Introduction

The global expansion of invasive molluscs has become a critical driver of neglected tropical disease (NTD) transmission, with Angiostrongylus cantonensis, a parasitic nematode that causes eosinophilic meningitis in humans and neurological disease in other vertebrates, posing an increasing public health and veterinary threat in Southeast Asia and China (Wan et al., Reference Wan, Sun, Wu, Yu, Wang, Lin, Li, Wu and Sun2018; Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Jiang, Fang, Chen, Liu, Zhao, Andrus, Li and Guo2024; Li et al., Reference Li, Liu, Fang, Zhao, Li, Jiang, Andrus, Guo and Chen2025). Angiostrongylus cantonensis passes through 2 moults inside its intermediate gastropod host, transforming from first-stage (L1) to second-stage (L2) and finally into infective third-stage larvae (L3) that transmit the parasite to definitive vertebrate hosts (Griffin et al., Reference Griffin, Ezenwa and Cowie2025; Li et al., Reference Li, Liu, Fang, Zhao, Li, Jiang, Andrus, Guo and Chen2025). Since 1961, numerous human cases have been documented, primarily linked to the accidental ingestion of intermediate snail hosts (Villanueva et al., Reference Villanueva, Munoz, Martinez, Cruz, Prieto-Alvarado and Liscano2024; Hasan et al., Reference Hasan, Nourse, Heney, Lee, Kapoor and Berkhout2025; Li et al., Reference Li, Liu, Fang, Zhao, Li, Jiang, Andrus, Guo and Chen2025). Among these hosts, 2 freshwater species, Biomphalaria straminea (Gastropoda: Planorbidae) and Physa acuta (Gastropoda: Physidae), both invasive in China, have spread across various regions of Guangdong province (Cao et al., Reference Cao, Zhuang and Hu2014; Lin et al., Reference Lin, Zeng, Sanogo, He, Xiang, Du, Zhang, Wang, Wan, Zeng, Yang, Lv, Liang, Deng, Hui, Yuan, Ding, Wu and Sun2020, Reference Lin, Xiang, Sanogo, Liang, Sun and Wu2021; He et al., Reference He, Hu, Khan, Huang, Yuan, Sanogo, Gao, Liu, Wu, Chen, Wu, Liang, Sun and Lin2025). Snail species like Pomacea canaliculata, B. glabrata and Lissachatina fulica are well-established reservoirs for A. cantonensis (Yousif and Lammler, Reference Yousif and Lammler1975; Song et al., Reference Song, Wang, Yang, Lv and Wu2016; Boraldi et al., Reference Boraldi, Lofaro, Bergamini, Ferrari and Malagoli2021; Anettova et al., Reference Anettova, Sipkova, Balaz, Hambal, Coufal, Kacmarikova, Vanda, Eka and Modry2025). Additionally, the native (non-invasive) Chinese gastropod species, such as Cipangopaludina chinensis and Bellamya aeruginosa, are capable of transmitting the parasite and are commonly consumed by humans (Li et al., Reference Li, Hong, Yuan, Huang, Wu, Ding, Wu, Sun and Lin2023; Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Jiang, Fang, Chen, Liu, Zhao, Andrus, Li and Guo2024). In contrast, B. straminea and P. acuta are small-bodied species that are rarely eaten, making them less likely to directly infect people. However, they can still create localized hotspots of transmission that affect wildlife like rats.

Biomphalaria straminea is a known intermediate host for schistosomiasis in the wetlands of Guangdong, southern China (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Zeng, Sanogo, He, Xiang, Du, Zhang, Wang, Wan, Zeng, Yang, Lv, Liang, Deng, Hui, Yuan, Ding, Wu and Sun2020, Reference Lin, Xiang, Sanogo, Liang, Sun and Wu2021; He et al., Reference He, Hu, Khan, Huang, Yuan, Sanogo, Gao, Liu, Wu, Chen, Wu, Liang, Sun and Lin2025), yet its role in A. cantonensis transmission has not been systematically evaluated. Similarly, P. acuta is an important intermediate host for A. cantonensis (Li et al., Reference Li, Fang, Chen, Yang, Zhao, Zhao, LI, Yang, Guo and Liu2024), yet the molecular mechanisms underlying its susceptibility remain unclear. These gaps may hinder risk prediction and targeted control of snail hosts. Further research is needed to explore the ecological and molecular factors that contribute to the susceptibility of these understudied species.

While many studies on snail-parasite interactions, including those involving A. cantonensis, have explored multiple adult snail host species across a size gradient (with shell diameters typically greater than 2 cm) (Song et al., Reference Song, Wang, Yang, Lv and Wu2016; Zhiyuan et al., Reference Zhiyuan, YI, Yunhai, Zhiqiang, Yun, Wei and Guangyao2019; Lima et al., Reference Lima, Augusto, Pinheiro and Thiengo2020; Lopes-Torres et al., Reference Lopes-Torres, De Oliveira, Mota and Thiengo2023), research on immune adaptations in small-bodied snail species, such as B. straminea and P. acuta (with shell diameters typically less than 2 cm), remains comparatively limited. For example, while P. canaliculata demonstrates dose-dependent larval loads and suppressed α-tubulin expression during A. cantonensis infection (Zhi-Yuan et al., Reference Zhi-Yuan, Yi, Yun-Hai, Zhi-Qiang, Yun and Wei2019; Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Jiang, Fang, Chen, Liu, Zhao, Andrus, Li and Guo2024), similar data for other snail species like P. acuta are lacking. Additionally, previous research on B. glabrata revealed temperature-dependent larval survival (optimal at 26 ºC) and size-specific susceptibility patterns (Yousif and Lammler, Reference Yousif and Lammler1975), but it is unknown whether these factors also apply to the invasive congener B. straminea in China.

In this study, we conducted preliminary research on the comparative analysis of A. cantonensis infection dynamics in P. acuta and A. cantonensis from Guangdong Province, southern China, as well as on the potential interaction mechanisms between P. acuta and A. cantonensis. Our study aims not only to clarify the differences and dynamic changes in snail susceptibility to A. cantonensis infection but also to advance the mechanistic understanding of host-parasite coevolution in small-bodied snail species.

