Introduction

East Coast fever (ECF) is a highly prevalent and economically most important tick-borne disease of cattle in sub-Saharan Africa caused by Theileria parva, a highly pathogenic protozoan parasite (Oligo et al., Reference Oligo, Nanteza, Nsubuga, Musoba, Kazibwe and Lubega2023). The disease is transmitted by the brown ear tick, Rhipicephalus appendiculatus, and primarily affects cattle, targeting lymphocytes and leading to severe immunosuppression and, in extreme cases, death of cattle (Marcotty et al., Reference Marcotty, Speybroeck, Berkvens, Chaka, Besa, Madder, Dolan, Losson and Brandt2004; Zweygarth et al., Reference Zweygarth, Nijhof, Knorr, Ahmed, Al-Hosary, Obara, Bishop, Josemans and Clausen2020; Latre de Late et al., Reference Latre de Late, Cook, Wragg, Poole, Ndambuki, Miyunga, Chepkwony, Mwaura, Ndiwa, Prettejohn, Sitt, Van Aardt, Morrison, Prendergast and Toye2021). Traditional control methods for theileriosis, including acaricide treatment and anti-theilerial drugs, have encountered challenges, necessitating the development of effective vaccines (Oligo et al., Reference Oligo, Nanteza, Nsubuga, Musoba, Kazibwe and Lubega2023). However, developing an effective conventional vaccine has been challenging due to the limited understanding of the necessary immune mechanisms and how to stimulate them (Nene and Morrison, Reference Nene and Morrison2016).

The Muguga cocktail vaccine (MCV), infection and treatment method (ITM) stand as an effective control measure against ECF. The MCV consists of live sporozoites of 3 strains of T. parva, namely Kiambu 5, Muguga and Serengeti transformed (Steinaa et al., Reference Steinaa, Svitek, Awino, Njoroge, Saya, Morrison and Toye2018). Immunization through infection and treatment involves the simultaneous inoculation of live T. parva sporozoites alongside long-acting oxytetracycline treatment (Marcotty et al., Reference Marcotty, Speybroeck, Berkvens, Chaka, Besa, Madder, Dolan, Losson and Brandt2004). At a certain immunization dose, the MCV has shown to be able to elicit appropriate immunological responses (Allan and Peters, Reference Allan and Peters2021); however, it is not yet known if all 3 strains contribute equally to this reaction.

Previous in vitro studies have focused on examining the cocktail as a whole than studying the unique contributions of each strain in the cocktail (Patel et al., Reference Patel, Mwaura, Kiara, Morzaria, Peters and Toye2016). Furthermore, it is difficult to ascertain how each of these strains contributes to the overall effectiveness of the vaccination due to their differing levels of virulence as observed in vivo studies. Consequently, to have a better understanding of their roles in eliciting immunity, it is necessary to examine the in vitro infectivity of individual stabilates produced from each strain (Oligo et al., Reference Oligo, Nanteza, Nsubuga, Musoba, Kazibwe and Lubega2023). Therefore, the current study evaluated the in vitro infectivity of Kiambu 5, Muguga and Serengeti transformed strains found in the MCV stabilates using the peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from a naïve bovine donor.

Materials and methods

Study site

The study was conducted at the African Union Centre for Ticks and Tick-Borne Diseases (AU-CTTBD) in Lilongwe, Malawi. The AU-CTTBD is a regional centre specializing in vaccine production and research for tick-borne diseases, provided the necessary facilities, equipment, and expertise for this study.

Preparation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells

PBMCs were prepared using a modified protocol adapted from Marcotty et al. (Reference Marcotty, Speybroeck, Berkvens, Chaka, Besa, Madder, Dolan, Losson and Brandt2004). The whole blood was collected aseptically from a single healthy Friesian bull maintained at AU-CTTBD. This animal was confirmed to be naïve for T. parva exposure by serology and health records. Using a sterile 20 mL syringe prefilled with 10 mL of warmed Alsevers solution (Gibco, ThermoFisher, USA) as an anticoagulant and cell preservative, approximately 10 mL of jugular blood was drawn. The blood-Alsevers mixture was gently transferred into a 50 mL Falcon centrifuge tube.

