Since the late 1980s, ideas about the “new father” – an engaged father who is actively involved in his children’s daily lives – have been a recurring theme in public debates and academic literature in Western democracies (Dermott Reference Dermott2008; Dermott and Miller Reference Dermott and Miller2015; Kangas and Lämäs Reference Kangas, Lämsä and Jyrkinen2019; Rane and McBride Reference Rane and McBride2000). However, in most parts of the world, mothers remain at the center of parenting policies, although some countries, notably the Scandinavian ones, deviate by allocating a significant share of parental leave days to fathers, thus striving to realize an active fatherhood role in practice (Hyland and Shen Reference Hyland and Shen2022; Kern and Lecerf Reference Kern and Lecerf2025).

In Sweden, often considered a forerunner in matters of gender equality, parental leave policies became gender-neutral in 1974, meaning that Swedish fathers have, for a comparatively long period of time, had the same rights as mothers to take time off work to care for young children (Cedstrand Reference Cedstrand2011). Since few men took advantage of this opportunity in the 1970s and 1980s, a policy of 30 non-transferable days, a so-called “daddy month,” was introduced in 1995 in Sweden and later extended to 60 days in 2002 and to 90 days in 2016. Over time, Swedish fathers’ use of parental leave has increased but at a slower pace than anticipated (Ekberg et al. Reference Ekberg, Eriksson and Friebel2013).Footnote 1 In this sense, policy initiatives that encourage an active fatherhood role may not be accompanied by equivalent changes in social norms and ideals surrounding fathers. Thus, this study investigates depictions of fatherhood roles in Swedish parliamentary documents over time with the aim to determine whether a discursive shift has actually taken place in Sweden, making an active and engaged fatherhood role more prominent than a traditional passive breadwinner fatherhood role of the past.

This study differs from most previous research on fatherhood roles in that it uses Large Language Models (LLMs), which facilitate the analysis of very large amounts of text. In the forthcoming empirical section, we examine all parliamentary documents in Sweden from 1993 to 2021, including policy documents outside the areas of family and gender equality policy, which are more traditionally studied by scholars analyzing fatherhood roles and norm change (e.g., Andreasson et al. Reference Andreasson, Tarrant, Johansson and Ladlow2023; Cedstrand Reference Cedstrand2011; Fransson et al. Reference Fransson, Hjern and Bergström2018; Johansson Reference Johansson2011). The rationale for our study is that policies like non-transferable days in parental leave, despite being based on economic sanctions such as loss of payment if fathers do not take active part, largely are meant to change people’s mindsets and ideas on parenthood (Cedstrand Reference Cedstrand2011). For norm change to occur, however, people need triggers that update their perceptions of what is acceptable behavior. As Valentim (Reference Valentim, Grasso and Giugni2023) argues, institutional “elite” signaling is a mechanism through which people’s updates can take place. Following this line of reasoning, our theoretical proposition is that norm change in society is more likely to occur when members of a political institution like a national parliament continuously send signals in the direction of the views expressed in the decisions made by the institution.

To determine the types of discursive shifts taking place around fatherhood, one must evaluate the ideal of the “new father” alongside other potential fatherhood roles, such as the traditional breadwinner or abusive, dominant father which may also be present in texts such as policy documents. Using LLMs, we provide a more complete overview of positive and negative portrayals of fatherhood roles in parliamentary documents than what has been presented in research to date (e.g., Andreasson et al. Reference Andreasson, Tarrant, Johansson and Ladlow2023; Cedstrand Reference Cedstrand2011). Contrary to our expectations of a prominent role for the “new father” ideal, one of our main findings is that, although an active, positive fatherhood role – one that Swedish policymakers seek to encourage – is dominant in our material, an active, negative fatherhood role – one that Swedish policymakers seek to restrict – is also present to a significant extent. Furthermore, the relative strength of these two very different roles fluctuates, and over time, a negative, abusive fatherhood role becomes more visible in the examined material.

In addition to the mapping of fatherhood roles by LLMs, we relate the frequency of different depictions of fathers to decision-making with bearing on fathers’ behavior and to data on developments in father’s use of parental leave. The inclusion of such different materials makes it possible for us to show that an active positive fatherhood role is most frequent around 2002 when the Swedish national parliament, the Riksdag, decided on a second “daddy month,” while a negative abusive fatherhood role is most frequent around 2006 when the Riksdag decided on a presumption of joint custody for parents. An abusive fatherhood role is also frequent around 2017–2019 when various strategies to combat men’s violence against women are adopted by the Riksdag.

In the following, we start by anchoring our study in previous research on changes in fatherhood roles in Western democracies. Thereafter we elaborate on the theoretical proposition of continuous elite signaling as a mechanism producing norm change in society. We discuss the role of alternative triggers of change, such as pressure on men following from women’s increased participation in the paid workforce. The typology of relevant fatherhood roles is extensively discussed before we move to the presentation of the material and how we instructed GPT-4 to find the different depictions of fathers. All in all, we constructed a framework that facilitates distinctions between potentially encouraging and potentially stigmatizing portrayals of fathers, separating, first, between active and passive fatherhood roles, second, between active positive and active negative fatherhood roles, and, third, between different forms of active positive roles such as those linked to caring activities and those linked to outward-looking activities. The empirical section presents the results from the analysis by GPT-4 and relates these to parliamentary decision-making as well as to developments in Swedish fathers’ use of parental leave.

While the present study focuses on descriptions, we conclude by discussing possible causal relationships between elite signaling and fathers’ behavior: As noted above, one of our main findings is that while an active, positive fatherhood role is dominant in our material, the relative distance between this specific role and a negative, abusive fatherhood role, which society should be discouraging rather than encouraging, narrows over time. In parallel with this narrowing gap, we find a stagnation in the use of parental leave by Swedish fathers. Thus, there is evidence that signals from the political elite are mixed, which may contribute to ambivalent social norms and slow developments towards an equal engagement of mothers and fathers in the daily life of young children.

Expectations of Changes in Fatherhood Roles

Several studies note that fatherhood roles, over the past decades, have changed in Western Democracies and especially so in Scandinavian countries like Sweden (Dermott Reference Dermott2008; Dermott and Miller Reference Dermott and Miller2015; Karu and Tremblay Reference Karu and Tremblay2018; Martín-García et al. Reference García, Teresa and Castro-Martín2023; Tan Reference Tan2023). Changes are detected in behaviors such as fathers’ use of parental leave, but also in fatherhood ideals where Sweden is seen as a forerunner characterized by pervasive norms encouraging fathers to be actively involved in the everyday lives of their children. In particular, such ideals have been found in policy documents concerning families, parental leave, and gender equality (Andreasson et al. Reference Andreasson, Tarrant, Johansson and Ladlow2023; see also Cedstrand Reference Cedstrand2011; Fransson et al. Reference Fransson, Hjern and Bergström2018; Johansson Reference Johansson2011).

A number of qualitative studies (e.g., Lewington et al. Reference Lewington, Lee and Sebar2021; Lidbeck and Boström Reference Lidbeck and Boström2021; Solomon Reference Solomon2014), but also experimental research (e.g., Philipp et al. Reference Philipp, Büchau, Schober and Spiess2023; Scheifele et al. Reference Scheifele, Steffens and Van Laar2021) support the assumption that norms matter and that depictions of an agentic fatherhood role, emphasizing fathers as competent in relation to their children, has a positive effect on men’s intention to take parental leave. However, there is also research showing that social norms can be rather ambivalent in the way that stay-at-home fathering can be politically encouraged at the same time as those men who choose such roles – by other people, in media – are stigmatized (e.g., Kuperberg et al. Reference Kuperberg, Stone and Lucas2022). In short, there are good reasons to expect that a discursive shift has taken place and that the norms surrounding fatherhood in Sweden are positive in the sense that they encourage an active and involved father. However, the strength of a positive fatherhood role and its potential development over time needs to be compared with that of other fatherhood roles before drawing conclusions about whether a discursive shift has actually taken place.

A Theory on Continued Elite Signaling as Trigger of Behavior

The rationale for analyzing fatherhood roles and how portrayals of men as fathers potentially change over time is the belief that they are linked to social norms that, even if this is hard to measure, matter for behavior. Philipp et al. (Reference Philipp, Büchau, Schober and Spiess2023) theorize on the way by which certain norms embedded in parental leave policies may influence judgements of the appropriate number of days for fathers to use compared to mothers: First by a process of cultural diffusion and norm-setting at the societal macro level and then through a process of psychological preference adaption at the individual micro level. Thus, Philipp et al. (Reference Philipp, Büchau, Schober and Spiess2023) suggest that people react to signals sent by different representations of fathers in policy documents, i.e., in the language used when talking about fathers. And, building on survey experiments in Germany, they underpin the norm-setting effects of family policies. Concretely, the experimental study investigates how different types of information regarding parental leave alter respondents’ beliefs regarding the ideal division of parental leave. One main finding is that information tuning down negative effects on fathers’ wages leads to less traditional judgments regarding how parental leave should be divided between mothers and fathers.

Valentim (Reference Valentim, Grasso and Giugni2023) presents norm change as a coordination problem: That is, even if a norm is [politically] established people may act against that norm “if they are confident that a sufficiently large number of others are also opposed to the norm.” To make appropriate judgements people seek to update their perceptions as to what is deemed acceptable, and Valentim argues that institutional signaling is a mechanism through which such updates can occur. Our interpretation of Valentim’s reasoning is that norms embedded in policy documents are not enough to enforce far-reaching change in society, i.e., there is a need for additional signaling in the direction of the views expressed in decisions made. Building on Valentim (Reference Valentim2021, Reference Valentim, Grasso and Giugni2023), our theoretical proposition is that norm change in society is more likely to occur when members of a political institution, such as a national parliament, continuously send signals in a certain direction, in our case in the direction encouraging an active and engaged fatherhood role.

Alternative Triggers of Change

As Hall (e.g., Reference Hall1973) famously has pointed out, all messaging entails an encoding and decoding process, meaning that intentions embedded (encoded) in, for example, a legislative text, are not always understood (decoded) in the expected way by the receiver. Moreover, Hall’s media analyzes highlight that newspapers, magazines, television, social media, etcetera, are likely to be important transmitters of elite messaging since few people read legislative texts or in other direct ways follow parliamentary processes.

