Introduction

Catostomidae (suckers) is a diverse group of freshwater fishes within Cypriniformes, distributed across the Holarctic region, with a pronounced concentration of species in North America and limited representation in eastern Asia. The family comprises 86 species across 15 genera, with 85 species (14 genera) occurring in North America (Fricke et al. Reference Fricke, Eschmeyer and Fong2024a), making Catostomidae the third-largest group of freshwater fishes on the continent (Warren et al. Reference Warren, Burr, Walsh, Bart, Cashner, Etnier, Freeman, Kuhajda, Mayden, Robison, Ross and Starnes2000; Harris and Mayden Reference Harris and Mayden2001). Catostomids are traditionally classified into 4 subfamilies: Myxocyprininae, Cycleptinae, Ictiobinae and Catostominae, the latter of which includes several recognized tribes such as Catostomini, Moxostomatini, Thoburniini and Erimyzonini (Nelson Reference Nelson2006). Recent molecular phylogenetic analyses confirmed the monophyly of Catostomidae but revealed conflicting relationships among lineages depending on the type of dataset used (nuclear, mitochondrial) (e.g. Harris and Mayden Reference Harris and Mayden2001; Sun et al. Reference Sun, Xie, Wang, Liu, Treer and Chang2007; Doosey et al. Reference Doosey, Bart, Saitoh and Miya2010; Chen and Mayden Reference Chen and Mayden2012; Bagley et al. Reference Bagley, Mayden and Harris2018; Yang et al. Reference Yang, Mayden and Naylor2024). Although this family is almost exclusively native to North America, Catostomus catostomus is the only species with a disjunct distribution across the North Pacific region, occurring in both the Nearctic and the Siberian part of the Palearctic region (Harris et al. Reference Harris, Hubbard, Sandel, Warren and Burr2014). In contrast, Myxocyprinus asiaticus is the only catostomid species endemic to Eurasia, occurring in the Yangtze River basin in China (Smith Reference Smith and Mayden1992). The high species richness and distribution of Catostomidae across the Holarctic region, along with their well-studied phylogenetic background (e.g. Chen and Mayden Reference Chen and Mayden2012; Bagley et al. Reference Bagley, Mayden and Harris2018; Yang et al. Reference Yang, Mayden and Naylor2024), make this fish group a suitable model for exploring evolutionary and biogeographic patterns of their parasites and for studies of host–parasite diversification.

As exclusive hosts of Pseudomurraytrematidae (Platyhelminthes: Monopisthocotyla), catostomids provide a unique opportunity to investigate parasite diversification and host–parasite coevolution within a well-defined and geographically structured host lineages. Given the generally narrow host specificity observed in many monopisthocotylans and their frequently co-distributed evolutionary history with hosts, these ectoparasites represent powerful tools for exploring the biogeographic patterns of host lineages and serve as valuable phylogenetic markers in comparative and cophylogenetic studies of host–parasite systems (e.g. Benovics et al. Reference Benovics, Desdevises, Vukić, Šanda and Šimková2018; Šimková et al. Reference Šimková, Řehulková, Choudhury and Seifertová2022; Šimková Reference Šimková2024).

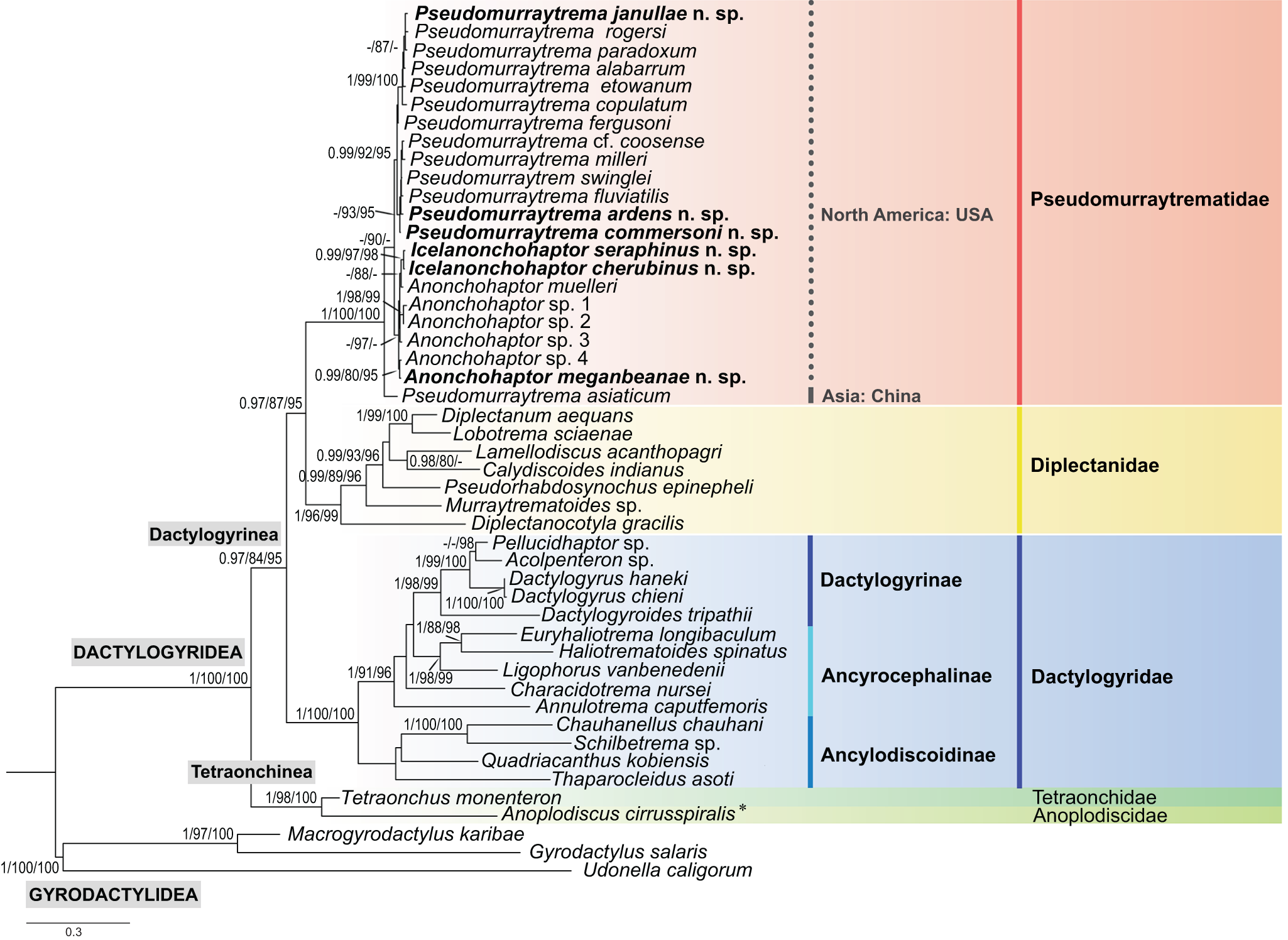

Pseudomurraytrematidae was initially established as a subfamily within Dactylogyridae by Kritsky et al. (Reference Kritsky, Mizelle and Bilqees1978) and was later elevated to family status within Dactylogyrinea by Beverley-Burton (Reference Beverley-Burton, Margolis and Kabata1984). This taxonomic rank was primarily based on the distinctive morphology of the reproductive system, first noted by Leiby et al. (Reference Leiby, Kritsky and Peterson1972) in 4 genera: Anonchohaptor Mueller, 1938, Icelanonchohaptor Leiby, Kritsky & Peterson, 1972, Myzotrema Rogers, 1967 and Pseudomurraytrema Bychowsky, 1957. The phylogenetic position of Pseudomurraytrematidae within Monopisthocotyla remains unresolved, as the family has been underrepresented in both morphological and molecular studies. Previous morphological analyses, which included only 4 species of Pseudomurraytrema (P. copulatum, P. etowanum, P. paradoxum and P. rogersi), suggested a close phylogenetic relationship between Pseudomurraytrematidae and Diplectanidae within Dactylogyrinea (Kritsky and Boeger Reference Kritsky and Boeger1989; Boeger and Kritsky Reference Boeger and Kritsky1993, Reference Boeger and Kritsky1997, Reference Boeger, Kritsky, Littlewood and Bray2001). Molecular data for this family are even scarcer. Only 1 unidentified species of Pseudomurraytrema (= P. ardens sensu Littlewood, Rohde & Clouth, Reference Littlewood, Rohde and Clough1998; treated as a nomen nudum by Boeger et al. Reference Boeger, Kritsky, Domingues and Bueno-Silva2014) has been included in molecular analyses. Several studies suggested that Pseudomurraytrematidae might be a sister group either to Diplectanidae alone or to both Diplectanidae and Dactylogyridae within Dactylogyrinea (Littlewood et al. Reference Littlewood, Rohde and Clough1998; Olson and Littlewood Reference Olson and Littlewood2002; Bentz et al. Reference Bentz, Combes, Euzet, Riutord and Verneau2003; Šimková et al. Reference Šimková, Plaisance, Matějusová, Morand and Verneau2003; Plaisance et al. Reference Plaisance, Littlewood, Olson and Morand2005; Boeger et al. Reference Boeger, Kritsky, Domingues and Bueno-Silva2014; Ogawa and Itoh Reference Ogawa and Itoh2017; Moreira et al. Reference Moreira, Luque and Šimková2019; Soares et al. Reference Soares, Domingues and Adriano2021). These findings highlight the need for more comprehensive and robust morphological and molecular analyses to resolve the phylogenetic relationships and evolutionary history of Pseudomurraytrematidae.

All known members of Pseudomurraytrematidae are parasitic on the gills and/or skin of catostomid fishes (Catostomoidei, Cypriniformes). The family currently comprises 20 nominal species distributed across 4 genera: Anonchohaptor, Icelanonchohaptor, Myzotrema and Pseudomurraytrema. The latter genus is the type genus and contains 12 species, of which 11 occur in North America and only 1 in China (P. asiaticum Chang & Ji, Reference Chang and Ji1978 on Myxocyprinus asiaticus) (Chang and Ji Reference Chang and Ji1978; Kuchta et al. Reference Kuchta, Řehulková, Francová, Scholz, Morand and Šimková2020; McAllister et al. Reference McAllister, Leis, Cloutman, Woodyard, Camus and Robison2022). Anonchohaptor and Icelanonchohaptor include 3 and 4 species, respectively, all reported from North America (Kuchta et al. Reference Kuchta, Řehulková, Francová, Scholz, Morand and Šimková2020; Mendoza-Franco et al. Reference Mendoza-Franco, Hernández-Gómez and Caspeta-Mandujano2023). Myzotrema is monotypic, with Myzotrema cyclepti described by Rogers (Reference Rogers1967) on Cycleptus elongatus (Cycleptinae) from Alabama. Host associations within Pseudomurraytrematidae differ among genera, with species of Anonchohaptor infecting multiple catostomid subfamilies, while species of Pseudomurraytrema and Icelanonchohaptor appear more host-restricted. However, the overall diversity and host specificity of these parasites remain poorly understood due to limited sampling across host taxa and regions (Mergo and White Reference Mergo and White1984; Kuchta et al. Reference Kuchta, Řehulková, Francová, Scholz, Morand and Šimková2020).

A survey aimed at investigating the diversity of monopisthocotylans parasitizing North American catostomid fishes was initiated in 2018. To date, 16 catostomid species have been examined across 8 US states, the Canadian province of Québec and 3 northern Mexican states. The first results of this effort reported 3 species of Dactylogyrus (Dactylogyridae) and 4 species of Gyrodactylus (Gyrodactylidae) infecting Hypentelium nigricans, Catostomus catostomus and Catostomus commersonii from Arkansas, New York and Québec (Šimková et al. Reference Šimková, Řehulková, Choudhury and Seifertová2022; Rahmouni et al. Reference Rahmouni, Seifertová and Šimková2023; Řehulková et al. Reference Řehulková, Seifertová, Francová and Šimková2023). As a continuation of this work, the present study focuses on members of Pseudomurraytrematidae collected from the catostomid hosts. The objectives are: (i) to identify and characterize newly collected pseudomurraytrematids, (ii) to compare their diversity with previous records and (iii) to reveal evolutionary relationships within Pseudomurraytrematidae and its placement within Dactylogyridea using an integrative approach.

Materials and methods

Collection and identification of fish hosts

A total of 16 catostomid species (Catostominae, Ictiobinae) were captured by electrofishing or seine nets from several localities in 8 US states (i.e. Arkansas, Illinois, Michigan, Mississippi, New York, Oregon, Texas and Wisconsin), the Canadian province of Québec and 3 northern Mexican states (Chihuahua, Coahuila and Durango). The fieldwork was carried out under permission from the relevant local authorities (provided by the US partners listed in the Acknowledgements). Fishes were initially identified by local experts well-versed in the regional ichthyofauna. This preliminary identification was later verified through cytochrome b (cyt b) mitochondrial gene sequencing. The taxonomic nomenclature and classification adopted in this study are in accordance with Eschmeyer’s Catalog of Fishes (Fricke et al. Reference Fricke, Eschmeyer and van der Laan2024b). Where original host names differ from the currently accepted ones, the original names are given in parentheses as synonyms. Live fishes were transported to the lab and housed in oxygenated containers. Within 3 days of capture, they were euthanized via spinal cord transection for immediate parasitological examination.

Collection and preparation of parasites

Skin scrapings, fins and gills were removed from the host, placed in Petri dishes with tap water and examined using a stereomicroscope (Olympus SZX7, Tokyo, Japan) to detect parasites. Live pseudomurraytrematids were individually removed from host tissues using fine needles and immediately processed for morphological (see Řehulková and Gelnar Reference Řehulková and Gelnar2005) and molecular analyses. To draw and measure their hard structures (i.e. haptoral attachment structures, male copulatory organ and vagina), parasites were thoroughly pressed and preserved in a solution of glycerine and ammonium picrate (GAP; Malmberg Reference Malmberg1957). After morphometric examination, these GAP-fixed specimens were re-mounted in Canada balsam to ensure their long-term preservation (Ergens Reference Ergens1969). Some worms were fixed in 70% ethanol prior to staining with iron acetocarmine or Gomori’s trichrome, dehydration and mounting to allow examination of their internal structures. For DNA analysis, specimens were bisected with fine needles and then one half of the body (either the posterior part containing haptoral sclerites or the anterior part with the male copulatory organ and vagina) was fixed in 96% ethanol to facilitate future DNA extraction; the other half was mounted on a slide, fixed with GAP for species identification, and kept as a hologenophore (sensu Pleijel et al. Reference Pleijel, Jondelius, Norlinder, Nygren, Oxelman, Schander, Sundberg and Thollesson2008). The mounted parasites were studied using an Olympus BX61 microscope (Tokyo, Japan) equipped with phase contrast optics. Illustrations were created using a drawing attachment, scanned and redrawn using a graphics tablet (Wacom Intuos5 Touch) compatible with Adobe Illustrator software (Adobe Systems Inc., San Jose, CA, USA). Measurements (given in micrometres) were taken using an Olympus digital camera coupled with Stream Motion 1.9.2 image analysis software (Olympus) and are reported as the mean, with the range and number (n) of specimens measured in parentheses. The numbering of hook pairs follows the method recommended by Mizelle (Reference Mizelle1936). The male copulatory organ is henceforth abbreviated to MCO. Type and voucher specimens of parasites examined during the present study were deposited in the Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of Natural History (USNM), Washington, DC, USA, as indicated in the respective species accounts.

DNA extraction, amplification and sequencing

Bisected parasite specimens preserved in 96% ethanol were dried using a centrifugal vacuum concentrator (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). DNA was extracted using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following the protocol for the purification of total DNA from animal tissues. A fragment spanning partial 18S rDNA and the internal transcribed spacer (18S–ITS1) and a fragment of partial 28S rDNA (28S) were amplified and sequenced. A list of primers and PCR conditions are provided in Table 1. Amplifications were carried out in a 20 μL reaction mixture containing 13 μL nuclease-free water, 4 μL FIREPol Master Mix Ready to Load (Solis BioDyne, Tartu, Estonia), 0.5 μL of each primer (10 μM concentration), and 2 μL of eluted DNA. PCR products were detected by electrophoresis in 1.5% agarose gels stained with GoodView (SBS Genetech, Bratislava, Slovakia). Amplified products were purified using EPPiC Fast (Amplia, Bratislava, Slovakia), following the manufacturer’s protocol. Sequencing was performed in both directions using PCR primers with the BigDye® Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Prague, Czech Republic) on an ABI Prism 3130 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). Raw sequencing data were analysed using Sequencing Analysis software v.5.2 (Applied Biosystems) and processed with Sequencer software (Gene Codes Corporation, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) to assemble contigs. Newly obtained sequences have been deposited in GenBank (accession numbers are listed in Table 3).

Table 1. List of primers used for PCR amplification of nuclear rDNA markers in the present study

Table 2. Monopisthocotylan species included in the phylogenetic analyses, with their family assignment, corresponding host taxa (species, family, order), country of origin and GenBank accession numbers (28S rDNA)

Table 3. Pseudomurraytrematid species from catostomid hosts in North America, with site of infection, host taxa (species, subfamily/tribe), locality and GenBank accession numbers (28S rDNA, 18S–ITS1). N – number of specimens molecularly analysed

Phylogenetic analyses

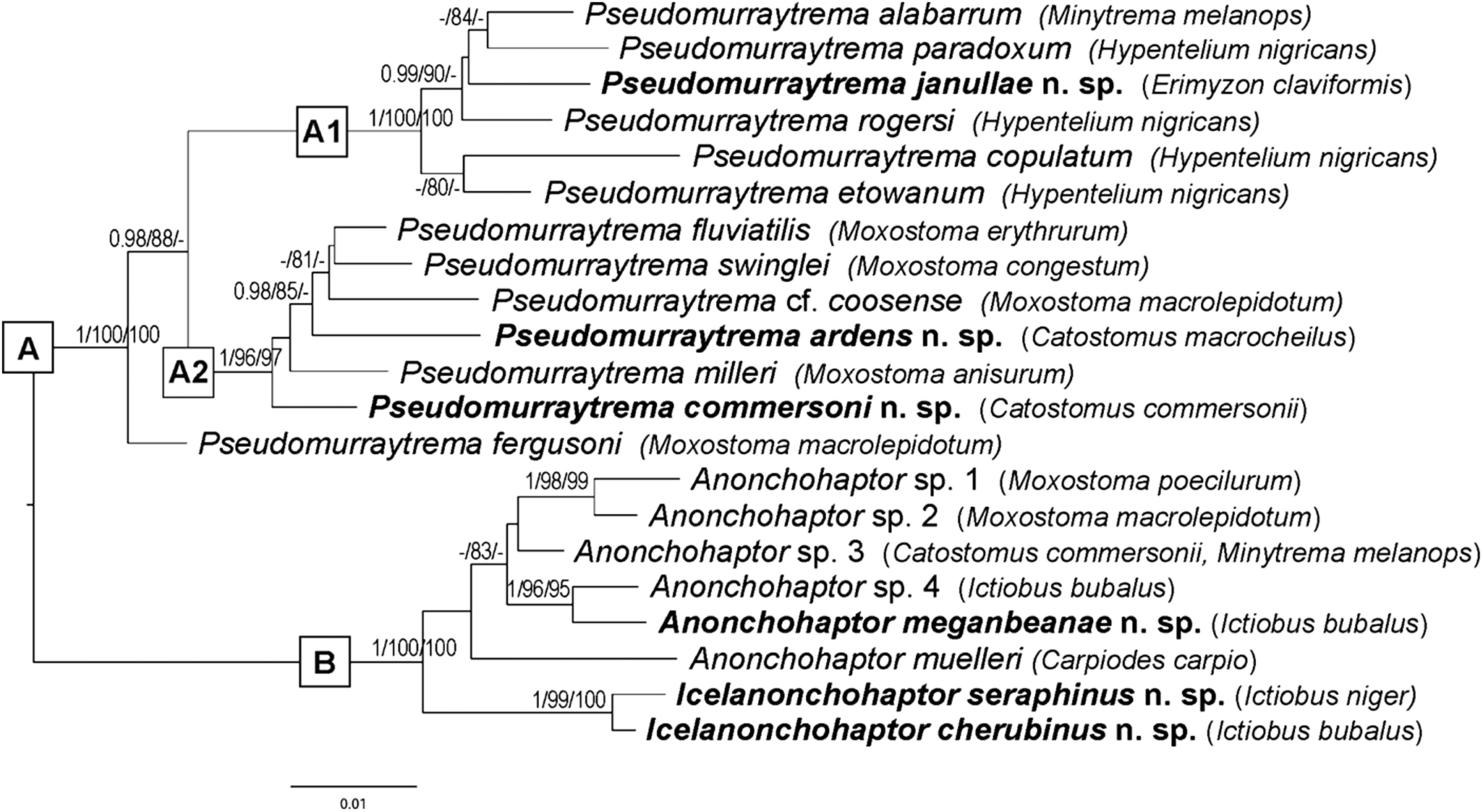

To infer the phylogenetic relationships among species of Pseudomurraytrematidae, 2 datasets were compiled: a single-gene dataset (28S rDNA) and a concatenated dataset comprising 18S rDNA, ITS1 and 28S rDNA sequences. The 28S dataset included 13 sequences of Pseudomurraytrema species, 2 species of Icelanonchohaptor and 6 species of Anonchohaptor newly sequenced in the present study, as well as 1 sequence of P. asiaticum from Myxocyprinus asiaticus (China). In addition, 21 sequences of selected representatives from Diplectanidae, Dactylogyridae, Tetraonchus monenteron and Anoplodiscus cirrusspiralis were retrieved from GenBank. Representatives of Gyrodactylidea were used as outgroups. Accession numbers, host species and locality data for the 28S dataset are listed in Table 2. The concatenated dataset (18S, ITS1 and 28S) was restricted to Nearctic Pseudomurraytrematidae and included 21 sequences representing the species examined in the present study. Accession numbers, host species and locality data are provided in Table 3.

