Introduction

Women politicians have made some substantial gains in access to the highest political office in recent decades. Between 1960 and 1969, for example, women constituted roughly 3% of the chief executives in the world’s electoral democracies. By the decade of the 2010s, that figure had increased to roughly 15%. Reaching the highest office, however, comes with some challenges. Recent research notes that women often gain high political posts in more difficult societal conditions than their male counterparts (labeled as a “glass cliff”; see, e.g., Beckwith Reference Beckwith2015; O’Brien Reference O’Brien2015; Reyes-Householder and Thomas Reference Reyes-Householder and Thomas2021). Cross-national studies of presidents in Third Wave democracies find that female leaders’ approval ratings are lower than men’s, and that their ratings decline more than their male counterparts’ over the course of their term (Carlin et al. Reference Carlin, Carreras and Love2020; Reyes-Householder Reference Reyes-Householder2020).

The research thus raises several questions about women’s reelection to the highest office. Is reelection gendered? Are women presidents and prime ministers (PMs) less likely to win a new term than their male counterparts? How do economic conditions on their watch, such as the growth rate or inflation, affect their odds of winning? Does a high level of corruption in the executive branch, or a high level of domestic conflict, reduce women’s chances for a new term more than their male counterparts?

The answers are far from clear. While a growing body of research explores gender and reelection below the level of presidents/PMs, there is as yet no cross-national comparative study addressing the issue for chief executives. A few studies have tracked leaders’ duration in office, but offer conflicting conclusions. Some evidence points to shorter durations for women (Muller-Rommel and Vercesi Reference Muller-Rommel and Vercesi2017; Worthy Reference Worthy2016), while other evidence suggests that women and men serve for about the same length of time on average (Jalalzai Reference Jalalzai2008; Reference Jalalzai2013).

There are many possible explanations for the divergent conclusions. Studies differ in the choice of time period, countries, and level of office, which suggests that other events or political institutional rules may be affecting the results. For example, differing rules about term limits and the different lengths of election cycles can affect cross-national comparisons of duration for presidents and PMs. Similarly, the length of time a country has been a democracy can play a significant role in leader tenure. Possible time in office would necessarily be shorter in countries that experienced relatively recent transitions to democracy.

For these reasons, we provide a new cross-national, comparative analysis of gender and reelection in top leadership positions. We draw on data about male and female chief executives in 98 electoral democracies across the Americas, Europe, Asia, and Africa from 1960 to 2023. Rather than looking at the duration of leaders’ tenure, we ask whether eligible presidents/PMs win the next election after entering office. We assess whether and how key features of the institutional context and of leaders’ performance in office affect the odds of gaining a new term. And we explore whether these factors have differential effects for men vs. women leaders.

To preview the main results, we find that women presidents and PMs have about the same odds of winning a new term as their male counterparts. When we turn attention to the effects of leaders’ performance in office, our results suggest that the chance of reelection improves for both men and women leaders when the economy is growing, and declines when corruption in the executive branch is more extensive. Men fare somewhat worse than women do when inflation is higher, and when the country experiences more domestic conflict. We also find that women leaders run at a somewhat higher rate than their male counterparts.

Our research makes a number of important contributions to the field. First, by focusing on reelection rather than duration in office, we are able to overcome the challenges that come with the wide array of terms, rules about term limits, and changing executive regime types across the world. Second, most of the literature to date has focused on how women enter the chief executive’s office; to the best of our knowledge, ours is the first comparative cross-national study to analyze the determinants of their ability to win a new term. Finally, for those women who have made it into the rarefied post of chief executive, our findings suggest that, going forward, they face fewer barriers to reelection. Once women obtain office, they have about the same chances—all else being equal—to be reelected to that office.

Gender, Election, and Reelection

Comparative research on gender and elections has typically focused on entry into office, and especially on the factors that result in female underrepresentation. Women have been found to be less inclined to step into the political arena; to have fewer resources when they do; and to face greater skepticism from voters and party officials about their competence and electability (see, e.g., Bjarnegard Reference Bjarnegard2013; Bjarnegard and Kenny Reference Bjarnegård and Kenny2016; Fox and Lawless Reference Fox and Lawless2004; Kenny and Verge Reference Kenny and Verge2016). The obstacles are even more pronounced at the top of the political hierarchy: the post of chief executive tends to be the most gendered. Limited numbers of women in feeder positions, such as legislatures and cabinet ministries, mean that the pool of potential female candidates is typically small. And expectations about political leadership tend to emphasize stereotypically masculine traits such as toughness and assertiveness (Jalalzai Reference Jalalzai2013; Thames and Williams Reference Thames and Williams2013; Verge and Astudillo Reference Verge and Astudillo2019). When women do manage to reach high executive office, they are less likely to gain entry where access is by direct vote and power is concentrated in a single position, as in presidential systems. Their chances are seen as much better for positions where access is by appointment, and where power is shared, as prime ministers in parliamentary systems or second-level officials where the main power-holder is male (Jalalzai Reference Jalalzai2008; Reference Jalalzai2013; Jalalzai and Krook Reference Jalalzai and Krook2010; Jalalzai and Rincker Reference Jalalzai and Rincker2025; Thames and Williams Reference Thames and Williams2013; Wiltse and Hager Reference Wiltse and Hager2021).