In addition to the above discussion on transmitters of institutional elite signaling, it should be recognized that while portrayals of men as fathers in public documents may play a role for behavioral change, scholars recognize a number of additional sources for the emergence of new ideals on fatherhood among broad layers of the population: e.g., second-wave feminism and the entrance, in large numbers, of women in the paid workforce; increased number of divorces and single-mother families; the development of fathers’ rights groups; emerging evidence that fathers’ involvement affects children’s physical and psychological health (del Carmen Huerta et al. Reference del Carmen Huerta, Adema, Baxter, Han, Lausten, Lee and Waldfogel2013; Dermott Reference Dermott2008; Dermott and Miller Reference Dermott and Miller2015; Sarkadi et al. Reference Sarkadi, Kristiansson, Oberklaid and Bremberg2008). What is implied by such research is that changes in policy documents may be a consequence of changes in people’s everyday lives rather than a driver of such change.

While recognizing the complexity of potential relationships, we find it reasonable to believe that elite signaling through legislative texts matters for behavior. In this study, we provide a first step toward future, more explanatory work by providing a comprehensive mapping of different types of fatherhood roles and relating the results to both decision-making and actual use of parental leave by fathers.

Developing a Framework for Analyses of Fatherhood Roles

The exact description of the “new father,” recognized in previous research (e.g., Dermott Reference Dermott2008; Dermott and Miller Reference Dermott and Miller2015; Kangas and Lämsä Reference Kangas, Lämsä and Jyrkinen2019; Rane and McBride Reference Rane and McBride2000) varies between studies, but keywords used to describe the old, once hegemonic role,Footnote 2 are that fathers used to be something of the “invisible man” in debates on families and parenthood and when they appeared, it was mainly in the role of “breadwinner” or in the role of a “disciplinarian, educationalist and moral authority” (Dermott Reference Dermott2008, 27). At heart of the new type is then the expectation on fathers to be both more directly involved in the upbringing of their children and display more caring or nurturing characteristics than fathers of previous generations (Dermott Reference Dermott2008; Dermott and Miller Reference Dermott and Miller2015; Lamb et al. Reference Lamb, Pleck, Charnov and Levine1985). Overall, these different expectations can be summarized as a wish for an adaption among fathers to a role of caring masculinity containing features often portrayed as typical of mothers (Kuperberg et al. Reference Kuperberg, Stone and Lucas2022; Randles Reference Randles2018).

In parallel to reasoning on caring masculinities, there is a strand of research that highlights a wish for fathers to acquire their own distinct parenthood roles. For example, Dermott and Miller (Reference Dermott and Miller2015, 184) use the expression “fathers as fathers” to capture this dimension and emphasize the need for research to provide alternatives to “mothering” as the parenting norm and standard against which fathering is measured (see also Dermott Reference Dermott2008, 91). In similar lines of reasoning, Volling and Palkovitz (Reference Volling and Palkovitz2021) stress the need for research to move beyond models of parenting derived predominantly from theories, research, and measurement of mothering and mother-child relationships (p. 427). Thus, they suggest a fatherhood role that builds on “traditional masculine agency” that encourages risk-taking among children (p. 430) which is contrasted to the traditional feminine caregiving role. Paquette et al. (Reference Paquette2004) label these different perspectives a “mother-child attachment relationship” role, aimed at calming and comforting children, versus a “father-child-activation relationship” role, aimed at development of a child’s openness to the world.

In an experimental study, conducted in Germany, Scheifele et al. (Reference Scheifele, Steffens and Van Laar2021) build on similar distinctions as Paquette et al. (Reference Paquette2004) and test which are the portrayals of fathers that affect men’s parental leave-taking intentions the most. More specifically, they (Scheifele et al. Reference Scheifele, Steffens and Van Laar2021) distinguish between “communal” versus “agentic” engagement in their portrayals, mimicking newspaper articles, where communal engagement corresponds to being emotional, empathetic, trustworthy, and agentic engagement to being ambitious, assertive, and competent. Their finding is that a combination of agency and communion increases men’s parental leave-taking intentions, and this is also the case for the portrayal exclusively focusing on agency. Yet, an exclusive focus on communion did not yield any similar effect.

In conclusion, in our review of the literature we note a dividing line between, on the one hand, a passive or even invisible fatherhood role of the past and, on the other hand, an active role that started to appear in public debates and academic literature in the 1980s. In addition, we note a dividing line between an active negative role where fathers are engaged with their children but in ways that might need to be restricted, and an active positive role increasingly encouraged by policymakers. We note that the active positive role can have either caring or outward-looking features, or a mix of them, at the center of the portrayal. In the section of methodology, we operationalize these categories included in the framework.

Case Selection and Hypotheses

The theoretical proposition we highlight is that elite signaling embedded in legislative texts – the language surrounding men as fathers in parliamentary documents – matter for behavior. We provide a comprehensive mapping of the first step of this theoretical reasoning, i.e., the actual scale of the different types of signaling from elites. We focus on one country, Sweden, over almost three decades (1993–2021). This delimitation allows us to search for fatherhood roles in a complete material, i.e., all parliamentary documents. Our main interest is in the distinction between an active and engaged fatherhood role, encouraged by policy initiatives like non-transferable days in parental leave, and a more traditional passive breadwinning fatherhood role of the past. We are also interested in the prevalence of a fatherhood role that is active in the sense that this is a father who engages with his children but in ways that, by policymakers and society at large, are negatively valued since activities might be abusive. This negative type of fatherhood role is not extensively discussed in the literature on shifting ideals, but we have seen examples in current political debates in Sweden, where, for instance, a recent motion to the Riksdag declared that: “A father who hits is not a good father and not a good role model. It should be possible to restrict custody and contact further and in more cases.”Footnote 3

Taking the reasoning in previous research into account, which suggests that social norms of an active and engaged fatherhood are pervasive in Sweden, we find it reasonable to assume that male agency, in the form of an active and positive fatherhood role, is highly prevalent among the political elite in this country. In addition, we find it reasonable to assume that there has been a discursive shift in the period we study whereby the active positive fatherhood role over time becomes more prominent and states as our first two hypotheses:

H1a: That an active positive fatherhood role is prevalent in Swedish parliamentary documents and dominates over other types of fatherhood roles (e.g., a passive role and/or an active negative fatherhood role).

H1b: That there is not only a dominance of an active positive fatherhood role in Swedish parliamentary documents but also an increase, over time, in the prevalence of such a role in relationship to other potential fatherhood roles (e.g., a passive role and/or an active negative fatherhood role).

Our theoretical proposition is, as previously stated, that norm change is more likely to occur when members of a political institution, such as a national parliament, continously send signals in a certain direction, in our case in the direction encouraging an active and engaged fatherhood role. At the same time, however, it is reasonable to believe that fatherhood roles, as a phenomenon, are especially concentrated in periods when political decisions are made that explicitly relate to fathers’ behavior, and therefore we hypothesize:

H2: That mentions of fatherhood roles are most frequent in connection to decision-making with bearing on fathers’ behavior.

Finally, we take a first step towards causal interference of relationships between elite signaling and real-world behavior by describing whether mentions of an active and engaged (positive) fatherhood role precede changed behavior and hypothesize:

H3: That mentions of an active positive fatherhood role is especially frequent in periods preceding noticeable changes in fathers’ behavior as measured in the use of parental leave.

To capture developments over time, we have divided the material into seven different time periods that largely follow election cycles in Sweden: 1993–1997, 1998–2001, 2002–2005, 2006–2009, 2010–2013, 2014–2017, and 2018–2021.Footnote 4 Since previous research differentiates between various forms of positive fatherhood roles, distinguishing between more general descriptions and those that specifically portray fathers as caring or in roles that encourage children’s outward-looking activities, we have included such distinctions in our analysis. The fine-grained categories under the umbrella “active positive fatherhood role” are, however, not of main interest in our analysis.

Data and Methodology

In this section we focus on the operationalization of different fatherhood roles and the use of LLMs to measure their prevalence in the period 1993–2021.Footnote 5 The data and methodology used for the analysis of policymaking and changes in father’s use of parental leave will be presented and discussed in connection with forthcoming sections.

Choice of Material

One major point with LLMs is that they allow for the processing of large amount of text without the need for training data. The risk with more narrowly selected data is that choices can bias results. A case in point is analyses that focus exclusively on family and/or gender equality policy documents in Sweden, which several scholars note are impregnated with norms of an actively engaged father (Andreasson et al. Reference Andreasson, Tarrant, Johansson and Ladlow2023; Cedstrand Reference Cedstrand2011; Fransson et al. Reference Fransson, Hjern and Bergström2018; Johansson Reference Johansson2011). LLMs allow us to search for fatherhood roles in documents outside the range of parental leave/family policies since our database includes all parliamentary motions, propositions, written questions, government inquiries, etcetera, during the period 1993–2021.Footnote 6

Unit of Analysis

In the downloaded textsFootnote 7 we started our analysis by using target words to find instances in the material mentioning “fathers,” “mothers,” “parents,” or equivalent words. In total, we ended up with 277,168 sentences or shorter text sections including any of these keywords. Thereafter we singled out the instances where these words were used as nouns, and not as verbs or other types of words. This means that our analysis takes into account that “far” in Swedish also is a verb that denotes “go” or “travel”.Footnote 8 Table 1 shows the used target words.

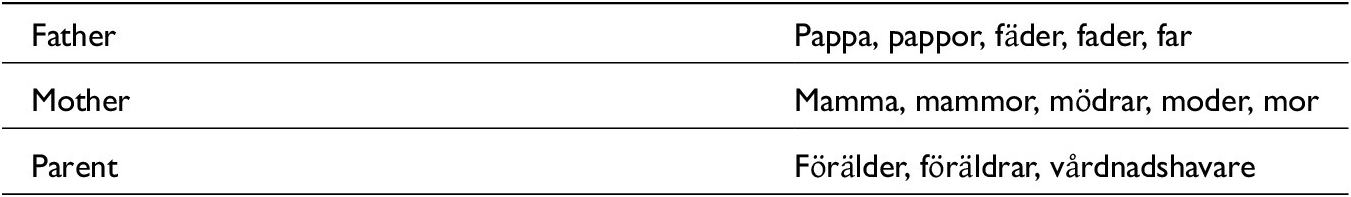

Table 1. Target words used for father, mother, and parent

All in all, we ended up with 151,489 sentences that included the keywords in Table 1 as nouns. The overwhelming proportion of these sentences talked about parents and did not single out fathers or mothers as separate actors. Only 1,901 sentences mentioned fathers and 2,821 mentioned mothers. Out of the 1,901 sentences mentioning father, a manual annotation (see Lupo et al. Reference Lupo, Magnusson, Hovy, Naurin and Wängnerud2023) alerted us to the fact that a significant amount of the text did not talk about the father in relation to a child but looked at fathers from a biological point of view, e.g., as sperm donors, or in legal aspects such as gay rights, citizenship, or heritage issues. After filtering out these non-relevant instances, the final material amounted to 1,448 sentences or shorter text sections mentioning fathers as a parent, i.e., in relation to children.

