Introduction

Invasive parasites pose a significant threat to new hosts and ecosystems, often causing elevated mortality and altered disease dynamics in their hosts due to lack of coevolution and mutual adaptation (Burreson et al. (Reference Burreson, Stokes and Friedman2000); Dunn Reference Dunn2009; Poulin Reference Poulin2017; Poulin et al. Reference Poulin, Paterson, Townsend, Tompkins and Kelly2011). Many introductions of marine parasites have caused widespread disease and high mortality in immunologically naïve host populations (Burreson et al. (Reference Burreson, Stokes and Friedman2000); Corbeil Reference Corbeil2020; Friedman et al. Reference Friedman, Andree, Beauchamp, Moore, Robbins, Shields and Hedrick2000; Keeling et al. Reference Keeling, Brosnahan, Williams, Gias, Hannah, Bueno, McDonald and Johnston2014; Whittington et al. Reference Whittington, Crockford, Jordan and Jones2008). The introduction of a new parasite is also expected to affect other parasites, especially those with similar life histories. The nature and long-term impacts of inter-parasite interactions, and their effects on hosts, is largely unknown but important for understanding marine disease dynamics.

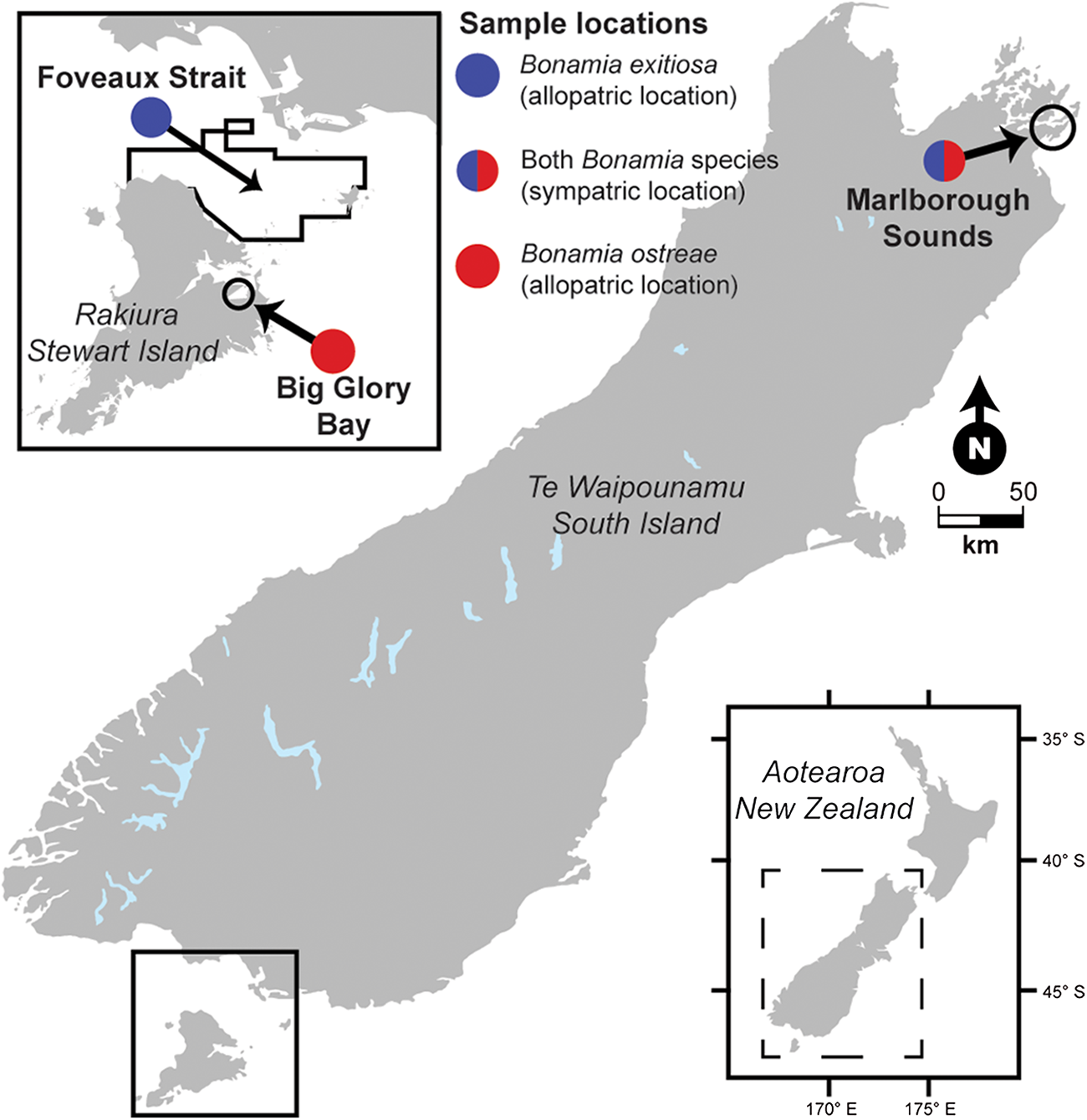

Two pathogenic haplosporidian oyster parasites Bonamia exitiosa and Bonamia ostreae infect New Zealand flat oysters Ostrea chilensis (Dinamani et al. Reference Dinamani, Hine and Jones1987; Lane et al. Reference Lane, Webb and Duncan2016). Bonamia exitiosa has a long history in New Zealand and is known to infect O. chilensis across much of their range, from Hauraki Gulf in the north to Port Adventure in the deep south (Dinamani et al. Reference Dinamani, Hine and Jones1987; Hine et al. Reference Hine, Cochennec-Laureau and Berthe2001; Lane et al. Reference Lane, Jones and Poulin2018). Bonamia ostreae was first detected in New Zealand in 2015 (Lane et al. Reference Lane, Webb and Duncan2016) and has since been confirmed in O. chilensis in the Marlborough Sounds and in Big Glory Bay, Stewart Island (Figure 1) (Lane et al. Reference Lane, Webb and Duncan2016; NIWA 2021). The detection of B. ostreae in New Zealand revealed O. chilensis coinfected with B. exitiosa (Lane et al. Reference Lane, Webb and Duncan2016). Concurrent Bonamia sp. infections have also been reported in Ostrea edulis from Italy, Spain and England, but with no data presented beyond detection prevalence (Abollo et al. Reference Abollo, Ramilo, Casas, Comesaña, Cao, Carballal and Villalba2008; Narcisi et al. Reference Narcisi, Arzul, Cargini, Mosca, Calzetta, Traversa, Robert, Joly, Chollet, Renault and Tiscar2010; Longshaw et al. Reference Longshaw, Stone, Wood, Green and White2013; Lane et al. Reference Lane, Webb and Duncan2016).

Figure 1. Illustrated map showing the confirmed locations for Bonamia exitiosa and Bonamia ostreae in New Zealand. Black lines show the approximate spread of collection sites within each sample location. See Table 1 for further information regarding the sample locations.

Bonamia exitiosa and B. ostreae have direct intra-haemocytic lifecycles. Individual parasites infect and replicate within phagocytic haemocytes, leading to parasite proliferation and host death (Hine and Wesney Reference Hine and Wesney1994; Hine Reference Hine1996; Hine et al. Reference Hine, Cochennec-Laureau and Berthe2001, Reference Hine, Carnegie, Kroeck, Villalba, Engelsma and Burreson2014; Comesaña et al. Reference Comesaña, Casas, Cao, Abollo, Arzul, Morga and Villalba2012). Given their evolutionary relatedness and similar life histories, sympatric B. exitiosa and B. ostreae could interact and compete for resources – namely the host haemocytes used for survival and reproduction. In situ hybridization (ISH) of concurrently