A density gradient separation was performed by carefully layering 17 mL of blood on top of Histopaque (Sigma-Aldrich, USA). The tube was centrifuged at 900 × g for 30 min at room temperature without brakes to allow for optimal separation of cell layers. The resulting interface band of white blood cells was collected using a sterile Pasteur pipette. This interface was resuspended in 10 mL of Alsevers solution to wash residual plasma and platelets and centrifuged again at 800 × g for 15 min with brakes (acceleration and deceleration set to 5).

To lyse residual erythrocytes, the cell pellet was resuspended in 500 µL of cold sterile water, and Alsevers solution was immediately added up to 35 mL to stop osmotic lysis. This suspension was centrifuged at 800 × g for 15 min. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was resuspended in serum-free RPMI-1640 medium. A TC20 automated cell counter (Bio-Rad Laboratories, USA) was used to determine cell concentration, which was adjusted to 2 × 106 cells mL−1.

PBMCs were obtained from a single healthy Friesian donor animal for several reasons. First, the use of 1 donor ensured that sufficient cells could be isolated at the required concentration (2 × 106 cells mL−1) to complete all experimental replicates under identical conditions, avoiding batch-to-batch variability. Second, utilizing PBMCs from a single animal minimized inter-animal immunological variability in cell susceptibility to infection, which is known to influence schizont development and infectivity rates in vitro (Speybroeck et al., Reference Speybroeck, Marcotty, Aerts, Dolan, Williams, Lauer, Molenberghs, Burzykowski, Mulumba and Berkvens2008). This approach allowed us to attribute observed differences in infectivity primarily to the properties of each T. parva strain and the inoculum concentration, rather than to host-related differences in innate or adaptive immune responsiveness. Third, by standardizing the cell source, we enhanced reproducibility and comparability across the 3 experimental runs conducted approximately 10 days apart. While this design choice may limit the generalizability of findings to other hosts, it was critical for maintaining experimental consistency and generating clear, interpretable comparisons among the strains under controlled conditions.

The cell suspension was transferred into T50 culture flasks and incubated overnight at 4 °C to facilitate cell stabilization and adherence of monocytes. The following day, non-adherent cells were gently resuspended in fresh RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 20% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; ThermoFisher, USA), penicillin G (100 IU mL−1), streptomycin (100 µg mL−1) and amphotericin B (0.25 µg mL−1). These antibiotics and antifungal agents were included to suppress bacterial and fungal contaminants commonly associated with tick homogenates used to prepare sporozoite stabilates. Their doses were selected based on established protocols for in vitro PBMC culture (Zweygarth et al., Reference Zweygarth, Nijhof, Knorr, Ahmed, Al-Hosary, Obara, Bishop, Josemans and Clausen2020) to ensure effective microbial control while preserving cell viability and parasite infectivity (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Experimental workflow of Theileria parva infection to bovine peripheral blood mononuclear cells.

In vitro infections of T. parva in the PBMCs

The seed stabilates used in this trial were ILRI 4228 Kiambu 5, produced at ILRI in 2008, ILRI 4230 Muguga, produced at ILRI in 2008, and Ser04 Serengeti transformed, produced at CTTBD in 2022. Ser04 is a daughter of Ser02 produced at CTTBD in 2013 from Serengeti transformed ILRI 4229 which was produced at ILRI in 2008 as described by Patel et al. (Reference Patel, Mwaura, Kiara, Morzaria, Peters and Toye2016) for the production of ILRI 4228, ILRI 4230 and ILRI 4229 which are employed in the production of the MC vaccine.

