Highlights

• Computed tomographic angiography (CTA) has potential in the early evaluation of suspected giant cell arteritis (GCA) patients.

• Presence of a blurred superficial temporal artery (STA) wall and associated perivascular enhancement on CTA may serve as a valuable diagnostic marker in assessment of GCA patients.

• CTA may have a diagnostic role in settings where access to advanced imaging modalities is limited.

Introduction

Giant Cell Arteritis (GCA) is the most common form of primary vasculitis in clinical practice. Its prevalence is particularly high among patients aged ≥50 years, with females experiencing this condition at a rate three times higher than males. Reference Pradeep and Smith1 One of the most critical aspects of managing GCA is the early initiation of treatment, as it can effectively prevent devastating complications such as visual loss. Reference Pradeep and Smith1 Diagnosing GCA accurately is paramount for timely intervention. The American College of Rheumatology has established diagnostic criteria, emphasizing age 50 or older as a fundamental requirement for GCA classification. Reference Ponte, Grayson and Robson2 Additionally, broader range of clinical features, including new onset headaches, superficial temporal artery (STA) abnormalities, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 50 mm/hr or higher and positive STA biopsy or STA halo sign on ultrasound, are each assigned specific weighted scores in these diagnostic criteria. Reference Ponte, Grayson and Robson2 However, advancements in imaging techniques have begun to play a prominent role in the clinical diagnosis of GCA, as recommended by the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) guidelines. Reference Dejaco, Ramiro and Duftner3 In fact, one of the overarching principles of the updated EULAR guideline is the importance of early imaging tests in the diagnosis of GCA. Reference Dejaco, Ramiro and Duftner3 Imaging is especially valuable when performed before or shortly after initiating therapy since glucocorticoids can rapidly diminish its sensitivity. Reference Dejaco, Ramiro and Duftner3

EULAR recommends ultrasound as the first-line imaging test for suspected GCA patients. Reference Dejaco, Ramiro and Duftner3 Ultrasound, specifically targeted at the temporal arteries, has been shown to be highly specific (99.5%) in detecting GCA when used in conjunction with clinical examination. Reference Schäfer, Jin and Schmidt4 In the acute setting, ultrasound can reveal a distinctive “halo sign,” signifying concentric hypoechoic wall swelling due to arterial wall inflammation. Reference Schäfer, Jin and Schmidt4 Furthermore, ultrasound can provide valuable intima-media thickness measurements of the scalp arteries, enabling differentiation between vasculitic and normal arteries in GCA. Reference Schäfer, Jin and Schmidt4 However, ultrasound has several limitations such as operator dependency and limited visualization of deep arteries. Reference Luqmani, Lee and Singh5

EULAR also recommends MRI as an alternative to ultrasound for patients with suspected GCA. Reference Dejaco, Ramiro and Bond6 Recent studies have demonstrated the sensitivity of MR vessel wall imaging in GCA diagnosis, with values ranging from 75.0% to 93.6%, depending on the study. Reference Klink, Geiger and Both7,Reference Rhéaume, Rebello and Pagnoux8 Despite the growing body of evidence supporting the use of MRI in GCA diagnosis, Reference Kwan, Islam, Tampieri and Ten Hove9 high-resolution MR imaging of the scalp arteries faces limitations for acute diagnosis and treatment, including accessibility and extended length of testing.

Other alternative imaging modalities used as part for diagnosis of GCA include Positron Emission Tomography (PET), particularly utilizing [18F] fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG), and Computed Tomography Angiography (CTA). The utility of FDG-PET is limited by nonspecific uptake in cells with high glucose metabolism and high background activity in several non-target organs. This complicates the interpretation of the images, leading to an increased number of false positive results. Reference Imfeld, Aschwanden and Rottenburger10 Additionally, PET isotopes that specifically target GCA are expensive, inaccessible in acute settings and are not recommended for immunocompromised patients. Reference Imfeld, Aschwanden and Rottenburger10

While literature on the usage of CTA in GCA is limited, a study by Lariviere et al. demonstrated the potential of CTA for diagnosing large vessel GCA, with sensitivity and specificity values of 73% and 78%, respectively. Reference Lariviere, Benali and Coustet11 CTA provides superior spatial resolution compared to MRI, potentially offering better visualization of inflammatory changes in the vessel wall, including the scalp arteries. A standard CTA of the head encompasses the visualization of extracranial carotid artery branches, a coverage extent akin to MRI. Additionally, CTA can be conducted rapidly in the acute setting, which is advantageous compared to the time-intensive nature of MRI or ultrasound.