However, while research on candidate entry tends to highlight the constraints on women’s access to office, studies of gender and reelection to offices below the level of national leader paint a somewhat different picture.Footnote 1 Women office holders have already entered the arena, so either had no reluctance about seeking office initially or overcame it. They have already acquired the resources needed to gain office and have demonstrated the ability to compete. Thus, female incumbents in many cases have been shown to fare as well as their male counterparts when seeking reelection. To note a few studies, Welch and Studlar’s (Reference Welch and Studlar1988) research on elections in English county councils showed that other things being equal, female members polled about the same percentages of votes as their male counterparts. Shair-Rosenfield (Reference Shair-Rosenfield2012) found that women MPs in Indonesia won at roughly the same rate as men. Shair-Rosenfield and Hinojosa (Reference Shair-Rosenfield and Hinojosa2014) discovered that female and male office holders in Chile’s parliament and local governments had similar rates of reelection. And Sevi (Reference Sevi2023) found that women MPs in Canada were as likely as men to win a new term. Other, indirect evidence suggests, though, that women in some contexts have fared worse. For example, Verge and Astudillo’s (Reference Verge and Astudillo2019) study of regional-level prime ministers in Austria, Germany, Spain, and the U.K. showed that incumbent women faced lower odds of being renominated. Gagliarducci and Paserman’s (Reference Gagliarducci and Paserman2012) analysis of local governments in Italy revealed that women mayors had shorter tenures in office than those for men.

We know much less about gender and reelection for leaders at the national level. Existing evidence about their prospects is only indirect. For example, research focused on the glass cliff suggests that female leaders tend to come to office in more challenging societal conditions, and thus begin their term with a handicap (see, e.g., Beckwith Reference Beckwith2015; O’Brien Reference O’Brien2015; Reyes-Householder and Thomas Reference Reyes-Householder and Thomas2021). Studies based on approval ratings suggest further handicaps. Reyes-Householder (Reference Reyes-Householder2020) found that ratings of women presidents in Latin American democracies are significantly lower than those for men. Carlin, Carreras, and Love (Reference Carlin, Carreras and Love2020) showed that female presidents in Latin American and East Asian democracies enter office with lower ratings and experience more decline in ratings over the course of their term than men do. When attention has turned to leader tenure, the conclusions are more mixed. Two studies of prime ministers in European democracies found that women remain in office for fewer months than their male counterparts (Muller-Rommel and Vercesi Reference Muller-Rommel and Vercesi2017; Worthy Reference Worthy2016). Research on presidents/PMs among the world’s democracies and autocracies showed that women and men spend roughly equal amounts of time in office (Jalalzai Reference Jalalzai2008; Reference Jalalzai2013).Footnote 2

Yet women presidents and PMs have competed for and won office, and have resources, networks, and name recognition, so their odds of winning reelection might be as favorable as those for men. And as research on the “Jackie and Jill Robinson effect” has shown, gender biases and institutional obstacles can mean that to achieve these offices, women need to be especially capable and hardworking (Anzia and Berry Reference Anzia and Berry2011; Bauer Reference Bauer2020; Kroger and Huffelman Reference Kroger and Huffelmann2022; Lazarus and Steigerwalt Reference Lazarus and Steigerwalt2018).Footnote 3 Thus, women who become presidents or prime ministers are likely to have the skills and experience needed to win reelection.

Theory and Hypotheses

The indirect evidence thus implies that women chief executives are either disadvantaged when it comes to reelection, or have about the same chances as men do to win a new term. We provide a more direct test to assess whether:

H1a: Women chief executives are likely to have lower odds of reelection than their male counterparts; or

H1b: Women chief executives are likely to have about the same odds of reelection.