Materials and methods

Snail animal study

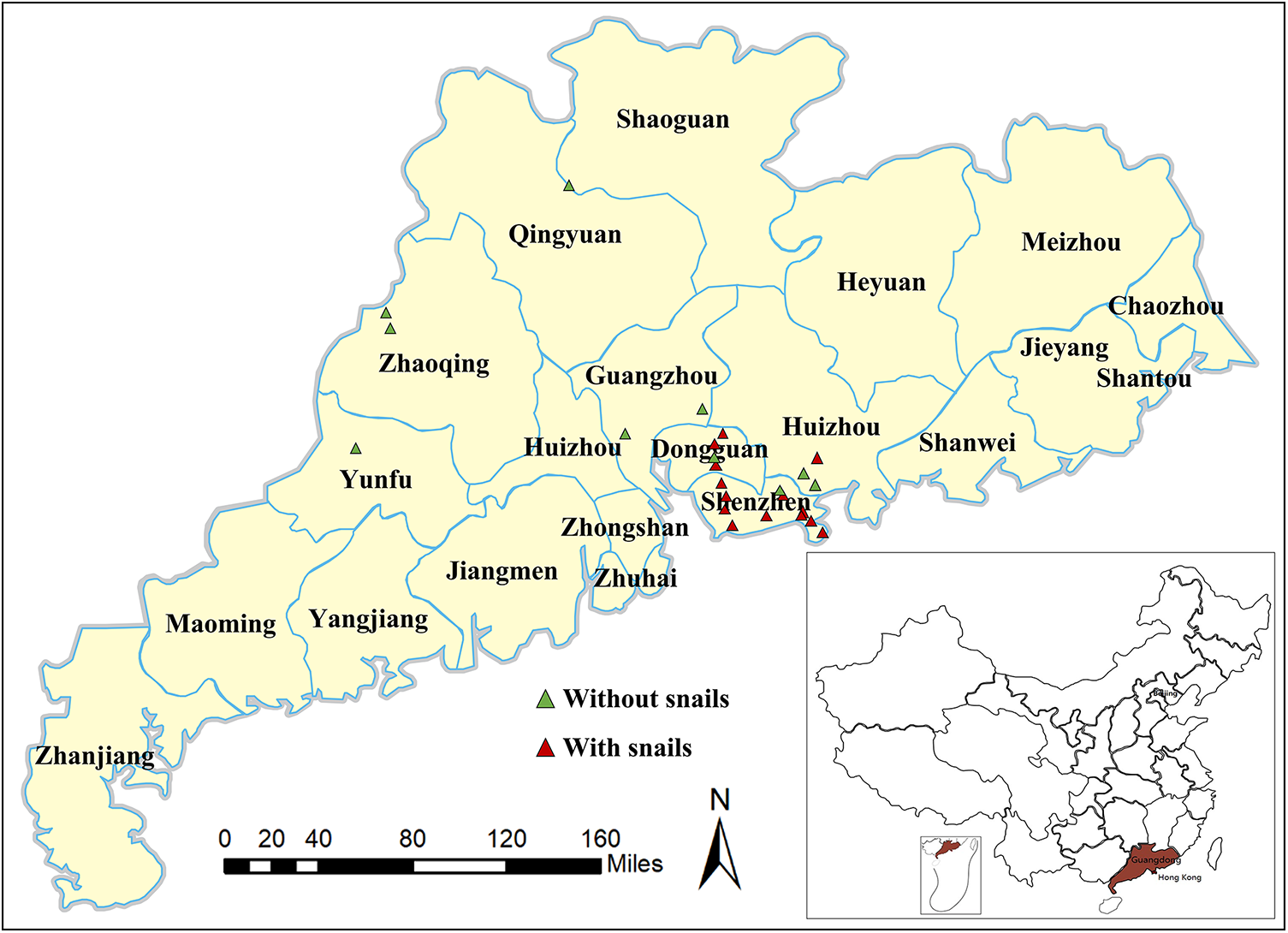

Wild B. straminea and P. acuta were collected from 3 sampling sites across Guangdong Province (Zhaoqing, Qingyuan and Guangzhou) between 2015 and 2017. The number of snails collected at each site ranged from 30 to 100 per species, and the GPS coordinates of all surveyed locations were recorded (see Figure 1 and Table S1). Following initial collection, a subset of wild snails was used to establish laboratory colonies, with species identity first determined through basic morphological analysis (e.g. shell shape and size) and later confirmed by molecular methods, including mitochondrial COI barcoding (He et al., Reference He, Hu, Khan, Huang, Yuan, Sanogo, Gao, Liu, Wu, Chen, Wu, Liang, Sun and Lin2025). These cultured snails were F1 or F2 generations derived from the wild founders and were maintained in species-specific aquaria at Zhongshan School of Medicine, Sun Yat-sen University, China. Both wild-caught and laboratory-reared snails were maintained in separate aquariums in the laboratory. Laboratory-reared B. glabrata snails have been maintained for over 15 years. The water temperature was maintained at 25 ± 1 °C, with a 12 h light/12 h dark cycle (08:00–20:00 light period). Sterilized commercial fish feed was provided once daily, and any uneaten food was removed during water changes every 48 h. For pre-experiment screening, a subset of snails (n = 30 per species) was anesthetized by immersion in cold water (4 °C) for 30 min, after which their shells were gently removed using sterilized metal tweezers under a stereomicroscope, similar to previous studies (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Hong, Sanogo, Du, Xiang, Hui, Ding, Wu and Sun2023). Soft tissues were then inspected for visible signs of helminth infection, such as motile larvae or cyst-like structures, to ensure that snails were free from pre-existing parasitic infections prior to experimental exposure. The shell diameter was measured with a Vernier caliper.

Figure 1. The map shows the snail sampling sites in Guangdong, China. Green triangles indicate the sites where P. Acuta snails were found.

Biomphalaria straminea snails collected from the same habitats exhibited distinct phenotypic variations in shell colour, specifically black and red shell phenotypes. These phenotypes were included in the infection study to assess any potential differences in susceptibility to A. cantonensis. The black-shell phenotype included 36 individuals, and the red-shell phenotype included 10 individuals for the infection experiment.