Three concentrations were selected for comparative infectivity testing: 2.75, 84.5 and 169 infected acini/mL. The lowest concentration, 2.75 infected acini/mL, corresponds to the standard field immunization dose and is equivalent to a 1:100 dilution of a stabilate with a titre of 275.53 infected acini/ml, as recommended in vaccine administration protocols (Patel et al., Reference Patel, Mwaura, Kiara, Morzaria, Peters and Toye2016). The intermediate (84.5 infected acini/mL) and higher (169 infected acini/mL) concentrations were included to explore infectivity at increased stabilate titres. While previous studies have often employed serial 2-fold dilution schemes for dose titration, the aim of the present study was to assess whether each strain contributes equally to infection establishment when tested independently at uniform absolute concentrations (Wilkie et al., Reference Wilkie, Kirvar and Brown2002; Marcotty et al., Reference Marcotty, Speybroeck, Berkvens, Chaka, Besa, Madder, Dolan, Losson and Brandt2004; Tindih et al., Reference Tindih, Marcotty, Naessens, Goddeeris and Geysen2010). This approach enables clearer evaluation of strain-specific infectivity, which cannot be distinguished in vivo due to the combined nature of the vaccine formulation.

Each strain was tested in 3 independent experimental runs initiated approximately 10 days apart. This time-staggered design was implemented to assess reproducibility across temporally separated batches and to manage workflow, reducing the likelihood that findings were influenced by batch-specific variation or transient laboratory conditions. For each run, the prepared PBMCs were seeded into 96-well flat-bottom plates and inoculated with stabilate dilutions in triplicate sets of wells.

The plates were sealed to minimize evaporation and reduce contamination risks and were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO₂ for 10 days. This incubation environment replicated bovine physiological conditions: 37 °C approximates the normal body temperature of cattle, while 5% CO₂ maintains bicarbonate-buffered medium pH between 7.2 and 7.4, critical for PBMC viability and optimal schizont development. The 10-day duration was selected based on evidence that schizonts become reliably detectable between days 4 and 10 in vitro (Tindih et al., Reference Tindih, Marcotty, Naessens, Goddeeris and Geysen2010).

Justification of selected concentrations

The neat stabilate titres of Muguga (676 infected acini/mL) and Kiambu 5 (169 infected acini/mL) have been previously reported (Patel et al., Reference Patel, Mwaura, Kiara, Morzaria, Peters and Toye2016). The Serengeti transformed stabilate used in this study (Ser04) had a titre of 284.08 infected acini/mL and was produced at CTTBD in 2022. Ser04 is a daughter of Ser02, itself derived from ILRI 4229 (titre 529 infected acini/ml as reported by Patel et al., Reference Patel, Mwaura, Kiara, Morzaria, Peters and Toye2016). These titres informed the selection of absolute concentrations in the present study, enabling equitable comparison across strains. While serial 2-fold dilutions are commonly employed in titration studies, such an approach would have yielded inherently disparate absolute doses across strains due to these baseline titre differences. This disparity would confound interpretation by primarily reflecting the relative abundance of sporozoites rather than their intrinsic infectivity potential per unit volume. By contrast, selecting the same absolute infected acini/mL concentrations allowed each strain to be evaluated under directly comparable conditions. The lowest concentration (2.75 infected acini/mL) corresponds to the field immunization dose recommended in the MCV, which is considered sufficient to establish infection and generate protective immunity in vivo (Patel et al., Reference Patel, Mwaura, Kiara, Morzaria, Peters and Toye2016). This makes it a biologically relevant reference point for assessing infectivity under conditions that approximate actual vaccine administration. The intermediate (84.5 infected acini/mL) and higher (169 infected acini/mL) concentrations were chosen to simulate operational scenarios where stabilate batches may be used at higher titres during vaccine preparation or where dilution inaccuracies could occur. Evaluating infectivity at these higher doses also allowed exploration of whether increasing inoculum results in proportionally higher infectivity or introduces limitations such as microbial contamination or saturation effects on PBMC cultures. Importantly, this strategy facilitated the assessment of each strain’s infectivity performance across a gradient of doses that are both practically and biologically relevant, rather than producing a purely dilution-based infectivity curve that would lack comparability across strains. In this way, the chosen concentrations provide a robust framework for understanding strain-specific infectivity independent of initial stabilate titre, supporting conclusions about their relative contributions to infection establishment in vitro.

Cytospin smears and visualization on microscope

On day 10 post-infection, samples from each well were collected, and cytospin smears were prepared using a cytocentrifuge. Smears were subsequently Giemsa-stained to visualize T. parva schizonts within infected cells. Each well was scored as positive or negative for infection based on the microscopic presence or absence of schizonts. Wells in which bacterial overgrowth or fungal hyphae precluded reliable evaluation were recorded as missing data (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Micrographs of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (A) after separation before infection, and arrow in (B) and (C) show schizonts in T. Parva infected lymphocytes.

