Background

Longevity and healthy ageing have become major focal points in public health and biomedical research. This is primarily driven by the growing population of individuals aged 65 and older, combined with a global decline in birth rates. Moreover, in recent decades, the number of people reaching 100 years or more (centenarians) has steadily risen. This is primarily attributable to the advancements in public health, medicine and healthcare access, alongside stabilised political, social and economic systems in most countries(Reference Vaupel, Villavicencio and Bergeron-Boucher1).

The phenomenon of extreme life expectancy has provoked research interest in the factors contributing to long-lived, disease-free years. Being a centenarian is still rare, as they only make up 0.06% of the population(Reference Buchholz2). They live long lives and, for most years, are physically sound and independent(Reference Andersen, Sebastiani and Dworkis3–Reference Zhang, Murata and Schmidt-Mende5). For this vital aspect, observational studies have suggested that centenarians either escape, delay or survive common chronic diseases(Reference Ailshire, Beltrán-Sánchez and Crimmins4,Reference Zhang, Murata and Schmidt-Mende5) , reflecting a scenario of low disease prevalence and functional independence well into their 90s(Reference Ailshire, Beltrán-Sánchez and Crimmins4,Reference Kheirbek, Fokar and Balish6) . This evidence is valuable in guiding research to identify key modifiable factors contributing to longevity. Extending healthy ageing enhances the quality of life for older individuals and their caregivers while boosting productivity and alleviating government spending on healthcare and social services.

Numerous factors influence healthy longevity. Environmental factors have been suggested to contribute to a long life of over 60%, while genetics accounts for roughly 30% in previous observational studies(Reference Nickols-Richardson, Johnson and Poon7). This statistic not only highlights the likelihood of living long but also inspires many people who desire to do so, especially if we can identify feasible lifestyle interventions. A person-centred and cost-effective strategy would be largely beneficial in negating the negative impacts of population ageing.

Eating is one of the most fundamental lifestyle and health practices that people can change. In some cases, diet may be more effective than exercise in slowing down the biological ageing process. In a randomised controlled trial (RCT) of obese adults 65 or over in the USA, results of the secondary analysis(Reference Ho8) suggests that both the diet alone (lower- energy intake balanced diets) and combining diet (lower-energy intake balanced diets) and exercise (weekly exercise including aerobic, resistance and balanced workout for 90 min) groups significantly reduced biological ageing in years than the groups of exercise alone and controls at 12 months (− 2.4 ± 0.4, − 2.2 ± 0.3, − 0.2 ± 0.4 and 0.2 ± 0.5, respectively). However, only the combined diet and exercise group significantly reduced the healthy ageing index, which included five physiological functions: systolic blood pressure, creatinine, fasting glucose, Modified Mini-Mental Status Examination score and VO2 max, a measure of cardiopulmonary function. This was the first trial comparing diet and exercise on biological ageing that demonstrated the pivotal role of diet in delaying biological ageing in older obese adults. While diet and exercise are both critical to promoting healthspan, the evidence suggests that nutrition serves as the primary foundation. This may be particularly important for older adults with chronic pain, mobility limitations or multimorbidity(Reference Dong, Mather and Brodaty9).

In the spirit of transforming the concept of food as medicine into practical daily habits to empower people to live healthy, long lives, this review aimed to use empirical evidence to demonstrate the critical role of food and nutrition in the prevention and management of diseases that are highly prevalent in older age. This was followed by a review of diet and nutrition concerning healthy longevity and the relevant mechanisms. By doing so, this paper hoped to achieve two primary purposes: (1) to increase awareness, understanding, acceptance and adoption of choosing the right foods to enhance wellness in self-management and clinical practice and (2) to call on future research directions and collaborations, emphasising the intersection of nutrition and healthspan to identify culturally tailored, person-centred dietary approaches.

Analysis framework

This review was organised using a problem-solving framework that addresses three key questions. First, ‘What?’ It examined the evidence linking food and nutrition to metabolic health, cognitive function, musculoskeletal health and dietary habits observed in centenarians. Second, ‘Why?’ It explored the underlying mechanisms through which diet and nutrition influence biological aging and ageing markers. Finally, ‘How?’ It proposed a person-centred, practical dietary approach to promote healthy ageing across diverse cultural contexts, aiming to identify sustainable, culturally appropriate diets supporting health and longevity.

Motivation

Food as medicine

The concept of ‘food as medicine’ dates back to 460–370 BCE and is often attributed to the Greek philosopher Hippocrates, who advocated for natural remedies and balanced nutrition in disease prevention and management(Reference Smith10). Traditional medicine systems, such as Traditional Chinese Medicine from China and Ayurveda (an alternative medicine system) from India, have also recognised food as central to health for thousands of years(Reference Marcus and Marcus11,Reference Subhose, Srinivas and Narayana12) , emphasising the balance of food and herbs to maintain well-being and treat ailments.

In modern public health, dietary guidelines established by government health authorities provide recommendations for nutrient intake to support physiological needs, maintain energy balance and promote overall health. However, achieving optimal nutrient intake and adhering to these recommendations remains a widespread challenge. Common barriers include financial constraints, lack of motivation, time limitations, cultural norms, familial eating habits, social support and prevailing dietary patterns(Reference Mostafavi-Darani, Zamani-Alavijeh and Mahaki13,Reference Domosławska-Żylińska, Łopatek and Krysińska-Pisarek14) . While addressing these challenges is beyond the scope of this review, it is important to recognise that they need to be mitigated through a multifaceted approach, including individual behaviour change, family and community engagement and policy implementation.

Drawing on a comprehensive review of observational and intervention studies across diverse populations, this review highlights the concept of ‘food as medicine’ as a fundamental principle in preventing and managing chronic diseases, while promoting healthy longevity.

Analysis

What is the evidence of diet/nutrition, disease and healthy longevity?

Chronic diseases in older adults, such as cardiovascular issues, dementia and musculoskeletal disorders, are strongly linked to poor dietary habits like low consumption of whole grains, fruits and vegetables. In contrast, healthy dietary patterns such as the Mediterranean diet, the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet and plant-based diets, which emphasise fibre-rich foods, have been shown to reduce these risks and improve outcomes by modulating weight, blood pressure, inflammation and cognitive and musculoskeletal health.

Diet and nutrition in chronic disease

While age does not necessarily contribute to all health conditions, ageing in older age, such as 65 or over, suggests cellular and molecular damage leading to declines in systemic function(15,Reference Li, Wang and Jigeer16) . The burden of disease in older age has been relatively consistent over the past decades, with the top conditions including ischaemic heart disease, stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, cancers and musculoskeletal disorders(Reference Collaborators17,Reference Prince, Wu and Guo18) .

Diet plays a crucial role in disease prevention and management as we age(Reference Cano-Ibáñez and Bueno-Cavanillas19,Reference Roberts, Silver and Das20) . Several systematic reviews have provided evidence to support this point. In the 2017 Global Burden of Disease Study, including 195 countries in 1990–2017, dietary risk factors, including high sodium intake and low intake of whole grains and fruits, were identified as leading risk factors contributing to 11 million deaths and 255 million disability-adjusted life years globally(21). In a systematic review of primarily observational studies and a few clinical trials, the Mediterranean diet, featuring the consumption of olive oil, nuts and vegetables and a modest intake of fish and poultry, was suggested to reduce the risk of dementia, frailty and other musculoskeletal disorders in older people aged 65 or over(Reference Fekete, Varga and Ungvari22–Reference Dominguez, Donat-Vargas and Sayon-Orea26). Other studies have also highlighted dietary risks, including low consumption of whole grains, fruit and vegetables and nuts and legumes and high sodium intake and high red or processed meat intake, contributing to overall mortality and global burden of disease(Reference Ezzati and Riboli27), cardiovascular diseases(Reference Pörschmann, Meier and Lorkowski28,Reference Meier, Gräfe and Senn29) and deaths due to cardiometabolic conditions(Reference Micha, Peñalvo and Cudhea30).