Parasite strain

The A. cantonensis strain (Guangzhou, 2013) was originally isolated from wild Lissachatina fulica collected in Baiyun District, Guangzhou, China. The parasite was maintained via cyclic passage in Sprague Dawley rats housed at the ABSL-2 facility of Zhongshan School of Medicine, SYSU. First-stage larvae (L1) were harvested from faecal samples of infected rats using a modified Baermann funnel technique, as described previously (Gu et al., Reference Gu, Liu, Li, Luo, LI, Chen and Zhan2008; Xie et al., Reference Xie, Yuan, Luo, Zeng, Zeng, He, Lv and Wu2017) and stored in dechlorinated water at room temperature overnight (for no longer than 24 h) prior to use in infection experiments. The L1 were then purified and counted, maintaining high activity during this process.

Parasite infection experiments

The feces were passed through a 200-mesh sieve (74 μm pore size), and the L1 larvae were concentrated via sedimentation at 25–27 °C overnight. To quantify larval concentration, the sedimented suspension was drawn from the bottom of the beaker using a Pasteur pipette and transferred into wells of a 6-well culture plate. If needed, the suspension was diluted with dechlorinated water to adjust the larval load. After gentle mixing, a measured aliquot (100 µL) was placed onto a glass slide, fixed with microiodine alcohol and examined under a dissecting microscope. The number of L1 larvae per unit volume was counted to determine the average larval load. L1 larvae measured approximately 150 µm in length.

Infection doses were as follows: P. acuta (500, 1000, 2000 L1/snail; n = 10 per group) and B. straminea (500, 1000, 2000, 4000, 10 000 L1/snail; n = 10 snails per treatment group). For each species, 10 uninfected individuals served as negative controls. As a positive control, B. glabrata (n = 10) was infected with 2000 L1 larvae to benchmark infection dynamics against a well-established permissive host, providing a comparative reference for assessing the susceptibility of B. straminea at the same genus level.

To encourage the ingestion of larvae by snails, all snails were starved for 24 h immediately prior to infection. They were then exposed individually to the L1 suspension (5 mL) in 6-well plates for 24 h at room temperature. After exposure, snails were returned to standard rearing conditions, housed separately by species and group in 1000 mL containers with dechlorinated water (replaced every 48 h), maintained at 25 ± 1 °C under a 12 h light/12 h dark cycle. Snails were fed sterilized fish feed daily to prevent competition and potential cross-contamination between species. All exposures and post-infection housing were performed in the same facility.

Study of infection rate, larvae load and survival rate

Third-stage larvae (L3) were quantified at 3 weeks post-infection for B. straminea and 4 weeks post-infection for P. acuta to account for differences in parasite development timelines. These timeframes were selected based on prior studies indicating peak L3 recovery at 3 weeks for B. straminea (Xie et al., Reference Xie, Yuan, Luo, Zeng, Zeng, He, Lv and Wu2017) and 4 weeks for P. acuta under similar experimental conditions. At the appropriate time, snails were humanely euthanized by cold immersion (4 °C for 30 min) to minimize stress before dissection. Shells were removed, and soft tissues were carefully chopped into small pieces using ophthalmic scissors. The tissue was then digested with a pepsin-HCl solution (1.5 g pepsin (1:10 000), 7 mL HCl, 1 L dechlorinated water) at 37 °C for 1 h. After digestion, the suspension was collected using a Pasteur pipette and transferred to a 60-mm culture dish. The L3 larvae were rinsed with dechlorinated water to remove any residual acid before being counted under dark-field microscopy. Snail mortality was recorded daily until 4 weeks post-infection, and survival curves were constructed based on the percentage of live snails. Snail mortality was recorded as the number of snails that died during the experimental period.

Selection of physa acuta strains for susceptibility study

The susceptibility of P. acuta from different geographic regions (Qingyuan and Zhaoqing) was assessed based on L3 larvae load (number of larvae per snail) and infection rates observed in the initial dose-response experiments. In laboratory experiments, snails from Qingyuan (with low susceptibility, characterized by <10 L3 larvae per snail) and Zhaoqing (with high susceptibility, characterized by >30 L3 larvae per snail) were exposed to various infection doses to determine their relative susceptibility. Then, the egg masses produced by infected snails were hatched to obtain the F1 generation. The F1 snails were reared individually in 50-mL beakers and exposed to 1000 L1 per snail at adulthood to ensure consistency with the infection protocols. To establish low-susceptibility and susceptible lines, selective breeding was carried out over 2 generations. The Qingyuan-F2 population was established by selecting snails from each geographic region that exhibited consistent resistance or susceptibility to A. cantonensis infection. Specifically, Qingyuan-F2 snails displayed reduced L3 larvae loads, indicating a level of partial resistance rather than complete immunity, while Zhaoqing-P0 snails showed higher L3 larvae loads, confirming their susceptibility. Finally, to compare immune responses, we assessed relative transcription levels of immune-related genes between the low-susceptibility and susceptible lines using real-time PCR.

RNA extraction and real-time PCR

Both P. acuta strains, representing differing susceptibility levels (Qingyuan-F2 and Zhaoqing-P0), were infected simultaneously with A. cantonensis. Individuals (n = 100) from the F2 generation of each strain were exposed to 500 L1 larvae per snail. Additionally, ten uninfected snails from each strain were used as control groups. At various time points post-infection (0.5, 1, 2, 3, 7, 14 and 21 days), 10 snails were randomly taken from each experimental group. After anaesthesia, the snails’ shells were removed, and their tissues were immediately immersed in TRIzol reagent and stored at −80 °C for future processing. Before lysing, the tissue samples were homogenized using a tissue homogenizer capable of maintaining a temperature of 4 °C to facilitate better RNA extraction. RNA extraction was completed by lysing the tissue samples with TRIzol reagent, following the manufacturer’s instructions. After extraction, the total RNA was stored at −80 °C until further analysis. The concentration of total RNA in each sample was measured using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer. RNA integrity was confirmed using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer.