In this study, we set out to investigate the association of CTA findings of the suspected GCA patients with GCA-positive STA biopsy results. Additionally, the study investigated alternative diagnoses for all the suspected GCA patients with GCA-negative STA biopsy results.

Methods

Study design and data collection

A retrospective review of patients who underwent temporal artery biopsy for suspected GCA at Kingston Health Sciences Centre between the years 2010 and 2018 was conducted. Inclusion criteria encompassed patients who had undergone a CT examination of the head within ± 2 weeks of the STA biopsy, with perivascular and mural enhancement assessed on the arterial-phase CT angiogram acquisitions. A total of 22 suspected GCA patients met the inclusion criteria. A GCA-positive STA biopsy result was defined as STA demonstrating histopathological evidence consistent with GCA, and negative STA biopsy result was defined as STA demonstrating histopathological results not consistent with GCA. Based on the STA biopsy results, obtained from the pathology reports, the patients were stratified into two groups: Positive and negative biopsy groups. Alternative diagnosis was also determined from chart reviews for the GCA-suspected patients with GCA-negative STA biopsy results.

The findings from the CTA images included blurred STA wall and perivascular enhancement. Additionally, we included the presence of stenosis or occlusion of STA and calcification. Reference Conway, Smyth and Kavanagh12 Baseline characteristics of the patients were also collected, including patient age, time of symptom onset, presenting symptoms, ESR, C-reactive protein (CRP) levels, details of treatment initiation and type, as well as the results of the STA biopsy.

Analysis

Two fellowship-trained neuroradiologists with expertise in vascular imaging assessed in a consensus-based manner, the bilateral superficial temporal arteries for imaging signs that included blurred STA wall and perivascular enhancement, stenosis or occlusion of STA and presence of calcifications.

To determine the relevance of observed imaging signs, odds ratio (OR) was calculated to assess the strength of association between CTA imaging signs and STA biopsy results. OR greater than 1 suggests a positive association between a particular imaging sign and positive STA biopsy result, i.e. the odds of having a positive STA biopsy for suspected GCA patients with the imaging sign are higher than those without the particular imaging sign.

Results

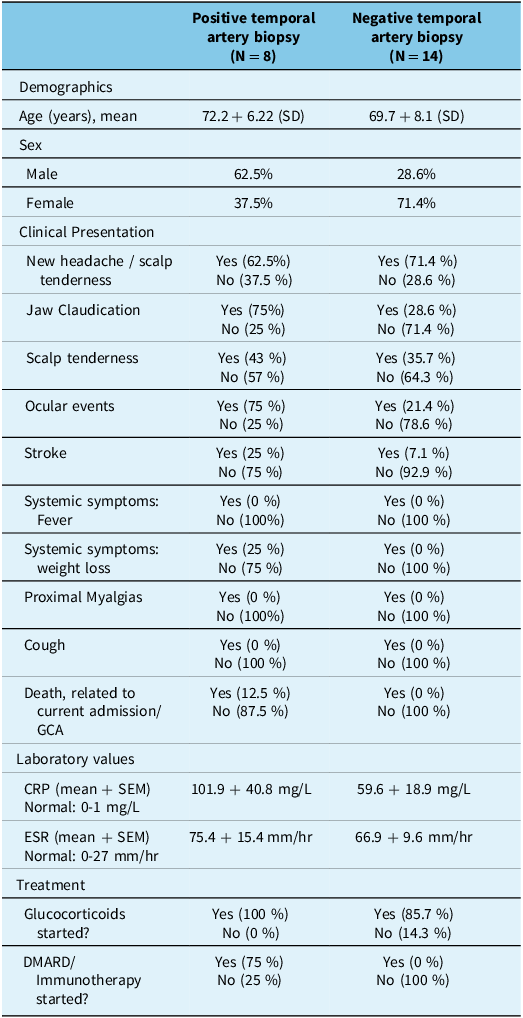

Baseline characteristics of the 8 patients with positive biopsy and 14 patients with negative biopsy results are outlined in Table 1. Mean age of patients with positive biopsy results was 72.2 years (SD = 6.22), with a higher proportion of males compared to females (62.5% vs 37.5%). In the biopsy-positive group, 62.5% reported new headache or scalp tenderness, and 75% had jaw claudication. Scalp tenderness was noted in 43% of cases, and 75% experienced ocular events. Stroke was observed in 25% of patients, likely secondary to GCA. Similar to the negative biopsy group, systemic symptoms (fever, weight loss) and proximal myalgias were absent in all cases. Laboratory findings revealed a mean CRP of 101.9 ± 40.8 mg/L and a mean ESR of 75.4 ± 15.4 mm/hr. All patients with positive biopsy results were initiated on glucocorticoid therapy, and 75% commenced disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) /Immunotherapy. The only statistically significant difference (p < 0.05) in baseline characteristics between the biopsy-positive and biopsy-negative cohorts was the initiation of DMARD/immunotherapy (p = 0.001, Fisher’s exact test). There was no significant difference in CRP or ESR levels between the groups based on Welch’s t-test.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of patients

GCA = Giant Cell Arteritis; CRP = C-reactive protein; ESR = Erythrocyte sedimentation rate; DMARD = Disease-modifying antirheumatic drug.