The Maximum Likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI) algorithms were used to build the phylogenetic trees. Sequence alignments were performed on the MAFFT v.7 server (https://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/server/) (Katoh et al. Reference Katoh, Rozewicki and Yamada2019) using the G-INS-i algorithm. The best-fit sequence substitution models were determined based on the Bayesian information criterion using ModelFinder (Kalyaanamoorthy et al. Reference Kalyaanamoorthy, Minh, Wong, von Haeseler and Jermiin2017) implemented in IQ-TREE (Nguyen et al. Reference Nguyen, Schmidt, von Haeseler and Minh2015). The TIM3 + F + I + G4 model was chosen for the 28S dataset, while the K2P + I (18S), TIM2 + F + G4 (ITS1) and TPM2 + F + I (28S) models were selected for the concatenated dataset. The ML analyses were conducted using IQ-TREE (Nguyen et al. Reference Nguyen, Schmidt, von Haeseler and Minh2015) on the IQ-TREE web server (Trifinopoulos et al. Reference Trifinopoulos, Nguyen, von Haeseler and Minh2016). Branch supports were calculated using both the ultrafast bootstrap approximation (UFBoot; Hoang et al. Reference Hoang, Chernomor, von Haeseler, Minh and Vinh2018) and the Shimodaira–Hasegawa-like approximate likelihood ratio test (SH-aLRT; Guindon et al. Reference Guindon, Dufayard, Lefort, Anisimova, Hordijk and Gascuel2010) with 1000 replicates. UFBoot values ≥95% can be considered strong support, while values <80% should be treated with caution (Hoang et al. Reference Hoang, Chernomor, von Haeseler, Minh and Vinh2018). UFBoot provides nearly unbiased estimates of branch support, while SH-aLRT is more conservative. Each branch is assigned with SH-aLRT and UFBoot supports (Minh et al. Reference Minh, Lanfear, Wong, Ly-Trong, Trifinopoulos, Schrempf and Schmidt2025). Combining both tests (e.g. UFBoot ≥ 95 and SH-aLRT ≥ 80) provides reliable support for branches, while a discrepancy between them may indicate model errors or polytomies.

The BI analysis was conducted using MrBayes v.3.2 (Ronquist et al. Reference Ronquist, Teslenko, van der Mark, Ayres, Darling, Höhna, Larget, Liu, Suchard and Huelsenbeck2012) with the following Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) settings: 4 simultaneously running chains (1 cold and 3 heated), 5 million generations with a sampling frequency of every 100 generations, and a burn-in fraction of 25%. Posterior probabilities (PP) higher than 0.95 are generally considered to be strong support for a given clade, while values between 0.80 and 0.95 indicate weaker or moderate support, and values below 0.80 are usually considered unsupported. Convergence of the MCMC chains was assessed by examining the Potential Scale Reduction Factor (PSRF), which was close to 1.0 for all parameters, and by calculating Effective Sample Sizes (ESS) using Tracer v1.7 (Rambaut et al. Reference Rambaut, Drummond, Xie, Baele and Suchard2018), all of which exceeded 200. The obtained trees for BL and ML were visualized in FigTree v.1.4.3 (Rambaut, Reference Rambaut2017) and edited in Adobe Photoshop. The uncorrected pairwise genetic distances (p-distance) between the taxa were estimated using the software MEGA11 (Tamura et al. Reference Tamura, Stecher and Kumar2021) separately for each genetic marker.

Results

Fourteen of the 16 examined catostomid species were found to host pseudomurraytrematid parasites. Only Carpiodes cyprinus from Wisconsin (1 specimen examined) and Pantosteus nebuliferus from Mexico (20 specimens examined) were uninfected. Representatives of Pseudomurraytrematidae were recorded in all surveyed regions except Mexico, New York and Québec. In total, 22 monopisthocotylan species across 3 genera – Anonchohaptor, Icelanonchohaptor and Pseudomurraytrema – were collected from the gills or fins of the catostomid hosts. Pseudomurraytrema was the most species-rich genus (14 species), followed by Anonchohaptor (6 species) and Icelanonchohaptor (2 species). The highest parasite diversity was observed on Hypentelium nigricans (Arkansas), which harboured 4 species of Pseudomurraytrema (P. copulatum, P. etowanum, P. paradoxum, P. rogersi). Ictiobus bubalus hosted 2 Anonchohaptor species (Illinois, Texas) and 1 Icelanonchohaptor species (Mississippi). Most pseudomurraytrematid species were recovered from gills; only Icelanonchohaptor cherubinus n. sp. and Icelanonchohaptor seraphinus n. sp. were found on the fins of I. bubalus and I. niger, respectively (Mississippi).

Pseudomurraytrematidae Kritsky, Mizelle & Bilqees, 1978

Dactylogyridea Bychowsky, 1937

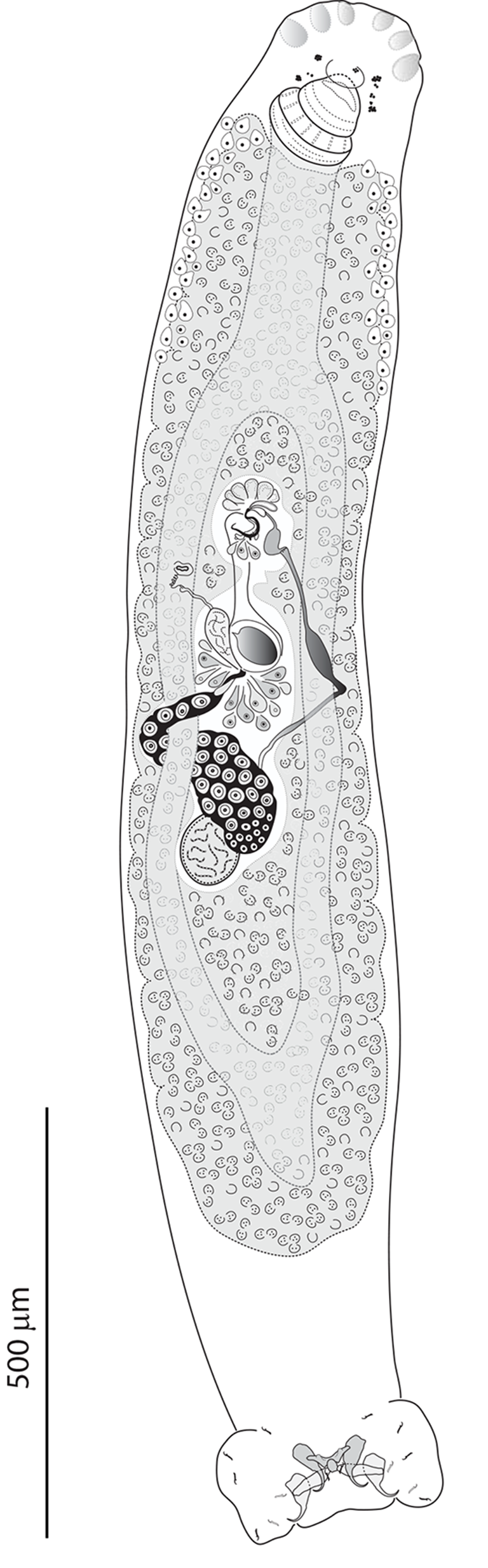

Diagnosis: Body divisible into cephalic region, trunk, peduncle and haptor. Tegument thin, smooth. Cephalic region developed into cephalic lappets or lobes; cephalic glands unicellular, arranged in 2 bilateral groups in the anterolateral trunk. Two pairs of irregular eyespots. Mouth subterminal and midventral. Pharynx muscular, glandular. Oesophagus short or elongated. Intestinal caeca 2, terminating blindly or confluent, lacking diverticula. Gonads in tandem, slightly overlapping; testis postovarian. Vas deferens looping around the left intestinal caecum; seminal vesicle an expansion of vas deferens. One or 2 prostatic reservoirs. MCO consisting of a U-shaped copulatory tube, basally articulated with a 3-ramous accessory piece (exceptionally modified as a whole in Pseudomurraytrema fergusoni). Ovary elongate, looping around the right intestinal caecum. Vagina dextroventral, consisting of a distal lightly sclerotized funnel and a proximal coiled portion (exceptionally modified as a whole in P. fergusoni). Seminal receptacle preovarian. Peduncle short or elongated. Haptor disc-shaped, cup-shaped, or polygonal. Haptoral structures comprising 14 hooks and, when present, 2 anchor-bar complexes (1 ventral, 1 dorsal). Each complex consisting of a pair of anchors supported by a bar. Anchors without defined roots. Ventral bar single; dorsal bar either single or paired. Parasites of catostomid fishes (Catostomoidei).

Genera included: Anonchohaptor Mueller, 1938; Icelanonchohaptor Leiby, Kritsky & Peterson, 1972; Myzotrema Rogers, 1967; Pseudomurraytrema Bychowsky, 1957 (type genus).

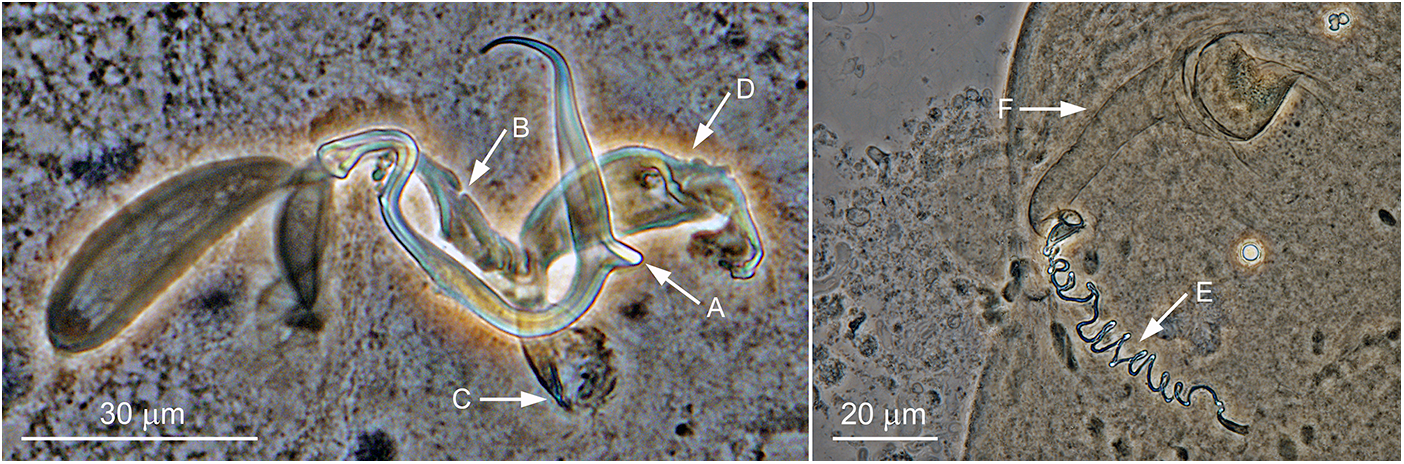

Remarks: The main taxonomic criterion for distinguishing between genera of this family is the shape and structure of the anterior (prohaptor) and posterior (haptor) attachment organs (Leiby et al. Reference Leiby, Kritsky and Peterson1972; Kritsky et al. Reference Kritsky, Mizelle and Bilqees1978; Beverley-Burton Reference Beverley-Burton, Margolis and Kabata1984). In species of Anonchohaptor and Icelanonchohaptor, the prohaptor resembles the triangular head of free-living Platyhelminthes (e.g. Dugesia) and bears 2 bilateral lappets, which appear less developed in species of Icelanonchohaptor compared to those of Anonchohaptor (Beverley-Burton Reference Beverley-Burton, Margolis and Kabata1984; as confirmed by the present study; see Figure 1A, B). In contrast, the prohaptor in Myzotrema and Pseudomurraytrema consists of cephalic lobes (Rogers Reference Rogers1967; Beverley-Burton Reference Beverley-Burton, Margolis and Kabata1984; present study, Figure 1C), similar to those observed in diplectanids and dactylogyrids. While the prohaptor is largely similar in Anonchohaptor and Icelanonchohaptor, the overall morphology and size of the haptor provide more reliable features for distinguishing these genera. Our study confirms the diagnostic characteristics outlined by Beverley-Burton (Reference Beverley-Burton, Margolis and Kabata1984), indicating that the haptor in Anonchohaptor is disc-shaped, notably wider than the body diameter, and slightly muscular, whereas in Icelanonchohaptor, it is cup-shaped, approximately the same diameter as the body, and strongly muscular (Figure 1A, B). With regard to the configuration of the haptoral sclerotized structures, species of all genera within Pseudomurraytrematidae possess 7 pairs of hooks. However, a fully developed ventral and dorsal anchor–bar complex is present only in species of Pseudomurraytrema (Figure 1C) and in the monotypic Myzotrema. In Pseudomurraytrema species, the dorsal bar is a paired structure, in contrast to a single bar observed in Myzotrema cyclepti (Rogers Reference Rogers1967). The presence or absence of the anchor–bar complexes appears to be a crucial trait for differentiating species of the 2 aforementioned genera from those of Anonchohaptor and Icelanonchohaptor. Species within Pseudomurraytrematidae generally share a conserved internal anatomy and, in particular, a basic structure of the MCO and vagina, with the exception of P. fergusoni (see Remarks to the species). The MCO consists of a copulatory tube supported by a 3-armed accessory piece (Figure 2). The copulatory tube is U-shaped (resembling a lyre). Its proximal portion is S-shaped, formed by 2 opposing curvatures, while the distal portion is narrowed. The 2 parts are separated by a submedial spine (Figure 2A). Among species, variation is observed in the thickness of the tube, the degree and position of the curves, and the form of the distal end. In P. fergusoni, the distal end of the copulatory tube is truncated, and the base fuses with the accessory piece to form a bulbous structure. Moreover, the vagina of P. fergusoni lacks the coiled proximal portion that characterizes all other known species of the family (typical morphology shown in Figure 2E, F).

Figure 1. Photomicrographs of stained specimens representing 3 genera of Pseudomurraytrematidae. A – Anonchohaptor meganbeanae n. sp. ex Ictiobus bubalus (Texas); B – Icelanonchohaptor cherubinus n. sp. ex Ictiobus bubalus (Mississippi); C – Pseudomurraytrema rogersi – mating pair ex Hypentelium nigricans (Arkansas). Diagnostic features distinguishing these genera are labelled in the image and correspond to characters used in the identification key.

Figure 2. Photomicrographs of the MCO (Pseudomurraytrema alabarrum) and vagina (Icelanonchohaptor seraphinus n. sp.). A: submedial spine demarcating the proximal and distal parts of the copulatory tube; B–D: arms of the accessory piece (proximal, medial and distal, respectively); E: multiply coiled proximal portion of the vagina; F: pouch-like distal portion of the vagina. These photomicrographs illustrate the typical morphology of the MCO and vagina in members of Pseudomurraytrematidae.

Species identification of pseudomurraytrematids is based primarily on the morphology and size of the haptoral hard structures and the distal parts of the reproductive system (i.e. MCO and vagina). However, existing taxonomic works on these parasites often lack consistency in representing all these structures, frequently omitting comprehensive details of the hook(s) and/or vagina. This lack of detail, combined with oversimplified depictions of the MCO, complicates accurate species delimitation – particularly within Anonchohaptor and Icelanonchohaptor, where the haptor bears only hooks.

Key to genera of Pseudomurraytrematidae

1. (2) Haptor with 7 pairs of hooks ………………………………………………………………………………………………. 3

2. (1) Haptor with 7 pairs of hooks, dorsal and ventral anchor-bar complexes — each with a pair of anchors without differentiated roots, and a single bar ……………………………………….... 5

3. (4) Haptor wider than the peduncle, disc-shaped, slightly muscular ……………………………………………………………….…………………………........... Anonchohaptor (Figure 1A)

4. (3) Haptor as wide as the peduncle, cup-shaped, highly muscular ………………………… ……………………………………………………….…………….... Icelanonchohaptor (Figure 1B)

5. (6) Ventral bar single; dorsal bar single …………………….. ……………………………………….......... Myzotrema cyclepti

6. (5) Ventral bar single; dorsal bar paired …………… ……………………................ Pseudomurraytrema (Figure 1C)

The following section provides formal descriptions of 7 new species and redescriptions of 11 known species of Pseudomurraytrematidae. Several additional specimens were identified as Anonchohaptor sp. based on general morphology but lacked sufficient diagnostic features for species-level identification; these specimens are included in the phylogenetic analyses pending further taxonomic resolution.