Operationalizing Fatherhood Roles

In our previous review of the literature, we distinguished between a passive and an active fatherhood role. In addition, we noted a dividing line between an active negative fatherhood role and an active positive fatherhood role, where the positive role could either center on caring aspects or outward-looking features. References to an active positive fatherhood role can also be more general. We operationalized the different categories as follows:

PASSIVE

This is a category that captures what is sometimes called the traditional role given to and taken by fathers, which in essence is a role that does not include engaging with the child. Here the father is a person who is important in the life of the child but is not directly involved in the hands-on caring and upbringing. Indicators in this category are notions such as breadwinner, provider, custodial parenthood.

ACTIVE_NEGATIVE

This is a category that captures an active but negative role of fathers, such as the oppressive father, the harsh and violent father, as well as neglecting father. Society needs to create policies around this father to restrict/stop him. Indicators are notions such as dangerous, punish, aggressive, violent, oppressive, not paying child support.

ACTIVE_POSITIVE_CARING

This category focuses on what is sometimes seen as a (stereo)typically feminine parental role. Indicators are notions such as caring, warm, nurture, understanding, empathy, listening, comfort, confirming.

ACTIVE_POSITIVE_CHALLENGING/DARING

This category focuses on what is sometimes seen as a (stereo)typically masculine parental role. It focuses on outward-looking activities and indicators are notions such as risk-taking, daring, try your limits, sport, outgoing, education (including, in the Swedish case, reading to child since reading at the time was mainly discussed as an outward-looking activity in reference to broaden the mind of, enlighten, show the world to, etcetera).

ACTIVE_POSITIVE_OTHER

Most typically, the other category indicates agency in a general, less gender-typical sense, i.e., that the father is competent and reliable, and should be trusted with the child, but it does not single out why. Indicators are general references to capability, responsibility, rights of, and trust in fathers to handle information, take parental leave, get parental allowance, be present in the life of the child, be an unspecified positive role model (“boys/girls need male role models”).Footnote 9

NOT_APPLICABLE

Sometimes sections/sentences in the material include the word father in relation to a child but it is not possible to detect a certain normative signal. These instances are denoted “not applicable” and excluded from the final analysis. When these instances are excluded, we are left with 1,230 sentences or sections such as shorter paragraphs to analyze.

The abovementioned categories (aside from not applicable) are also labeled either as describing a state (DESCRIPTIVE) or an ideal (IDEAL). The reason is that norms can be either descriptive or prescriptive (“we see that fathers are active” or “we wish for more active fathers”). Furthermore, fatherhood roles can appear in the material in ways that are either highly EXPLICIT or more IMPLICIT.Footnote 10

The Methodological Strategy Footnote 11

The primary methodology used is a Natural Language Processing (NLP) method based on a large language model (LLM). LLMs have been trained to predict the next word in a sentence on a large amount of text data (essentially the entire available internet, including code). Consequently, they have learnt an inherent model of how language works and can generate text based on a prompt, as its plausible continuation. Hence, they can be used for various tasks, such as classifying text into different labels, making them an apt tool to classify sentences into pre-determined categories at scale. The advantage of LLMs relative to traditional text classification techniques based on machine learning is that they can learn the labeling task from just a few examples instead of requiring thousands of training examples (Brown et al. Reference Brown, Mann, Ryder, Subbiah, Kaplan, Dhariwal, Neelakantan, Shyam, Sastry, Askell, Agarwal, Herbert-Voss, Krueger, Henighan, Child, Ramesh, Ziegler, Wu, Winter, Hesse, Chen, Sigler, Litwin, Gray, Chess, Clark, Berner, McCandlish, Radford, Sutskever and Amodei2020). We use an LLM to add our theoretically derived categories to the full sample as well as for filtering out non-relevant sentences, i.e., not applicable or men/fathers in “purely” biological/legal terms.

Labeling Sentences

We use the LLM GPT-4 (Generative Pretrained Transformers) from OpenAI. We provide GPT-4 with 15 examples of sentences from our corpus that we manually labeled with the three desired labels (type of fatherhood role, descriptive/ideal, and implicit/explicit). GPT-4 uses those examples to learn how to label the other sentences with the same labels. We then let GPT-4 label the whole sample.

A simple way of describing the method would be: The first step in this process was to decide on labels we wanted the LLM to use. We first derived and refined a set of labels based on existing theory. After that, we found one or two examples of sentences that fit each of these labels. We fed the set to GPT4 along with a description of the task and the same set of label explanations as we provided to human annotators during the reliability test and let the LLM use those to decide how to label other similar sentences. We check whether the predicted labels on those sentences conform to our expectations. If they do not, we provide GPT4 with more examples of sentences that should have the desired labels. Once we are happy with how the computer uses the labels (in our case, after providing around 15 example sentences), we prepare for a reliability test (see Lupo et al. Reference Lupo, Magnusson, Hovy, Naurin and Wängnerud2023 for details).

The reliability of the LLM annotation was tested by comparing its performance on 350 randomly sampled sentences to that of three human annotators, all of whom are authors of this article. Once all annotators (humans as well as the LLM) had independently labeled the same 350 sentences, the average agreement between the humans was compared to the average agreement of the LLM and the humans. The test result suggested that the LLM on average had a higher agreement with humans’ annotators than the humans had with each other on two tasks (fatherhood role and descriptive/ideal) and performed on par with the humans on the third task (implicit/explicit). Upon the satisfactory results, we finally moved on to have the LLM label the full selection of sentences.

Wordify Analysis

To strengthen the claim that the different theoretically deduced fatherhood roles also exist empirically, we conducted a Wordify analysis as an additional empirical strategy. Wordify (Hovy, Melumad, and Inman Reference Hovy, Melumad and Inman2021) is a tool that identifies which words best discriminate between texts from different pre-determined categories. Broadly, the algorithm repeatedly fits logistic models to a random sample of words from the categories (here: fatherhood roles) and applies machine learning techniques to increase the probability that these words are representative of the entire corpus. The output of the procedure is a list of words with an associated marginal probability score that are able to discriminate among the categories over a large number of regressions. To decide the specificity of the tool, a threshold is chosen to decide the number of times a word needs to get a significant score in the regression to be chosen. In our case, we set the threshold to 30 percent over 1000 iterations. In the presentation of these results, we also include illustrative examples from the material.

The Frequency of Fatherhood Roles, 1993–2021

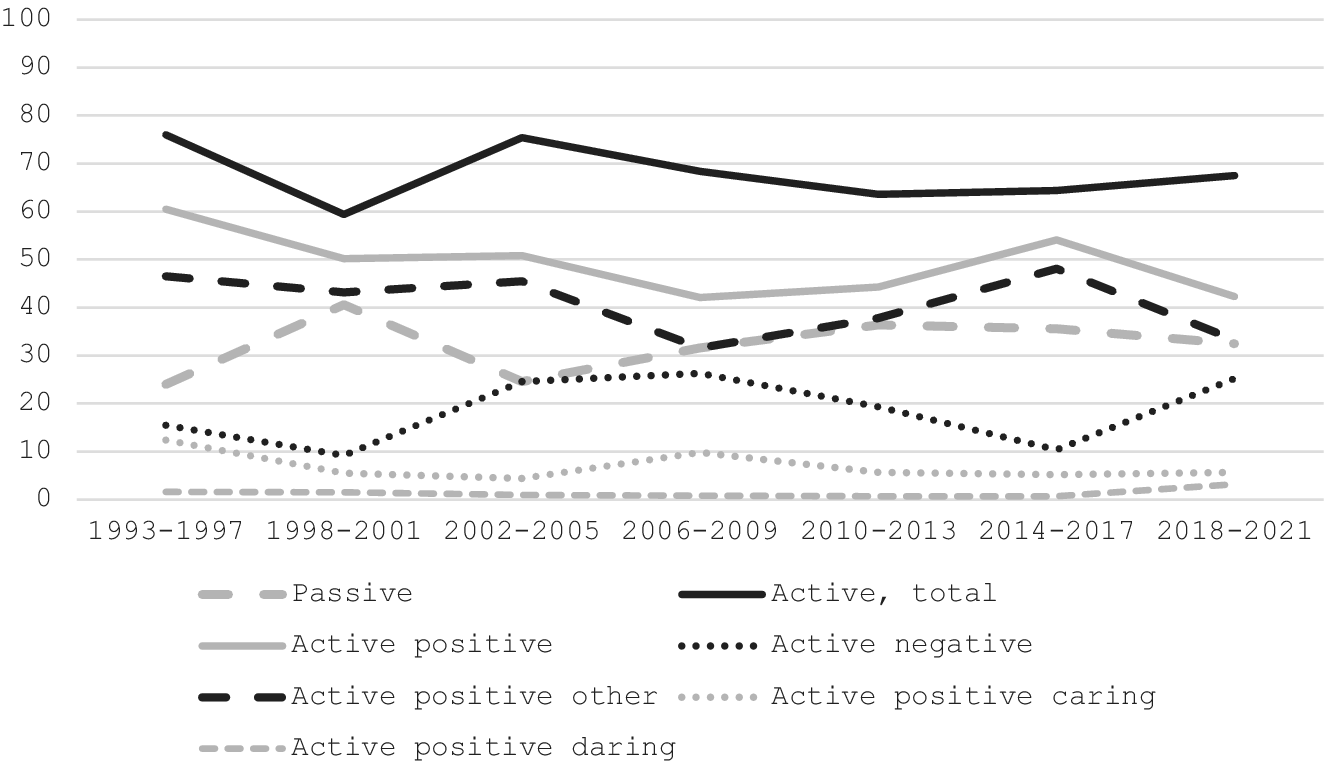

We shall start by reporting the distribution of the different categories of fatherhood roles in the total material 1993–2021 and the variation in mentions of fatherhood roles (all categories merged) over seven time periods 1993–1997, 1998–2001, 2002–2005, 2006–2009, 2010–2013, 2014–2017, and 2018–2021. Figure 1 shows results in three different groups: (i) the category “active” (active positive and active negative merged) compared to the category “passive,” (ii) the category “active positive” (active positive other, active positive caring, and active positive challenging/daring, merged) compared to the category “active negative,” and (iii) “active positive other” compared to “active positive caring” and to “active positive challenging/daring.”