infected animals has revealed that both parasites can be adjacent to one another in host tissues (Lane et al. Reference Lane, Webb and Duncan2016). Mixed infections of congeneric pathogenic parasites, such as vector borne terrestrial diseases like malaria and leishmania in vertebrates, can present more severe disease symptoms than single species infections (de Lima Celeste et al. Reference de Lima Celeste, Venuto Moura, França-Silva, de Sousa, Oliveira Silva, Norma Melo, Luiz Tafuri, Carvalho Souza and de Andrade2017; Shen et al. Reference Shen, Qu, Zhang, Li and Lv2019; Kotepui et al. Reference Kotepui, Kotepui, Milanez and Masangkay2020; Tang et al. Reference Tang, Templeton, Cao and Culleton2020). Mixed infections can also have varied antagonistic, additive, and synergistic effects, altering virulence and influencing host phenotype and reproductive fitness (Hafer and Milinski Reference Hafer and Milinski2015; Bose et al. Reference Bose, Kloesener and Schulte2016; Bolnick et al. Reference Bolnick, Arruda, Polania, Simonse, Padhiar, Rodgers and Roth-Monzón2024). Understanding disease dynamics within the oyster-Bonamia system is important for managing long-term impacts on host populations and oyster production. In New Zealand, bonamiasis has historically been caused by B. exitiosa, but the effects of B. ostreae, alone or in coinfection with B. exitiosa, remain unclear.

Droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) is a molecular testing technology similar to quantitative PCR (qPCR) that amplifies target DNA using thermocycling, but it partitions samples into thousands of droplets, enabling absolute quantification (Hindson et al. Reference Hindson, Ness, Masquelier, Belgrader, Heredia, Makarewicz, Bright, Lucero, Hiddessen, Legler, Kitano, Hodel, Petersen, Wyatt, Steenblock, Shah, Bousse, Troup, Mellen, Wittmann, Erndt, Cauley, Koehler, So, Dube, Rose, Montesclaros, Wang, Stumbo, Hodges, Romine, Milanovich, White, Regan, Karlin-Neumann, Hindson, Saxonov and Colston2011; Pinheiro et al. Reference Pinheiro, Coleman, Hindson, Herrmann, Hindson, Bhat and Emslie2012). This process removes the need for standard curves to provide a measurement of ‘gene copy number,’ which reflects how often a target sequence is detected. Gene copy number can serve as a proxy for infection intensity, with higher values indicating more intense infections (and vice versa; Bilewitch et al. Reference Bilewitch, Sutherland, Hulston, Forman and Keith2018; Barrett-Manako et al. Reference Barrett-Manako, Andersen, Martinez-Sanchez, Jenkins, Hunter, Reese-George, Montefiori, Wohlers, Rikkerink, Templeton and Nardozza2021; Howells et al. Reference Howells, Jaramillo, Brosnahan, Pande and Lane2021). Species specific ddPCR assays have been designed and validated for B. exitiosa and B. ostreae in O. chilensis (Bilewitch et al. Reference Bilewitch, Lane, Wiltshire, Deveney, Brooks and Michael2025). During assay validation, the number of B. exitiosa 18S rRNA gene copies detected was positively correlated with the number of Bonamia cells observed by cytology. Gene copy numbers increased with infection grade, with oysters classified as very heavy (grade 5) showing higher copy numbers than those with moderate (grade 3) or light infections (grade 1) (Bilewitch et al. Reference Bilewitch, Sutherland, Hulston, Forman and Keith2018). A similar relationship was observed during diagnostic validation comparing detection of B. ostreae using histopathology and ddPCR (Bilewitch et al. Reference Bilewitch, Lane, Wiltshire, Deveney, Brooks and Michael2025). Although specific quantitative test comparisons have only been carried out for B. exitiosa, we expect a similar parasite-gene copy number relationship for B. ostreae given their similar biology.