Upon closer examination, the key dietary factors associated with mitigating health risks include a higher intake of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, nuts and legumes, along with moderate sodium intake and limited or no consumption of red or processed meats. These can then be summarised as high fibre-rich food intake, a diet primarily close to the Mediterranean diet, the DASH diet(Reference Chiavaroli, Viguiliouk and Nishi31,Reference Saneei, Salehi-Abargouei and Esmaillzadeh32) or a plant-based diet(Reference Wang, Li and Li33).

Dietary patterns and health benefits

A healthy dietary pattern is typically characterised by higher consumption of whole grains, fruits, vegetables, legumes, nuts and lean protein sources, such as fish and poultry. Additionally, it includes moderate consumption of red and processed meat, salt and added sugars(Reference English, Raghavan and Obbagy34,Reference Dominguez, Veronese and Baiamonte35) . These characteristics align with evidence-based healthy dietary patterns, such as the Mediterranean diet, the DASH diet, the MIND (Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay) diet and plant-based diets, all of which have been consistently linked to a lower risk of chronic diseases and all-cause mortality across various populations(Reference English, Ard and Bailey36).

Numerous systematic reviews have demonstrated that adherence to these dietary patterns is associated with reduced risks of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes and cognitive decline(Reference Martínez-González, Gea and Ruiz-Canela37–Reference Féart, Samieri and Rondeau39). The DASH diet has effectively reduced hypertension and improved metabolic health(Reference Chiavaroli, Viguiliouk and Nishi31,Reference Saneei, Salehi-Abargouei and Esmaillzadeh32,Reference Hinderliter, Babyak and Sherwood40) . Similarly, adherence to the Mediterranean diet has been associated with a lower risk of Alzheimer’s disease and slower cognitive decline(Reference Féart, Samieri and Rondeau39,Reference Hatab, Sam and Beshir41) . The MIND diet, which combines elements of the Mediterranean and DASH diets, has demonstrated strong neuroprotective associations(Reference Morris, Tangney and Wang42).

For musculoskeletal health, a balanced diet that emphasises nutrient-dense foods, such as fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts and low-fat dairy, has been linked to improved bone mineral density and lower fracture risk(Reference Boushey, Ard and Bazzano43,Reference Noori, Jayedi and Khan44) . Moreover, evidence suggests that plant-based diets and healthy dietary patterns may have protective effects against knee osteoarthritis-related pain and structural decline(Reference Dai45,Reference Buck, Vincent and Newman46) .

Although the evidence supporting these dietary patterns is robust in the general older population, studies examining their impact on centenarians and near-centenarians remain limited. Available data suggest that individuals with extreme longevity tend to consume balanced, diverse diets with macronutrient ratios favouring carbohydrates from whole food sources, moderate protein intake primarily from plant-based and lean animal sources and healthy fats. Such dietary habits may contribute to the lower prevalence of chronic diseases and reduced medication use among centenarians(Reference Dai, Lee and Sharma47).

By contrast, diets high in ultra-processed foods, which typically contain high amounts of salt and sugar, have been linked to increased risks of cardiometabolic diseases and mortality. Most evidence was rated as low or very low in an umbrella review of 45 pooled analyses involving over 9 million participants(Reference Lane, Gamage and Du48). To date, various definitions of ultra-processed foods have been proposed(Reference Gibney49). In this review, ultra-processed foods are referred to as food products that undergo multiple stages of industrial physical and chemical processing to create hyper-palatable food and beverage items(Reference Monteiro, Cannon and Levy50). These foods often contain artificial flavours, colours, emulsifiers and a wide array of additives designed to enhance taste, texture and shelf life, rather than nutritional value. In large prospective cohorts in the USA and Europe with long follow-up, the intake of ultra-processed food was associated with an increased risk of mortality. However, the magnitude of the effect varies among studies(Reference Lane, Gamage and Du48,Reference Schnabel, Kesse-Guyot and Allès51,Reference Fang, Rossato and Hang52) .

Finally, the relationship between red or processed meat consumption and mortality is inconsistent(Reference Pan, Sun and Bernstein53–Reference Iqbal, Dehghan and Mente56). It is worth noting that this line of research presents challenges to conducting a clinical trial due to ethical considerations. At the same time, cohort observational studies are usually considered to lack the rigour to prove causality. Most health guidelines recommend limiting the consumption of red and processed meats to moderate levels.

Dietary fibre and overall health benefits

Dietary fibre is primarily obtained from whole grains, fruits, vegetables, nuts and legumes(Reference Dhingra, Michael and Rajput57). Its health benefits stem from multiple mechanisms, including its ability to trap sugars and fats in the upper gastrointestinal tract(Reference Abdolghaffari, Farzaei, Lashgari, Nabavi, D’Onofrio and Nabavi58) and its prebiotic function. These functions are primarily associated with soluble fibre(Reference McKeown, Fahey and Slavin59). The latter is likely to promote beneficial gut microbiota, enhance immune function and reduce inflammation and infection risks(Reference Abdolghaffari, Farzaei, Lashgari, Nabavi, D’Onofrio and Nabavi58,Reference Donini, Savina and Cannella60) . Insoluble fibre is another type of fibre that promotes regularity and prevents constipation(Reference McKeown, Fahey and Slavin59). Both types of fibres are health beneficial, and fibre-rich foods mentioned above often include both fibre types.

In older adults, sufficient fibre intake becomes particularly important due to age-related dietary changes, altered gastrointestinal function and shifts in microbiota composition(Reference Abdolghaffari, Farzaei, Lashgari, Nabavi, D’Onofrio and Nabavi58). Adequate fibre consumption fosters gut microbial diversity, increasing beneficial microbes while suppressing harmful anaerobes and clostridia(Reference Abdolghaffari, Farzaei, Lashgari, Nabavi, D’Onofrio and Nabavi58,Reference Donini, Savina and Cannella60,Reference Norton, Lovegrove and Tindall61) . Although data are scarce, limited intervention studies have suggested that fibre alleviates common gastrointestinal issues such as constipation, diarrhoea and inflammatory bowel disease, while also improving the bioavailability of essential nutrients, lipid metabolism and glycaemic control(Reference Dror62).

Beyond the health benefits for the digestive system, fibre intake has been widely associated with a reduced risk of chronic diseases. Systematic reviews indicate that a high-fibre diet lowers the risk of cardiovascular disease(Reference Threapleton, Greenwood and Evans63), type 2 diabetes(Reference Reynolds64,Reference Montonen, Knekt and Järvinen65) and all-cause mortality(Reference Kim and Je66). Clinical trials further highlight fibre’s benefits, showing reductions in body weight(Reference Slavin67,Reference Grube, Chong and Lau68) , blood pressure(Reference Evans, Greenwood and Threapleton69) and circulating C-reactive protein (CRP)(Reference Jiao, Xu and Zhang70), along with improvements in glycaemic control(Reference Anderson, Baird and Davis71,Reference Silva, Kramer and de Almeida72) .