Figure 1. Distribution of different categories of fatherhood roles 1993–2021 (%).

Notes: In each of the three groupings in Figure 1, there are 1.230 sentences/shorter text sections as the basis for calculation. “Active” corresponds to a role where fathers are involved in the daily lives of their children which can take “positive” forms and be encouraged by policymakers but also “negative” abusive forms where engagements need to be restricted by society. “Passive” corresponds to a traditional breadwinning fatherhood role. “Active positive caring” corresponds to a role where warmth, empathy, and comfort are central elements, whereas “active positive daring” corresponds to a role where risk-taking, trying limits, and education are central. “Active positive other” is a role indicating that fathers are competent and reliable in relation to their children but is rather general as to why this is the case. Active total is a summary of active positive others, active positive caring, and active positive daring. Categories are more fully described in the section on data and methodology.

The results in Figure 1 show that, in Swedish parliamentary documents 1993–2021, the active fatherhood role (67.8 percent) dominates over the passive fatherhood role (32.2 percent) and that the active positive fatherhood role (49.5 percent) dominates over the active negative fatherhood role (18.3 percent).Footnote 12 Among the different active positive fatherhood roles, it is the category “other” that dominates (41.8 percent) while the “active positive caring” role is more common (6.4 percent) than the “active positive challenging/daring” role, which is uncommon (1.3 percent). Thus, we can confirm H1a “That an active positive fatherhood role is prevalent in Swedish parliamentary documents and dominates over other types of fatherhood roles (e.g., a passive role and/or an active negative fatherhood role)” since the results show that when there is an explicit mentioning of fathers in their role as parents in these documents it is most often in an active role, and that references most often are positive but rather general, e.g., referring to fathers as capable and responsible but not stating why this is the case (active positive other).

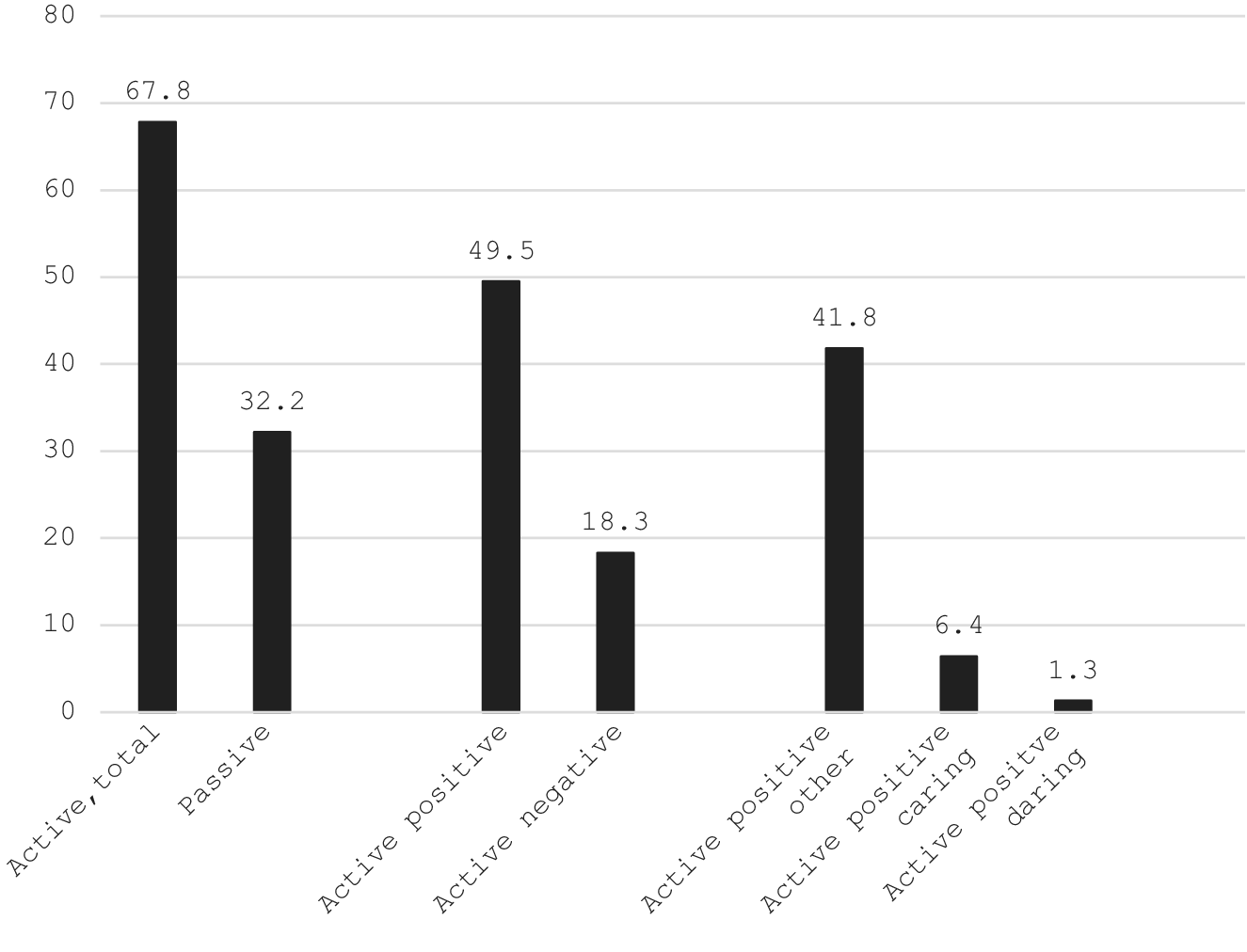

In Figure 2, we can see that there is a peak in mentions of fatherhood roles during the periods 1998–2001 and 2002–2005, where almost half (in total 46.3 percent) of the mentions occur. Mentions are otherwise evenly distributed with approximately 10 percent in each period. We will get back to this result in the analyses of policymaking and fathers’ use of parental leave.

Figure 2. Distribution of fatherhood roles mentions divided into periods (%).

Note: The basis for calculation is 1.230 sentences/shorter text sections.