We used the two species-specific Bonamia ddPCR assays to investigate how infection intensities, inferred by gene copies, vary between an endemic and introduced parasite across allopatric and sympatric locations. We hypothesised that recently introduced B. ostreae would produce heavier infections, with higher gene copy numbers, than B. exitiosa, which has coevolved with their flat oyster hosts for longer. We expected that, given their direct intra-haemocytic life cycles, coinfection by the two parasite species would increase haemocyte parasitism and replication, resulting in higher gene copy numbers than in single species infections.

Materials and methods

Oyster samples

We used three pre-existing flat oyster collections from ongoing Bonamia spp. surveillance (Figure 1), which represent one sympatric and two allopatric sample locations for the Bonamia parasites: (1) oysters collected from the Marlborough Sounds in the upper South Island where B. exitiosa and B. ostreae are sympatric; (2) oysters collected from Big Glory Bay, Stewart Island where B. ostreae has been present since 2017 and there are no reported detections of B. exitiosa; and (3) oysters collected from Foveaux Strait, which remains free of B. ostreae, but where B. exitiosa was first reported in 1985 (Dinamani et al. Reference Dinamani, Hine and Jones1987) and later identified in archived specimens from the 1960s (Hine and Jones Reference Hine and Jones1994) (Figure 1). The prevalence of B. exitiosa in Marlborough Sounds was around 3%, B. ostreae was around 40% and concurrent infections around 50% (Lane et al. Reference Lane, Webb and Duncan2016). Bonamia ostreae has been detected at increasing prevalence in Big Glory Bay since its detection and is now around 30% (Bonamia Programme team 2023). Detection prevalence for B. exitiosa in Foveaux Strait sits at around 20% across the fishery area (Michael et al. Reference Michael, Forman, Smith, Brooks and Moss2023b).

Oysters from the Marlborough Sounds were collected in November 2014 and February 2015 from two farmed populations (Lane Reference Lane2018). Wild oysters from Big Glory Bay were collected during the six-monthly austral Spring and Autumn B. ostreae surveillance sampling conducted between 2021 and 2024 (NIWA 2021; Bonamia Programme team 2023; Bolnick et al. Reference Bolnick, Arruda, Polania, Simonse, Padhiar, Rodgers and Roth-Monzón2024). Wild oysters from the Foveaux Strait were collected during the annual late austral Summer/early Autumn B. exitiosa surveillance between 2021 and 2024 (Michael et al. Reference Michael, Bilewitch, Rexin, Forman, Hulston and Moss2022, Reference Michael, Bilewitch, Forman, Smith and Moss2023a, Reference Michael, Bilewitch, Forman, Smith and Moss2023a). The Foveaux Strait oysters were collected from 12 fixed target stations (see T-prefix in Michael et al. Reference Michael, Bilewitch, Rexin, Forman, Hulston and Moss2022). These fixed target stations were selected because they sample the same geographic location every year, which establishes a time series of data from across the entire Foveaux Strait flat oyster fishery. All sampled oysters were sexually mature. Marlborough Sounds and Foveaux Strait have marine salinities (∼35 psu), while Big Glory Bay has a salinity of around 18-20 psu.

ddPCR method

We screened heart tissues from all oysters using the species-specific Bonamia ddPCR assays that target the nuclear ribosomal 18S rRNA gene (Bilewitch et al. Reference Bilewitch, Lane, Wiltshire, Deveney, Brooks and Michael2025). A dual-probe ddPCR assay targeted the 18S rRNA gene of the parasite and the oyster β-actin gene (which served as an internal positive control for DNA extraction and amplification of each sample). Each ddPCR reaction was 24 µL in volume and consisted of BioRad ddPCR SuperMix, primers and probes, and 3 µL of the diluted tissue digest. A QX200 AutoDG Droplet Digital PCR System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) was used to automate droplet generation prior to amplification on a CFX PCR thermocycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) and droplet reading on a QX200 Droplet Reader (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). All plates were run with two additional controls: a synthetic positive control standard and a negative template control.

All heart tissue specimens, or heart tissue digests, were frozen in 96-well PCR plates archived at NIWA, Wellington on behalf of Biosecurity New Zealand and Fisheries New Zealand. For consistency, we tested heart tissue only across samples because gills may have surface contamination from environmental parasites and may not accurately represent an infection.

Only samples displaying successful amplification of the oyster β-actin internal control were included. Test outliers with no negative droplets (i.e. the samples are completely saturated with positive droplets) were excluded from subsequent analyses since Poisson calculations of target concentration were not possible. All test ddPCR results were converted to number of copies per 20 µL (cp/20 µL) and were tabulated in Microsoft Excel.

Statistics

A negative binomial generalized linear model (GLM) was used to test for differences in 18S rRNA gene copy numbers of Bonamia species among infection groups, defined by single versus concurrent infections across sympatric and allopatric sites. Marginal plots were generated to visualise estimated mean gene copies for each group and their 95% confidence intervals. A negative binomial GLM was chosen to account for overdispersion in the data (θ ranged from 0·27 to 0·34 across the four models [parasite sympatry in Marlborough Sounds, B. exitiosa-only, B. ostreae-only, and all location and infections groups]). Cook’s distance was calculated to identify potentially influential data points. All statistical analyses were performed using the R Statistical Software (v.4.4.2; R Core Team 2024) with the MASS package (v. 7.3.60.0.1) for fitting negative binomial GLMs, the emmeans package (v. 1.11.2) for estimated marginal means, and ggplot2 (v. 3.5.2) for visualization.