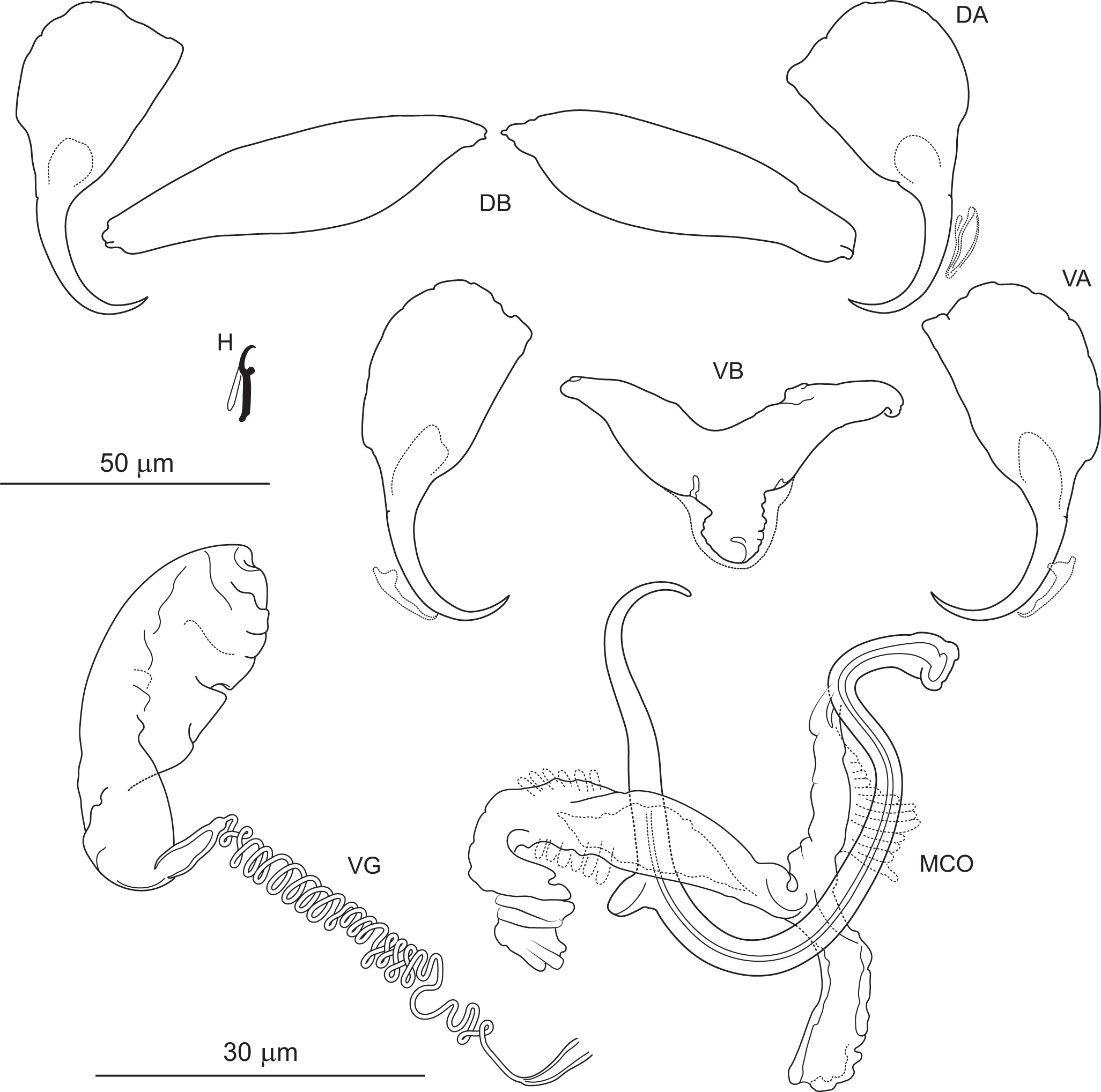

Anonchohaptor meganbeanae n. sp. (Figure 3)

Type host and locality: Ictiobus bubalus (Rafinesque) – Guadalupe River, San Marcos (29°53′24″N, 97°56′03″W), Texas (4 June 2023).

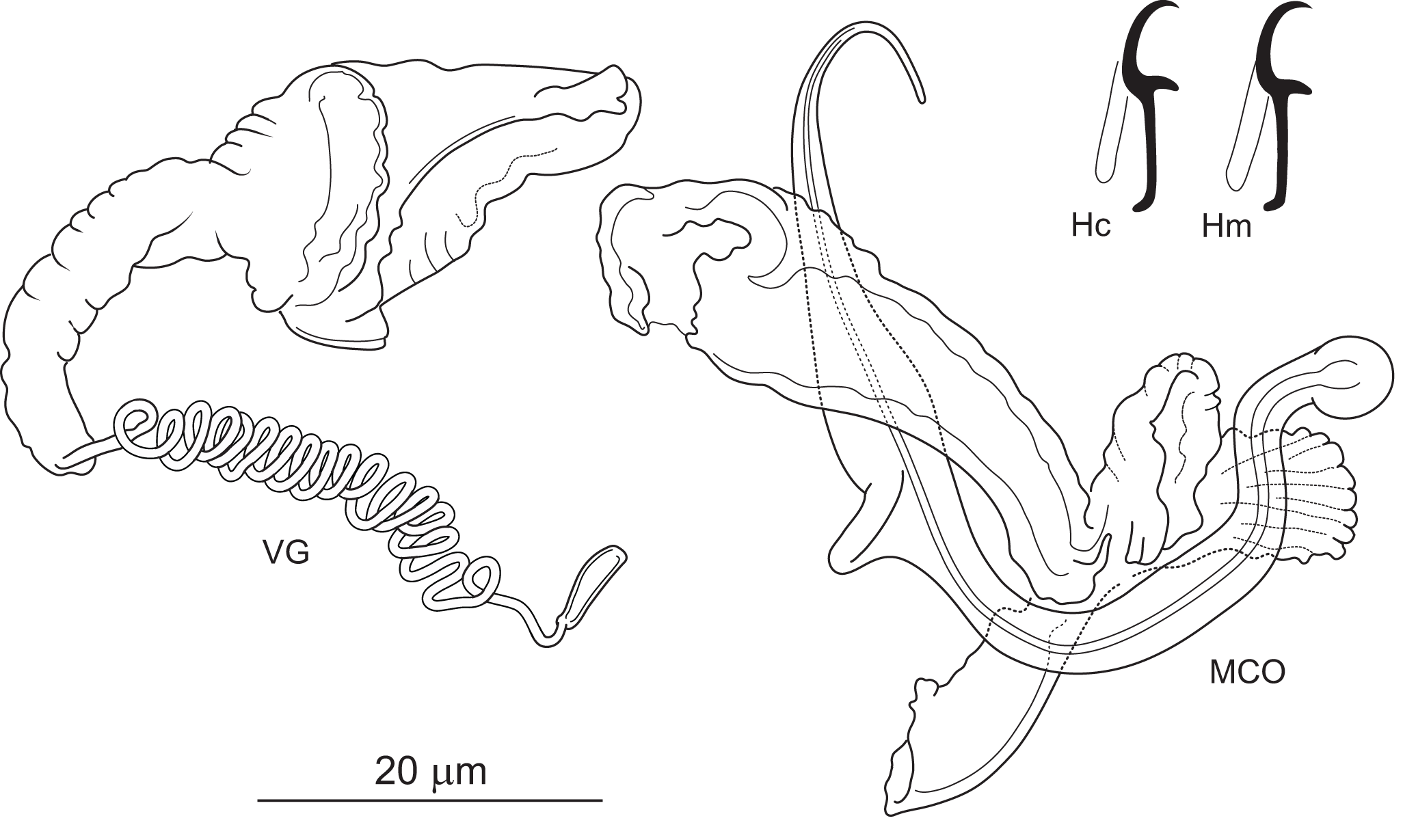

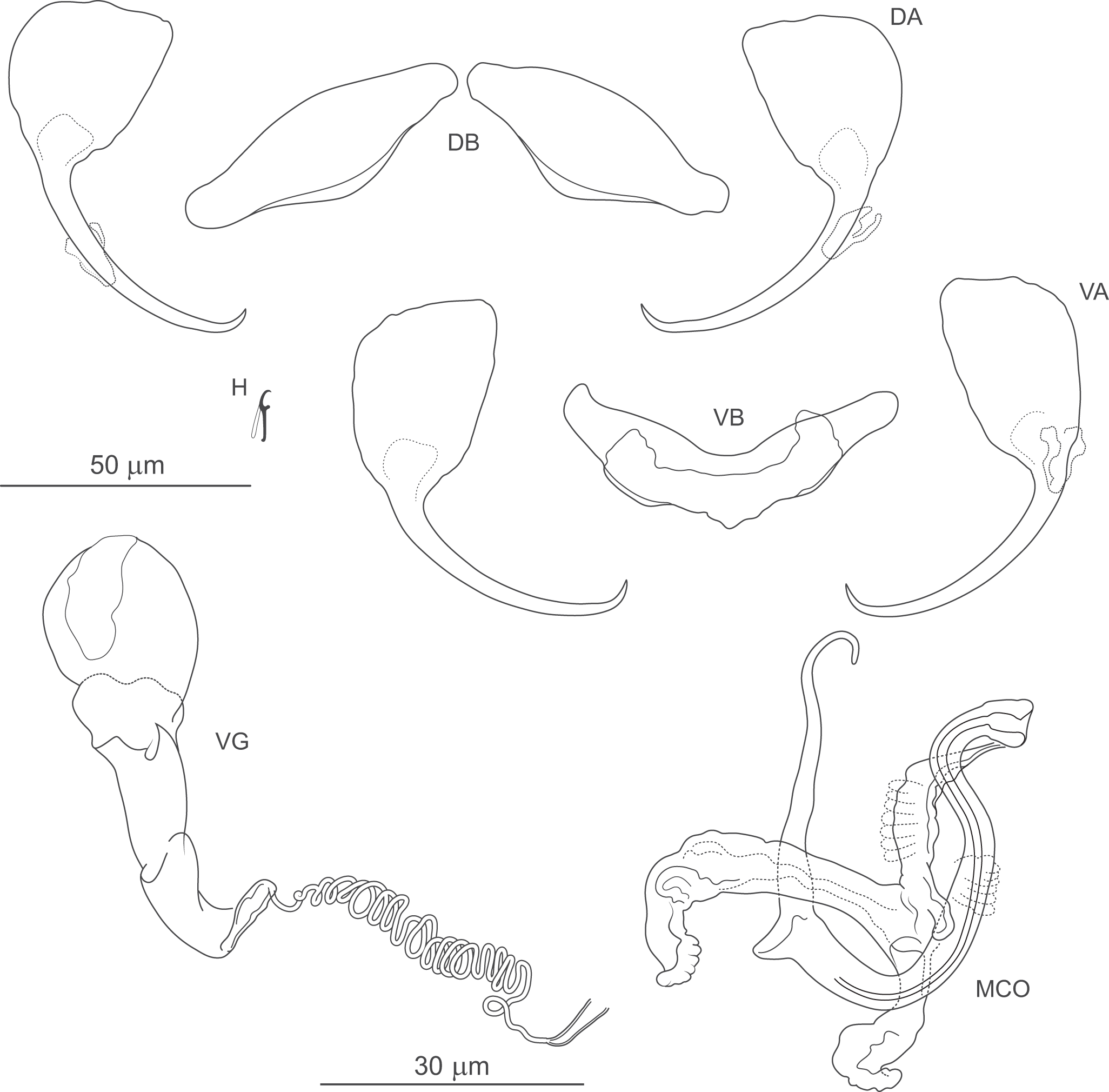

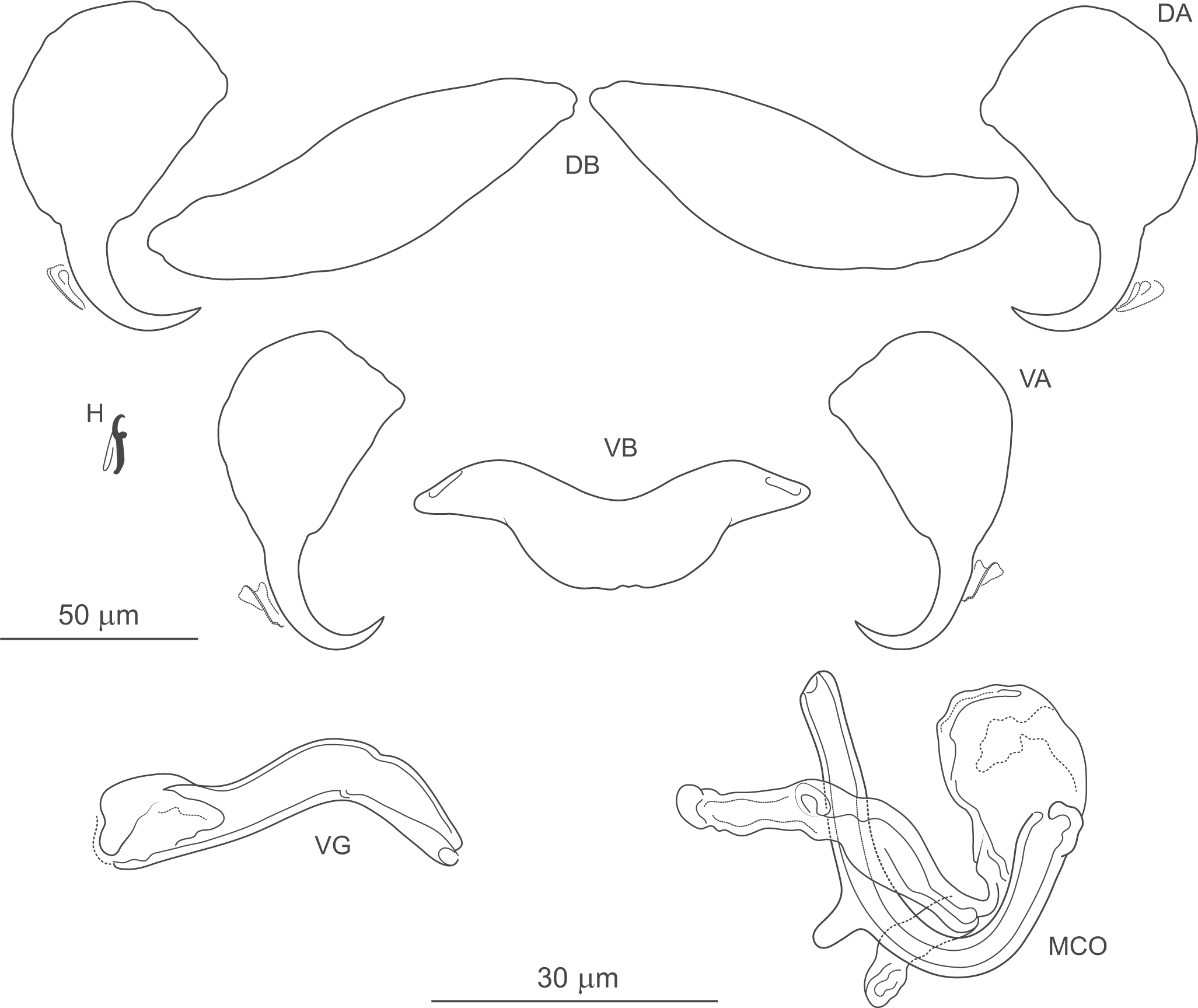

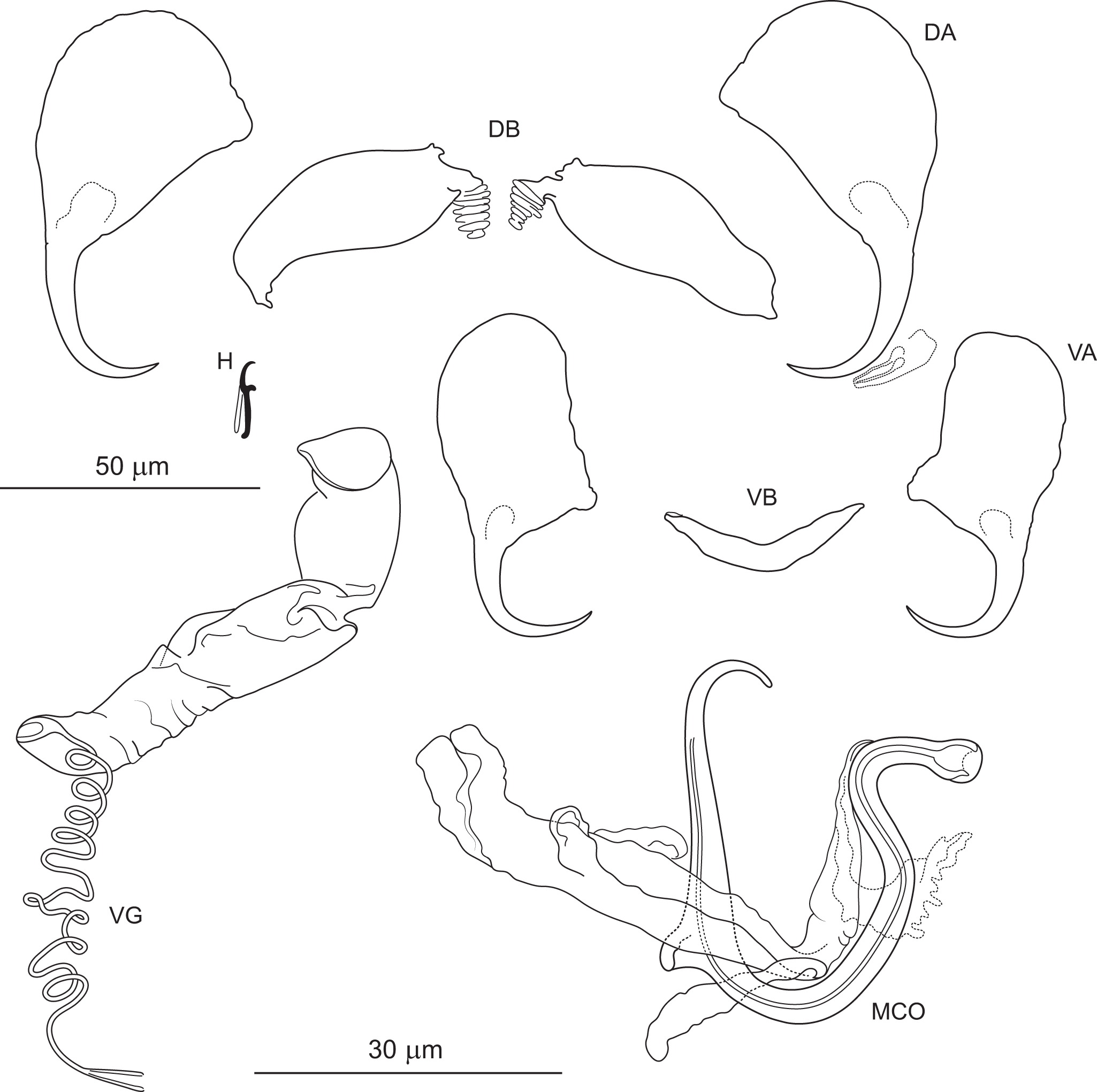

Figure 3. Anonchohaptor meganbeanae n. sp. ex Ictiobus bubalus (Texas): Hc – central hook; Hm – marginal hook; MCO – male copulatory organ; VG – vagina.

Other locality: Mississippi River, Illinois (12 July 2022).

Site of infection: Gills.

Etymology: The species is named in honour of Megan Bean (Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, USA) for her valuable contributions to the research and conservation of North American freshwater fishes, and for her support during fish sampling in Texas in 2023.

ZooBank registration (LSID): urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:169FD241-5A6B-4EA2-8BE5-91576CE8C422.

Prevalence and intensity of infection: Texas – 67% (2 fish infected/3 fish examined); 3 parasites per infected host. Illinois – 25% (1 fish infected/4 fish examined); 4 parasites per infected host (juveniles).

Type and voucher specimens: Holotype (USNM 1762124); 1 paratype (USNM 1762125); 1 hologenophore (USNM 1762126).

Description: Body dorsoventrally flattened, tapering posteriorly, with maximum width in anterior trunk region, just posterior to cephalic lobes. Cephalic region hammer-shaped, well defined, markedly wider than anterior trunk. Peduncle short to absent; haptor clearly delimited, distinctly wider than peduncle. Head organs indistinct. Eyes 4; members of posterior pair farther apart than those of anterior pair. Accessory eye granules absent. Approximately 8–10 large cephalic glands per bilateral group, extending from just posterior to pharynx to level of oesophageal bifurcation. Mouth subterminal, located just anterior to pharynx; pharynx subspherical. Oesophagus elongate, bifurcating into 2 intestinal caeca immediately anterior to MCO; caeca apparently united posteriorly.

Ovary looping around right intestinal caecum. Vagina dextroventral, consisting of lightly sclerotized distal funnel-shaped portion and a multiply coiled proximal tube (approximately 17 coils). Vitellarium absent in region of reproductive organs. Testis postovarian, ovoid, small relative to ovary; vas deferens looping around left intestinal caecum. MCO comprising copulatory tube and articulated accessory piece. Copulatory tube broadly U-shaped, with submedial spine separating proximal S-shaped portion from narrowed distal portion. S-shaped portion with distinct bends; distal portion curved inward terminally, forming a blunt hook-shaped end; submedial spine moderately developed. Accessory piece 3-armed: proximal arm composed of 2 parts situated bilaterally to the proximal region of the copulatory tube – 1 grooved, the other wing-like; medial arm paddle-shaped; distal arm longest, robust and groove-like.