Developments Over Time

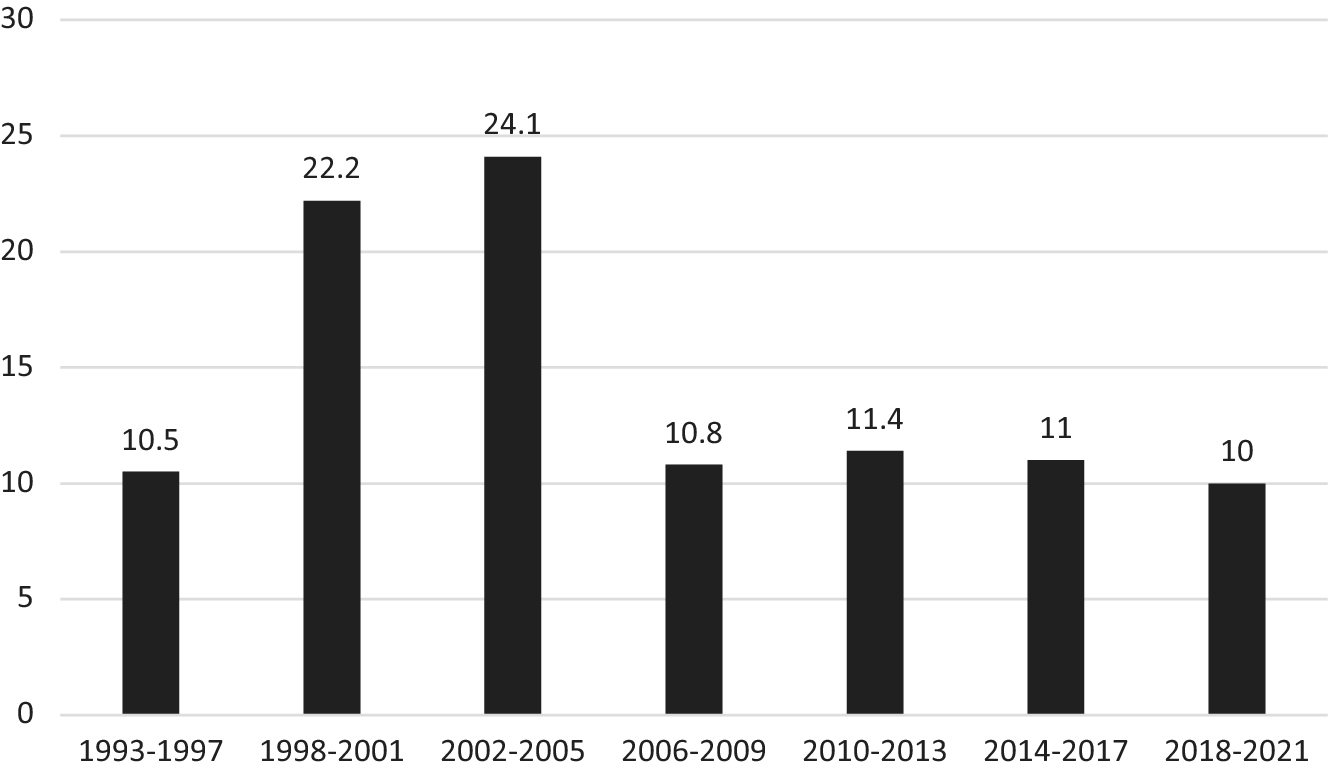

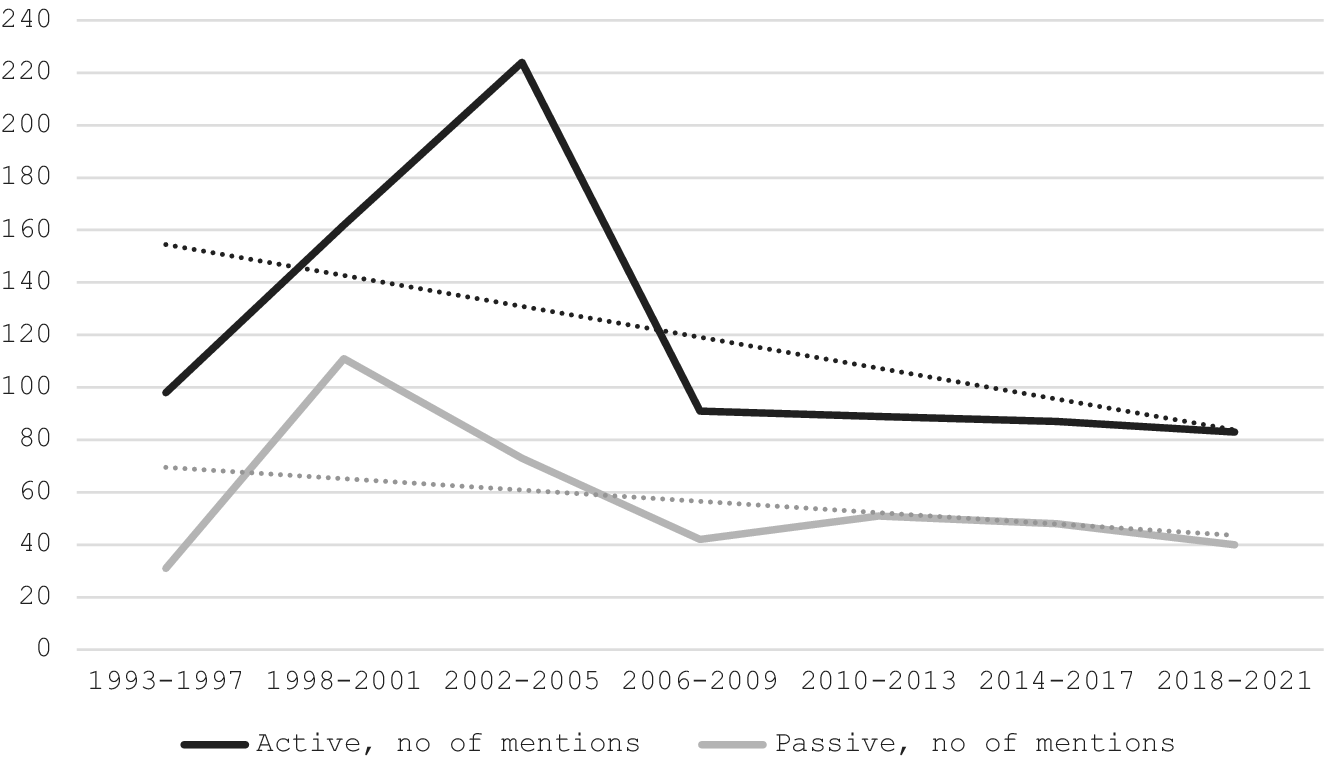

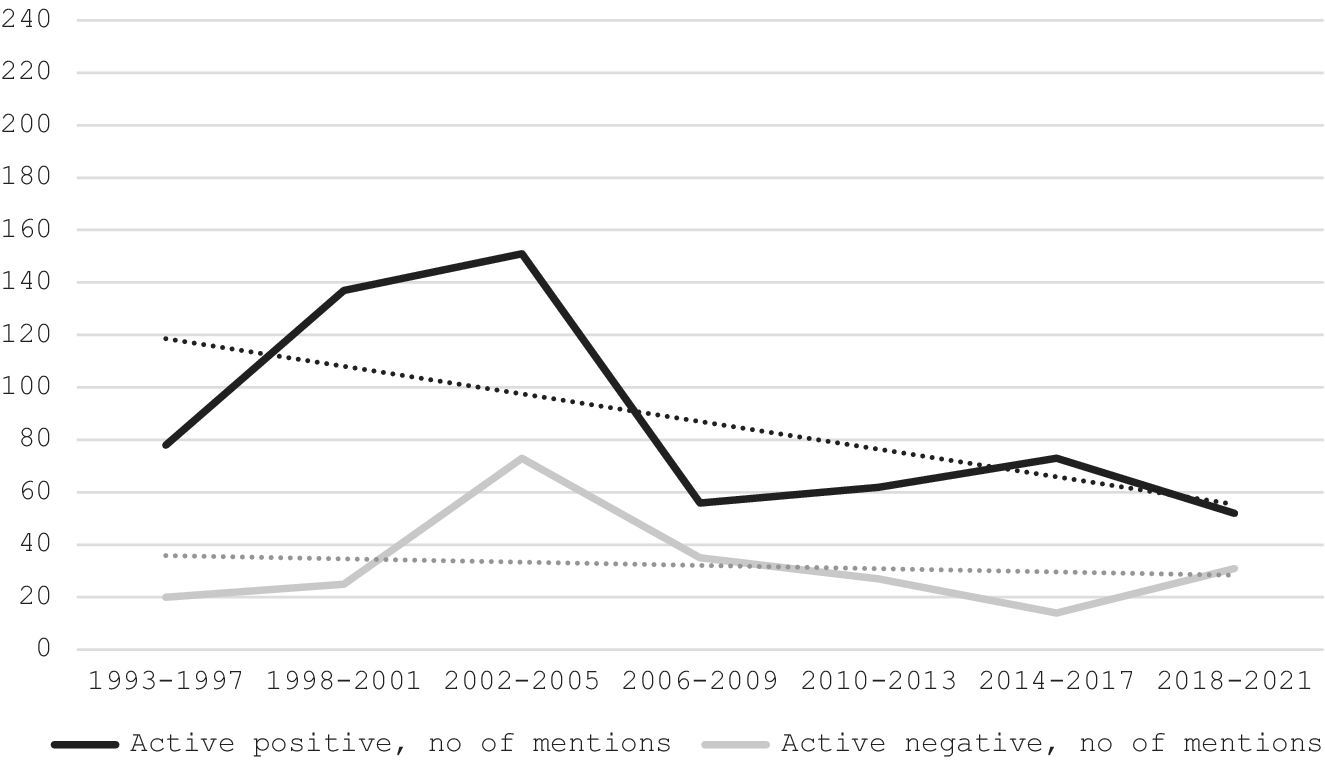

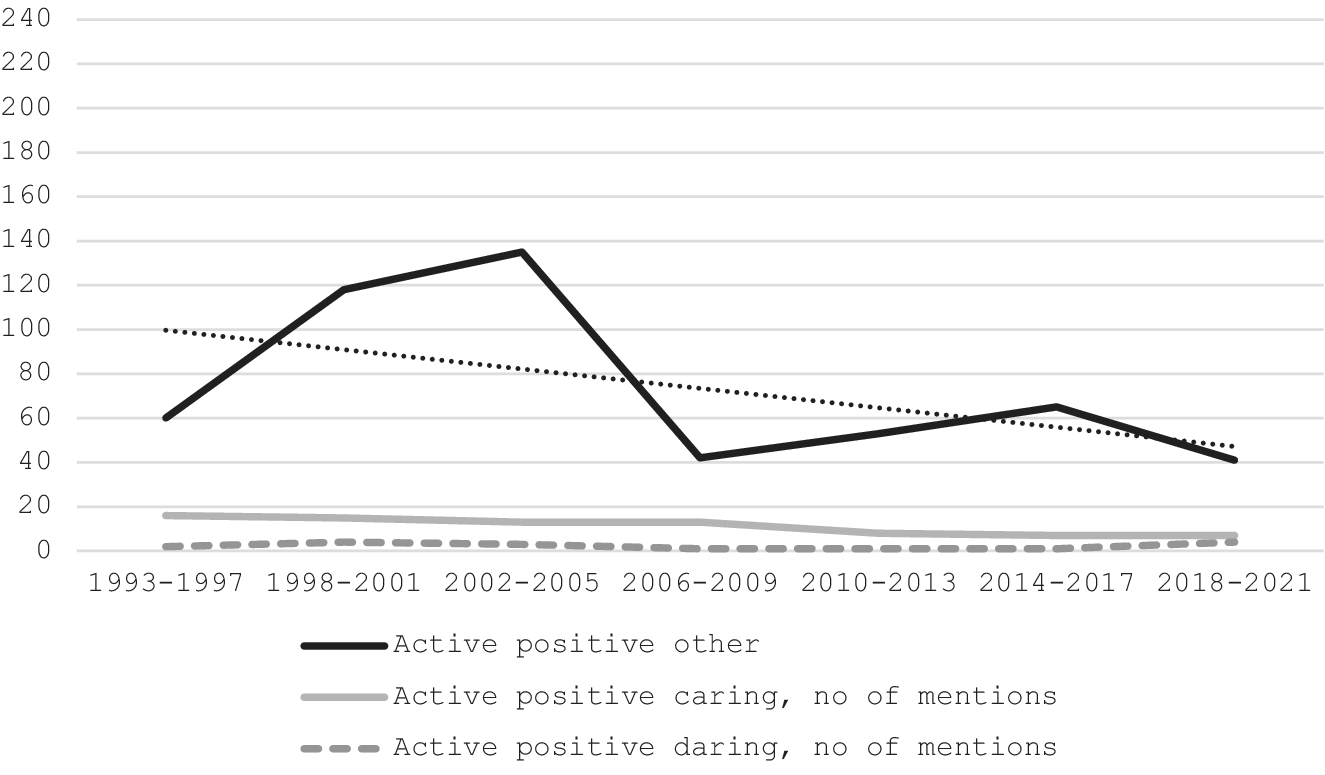

Our second hypothesis concerns patterns over time and states H1b “That there is not only a dominance of an active positive fatherhood role in Swedish parliamentary documents but also an increase, over time, in the prevalence of such a role in relationship to other potential fatherhood roles (e.g., a passive role and/or an active negative fatherhood role).” Below follow three figures related to hypothesis H1b. First, Figure 3 includes mentions, in total numbers, of a passive fatherhood role as compared to an active fatherhood role divided into the seven time periods. Second, Figure 4 includes mentions, in total numbers, of an active positive fatherhood role compared to an active negative fatherhood role. Finally, Figure 5 includes the mentions, in total numbers, of an active positive caring, an active positive challenging/daring, and an active positive other (more general) role. The separation into different figures is done to increase accessibility of results (in each analysis included in Figures 3–5, there are 1.230 sentences/shorter text sections as the basis for calculations, see Figure 1 for a description of the different categories).