Quantitative RT-PCR was performed using the SYBR Green dye technology and more details are shown in Tables S2-S3. Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized from 1.5 µg of total RNA using oligo (dT) primers and a Thermo Scientific RevertAid First Strand cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis was performed using a SYBR Green PCR Master Mix kit (Applied Biosystems, USA) on a Light Cycler 480 detection system (Roche, Switzerland). The relative mRNA expression levels of the target genes refer to the quantification of their mRNA abundance in comparison to the internal control (actin), with normalization using the comparative Ct method. Primer sequences targeting immune genes and housekeeping controls (actin) are listed in Table S4. Fold-changes were calculated using the 2-ΔΔCT method with inter-run calibrators.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) using GraphPad Prism (v. 5.0; GraphPad, USA). The differences between experimental groups (i.e. P. acuta strains with different susceptibility, different infection doses, or time points post-infection) were analysed with a 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) using SPSS 19.0 software. Survival curves were compared by the log-rank test (GraphPad Prism v5.0). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Susceptibility of biomphalaria straminea to angiostrongylus cantonensis

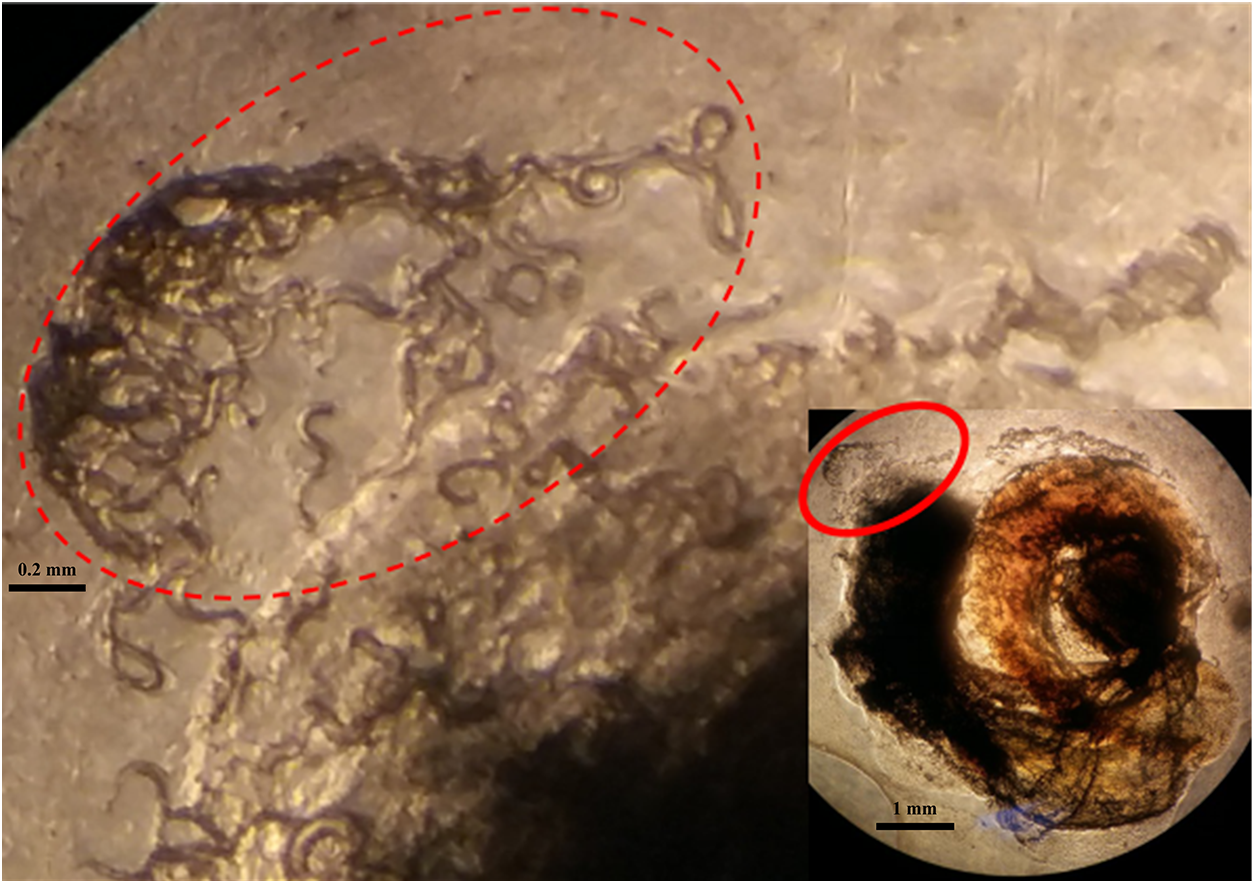

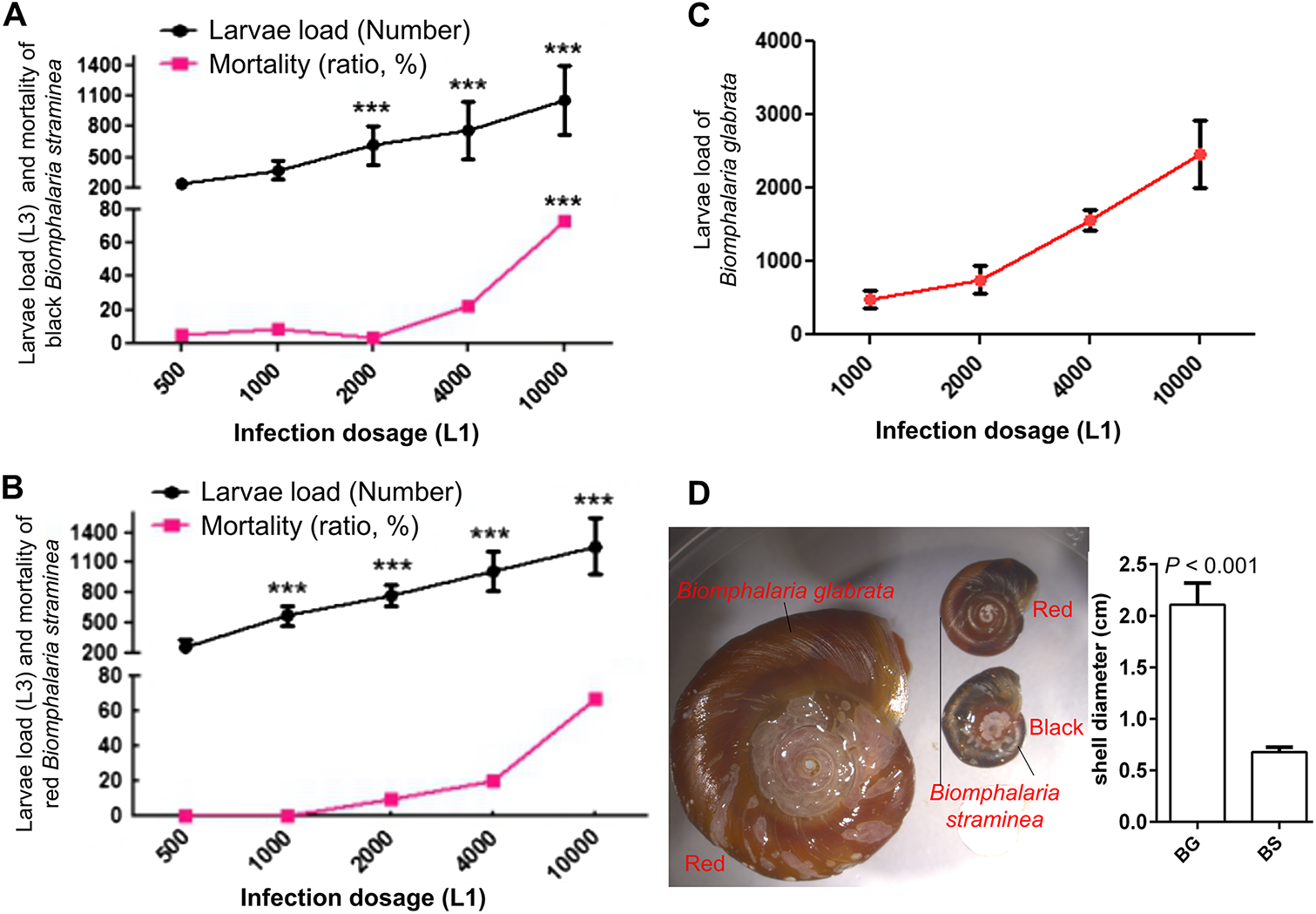