Data analysis

In this experiment, infectivity results were recorded and managed using Microsoft Excel spreadsheets, which were structured to include strain identity, well identifiers, time points and infectivity status. For the final analysis, data from all 3 experimental runs were pooled to calculate overall frequencies of positive, negative, and missing wells for each strain at each concentration. This approach ensured an adequate sample size and avoided disproportionate weighting of variability from individual runs.

Statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS; IBM Corp., https://www.ibm.com/analytics/spss-statistics-software). Differences in infectivity rates among strains across concentrations were assessed using the Chi-square test, with post hoc pairwise comparisons conducted using Bonferroni correction. Statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.05. Line graphs were generated to visualize trends and highlight significant differences. Both statistical and biological significance were considered in the interpretation of results.

Results

Infectivity rates of Theileria parva strains

Muguga strain

At 2.75 infected acini/mL, the Muguga strain showed a positive infectivity rate of 76.8%, a negative rate of 23.2%, and no wells recorded as missing data (Figure S1). At 84.5 infected acini/ml, the positive infectivity rate was 23.4%, the negative rate was 17.2%, and 59.4% were recorded as missing data (Figure S2). At 169 infected acini/ml, no wells demonstrated positive infectivity. The negative rate was 6.3%, and 93.8% were classified as missing data (Figure S3).

Kiambu 5 strain

At 2.75 infected acini/ml, the Kiambu 5 strain had a positive infectivity rate of 51.8%, a negative rate of 26.8%, and 21.4% missing data (Figure S1). At 84.5 infected acini/ml, the positive infectivity rate was 28.1%, the negative rate was 37.5%, and 34.4% missing data (Figure S2). At 169 infected acini/mL, no positive infectivity was observed. The negative rate was 3.1%, and 96.9% missing data (Figure S3).

Serengeti transformed strain

At 2.75 infected acini/mL, the Serengeti transformed strain showed a positive infectivity rate of 57.1%, a negative rate of 28.6%, and 14.3% missing data (Figure S1). At 84.5 infected acini/mL, the positive infectivity rate was 10.9%, the negative rate was 10.9%, and 78.1% missing data (Figure S2). At 169 infected acini/ml, the positive infectivity rate was 15.6%, the negative rate was 12.5%, and 71.9% missing data (Figure S3).

