Introduction

Over the past few decades, employment risk has undergone a structural shift, with responsibility increasingly shifting from governments and employers to individual citizens and employees (OECD, 2019). Contemporary labour practices generally reflect a reduced sense of employer responsibility for employee well-being, resulting in lower job security, increased long-term unemployment, underemployment, and unstable work conditions (Schmid and Wagner, Reference Schmid and Wagner2017). This insecurity mainly affects unemployed individuals, who must navigate precarity largely on their own (Kalleberg, Reference Kalleberg2011). Although periods of recovery have occurred, improvements have been unevenly distributed, negatively affecting the most vulnerable and contributing to labour market polarisation (OECD, 2019). Meanwhile, cuts to the welfare state globally have intensified pressures on the most vulnerable populations (Greer and Symon, Reference Greer and Symon2014). As ideologies emphasising meritocracy and individual responsibility gain prominence, society at large tends to blame individuals rather than the system, overshadowing structural inequalities and sidelining political solutions to these problems (Swiersta and Tonkens, Reference Swierstra and Tonkens2006; Clarke, Reference Clarke2013; Eriksson and Eriksson, Reference Eriksson and Eriksson2023). The emphasis on meritocracy, promoting self-reliance and active participation, has also contributed to negative perceptions of those in lower social economic positions (Simons et al., Reference Simons, Houkes, Koster, Groffen and Bosma2018). This tendency fuels anti-welfare attitudes and a divisive ‘them versus us’ narrative in public, political, and media discourses (Jensen, Reference Jensen2014; Hudson et al., Reference Hudson, Patrick and Wincup2016; McArther and Reeves, Reference McArthur and Reeves2019). In this macro-level context, stigma functions as a tool for institutions to influence individual behaviour (Tyler and Slater, Reference Tyler and Slater2018). For example, it encourages people to adapt positively to adversity, particularly by re-entering employment instead of relying on welfare. Such perspectives often minimise structural causes, making welfare recipients feel personally responsible for their unemployment.

Within this framework, welfare stigma is a central factor shaping the lived experiences of welfare recipients. A substantial body of scholarship have explored various dimensions of welfare stigma, including the stigma associated to claiming benefits (e.g., Baumberg, Reference Baumberg2016), the reluctance to participate in welfare programmes (Simonse et al., Reference Simonse, Vanderveen, van Dillen, Van Dijk and van Dijk2023), and the resulting non-take-up of public provisions (e.g., Friedrichsen et al., Reference Friedrichsen, König and Schmacker2018; Boost et al., Reference Boost, Raeymaeckers, Hermans and Elloukmani2021; Janssens and Van Mechelen, Reference Janssens and Van Mechelen2022). As the longstanding question of welfare deservingness – ‘Who should receive what, and why?’ – remains prominent across European contexts (Van Oorschot and Roosma, Reference Van Oorschot, Roosma, Van Oorschot, Roosma, Meuleman and Reeskens2017), research has highlighted the stigma-driven distinctions between the deserving, or ‘real unemployed’, and undeserving welfare recipients, often labelled as ‘scroungers’ (Boland et al., Reference Boland, Doyle and Griffin2022; Bolton et al., Reference Bolton, Whelan and Dukelow2022). By contrast, research focusing on the lived experiences of individuals who are dependent on welfare remains relatively scarce. While such studies do exist, many are either outdated or highly context-specific, for example those conducted in China (Li and Walker, Reference Li and Walker2018), or within liberal welfare regimes like the UK (e.g., Spicker, Reference Spicker2011). Given that public attitudes towards welfare are closely tied to regime-specific values (Laenen et al., Reference Laenen, Rossetti and Van Oorschot2019; Taylor-Gooby et al., Reference Taylor-Gooby, Hvinden, Mau, Leruth, Schoyen and Gyory2019), this study contributes to the literature by studying individual experiences of welfare stigma within the Dutch welfare context.

The present study specifically explores how long-term social assistance recipients (SARs) in the Netherlands experience and respond to welfare stigma. This focus is crucial given the increasing prevalence of conditionality in social assistance schemes in many countries, including the Netherlands (e.g., Brink and Vonk, Reference Brink and Vonk2020). Such conditionality is not only reflected in policy measures, such as stricter eligibility criteria, mandatory volunteering, and enhanced monitoring of job-search activities, but in shifting public perceptions as well (Veldheer et al., Reference Veldheer, Jonker, Noije and Vrooman2012). In the Dutch context, there is a growing tendency to judge who ‘deserves’ support based on notions of control and reciprocity (Reeskens and Van der Meer, Reference Reeskens and Van der Meer2019), which also influences recipients’ ideas and feelings about each other (Sebrechts and Kampen, Reference Sebrechts and Kampen2022). Against this backdrop, investigating the lived experiences of welfare stigma in the Netherlands is both timely and essential.

Previous research indicates that long-term welfare recipients differ qualitatively from short-term recipients, as they encounter a wider range of obstacles and more complex challenges (e.g., McGann et al., Reference McGann, Danneris and O’Sullivan2019; Franzen and Bahr, Reference Franzen and Bahr2024). In addition, while short-term recipients often view their situation as temporary, they may be less affected by stigma, whereas long-term recipients experience more persistent labelling and identity effects. Therefore, this article focuses on long-term SARs. Our research question is: How do long-term social assistance recipients in the Netherlands experience, and respond to, stigmatisation related to their welfare recipiency?