Haptor clearly delimited, disc-shaped, armed with 2 central and 12 marginal hooks; anchor-bar complexes absent. Hooks of similar shape and size; each with an elongate thumb projecting perpendicularly from shaft; shank uniform or slightly tapered proximally, with a rounded and slightly recurved base; filamentous hooklet (FH) loop about three-quarters of shank length.

Measurements: Body length 723 (461–985; n = 2); greatest width 192 (125–258; n = 2). Pharynx 68 (54–81; n = 2) in diameter. Haptor 149 (81–217; n = 2) long, 240 (120–360; n = 2) wide. Central hook 13 (n = 3) long, marginal hook 13 (12–13; n = 3) long. MCO – tube curved length 76 (n = 1).

Remarks: Anonchohaptor currently comprises 3 valid species: A. anomalum Mueller, 1938; A. muelleri Kritsky, Leiby & Shelton, 1972; and A. olseni Leiby, Kritsky & Bauman, 1973 (Mueller Reference Mueller1938; Kritsky et al. Reference Kritsky, Leiby and Shelton1972; Leiby et al. Reference Leiby, Kritsky and Bauman1973). Anonchohaptor meganbeanae n. sp. clearly differs from A. muelleri by having hooks of uniform size (vs central hooks distinctly larger than marginal hooks in A. muelleri). It can be distinguished from A. anomalum by its smaller hooks (13 vs 17 in A. anomalum) and a vagina that appears to be less coiled (17 vs 11 coils in A. anomalum), based on the original illustration (see Figure 4 in Mueller Reference Mueller1938). Compared to A. olseni, the new species has slightly larger hooks (12–13 vs 9–12).

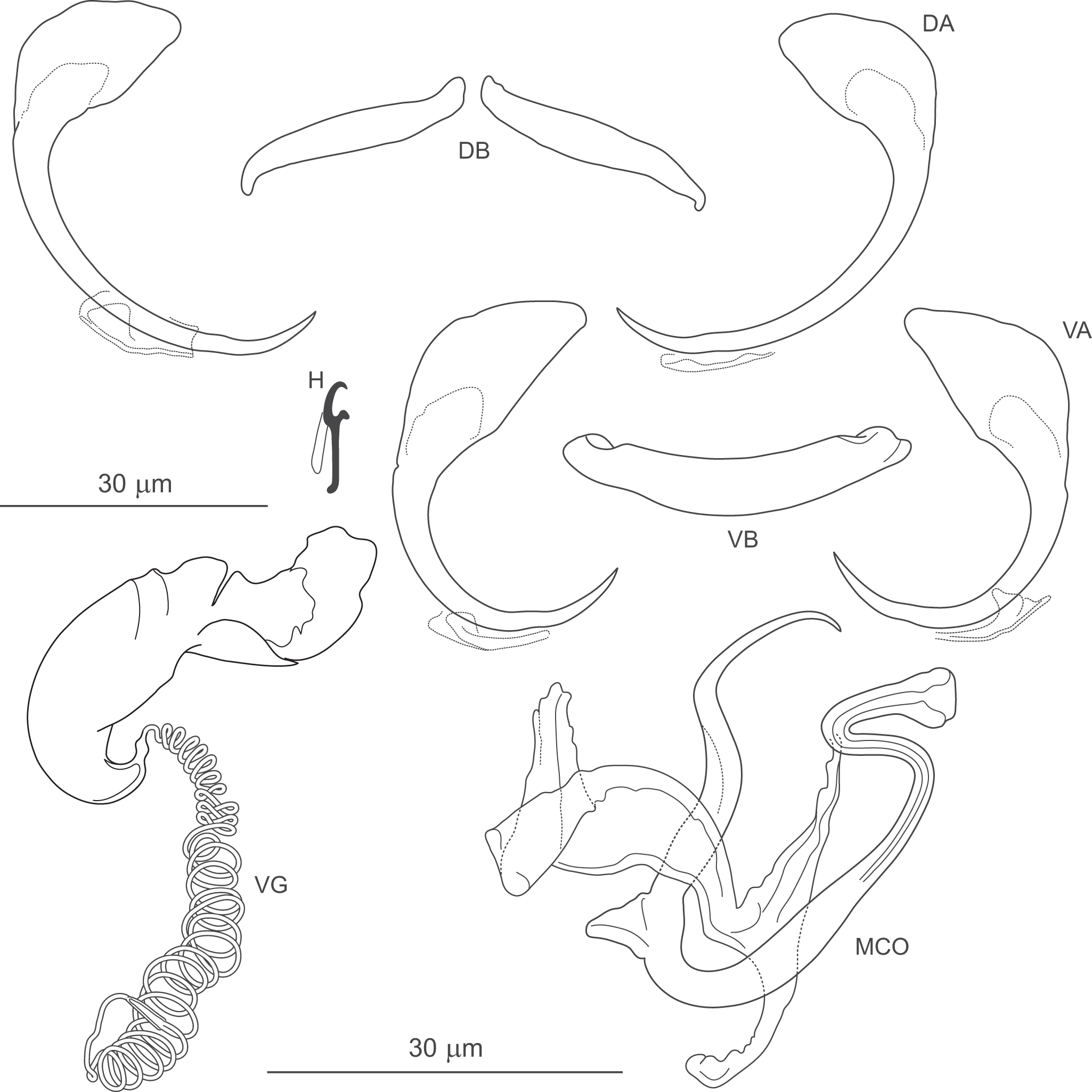

Icelanonchohaptor cherubinus n. sp. (Figure 4)

Type host and locality: Ictiobus bubalus (Rafinesque) – Oxbow south of Cumbest Bridge landing, Pascagoula River (30°30′23″N, 88°32′25″W), Mississippi (19 June 2019).

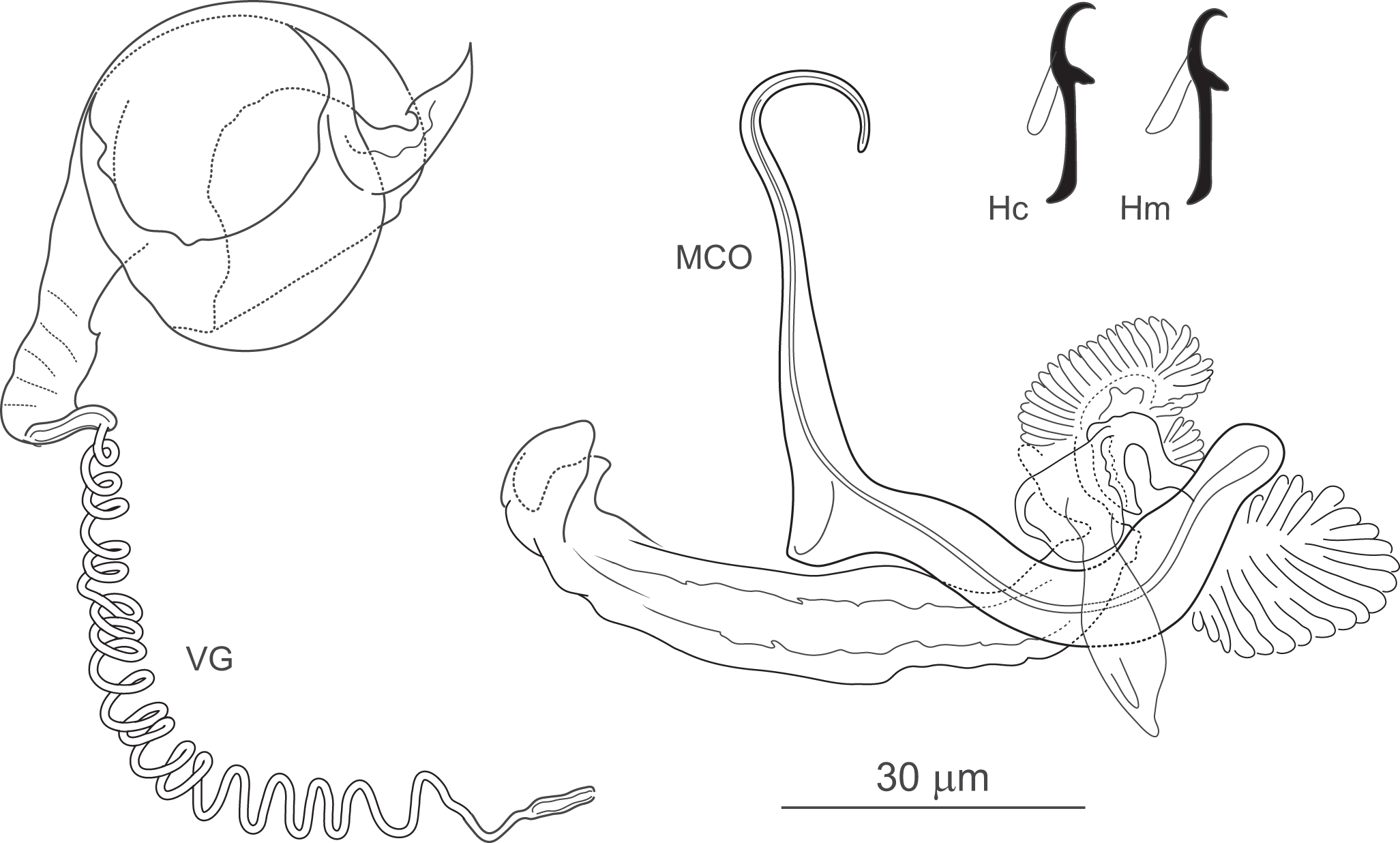

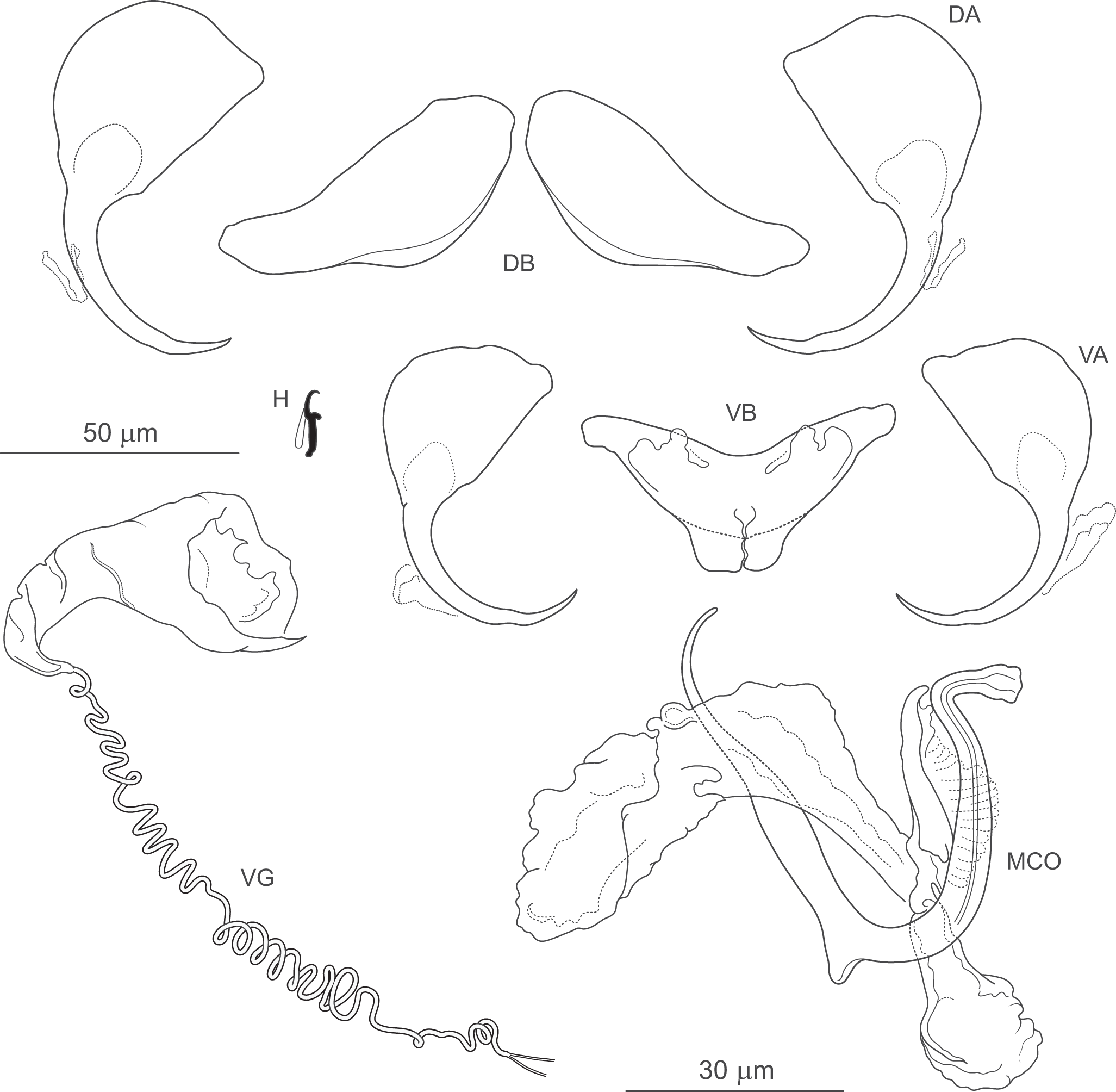

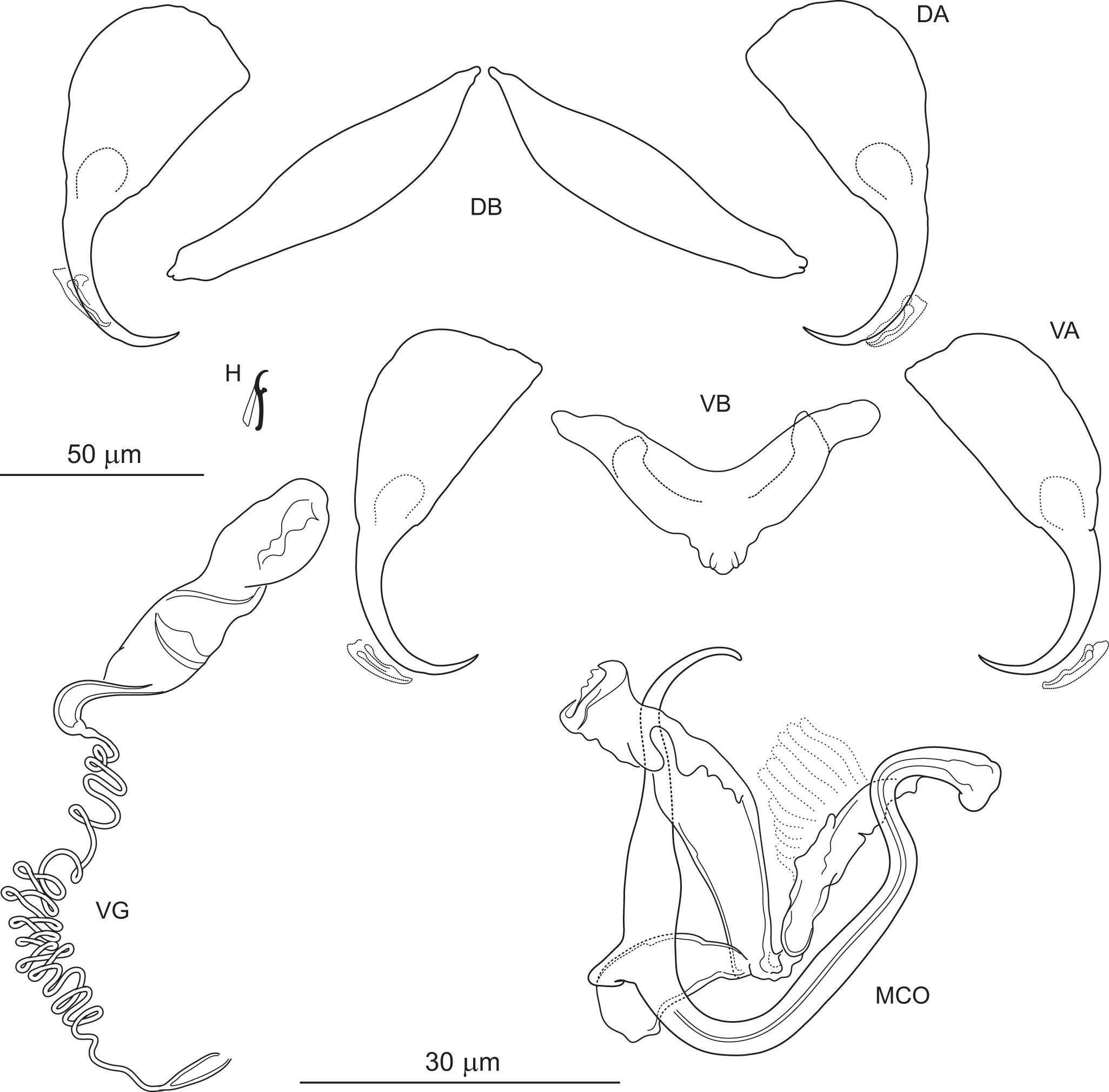

Figure 4. Icelanonchohaptor cherubinus n. Sp. ex Ictiobus bubalus (Mississippi): Hc – central hook; Hm – marginal hook; MCO – male copulatory organ; VG – vagina.

Site of infection: Fins.

Etymology: The specific name cherubinus is derived from kerūv (Hebrew, Latinized), referring to the Cherubim – a class of celestial beings traditionally associated with strength and guardianship. The name refers to wing-like extensions flanking the proximal region of the MCO.

ZooBank registration (LSID): urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:CF1B713C-D437-42C0-8E05-FD2EBDB10A6A.

Prevalence and intensity of infection: 50 % (1 fish infected/2 fish examined); 4 parasites per infected host.

Type and voucher specimens: Holotype (USNM 1762127); 2 paratypes (USNM 1762128, 1762129); 2 hologenophores (USNM 1762130, 1762131).

Description: Body elongate, with nearly uniform width throughout its length, dorsoventrally flattened. Cephalic region trapezoidal to bluntly arrow-shaped. Peduncle merging into haptor; boundary indistinct, peduncle and haptor of equal width. Head organs 4 bilateral pairs. Two large cells, function unknown, present just anterior to eyes. Eyes 4; members of posterior pair farther apart than those of anterior pair. Fine line of pigment granules extending posteriorly from each posterior eye, branching radially at level of posterior part of pharynx. Accessory eye granules absent. Approximately 11 large cephalic glands in each bilateral group, extending from just posterior to pharynx to level of oesophageal bifurcation. Mouth subterminal, just anterior to large pharynx. Pharynx subspherical. Oesophagus elongate, bifurcating into 2 intestinal caeca immediately anterior to MCO; caeca apparently united posteriorly.

Ovary looping right intestinal caecum. Vagina dextroventral, comprising lightly sclerotized distal funnel-shaped portion and multiply coiled proximal tube. Vitellarium absent in region of reproductive organs; 2 vitelline bulbs lateral to oesophagus, narrowing at level of bifurcation, continuing posteriorly as 2 lateral bands along intestinal caeca. Testis postovarian, ovoid, small relative to ovary; vas deferens loops left intestinal caecum. MCO comprising copulatory tube and articulated accessory piece. Copulatory tube broadly U-shaped, with submedial spine separating proximal S-shaped portion from narrowed distal portion. S-shaped portion with shallow and indistinct bends; distal portion curved inward terminally, forming a blunt sickle-shaped end; submedial spine well-developed. Accessory piece 3-armed; proximal arm formed by wing-like, finely striated extensions, situated bilaterally to proximal part of copulatory tube; medial arm elongate, leaf-shaped; distal arm longest, robust, groove-like.