Dietary fibre and cognitive function

Fibre intake has been linked to cognitive health. A study of elderly French women found that low soluble fibre intake contributed significantly to cognitive impairment(Reference Vercambre, Boutron-Ruault and Ritchie73). A double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover RCT demonstrated that oligofructose-inulin supplementation improved well-being, mood and cognitive performance, particularly in recognition memory and episodic recall(Reference Smith, Sutherland and Hewlett74). Additionally, findings from the Health and Retirement Study(Reference McEvoy, Guyer and Langa75) and the 2015 US Memory and Aging Project(Reference Morris, Tangney and Wang42) suggest a dose-dependent association between high-fibre diets, such as the Mediterranean and MIND diets, and better cognitive function and a lower risk of dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease.

Dietary fibre and musculoskeletal health

Emerging evidence also supports fibre’s role in musculoskeletal health. Epidemiological studies indicate that dietary fibre from whole grains, fruits, vegetables and nuts is associated with a lower trajectory of knee osteoarthritis pain over 10 years, as observed in the Osteoarthritis Initiative(Reference Dai, Lu and Niu76). Additionally, higher fibre intake was linked to a reduced risk of developing painful knee osteoarthritis in both the Osteoarthritis Initiative and the Framingham Heart Study(Reference Dai, Niu and Zhang77). Causal inference analyses using mediation analysis suggest that fibre may protect joint health by influencing body mass and potentially lowering systemic inflammation, particularly CRP levels(Reference Dai, Jafarzadeh and Niu78). Furthermore, findings from the Framingham Heart Study indicate that increased fibre consumption may support bone mineral density in older men over time(Reference Dai, Zhang and Lu79).

This line of evidence underscores the multifaceted role of dietary fibre in reducing the risk of common disease burdens. From enhancing gut health and lowering inflammation to protecting cognitive and musculoskeletal functions, fibre is a crucial component of a longevity-promoting diet. Its benefits extend across multiple systems, highlighting its importance in maintaining overall well-being as individuals age. However, meeting the recommended dietary fibre intake of 25–30 g/d at the population level remains a key public health priority(Reference McKeown, Fahey and Slavin59).

Diet and nutrition in centenarians and near-centenarians

Centenarians (aged 100 or above) and near-centenarians (those aged 95–99) represent a remarkable ageing phenomenon, reflected by living mostly disease-free years during long life expectancy(21,Reference Willcox, Willcox and Poon80) . Two longitudinal cohorts from the USA and Sweden demonstrated that centenarians, compared to other older age groups within the same birth cohort, had lower disease prevalence, lower physical disability and higher cognitive function(Reference Ailshire, Beltrán-Sánchez and Crimmins4,Reference Zhang, Murata and Schmidt-Mende5) . Specifically, the Health Retirement Study in the USA reported that centenarians were generally healthier throughout their 80s and 90s than their shorter-lived cohort counterparts. However, half of them experienced or survived from hypertension, diabetes, cancers, chronic lung diseases, heart disease and stroke, while the rest exhibited healthy ageing by either escaping or delaying disease and functional impairment(Reference Ailshire, Beltrán-Sánchez and Crimmins4). Regarding disability and cognitive impairment, most centenarians postponed physical and cognitive impairment into their 90s(Reference Ailshire, Beltrán-Sánchez and Crimmins4). Similarly, centenarians in the Stockholm study showed lower incidence rates of stroke, myocardial infarction, cancer and hip fracture compared to other age groups who died in their 60s, 70s, 80s or 90s, and there was a lower lifetime risk represented by cumulative incidence for all the above-mentioned conditions except for a slightly higher rate of hip fractures. These two studies have provided strong epidemiological evidence to support the fact that centenarians tend to have delayed disease onset and live mostly disease-free years in their life course(Reference Zhang, Murata and Schmidt-Mende5).

To date, only two published reviews have provided an in-depth exploration of diet and nutrition among centenarians. In a narrative review by Hausman and colleagues(Reference Hausman, Fischer and Johnson81), several studies were selected to examine centenarians’ dietary habits, focusing on BMI, antioxidant vitamins, B vitamins and serum 25(OH) vitamin D in centenarians in Japan, Georgia, the USA and Sicily in Italy. The summarised results indicate a low BMI in centenarians and insufficient levels of antioxidants, vitamins A and C, and B vitamins, suggesting suboptimal nutrition in this demographic.

However, when reviewing the dietary habits of centenarians in Japanese and US studies, common food groups showed high consumption of fruits and vegetables, while total energy intake and protein intake tended to be lower than those in other non-centenarian age groups(Reference Hausman, Fischer and Johnson81). In the Georgia study in the USA, food access was a problem in community-dwelling centenarians(Reference Johnson, Davey and Hausman82). However, another comprehensive systematic review led by Dai and colleagues, published in 2024(Reference Dai, Lee and Sharma47), highlights macronutrient-balanced, diverse dietary components and moderate salt intake from 34 observational studies conducted among various countries between 2012 and 2022. This review suggests that centenarians typically consume a balanced and diverse diet, with 60% (range: 57–65%) of their energy intake from carbohydrates, 19% (12–32%) from protein and 29% (27–31%) from fat, and their diets tended to have high diet diversity score; protein sources were primarily from poultry, fish and legumes; intakes of salty foods, sweets and saturated fats were not common. It is worth noting that the pooled analysis indicates that centenarians consistently have a normal range of total cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol and albumin levels. The review also found that the number of medications tended to be lower than the average of older adults, with a mean of less than five medications among the cohorts assessed. Due to the high heterogeneity of the analyses, no meta-analysis was conducted on the relationship between diet/nutrition and ageing outcomes, however.

Taking these studies together, it is reasonable to conclude that a low nutritional risk is associated with improved longevity. For example, the dietary diversity score was associated with a lower mortality risk, and high salt intake was associated with increased disability in activities of daily living (ADL). In contrast, good dietary habits, such as those with diverse food variety emphasising plant-based foods, were related to lowering ADL disability in the 2024 systematic review(Reference Dai, Lee and Sharma47).

It is worth noting that, compared to other older populations, fewer primary studies have assessed diet and nutrition among centenarians and near-centenarians(Reference Li, Wang and Jigeer16,Reference Dai, Lee and Sharma47,Reference Franceschi, Ostan and Santoro83) . However, all these studies highlight the common dietary components that centenarians consume, including complex carbohydrates, fresh fruits and vegetables, legumes, fish, dairy products and moderate consumption of meat. Whether it is a Mediterranean diet, the Japanese diet among Okinawan centenarians (also known as the Okinawan diet; Okinawa is an island at the southern end of Japan, known for longevity) or healthy diets from other countries, centenarians tend to consume plain food with moderate sodium intake and a diverse variety of food groups. For the latter, a higher dietary diversity score was associated with at least 20% higher odds of becoming a centenarian in the Chinese Longevity and Ageing Study(Reference Lv, Kraus and Gao84).

Since most centenarians tend to live either independently or with others rather than in nursing facilities(Reference Dai, Lee and Sharma47), it is reasonable to conclude that their food choices are often shaped by their living arrangements, social support networks and institutional contexts. Therefore, promoting access to diverse, nutritious and culturally appropriate meals, particularly within care facilities and community-based programmes, could be a vital strategy for supporting healthy longevity.

Caloric restriction

Caloric restriction in this review refers to an average daily energy intake below that of a typical or habitual diet, without malnutrition or deprivation of essential nutrients(Reference Tunay, Franck and Ndeye Coumba85). This differs from a fasting diet in that a person does not eat at all or skips meals during a specific period of time or only consumes food within a specific time block, such as intermittent fasting(Reference Varady86). In fruit flies and rodent models, caloric restriction has been shown to extend life expectancy and longevity(Reference Balasubramanian, Howell and Anderson87,Reference Masoro88) .