Comparison of in vitro infectivity of Theileria parva strains

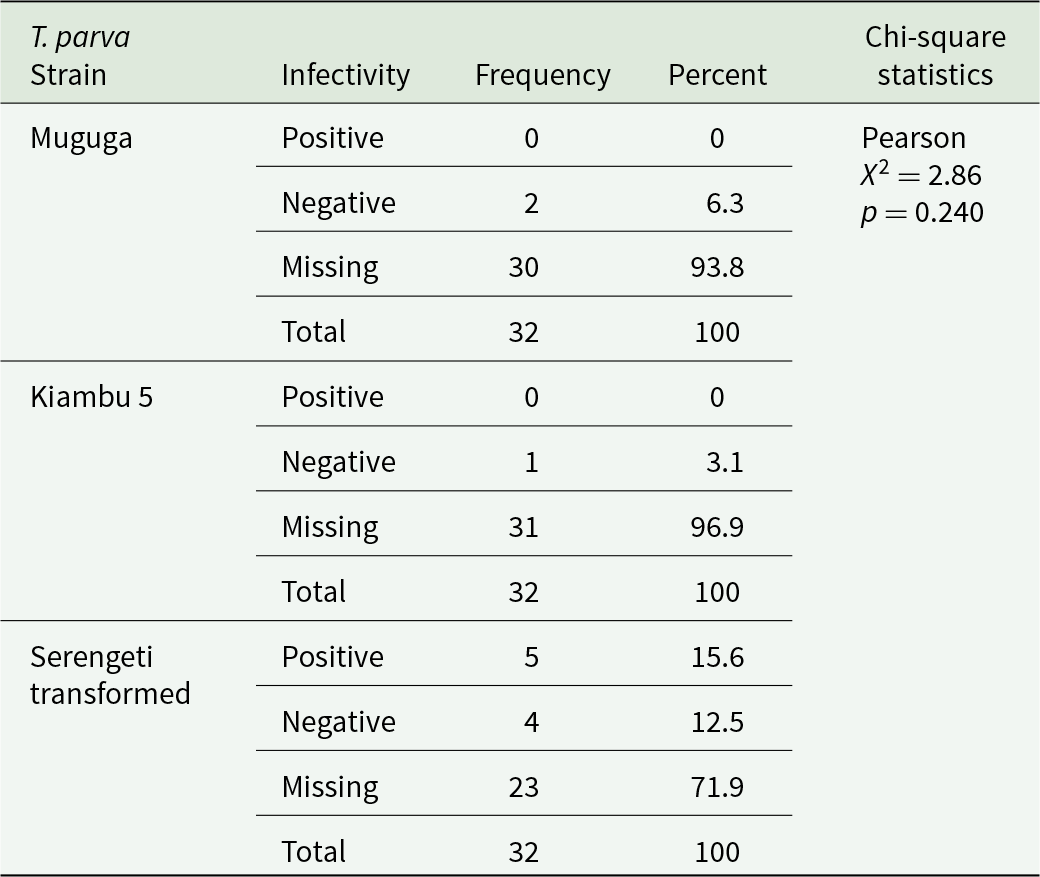

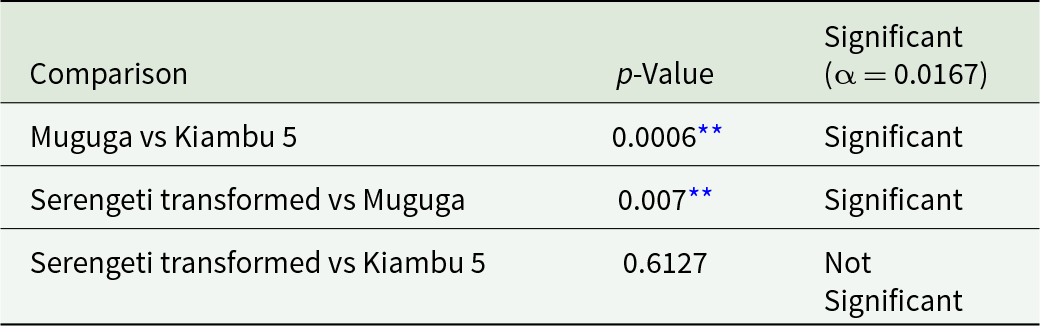

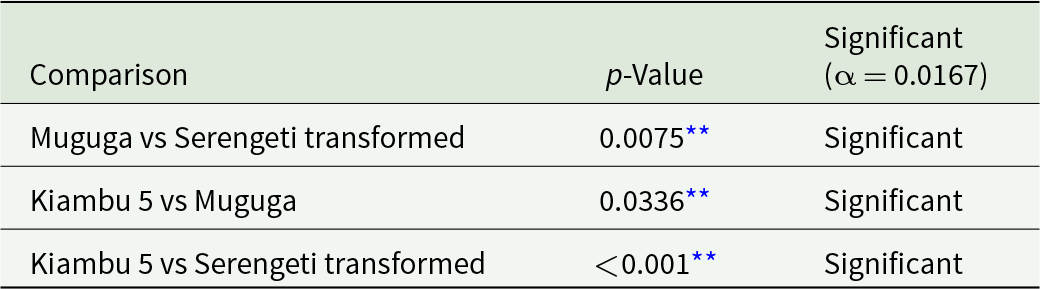

At 2.75 infected acini/mL, the Chi-square test demonstrated a significant association between strain type and infectivity status (χ2 = 14.65, p < 0.005) (Table 1). At 84.5 infected acini/mL, a significant association was also observed (χ2 = 26.90, p < 0.001) (Table 2). At 169 infected acini/mL, no statistically significant association was detected (χ2 = 2.86, p = 0.240) (Table 3). Post hoc pairwise comparisons using Bonferroni correction are presented in Tables 4 and 5.