Haptor poorly demarcated from a short peduncle, cup-shaped, armed with 2 central and 12 marginal hooks; anchor-bar complexes absent. Hooks of similar shape and size; each with an elongate thumb projecting obliquely downward from shaft; shank slightly curved and expanded proximally; FH loop about one-half of shank length.

Measurements: Body length 1906 (1250–2980; n = 3); greatest width 225 (320–430; n = 3). Pharynx 135 (126–148; n = 3) in diameter. Haptor 282 (244–320; n = 3) wide. Central hook 19 (n = 4) long, marginal hook 19 (19–20; n = 4) long. MCO – tube curved length 107 (104–111; n = 3).

Remarks: To date, 4 species of Icelanonchohaptor have been described: I. icelanonchohaptor Leiby, Kritsky & Peterson, 1972 from Ictiobus cyprinellus (Missouri River, North and South Dakota), I. microcotyle Kritsky, Leiby & Shelton, 1972 from Carpioides carpio (Missouri River, North and South Dakota), I. fyviei Dechtiar & Dillon, 1974 from Carpiodes cyprinus (Lake Erie, Canada) (Kritsky et al. Reference Kritsky, Leiby and Shelton1972, Leiby et al. Reference Leiby, Kritsky and Peterson1972, Dechtiar and Dillon Reference Dechtiar and Dillon1974) and recently I. tropicalis Mendoza-Franco, Hernández-Gómez & Caspeta-Mandujano, 2023 from Ictiobus meridionalis (Recreo River, Tabasco, Mexico) (Mendoza-Franco et al. Reference Mendoza-Franco, Hernández-Gómez and Caspeta-Mandujano2023).

Icelanonchohaptor cherubinus n. sp. is similar to I. microcotyle and I. seraphinus n. sp. (see below) in possessing a MCO with conspicuous wing-like expansions of the accessory piece situated bilaterally to the proximal part of the copulatory tube. Icelanonchohaptor cherubinus n. sp. differs clearly from both congeners in the morphology of the hooks: the thumb is obliquely truncated (vs beak-shaped in I. microcotyle and I. seraphinus n. sp.), and they are slightly longer (19–20 vs 16–19 and 16–17 in I. microcotyle and I. seraphinus n. sp., respectively). In addition, I. cherubinus n. sp. differs from I. microcotyle in having a vagina with a longer vaginal tube comprising approximately 18 coils (vs 10 coils in I. microcotyle).

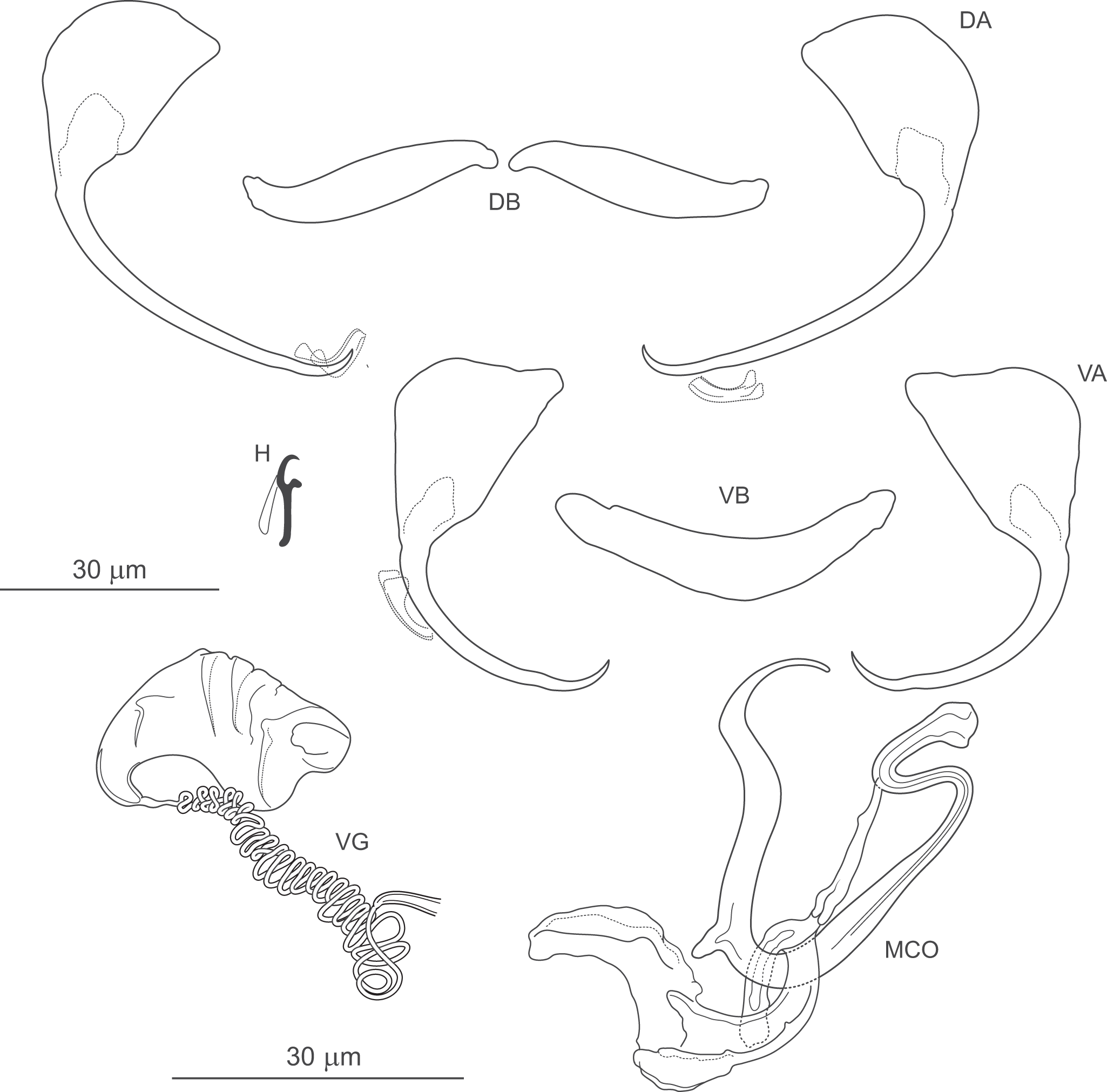

Icelanonchohaptor seraphinus n. sp. (Figure 5)

Type host and locality: Ictiobus niger (Rafinesque) – Hutson Lake, Pascagoula River (30°52′21″N, 88°45′47″W), Mississippi (17 June 2019).

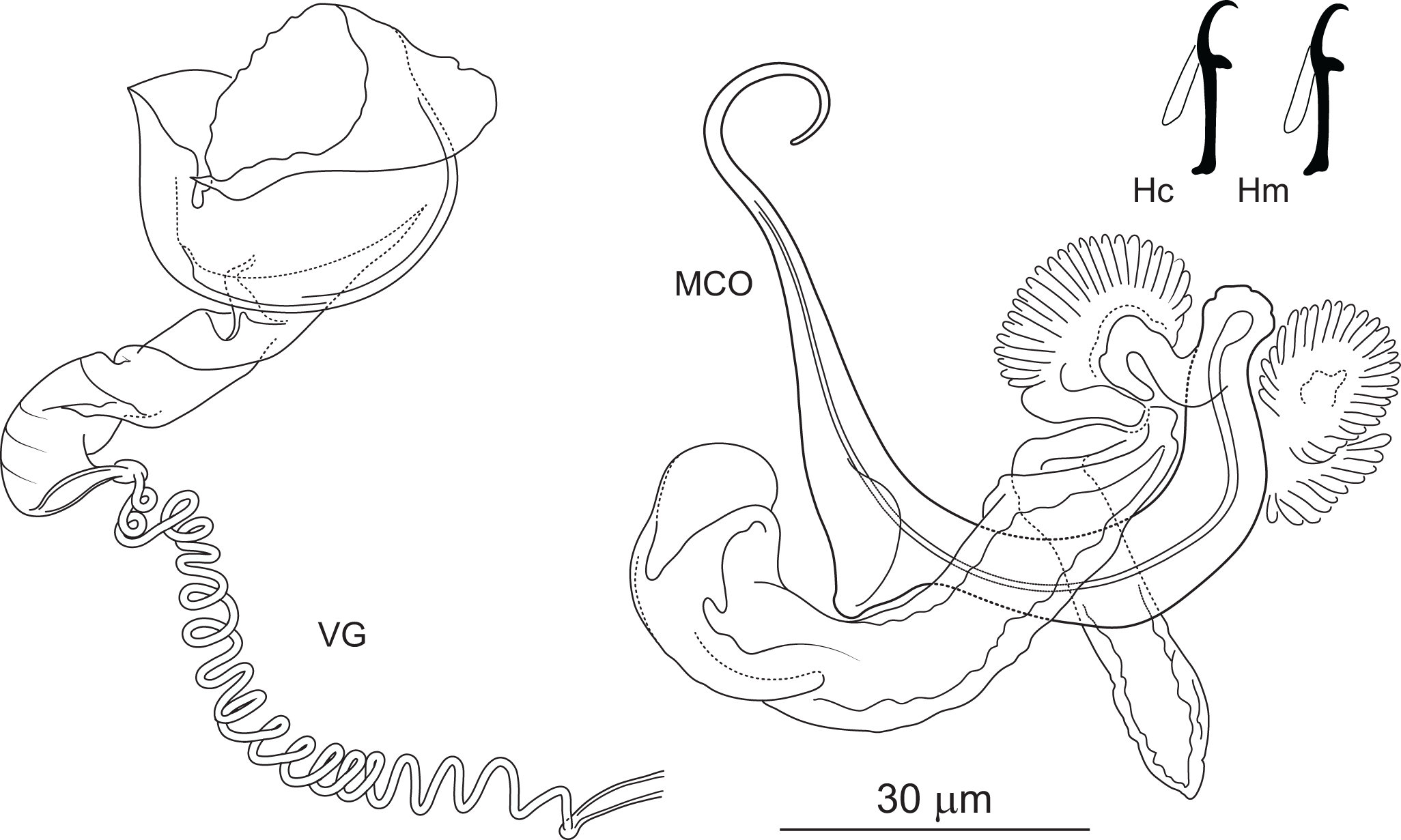

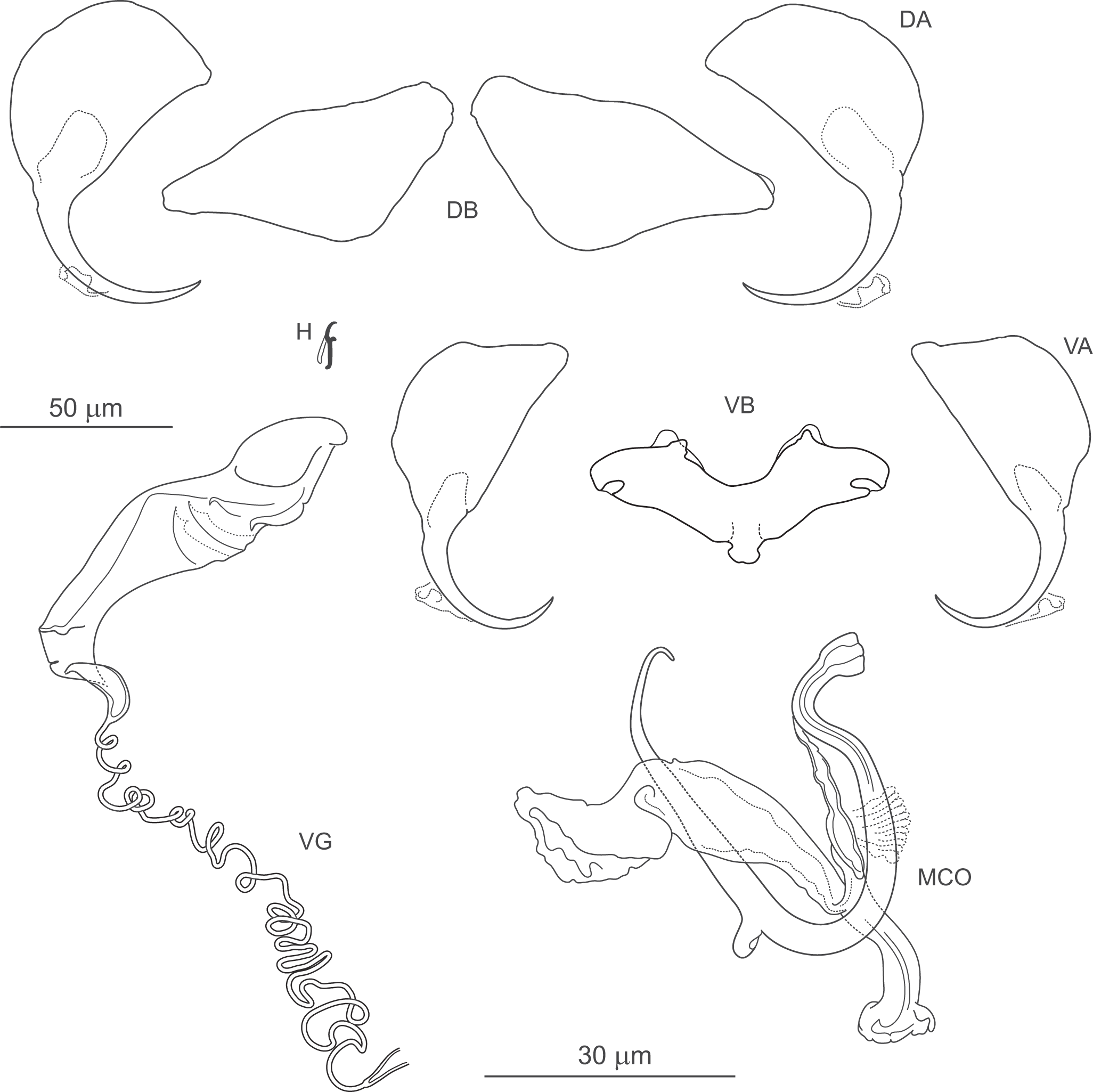

Figure 5. Icelanonchohaptor seraphinus n. sp. ex Ictiobus Niger (Mississippi): Hc – central hook; Hm – marginal hook; MCO – male copulatory organ; VG – vagina.

Site of infection: Fins.

Etymology: The specific name seraphinus is derived from śərāfîm (Hebrew, Latinized), referring to the Seraphim – a class of high-ranking angels traditionally associated with wings. The name alludes to wing-like extensions flanking the proximal region of the copulatory tube.

ZooBank registration (LSID): urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:4EEEF393-E855-41C3-9BDA-1DAF7A93C294.

Prevalence and intensity of infection: 67% (2 fish infected/3 fish examined); 3 parasites per infected host (mostly juveniles).

Type and voucher specimens: Holotype (USNM 1762132); 1 hologenophore (USNM 1762133).

Description: Due to limited material, internal anatomy could not be described. Four of 5 specimens were juveniles; the only adult (hologenophore) was incomplete, with part of the body processed for DNA extraction. Description is based on morphometry of sclerotized structures, illustrated by line drawings. MCO comprising copulatory tube and articulated accessory piece. Copulatory tube broadly U-shaped, with submedial spine separating proximal S-shaped portion from narrowed distal portion. S-shaped portion with shallow and indistinct bends; distal portion curved inward terminally, forming a blunt sickle-shaped end; submedial spine massive.

Haptor poorly demarcated from a short peduncle, cup-shaped; armed with 2 central and 12 marginal hooks; anchor-bar complexes absent. Hooks of similar shape and size; each with beak-like thumb projecting perpendicularly from shaft; shank slightly expanded proximally; FH loop about one-half of shank length.

Measurements: Central hook 17 (n = 1) long, marginal hook 17 (16–17; n = 1) long. MCO – tube curved length 119 (117–119; n = 3).

Remarks: Icelanonchohaptor seraphinus n. sp. is recovered as sister species to I. cherubinus n. sp. in our phylogenetic analyses (see Figures 23 and 24). Icelanonchohaptor seraphinus n. sp. differs from the latter species in the shape and size of the hooks (see Remarks for I. cherubinus n. sp.) and in having an MCO that appears more robust. Icelanonchohaptor seraphinus n. sp. also resembles I. microcotyle in the general shape of the MCO and hooks, both bearing hooks with a beak-like thumb. It differs from I. microcotyle by possessing a vagina with a longer vaginal tube comprising approximately 18 coils (vs 10 coils in I. microcotyle).

Pseudomurraytrema species parasitizing species of Catostomus (Catostomini)

Pseudomurraytrema ardens n. sp. (Figure 6)

Type host and locality: Catostomus macrocheilus Girard – Siuslaw River, Oregon (27 June 2024).