We identify three key factors that could condition their prospects. The first is the type of executive office, what Shugart and Samuels (Reference Shugart and Samuels2010) label as executive format. Women’s reelection prospects should be stronger if the post is filled by appointment; i.e., if the chief executive is a prime minister rather than a directly elected president (Jalalzai Reference Jalalzai2008; Reference Jalalzai2013; Jalalzai and Krook Reference Jalalzai and Krook2010; Thames and Williams Reference Thames and Williams2013; Wiltse and Hager Reference Wiltse and Hager2021). In contrast to the pathways for presidential candidates, recruitment of prime ministers hinges far more on their history of service to their party. Shugart and Samuels (Reference Shugart and Samuels2010) show, for example, that prime ministers in democracies typically have substantially more experience than presidents in posts as MP, party official, or cabinet minister. Women can thus work their way up through the party ranks. The post of prime minister also requires more collaboration with others in the party, legislature, and cabinet, and typically with other parties in coalitions. And women are considered to have an advantage in posts that hinge on the ability to collaborate (Jalalzai Reference Jalalzai2008, Reference Jalalzai2013; Jalalzai and Krook Reference Jalalzai and Krook2010). Key mechanisms of accountability could also favor female candidates: prime ministers’ tenure depends on continued support from their party and the legislature, and PMs can be removed more easily than directly elected presidents. PMs are thus typically more constrained than presidents, which can make other party officials and coalition partners less hesitant to back female candidates (Jalalzai Reference Jalalzai2008; Reference Jalalzai2013; Jalalzai and Krook Reference Jalalzai and Krook2010).

H2: Women leaders are more likely than men to gain a new term when selection is by appointment rather than direct election.

A second factor that could influence women leaders’ prospects for reelection is their mode of initial entry into office. Leaders who come to office as replacements, appointed between elections, appear less likely to win the next election. Replacements gain their posts when a predecessor leaves, due to resignation, severe illness/death, or interruption. In Estonia, for example, Kaja Kallas (2021–2024) became prime minister when her predecessor’s coalition unraveled. In Malawi, Vice President Joyce Banda (2012–2014) became president after her predecessor, Bingu wa Mutharika, died in office. Replacements enter without the boost of an electoral victory and with less political capital than chief executives who gain the position through the polls (Worthy Reference Worthy2016). If women achieve office via replacement rather than election, their odds of retaining office should be lower.

H3: Women leaders are less likely than men to gain a new term if they entered the office via replacement of a predecessor rather than by election.

A third factor that could affect women leaders’ odds of reelection is expectations about their performance in office (see, e.g., O’Neill, Pruysers, and Stewart Reference O’Neill, Pruysers and Stewart2021; Verge and Astudillo Reference Verge and Astudillo2019). Gender stereotypes can have a substantial influence on the way male and female competence and performance are evaluated. To note one such difference, public opinion ratings of male leaders typically hinge on issues seen to require toughness, such as security, while ratings of women leaders hinge on stereotypes of rectitude, such as those relating to corruption.

The strongest evidence for the influence of stereotypes occurs with respect to political corruption. As Barnes and Beaulieu (Reference Barnes and Beaulieu2014), Carlin et al. (Reference Carlin, Carreras and Love2020), and Reyes-Householder (Reference Reyes-Householder2020) suggest, women leaders are often held more accountable for high levels of corruption because morality and honesty are more associated with women than with men.Footnote 4 Higher levels of corruption during their initial years in office should therefore have a stronger negative effect on women leaders’ odds of winning reelection than on their male counterparts.

H4: Women leaders are less likely than males to gain a new term when executive branch corruption is more extensive.

Women are also typically considered to be less competent than men in addressing questions involving crime and domestic conflict (Carlin et al. Reference Carlin, Carreras and Love2020; Dolan and Lynch Reference Dolan and Lynch2016; Holman et al. Reference Holman, Merolla and Zechmeister2016). As a result, women leaders may find it difficult to rally the public around the flag in the face of domestic conflict and are more likely to be judged as lacking the ability to deal with rising conflict at home. Women leaders should thus be less likely to be reelected than their male counterparts when there are high levels of domestic conflict.

H5: Women leaders are less likely than men to gain a new term when domestic conflict is more extensive.