Experiences and responses to welfare stigma

This article defines welfare stigma as the experiences of social disapproval, shame, and embarrassment that result from receiving welfare (Yaniv, Reference Yaniv1997). Stigma results from the process of stigmatisation, which occurs when a personal attribute, such as being a welfare recipient, is perceived as different within social interactions and leads to a devaluation of that individual’s identity (Goffman, Reference Goffman1963; Dovidio et al., Reference Dovidio, Major, Crocker, Heatherton, Kleck, Hebl and Hull2000; Bos et al., Reference Bos, Pryor, Reeder and Stutterheim2013). As such, stigma functions as a stressor that threatens social identity (Miller and Kaiser, Reference Miller and Kaiser2001). This threat can be triggered by subtle cues present in various media, the workplace, and social settings, and is often overlooked by members of privileged groups (Steele et al., Reference Steele, Spencer and Aronson2002). Welfare recipients are frequently stigmatised, being seen as unproductive, lazy, or unmotivated (e.g., McCoy and Major, Reference McCoy and Major2007; Lott, Reference Lott2012). Studies highlight the multifaceted psychological effects of welfare stigma, including feelings of shame, isolation, diminished self-worth, blame, and condescension (e.g., Collins, Reference Collins2005; Underlid, Reference Underlid2007; Tyler, Reference Tyler2020).

The literature differentiates between perceived and internalised stigma. Perceived stigmatisation refers to the personal experience of being devalued or judged negatively by others (Bos et al., Reference Bos, Pryor, Reeder and Stutterheim2013), and has been linked to significant negative effects on physical and mental health. Reported consequences include poor self-rated health, negative emotions, feelings of inferiority, lack of self-respect, and negative self-perceptions (Rainwater, Reference Rainwater1982; Mickelson and Williams, Reference Mickelson and Williams2008; Pascoe and Smart Richman, Reference Pascoe and Smart Richman2009). When stigma is internalised, individuals adopt these stigmatising labels and come to see themselves through the lens of social devaluation, which fosters shame (Scheff, Reference Scheff2014). Shame, conceptualised as a self-focused negative emotion, further shapes both self-perception and the belief that others view them in a devaluing way (Tangney et al., Reference Tangney, Stuewig and Hafez2011). It can damage one’s identity, fostering feelings of worthlessness, inferiority, and incompetence (Wong and Tsai, Reference Wong and Tsai2007; Kampen et al., Reference Kampen, Elshout and Tonkens2013), which may lead to negative coping strategies such as dissociation, self-oriented distress, anger, mental health issues, and social withdrawal (Tangney et al., Reference Tangney, Stuewig and Hafez2011; Roelen, Reference Roelen2017, Reference Roelen2020). Stigma can also lead to humiliation (Van der Zwaard, Reference van der Zwaard2021), exclusion (Trommel, Reference Trommel2018), and marginalisation (Van Delden, Reference Van Delden2019) for not meeting societal norms. In short, stigma can thus have numerous negative side effects, although individuals may respond differently to the shame and stress associated with being stigmatised.

Recently, García-Lorenzo and colleagues (Reference Garcia-Lorenzo, Sell-Trujillo and Donnelly2022) introduced five different ways individuals respond to welfare stigmatisation, drawing in part from Lister’s (2015) typology of agency. These responses are: getting stuck, getting by, getting out, getting back at, and getting organised. Individuals who ‘get stuck’ tend to internalise stigma, view themselves as a burden or worthless, and withdraw or socially exclude themselves as non-contributing members of society. Those who ‘get by’ struggle to cope with stigmatisation but show resilience as they work towards achieving a positive social position. This involves adjusting their expectations and priorities, modifying lifestyles, staying busy, being resourceful, and sometimes concealing or reframing their stigma. Individuals who ‘get out’ work on overcoming stigma by conforming to societal expectations, securing a (sometimes precarious) job, even if it involves low wages or emigration. Alternatively, some redefine or de-centre employment as their main identity marker (García-Lorenzo et al., Reference Garcia-Lorenzo, Sell-Trujillo and Donnelly2022). While those who manage to ‘get by’ and ‘get out’ acknowledge the stigma, they do not actively resist or challenge it; instead, they accept it as a given and attempt to manage through self-regulation (Creed et al., Reference Creed, Hudson, Okhuysen and Smith-Crowe2014), either by concealing the stigma (‘getting by’) or leaving it behind (‘getting out’). Conversely, those who ‘get back at’ reject welfare stigma and engage in covert resistance, resisting, or negotiating stigmatisation and the resulting shame. Such resistance, also known as ‘weapons of the weak’ (Scott, Reference Scott1985), include practices such as working in the black economy, cheating the government, or engaging in illegal activities (García-Lorenzo et al., Reference Garcia-Lorenzo, Sell-Trujillo and Donnelly2022). Lastly, those who ‘get organised’ reframe stigma as a societal failure rather than an individual one. Through strong group identity feelings, they openly resist and develop an oppositional culture to counter dominant perspectives and negative social constructs (García-Lorenzo et al., Reference Garcia-Lorenzo, Sell-Trujillo and Donnelly2022). These latter two groups demonstrate ‘stigma resistance’, involving actions that challenge existing power structures (Link and Phelan, Reference Link and Phelan2001; Baaz et al., Reference Baaz, Heikkinen and Lilja2017; Tyler, Reference Tyler2020).