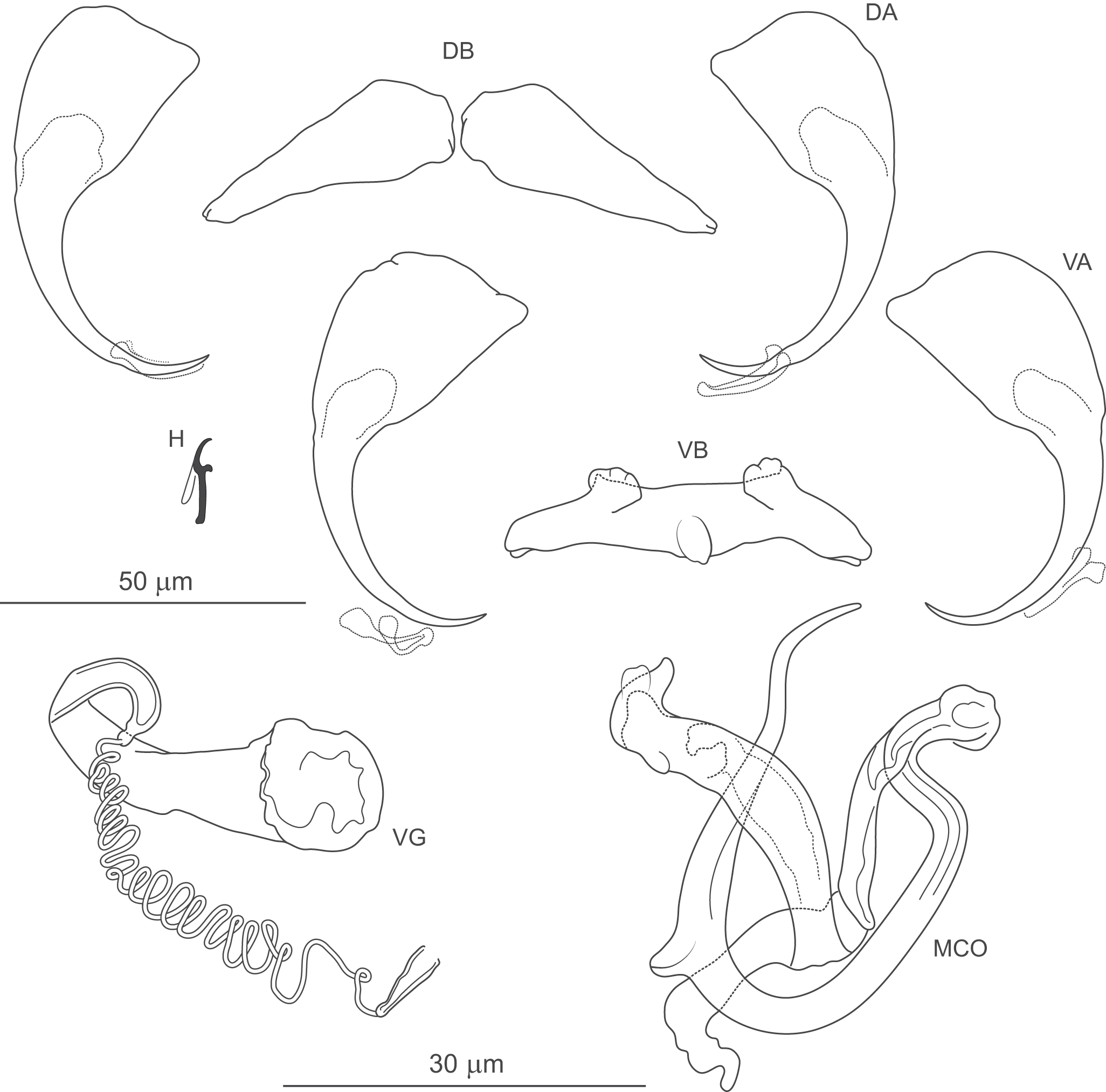

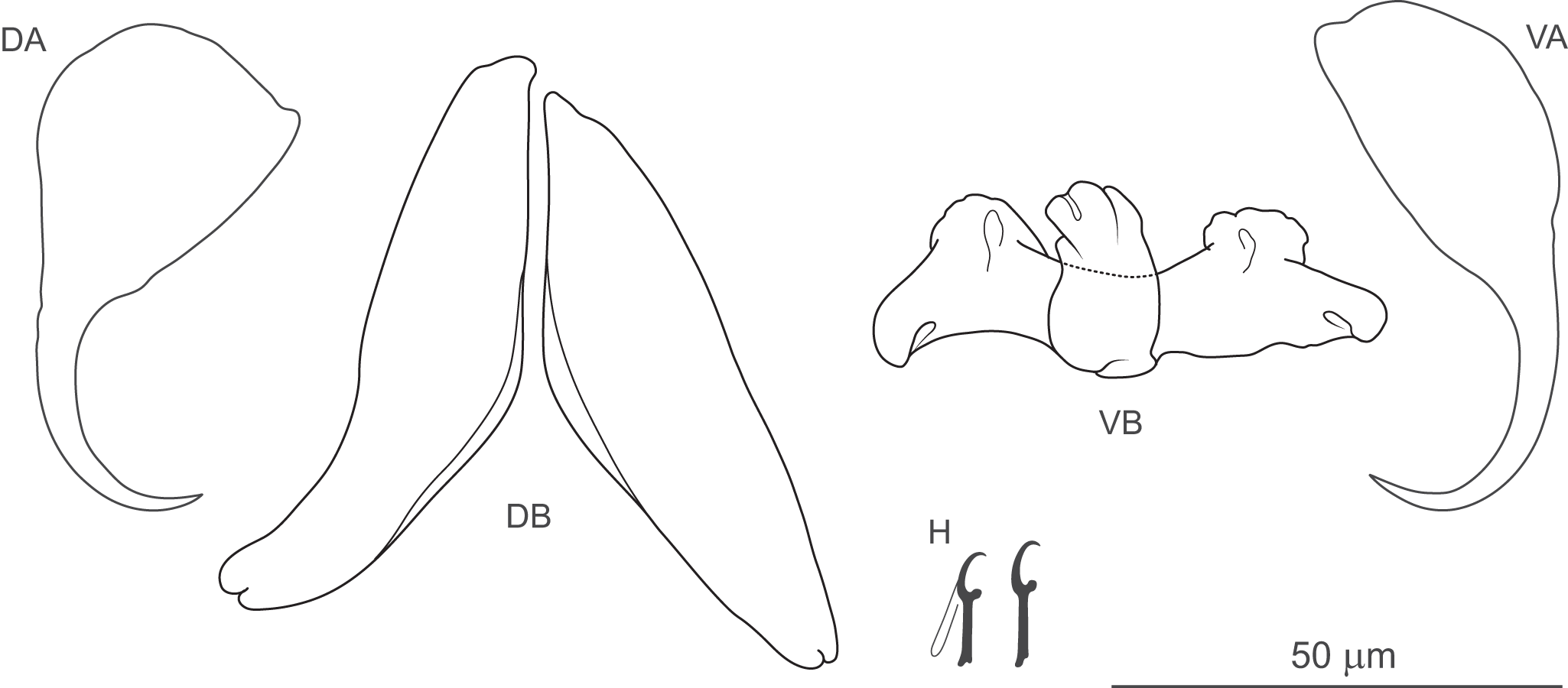

Figure 6. Pseudomurraytrema ardens n. sp. ex Catostomus macrocheilus (Oregon): VA – ventral anchor, VB – ventral bar; DA – dorsal anchor; DB – dorsal bar; H – hook; MCO – male copulatory organ; VG – vagina.

Previous records: Catostomus ardens Jordan & Gilbert – Snake River, Idaho (as Pseudomurraytrema sp. ‘ardens’; Littlewood et al. Reference Littlewood, Rohde and Clough1998).

Site of infection: Gills.

Etymology: The specific name ardens is after the host on which the species was first found.

ZooBank registration (LSID): urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:6EC27A7D-15FB-4B73-A7D2-2CBB1A6754F1.

Prevalence and intensity of infection: 50% (4 fish infected/8 fish examined); 2–5 parasites per infected host (mostly juveniles).

Type and voucher specimens: Holotype (USNM 1762081); 1 paratype (USNM 1762082); 3 hologenophores (USNM 1762083, 1762084, 1762085).

Description: Body elongate to fusiform, dorsoventrally flattened. Cephalic region relatively wide; trunk width uniform; peduncle short or absent. Haptor subhexagonal in dorsoventral view, wider than long, medium to large relative to trunk size. Head organs poorly defined. Two pairs of eyespots with poorly associated chromatic granules; members of both pairs similar in size and spacing. Accessory chromatic granules sparse, scattered in cephalic and anterior trunk region. Ventral mouth located between anterior eyespots. Pharynx subovate to spherical; oesophagus and intestinal caeca indistinct.

Gonads tandem or with testis slightly overlapping ovary dorsally. Ovary looping dorsoventrally around right intestinal caecum. Ootype and uterus not observed. Vagina dextroventral, located at about half of body length, composed of trumpet-shaped distal part and multiple-coiled vaginal tube with proximal fork. Vaginal canal and seminal receptacle not observed. Vitellarium follicular, extending from level of oesophagus to near haptor; absent in region of other reproductive organs. Transverse vitelline ducts not observed. Testis postovarian. Vas deferens and seminal vesicle not observed. Two prostatic reservoirs unequal in size. MCO composed of articulated copulatory tube and accessory piece. Copulatory tube U-shaped, with sharply S-shaped proximal portion (2 distinct bends in proximal third), separated by submedial spine from narrowed, curved distal part. Accessory piece with 3 rami: proximal ramus articulated to base; distal ramus largest, forming V-shaped structure with proximal 1; medial ramus arising externally to their junction.

Haptor armed with dorsal and ventral anchor–bar complexes and 7 pairs of hooks. Ventral and dorsal anchors similar in shape and size; each with narrow, terminally flattened base, elongate curved shaft and short point. Distal shaft undulation more evident in dorsal anchor. Ventral bar saddle-shaped, with 2 submedial protuberances on anterior margin and posteromedial knob-like process; ends slightly recurved posteriorly. Paired dorsal bar subtriangular, with broad, angularly rounded medial end tapering smoothly to pointed lateral ends. Hooks similar in shape and size; each with hooked thumb projecting perpendicularly from shank; shank uniform or slightly tapered proximally; base slightly enlarged, flattened; FH loop about three-quarters of shank length.

Measurements: Body 786 (n = 1) long; greatest width 174 (n = 1). Pharynx 69 (n = 1) long, 63 (n = 1) wide. Haptor 96 (n = 1) long, 209 (n = 1) wide. Ventral anchor 57 (54–60; n = 4) long; base width 21 (19–23; n = 4). Dorsal anchor 57 (55–59; n = 4) long; base width 21 (19–22; n = 4).Ventral bar 56 (53–59; n = 2) long. Paired dorsal bar 40 (37–43; n = 2) long. Hooks 14 (13–15; n = 4) long. MCO – tube curved length 87 (84–92 n = 3); tube height 34 (31–37; n = 3).

Remarks: This species was first reported by Littlewood et al. (Reference Littlewood, Rohde and Clough1998) as Pseudomurraytrema ardens, based on specimens collected by Delane Kritsky from Catostomus ardens in Idaho. Although Littlewood et al. (Reference Littlewood, Rohde and Clough1998) included genetic sequences of this species in their phylogenetic analysis, they did not formally describe it. Consequently, Boeger et al. (Reference Boeger, Kritsky, Domingues and Bueno-Silva2014) considered P. ardens a nomen nudum. Since then, Pseudomurraytrema sp. ‘ardens’ has been used in several other phylogenetic analyses as the only representative of Pseudomurraytrematidae with sequences deposited in GenBank (Olson and Littlewood Reference Olson and Littlewood2002; Bentz et al. Reference Bentz, Combes, Euzet, Riutord and Verneau2003; Šimková et al. Reference Šimková, Plaisance, Matějusová, Morand and Verneau2003; Plaisance et al. Reference Plaisance, Littlewood, Olson and Morand2005; Boeger et al. Reference Boeger, Kritsky, Domingues and Bueno-Silva2014; Ogawa and Itoh Reference Ogawa and Itoh2017; Moreira et al. Reference Moreira, Luque and Šimková2019; Soares et al. Reference Soares, Domingues and Adriano2021). This species is formally described here based on 3 specimens recovered from Catostomus macrocheilus in Oregon, whose DNA sequences match those of Pseudomurraytrema sp. ‘ardens’ in BLAST analyses. Pseudomurraytrema ardens n. sp. exhibits morphological similarities with P. commersoni n. sp. and P. kritsdelani n. sp., particularly in having a trumpet-shaped distal portion of the vagina and a copulatory tube with an undulating distal section that typically curves outward at the tip. Among these, P. ardens n. sp. most closely resembles P. kritsdelani n. sp. (see below) in the morphology of the ventral anchors and the vagina. In both species, the ventral anchors possess a moderately broad base with a flattened proximal margin and an elongate, curved shaft exhibiting slight undulation near its junction with a short point. The vaginas of both species consist of a trumpet-shaped distal portion and a multiply coiled vaginal tube. Pseudomurraytrema ardens n. sp. clearly differs from P. kritsdelani n. sp. by having: (1) morphologically similar ventral and dorsal anchors (vs a dorsal anchor with a significantly wider fan-shaped base compared to the ventral anchor in P. kritsdelani n. sp.), (2) ventral and dorsal anchors with a smooth outer margin between shaft and base (vs an abrupt junction between shaft and base, especially evident in the dorsal anchors of P. kritsdelani n. sp.), (3) a hook with a narrower shank of nearly uniform diameter (vs thicker and slightly inflated shank on its inner side, except for the curved terminal part, in P. kritsdelani n. sp.; see Figure 7 for comparison) and (4) narrower paired dorsal bar with a less bulgy medial end. In addition, P. ardens n. sp. ranks among the smallest representatives of Pseudomurraytrema, differing in body size from P. kritsdelani n. sp. (786 vs 1040 in P. kritsdelani n. sp.).

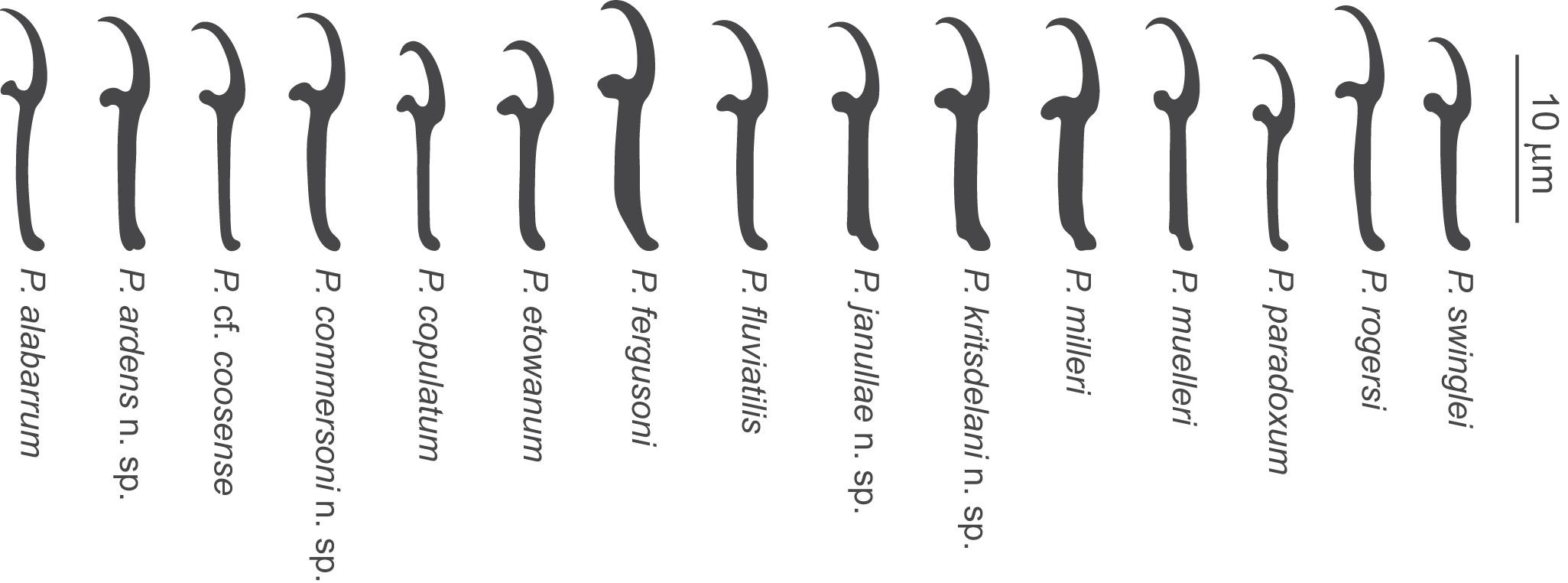

Figure 7. Comparative morphology of hooks of Pseudomurraytrema species: all 11 previously described Nearctic species and 4 new species. Pseudomurraytrema coosense tentatively identified (cf.); P. Muelleri illustrated from the holotype, not among present material.

Pseudomurraytrema commersoni n. sp. (Figure 8)

Synonym: Murraytrema copulatum Mueller, Reference Mueller1938 (in part).

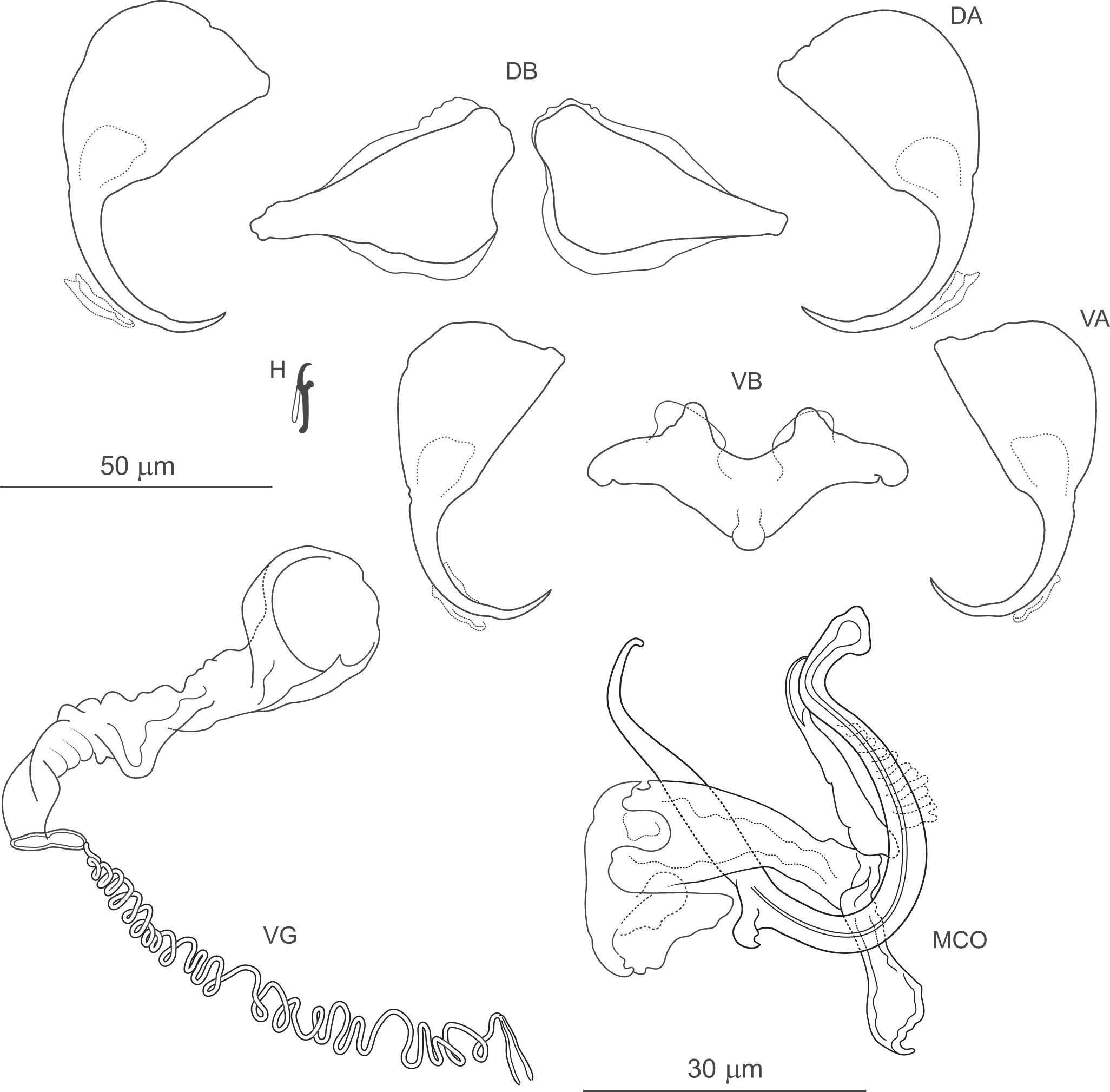

Figure 8. Pseudomurraytrema commersoni n. sp. ex Catostomus commersonii (Wisconsin): VA – ventral anchor, VB – ventral bar; DA – dorsal anchor; DB – dorsal bar; H – hook; MCO – male copulatory organ; VG – vagina.

Type host and locality: Catostomus commersonii (Lacepède) – Hickory Oak Pond, Wisconsin (23 September 2018).

Other records: Catostomus commersonii – Moore’s Creek (43°54′15″N, 91°13′31″W), Wisconsin (9 July 2022).

Previous records: Catostomus commersonii – Chautauqua Lake and French Creek, near Panama, New York (as Murraytrema copulatum; Mueller Reference Mueller1938).

Unconfirmed host and locality records: Catostomus commersonii and Moxostoma pisolabrum Trautman & Martin (syn. M. aureolum) – Silver Creek (Fond du Lac Co.), St. Croix River (Burnett Co.), Wisconsin (Mizelle and Klucka Reference Mizelle and Klucka1953).

Site of infection: Gills.

Etymology: The specific name commersoni is, like the host, in honour of the French naturalist Philibert Commerson.

ZooBank registration (LSID): urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:62CD8EFD-97F3-4496-8776-57E0C721C5A7.

Prevalence and intensity of infection: Wisconsin (2018) – 8% (1 fish infected/13 fish examined); 2 parasites per infected host. Wisconsin (2022) – 25% (2 fish infected/8 fish examined); 1–2 parasites per infected host.

Type and voucher specimens: Holotype (USNM 1762087); 1 hologenophore (USNM 1762088).

Description (based on 1 whole-mounted specimen and 1 hologenophore; both specimens were incomplete and did not allow assessment of body morphology or internal anatomy). MCO composed of articulated copulatory tube and accessory piece. Copulatory tube U-shaped, with thick, loosely S-shaped proximal portion (2 shallow, equally spaced bends), separated by submedial spine from narrowed distal part, usually curved outwards at tip. Accessory piece with 3 rami: proximal ramus articulated to base, bearing finger-like processes; distal ramus largest, forming V-shaped structure with proximal one; medial ramus massive, with frilled margin. Vagina dextroventral, with trumpet-shaped distal part and short vaginal tube with approximately 5 coils.