Economic performance could also have an effect, but compared to corruption and domestic conflict, it is less clear whether men and women leaders are judged differently for it. There is a long literature suggesting that economic performance influences how the public votes (see Nadeau et al. Reference Nadeau, Lewis-Beck and Bélanger2013 for an overview). However, there are few consistent findings to indicate whether women leaders are affected differentially by positive or negative economic outcomes. On one hand, some scholars note the tendency not to appoint women to positions of power over the economy, suggesting that they are viewed as less capable in economic matters. If women are considered less capable, they may be less likely to win reelection in bad economic times. They might receive more of the blame when inflation is high or economic growth wanes. On the other hand, Carlin et al. (Reference Carlin, Carreras and Love2020) conclude that the growth rate makes little difference in public support for female vs. male leaders, and that ratings for both suffer when inflation is high. For these reasons, we have mixed expectations about how economic conditions might affect women’s and men’s odds of reelection.

H6a: Women leaders are less likely than men to gain a new term when GDP per capita growth is lower; or

H6b: Women leaders have about the same odds as men of gaining a new term when GDP per capita growth is lower.

H7a: Women leaders are less likely than men to gain a new term when the inflation rate is higher; or

H7b: Women leaders’ odds of gaining a new term are about the same as those for men when the inflation rate is higher.

Data and Methods

We focus on presidents and prime ministers in electoral democracies who were in office between 1960 and 2023. Our units of analysis are the chief executives, the leaders labeled as the “effective executive” in each country by the Archigos project (Goemans et al. Reference Goemans, Gleditsch and Chiozza2009).Footnote 5 Since the Archigos data stop at 2015, we updated the list of leaders through December 31, 2023.Footnote 6 We analyze reelection in the first vote after leaders entered office, for the presidents/prime ministers who were eligible to run. Leaders were not considered eligible if they had reached their term limit; had left office due to death or severe illness; were banned from running; or had their term in office interrupted prematurely. Interruptions include early exits from office due to removal by the legislature, the courts, or another government body; resignations in the face of such a procedure; and resignation/abandonment of office due to personal scandal or mass public unrest. For example, Brazilian President Fernando Collor (1990–1992) resigned during an impeachment procedure in the legislature. South Korean President Park Geun-hye (2013–2017) was impeached and removed from office. In contrast, losing a party leadership contest or having a coalition dissolve are not treated as interruptions.

Countries are included if they were counted as electoral democracies for three consecutive years or more by Boix, Miller, and Rosato (BMR; Reference Carles, Miller and Rosato2018).Footnote 7 BMR uses three main criteria: (1) whether a country holds elections for the top post, (2) for the legislature, and (3) whether the elections feature more than one party.Footnote 8 Since these data, too, end with 2015, we updated them with ratings on electoral democracies from Freedom House through the end of 2023. We exclude small states due to lack of data, as well as countries with collective and/or rotating chief executives (Chile 1960–66; Bosnia Herzegovina; and Switzerland).

Altogether, the initial sample consists of 940 non-interim presidents/PMs, of whom 640 were eligible to run for reelection. Among the 640, 46 (7.2%) are female, and 594 are male. As in other recent cross-national research on chief executives, the number of women is thus relatively small. For example, Carlin et al.’s (Reference Carlin, Carreras and Love2020) study of male and female presidents’ approval ratings in Latin America and East Asia includes ten cases of female presidents. Reyes-Householder’s (Reference Reyes-Householder2020) analysis of male and female presidents’ approval ratings and corruption in Latin America includes six women presidents. Verge and Astudillo’s (Reference Verge and Astudillo2019) research on regional-level chief executives in Western Europe assesses renomination for 366 regional leaders, of whom 49 were women. We believe that our sample is sufficient for a first analysis of gender and reelection for presidents/PMs. It does, though, mean that some questions that might be of interest, such as whether patterns of reelection differ by region, cannot be addressed; there are too few eligible women leaders in most regions to generate reliable statistical results.

Our primary dependent variable is whether the president/PM wins reelection in the first contest after entering office (1 = reelected; 0 = not reelected). While some chief executives have gone on to win a third or fourth consecutive term, they are almost all prime ministers. Virtually all eligible presidents in our sample were limited to no more than two consecutive terms. We therefore focus on the first opportunity for reelection for both presidents and prime ministers.

We use the term “won” here to mean gaining a new term in office. For presidents, it refers to garnering a plurality or majority of the vote.Footnote 9 For prime ministers, it means being appointed to a new term, whether or not their party receives the largest share of votes or seats. Prime ministers can emerge as chief executive of a coalition or minority government even if their party placed second or third or even lower in vote or seat totals.