Conceptual model

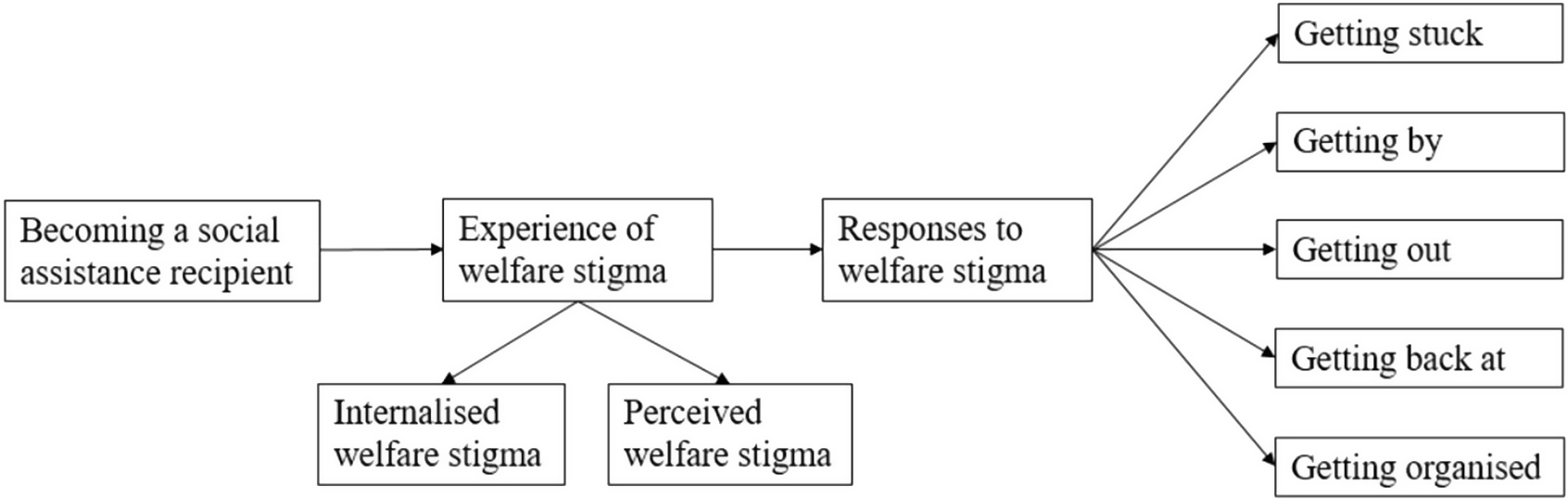

A conceptual model was employed to guide the research. As outlined in Figure 1, this model delineates the key concept and integrates insights derived from both psychological and sociological research. We anticipate that SARs experience welfare stigma, either perceived, internalised, or both, based on the existing literature. Furthermore, we applied the five distinct responses to welfare stigmatisation, as identified by García-Lorenzo and colleagues (Reference Garcia-Lorenzo, Sell-Trujillo and Donnelly2022), as deductive codes within our model.

Figure 1. Conceptual model on experiences of, and responses to, welfare stigma.

Research methods

We conducted individual in-depth interviews to explore the experiences with stigma among long-term SARs and their coping strategies. These semi-structured interviews, which featured open-ended questions, took place in the Northeastern region of the Netherlands. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Sociology Department of the University of Groningen (ECS-200824). Before the main interviews, we held preparatory meetings with key informants, including work coaches and social workers, conducted two pilot interviews and refined the interview guidelines regarding language and vocabulary.

Participants were selected based on specific inclusion criteria (Bryman, 2016): (1) having received social assistance benefits for over two years; (2) residing in one of two selected municipalities, and (3) aged between twenty-seven and sixty-seven. To ensure diversity, we employed three recruitment strategies (McKenzie et al., Reference McKenzie, Neiger and Thackeray2022): the municipal benefit agency distributed flyers to home addresses of long-term SARs, the key informants conducted personal outreach to their clients, and finally, we used the snowball sampling technique. Although contacting long-term SARs directly at their home addresses could be seen as potentially intrusive, we sought to minimise this and power imbalances by clearly emphasising that participation was voluntary and anonymous, and that interview content would not be shared with the agency.

Thirty-five people initially expressed interest in participating in an interview. Two potential participants were excluded, and four dropped out, resulting in a final sample of twenty-nine participants. Each participant received an information letter via email and provided informed consent, either electronically or on paper.

The ages of the participants ranged from thirty-two to sixty-five years (M = fifty-one). There were more male (62 per cent) than female (38 per cent) participants, which differs from national statistics indicating that 57 per cent of Dutch SARs are female (CBS, 2023). Twenty-two identified as Dutch, while seven participants had diverse ethnic backgrounds, including British, Indonesian, Ukrainian, and Somali. Most participants lived alone, while only a few shared their household with children, a partner and children, or with someone in a mutual caregiving setup. Only two participants held an applied higher education degree; most completed secondary vocational education or secondary school. On average, participants began receiving social assistance benefits at age forty. Most received benefits for between two and ten years, with seven and four participants receiving benefits for over ten and twenty years, respectively. The majority of participants reported severe physical and mental health issues, whereas only five participants did not mention health-related issues as a cause of their welfare dependency.

The interviews took place between February and June 2021. Participants could choose between in-person or video call formats to promote inclusivity and broad participation. Fifteen interviews were held at participants’ homes, seven in private rooms at welfare organisations or community centres, and seven through video calls. Most participants preferred face-to-face interviews to comfortably share personal experiences, while others opted for video calls to minimise physical interactions due to Covid-19 concerns. Before the interview, the researcher and participant took time to get acquainted by sharing personal information with each other, aiming to build trust and openness. Each interview began with questions about daily routines and social networks, gradually moving towards more sensitive topics such as personal experiences and feelings related to welfare. The complete interview guideline is available upon request. After each interview, participants received a €10 gift card as a token of appreciation. The interviews lasted between 24 and 121 minutes (M = sixty-four), were conducted in Dutch, and recorded and transcribed verbatim, with potential identifiers removed. The first author translated the quotes, and all names were replaced with pseudonyms. Fieldnotes were taken throughout the research to reflect on the researchers’ positionality.