Haptor armed with dorsal and ventral anchor–bar complexes and 7 pairs of hooks. Ventral and dorsal anchors similar in shape and size; each with markedly broad, fan-shaped base, slightly bent shaft well delimited from short recurved point. Ventral bar saddle-shaped, with 2 submedial protuberances along anterior margin and posteromedial expansion; ends recurved posteriorly. Paired dorsal bar robust, with convex posterior margin (maximum convexity just beyond mid-length) and narrowed lateral ends. Hooks similar in shape and size; each with slightly erect, hooked thumb; shank slightly tapered and proximally curved; FH loop about three-quarters of shank length.

Measurements: Ventral anchor 59 (n = 1) long; base width 27 (n = 1). Dorsal anchor 62 (n = 1) long; base width 33 (n = 1). Ventral bar 59 (n = 1) long. Paired dorsal bar 51 (n = 1) long. Hooks 15 (14–15; n = 1) long. MCO – tube curved length 80 (80–81; n = 2); tube height 37 (35–39; n = 2).

Remarks: Mueller (Reference Mueller1938) described Pseudomurraytrema copulatum from the gills of C. commersonii, Hypentelium nigricans, Moxostoma anisurum and Moxostoma erythrurum, but noted that specimens collected from the former host exhibited morphological differences compared to those from the other 3 fish species. He further suggested that these specimens could represent 2 distinct species. Price (Reference Price1967) described Pseudomurraytrema muelleri from C. commersonii in Georgia and stated that his specimens matched those originally described by Mueller (Reference Mueller1938) from the same host. Subsequently, Rogers (Reference Rogers1969) considered P. muelleri to be morphologically identical to Pseudomurraytrema alabarrum, previously described from Minytrema melanops (Rogers Reference Rogers1966), and later that year, Chien (Reference Chien1969) proposed that P. muelleri should be regarded as a synonym of P. alabarrum. Finally, Kritsky and Leiby (Reference Kritsky and Leiby1973) indicated that the specimens identified as P. copulatum from C. commersonii in Wisconsin by Mizelle and Klucka (Reference Mizelle and Klucka1953) likely represent P. alabarrum, and therefore the earlier records of P. copulatum on C. commersonii from New York (Mueller Reference Mueller1938) and Wisconsin (Mizelle and Klucka Reference Mizelle and Klucka1953) should be reassigned to P. alabarrum.

Illustrations by Mueller (Reference Mueller1938; Figures 9, 12 and 13) clearly show that the specimens he identified as P. copulatum from C. commersonii are conspecific with those examined in the present study from the same host species. The morphology of the ventral and dorsal anchor–bar complexes depicted by Mueller (Reference Mueller1938) closely corresponds to that of the present material. Likewise, the MCOs are of highly similar appearance, and the vaginas are clearly distinct from those of all other known Pseudomurraytrema species due to their significantly shorter vaginal tubes. Taken together, this evidence suggests that neither Mueller’s specimens nor those examined herein belong to any of the 3 previously described species (P. alabarrum, P. copulatum, P. muelleri), but instead represent a distinct species, which is described here as P. commersoni n. sp. The most important characters distinguishing P. commersoni n. sp. from the 3 aforementioned species (P. alabarrum, P. copulatum and P. muelleri) are as follows: (1) dorsal and ventral anchors with a broad, fan-shaped base (vs both anchors with comparatively narrower bases in P. alabarrum, P. copulatum and P. muelleri); (2) a robust paired dorsal bar with a markedly widened posterior margin and a medial end distinctly broader than the lateral one (vs paired dorsal bar elongated, slightly widened medially, with both ends similarly narrowed in P. alabarrum, P. copulatum and P. muelleri); (3) a saddle-shaped ventral bar with 2 closely positioned anteromedial protuberances (vs rod-shaped in P. copulatum; saddle-shaped with more widely spaced anteromedial protuberances in P. alabarrum and P. muelleri); (4) a copulatory tube with a thicker, loosely S-shaped proximal portion and a wavy distal portion with the tip usually recurved outwards (vs proximal portion sharply S-shaped and thinner in diameter; distal portion angularly recurved inwards in P. alabarrum, P. copulatum and P. muelleri); and (5) a markedly shorter, and only slightly coiled, vaginal tube (vs long and multiply coiled vaginal tube in all 3 species).

As noted above, although Mueller (Reference Mueller1938) pointed out the differences between monopisthocotylans from C. commersonii and H. nigricans (= type host species for P. copulatum), Mizelle and Klucka (Reference Mizelle and Klucka1953) continued to identify their specimens from C. commersonii and M. pisolabrum (syn. M. aureolum) as P. copulatum. Unfortunately, their illustrations are insufficient for reliable species identification, as figures of the haptoral bars and vagina are lacking, and no voucher specimens were deposited. Although comparison of their drawings of the anchors (Figures 21 and 22) with those of the present material suggests that they were probably dealing with P. commersoni n. sp., the authors did not specify the host species from which the illustrated specimens were obtained. Therefore, the occurrence of P. commersoni n. sp. on M. pisolabrum remains unconfirmed. Apart from its shorter vaginal tube, P. commersoni n. sp. can be readily distinguished from the 3 other congeneric species parasitizing Catostomus species, namely P. ardens n. sp., Pseudomurraytrema kritsdelani n. sp. and P. muelleri, by having ventral and dorsal anchors that are morphologically almost identical, each characterized by a broad, fan-shaped base and a relatively straight shaft clearly delimited from the short point. In contrast, P. kritsdelani n. sp. and P. muelleri possess morphologically dissimilar anchors, whereas P. ardens n. sp. exhibits morphologically similar anchors that are narrower, with a terminally flattened base.

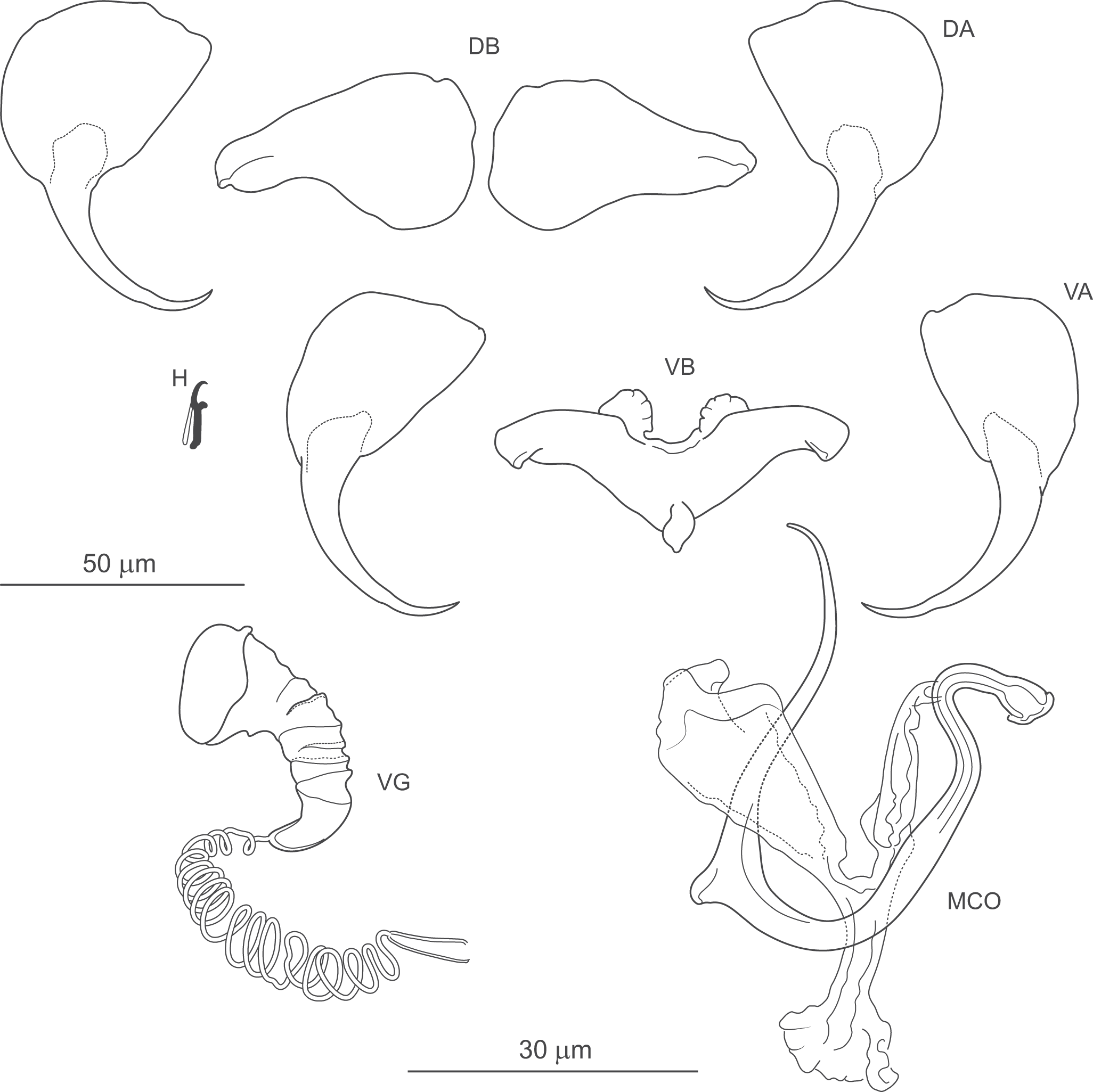

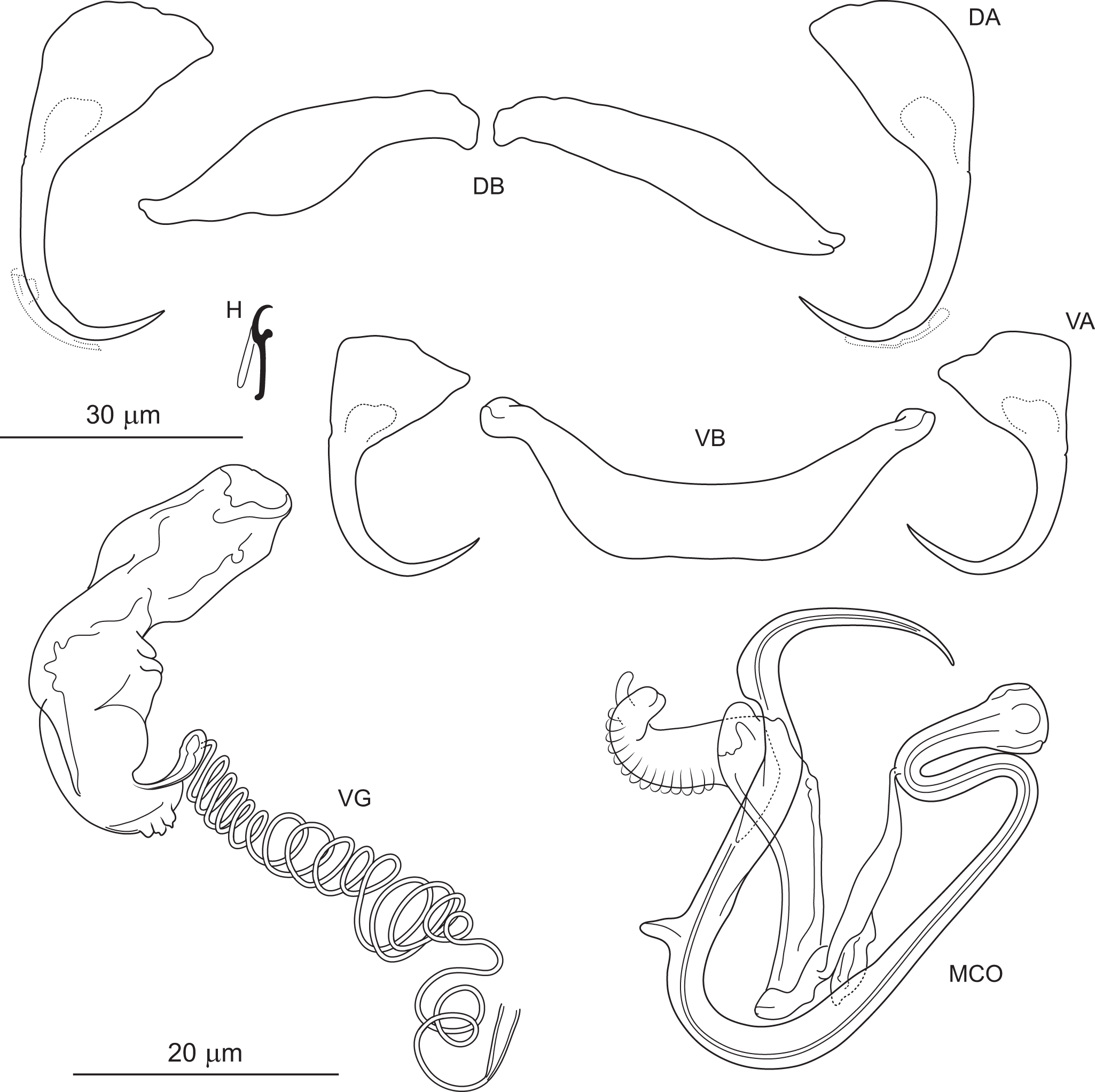

Pseudomurraytrema kritsdelani n. sp. (Figure 9)

Type host and locality: Catostomus ardens – Riverton Road, Blackfoot River (43°09ʹ00ʹʹN, 112˚27ʹ04ʹʹW), Idaho (1 January 1989).

Figure 9. Pseudomurraytrema kritsdelani n. sp. ex Catostomus ardens (Idaho): VA – ventral anchor, VB – ventral bar; DA – dorsal anchor; DB – dorsal bar; H – hook; MCO – male copulatory organ; VG – vagina.

Site of infection: Gills.

Etymology: This species is named for Delane C. Kritsky in recognition of his enormous contributions to the taxonomy and systematics of monopisthocotylans, and for the support he provided for this study.

ZooBank registration (LSID): urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:33A4C552-A3DF-45FB-8A83-A7001AA69932.

Prevalence and intensity of infection: Not available.

Type specimens: Holotype (USNM 1762103); 5 paratypes (USNM 1762104–1762108).

Description: Body elongate to fusiform, dorsoventrally flattened. Cephalic region slightly narrower than trunk, with poorly differentiated cephalic lobes. Trunk widest at or slightly posterior to level of testis. Peduncle short. Haptor subhexagonal in dorsoventral view, wider than long, small relative to trunk size. Head organs not observed. Two pairs of eyespots with poorly associated chromatic granules; members of posterior pair slightly farther apart than those of anterior pair. Accessory chromatic granules sparse, scattered in cephalic and anterior trunk region. Ventral mouth located between anterior eyespots. Pharynx subovate to spherical. Oesophagus short. Intestinal caeca confluent posterior to gonads.

Gonads tandem or with testis partly overlapping ovary. Ovary looping dorsoventrally around right intestinal caecum. Ootype and uterus not observed. Vagina dextroventral, located slightly anterior to body mid-length, composed of trumpet-shaped distal part and multi-coiled vaginal tube with proximal fork. Vaginal canal and seminal receptacle not observed. Vitellarium follicular, extending from level of oesophagus to near haptor; absent in region of other reproductive organs. Transverse vitelline ducts not observed. Testis postovarian. Vas deferens looping around left intestinal caecum; seminal vesicle a simple dilation of distal vas deferens, located to left and posterior to MCO. Two prostatic reservoirs unequal in size. MCO composed of articulated copulatory tube and accessory piece. Copulatory tube U-shaped, with thin, sharply S-shaped proximal portion (2 distinct bends in proximal third), separated by submedial spine from narrowed distal part, usually curved outwards at tip. Accessory piece with 3 rami: proximal ramus articulated to base; distal ramus largest, forming V-shaped structure with proximal one; medial ramus arising externally to their junction, with frilled terminal margin.

Haptor armed with dorsal and ventral anchor–bar complexes and 7 pairs of hooks. Ventral and dorsal anchors dissimilar in shape. Ventral anchors with terminally flattened base and elongate curved shaft with slight undulation near junction with short point. Dorsal anchors with broad fan-shaped base and elongate curved shaft with slight undulation near junction with short point. Ventral bar saddle-shaped, with 2 large submedial protuberances along anterior margin and posteromedial process; ends slightly recurved posteriorly. Paired dorsal bar robust, with markedly broad, bulbous medial end. Hooks similar in shape and size; each with slightly erect, hooked thumb; shank slightly inflated along inner side except for curved terminal portion; FH loop nearly entire shank length.

Measurements: Body 1040 (582–1416; n = 5) long; greatest width 235 (199–300; n = 5). Pharynx 99 (87–112; n = 5) long, 92 (88–99; n = 5) wide. Haptor 95 (70–117; n = 5) long, 160 (112–200; n = 5) wide. Ventral anchor 67 (65–70; n = 5) long; base width 29 (27–32; n = 5). Dorsal anchor 70 (67–73; n = 5) long; base width 34 (33–35; n = 5). Ventral bar 76 (71–81; n = 5) long. Paired dorsal bar 55 (53–58; n = 5) long. Hooks 14 (14–15; n = 3) long. MCO – tube curved length 98 (95–101; n = 5); tube height 40 (37–42; n = 5).

Remarks: This species is described here based on 6 specimens collected from Catostomus ardens in Idaho by Delane Kritsky (1989), to whom we are grateful for kindly providing the material. The specimens were of sufficient quality to confirm their status as a new species; however, some internal characters could not be assessed, precluding the preparation of a complete body illustration. Pseudomurraytrema kritsdelani n. sp. is most similar to P. ardens n. sp., both of which parasitize the gills of C. ardens. A detailed comparison and differential diagnosis are provided in the Remarks section for P. ardens n. sp. Although molecular data are not available for P. kritsdelani n. sp., and we acknowledge that some differences between these 2 species may reflect intraspecific variability or artefacts of fixation, the observed morphological distinctions are consistent across most available specimens. We therefore regard the 2 taxa as representing separate species, while recognizing that future sequencing of P. kritsdelani n. sp. will be essential to confirm this taxonomic distinction.

Pseudomurraytrema species parasitizing species of Moxostoma (Moxostomatini)

Pseudomurraytrema cf. coosense Rogers, 1969 (Figure 10)

Type host and locality: Moxostoma duquesnei (Lesueur) – Coosawattee River (Gilmer Co.), Georgia.