It is unclear whether centenarians practised caloric restriction consciously or subconsciously. Some authors have speculated that this may be the case for centenarians, who maintain regular dietary and healthy lifestyle habits with consistent mealtimes to regulate their energy intake(Reference Franceschi, Ostan and Santoro83). Additionally, analysis of centenarians’ nutritional habits revealed that centenarians typically consume high amounts of plant-based foods, leading to natural caloric restriction(Reference Dakic, Jevdjovic and Vujovic89). When the authors compared different biomarkers between non-centenarians who practised dietary restrictions and centenarians who were on usual dietary habits, they found that most metrics such as glucose metabolism, blood pressure, thyroid, lipid profiles, body composition and other metabolites such as cortisol, adiponectin, leptin and tryptophan were in a normal range concordance, except for lower vitamin D levels and higher levels of inflammatory markers in the centenarian group(Reference Franceschi, Ostan and Santoro83). In addition, analyses of the Okinawan diet suggest that this diet is lower in energy intake, higher in consumption of legumes, has better nutrient profiles and has lower sodium intake than the traditional Japanese diet, extending the hypothesis that caloric restriction may contribute to the higher chance of longevity among Okinawans(Reference Willcox, Willcox and Todoriki90).

The current understanding of caloric restriction in prolonging life generally believes that caloric restriction acts as a mild stressor to promote hermetic responses through autophagy, stress defense mechanisms and survival pathways and to attenuate proinflammatory responses in several signalling pathways related to insulin, the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)/ribosomal S6 (S6) kinase pathway and the glucose signalling Ras protein kinase(Reference Ristow and Schmeisser91,Reference Barzilai, Huffman and Muzumdar92) .

While energy intake is reduced, maintaining adequate nutrition may seem another important mechanism for those with extreme longevity. Another review assessed total energy intake in older adults and identified a reduction of approximately 600–1000 kcal as people age after reaching 65 years(Reference Wakimoto and Block93). However, the reduced energy intake resulted in a deficiency of various macro and micronutrients(Reference Kiani, Dhuli and Donato94–Reference Wadden, Stunkard and Brownell96). The important message from this commentary highlights that nutrient deficiency is a severe problem in many older adults(Reference Wakimoto and Block93). Following this logic, it is highly likely that centenarians naturally have lower-energy intake as part of their dietary practices while consuming a nutrient-dense diet that ensures essential nutrition to sustain their health.

While caloric restriction focuses on the amount of food consumed, similar practices such as intermittent fasting and time-restricted eating focus on the timing of eating. The latter has also been suggested to have potential health benefits for metabolic health in glucose and lipid metabolism(Reference Vasim, Majeed and DeBoer97,Reference Yuan, Wang and Yang98) . However, long-term practice and adverse events associated with these dieting practices should be approached with caution, including unintended increases in cardiovascular-related deaths(Reference Harris99), bone loss and lowered immunity(Reference Habib, Ali and Nazir95).

Why? Mechanisms that attribute healthy eating to enhance healthy longevity

Building on this body of evidence, the following section delves into the underlying biological mechanisms by which a healthy diet may mediate these protective effects. Specifically, it explores how nutrient-sensing pathways, such as adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK), target of the rapamycin (TOR) and nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), are activated by healthy eating practices, thereby promoting anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and metabolic responses that contribute to slowing biological ageing and extending healthspan.