Data were analysed in ATLAS.ti version 23. A thematic analysis was employed to explore patterns of stigma experiences and responses. Its flexibility in analysis, orientation, and perspective supported the study’s experiential and exploratory nature (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006). We followed Braun and Clarke’s (Reference Braun and Clarke2006) six-step process: initially familiarising ourselves with the data (step one), after which we initiated the coding process (step two). We used a hybrid approach of analysis that balanced an open perspective with theoretical grounding. We began with inductive, data-driven coding to explore participants’ experiences of welfare stigma, and subsequently applied deductive codes to systematically align these findings with the constructs delineated in the conceptual model. After coding all relevant data, we started dividing codes into (sub)themes (step three). The themes were refined through the review and consolidation of data extracts (step four), followed by defining the core meaning of each theme (step five). Finally, we integrated insights from both inductive and deductive coding to report our findings (step six).

Results

Welfare stigma experiences

When our participants ended up on welfare, many of them experienced both perceived and internalised welfare stigma, along with its negative consequences. They experienced perceived stigma across diverse contexts, including the media, politics, institutions, and society as a whole. Marije, who has spoken twice at the City Council to advocate for welfare recipients, shared her personal experiences with stigma in the political arena:

And then someone from [political party] said: ‘yeah, on welfare… they are all just really just people who…’ – Well, anyway, it basically came down to the fact that people on welfare, they are just there because of their… it is actually their own fault, and they just do not want to get out of it.

Many participants have faced similar experiences, as Nimo explained:

People look at you differently when you are on welfare. (…) Even at the welfare institution. (…) I have had to feel that a few times, I do not like it. (…) People who think: ‘well, well, you are eating our tax money’.

Participants often feel stigmatised not only by those who are more distant, but also by people close to them. As Herman told us: “And even my brother, for instance, views me as someone with a begging hand.” Consequently, family bonds or friendships sometimes weaken or get destroyed. As Guus said: “A friend of mine, whom I have known for years, hears about the situation [that I receive social assistance] (…) and eventually that friendship is over.”

Surrounded by negative stereotypes, participants often came to internalise welfare stigma. Anna described her negative self-image when applying for social assistance: ‘It was very difficult [to start receiving welfare]. (…) I found it terrible, really terrible. Because I felt… I thought: “now I am becoming one of those dirty benefit scroungers, that is not possible, is it?”’

As they internalised welfare stigma, they felt ashamed and guilty. As Nimo explained: ‘Sometimes when people are lumped into a group of “that kind of [welfare] person” – yes, then you become one of them too. Then you start feeling that way, too. (…). In the beginning, out of shame (…) I did isolate myself (…) with shame for poverty, shame for being a failure.’

As the latter example illustrates, feelings of shame and guilt often stem from a sense of inadequacy and the inability to earn a living. Willow told us: ‘The way I am living, most of the time I feel guilty, that I am not out there making my own money. I am costing the system money now’. Since they are no longer employed, they tend to form a negative perception of themselves, as they no longer meet their own standards. As Max illustrated: ‘It is, certainly, a shame that (…) everyone else who lives in the street is working and you are just living there aimlessly… (…) I felt ashamed that I no longer met the standards I had set for myself’. Although participants refer to these standards as personal, they are often influenced by the dominant meritocratic values in society.

We found that many participants have negative stereotypical views of other welfare recipients. As Herman recounted: ‘But I myself also had the prejudice about people receiving benefits. (…) I had the idea of people just killing time all day on the couch, with a yawning dog, smoking, and all of that’. Often, this negative image of recipients can lead to internalised stigma, making it even more difficult to be a SAR, as Varun explained:

I have always been one of those people who focus on work, and also someone who had a negative image of people on welfare, that they are lazy and so on. (…) So, at a certain point it becomes very difficult to accept that you are on social assistance. You constantly feel guilty (…) and you do not allow yourself anything.

In summary, our participants frequently faced both perceived and internalised stigma, which impacted their social relationships and contributed to feelings of shame and guilt. Overall, the experiences related to perceived and internalised stigma were fairly similar among our participants.

From getting stuck to acceptance

The experience of becoming a SAR, coupled with the associated welfare stigma, often led participants to withdraw socially and adopt harmful behaviours, including alcohol abuse, unhealthy lifestyle, or self-neglect. As Tim illustrated: ‘I have a lot of neglect in my house as well (…) I can no longer find my peace (…) I sleep very poorly and the food I eat, it is maybe once every few weeks that I have a hot meal and the rest is all, well, sometimes fries or chocolate or chips’.

Likewise, Nimo explained: ‘In the beginning, out of shame and the change of my situation, I isolated myself, like: I do not want to see anyone. (…) The shame of poverty, (…) the breakup, and not wanting to admit that I had failed’. These behaviours align with the findings of García-Lorenzo and colleagues’ (Reference Garcia-Lorenzo, Sell-Trujillo and Donnelly2022) on ‘getting stuck’: individuals felt overwhelmed by their circumstances, internalised the stigma, pulled back from social interactions, and became ‘invisible’. After a period of ‘getting stuck’, our participants began to see and experience being a welfare recipient in a new light, leading to a change in their responses. In some way, they managed to come to terms with their situation. As Teun explained: ‘I accept it now. (…) I know that I struggle with doing it this way, with holding out my hand because I do receive money. (…) But the situation calls for it, that I need it [social assistance] for a little while, so I accept it’.