After exposure to L1 larvae under laboratory conditions, wild-caught B. straminea exhibited a 100% proportion of individuals infected with A. cantonensis, with the third-stage larvae (L3) localized at the peripheral soft tissues (Figure 2). Larval load in both black-shell (n = 36) and red-shell (n = 10) phenotypes increased dose-dependently (500 to 10 000 first-stage larvae (L1)/snail), peaking at 765 ± 142 L3 per snail (Figure 3A, B). Mortality remained ≤10% at doses ≦2000 L1 but surged to 65% at 10 000 L1 (P < 0.001). Compared to the positive control group, B. straminea infected with 2000 L1 larvae showed a slightly lower larval load (620 ± 186) than B. glabrata infected with 2000 L1 (756 ± 185) (Figure 3C). Despite its smaller body size (6.782 ± 0.014 mm) compared to B. glabrata (Figure 3D), B. straminea exhibited a similar larval load, demonstrating its high suitability. However, when comparing larval load (i.e. number of L3 per snail), B. straminea tolerated a higher load of L3 than B. glabrata.

Figure 2. Angiostrongylus cantonensis larval (L3) localization in Biomphalaria straminea tissues. L3 larvae (red oval circle) clustered at soft tissue margins.

Figure 3. Dose–response relationships in Biomphalaria spp. A Black-shell B. Straminea (n = 36). B Red-shell B. Straminea (n = 10). C Larval load comparison with B. Glabrata (n = 10). D Shell diameter between adult B. Glabrata (BG) and B. Straminea (BS) snails. ***indicates a significant difference compared to the 500 L1 group (P < 0.001).