Nutrient-sensing mechanisms and healthy ageing

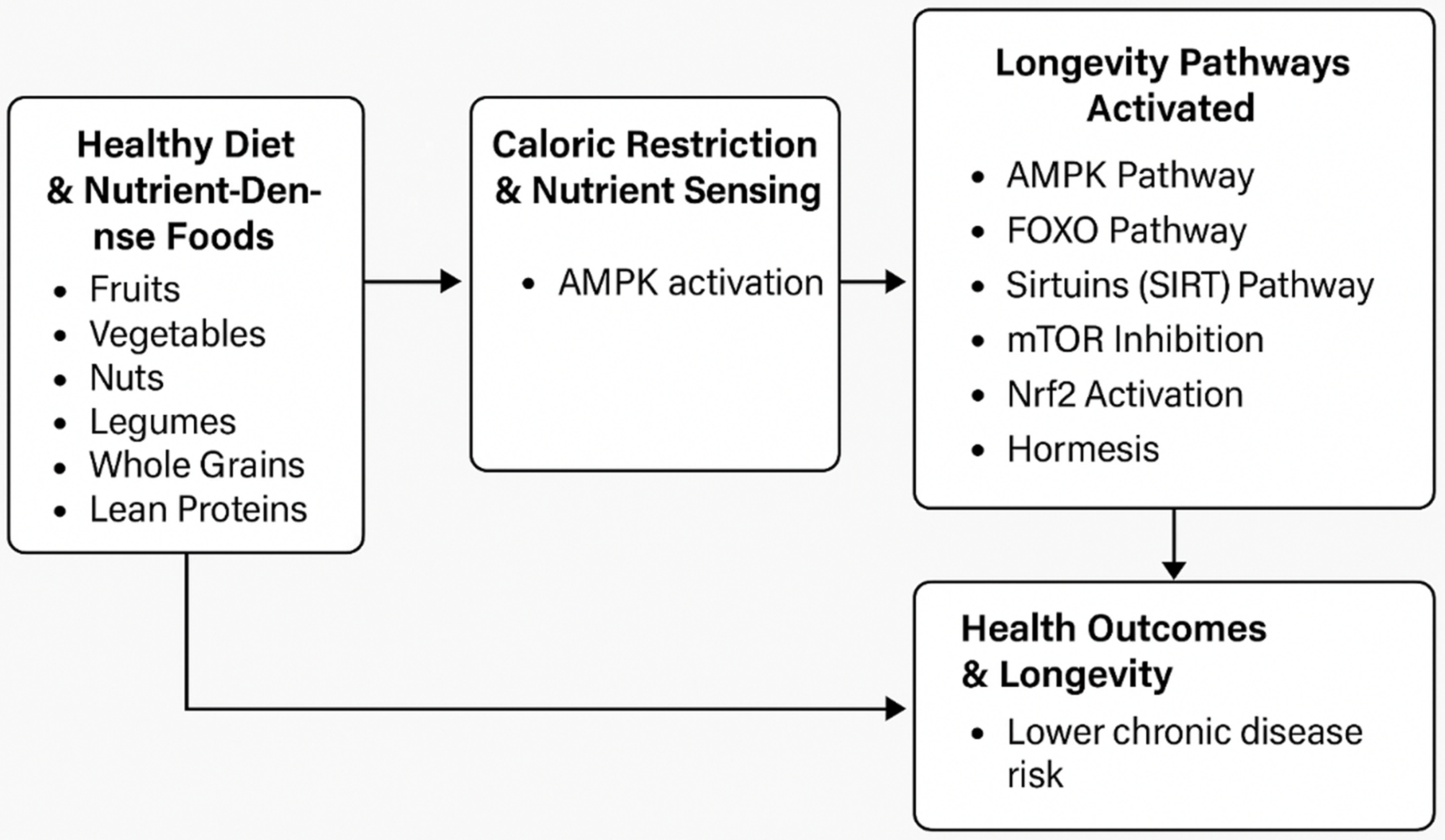

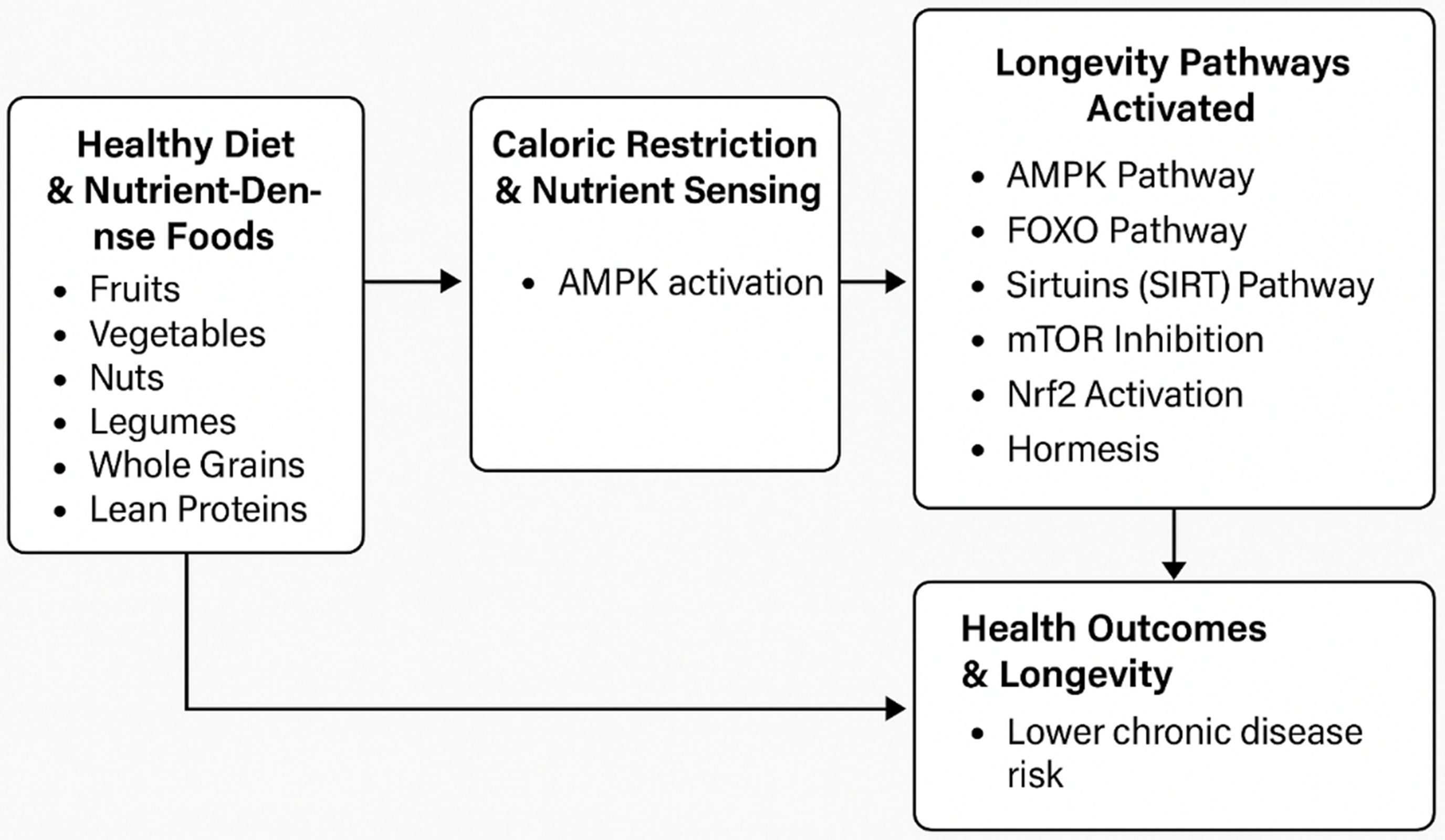

Healthy dietary patterns, particularly those incorporating caloric restriction and nutrient-dense foods, activate key nutrient-sensing mechanisms such as the AMPK, TOR and Nrf2 pathways. These pathways regulate metabolic processes, reduce inflammation and enhance antioxidant responses. Collectively, these mechanisms help mitigate the risk of chronic disease and slow biological aging. This highlights the crucial role of diet and nutrients in extending healthy life spans (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. A conceptual model of how nutrient-dense foods in a healthy diet and caloric restriction activate longevity pathways through the nutrient-sensing mechanisms.

This figure visually illustrates the connection between nutrient-dense foods, caloric restriction and longevity through key biological pathways. These dietary factors, including polyphenols, flavonoids and essential nutrients, activate pathways such as adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK), forkhead box O transcription factors (FOXO), sirtuins, target of the rapamycin (TOR), nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) and hormesis. These pathways regulate energy balance, stress responses and inflammation, reducing disease risk and promoting longevity.

Nutrient-sensing mechanisms and their impact on longevity

Long-term studies have consistently demonstrated that maintaining healthy dietary habits contributes to longevity. Nutrient sensing is a key mechanism that explains these effects. While caloric restriction alone may not drive extreme longevity, a diet with moderate energy intake and nutrient-dense foods, such as fruits, vegetables, nuts, legumes, whole grains and lean proteins like fish, provides essential vitamins, minerals, phytochemicals, fibre and polyunsaturated fats. These dietary compounds are associated with reduced oxidation, anti-inflammatory effects and functional benefits, including improved endothelial function, lipid metabolism, insulin sensitivity, gut microbiota balance and gene regulation related to cellular stress(Reference Almoraie and Shatwan100–Reference Corrêa103). Collectively, these effects may help lower the risk of chronic diseases.

Several significant pathways are believed to impact ageing related to caloric restriction. AMPK plays a central role in cellular energy homeostasis, regulating energy balance at both cellular and systemic levels. AMPK is a sensor for nutrient and energy availability, influencing lifespan and reflecting the positive effects of caloric restriction(Reference Long and Zierath104,Reference Hardie105) . Furthermore, research suggests that AMPK activation modulates other pathways, including forkhead box O transcription factors (FOXO), sirtuins and mTOR, all of which mediate the benefits of caloric restriction(Reference Cantó, Jiang and Deshmukh106–Reference Karagöz and Gülçin Sağdıçoğlu Celep108). The FOXO are downstream regulators of the insulin/IGF-1 signalling pathway, playing crucial roles in regulating gene expression to maintain metabolic homeostasis, balance redox status, respond to stress and promote cell growth(Reference Dobson, Ezcurra and Flanagan109). A 60-day high-sugar diet results in FOXO inhibition and persistent epigenetic modifications in a fly model, leading to a shorter lifespan(Reference Jiang, Yan and Feng110). Sirtuins are enzymes with histone deacetylase activity and other proteins(Reference Grabowska, Sikora and Bielak-Zmijewska111). Their catalytic activity depends on nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) and the dynamic changes in NAD+ levels [NAD+ is a coenzyme involved in various metabolic processes, including energy production and DNA repair](Reference Covington and Bajpeyi112). Seven sirtuins found in humans are believed to play a key role in the cell response to reduce oxidative or genotoxic stress(Reference Covington and Bajpeyi112) and as an important pathway to explain the anti-ageing effect of caloric restriction(Reference Zullo, Simone and Grimaldi113). The TOR pathway is present across various species and plays a crucial role in nutrient sensing, regulating lifespan, stress responses and cellular growth(Reference Hardie105,Reference Kapahi, Chen and Rogers114,Reference Evans, Kapahi and Hsueh115) . Additionally, hormesis suggests that mild stressors can have beneficial anti-ageing effects. It has been proposed as a mechanism behind the longevity benefits of caloric restriction in long-lived species(Reference Marques, Markus and Morris116,Reference Blagosklonny117) .