Varun, who suffered two heart attacks following his discharge from fulltime employment, had a similar experience: ‘It also involves acknowledging that you are vulnerable, and that you might not achieve the level of work or status you aspire to. (…) Accepting that you have experienced significant challenges’. Through their experiences, not only did their negative self-perception change, but also their view of other welfare recipients. As Anna explained:

You do start looking at things very differently because yes, who knows what story lies behind those people [on welfare]. If you see why I ended up on welfare; I have had so much to deal with. (…) Who knows what they have had to deal with before they ended up there. Maybe I have been judging way too harshly all this time.

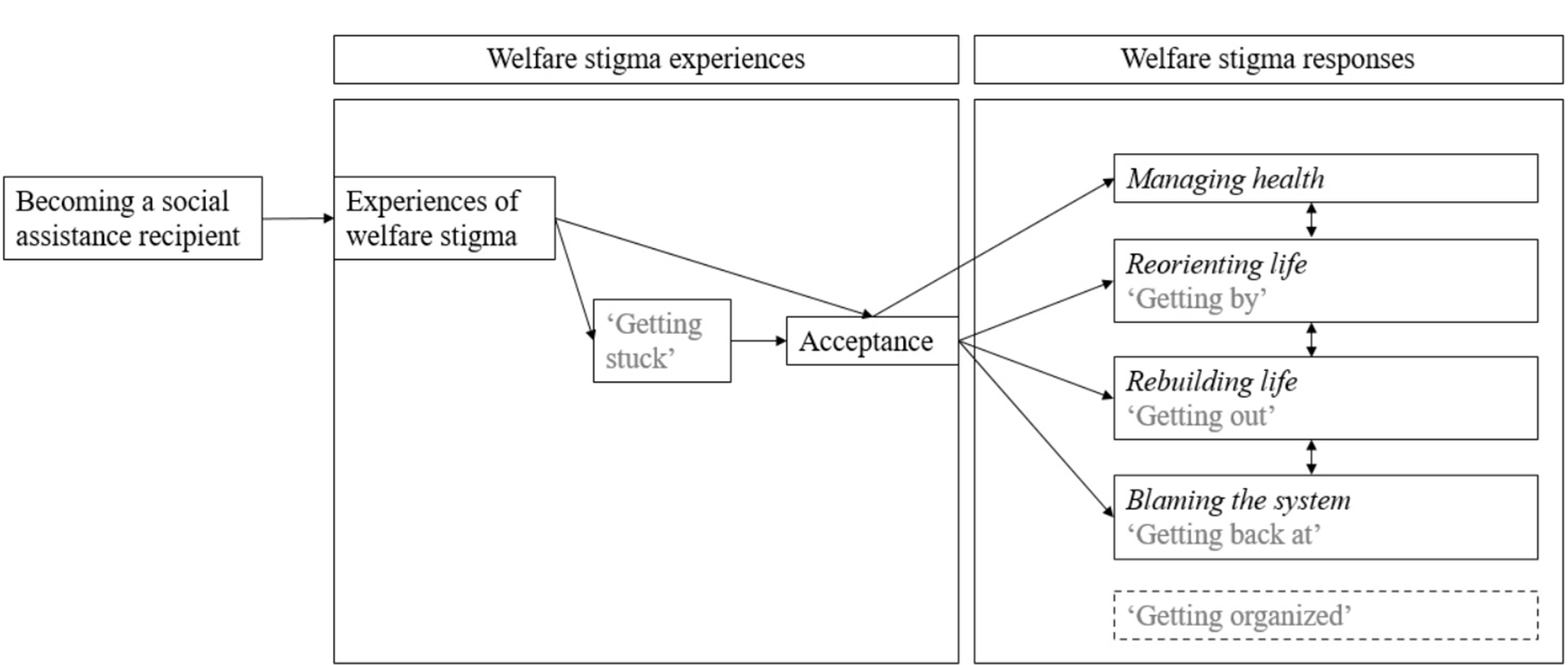

Following these processes, we identified three distinct groups in our data: those who are currently reorienting life, rebuilding life, or blaming the system. Another group, managing health, did not experience the initial phase of ‘getting stuck’ like the others. For instance, Saskia, who had lived with fibromyalgia for years, said that coming to terms with her reliance on benefits was relatively straightforward once her physical condition had worsened to the point where she could no longer work.

Responses to welfare stigmatisation

Although some behaviours or beliefs may be shared between groups, we grouped individuals by the most common and defining ways they responded to stigmatisation. We found four distinct groups, each representing different reactions to the stigmatisation of welfare. Individuals may shift between groups as their personal circumstances and behaviours change, although this is not examined in depth in this article.

Managing health

This group includes four individuals who face significant physical and mental challenges, such as fibromyalgia, PTSD, anxiety, or depression. Some reside in supported living facilities, while others attend therapy sessions multiple times a week. Their daily difficulties hinder their participation in activities and their pursuit of work or hobbies, as they are often focused on managing their own wellbeing. As Boris illustrated: ‘The most important thing for me is my depression, and yes, that is why I cannot do many things anymore. (…) I cannot work, and I do not have any hobbies anymore. It costs me too much energy’. This group appears less vocal about negative experiences with welfare stigma than the other three, likely because managing their health demands all their energy.