Susceptibility of physa acuta to angiostrongylus cantonensis

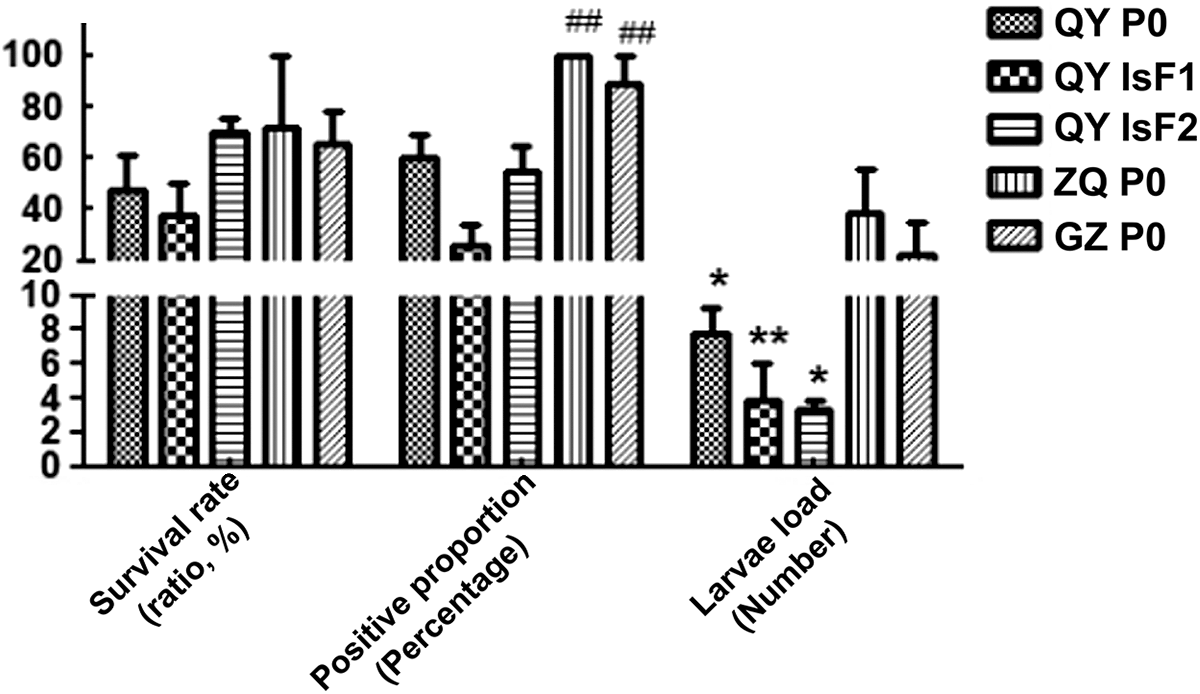

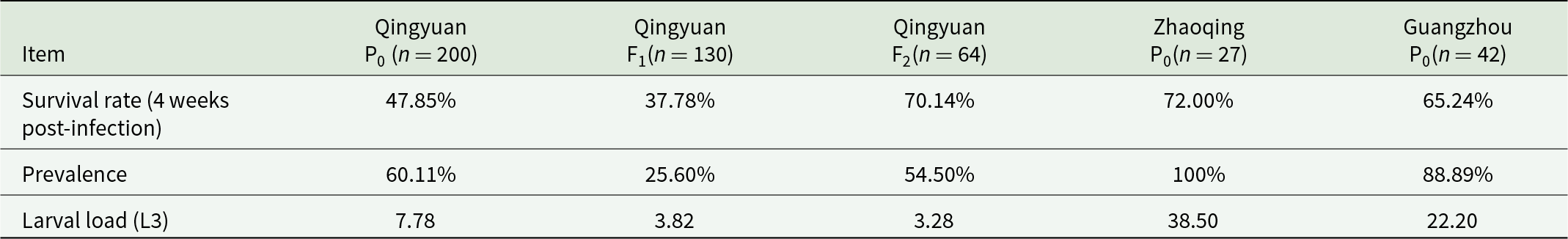

Wild P. acuta strains from Guangdong showed distinct susceptibility differences: Qingyuan-P0 (7.8 ± 2.1 L3 per snail; P < 0.05) compared to Zhaoqing-P0 and Guangzhou-P0 (Table 1). The positivity rate and L3 larvae load of P. acuta from Qingyuan were lower than those from Zhaoqing and all Guangzhou strains. Selective breeding stabilized low susceptibility in the low-susceptible Qingyuan-F2 strain (3.3 ± 1.2 L3/snail), while susceptibility persisted in Zhaoqing-P0 (41.8 ± 5.9 L3/snail) (Figure 4). Survival rates were inversely correlated with larval load (r = − 0.83, P < 0.001).

Figure 4. Geographic and generational susceptibility trends of P. Acuta strains. QY, Qingyuan City; ZQ, Zhaoqing City; GZ, Guangzhou; P0, parental generation; F1, the first generation of low susceptibility strain; F2, the second generation of low susceptibility strain. ## Represented a significance compared with group QY F1 (P < 0.01). **Represented a significance compared with group ZQ P0 (P < 0.01).

Table 1. Infection metrics across P. Acuta strains. P0: parental generation. F1: the first generation of low susceptibility strain. F2: the second generation of low susceptibility strain