Figure 3. Mentions of a passive fatherhood role compared to an active fatherhood role divided into different time periods, including trend lines (total number of mentions).

Figure 4. Mentions of an active positive fatherhood role compared to an active negative fatherhood role divided into different time periods, including trendlines (total number of mentions).

Figure 5. Mentions of an active positive “other” fatherhood role compared to an active positive “caring” and an active positive “daring” role divided into different time periods, including trendline for “other” category (total number of mentions).

The results in Figure 3 show that the active fatherhood role (black line), in all time periods, dominates over the passive role (gray line) in the sense that there are more mentions referring to an active role compared to mentions referring to a passive role. Interesting to note is that the peak for the passive role appears in the period 1998–2001, whereas the peak for the active role appears in the period 2002–2005. Overall, the trendline for the passive role is comparatively flat whereas the overall picture for the active role is a downward trend.

Moving to Figure 4, the results show that mentions of an active positive fatherhood role (black line) are more common in all time periods than the mentions of an active negative role (gray line). However, in the periods 2006–2009 and 2018–2021 the difference is comparatively small. Most important to note is the peak in mentions of an active negative fatherhood role that appears in the periods 2002–2005 and 2018–2021. Finally, the results in Figure 5 show that the trend for the active positive “other” role (black line) is very similar to the trend for the merged category active positive role (Figure 4). This follows from the fact that the other two categories – positive active caring (gray line) and positive active challenging/daring (gray dashed line) – are small. Thus, when fathers in Sweden are portrayed in an active positive role it is mainly in rather general terms.

In summary, H1b, stating that there is not only a dominance of an active positive fatherhood role in Swedish parliamentary documents but also an increase over time, cannot be confirmed. What the results show most clearly are fluctuations over time where, for example, there is a temporary increase in the mentions of a passive fatherhood role in the period 1998–2001 and a similar temporary increase in the mentions of an active positive fatherhood role in the period 2002–2005. Looking at the trendline in Figure 4, a downward trend for the mentions of an active positive fatherhood role appears, but most important to note in Figure 4 is perhaps the trend towards a narrowing gap between the mentions of an active positive and an active negative fatherhood role.

Before moving on, we include a different way of presenting developments over time and that is in percentages instead of in total numbers. Figure 6 shows the share of mentions in each category based on the total number of mentions in the different time periods (see Figure 2). Two results are accentuated when mentions are calculated as percentages instead of in total numbers and that is (i) that mentions of a passive fatherhood role (grey dashed line) is relatively stable 1993–2021 and (ii) an increase in the appearance of an active negative fatherhood role (black dotted line) relative to the other categories in the last period, 2018–2021.

In conclusion, while an automatic labeling technique such as the one applied in this paper can make errors, we are confident in the main results presented in Figures 1–6 since our reliability tests have demonstrated very high agreement between the automatic coding and coding by humans (see Appendix and Lupo et al. Reference Lupo, Magnusson, Hovy, Naurin and Wängnerud2023). By main results, we refer to the co-existence of an active positive, a passive, and an active negative fatherhood role in Swedish parliamentary texts throughout the whole studied period. All in all, the empirical analyses confirm a dominance of an active positive fatherhood role, but results go against the expectation regarding an upward trend in the appearance of this role and instead visualize fluctuations and an overall decreased distance between the active positive and the active negative fatherhood role in the period 1993–2021.

Wordify Analysis

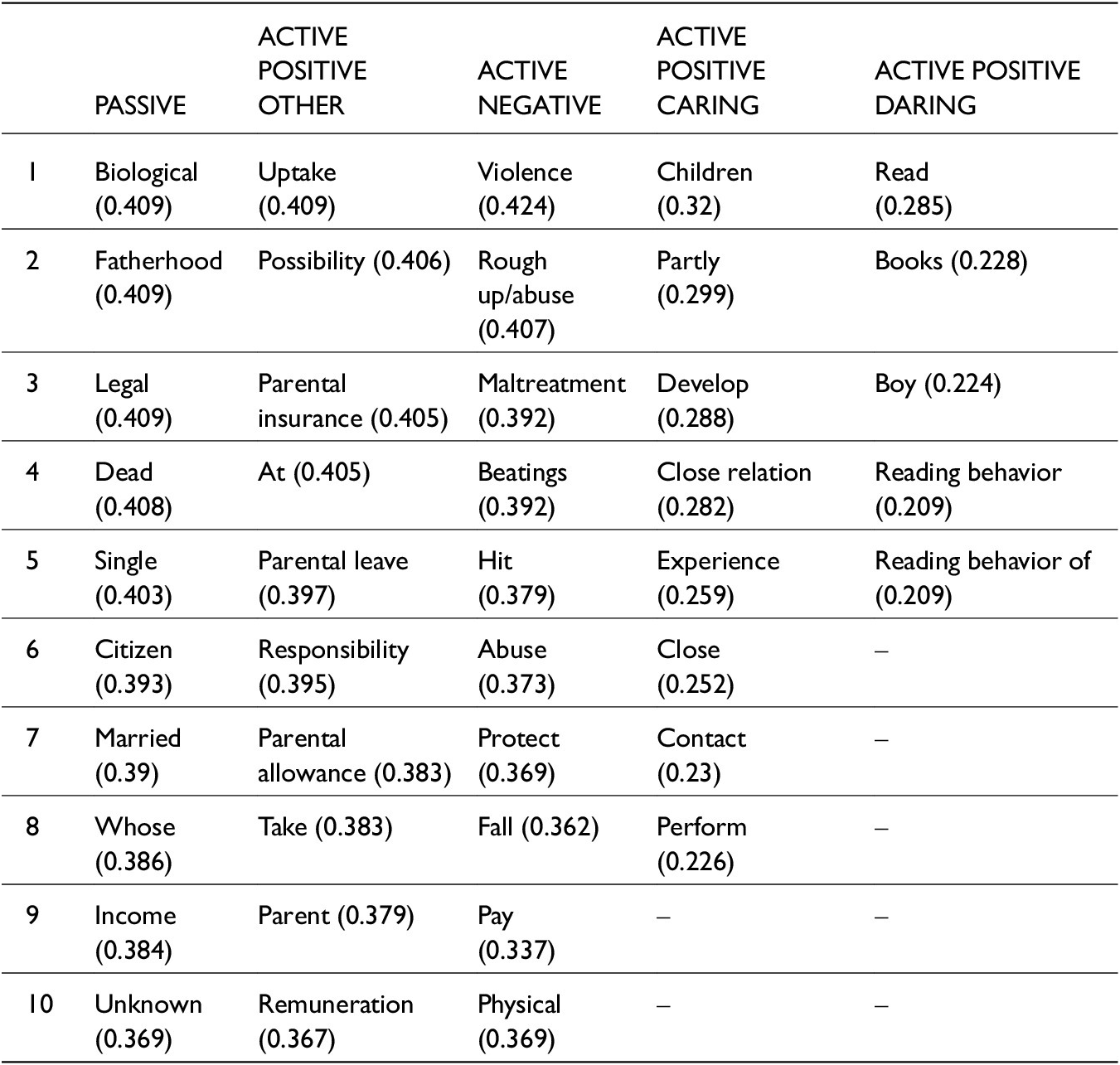

The following Wordify analysis generated the most characteristic words for each of the predefined categories. The words are presented in falling order according to their marginal probability score (how likely a random sentence drawn from the specific category is to contain the words).

First, what can be noted in Table 2 is that for the larger groups in our analyses — the categories “passive,” “active positive other,” and “active negative” — the algorithm managed to find many characteristic words. Second, even though we made an initial cleaning of sentences referring to fathers in biological terms or legal aspects words like “biological” and “legal” appear as some of the most characteristic of the passive fatherhood role category. In the material there are examples of reasoning on who is the true (social) father with references to biology and/or marriage like in the following quote: “the man in the marriage is therefore automatically considered to be the father of the child regardless of whether he is actually the biological father or not” (code 61636).Footnote 13

Table 2. Wordify analysis of most characteristic words for each category (top 10)

Note: See section on data and methodology for description of the methodology.

As seen in Table 2, the most characteristic words for the active positive other category are “uptake,” “possibility,” and “parental insurance.” This can be illustrated by the following quote where the father is depicted as someone that the child has the right to be in contact with: “the importance and role of fathers for their children is highlighted more and more and the children’s right to both their parents has characterized the legislation of recent years” (code 68291). Another example from this category is: “we believe that…days should continue to be set aside for fathers and mothers separately -- this mainly as a marking of the children’s right to both their parents and the shared responsibility” (code 97013). In contrast, the most characteristic words of the active negative fatherhood role are “violence,” “abuse,” “maltreatment,” and “beatings.” Quotes reflecting this category are: “the daughter was traumatized after witnessing the violence her mother was subjected to by the father” (code 277902) and “they tend instead to talk about fathers’ violence against mothers and fathers’ violence against children as phenomena without a particularly strong connection to each other” (code 320442). Thus, the Wordify analysis emphasizes that the active negative fatherhood role is one that society should restrict, and that mothers and children need protection from this type of father.

For the category active positive caring some of the most characteristic words are “children,” “develop,” and “close relation.” Quotes from this category are: “the bonds between child and father are strengthened…the father’s early participation means a significant relief for the mother” (code 83799) and “this despite the fact that the fathers who have the courage to pursue a legal process in order to be allowed to live with their children are probably at least as involved in the children’s daily care as the children’s mothers” (code 109260). For the active positive challenging/daring category, the most characteristic words refer to reading which is seen in the following quote “to address and stimulate fathers to read to their children” (code 212294). Reading is an outward looking activity but perhaps less “daring” than what could be expected from previous research on (stereo)typical masculine parenthood roles. In future studies, the classification of “typical” masculine roles needs careful rethinking.