Their self-perception is primarily shaped by their health conditions and the daily challenges they face, rather than identifying themselves as welfare recipients burdened with the stigma of laziness, lack of motivation, or failure. As Zoë explained: ‘It [the failed job attempts] happened to me rather than being my own fault (…) I have never felt a warm welcome by employers, which was quite painful to experience (…) but now I know that is all due to my PTSD [complaints], and that gives some peace’. Their medical condition supports the belief that they are unable, rather than unwilling, to work, which enables them to deflect shame and responsibility for their circumstances. In addition to the stigma associated with welfare, they experience a broader sense of shame and stigma in various aspects of life, feeling that their lives are significantly different from those of others. As Boris, who is battling depression, told us: ‘I have suffered a lot from shame (…) That I did not have a job, that I lived with my father until I was twenty-nine. I did not have a girlfriend. Everything that is normal that you should have, I did not have’.

Moreover, individuals in this group sometimes lack a sense of meaning in their daily lives. Zoë, who suffers from PTSD, described: ‘I struggle with not being able to contribute much to that [society], and feeling like disconnected from the flow of everyday life (…) what I miss most is having a purpose in life that involves daily or weekly engagement, where I can actively participate in society’.

It shows that in our society, being valuable is often linked to being productive within capitalist system, a perspective that reinforces welfare stigma.

As some participants aged, their feelings of shame lessened, even though their symptoms continued to significantly impact their daily functioning. This often resulted from accepting that their lives had taken a different path than initially expected, and in some cases, they cultivated an optimistic attitude despite the hardship they faced. In Herman’s words:

In the past… (…) I had an idea of how life was going to be. Expectations… and the stupid thing is, they are often expectations that have been deeply ingrained by society… And if you do not meet them, you are seen as different by others. And that is something that I have found very difficult, but now I am starting to appreciate it more and more. Because it also has very good sides.

In summary, members of this group experience stigmatisation not only for receiving welfare but also for not fulfilling other societal expectations. However, given that their diagnosis demonstrates an inability to work rather than reluctance to do so, they frequently come to terms with their circumstances by attributing responsibility to external factors. Moreover, managing their health issues often demands so much energy that it leaves insufficient capacity to concern themselves with, or to actively resist, the associated stigma.

Reorienting life

Similar to those ‘getting by’ (García-Lorenzo et al., Reference Garcia-Lorenzo, Sell-Trujillo and Donnelly2022), thirteen of our participants worked towards achieving a positive social position after adjusting their expectations and priorities following their transition to welfare. As Frank explained: ‘I felt like: if I cannot do anything myself [becoming employed], then maybe I can help other people. And that [helping others] gives you back your self-respect, and that is all that matters’. However, unlike those ‘getting by’, our findings suggested that participants did not need to have paid employment to make a meaningful contribution to society. Instead, we found that after a tough period of feeling ‘stuck’, individuals had found their way and were fairly content with their sense of identity and role in society. Some of our participants, such as Henk, considered paid work and volunteering to be comparable: ‘Earlier, when I was working, I got a lot of satisfaction from my job (…). When I helped people, they were happy and satisfied again (…) – and I still feel the same now [as a volunteer] (…). Basically, not much has changed, except for the salary’.

Many of these individuals volunteer regularly, with some doing so daily (up to five days a week) and others weekly. They recognise the value of their volunteer efforts, seeing them as beneficial both for themselves and for others. For instance, Willow mentioned: ‘I have been realising myself that the volunteer work also has its own value, especially when I focus, think, and speak to the right people and am part of the community network’. They take each day as it comes, prioritising volunteer work, household chores, and informal caregiving, while not actively seeking paid employment due to health issues or caregiving duties. For example, Dian, who previously worked in factories and as a cleaner, was deemed unfit for work after being diagnosed with carpal tunnel syndrome. Currently, she spends her time caring for her daughter, serving coffee in a nursing home, preparing food for the market, managing her household, and pursuing her hobbies. Overall, after a period of getting stuck, they challenge the stigmatising norm of paid employment by redirecting their lives towards activities they find meaningful for themselves and others.

Rebuilding life

Eight of our participants take personal responsibility for regaining their position an aim to reintegrate into the system, similar to those who are ‘getting out’ (García-Lorenzo et al., Reference Garcia-Lorenzo, Sell-Trujillo and Donnelly2022). These participants cope with stigma by temporarily redefining or downplaying employment as their primary identity marker. Instead of identifying as unemployed or a welfare recipient, they temporarily view themselves as volunteers, students, or individuals gaining work experience or focusing on their health. Their ultimate aim is to secure long-term paid employment, prioritising the societal ideal of paid work more than the reorienting life group and showing less resistance to stigma. Unlike the findings of García-Lorenzo and colleagues (Reference Garcia-Lorenzo, Sell-Trujillo and Donnelly2022), our participants did not accept precarious jobs that required them to leave the country to work.

Individuals in this group are less content with their current situation as compared to those in the reorienting life group, because they believe they can achieve more in their lives than they currently are. As Teun said: “At the volunteer work, I am starting to realise: I can do more than this (…) I am ready for something else, a new challenge.” Therefore, after a difficult period with, for example, health issues, bankruptcy, and/or divorce, they are now in the process of rebuilding. This involves working on their health, pursuing studies, engaging in volunteer work, attending therapy, applying for paid employment, or usually a combination of these activities. For example, Sarah is juggling multiple responsibilities: writing a business plan, caring for a young baby, supporting her mother, helping her husband learn Dutch, and managing her health after several traumatic events.