We do not analyze the length of a leader’s term in office, for several reasons. Many countries with directly elected presidents have changed term limits over time, altering the length of terms and/or the number that can be served consecutively. In France, for example, the presidential term was changed from seven to five years beginning with the election of Jacques Chirac in 2002. Several countries in Latin America changed from a single- to a two-term limit during the timeframe we analyze here (Cheibub and Medina Reference Cheibub, Medina, Baturo and Elgie2019; Ginsburg and Elkins Reference Ginsburg, Elkins, Baturo and Elgie2019). Others, such as Moldova and Slovakia, have shifted between direct and indirect selection of the president, so some of their leaders have been term-limited while others have not. And some countries have had shorter democratic spells than others, so possible duration in office depends in part on how long the country has been democratic. As a result, the length of time in office is not necessarily comparable across countries or even from one leader to the next within the same country.

We include several key covariates. Female is coded 1 for females and 0 for males. Executive format is captured by direct election: 1 = chief executive is selected by direct popular vote (a president); 0 = selection by the legislature (a prime minister). Entry type indicates whether the president/PM came into office via an election (1) or as a replacement between elections (0).

Our measures for leaders’ performance in office include the economic growth rate and the inflation rate (logged) from World Development Indicators; an index of executive branch corruption from V-Dem (high = more corruption); and an index of domestic conflict (logged) from the Cross-National Time Series data project (high = more conflict).Footnote 10 All four indicators are lagged one year. Since the raw data for these indicators are measured on different scales, we converted them to deciles to facilitate comparisons.

We also add three controls. As in previous studies of gender and high executive office, we include the percent of women in the legislature to indicate the presence of other elected female office holders (cf. Barnes and O’Brien Reference Barnes and O’Brien2025; Jalalzai and Rincker Reference Jalalzai and Rincker2025; Krook and O’Brien Reference Krook and O’Brien2012; Thames and Williams Reference Thames and Williams2013; Wiltse and Hager Reference Wiltse and Hager2021). To avoid confounding this variable with the presence of a female leader, it is measured three years before the leader entered office. We also control for leaders’ party “base,” their party’s share of the vote in the last legislative election before entry into office.Footnote 11 Another control indicates the time period when the president/PM entered office. As several researchers have noted, women’s access to high office shifted in the decades from the 1990s and early 2000s, which suggests some key changes in political contexts over time (Beckwith Reference Beckwith2015; Jalalzai, Reference Jalalzai2013; Jalalzai and Krook Reference Jalalzai and Krook2010). We thus include a control for the decade when the leader became president/PM. Descriptives for main variables are included in Appendix A.

Turning to the question of statistical analysis, reelection raises a potential problem of selection bias, since not all eligible presidents/PMs run.Footnote 12 We utilize a Heckman two-step selection procedure to address this issue: step one estimates a probit model for selection (i.e., whether a leader runs); and step two incorporates that information to model the outcome—whether the leader wins (cf. Shair-Rosenfield and Hinojosa Reference Shair-Rosenfield and Hinojosa2014). The procedure requires inclusion of a covariate in the selection model that is correlated with selection but not with the outcome. For that, we add a covariate to tap alternative opportunities for national elective office, whether the country has a bicameral legislature (1 = yes; 0 = no).Footnote 13

We also employ matching to tease out the effect of gender on leaders’ chances of winning a new term (cf. Shair-Rosenfield and Hinojosa Reference Shair-Rosenfield and Hinojosa2014). Statistical analyses can be biased if the sample is unbalanced, i.e., if the women differ substantially from the men on key covariates. We use matching to create more balance between female and male presidents/PMs. We use two forms of matching, propensity score and kernel, and both yield similar results.

Analysis

The percentages of women and men leaders who were eligible to run and who won reelection are presented in Figure 1. As noted earlier, our initial sample includes 940 non-interim presidents/PMs, of whom 640 were eligible to run. Figure 1 reveals that among the 940 non-interim leaders, roughly equal proportions of female and male leaders were eligible. And among the 640 eligibles, roughly equal proportions won a new term.

Figure 1. Eligibility and winning a new term by leader gender.