Fatherhood Roles and Policymaking

Even though we present a theory emphasizing continuous elite signaling, we find it reasonable to believe, as stated in H2, that mentions of fatherhood roles are most frequent in connection to decision-making with bearing on fathers’ behavior. Table 3 below shows a compilation made by Statistics Sweden regarding family policies in Sweden, 1993–2021. Several policies in Table 3 reflect trends in the national economy, improving economic conditions for families or imposing restrictions/cuts such as the policies from 1996, 1997, and 1998. However, there are also policies reflecting political norm-setting such as the introduction in 1995 of 30 non-transferable days in parental leave which was extended to 60 days in 2002 and to 90 days in 2016. In 2008 a “gender equality bonus” was introduced (abolished 2017).

Table 3. Policymaking in Swedish parental leave/family policy 1993–2021

Note: Source Statistics Sweden (https://www.scb.se/publikation/48074).

Going back to the results in the previous section regarding the frequency of different fatherhood roles, it is interesting to note the peak in mentions of a passive fatherhood role directly after the introduction of the first 30 non-transferable days in parental leave in 1995 (see Figure 3) and the peak in mentions of an active positive fatherhood role in the periods 1998–2001 and 2002–2005 (see Figure 4), i.e., around the extension of the non-transferable days in parental leave to 60 days in 2002. This may indicate that the 1995 reform was seen as less effective than hoped for, and that new expectations were attached to the introduction of a second “daddy month.” There is no peak in mentions of an active positive fatherhood role at the time of the introduction of the gender equality bonus in 2008 but a small increase (see Figure 4) in the period 2014–2017 when the number of non-transferable days was extended to 90 days. A preliminary conclusion is therefore that signals, likely to strengthen positive male agency, are most prevalent in connection with the introduction of additional so-called “daddy months.”

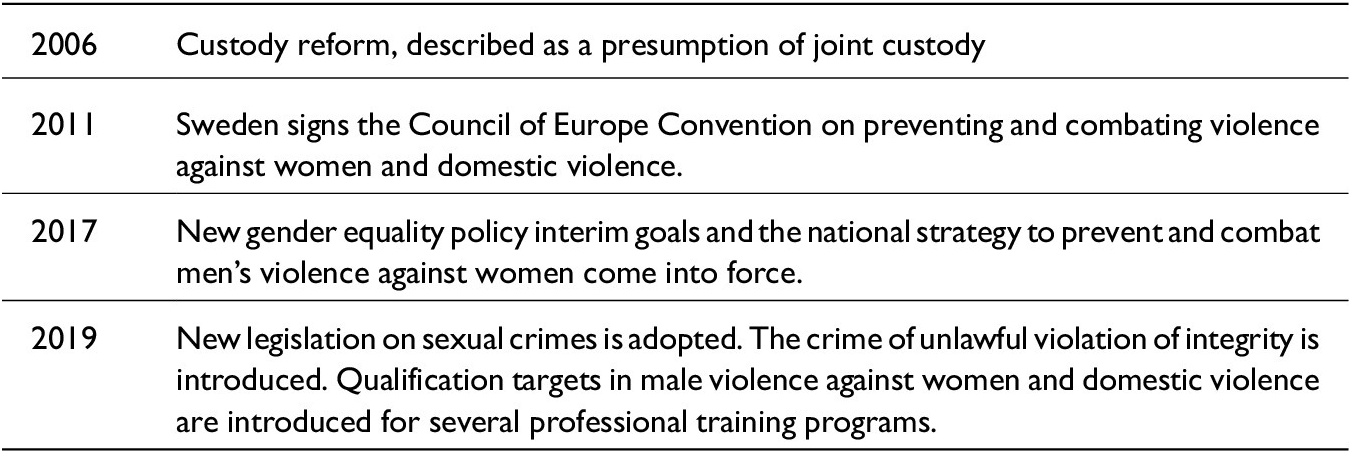

Our analysis on the frequency of different categories of fatherhood roles also showed the prevalence of an active negative fatherhood role that was most visible in the periods 2002–2005 and 2018–2021 (see Figures 4 and 6). Table 4 below shows policies compiled by Statistics Sweden that may be linked to these results. In 2006 a custody reform was introduced prescribing joint custody and before this policy was enacted critique was raised that this meant joint custody even if it exists cirumstances such a violent father which suggest that sole custody for the mother would have been better (Burman Reference Burman2016). In 2017 and 2019 new policies to combat violence against women were introduced with the aim of further restricting violence from male partners.

Table 4. Policymaking in Sweden regarding custody and violence against women

Note: Source Statistics Sweden (https://www.scb.se/publikation/48074).

In conclusion, what these results indicate is that mentions of men as fathers are particularly visible when legislative acts concern sharp initiatives such as non-transferable days in parental leave or joint custody but not when the bearing on fathers’ behavior is more diffuse such as in the suggestion of a gender equality bonus.

Fatherhood Roles and the Use of Parental Leave

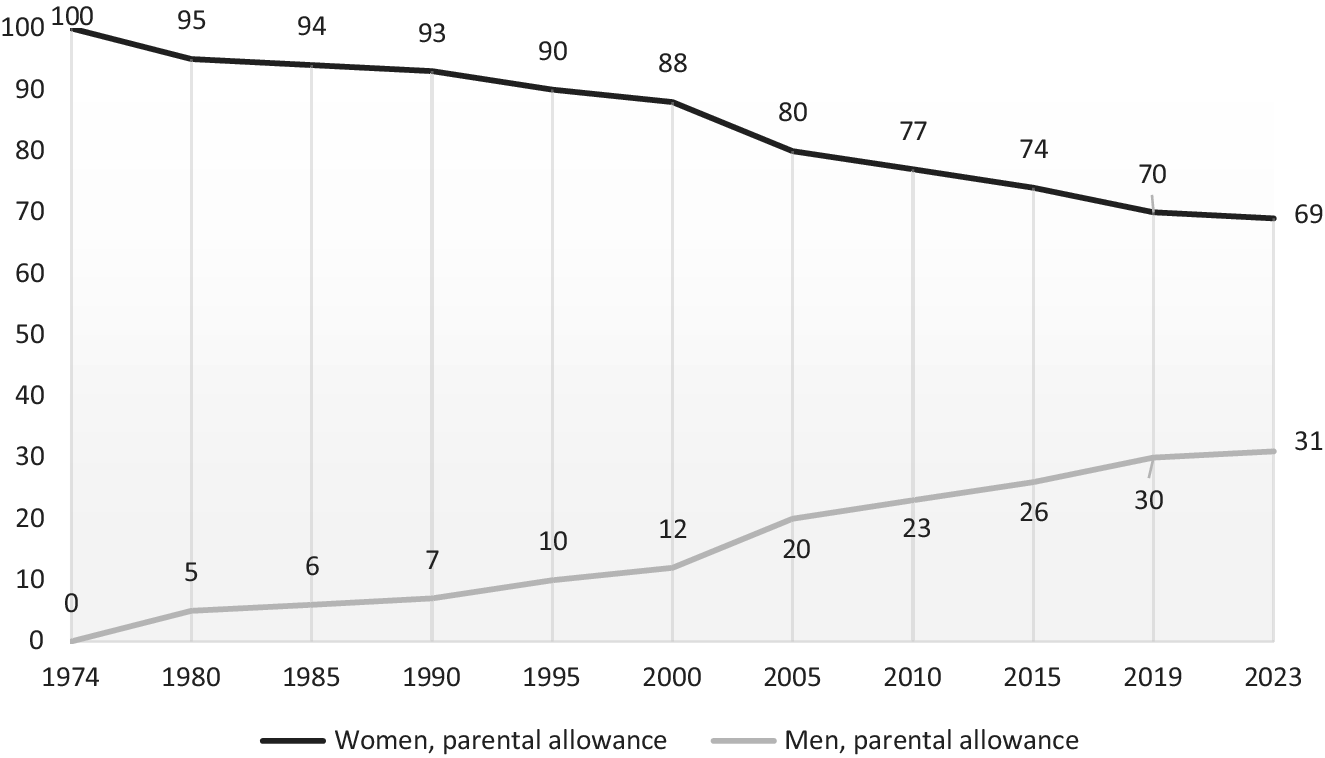

The final step of our analysis is then to investigate developments in fathers’ use of parental leave. As already stated, fathers in Sweden were granted the same right as mothers to take parental leave in 1974 (Cedstrand Reference Cedstrand2011). Data from Statistics Sweden (Figure 7) show that in 1974 no days of parental allowance were paid to men. Since then, there has been a stepwise increase with the sharpest rise, from 12 percent to 20 percent, between 2000 and 2005. In 2023, 31 percent of days for parental allowance were taken by men but this is a relatively small increase, one percentage point, since 2019 when the corresponding figure was 30 percent, and may indicate that the trend of a stepwise increase is leveling off.

Figure 7. Days for which parental allowance is paid for care of children, 1974–2023 (%).

Source: Statistics Sweden (https://www.scb.se/publikation/48074).

Bringing results from different analyses together, we can demonstrate that many things coincide around 2002: a peak in the mentions of an active positive fatherhood role, an extension of non-transferable days in parental leave to 60 days, and a comparatively sharp increase of eight percentage points in the number of days in parental allowance used by fathers. These findings are intriguing and indicate that neither changes in fatherhood roles nor stricter policies are on their own sufficient to influence behavior. It may be the case that it is a joint pressure from “harsh” policy and language encouraging (positive) male agency that matters the most for progressive change regarding fathers’ use of parental leave. However, we cannot fully confirm H3 “That mentions of an active positive fatherhood role is especially frequent in periods preceding noticeable changes in fathers’ behavior as measured in the use of parental leave” since this part of our study is foremost explorative.

Conclusions

In this study we have, with the help of LLMs, been able to demonstrate that even if an active positive fatherhood role dominates in Sweden in the period 1993–2021, as expected from previous research, there are several co-existing fatherhood roles, ranging from an active positive role, encouraged by various policy initiatives, to a traditional more passive fatherhood role, to an abusive role which society needs to restrict. Hence, elite signaling is mixed which may contribute to social norms being ambivalent and not fully corresponding to messages embedded in policy initiatives such as non-transferable days in parental leave (so-called daddy’s months) or gender equality bonuses. Since the data cover almost three decades and several shifts in government (see endnote 4) we conclude that the type of parties in power — whether they are ideologically left or right leaning — does not matter that much for the overall picture but in future research it would be interesting to look further into the details and distinguish which parties that signals what type of fatherhood role. Even lack of elite signaling from specific parties would be interesting to note since silence around fathers may contribute to lack of updates among people on what is acceptable behavior regarding fathers’ relationship to their children. Ideally, future research should combine such detailed studies on political parties with measures on activities in civil society such as pressure from women’s movements and/or father’s groups.