Interestingly, natural compounds found in fruits, vegetables and herbs, such as polyphenols and flavonoids, activate the Nrf2 pathway, leading to a reduction in oxidative damage by decreasing the production of reactive oxygen species(Reference Rudrapal, Khairnar and Khan118,Reference Muscolo, Mariateresa and Giulio119) . Nrf2 activation has also been linked to protection against inflammation by lowering cytokine and chemokine levels and reducing the expression of inflammatory markers such as cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and nitric oxide synthase(Reference Ahmed, Luo and Namani120,Reference Kim, Cha and Surh121) . This suggests that consuming foods that activate the Nrf2 pathway(Reference Fekete, Szarvas and Fazekas-Pongor101) may enhance cellular stress responses and minimise cell damage(Reference Davinelli, Willcox and Scapagnini122) to increase longevity. Figure 1 briefly summarises the conceptual model of how healthy foods affect longevity through the above-mentioned pathways, with AMPK as the central regulator.

Diet and nutrition in slowing biological ageing

Ageing is often associated with cellular and molecular damage, contributing to systemic deterioration. However, centenarians who evade or delay common chronic diseases suggest that chronological age may not always reflect underlying biological ageing processes(Reference Moqri, Herzog and Poganik123,Reference Herzog, Goeminne and Poganik124) .

The concept of biological age, which considers metabolomic, transcriptomic, epigenetic and proteomic markers, has emerged as a more comprehensive measure of ageing than chronological age(Reference Moqri, Herzog and Poganik123). Many centenarians exhibit significantly younger biological age compared to their chronological age. One study found that centenarians with health metrics similar to those who practise caloric restriction had biological ages approximately 8.7 years younger than expected, based on DNA methylation markers(Reference Franceschi, Ostan and Santoro83).

The question remains: can diet slow biological ageing? Current evidence suggests the answer is yes, as diet influences key ageing biomarkers such as telomere length and DNA methylation-based epigenetic age(Reference Amenyah, Ward and Strain125–Reference García-García, Grisotto and Heini127).

Diet, nutrition and telomere length

Telomeres, protective DNA sequences at the ends of chromosomes, naturally shorten with age. This process, known as telomere attrition, is recognised as one of the hallmarks of ageing. Diet and nutrition may play a role in maintaining telomere length, a key indicator of biological ageing. While most studies on this topic have been conducted in animal or cellular models(Reference Paul128), some human studies suggest dietary factors such as fibre intake(Reference Cassidy, De Vivo and Liu129) and multivitamin use(Reference Xu, Parks and DeRoo130) may be associated with longer telomeres.

However, human studies on the relationship between diet quality and telomere length have yielded mixed results. A cross-sectional analysis from the NHANES suggests that a healthy plant-based diet, characterised by whole grains, fruits, vegetables, nuts, legumes, tea, coffee and vegetable oils, is associated with longer telomeres. In contrast, an unhealthy plant-based diet (high in refined grains, sugar-sweetened beverages and desserts) is linked to shorter telomeres(Reference Li, Li and Cheng131). However, the Helsinki Birth Cohort Study found no significant relationship between telomere length and adherence to the Baltic Sea diet (also known as the Nordic diet, with emphasis on locally sourced, sustainable foods that are common in Nordic countries), the Mediterranean diet or the anti-inflammatory diet over a 10-year follow-up(Reference Meinilä, Perälä and Kautiainen132).

A systematic review(Reference Galiè, Canudas and Muralidharan133) suggests that dietary fibre and adherence to the Mediterranean or anti-inflammatory diet may positively impact telomere length. Cross-sectional studies in NHANES(Reference Tucker134) and the Nurses’ Health Study(Reference Cassidy, De Vivo and Liu129) found associations between fibre intake and telomere length. Similarly, adherence to the Mediterranean diet correlated with longer leukocyte telomere length(Reference Crous-Bou, Fung and Prescott135–Reference Leung, Fung and McEvoy137). By contrast, an intervention study showed no significant effect of the Mediterranean diet on telomere shortening compared to a low-fat diet over five years(Reference García-Calzón, Martínez-González and Razquin138). Nevertheless, adherence to an anti-inflammatory diet has been linked to longer telomeres(Reference García-Calzón, Zalba and Ruiz-Canela139,Reference Shivappa, Wirth and Hurley140) . Additionally, a short-term (12-week) intervention in Australia did not observe significant changes in telomere length in response to dietary improvements(Reference Ward, Hill and Buckley141).

Given these inconsistent findings, it remains unclear whether telomere shortening is a direct cause or a byproduct of ageing. Further research is needed to determine whether telomere length is a reliable biomarker of ageing and how diet influences this process. Identifying dietary biomarkers related to cellular functions, such as DNA integrity and methylation, could clarify these relationships.

Diet, nutrition and DNA methylation

DNA methylation, an epigenetic modification involving the transfer of a methyl group onto cytosine, plays a critical role in gene regulation and cellular identity(Reference Field, Robertson and Wang142,Reference Moore, Le and Fan143) . Genetic and environmental factors, including diet and lifestyle, influence DNA methylation and have been linked to disease risk and mortality(Reference Amenyah, Ward and Strain125,Reference Reale, Tagliatesta and Zardo144) . Consequently, DNA methylation is increasingly used as a biomarker of healthy ageing. Biological ageing clocks have been derived based on DNA methylation, other diseases and lifestyle factors(Reference Reale, Tagliatesta and Zardo144).

Observational studies suggest that healthy dietary patterns – particularly the DASH and Mediterranean diets – are consistently associated with slower epigenetic ageing, as measured by DNA methylation(Reference Kresovich, Park and Keller145–Reference Chiu, Hamlat and Zhang147). Epigenetic age, estimated using epigenetic clocks, refers to a biologically derived measure of ageing based on DNA methylation levels at specific CpG sites (CpG sites are regions in the DNA sequence where a cytosine nucleotide is followed by a guanine nucleotide, linked by a phosphate bond)(Reference Kabacik, Lowe and Fransen148). These methylation patterns change systematically with age and can be used to construct mathematical models that estimate biological age(Reference Kabacik, Lowe and Fransen148). Epigenetic clocks may serve as biomarkers, often used in conjunction with clinical and lifestyle data, to assess the biological age of tissues and cells and to predict chronological age, mortality risk and age-related health outcomes(Reference Kabacik, Lowe and Fransen148,Reference Li, Koch and Ideker149) .

Several widely used epigenetic clocks include PhenoAge, GrimAge and DunedinPACE. PhenoAge (measured in units of years) is an epigenetic clock developed to reflect phenotypic ageing by incorporating DNA methylation surrogates of clinical biomarkers (e.g. albumin, C-reactive protein, glucose) that are associated with morbidity and mortality(Reference Li, Koch and Ideker149,Reference Levine, Lu and Quach150) . DunedinPACE (Pace of Aging Computed from the Epigenome) is designed to measure the rate at which an individual is biologically ageing, based on longitudinal data from a birth cohort, and provides a continuous indicator of biological ageing speed rather than a static age estimate (measured in years of physiologic decline per 1 chronologic year)(Reference Li, Koch and Ideker149,Reference Belsky, Caspi and Arseneault151) . GrimAge Acceleration (measured in units of years) is a composite biomarker derived from DNA methylation surrogates of seven plasma proteins and smoking pack-years. It has demonstrated strong predictive power for age-related disease incidence, time to cancer, cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality(Reference Lu, Quach and Wilson152,Reference Lu, Binder and Zhang153) .