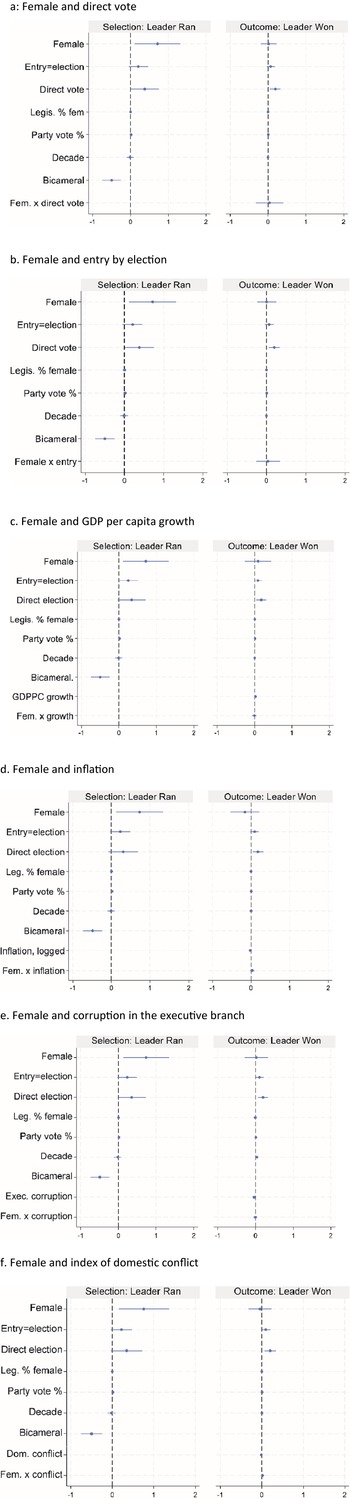

Turning to our Heckman analysis, Figure 2 presents six models, to test arguments about the effects of direct popular election (Figure 2a); type of entry into office (Figure 2b); the GDP per capital growth rate (Figure 2c); the inflation rate (Figure 2d); the extent of executive branch corruption (Figure 2e); and the extent of domestic conflict (Figure 2f). Each model also includes an interaction term for leader gender by each of these indicators.

Figure 2. Heckman selection models for reelection, point estimates with 95% confidence Intervals.

Across all models in Figure 2, the outcome results reveal that women leaders win a new term at roughly the same rate as men. The figures also show that on average, leaders win more often when the selection procedure is by direct popular vote. They also win more often if their party gained a higher share of the vote in the previous legislative election. With respect to performance in office, Figure 2c suggests that presidents/PMs generally fare better when the economy is growing, and fare worse when inflation is high and executive branch corruption is more extensive (Figures 2d and 2e, respectively). Leaders also face somewhat lower odds of reelection when there is more domestic conflict (the coefficient is significant at p < 10).

The interaction terms between gender and each of the indicators in Figure 2 are all non-significant at p ≤ .05.Footnote 14 However, graphs of their predicted probabilities in Figures 3a–f suggest that while some factors have similar influences on female and male leaders, others appear to have different effects. There is little difference between men’s and women’s leaders’ odds of reelection when it comes to competing in a direct popular vote (Figure 3a) or when it comes to their mode of initial entry into office (Figure 3b). GDP per capita growth (Figure 3c) appears to have a positive effect on reelection for both men and women leaders, while extensive corruption in the executive branch lowers the odds for both (Figure 3c). In contrast, inflation and domestic conflict seem to lower the odds only for male leaders (Figures 3d and 3f).Footnote 15 Women manage to win when both are higher, possibly due to the fact that a larger share of women leaders have come to power in countries where there is more instability (as, for example, in Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and the Philippines).

Figure 3. Predicted probabilities for interaction terms, 95% confidence intervals.

All told, we find little evidence of a gender gap in winning reelection for presidents and PMs (rejecting hypothesis H1b and confirming H1a). Our analysis also shows that institutional features, such as how the chief executive is selected (hypothesis H2) and how leaders initially entered their role (i.e., by appointment or election) (hypothesis H3), have roughly the same effects for women and men. The results thus correspond to much of the recent research on reelection at lower levels of elective offices, and suggest that the factors limiting women’s initial access to office have less effect when it comes to securing another term.

Up to this point, we have focused on gender and reelection, but a glance at our Heckman analyses reveals that women leaders run somewhat more than men do (Figures 2a–2f). Unfortunately, the data that would be required to explain the difference, such as interviews or surveys on leaders’ motivations, and specifics about opportunities for other high-prestige jobs, are not available for most of the countries and years in our study. But previous research on gender and electoral politics does offer some clues. For example, Magalhaes and Pereira (Reference Magalhaes and Pereira2024, 1095) used a survey experiment to determine risk preferences among candidates for Portugal’s national parliament. Women running for office proved to be more risk-accepting than men, leading the authors to conclude that “risk-prone women [are] systematically more likely to seek public office.” (See also, Chaudoin, Hummel, and Park Reference Chaudoin, Hummel and Park2024.)