Overall, participants in this group are highly motivated to pursue paid work, and they address stigma by temporarily redefining or downplaying employment as their primary identity.

Blaming the system

Four participants blame the system and exhibit similarities to those ‘getting back at’ (García-Lorenzo et al., Reference Garcia-Lorenzo, Sell-Trujillo and Donnelly2022) as they reject stigma as a personal failing and express anger towards the social situation. As Lianne explained:

Initially, I ended up on welfare, and when I left [the company], my intention was to get back to work. But, in reality, it did not work that way: I was nearly fifty years old, and there were no employers willing to hire me (…). Moreover, the government has made massive budget cuts, so all the work I could potentially do has been eliminated: it has all turned into volunteer work.

Similarly, Siem told us: “I cannot imagine that in those ten years (…) there was never a place for me at the [company] (…). And yes, there must be a reason for it, but I have wondered why so many people are sitting at home.” Later, Siem explained that, based on his experience, social services often prevented people from accepting volunteer roles because they needed to remain available for paid jobs as they became available, although many had already waited over three years for such positions. Lianne and Siem’s statements demonstrate their strong awareness of being marginalised by ‘the powerful’, such as the government and institutions.

Unlike the ‘getting back at’ group, individuals do not engage in ‘weapons of the weak’ behaviours such as working in the black economy or cheating on taxes. Instead, they dedicate much of their time to supporting vulnerable individuals, for instance, by assisting with household and garden chores for those with limited financial means, or drawing on their own experiences of poverty to serve as mentors or buddies. They engage in various activities, including volunteering in multiple settings or providing informal care to parents, children, or acquaintances. Members of this group tend to have broader social networks and fewer health issues than the others. They are motivated by a strong desire to contribute to society, although external barriers, such as age discrimination and limited flexible employment options, hinder their job prospects. For example, Anna, a thirty-five-year-old single mother to three children aged ten, nine, and five, has applied for multiple jobs but finds them incompatible with her caregiving responsibilities. She has decided to postpone her job search until her youngest child requires less medical attention and is ready to start school.

Participants in this group do not view welfare stigma as a personal failure but instead attribute it to systemic issues such as government policies, budget cuts, age discrimination, or lack of flexible work options.

The fifth and final response to welfare stigmatisation, as outlined by García-Lorenzo and colleagues (Reference Garcia-Lorenzo, Sell-Trujillo and Donnelly2022), is ‘getting organised’ where individuals with a strong sense of group identity aim to reshape interpretations by reframing welfare stigma as a societal failure. However, we did not observe such responses among our participants. One key reason is the prevalence of ‘othering’, mutual stigmatisation, among SARs, which hampers solidarity and collective action (Chase and Walker, Reference Chase and Walker2013; Bratton, Reference Bratton2015; Sebrechts and Kampen, Reference Sebrechts and Kampen2022). Additionally, our recruitment through municipal channels may have limited access to individuals who challenge the system and the government’s role, as those individuals are more likely to be recruited through other networks. Figure 2 provides a summary of our findings.

Figure 2. Results on experiences of, and responses to, welfare stigma.

Conclusion and discussion

This article examined how long-term SARs in the Netherlands experience and respond to welfare stigma. Participants reported encountering stigma in various contexts, including political and institutional settings, as well as within close social circles, such as friends and family. Consistent with Patrick (Reference Patrick2016), our results indicate that participants often internalised stigma when faced with persistent negative stereotypes. After becoming SARs, many initially responded with social withdrawal. They engaged in harmful behaviour such as alcohol abuse, unhealthy lifestyles, or self-neglect, patterns that align with the concept of ‘getting stuck’ as described by García-Lorenzo and colleagues (Reference Garcia-Lorenzo, Sell-Trujillo and Donnelly2022).

After a period of feeling stuck, SARs were able to accept their status as welfare recipients. They addressed welfare stigma by reorienting life, rebuilding life, and blaming the system. Another group, labelled managing health, demonstrated a different trajectory and avoided the ‘getting stuck’ phase. We interpret this as the adoption of a ‘sick role’ (Parsons, Reference Parsons1951), which enabled them to attribute their situation to their illness and deflect welfare stigma. In contrast, individuals of the other three groups experienced a stronger internalised welfare stigma, shaping their responses accordingly.

First, individuals who are reorienting life adjust their expectations and priorities, recognising the value of their current activities such as volunteer work and informal caregiving – both for personal fulfilment and for the benefits they provide to others. In doing so, they attempt to reduce stigma by creating alternative sources of pride and respect (Bourgois, Reference Bourgois2003). Second, those who are rebuilding life align more closely with societal ideals, viewing activities such as gaining work experience, improving health, or pursuing education primarily as steps toward the ultimate goal of paid employment. They take full personal responsibility for reintegration and only temporarily decentralise paid work as their main identity marker. In that way, members from this group do not counteract stigma as strongly as members from the other groups. Last, individuals blaming the system reject the stigma as a personal failing and instead blame powerful entities such as the government, institutions or the labour market, expressing anger at broader social structures. Like the managing health group, they attribute their circumstances as resulting from external factors beyond their control, such as informal caregiving duties or labour market inflexibility. Like the reorienting life group, they opt to engage with meaningful social activities and aim to contribute in the form of caring responsibilities or voluntary work. The four groups can be summarised as: ‘I am not a lazy, unmotivated welfare recipient but… I am ill’ (managing health), ‘I am engaged in other meaningful activities for valid reasons besides paid work’ (reorienting life), ‘I am working on myself to return to work in the future’ (rebuilding life), or ‘I blame the system/others that I am in this situation’ (blaming the system).