The US Sister’s Study found that adherence to the DASH, alternative Mediterranean diet and other healthy dietary patterns slowed GrimAge, while the DASH diet also slowed PhenoAge(Reference Kresovich, Park and Keller145). Findings from the Framingham Heart Study further support this, with higher DASH diet scores inversely associated with DunedinPACE, PhenoAge and GrimAge(Reference Kim, Huan and Joehanes146). Similarly, a cross-sectional study in California found that the Mediterranean diet was strongly linked to decreases in GrimAge(Reference Chiu, Hamlat and Zhang147).

In this review, only a few pathways related to the normal ageing process have been discussed. It should be noted that the hierarchy of normal ageing includes manifestations at the molecular, cellular, physiological and system levels(Reference López-Otín, Blasco and Partridge154,Reference Parkhitko, Filine and Tatar155) , among which are the hallmarks of ageing(Reference López-Otín, Blasco and Partridge154,Reference Parkhitko, Filine and Tatar155) . More research is needed to understand whether and which dietary components interact with each manifestation and can be targeted as an effective intervention that affects multiple ageing markers. The current evidence has highlighted the critical role of diet and specific foods in slowing biological ageing and promoting longevity.

How? Diet and Nutrition in Ageing in the Cultural Contexts

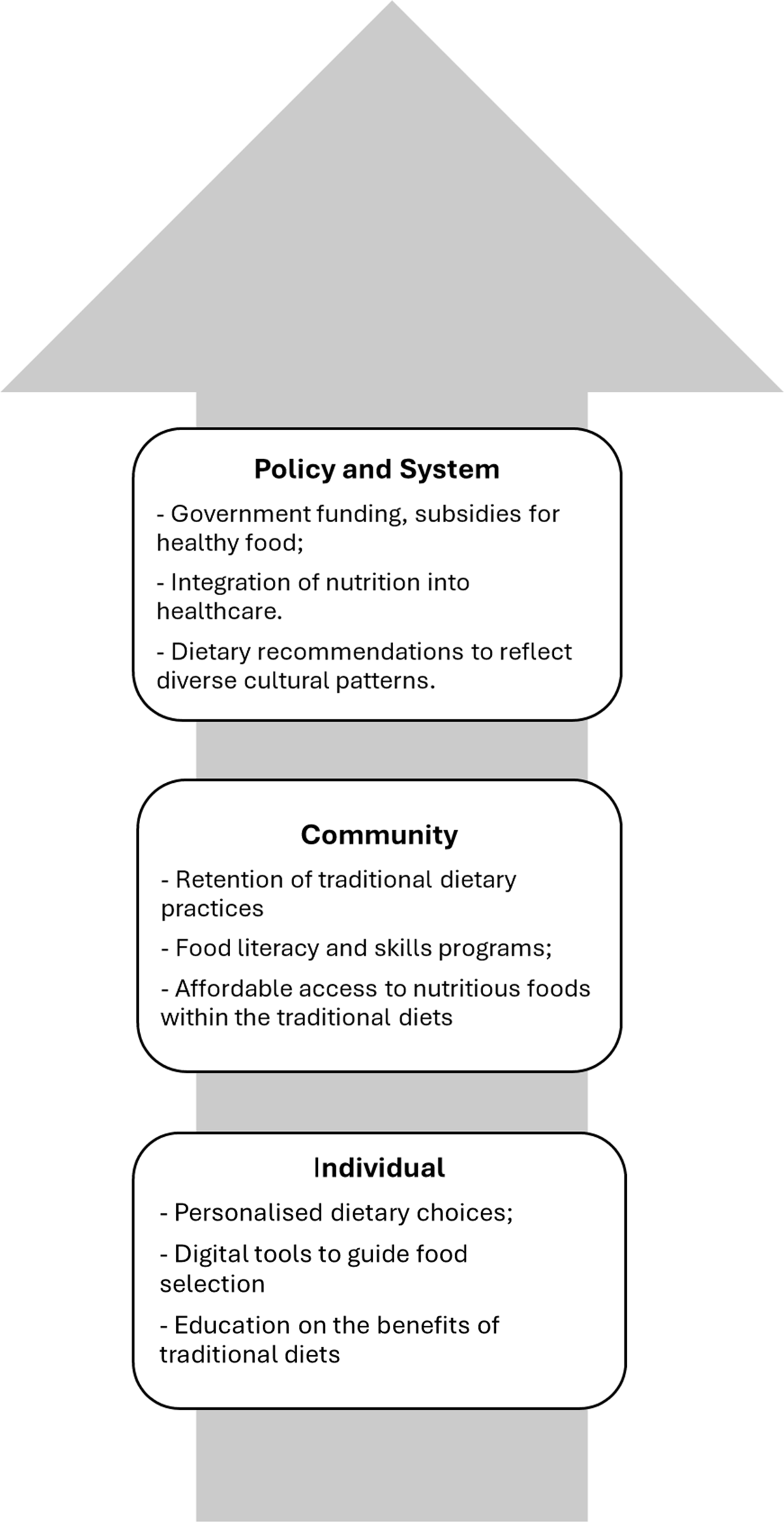

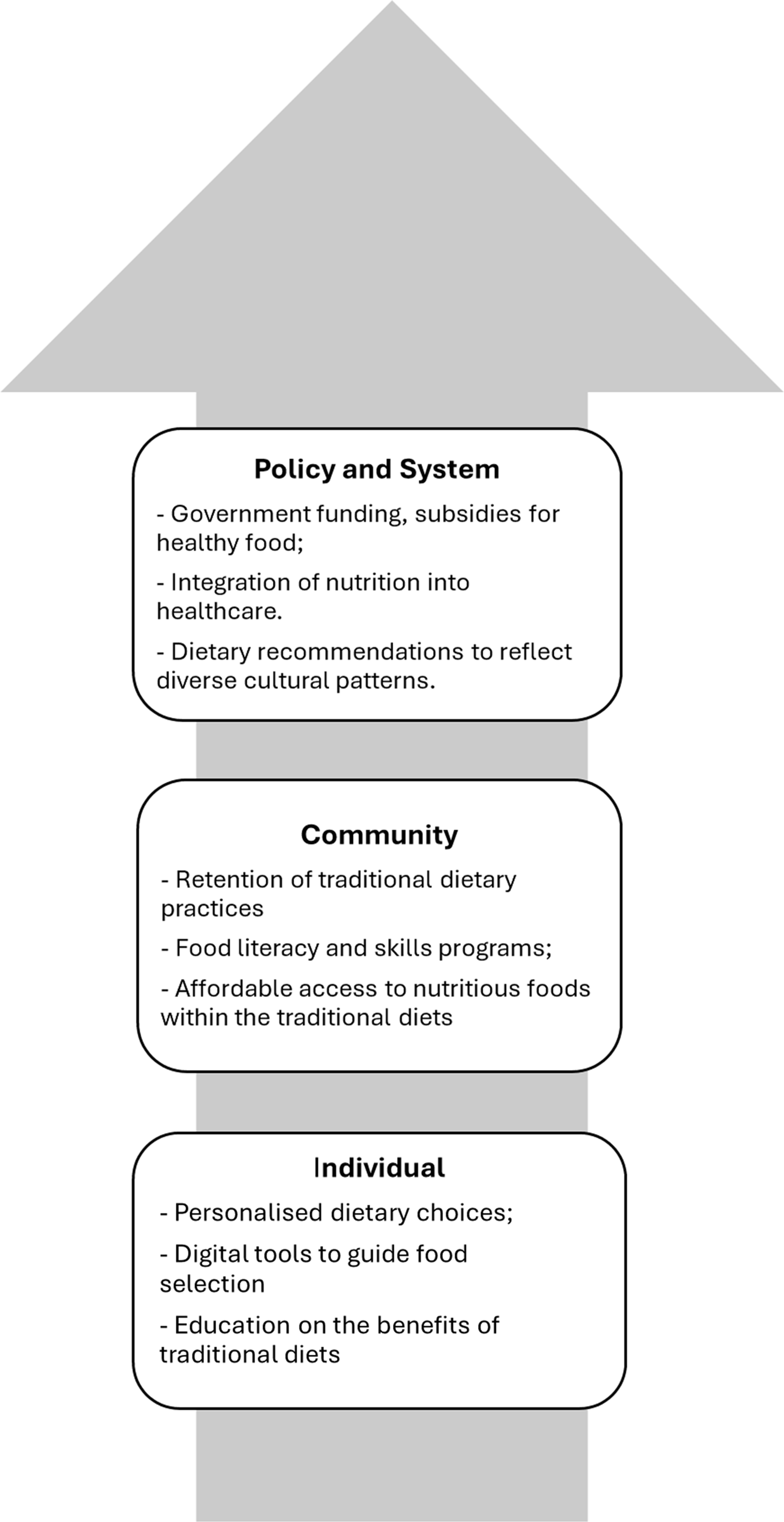

The activation of key nutrient-sensing pathways underscores the biological benefits of healthy eating. However, realising these advantages on a population level requires that dietary recommendations be culturally tailored and aligned with traditional food practices.

Several methods for assessing healthy diets, such as dietary guideline recommendations and diets mentioned in this review, have been associated with or influenced by disease development and ageing biomarkers, along with explanations from biological mechanistic pathways. However, if these diets are not culturally appropriate or aligned with people’s traditional eating habits, promoting food as medicine for healthy ageing becomes mere rhetoric. Hence, dietary interventions must be both culturally and personally adaptable.

Many traditional diets are inherently healthy and diverse. For example, traditional Asian diets, rich in vegetables, soy and fish, share similarities with longevity-promoting patterns in the DASH and Mediterranean diets(Reference Hu156). The Mediterranean nutritional profile is a typical dietary profile followed by centenarians in Sicily, Italy(Reference Vasto, Rizzo and Caruso157). Okinawan centenarians typically consume a low-energy, plant-based diet rich in vegetables, soy products and sweet potatoes, which contributes to lower rates of chronic diseases(Reference Willcox, Scapagnini and Willcox158,Reference Suzuki, Willcox, Willcox and Pachana159) . Similarly, African(Reference LeBlanc, Baer-Sinnott and Lancaster160,Reference Lara-Arevalo, Laar and Chaparro161) and Indigenous(162) diets often emphasise whole grains and legumes for their nutrient density and health benefits. In contrast, Sardinian(Reference Wang, Murgia and Baptista163) and Nicoyan diets(Reference Rosero-Bixby, Dow and Rehkopf164) emphasise plant-based foods, legumes and moderate consumption of animal products to support metabolic and cardiovascular health. This illustrates that when comparing healthy longevity diets, non-Western diets appear to differ from Western diets in their lower consumption of animal protein and dairy foods(Reference LeBlanc, Baer-Sinnott and Lancaster160) due to cultural practice and genetic differences (e.g. high prevalence of lactose intolerance). For the above-mentioned diets, except for DASH, African and Indigenous diets are based on studies of general populations, while others are studies of centenarians.

In modern contexts, access to fresh fruits, vegetables, fish and lean protein can be limited by living environment, cost and seasonal availability. Therefore, increasing financial accessibility through measures such as subsidising healthy food for lower socioeconomic groups is crucial for promoting dietary adherence and adoption. Encouraging the retention of traditional dietary practices and providing culturally appropriate food access is vital, particularly for migrants in new countries, as it helps reduce health disparities, enhances nutritional intake among diverse populations and respects cultural heritage.