Another possibility is that female and male politicians may have different motives for holding office. Lawless and Theriault’s (Reference Lawless and Theriault2005) study of departures from the U.S. Congress suggested, for example, that women representatives were motivated more than their male colleagues by concern over their ability to influence policy. If the opportunity to do so became blocked, they left office. Men appeared to be motivated as much or more by other rewards of political careers, such as status, and continued to run for office.

A third possibility is that women might run at higher rates than men because they have fewer opportunities to obtain other high-ranking posts once they leave office. Beckwith (Reference Beckwith2015, 728), in her study of gender and party leadership, suggested that strategic senior women understand that their future prospects for high office may be limited. They might thus be more likely to seize the opportunity to run when it’s within reach. Beckwith (Reference Beckwith, Muller and Tommel2022) has noted, for instance, that one of the major post-tenure career paths for former leaders in EU member countries is to hold high office in the EU Commission, Council, or Parliament (see also Alayrac et al. Reference Alayrac, Connolly, Hartlapp and Kassim2025). But very few female leaders have held any of those posts despite the organization’s formal promise of gender equality. Research on post-tenure careers for cabinet members (Claveria and Verge Reference Claveria and Verge2015) and MPs (Claessen, Bailer, and Zwinkels Reference Claessen, Bailer and Zwinkels2021) across Europe has also shown that women are less likely than men to move on to high-status posts in politics or business.

Robustness Checks

We conducted multiple robustness tests to check the consistency of our findings; all lend support to our conclusions about the connections between gender and reelection. One set of tests addressed the issue of sample selection bias, since the results in our analyses could be affected by an imbalance in key covariates between female and male leaders. We employed propensity score matching to reduce the imbalance (see Appendix B).Footnote 16 The results show that even when female leaders are compared with their closest male matches, they still have about the same odds of winning a new term (see the average treatment effect on the treated, ATET).

We also tested for the effect of gender using kernel matching (see Appendix C). While propensity score analysis identifies the members in the control group (men) who are most comparable to the treated (women), kernel matching assigns weights to all control group members and so utilizes all available data. Kernel matching also yields better balance across covariates. These results (see the ATET) offer additional support to our conclusion that women win at about the same rate as men.

Additional tests examined the effects of several other covariates that might alter our findings. We explored whether women leaders might need to be more accomplished to gain the same result as men, as theorizing about the “Jackie and Jill Robinson effect” would predict. To test that possibility, we compared male and female leaders’ previous experiences in high national government posts. While it was not possible to get an accurate count of all national offices they held and the amount of time they served in each one, we did gather data on whether they had occupied any such posts: former president, prime minister, speaker or president of parliament, leader of the opposition, or cabinet official; or the first deputies for these offices. On average, female and male leaders had similar types of prior experience in these offices. For instance, four-fifths had served in the legislature (82.6% of female leaders, and 80.6% of males). Nearly four-fifths of the women (78.3%) and about two-thirds of the men (65.5%) had held at least one cabinet post. Altogether, counting the types of high offices leaders held, previous experience in such posts has about the same effect on reelection for both women and men (Appendix D).

We also considered whether women’s odds of gaining a new term depend on the power of the office they hold. They might manage to win posts that carry less influence than those held by men. We explored the issue by including a measure of the concentration of power in the chief executive’s office, from V-Dem. The results, in Appendix D, suggest that concentration of power does not necessarily improve the odds of winning a new term. When we include it in the model, women and men still have about the same chances of reelection.

Another question is whether women leaders’ odds of reelection might be higher if the country had a previous female chief executive. To answer it, we estimated a Heckman selection model with a covariate for prior female leader and interacted it with whether the president/PM was female. The analysis in Appendix D suggests that having had a previous female leader does generate a modest increase in women presidents/PMs’ chances of winning (p < .10). And the graph of the interaction term in Appendix D bears it out.

An additional test examined whether women leaders’ prospects for a new term might be better in more developed economies. We added a measure of GDP per capita (logged) and interacted it with whether the president/PM was female. As the graph of the interaction term suggests, women have tended to fare better in more developed economic contexts (Appendix D).

We also examined the impact of dynastic politics, given that women have been more likely to reach the highest office after a male relative has held it. However, having such a family tie makes no difference for either female or male leaders’ reelection (Appendix D).

Further analysis explored another issue. Some eligible leaders seeking a new term might be out of office for various reasons. For example, they might be required to step down during the campaign, and so would not be in office on election day. Some eligible prime ministers may resign in order to trigger an election, in hopes of winning more seats. They, too, might not be in office on the day of the election. Identifying the reasons for departures is thus a challenge; the reasons for these and other departures cannot always be identified clearly, given the span of countries (98) and years (1960–2023) in our timeframe.