These responses indicate that the managing health and blaming the system groups redirect the responsibility for their circumstances, whereas the other groups only deflect the shame. The key difference between the reorienting life and rebuilding life groups is that the reorienting group challenges the stigmatising norm that views paid work as the sole source of pride, whereas the rebuilding group accepts this norm and aspires to achieve it in the future. Although both the managing health and blaming the system groups attribute their circumstances to external factors, our analysis shows that the blaming the system group internalises welfare stigma more deeply because their reasons for welfare use are less visible or socially accepted. This aligns with Scambler’s (Reference Scambler2018) concept of ‘heaping blame on shame’, which suggests that individuals can be stigmatised either ontologically, implying an ‘imperfect being’, or morally, by being blamed for lacking responsibility or a strong work ethic. Participants who are managing health only experience stigma on an ontological level, while those blaming the system may encounter both ontological and moral stigma. Over time, however, the latter group increasingly sees their difficulties as arising from broader social and institutional structures rather than personal failings. Acting as mentors or buddies helps reinforce this perspective by highlighting the structural causes of these issues. This experience further lessens the individualising impact of stigma, framing personal struggles as shared, systemic problems.

Our results support earlier research that emphasises SARs’ resilience in finding diverse ways to overcome challenges and obstacles (e.g., Martilla et al., Reference Marttila, Johansson, Whitehead and Burström2013). They also resonate with studies indicating that recognising the value of caregiving and rejecting blaming narratives are effective strategies for resisting stigma (Evans, Reference Evans2022), as we observed in the reorienting life and blaming the system groups, respectively. Moreover, our findings align with previous research identifying voluntary work as both a source of meaning and a strategy for countering stigma (Jordan, Reference Jordan2022).

Unlike García-Lorenzo and colleagues (Reference Garcia-Lorenzo, Sell-Trujillo and Donnelly2022), we did not observe individuals ‘getting organised’. This discrepancy may stem from differences in study contexts, such as variations in unemployment rates and welfare policies (Sanz-de-Galdeano and Terskaya, Reference Sanz-de-Galdeano and Terskaya2020), as well as differences in sampling methods.

As personal circumstances and behaviours change, individual responses also tend to shift. Therefore, future research may benefit from using a longitudinal design to better capture the development of experiences with stigma and responses to it over time. Additionally, exploring more recent experiences of the ‘getting stuck’ phase would be valuable, as our study only includes retrospective data on this aspect. Reflecting more broadly on our findings, it is worth noting that Walker (Reference Walker2014), in his research on poverty, emphasised that people often unconsciously adopt strategies such as ‘being seen to be coping’ in order to manage the shame associated with their situation. To appear ‘normal’, individuals may present a more positive picture than their actual experiences. This behaviour may be relevant to our research, suggesting that individuals might face greater difficulties in responding to welfare stigma than our study indicates. Additionally, given the context-specific nature of our findings, future research should aim to examine, and ideally compare, the lived experiences with welfare stigma across diverse welfare regimes and socio-cultural contexts.

A limitation of our study is the potential presence of selection bias. We expect that long-term SARs who suffer most from welfare stigma may have been less inclined to participate in interviews as compared to those who are doing relatively better. This could help explain why no participants were in the ‘getting stuck’ phase at the time of the interview. Additionally, individuals with the most negative attitudes towards institutions might also have been less likely to take part.

Welfare stigma, whether perceived or internalised, is widespread among long-term SARs in the Netherlands, often resulting in feelings of shame and guilt. Although welfare recipients themselves actively try to combat this stigma, this study points out how painful and isolating this process can be. Therefore, social interventions are necessary to help SARs develop stigma-resilient identities and engage in meaningful activities suited to their unique needs and circumstances. For example, the self-management of well-being intervention (Steverink, Reference Steverink, Pachana and Laidlaw2014) focuses on individuals’ remaining strengths rather than their limitations. While it does not explicitly target stigmatised identities, the intervention aims to boost self-confidence and foster a sense of purpose in daily life, factors that indirectly reinforce personal identity and social roles. Additionally, benefit agencies can support individuals redefining their identities after losing certain roles, especially those related to work. Emphasising the value of existing roles, such as managing illness, caregiving, or personal growth, rather than spotlighting roles that they may not yet hold, can be a meaningful starting point in this process.

Furthermore, it is crucial for public, political, and media debates to address underlying societal issues such as labour market discrimination and demands. These norms and discourses should also emphasise the value of reproductive and caring work, along with other unpaid activities. To reduce the stigma associated with welfare, the prevailing discourse that welfare is used for personal convenience must shift towards acknowledging that individuals may need, and have the right, to utilise this social safety net, whether for a short or an extended period. Such a shift can help SARs to accept their situation and take steps forward.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their sincere gratitude to the anonymous peer reviewers for their engaged feedback, insightful comments, and valuable suggestions.

Financial support

This work was supported by the ‘Nationaal Programma Groningen’ (no grant number available).

Funding statement

Open access funding provided by University of Groningen.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Author Contributions: CRediT Taxonomy

Amber Vellinga-Dings: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing - original draft.

Nardi Steverink: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing - review & editing.

Başak Bilecen: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing - review & editing.

Melissa Sebrechts: Writing - review & editing.