States period (c. 453–221 bce), as exemplified in the lavish burial of Marquis Yi of Zeng 曾侯乙 (M1 at Leigudun). Whereas many of his grave goods were gifts from Chu dignitaries and regional rulers from both nearby and distant states,Footnote 96 King Hui of Chu 楚惠王 (r. 488–432 bce) also commissioned a bronze bell to commemorate Marquis Yi, which was placed at the very center of Yi’s tomb.Footnote 97

Conclusion

The inscriptional narratives of the Zeng Gong Qiu bianzhong and Zeng Hou Yu bianzhong exemplify the trend of individualized bronze inscriptions during the Eastern Zhou period. The donors of these two chime bells strategically adapted content, language, and formatting from various source materials to tailor narratives that effectively conveyed their political stances and influenced other political actors. By examining the nuances and similarities, additions and omissions, as well as consistencies and discrepancies within these narratives, we gain insight into Zeng’s political history from its own vantage point and the strategic maneuvering of its rulers.

Both Zeng leaders modified their inscriptional narratives to serve their interests, by adding—if not fabricating—and omitting historical details to create cohesive narratives. Lord Qiu of Zeng emphasized Zeng’s historical role in the south, in order to assert its superiority within the southern Zhou sphere and solidify allegiance from smaller states. Marquis Yu of Zeng, by incorporating his achievement of saving Chu into his narrative, simultaneously declared loyalty to Chu and reaffirmed both his own prominence and Zeng’s autonomy within Chu’s domain. These narratives were crafted as elaborate speeches integral to ritual performances, through which their donors’ messages were clearly communicated. While it remains uncertain how these bronze bells were used in ritual ceremonies, their material grandeur suggests the splendor in the Zeng’s ancestral temple and allows us to imagine the sensory experience of rituals involving these chime bells as the narratives inscribed upon them were performed.

As products of their time, these bell sets reflect broader historical trends during the Middle-Late Chunqiu period. In the Zeng Gong Qiu bianzhong, Lord Qiu recounts the glorious feats of his ancestors—a theme commonly found among his contemporaries—demonstrating the enduring, and even intensified, emphasis on the lineage’s founding history in a period when great powers sought to justify their hegemony through ritual, rhetorical, and military means. By contrast, in the Zeng Hou Yu bianzhong, Marquis Yu highlights his personal achievements rather than those of his ancestors, suggesting a trend of individualization and self-glorification at the end of the Chunqiu period, when interstate warfare and conquest become more frequent and intense. Nonetheless, the emulation of ancestral de-pattern remains the main strand that connects these two inscriptions. Different Zeng rulers, however, seem to have understood its embodiment in different ways: while Lord Qiu demonstrates his succession of de by consecrating and retelling the history of the founding ancestors, Marquis Yu emphasizes his political actions that seemingly re-enact the epoch-making deeds of his ancestors, presenting him as the living incarnation of ancestral de-pattern.

However, there is no definitive evidence that these inscriptional narratives were actually performed in their intended ritual contexts. Instead, the bells, repurposed as grave goods, came to signify the status of the deceased and allowed for their earthly ritual musical performance to continue in the afterlife. While we can infer their intended utility, their exact historical influence remains unknown. This article represents a tentative attempt to integrate materiality and inscription analysis, though its focus on chime bell inscriptions and their utility limits its scope and largely overlooks other aspects. Further research must incorporate additional historical, archaeological, and archaeometric data to better understand the complex relations these bells once fostered between their donors, audiences, and other objects.