Susceptibility mechanisms of physa acuta to angiostrongylus cantonensis

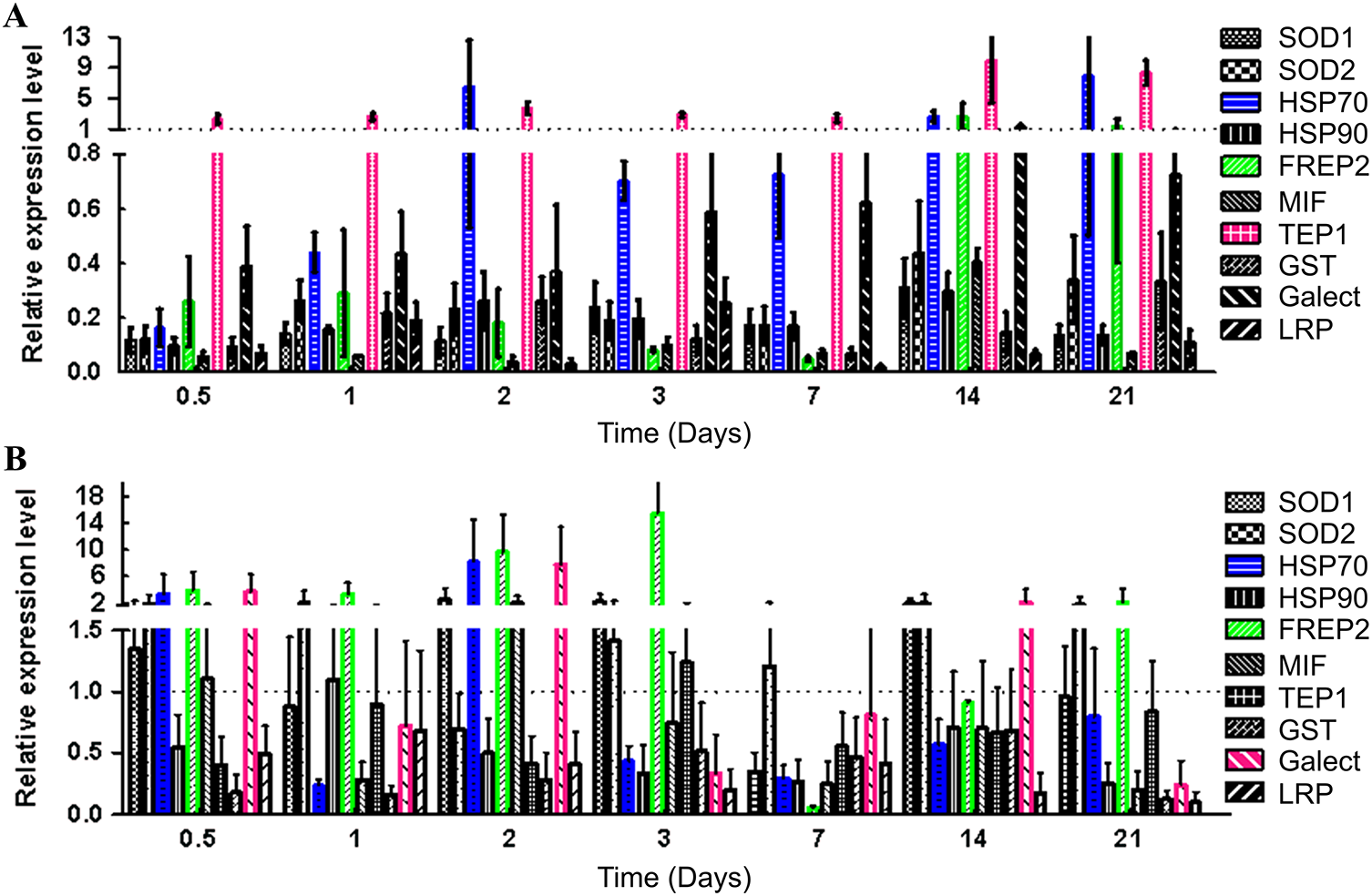

Transcriptional profiling of 10 immune-related genes revealed clear differences between the high-susceptible and low-susceptible P. acuta strains (Figure 5). These genes included pattern recognition proteins (FREP2, Galectin), immune regulatory factors (MIF, TEP1, LRP) and oxidative stress-related proteins (Cu-Zn_SOD1, Fe-Mn_SOD2, HSP70, HSP90, GST). The susceptible strain (classified as susceptible due to its higher larval load) exhibited delayed upregulation of TEP1, a thioester-containing protein involved in pathogen recognition, which peaked at 14 d with a 4.3-fold increase compared to controls. Conversely, the low-susceptibility strain mounted rapid immune defences with FREP2 (fibrinogen-related protein) and Cu-Zn_SOD1 (antioxidant enzyme) increasing 8.2- and 6.5-fold, respectively, within 72 h post-infection (Figure 5B). Early-phase upregulation of Galectin (3.8-fold) and HSP70 (2.9-fold) further distinguished low-susceptibility strains, suggesting enhanced pathogen surveillance and stress tolerance.

Figure 5. Immune gene dynamics in Physa acuta. (A) The high-susceptible strain (Zhaoqing-P0). (B) The low-susceptibility strain (Qingyuan-F1). SOD, superoxide dismutase; HSP, heat shock protein; FREP, fibrinogen-related protein; TEP, thioester-containing protein; GST, glutathione s-transferase; MIF, macrophage migration inhibitory factor; LRP, leucine-rich protein.

Notably, oxidative stress markers (Fe-Mn_SOD2, GST) remained suppressed in susceptible snails throughout the infection, while the low-susceptibility strains downregulated these genes after initial activation. By day 21, the transcriptional profiles of low-susceptibility snails returned to baseline, while susceptible individuals exhibited chronic immune dysregulation (MIF, LRP remained persistently elevated). These dynamics highlight a critical period (1–3 days post-infection), during which differences in infection outcomes among P. acuta strains were evident.

Discussion

The global spread of A. cantonensis underscores the critical role of intermediate snail hosts in shaping transmission dynamics, particularly in rapidly urbanizing regions like southern China (Cowie, Reference Cowie2017; Turck et al., Reference Turck, Fox and Cowie2022; Anettova et al., Reference Anettova, Sipkova, Balaz, Hambal, Coufal, Kacmarikova, Vanda, Eka and Modry2025; Jones et al., Reference Jones, Nemeth, Piersma, Hardman, Shender, Boughton, Garrett, Castleberry, Deitschel, Teo, Radisic, Dalton and Yabsley2025; Rodriguez-Morales et al., Reference Rodriguez-Morales, Shehata, Parvin, Tasnim, Duarte and Basiouni2025). The parasite undergoes key developmental stages within its intermediate host to become infective third-stage larvae (L3) (Griffin et al., Reference Griffin, Ezenwa and Cowie2025). Unlike Schistosoma mansoni and Schistosoma japonicum (Sun et al., Reference Sun, Hong, Ding, Wu and Lin2024), A. cantonensis exhibits a much broader host preference among intermediate snail hosts (Xu et al., Reference Xu, Xu, Sun, Xu, Zeng, Shan, Yuan, He, He, Yang, Luo, Wei, Wu, Liu, XU, Dong, Song, Zhang, Yu, Wang, Zhang, Fang, Gao, Lv and Wu2019; Jaume-Ramis et al., Reference Jaume-Ramis, Martinez-Orti, Delgado-Serra, Bargues, Mas-Coma, Foronda and Paredes-Esquivel2023). In this study, we revealed that 2 invasive snail species, B. straminea and P. acuta, display different strategies in their interactions with this parasite, with significant implications for disease ecology and control. Biomphalaria straminea from Guangdong Province, China showed near-universal susceptibility to A. cantonensis, with L3 larvae load exceeding 700 larvae per snail, indicating that B. straminea can support a higher larvae load of A. cantonensis larvae relative to its body size, highlighting its suitability as a host for this parasite. While absolute L3 counts were lower than those observed in B. glabrata (up to 2500 larvae per snail), the smaller body size of B. straminea indicates a higher infection intensity relative to body mass. Our findings position B. straminea as a highly susceptible host for A. cantonensis with the capacity to support a relatively high larval load, while P. acuta displays a different pattern of infection intensity.

In contrast, P. acuta populations exhibited some geographic variation in susceptibility to A. cantonensis. Wild strains from Qingyuan retained low larval loads (7.8 ± 2.1 L3/snail) even under high exposure doses, and the F1 and F2 generations also displayed relatively low susceptibility through selective breeding. The expression profiling traced this resistance to the rapid deployment of pathogen recognition (FREP2, Galectin) and antioxidant (Cu-Zn_SOD1) defences within 72 h post-infection, which may be associated with a diminished or delayed response in susceptible strains. Previous studies have shown that SOD can increase antioxidant activity in response to oxidative stress during A. cantonensis infection (Xu et al., Reference Xu, Xu, Sun, Xu, Zeng, Shan, Yuan, He, He, Yang, Luo, Wei, Wu, Liu, XU, Dong, Song, Zhang, Yu, Wang, Zhang, Fang, Gao, Lv and Wu2019). Fibrinogen-related proteins play a crucial role in the immune response of snails, contributing to the compatibility and defence mechanisms against parasitic infections like S. mansoni (Pila et al., Reference Pila, Li, Hambrook, Wu and Hanington2017), and these patterns mirror immune trade-offs observed in schistosome-resistant Biomphalaria, as well as in the A. cantonensis-P. acuta interaction, possibly suggesting conserved evolutionary strategies across snail-parasite systems, though further research is needed.