Results

A total of 409 ddPCR results were analysed (Table 1). Our sampling included single-species infections (B. exitiosa or B. ostreae), as well as coinfections where oysters were infected simultaneously by both parasites. Sampling was approximately even across infection groups (i.e. single infections and coinfections), but it was uneven across locations (Table 1). We removed 26 infected samples because they lacked negative droplets (n = 21 removed from Marlborough Sounds [B. ostreae only = 11, B. ostreae coinfections = 8, and B. exitiosa coinfections = 2], n = 4 removed from Big Glory Bay [all B. ostreae only], and n = 1 removed from Foveaux Strait [all B. exitiosa only]).

Table 1. Summary table of the 409 sampled ddPCR results across sample location and infection groups. The ddPCR results are from species-specific assays for each parasite. Single-species infections are ddPCR results for oysters infected by either Bonamia ostreae or Bonamia exitiosa. Coinfections represent ddPCR results for either parasite species, from oysters infected simultaneously by both B. ostreae and B. exitiosa (all from the Marlborough Sounds). Sampling is uneven between B. ostreae and B. exitiosa in the coinfected samples because some ddPCR results lacked negative droplets and were excluded

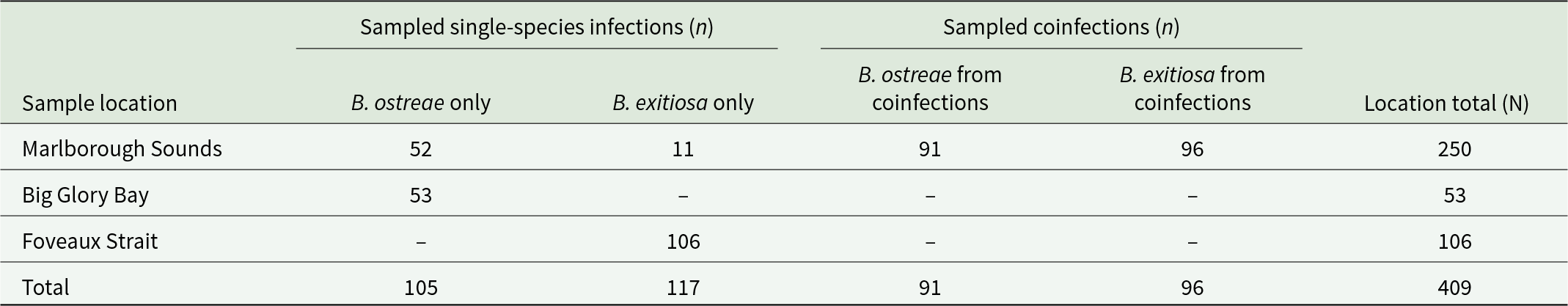

The range of Bonamia 18S rRNA gene copy numbers for each group spanned orders of magnitude (Figures 2–4). In the Marlborough Sounds where both parasites co-occur, a negative binomial GLM showed higher gene copy numbers in oysters infected with B. ostreae, with single infections having a∼ 3·2-fold increase and coinfections a ∼3·8-fold increase relative to B. exitiosa (both P < 0·001) (Table 2, Figure 2).

Figure 2. Variation in gene copy numbers (cp/20 µL) for oysters from the Marlborough Sounds, where Bonamia exitiosa and Bonamia ostreae are sympatric. 18S rRNA gene copies were estimated using the species-specific ddPCR assay for each Bonamia species. The sample groups show ddPCR results for single infections of either species, as well as results for each species in coinfected oysters. The black dot represents predicted means and error bars show 95% confidence intervals based on the negative binomial generalised linear model.