Mean age of patients with negative biopsy results was 69.7 years (SD = 8.1) and predominantly female composition (71.4%). In the biopsy-negative group, 71.4% reported new headache or scalp tenderness, while 28.6% experienced jaw claudication. Scalp tenderness was present in 35.7% of cases, and 21.4% had ocular events. Only 7.1% of patients experienced a stroke, likely unrelated to GCA. Laboratory values indicated a mean CRP of 59.6 ± 18.9 mg/L (normal: 0–1 mg/L) and a mean ESR of 66.9 + 9.6 mm/hr (normal: 0–27 mm/hr). Treatment records revealed that 85.7% of these patients had initiated glucocorticoid therapy, while none had started DMARDs/Immunotherapy.

A total of 16 patients were started on glucocorticoids. One patient was started by a family physician at an unknown date. Three patients were already on prednisone, either due to rheumatoid arthritis (RA) or polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR). Two patients were not started on glucocorticoids as both had negative temporal artery biopsies.

For the 16 patients who were started on glucocorticoids, the mean difference between the glucocorticoid start date and CTA date was −1.4 days (SD: 12.8 days), and the mean difference between the glucocorticoid start date and temporal artery biopsy was approximately −4.3 days (SD: 5.2 days). It should be noted that a negative value implies that glucocorticoids were started prior to both the biopsy and CT angiography.

Patients who were initially suspected of GCA but received negative results from a STA biopsy ultimately received a wide variety of final diagnoses as outlined in Figure 1. The alternative diagnosis included headache (n = 2), temporomandibular Joint (TMJ) (n = 1), glaucoma (n = 1), PMR (n = 1) and various other conditions.

Figure 1. Sankey diagram of initial main presenting symptom and final diagnosis or differential of patients with negative temporal artery biopsy (within 6 months from date of initial presentation).

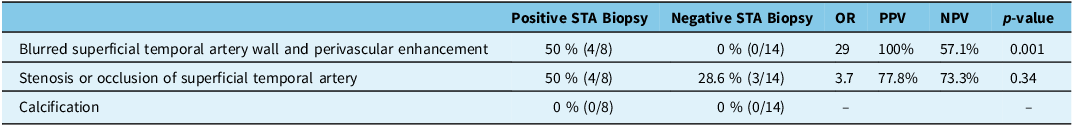

The CTA findings in patients with positive STA biopsy for GCA and those with negative STA biopsy results are outlined in Table 2. Both blurred STA wall and perivascular enhancement were observed in 50% of patients with positive STA biopsy results, while none of the patients with negative STA biopsy results displayed these findings (OR = 29, p = 0.001, positive predictive value (PPV) = 100%, negative predictive value (NPV) = 77.8%), suggestive of a strong positive association between these imaging signs and positive STA biopsy. A representative example of blurred STA wall and perivascular enhancement in one of the positive STA biopsy patients is shown in Figure 2. Stenosis or occlusion of the STA was more common in the positive biopsy group (50% vs. 28.6% in the negative biopsy group), although this difference was not statistically significant (OR = 3.7, p = 0.34, PPV = 57.1%, NPV = 73.3%). Finally, calcification was not observed in either group.

Figure 2. Representative sagittal CT angiography images for patients with positive superficial temporal artery (STA) biopsy for giant cell arteritis (GCA). (A–C) Blurred distal STA wall and associated perivascular enhancement.STA = Superficial temporal artery; GCA = Giant cell arteritis; CTA = Computed tomographic angiography; TIA = Transient Ischemic Attack.

Table 2. Comparison of computed tomographic angiography findings of patients with positive superficial temporal artery (STA) biopsy for giant cell arteritis (GCA) and patients with negative STA biopsy for GCA

STA = Superficial temporal artery; GCA = Giant cell arteritis; PPV = Positive predictive value; NPV = Negative predictive value; OR = Odds ratio.

Discussion

The pivotal role of timely and accurate diagnosis in managing GCA is essential to prevent severe complications. While traditional diagnostic criteria and methods, such as temporal artery biopsy, and more recently imaging such as MRI and ultrasound, become standard in clinical practice, the evolution and widespread use of CTA has the potential for the early assessment of suspected GCA patients. Our study provides radiological-pathological evidence that CTA can be used for assessment of inflammatory changes in the STA and thus play a role in the diagnostic pathway of suspected GCA patients.