The analysis of this study is descriptive, but we have provided a basis for future causal analyses in the area of elite signaling where one particularly important takeaway regards how different fatherhood roles fluctuate over time (there are clear peaks in the data) and thus point to the need of employing dynamic models in studies on impact. Another takeaway is that scholars should be aware of difficulties regarding the possibility of sharply disentangling relationships between depictions of men as fathers in public documents, policymaking, and behavior. Our data is observational, but it shows how intertwined the various aspects of fatherhood are. For instance, we have demonstrated that many things coincided around 2002 in Sweden: a peak in the mentions of an active positive fatherhood role, an extension of non-transferable days in parental leave to 60 days, and a comparatively sharp increase of eight percentage points in the number of days in parental allowance used by fathers. Analyses have to be really sharp to pinpoint the exact causal steps in the chain between decisions, depictions, and behavior.

Finally, we end this study by alerting policymakers that language used when talking about men as fathers should be carefully considered. It may not only be men as fathers but also women as mothers who are affected by signals sent from how fathers are depicted in legislative texts. We are particularly thinking here of the presence of an active negative fatherhood role where the Wordify analysis painted a picture of a violent and abusive father that certainly needs to be circumscribed regarding his involvement with children and mothers. Importantly, LLMs facilitated analyses of material outside “traditional” areas of family policies which gives a more comprehensive picture of how fathers are talked about than what is usually the case.Footnote 14 On the one hand, abusive fathers need to be publicly discussed but on the other hand, people need to be constantly reminded of the positively engaged father. Indeed, elite signals help people update what is acceptable behavior, and there are reasons for policymakers who want to change fathers’ behavior to carefully consider the words used in parliamentary processes.

Appendix

Validity of ChatGPT Analysis

Questions on hallucinations arise mainly when large language models are asked to generate open-ended text. In our study the model never produces prose: it performs a narrowly defined classification task, selecting (and generating) one label from a small, closed set for each sentence already present in the parliamentary corpus. With the output space so constrained, the only possible failure mode is a mis-label (any fabricated content is counted as a mis-label). We quantified that risk on a 350-sentence validation set spanning three coding tasks: GPT-4’s labels agreed with human coders as well as the humans agreed with one another. To further minimize hallucination, we fixed the temperature parameter at 0, supplied 15 vetted examples via few-shot prompting, and automatically routed any non-conforming output to a default “not-applicable” category. Together, these design choices and empirical checks render hallucination immaterial for our application.

Prompt Used for Corpus-wide Coding

Below is the exact structure of the GPT-4 prompt that was used to classify every text extract from the parliamentary corpus, comprehensive of an instruction, a codebook, and 15 annotated examples to help GPT understand it:

Label the Swedish text according to how it describes the role of the father in the family.

Possible labels are:

-passive: this is a category that captures what is sometimes called the classical role given to and taken by fathers, which in essence is a role that does not include engaging with the child in person. Word used in theory might be “custodial parenthood”, “provider”, “breadwinner”, “process parenthood”. This is a person who is important in the life of the child but is not involved in the hands-on caring and upbringing. Society includes norms and sometimes creates clarifying policies around this father, for his sake, as well as for the sake of the child and the mother. Envisioned indicators might be words denoting the father being the moneymaker or provider, or someone who provides genes or sperm or overall protection or security.

-active_negative: this is a category that captures the negative roles of fathers, such as the oppressive father, the harsh and violent father, as well as neglecting father. Society needs to create policies around this father in order to restrict/stop him. Envisioned indicators are notions such as dangerous, punish (not educate or discipline in a non-aggressive way), aggressive, violent, oppressive, not paying child support.We also have three categories that capture the positive roles of fathers. Society needs to create policies around this father in order to encourage him. These categories are:

-active_positive_caring: this category focuses on what is stereotypically seen as the female parental role. Envisioned indicators would be words such as caring, warm, nurture, understanding, empathy, listening, comfort, confirming.

-active_positive_challenging: this category focuses on what is stereotypically seen as the male parental role. Envisioned indicators would be things like strengthening activity, risk-taking, daring, try your limits, sport, outgoing, education (including reading to child, which is one of the recurring activities in the data, where the father is seen to open the world to the child).

-active_positive_other: there are also other ways of being active as a father, and this category captures that. Most typically, this category indicates that the father is competent and reliable, and should be trusted with the child, but it does not single out why. Envisioned indicators are general references to competence, capability, responsibility, rights of and trust in fathers to handle information, take parental leave, get a parental allowance, be present in the life of the child, be an unspecified role model (“boys/girls need male role models”).

-not_applicable: not applicable.

Text: visserligen är det obalans i uttaget av föräldraförsäkringen, men samtidigt är det viktigt att slå fast att fler pappor i dag tar ut föräldraledighet än före införandet av mamma- och pappamånaden.

Label: active_positive_other

Text: ha föräldrar gemensamt barn i sin värd, utgår föräldrapenning över garanlinivån lill fadern endast under förutsättning att även modern är eller enligt vad förut sagts bort vara försäkrad för sjukpenning som överstiger garantinivån.

Label: passive

Text: i båda fallen är modern genetisk mor till barnet.

Label: not_applicable

Text: här uppmanas pappor också att ta ett ansvar som läsande fäder.

Label: active_positive_challenging

Text: i de fall socialnämnden inte tar sitt ansvar eller inte lyckas, måste det ändå finnas rätt för nära anhöriga, som mor- och farföräldrar, att hos tingsrätten föra talan om umgänge.

Label: not_applicable

Text: som förutsättning för alt barnavårdsnämnden skall vara skyldig att utreda om annan än den äkta mannen kan vara fader uppställer förslaget - utom att barnet skall ha viss anknytning till Sverige - dels att utredningen skall ha begärts av vårdnadshavare för barnet, d.v.s., normalt modern, eller av den äkta mannen, dels att det skall finnas lämpligt.

Label: passive

Text: bland dem fanns män, kvinnor och barn, unga och gamla, fäder och mödrar, söner och döttrar, makar och syskon.

Label: not_applicable

Text: lagutskottet har tidigare anfört att man anser att den nuvarande ordningen ger betryggande garantier för att det verkligen är den biologiske fadern och inte någon annan som fastställs som far till ett barn (0000/00:lu0).

Label: passive

Text: för att underlätta för framför allt fäder att öka sitt uttag av föräldrapenning föreslås att ersättningen utges med sjukpenningens belopp oberoende av den andre förälderns sjukpenning.

Label: active_positive_other

Text: det är fullt möjligt att kommunicera kring varför föräldraskapet så lätt upplevs som något som angår mamman mer än pappan, varför pappor kan känna sig som tillräckligt goda fäder trots ett mycket lågt uttag av föräldraledighet, varför mammor ofta tror att de är bättre på att läsa av barnet än vad pappor är, varför pappor uppfattas som hjältar när de gör samma sak som mammor gör av bara farten och tusen andra frågor som har att göra med föräldraskapet som bekönad position.

Label: active_positive_caring

Text: det finns en överrepresentation bland fäder med låg utbildning, låg inkomst och pappor med utländsk bakgrund.

Label: passive

Text: någon skyldighet att godkänna en utländsk dom om moderskap för barnets sociala eller genetiska mor, eller en utländsk dom om faderskap för en genetisk fars manliga partner, kan däremot inte utläsas av domstolens hittillsvarande praxis.

Label: passive

Text: av barnens svar kan man utläsa att mammor generellt har mer tid för sina barn oavsett i vilken utsträckning de bor med mamma, medan för barnen kan det ge mer tid med pappa när föräldrarna separerar än när de bor ihop under förutsättning att de minst bor halva tiden med pappan.

Label: active_positive_other

Text: det vanliga är sedan att våldtäktsmannen -- om det inte var fadern eller en nära släkting som förövat dådet -- betalar flickans föräldrar för att de inte skall anmäla fallet till polisen.

Label: active_negative

Text: om barnets föräldrar varken är gifta eller registrerade sammanboende vid barnets födelse är mamman ensam vårdnadshavare.

Label: passive

Text: genom projektet “läs för mig pappa”, knutet till arbetsplatsbibliotek, uppmuntras fäder att både läsa själva och att läsa för sina barn.

Label: active_positive_challenging

Text: då utmålas oftast pappan som hotfull, våldsam och som en dålig förälder.

Label: active_negative

Text: i isf:s rapport dubbeldagar – pappors väg in i föräldrapenningen dras slutsatsen att pappors uttag under barnets första levnadsår har ökat och att pappor som tidigare valt att ej ta ut föräldrapenning nu börjat ta ut dagar.

Label: active_positive_other

Text: [HERE, AFTER THE EXAMPLES, WE INSERTED THE NEW TEXT TO BE CLASSIFIED]

Rare deviations from the required output format were mapped to “not_applicable.” The use of a deterministic temperature (t = 0) and a closed label set eliminates the usual risk of hallucinated content.

For the other two annotation tasks, we used the exact same prompting structure, but the codebook changed. For the second task:

Possible labels are:

-implicit

-explicit

-not_applicable

For the third task:

Possible labels are:

-descriptive: if the sentence describes a state, like “we see that fathers are active”

-ideal: if the sentence is prescriptive, like “we wish for more active fathers”

-not_applicable: not applicable.

The 15 examples following the codebook in the prompt remain the same, but their labels change according to the taxonomy described in the codebook.

Empirical Validation Against Human Coders

A random set of 350 sentences was independently labeled by three authors (Humans 1–3) and by GPT-4 with the prompt above. Reliability is reported as Cohen’s κ, raw agreement (accuracy), and macro-F1 (percent). “Humans AVG” is the average pairwise agreement among the three annotators.

GPT-4 matches or outperforms the average human agreement on two of the three tasks and ties on the third. In other words, GPT-4 agrees more often with humans than humans agree with themselves on average, demonstrating human-level reliability for the coding scheme while avoiding inconsistencies typical of manual annotation.