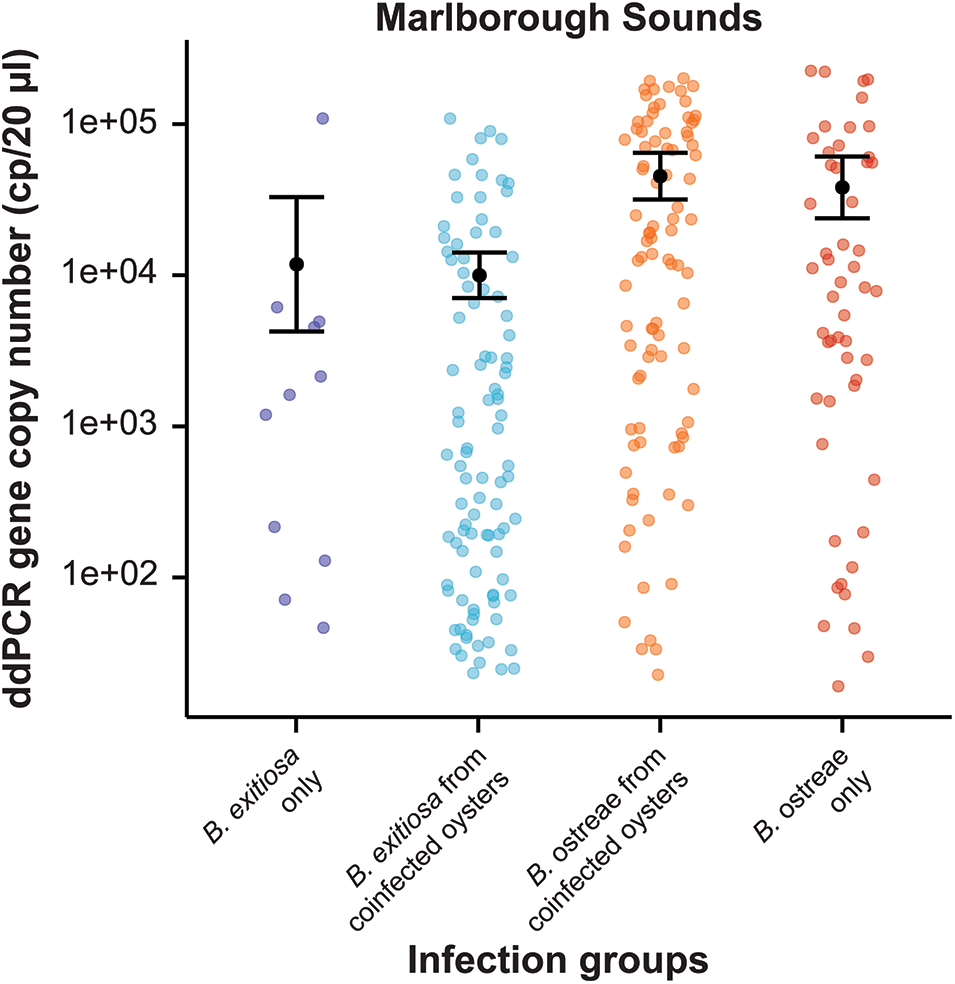

Figure 3. Variation in 18S rRNA gene copy numbers (cp/20 µL) between single and coinfections for (a) Bonamia exitiosa (including the influential data point identified by Cook’s distance) and (b) Bonamia ostreae, estimated using the species-specific ddPCR assay for each Bonamia species. The black dot represents predicted means and error bars show 95% confidence intervals based on the negative binomial generalised linear model. One oyster with a particularly high gene copy number for Bonamia exitiosa single-species infections is marked with a star.