Table 1. Frequency distributions of in vitro infections of T. Parva strains at 2.75 infected acini/mL

** Confidence interval = 95% and significance level p ≤ 0.05.

Table 2. Frequency distributions of in vitro infections of T. Parva strains at 84.5 infected acini/mL

** Confidence interval = 95% and significance level p ≤ 0.05.

Table 3. Frequency distributions of in vitro infections of T. Parva strains at 169 infected acini/mL

Confidence interval = 95% and ** significance level p ≤ 0.05.

Table 4. Post hoc pairwise comparisons (chi-square tests with Bonferroni correction)

** Confidence interval = 95% and significance level p ≤ 0.05.

Table 5. Post hoc pairwise comparisons (chi-square tests with Bonferroni correction)

** Confidence interval = 95% and significance level p ≤ 0.05.

Discussion

While in vitro infectivity does not equate directly to immunogenicity, it provides an important indication of a stabilate’s capacity to establish infection in host cells, which is a necessary step in inducing protective immune responses following immunization (Oura et al., Reference Oura, Bishop, Wampande, Lubega and Tait2004; Patel et al., Reference Patel, Mwaura, Kiara, Morzaria, Peters and Toye2016). Nevertheless, in vitro assays remain an essential tool for preclinical evaluation of stabilate viability and comparative performance. In this study, we assessed the in vitro infectivity of the 3 T. parva strains Muguga, Kiambu 5, and Serengeti transformed that constitute the MCV, using PBMCs derived from a naïve bovine donor. To our knowledge, this is among the few studies to compare infectivity of these strains at equivalent concentrations individually, thereby contributing new insights into their potential relative roles in vaccine efficacy.

At the field immunization dose of 2.75 infected acini/ml, the Muguga strain demonstrated consistently higher infectivity (76.8% positive wells) compared to Kiambu 5 (51.8%) and Serengeti transformed (57.1%). This difference was statistically significant (χ2 = 14.65, p < 0.005) and aligns with previous reports highlighting Muguga’s robust performance in vitro (Tindih et al., Reference Tindih, Marcotty, Naessens, Goddeeris and Geysen2010). These findings suggest that Muguga may play a particularly prominent role in early infection events, which could be relevant for prompt immune priming following vaccination. However, it is important to recognize that in vitro infectivity reflects the capacity to infect PBMCs under controlled conditions, and further in vivo studies are necessary to confirm whether these differences translate into variations in protective immunity.

At the intermediate concentration of 84.5 infected acini/mL, infectivity declined overall, with the Kiambu 5 strain showing a higher proportion of positive wells (28.1%) compared to Muguga (23.4%) and Serengeti transformed (10.9%). The chi-square analysis confirmed significant differences among strains at this dose (χ2 = 26.90, p < 0.001). Notably, the decline in infectivity was accompanied by an increase in missing data due to contamination, which accounted for up to 59.4% of wells in the Muguga group and 78.1% in the Serengeti transformed group.

At the highest concentration tested (169 infected acini/ml), the Serengeti transformed strain demonstrated relatively higher infectivity (15.6% positive wells) than Muguga (0%) and Kiambu 5 (0%). However, the overall chi-square test at this dose did not reach statistical significance (χ2 = 2.86, p = 0.240), likely due to the overwhelming proportion of missing data caused by contamination exceeding 70% across all strains.

The selection of the 3 concentrations was intentional and reflects realistic production scenarios. While serial 2-fold dilutions have been used in dose titration studies to define minimal protective doses (Patel et al., Reference Patel, Mwaura, Kiara, Morzaria, Peters and Toye2016), the present design aimed to evaluate infectivity of each strain individually at comparable absolute concentrations. This approach is valuable for understanding whether the strains contribute equally to establishing infection, which is difficult to ascertain when administered together in a cocktail. By using doses that reflect the approximate range of field applications and potential variations during vaccine preparation, we provide data relevant to both research and manufacturing settings.