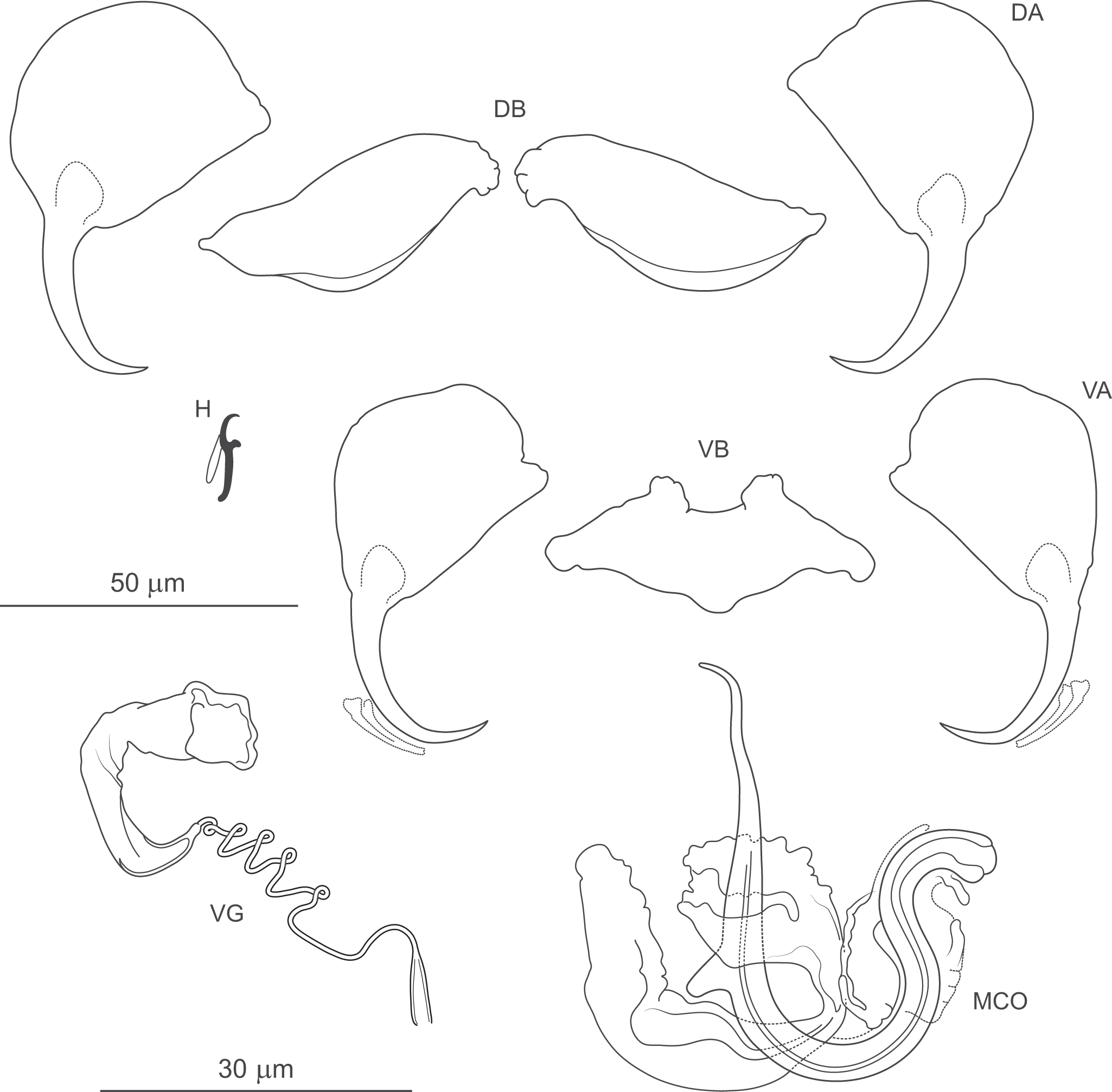

Figure 10. Pseudomurraytrema cf. coosense ex Moxostoma macrolepidotum (Wisconsin): VA – ventral anchor, VB – ventral bar; DA – dorsal anchor; DB – dorsal bar; H – hook; MCO – male copulatory organ; VG – vagina.

Current records: Moxostoma macrolepidotum (Lesueur) – Mississippi River, Main Channel (43°51′35.94″N; 91°18′8.65″W), Wisconsin (6 July 2022).

Previous records: See type host species and locality (Rogers Reference Rogers1969); Hillabee Creek (Clay Co.), Alabama (Rogers Reference Rogers1969).

Site of infection: Gills.

Prevalence and intensity of infection: 67% (2 fish infected/3 fish examined); 1 parasite per infected host.

Voucher specimens: One hologenophore (USNM 1762086).

Specimens studied for comparison: P. coosense (Rogers Reference Rogers1969) (USNM 1366719, paratype).

Measurements: Haptor 167 (n = 1) long, 275 (n = 1) wide. Ventral anchor 99 (n = 1) long; base width 37 (n = 1). Dorsal anchor 101 (n = 1) long; base width 38 (n = 1). Ventral bar 92 (n = 1) long. Paired dorsal bar 83 (n = 1) long. Hooks 15 (14–15; n = 1) long. MCO – tube curved length 96 (94–97; n = 2); tube height 39 (n = 2).

Remarks: Pseudomurraytrema coosense was described by Rogers (Reference Rogers1969) from the gills of M. duquesnei collected in the Coosa River system in Alabama and Georgia. It clearly differs from all other congeners parasitizing Moxostoma species by having anchors with a markedly elongate, bent shaft and a short, recurved point (vs more arched and moderately long or short shaft and point in P. fergusoni, Pseudomurraytrema fluviatile, Pseudomurraytrema milleri and Pseudomurraytrema swinglei). Examination of 1 paratype (USNM 1366719) confirmed that the measurements and illustration of the specimen correspond to the original description. While the Wisconsin specimens generally conform to the morphological features described for P. coosense, they are tentatively assigned to this species as P. cf. coosense. This conditional assignment is based on the following considerations: (1) the anchors of the Wisconsin specimens are longer than those reported in the original description (ventral anchor: 99 vs 55–84; dorsal anchor: 101 vs 56–72); (2) the ventral bar in the Wisconsin specimens is slightly deformed due to mechanical distortion during trisection of the specimen for DNA analysis and is therefore not suitable for detailed comparison; and (3) the specimens were collected from a different host (M. macrolepidotum) and in a different river system (Mississippi River drainage, Wisconsin) than the type locality (Coosawattee River, Georgia). Although the specimens are tentatively assigned to P. cf. coosense, they are compared here to P. milleri due to shared morphological features of the haptoral bars. In both species, the paired dorsal bar is subfusiform, and the ventral bar possesses a dorsally located membrane protruding as 2 processes from its anteromedial margin. However, the ends of the paired dorsal bar are uniformly narrowed in P. cf. coosense, whereas in P. milleri, the medial end is wider than the lateral one. In addition, the ventral bar of P. cf. coosense lacks the posteromedial shield-like process present in P. milleri.

Until more comprehensive material becomes available, including specimens in better condition and from a broader host and geographic range, the identification as P. cf. coosense should be retained.

Pseudomurraytrema milleri Mergo & White, 1982 (Figure 11)

Type host and locality: Moxostoma anisurum (Rafinesque) – Salt Creek, Eagle Twp. (Vinton Co.), Ohio.

Figure 11. Pseudomurraytrema milleri ex Moxostoma anisurum (Wisconsin): VA – ventral anchor, VB – ventral bar; DA – dorsal anchor; DB – dorsal bar; H – hook; MCO – male copulatory organ; VG – vagina.

Current records: Moxostoma anisurum – Mississippi River, Main Channel (43°51′35.94″N; 91°18′8.65″W), Wisconsin (7 July 2022).

Previous records: No other records, apart from the original description by Mergo and White (Reference Mergo and White1982).

Site of infection: Gills.

Prevalence and intensity of infection: 100% (2 fish infected/2 fish examined); 6–22 parasites per infected host.

Voucher specimens: Three hologenophores (USNM 1762109–1762111); 3 morphological vouchers (USNM 1762112).

Specimens studied for comparison: P. milleri (Mergo and White Reference Mergo and White1982) (USNM 1371986, 3 paratypes).

Measurements: Body 2526 (1697–3544; n = 4) long; greatest width 373 (337–448; n = 4). Pharynx 148 (128–160; n = 4) long, 124 (107–148; n = 4) wide. Haptor 154 (141–161; n = 3) long, 242 (218–273; n = 3) wide. Ventral anchor 59 (55–63; n = 7) long; base width 27 (25–27; n = 7). Dorsal anchor 71 (68–74; n = 7) long; base width 32 (31–33; n = 7). Ventral bar 66 (62–72; n = 7) long. Paired dorsal bar 63 (58–67; n = 7) long. Hooks 15 (14–15; n = 5) long. MCO – tube curved length 109 (106–112; n = 5); tube height 44 (42–46; n = 5).

Remarks: While in need of redescription, P. milleri differs from its congeners primarily by possessing a saddle-shaped ventral bar with a shield-like posteromedial process that is divided medially (in other species, this process is either knob-like or absent). Mergo and White (Reference Mergo and White1982) described this process as consisting of 2 closely associated plates. The original illustrations of the sclerotized structures are highly schematic (likely drawn freehand) and are insufficient for accurate species identification. In their description of P. milleri, Mergo and White (Reference Mergo and White1982) characterized the paired dorsal bar as ‘angular’ and depicted it with 1 end angularly recurved. The morphology of the paired dorsal bar in P. milleri is somewhat variable among our specimens, which may reflect artefacts of mounting technique. Its shape ranges from relatively straight to recurved in the lateral third. The latter condition may correspond to the character reported by Mergo and White (Reference Mergo and White1982, their Figure 3), although these authors illustrated the paired dorsal bar with both ends similarly tapered, whereas in our specimens, the medial end is distinctly broader than the lateral one. Additionally, P. milleri resembles P. swinglei in the morphology of the ventral and dorsal anchors, which in both species possess a shaft exhibiting slight undulation near its junction with the point. This undulation was neither described nor illustrated in the original description of P. milleri (Mergo and White Reference Mergo and White1982; Figures 1 and 4). Moreover, the illustration of the hook by Mergo and White (Reference Mergo and White1982) does not accurately reflect the morphology typical of Dactylogyridea. The thumb is entirely absent in their Figure 2, rendering the illustration unsuitable for diagnostic purposes. In this character, P. milleri resembles P. kritsdelani n. sp., as both species possess hooks with a shank that is slightly inflated along the inner side, except for the curved terminal portion (see Figure 7). However, the hook of P. milleri differs from that of P. kritsdelani n. sp. by having a thumb that is robust and projects perpendicularly from the shank, whereas in P. kritsdelani n. sp. the thumb is more slender and erect.

Comparison of 3 paratypes (USNM 1371986) with our specimens collected from the same host species in Wisconsin revealed no morphological differences in the sclerotized structures of the haptor. However, comparison of the morphology of the MCO was not possible due to the poor condition of the available paratypes.

The occurrence of P. milleri on Moxostoma anisurum in Wisconsin represents a new geographic record for this species.

Pseudomurraytrema fluviatile Rogers, 1969 (Figure 12)

Type host and locality: Moxostoma carinatum (Cope) – Cahaba River (Perry Co.), Alabama.

Figure 12. Pseudomurraytrema fluviatile ex Moxostoma erythrurum (Wisconsin): VA – ventral anchor, VB – ventral bar; DA – dorsal anchor; DB – dorsal bar; H – hook; MCO – male copulatory organ; VG – vagina.

Current records: Moxostoma erythrurum (Rafinesque) – Mississippi River, Main Channel (43°51′35.94″N; 91°18′8.65″W), Wisconsin (10 July 2022).

Previous records: See type host species and locality (Rogers Reference Rogers1969); Tallapoosa River (Elmore Co.), Tombigbee River (Sumter Co.), Alabama (Rogers Reference Rogers1969).

Site of infection: Gills.

Prevalence and intensity of infection: 100% (1 fish infected/1 fish examined); 10 parasites per infected host.

Voucher specimens: Two hologenophores (USNM 1762095, 1762096); 2 morphological vouchers (USNM 1762097).

Measurements: Body 1203 (1167–1284; n = 4) long; greatest width 198 (158–241; n = 4). Pharynx 98 (92–106; n = 3) long, 83 (81–85; n = 3) wide. Haptor 119 (81–152; n = 4) long, 201 (178–230; n = 4) wide. Ventral anchor 79 (75–84; n = 6) long; base width 32 (29–34; n = 6). Dorsal anchor 83 (81–87; n = 6) long; base width 36 (34–37; n = 6). Ventral bar 78 (72–86; n = 6) long. Paired dorsal bar 78 (72–88; n = 6) long. Hooks 14 (13–15; n = 4) long. MCO – tube curved length 92 (90–96; n = 4); tube height 39 (37–40; n = 4).

Remarks: Rogers (Reference Rogers1969) described P. fluviatile from M. carinatum in Alabama. Although his illustrations do not include the vagina and his depiction of the MCO is too schematic for reliable species differentiation, his drawings of the sclerotized structures of the haptor correspond well with our specimens collected from M. erythrurum in Wisconsin. The respective dimensions of the hard parts in our material are generally larger than those reported by Rogers (Reference Rogers1969), but mostly fall within the range provided in his original description of P. fluviatile. A more pronounced difference was observed in the length of the paired dorsal bar, which is considerably greater in our specimens than that reported by Rogers (Reference Rogers1969) (72–88 vs 57–63). However, given the wide intraspecific variation in dorsal bar length observed across all species of Pseudomurraytrema examined in this study, we do not consider this difference sufficient to warrant recognition of a separate species at this time. Pseudomurraytrema fluviatile is most similar to P. swinglei. In both species, the anchors possess a moderately long, arcuate shaft and point; the paired dorsal bar is subtriangular; and the ventral bar is saddle-shaped with 2 pairs of anteromedial and 1 posteromedial processes. Pseudomurraytrema fluviatile differs from P. swinglei by the following characters: (1) a dorsal anchor with a crescent-shaped base (vs a base with a straight inner margin, not resembling a crescent, in P. swinglei), (2) dorsal and ventral anchors lacking distal shaft undulation (vs both anchors with distal shaft undulation in P. swinglei), (3) a ventral bar with small anteromedial processes (vs more prominent anteromedial processes in P. swinglei) and (4) a paired dorsal bar with a smoothly convex posterior margin (vs an angularly convex margin in P. swinglei).

The occurrence of P. fluviatile on the golden redhorse, Moxostoma erythrurum, from Wisconsin represents both a new host and a new locality record for this species.

Pseudomurraytrema swinglei Rogers, 1966 (Figure 13)

Type host and locality: Moxostoma duquesnei – Chewacla Creek (Lee Co.), Alabama.

Figure 13. Pseudomurraytrema swinglei ex Moxostoma congestum (Texas): VA – ventral anchor, VB – ventral bar; DA – dorsal anchor; DB – dorsal bar; H – hook; MCO – male copulatory organ; VG – vagina.

Current records: Moxostoma congestum (Baird & Girard) – Colorado River, between Austin and Bastrop (30°11′15.4″N 97°28′37.1″W), Texas (31 May 2023).

Previous records: No other records, apart from the original description by Rogers (Reference Rogers1966).

Site of infection: Gills.

Prevalence and intensity of infection: 100% (3 fish infected/3 fish examined); 1–12 parasites per infected host.

Voucher specimens: Three hologenophores (USNM 1762120–1762122); 2 morphological vouchers (USNM 1762123).

Measurements: Body 890 (n = 1) long; greatest width 98 (n = 1). Pharynx 100 (98–104; n = 5) long, 92 (88–93; n = 5) wide. Haptor 165 (155–186; n = 5) long, 292 (267–310; n = 5) wide. Ventral anchor 53 (51–55; n = 6) long; base width 23 (22–24; n = 6). Dorsal anchor 58 (56–59; n = 6) long; base width 27 (25–27; n = 6). Ventral bar 57 (55–59; n = 6) long. Paired dorsal bar 51 (47–54; n = 6) long. Hooks 13 (12–14; n = 6) long. MCO – tube curved length 90 (88–92; n = 6); tube height 37 (30–39; n = 6).

Remarks: The original description of Pseudomurraytrema swinglei by Rogers (Reference Rogers1966) generally agrees with the characters exhibited by our specimens. In Rogers’ Figure 2, the ventral bar is illustrated as saddle-shaped with 2 distinct anteromedial rectangular processes, which likely correspond to the 2 pairs of anteromedial processes observed in our specimens: 1 pair is rectangular and projects dorsally, while the other is rounded and protrudes from the ventral surface. These 2 pairs may overlap and appear as a single rectangular structure under low magnification. Pseudomurraytrema fluviatile also possesses a ventral bar with 2 pairs of anteromedial processes, but these are rounded and considerably smaller than those in P. swinglei. For a detailed comparison between P. swinglei and its closest congener, P. fluviatile, refer to the Remarks under the description of P. fluviatile.

The occurrence of P. swinglei on the grey redhorse, M. congestum, in Texas represents a new host and geographic record for this species.

Pseudomurraytrema fergusoni McAllister, Leis, Cloutman, Woodyard, Camus & Robinson, 2022 (Figure 14)

Type host and locality: Moxostoma pisolabrum – White River drainage, Black River, Black Rock (Lawrence Co.), Arkansas.

Figure 14. Pseudomurraytrema fergusoni n. sp. ex Moxostoma macrolepidotum (Wisconsin): VA – ventral anchor, VB – ventral bar; DA – dorsal anchor; DB – dorsal bar; H – hook; MCO – male copulatory organ; VG – vagina.

Current records: Moxostoma macrolepidotum – Mississippi River, Main Channel (43°51′35.94″N; 91°18′8.65″W), Wisconsin (11 July 2022).

Previous records: No other records, apart from the original description by McAllister et al. (Reference McAllister, Leis, Cloutman, Woodyard, Camus and Robison2022).

Site of infection: Gills.

Prevalence and intensity of infection: 100% (2 fish infected/2 fish examined); 1–3 parasites per infected host.

Voucher specimens: Two hologenophores (USNM 1762092, 1762093); 1 morphological voucher (USNM 1762094).

Measurements: Body 2620 (n = 1) long; greatest width 380 (n = 1). Pharynx 149 (n = 1) long, 135 (n = 1) wide. Haptor 290 (n = 1) long, 440 (n = 1) wide. Ventral anchor 82 (n = 1) long; base width 39 (n = 1). Dorsal anchor 82 (n = 1) long; base width 45 (n = 1). Ventral bar 102 (n = 1) long. Paired dorsal bar 118 (n = 1) long. Hook 15 (n = 1) long. MCO – tube curved length 46 (45–47; n = 2); tube height 27 (26–27; n = 2).

Remarks: Pseudomurraytrema fergusoni was recently described and sequenced by McAllister et al. (Reference McAllister, Leis, Cloutman, Woodyard, Camus and Robison2022) from the gills of M. pisolabrum in Arkansas. This species differs markedly from its congeners and from all other members of Pseudomurraytrematidae by the unique morphology of both the MCO and the vagina. A characteristic feature observed in all previously known members of the family is the U-shaped configuration of the copulatory tube, which resembles the frame of a lyre. In P. fergusoni, however, the distal end of the copulatory tube appears truncated, which represents a striking departure from the curved and distinctly narrowed distal end observed in other pseudomurraytrematids. In addition, the base of the copulatory tube is poorly defined and merges with the proximal portion of the accessory piece, forming a bulbous structure. This contrasts with other species of the family, in which the base is S-shaped and remains separate from the accessory piece.Another distinguishing feature of P. fergusoni is the presence of a tubular vagina located in a small bulb that protrudes from the right body margin. In contrast, all other known members of Pseudomurraytrematidae possess a vagina composed of a weakly sclerotized distal funnel and a proximal coiled tube, as noted in the family diagnoses provided by Kritsky et al. (Reference Kritsky, Mizelle and Bilqees1978) and Beverley-Burton (Reference Beverley-Burton, Margolis and Kabata1984). Moreover, in all Pseudomurraytrema species examined during the present study, the vagina is situated on the dextroventral side of the body, not at the margin as in P. fergusoni.

The original description of P. fergusoni, supported by drawings and microphotographs of the haptoral and copulatory sclerotized structures, is generally adequate. However, McAllister et al. (Reference McAllister, Leis, Cloutman, Woodyard, Camus and Robison2022) illustrated the hooks as having a straight, proximally extending shank and an upright thumb. Based on their illustrations (Figures 1D, 3C, D), it appears that these authors overlooked the proximal knob-like termination of the shank. Examination of GAP-fixed specimens collected during the present study revealed that P. fergusoni possesses hooks with the shank inflated along its inner margin, except for the proximal third, which ends in a curved, knob-like base. The thumb of the hook is dome-shaped and either slightly erect or projecting perpendicularly from the shank (Figure 7). The ventral bar in our specimens of P. fergusoni from M. macrolepidotum exhibits more pointed lateral ends than those illustrated by McAllister et al. (Reference McAllister, Leis, Cloutman, Woodyard, Camus and Robison2022); however, this difference may be attributed to variation in the orientation of the ventral bar in the compared specimens. McAllister et al. (Reference McAllister, Leis, Cloutman, Woodyard, Camus and Robison2022) also reported that the vagina was not observed. In their description, they stated that measurements were based on 10 formalin-fixed specimens (holotype and 9 paratypes). However, it remains uncertain how many of these individuals were examined in detail for internal morphology. In the present study, the vagina was not detected in 1 of the 3 examined specimens, despite the presence of the MCO in all of them.

The occurrence of P. fergusoni on M. macrolepidotum in Wisconsin represents a new host and geographic record for this species.

Pseudomurraytrema species parasitizing Erimyzon claviformis and Minytrema melanops (Erimyzonini)