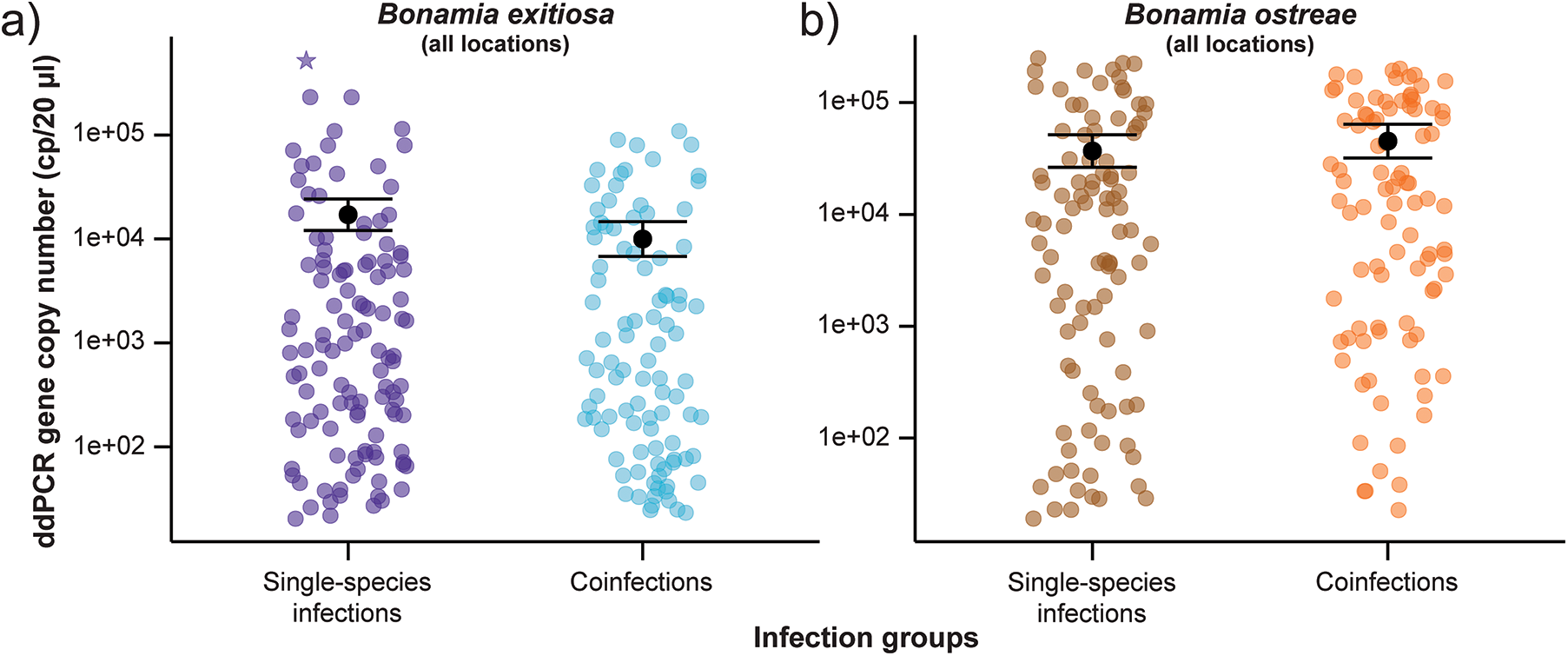

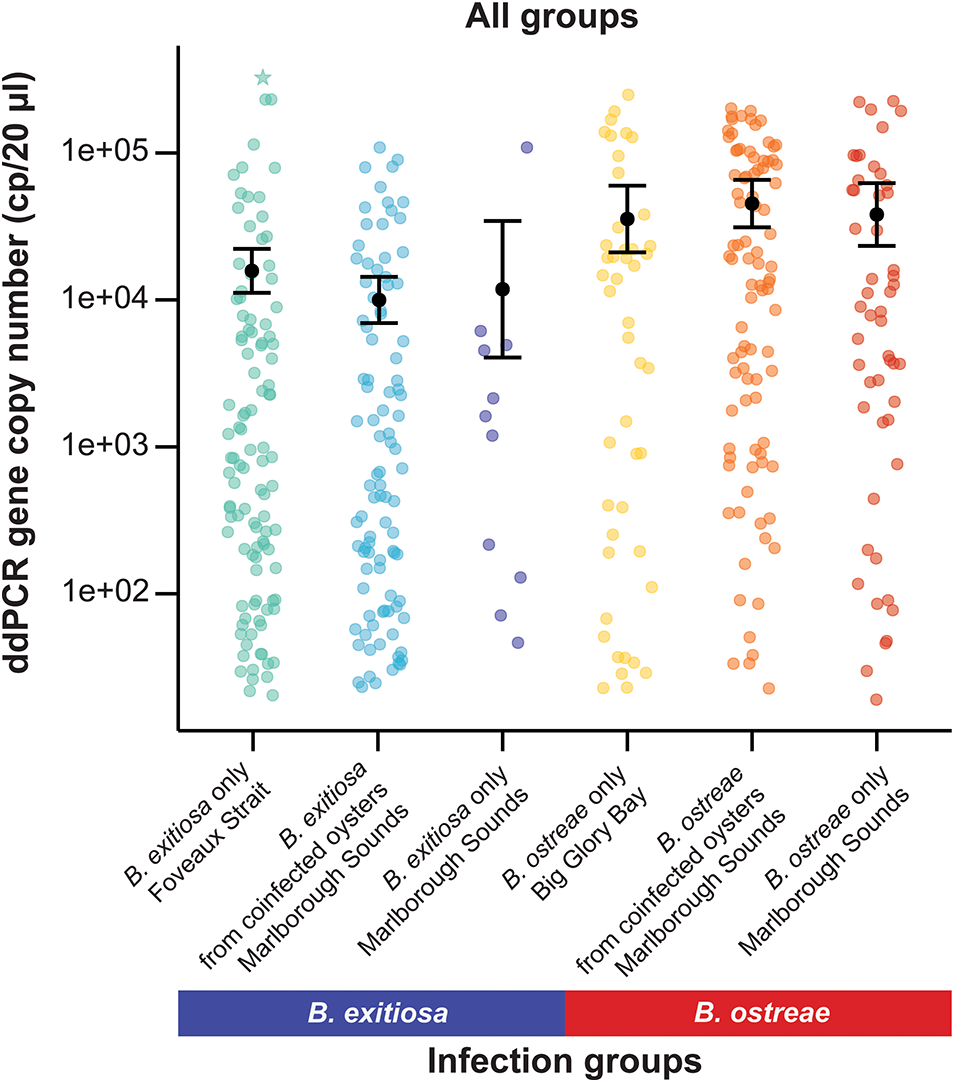

Figure 4. Variation in 18S rRNA gene copy numbers (cp/20 µL) among all tested oyster infection groups and locations. The black dot represents predicted means and error bars show 95% confidence intervals based on the negative binomial generalised linear model. One oyster with a particularly high gene copy number for B. exitiosa single-species infections is marked with a star.

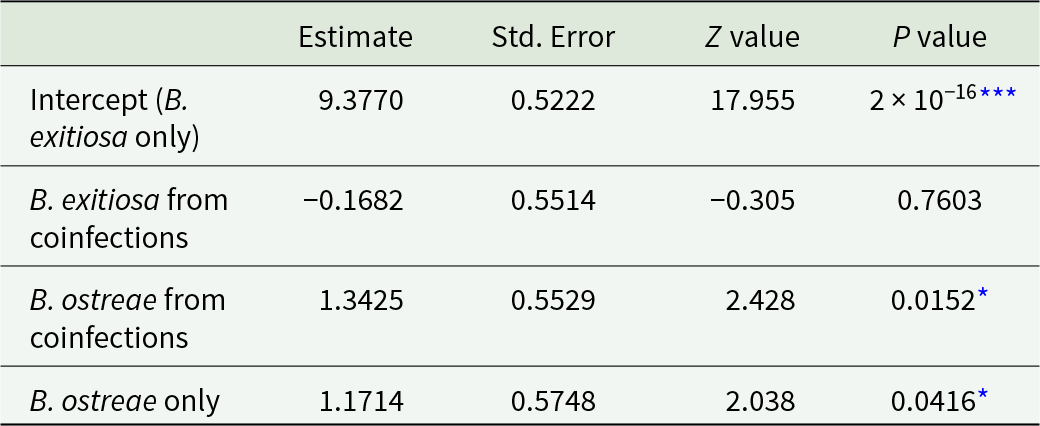

Table 2. Negative binomial generalized linear model comparing 18S rRNA gene copy numbers between single and coinfections of Bonamia ostreae and Bonamia exitiosa in flat oysters within their sympatric range in the Marlborough Sounds. The intercept represents B. exitiosa single infections and the coefficient for coinfections shows the effect relative to single infections. Estimates are reported on the log scale and exponentiating them gives fold changes relative to B. exitiosa single infections

P values < 0·05 are shown by

* and P values < 0·001 are shown by ***.

For B. ostreae, there was no detectable difference in gene copy numbers between single-species infections and coinfections (P = 0·4; Supplementary Table S1; Figure 3b). Whereas for B. exitiosa, gene copy numbers were 42% lower in coinfections than single infections (P = 0·04; Supplementary Table S2). Figure 3a shows one oyster with particularly high copy numbers, which was identified as an influential data point by Cook’s distance (>1·0; Supplementary Fig. S1). Removing it and rerunning the model reduced the estimated difference to ∼21% and the difference between single and coinfections was no longer statistically significant (P = 0·3; Supplementary Table S3), indicating that while B. exitiosa gene copies in coinfections are lower than in single-species infections, the statistical significance is sensitive to this single oyster.