The use of PBMCs from a single bovine donor was a strategic choice to reduce inter-animal variability and ensure consistent infection conditions across all experiments. While this limits the generalizability of the findings, it enhances reproducibility and clarity in identifying strain-specific effects. Future studies involving PBMCs from multiple animals will be important to confirm the observed patterns and broaden applicability.

In addition, by pooling results from 3 independent experimental runs initiated approximately 10 days apart, we ensured that the findings were robust and not driven by run-specific variability. This approach increased statistical power, minimized the risk of overinterpreting temporal fluctuations, and strengthened confidence that the observed strain-specific differences reflect true biological variation rather than experimental noise.

Contamination of wells was more frequent at higher concentrations, particularly at 169 infected acini/ml, highlighting a persistent challenge inherent to tick-derived stabilate preparations (Marcotty et al., Reference Marcotty, Speybroeck, Berkvens, Chaka, Besa, Madder, Dolan, Losson and Brandt2004; Mbao et al., Reference Mbao, Berkvens, Dolan, Speybroeck, Brandt, Dorny, Van den Bossche and Marcotty2006). Despite the inclusion of antibiotics and antifungal agents at validated concentrations (Zweygarth et al., Reference Zweygarth, Nijhof, Knorr, Ahmed, Al-Hosary, Obara, Bishop, Josemans and Clausen2020), microbial overgrowth still impacted the proportion of interpretable data. This challenge is largely attributable to the inherent properties of the tick-derived material used to prepare sporozoite stabilates. Because sporozoites are obtained by homogenizing whole infected ticks, the resulting preparations inevitably contain microbial contaminants originating from the tick’s tissues and gut flora. Conventional sterilization methods such as filtration, irradiation, or heat treatment are not applicable, as they would inactivate the live sporozoites required for immunization. Therefore, even under rigorous laboratory conditions and with the use of antimicrobial agents, complete elimination of contaminants is not feasible without compromising vaccine efficacy. This unavoidable trade-off underscores the importance of optimizing contamination control measures. Approaches such as pre-screening tick material for contaminant profiles and tailoring antimicrobial regimens may help to mitigate this limitation in future work.

Despite these challenges, this study provides novel comparative data on individual strain infectivity at standardized concentrations, filling a gap in the literature on MCV characterization. The insights gained can also guide improvements in vaccine production standards and quality assurance protocols.

In conclusion, our findings indicate that individual strains within the MCV exhibit distinct in vitro infectivity profiles across different concentrations. The Muguga strain showed higher infectivity at the field immunization dose, whereas the Serengeti transformed strain demonstrated comparatively greater infectivity at the highest concentration tested. These results support the importance of strain-specific evaluations to better characterize the contributions of each component in live sporozoite vaccines. Future studies incorporating multiple donor animals, improved contamination control, and molecular assays will help to build on these results and further strengthen the evidence base for optimizing ECF vaccination strategies.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182025101443.

Data availability statement

The data is available upon request from the corresponding author for valid use to duplicate published papers or answer secondary research questions.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the management of the AU-CTTBD in Lilongwe, Malawi for allowing us to conduct this study at their institution. Further, we would like to acknowledge the following technical staff; Mr Osbert Pangani and Mr. Nashon Kamwendo for their assistance during this study.

Author contributions

WM, GC and EC: conceived and designed the study. WM and GC: Investigation. WM, GC and EC: performed statistical analyses. GC, EC: Supervision and project administration. WM, GC, EC: wrote the original manuscript. GC, EP, HK, TK, FM, RN and KH: Writing reviews and editing. All authors approved the submitted version for publication.

Financial support

This study received financial support from the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), Kenya, and the African Union Centre of Excellence for Ticks and Tick-Borne Diseases (AU-CTTBD), Malawi. The funders did not influence the design of the study or the preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

All the procedures used in this study were approved by the Animal Health and Research Committee of the Department of Animal Health and Livestock Development (DAHLD) in the Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security, Malawi with the Reference number DAHLD/AHC/04/2023/017. All procedures adhered to established ethical standards for research involving animal-derived samples and the laws of Malawi.

Declaration of generative AI in scientific writing

Generative artificial intelligence (AI) and AI-assisted technologies were NOT used in the writing process.