As larger-sized snail species, P. canaliculata and A. fulica are frequently studied in A. cantonensis research (Villanueva et al., Reference Villanueva, Munoz, Martinez, Cruz, Prieto-Alvarado and Liscano2024; Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Jiang, Fang, Chen, Liu, Zhao, Andrus, Li and Guo2024), but our findings highlight the significant, yet sometimes possibly underappreciated, role of small-bodied invasive snail species in China. While previous studies have catalogued susceptibility differences across snail species (Ibrahim, Reference Ibrahim2007; Song et al., Reference Song, Wang, Yang, Lv and Wu2016; Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Jiang, Fang, Chen, Liu, Zhao, Andrus, Li and Guo2024), the mechanistic basis of intraspecific variation, particularly the heritable resistance observed in P. acuta, has remained unexplored. Similar to the mechanisms of susceptibility to schistosomes in snails (Coustau et al., Reference Coustau, Gourbal, Duval, Yoshino, Adema and Mitta2015; Gerdol and Venier, Reference Gerdol and Venier2015; Pila et al., Reference Pila, Li, Hambrook, Wu and Hanington2017), the early upregulation of FREP2 and SOD1 in the low-susceptibility strains may provide new insights that could inform strategies for A. cantonensis control by regulating the expression of host-related genes, which warrants further investigation. Coupled with B. straminea’s susceptibility, these insights enable risk stratification, where aquaculture zones invaded by B. straminea require urgent containment, while P. acuta-dominant habitats may benefit from management strategies that leverage natural resistance.

The study highlights the relationship between host-parasite ecology and molecular mechanisms. By identifying the timing of immune changes in P. acuta, we align snail biology with arthropod vector research on TEPs (Eleftherianos and Sachar, Reference Eleftherianos and Sachar2020), in which early responses often dictate infection outcomes. Limitations remain, particularly the need for field validation of larval load thresholds and functional confirmation of candidate genes using CRISPR editing (Henry and Lyons, Reference Henry and Lyons2016; Sun et al., Reference Sun, Hong, Ding, Wu and Lin2024; Accorsi et al., Reference Accorsi, Pardo, Ross, Corbin, Mcclain, Weaver, Delventhal, Gattamraju, Morrison, Mckinney, Mckinney and Sanchez2025). However, the framework established here may offer a blueprint for precision control of snail-borne diseases, prioritizing interventions based on host competence and immune phenotypes.

As urbanization may accelerate human-snail contact (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Zeng, Sanogo, He, Xiang, Du, Zhang, Wang, Wan, Zeng, Yang, Lv, Liang, Deng, Hui, Yuan, Ding, Wu and Sun2020; Glidden et al., Reference Glidden, Singleton, Chamberlin, Tuan, Palasio, Caldeira, Monteiro, Lwiza, Liu, Silva, Athni, Sokolow, Mordecai and De Leo2024; Moreira et al., Reference Moreira, Silva, Gomes, Mattos, Sousa, Silva, Pinto and Thiengo2024), our findings highlight the potential transmission risks of A. cantonensis posed by small-bodied invasive snail species in southern China. Our results show that B. straminea is a competent intermediate host for A. cantonensis, supporting a 100% infection rate in our experiments. Therefore, the invasion of B. straminea suggests the potential presence of disease transmission routes that may threaten human and animal health, necessitating targeted surveillance of snail habitats. On the other hand, the difference in susceptibility between different P. acuta strains may provide a foundation for further understanding the mechanisms of the A. cantonensis-snail interaction. By combining molecular insight with ecosystem-level analysis, this work may demonstrate how mechanistic research can directly inform efforts to mitigate emerging zoonotic diseases.

In this study, we adopted a binomial definition of susceptibility (i.e. infection success based on the presence of at least 1 larva), which confirmed 100% susceptibility in B. straminea. However, had a continuous metric (e.g. distribution of larval load) been used, it would have further emphasized the dose-dependent infection dynamics and individual variation. Furthermore, analysing the results by expressing larval load relative to soft tissue mass (such as larvae per gram) could more accurately reflect physiological tolerance, which is worth discussing. Indeed, our data already indicate that despite its smaller body size, B. straminea harbours a larval load comparable to that of B. glabrata, implying a higher larval load. Therefore, adopting a mass–standardized metric would likely strengthen this observation, underscoring the exceptional suitability of B. straminea as a host for A. cantonensis.

Our study also has some limitations. First, the findings from this study suggest that while lab-based results are promising, field validation is needed to determine how many field-collected snails are infected. Second, the lack of transcriptomic studies prevents us from identifying or further clarifying which genes play a key role in snail resistance to A. cantonensis infection. Third, the absence of replication and analysis of environmental factors limits our ability to account for variations in susceptibility dynamics across different conditions and snail generations. Future research could focus on mapping larval load thresholds in Guangdong’s interconnected habitats and testing CRISPR-edited P. acuta lines to explore the roles of specific genes in resistance.

This study reveals that B. straminea in Guangdong shows a high susceptibility to A. cantonensis, making it a valuable model for laboratory studies, although its role in natural transmission is not fully understood. Geographic strains of P. acuta display varying susceptibility to A. cantonensis, suggesting that immune mechanisms are involved in the host-parasite interactions. Immune defences, including pattern recognition proteins and oxidative stress-related proteins, appear to be linked to the susceptibility of P. acuta. These findings offer important biological insights and enhance our understanding of the interactions between snails and A. cantonensis.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182025101455

Data availability statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author contribution

DTL, XS, SL and ZDW conceived and designed the study. PH and DTL prepared the manuscript, handled the statistical analysis and interpreted the data. PH, KFJ and DTL carried out the experiments. PH, BS and DTL performed field investigations. PH, JK, PYP, WXW, DG and DTL critically revised the draft version of the paper.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Key R&D Program of Guangdong Province (No. 2022B1111030002), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 82202560, 82161160343 and 82272361), the Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangdong Province (No. 2021B1212040017), the Tibet Natural Science Foundation (No. XZ202401ZR0017), the Natural Science Basic Research Program of Shaanxi Province (No. 2023-JC-YB-792), Youth S&T Talent Support Programme of Guangdong Provincial Association for Science and Technology (No. SKXRC2025159), the National Key R&D Program of China (Nos. 2024YFC2309700, 2020YFC1200100 and 2016YFC1200500), the Science and Technology Projects in Guangzhou (No. 2024A04J4314), and the 111 Project (No. B12003).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical standards

Not applicable.