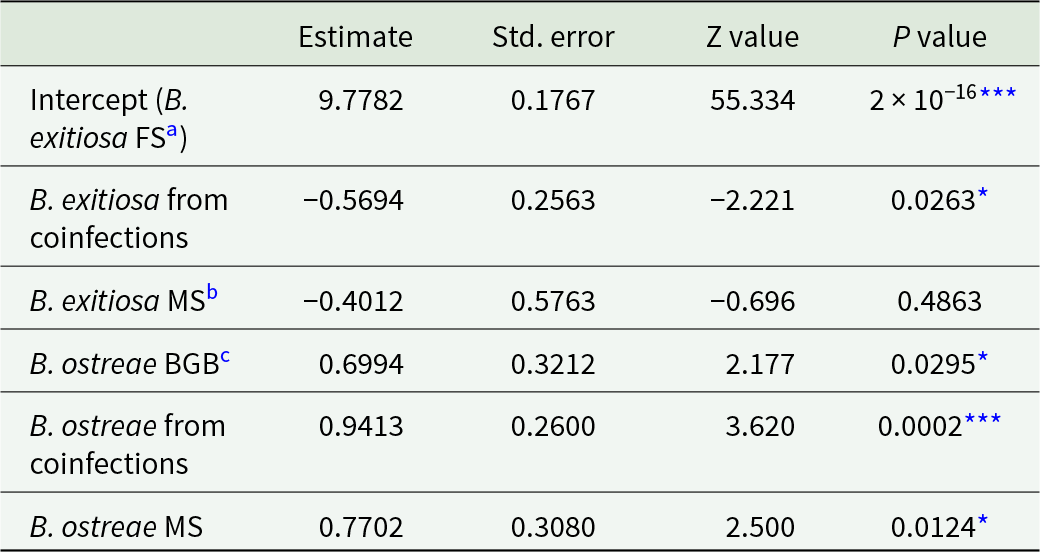

Across all infection groups and locations, B. ostreae consistently showed higher gene copy numbers compared to B. exitiosa (Table 3, Figures 2 and 4). For B. exitiosa, gene copy numbers from single-species infected and coinfected oysters in the Marlborough Sounds were 33% and 43%, respectively, lower than those from Foveaux Strait (Table 3). The oyster identified as influential in the B. exitiosa-only model was less influential in the combined model (Cook’s distance = 0·4; Fig. S2). Despite this, removing that oyster and rerunning the model maintained lower B. exitiosa gene copies in Marlborough Sounds, but the difference was no longer statistically significant (Supplementary Table S4).

Table 3. Negative binomial generalized linear model comparing 18S rRNA gene copy numbers between all locations and infection groups. The intercept represents Bonamia exitiosa single infections from Foveaux Strait and the coefficient for coinfections shows the effect relative to single infections. Estimates are reported on the log scale, exponentiating them gives fold changes relative to B. exitiosa Foveaux Strait

P values < 0·05 are shown by

* and P values < 0·001 are shown by ***.

a FS = Foveaux Strait.

b MS = Marlborough Sounds.

c BGB = Big Glory Bay.

Discussion

Infection intensity differs between Bonamia species

Gene copy numbers were significantly higher for B. ostreae than B. exitiosa across both allopatric and sympatric locations, supporting our hypothesis that a recently introduced parasite would produce higher infection intensities than a parasite with a longer evolutionary history with its host. While predicting the effects of invasive parasite species can be difficult, this result aligns with our expectations based on the reported pathogenicity of B. ostreae in Europe (Elston et al. Reference Elston, Farley and Kent1986) and the observed high mortality in the naive host population following the parasite’s arrival in New Zealand (Lane et al. Reference Lane, Webb and Duncan2016). While studies of other diseases have reported more severe symptoms in other mixed species infections (de Lima Celeste et al. Reference de Lima Celeste, Venuto Moura, França-Silva, de Sousa, Oliveira Silva, Norma Melo, Luiz Tafuri, Carvalho Souza and de Andrade2017; Shen et al. Reference Shen, Qu, Zhang, Li and Lv2019; Kotepui et al. Reference Kotepui, Kotepui, Milanez and Masangkay2020; Tang et al. Reference Tang, Templeton, Cao and Culleton2020), the overall outcomes for coinfections often seems to depend upon the density and frequency of parasite species (Alizon Reference Alizon2008, Reference Alizon2013; Bolnick et al. Reference Bolnick, Arruda, Polania, Simonse, Padhiar, Rodgers and Roth-Monzón2024). These factors are likely relevant for B. ostreae in New Zealand, as it is a recent arrival and presumably less common than B. exitiosa at sympatric locations.

Bonamia ostreae may cause more severe infections because it has only recently arrived and has not coevolved with New Zealand flat oysters. Since disease is a strong force of natural selection (Carnegie and Burreson Reference Carnegie and Burreson2011), it is almost certain that B. exitiosa and O. chilensis have exerted coevolutionary pressure on one another. The observed differences in infection intensities of B. exitiosa varied between locations, with oysters from Foveaux Strait having higher gene copy numbers than those from Marlborough Sounds (33-43% lower in Marlborough Sounds; Table 4). This difference may reflect host adaptation, as recurrent B. exitiosa epizootics in Foveaux Strait could have selected for some tolerance or resistance (Hine Reference Hine1996; Holbrook et al. Reference Holbrook, Bean, Lynch and Hauton2021). A more tolerant oyster is expected to survive with higher infection loads (Holbrook et al. Reference Holbrook, Bean, Lynch and Hauton2021), which may explain the higher average gene copy numbers observed. While this pattern is consistent with historical epizootics, uncovering the scale and nature of any adaptation of Foveaux Strait flat oysters to B. exitiosa is an important line of investigation into disease resilience and oyster management.