The question is whether the results might differ if we focus only on the presidents/PMs who were in office when the votes were cast. There are 504 such leaders, and the analyses are included in Appendix E. Propensity score and kernel matching results (Appendix E) bear out the conclusion that women and men presidents/PMs have roughly the same odds of winning a new term. And the results for Heckman models are very similar to the ones presented in Figures 2 and 3. Women fare about as well as men do in winning a new term. On average, leaders chosen via direct election and those with a higher share of the previous legislative vote have higher odds of reelection. Leaders also fare better when the economy is growing, and levels of corruption and domestic conflict are low.

When we examine interaction terms for female leaders, the results reveal that women and men have about the same chances of winning whether they are selected by direct popular election or by appointment, and whether they enter office via election or replacement. Interaction terms for our four performance indicators show the same patterns as in Figure 3. Female and male presidents/PMs win at about the same rate when the economy is growing, and lose at roughly the same rate when executive branch corruption is more extensive. Men’s odds decline when inflation is higher and domestic conflict is more extensive, while women’s do not. As we suggested earlier, these differences might reflect the fact that many women leaders have come to power in countries with less stable political and economic systems.

Conclusions

In this paper, we provide a first cross-national analysis of gender and reelection at the top of the political hierarchy. In contrast to previous studies based on leaders’ time in office, we have focused on whether eligible presidents/PMs win a new term. This eliminates the effects of differing terms in office and provides a more nuanced picture of how gender affects leaders’ prospects in the highest office.

We show that, contrary to arguments emphasizing women’s tenuous hold on high office, eligible female leaders on average are as likely as men to win reelection. We also find that some factors identified as barriers to women’s entry into office have little effect when it comes to winning reelection. Women win about as often as men do whether they compete in a direct election or are appointed to office, and whether they entered the office initially by election or replacement. They also win at about the same rate as male leaders when the economy is growing and when corruption is less extensive. They fare better than their male counterparts in conditions of higher inflation or higher domestic conflict, perhaps because many women leaders have come to office in countries experiencing more turmoil.

Looking at reelection provides both women and men presidents/PMs with a common history; every leader studied here has already had concrete experience gaining access to the highest office. We think this mitigates confounding factors like previous experience, but it also means that we exclude many women (and men) presidents in countries with a one-term term limit, such as those in South Korea, the Philippines, and parts of Latin America.Footnote 17 We want to be clear that our results apply to reelection, and not to initial entry into the highest office.

Our results suggest that there may thus be two very different processes at work in determining the presence of women in the highest office. What helps them win a new term is not necessarily the same as what helps them access the office in the first place. While much of the previous literature finds significant barriers that limit women’s access to the top political role, our data show that for women holding these offices, several of those barriers have little impact on winning reelection. This suggests that many of the obstacles to women serving as prime ministers or presidents occur during the initial process of entering office. Once in office, women face a more even playing field when seeking reelection.

These findings have important implications for groups and organizations advocating greater representation of women in the posts of president and prime minister. Overall, efforts to expand their presence in these offices should focus on the starting points—facilitating initial entry into office (cf. Bernhard and de Benedictis-Kessner Reference Bernhard and de Benefidtis-Kessner2021) and expanding the pools of lower offices that serve as recruiting grounds.

Finally, we hope that our research inspires additional large-scale comparative studies of women leaders. There is much work to be done. For example, most of what we know about what motivates women to run for office, and how their post-tenure career paths compare to those for men, comes from studies conducted in the U.S. and Europe, and only for short spans of years. We believe that more cross-national comparative studies are required to truly understand gender’s effects on access to, and reelection in, the highest political office.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X26100609.

Acknowledgments

Previous versions of this paper were presented at the Midwest Political Science Association Annual Meeting in Chicago, April 2024, and the European Conference on Politics and Gender at Ghent University, July 2024. This version has been updated to include data that were not available earlier. We would like to thank Bumba Mukherjee for his statistical expertise and advice, as well as Lindsay Walsh and Rachel Yeung, for their help in collecting the data. We thank Karen Beckwith, Mona Lena Krook, Young Hun Kim, and three anonymous reviewers for their detailed comments on earlier drafts. We are grateful to Penn State’s College of the Liberal Arts for research support. We also want to acknowledge Susan Welch, who was part of our research team but passed away too early to collaborate on this paper. We miss her and are thankful for her early input. None of these people is responsible for the errors and omissions that inevitably remain here.