The CTA analysis in this study identifies some CTA abnormalities in 50% (4/8) of biopsy-confirmed GCA patients. These abnormalities included blurred distal STA wall and associated perivascular enhancement, as depicted in Figure 2, which was only seen in 50% of patients with positive GCA biopsy. Consequently, the presence of a blurred distal STA wall and associated perivascular enhancement may serve as a valuable diagnostic sign in the assessment of suspected GCA patients, as it significantly increases the likelihood of positive STA biopsy and subsequent GCA diagnosis in correct clinical scenario (OR = 29, p = 0.001).

Another CTA sign, stenosis or occlusion of the STA, was also identified in the 50% (4/8) of the patients with a positive STA biopsy and 28% of those with a negative STA biopsy. However, this difference did not achieve statistical significance (OR = 3.7, p = 0.34). This aligns with prior findings, which indicated that ultrasound also revealed stenosis and occlusion to be nonspecific findings in imaging. Reference Monti, Floris and Ponte13 Finally, calcification was not observed in any of the patients, suggesting that it may not serve a role as an imaging marker in the diagnosis of GCA.

A similar study was conducted by Conway et al., which investigated the association of CTA signs with STA biopsy results and also found blurred STA wall and perivascular enhancement to be associated with eventual diagnosis of GCA. Reference Conway, Smyth and Kavanagh12 Our study is consistent with these findings and extends beyond the CTA signs and provides a comprehensive analysis of presenting symptoms, laboratory values and alternative diagnosis for all the patients with negative STA biopsy results.

Comparing CTA with traditional diagnostic methods and other imaging techniques, it is evident that each modality brings unique advantages and limitations. While ultrasound has been lauded for its non-invasive nature and high specificity, its limitations, such as operator dependency and restricted visualization of deep arteries, cannot be ignored. A study evaluating inter-rater analysis for ultrasounds showed that there was only moderate agreement among GCA sonographers with an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.61, 95% CI. Reference Luqmani, Lee and Singh5 Similarly, MRI, despite its sensitivity and ability to visualize inflammatory changes in vessel walls, is hampered by its accessibility and extended testing duration, particularly in acute settings. CTA, with its rapid testing capability and less operator dependency, addresses some of these limitations, albeit with its own set of challenges and considerations, such as radiation exposure. The timing of imaging is paramount, as changes may dissipate rapidly following the administration of glucocorticoids. This could result in misdiagnosis upon a negative imaging result, leading to a lack of follow-up for the false-negative GCA patients. Reference Rhéaume, Rebello and Pagnoux8

The spectrum of final diagnoses, especially in patients presenting with GCA-like symptoms but yielding negative biopsy results, underscores the diagnostic challenges in clinical practice. The results of this study found at least ten unique non-GCA diagnoses for symptoms that present very similarly to GCA. While combining multiple diagnostic imaging modalities might increase the sensitivity of testing for GCA, Reference Codes-Mendez, Moya and Park14 it would be resource-intensive, in terms of time, money and personnel.

While the findings of this study are promising and consistent with the literature, it is crucial to acknowledge its limitations, including the retrospective nature and a small sample size. Due to small sample size, this study is not powered to detect smaller associations of CTA signs with GCA diagnosis. This study was also limited to a single institution, but the results can be generalized to other institutions with availability of CTA imaging. We also acknowledge that expertise of neuroradiologists at our institution may not be generalizable to neuroradiologists at other centers or general radiologists working in community settings. Furthermore, imaging interpretation was performed using a consensus-based approach rather than independent blinded reads, precluding assessment of interobserver agreement.

In conclusion, this study highlights the potential advantageous role of CTA in the initial assessment of suspected GCA patients with diverse clinical symptomatology, thereby aiding in timely diagnosis.

Acknowledgments

None.

Author contributions

A.R., S.B. and B.K. contributed to the conceptualization and design of the study. A.R. was responsible for data collection and analysis. A.R. and S.K. drafted the initial manuscript. O.I., J.R., S.B., B.K. and M.T.H. critically reviewed and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors have reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding statement

There is no funding to report.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest related to the content of this article.

Target article

CT Angiography of the Head for the Initial Assessment of Giant Cell Arteritis: Presenting Symptoms, Biopsy Outcomes and Alternative Diagnosis

Related commentaries (1)

Reviewer Comment on Rizwan et al. “CT Angiography of the Head for the Initial Assessment of Giant Cell Arteritis: Presenting Symptoms, Biopsy Outcomes and Alternative Diagnosis”