The consistently higher infection intensity, as inferred from gene copy number, for B. ostreae suggests that disease outcomes are species-driven and that B. ostreae will have a negative impact on oyster populations around New Zealand if it continues to spread. Theoretically, the strong selective pressure associated with high infection intensities and high mortality rates for B. ostreae infections may cause rapid adaptation among New Zealand flat oyster populations, provided mortality is not so high as to reduce spawner density below levels that would prevent future recruitment. In Europe, a consistent region of genomic variability has been identified for wild and farmed O. edulis populations that differ in resistance to B. ostreae (Vera et al. Reference Vera, Pardo, Cao, Vilas, Fernandez, Blanco, Gutierrez, Bean, Houston, Villalba and Martinez2019; Sambade et al. Reference Sambade, Casanova, Blanco, Gundappa, Bean, Macqueen, Houston, Villalba, Vera, Kamermans and Martinez2022). Given that B. ostreae has spread in Europe since the 1970s (Engelsma et al. Reference Engelsma, Culloty, Lynch, Arzul and Carnegie2014), this genomic variation has evolved swiftly within an ecological timescale. Although previous studies have doubted the feasibility of resilience breeding in New Zealand (Ross et al. Reference Ross, Boudry, Culloty, Michael, Wilkie and Lane2017; Culloty et al. Reference Culloty, Carnegie, Diggles, Deveney, Keith and Fansworth2020), future researchers could utilise a recent genome assembly (Rodríguez Piccoli Reference Rodríguez Piccoli2024) to determine whether a similar genomic region is present and suitable for selection in O. chilensis.

No detectable difference between concurrent and single-species infections

Concurrent infections in sympatric locations produced similar infection intensities to single-species infections, in disagreement with our second hypothesis. Gene copy numbers indicated that B. exitiosa and B. ostreae have no detectable interactions in concurrent infections. Our ddPCR results are concordant with a previous histopathological analysis, which sampled a subset of the same oysters collected from the Marlborough Sounds in 2015 (Lane Reference Lane2018). That study found no detectable differences in infection intensity between single-species and concurrent infections (Lane Reference Lane2018).

The absence of any detectable effect of coinfection compared to single infection on infection intensity is surprising, given the similar life-histories of B. exitiosa and B. ostreae. Indeed, a well-designed experimental infection could reveal previously unidentified changes in phenotype or tissue tropism of either species during a coinfection. Notably, future considerations need to be given to timing. Samples for this study were collected during fishery or biosecurity operations and therefore represent a sampling snapshot for parasite detection. Individuals with heavier infections could have died before sampling occurred, biasing results towards those individuals with lighter infections. The timing of each oyster’s exposure to B. exitiosa and B. ostreae during a concurrent infection, as well as the initial parasite load on host contact, are two important points that cannot be controlled given the nature of our dataset. For example, 100% mortality was observed in a mammalian host inoculated with two or more Plasmodia species at the same time (Tang et al. Reference Tang, Templeton, Cao and Culleton2020), whereas virulence tended to decrease, and specific parasite species were suppressed when inoculated at different times (Tang et al. Reference Tang, Templeton, Cao and Culleton2020). It needs to be tested whether similar effects occur with Bonamia spp. to provide greater confidence on the lack of interaction observed in this study.

Gene copy numbers remain a proxy of infection intensity and may be an imperfect reflection of biological reality. In lieu of a controlled experiment, however, they do provide a clear indication that there are more copies of the 18S rRNA gene from B. ostreae than B. exitiosa in an oyster sample. This infection pattern most likely indicates that there are more B. ostreae individuals than B. exitiosa inside oyster host heart tissue. Alternatively, B. ostreae may possess more copies of the 18S rRNA gene in its genome than B. exitiosa, which could bias the results towards B. ostreae. This hypothesis could be tested via further molecular investigation of both species. Regardless of any variation for the 18S rRNA gene between taxa, the absence of an interaction between B. exitiosa and B. ostreae in concurrent infections remains unchanged as those estimates depend on intraspecific (rather than interspecific) comparisons.

Conclusions

Our results show that B. ostreae has higher gene copies than B. exitiosa in New Zealand flat oysters, suggesting more intense infections, likely reflecting its recent introduction and lack of host-parasite co-adaptation. No significant differences in gene copies were observed between single and concurrent infections, suggesting coinfections do not intensify disease. These findings highlight B. ostreae as a continuing threat to O. chilensis, while emphasizing the need to assess the long-term impacts of both parasites. By examining congeneric coinfections, this study broadens understanding of Bonamia dynamics in New Zealand and underscores the importance of ecological and evolutionary context in marine disease research. Finally, infection intensity insights from gene copy numbers support the value of routine ddPCR screening for high-risk pathogens.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182025100978.

Acknowledgements

We thank everyone who has been involved with the Bonamia ostreae and B. exitiosa surveillance operations since their inception. The fishing industry including Bluff Oyster Management Company and Graeme Wright have been particularly supportive as well as Bruce Hearn from the Marlborough Sounds. We thank Biosecurity New Zealand and Fisheries New Zealand for funding the B. ostreae and B. exitiosa surveillance, respectively. Samples used in this study were collected through the following projects: Foveaux Strait: Fisheries NZ projects OYS202001 and OYS202301; Big Glory Bay: Biosecurity NZ projects SOW23611, SOW34679 and SOW36385. Flat oysters from Marlborough Sounds were collected as part of Henry Lane’s PhD thesis research. Finally, we want to thank the anonymous reviewer whose input significantly improved this manuscript.

Author’s contribution

HSL and FZ-V conceived and designed the study. JB, ARB, LS, KPM conducted oyster processing, data collection and dPCR testing. Funding for the ddPCR testing was obtained by MP and MD. HL performed statistical analysis. All authors contributed to results interpretation. HL, FZ-V wrote the draft article. All authors commented and reviewed article drafts.

Financial support

The work was funded by the New Zealand Ministry for Business, Innovation and Employment Strategic Science Innovation Fund under NIWA Coasts and Estuaries Biosecurity Research Programme.

Competing interests

The authors declare there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

Not applicable