Raising awareness of diverse food traditions among the public and healthcare professionals, including primary care providers and dietitians, can strengthen nutrition education, training and prevention strategies. This broader understanding supports a shift from a medicalised model of care towards one that integrates food and nutrition into healthcare delivery, informing food policy, dietary guidelines and government-funded programmes aimed at reducing disease burden and premature mortality.

At the population level, digital tools, if provided access to community members integrated into the healthcare system, may offer transformative potential by enabling the tracking of dietary intake and delivering personalised, evidence-based dietary guidance to support the adoption of long-term healthy eating habits. Policy initiatives and government funding that incentivise healthy food consumption, especially among low-income families and individuals and those living in rural or remote areas with limited access to nutritious foods, can significantly improve diet quality in these underserved populations.

Additionally, promoting food literacy and cooking skills from early childhood to adulthood, including in schools and community centres, can help build healthier communities and societies. These efforts address food and nutrition as foundational, deeply cultural and enjoyable aspects of life. Figure 2 summarises this multi-level approach to developing person-centred, culturally appropriate dietary patterns for population health.

Fig. 2. An example of ways to develop a culturally appropriate healthy diet pattern. This figure illustrates a multi-level approach to developing a culturally appropriate and healthy diet pattern, highlighting key actions at each level.

Conclusion

If they exist, healthy longevity diets tend to share several core characteristics: a strong emphasis on plant-based foods, healthy fats and low to moderate consumption of red and processed meat while limiting the consumption of processed foods, salt and added sugars. Dietary models such as the Mediterranean, DASH and Okinawan diets exemplify these principles, featuring whole grains, fruits, vegetables, legumes and nuts, but vary in specific food choices shaped by cultural traditions. For example, the Mediterranean diet emphasises olive oil, fish and moderate wine consumption, whereas the Okinawan diet is characterised by its low-energy, plant-based approach, featuring root vegetables and soy products.

Growing evidence links these dietary patterns with lower risks of chronic diseases, improved metabolic and cognitive function and enhanced quality of life. As cultural and ethnic backgrounds significantly influence food preferences and metabolic responses, person-centred nutritional strategies – those that tailor recommendations to an individual’s heritage, values and context – are increasingly recognised as essential for promoting healthy ageing.

In conclusion, integrating these evidence-based dietary patterns with personalised nutrition approaches holds promise for preventing age-related diseases and extending both lifespan and longevity. While this review underscores the central role of food as medicine, it also acknowledges that nutrition is just one part of a broader equation. Other lifestyle and social determinants, including physical activity, sleep, social connection and access to healthcare, are also integral to achieving and sustaining healthy longevity.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks the Nutrition Society of Australia for the opportunity to present this work as a speaker at the Healthy Ageing Symposium during the 2024 annual meeting in Sydney, Australia. The author also thanks Professors Perminder S. Sachdev and Karen Charlton for their constructive reviews. Prof. Sachdev is from the Centre for Healthy Brain Ageing, School of Clinical Medicine, Faculty of Medicine and Health, University of New South Wales. Prof. Charlton is from the School of Medical, Indigenous and Health Sciences, Faculty of Science, Medicine and Health at the University of Wollongong. Two consumer representatives (anonymous) also provided reviews based on their lived experiences, including one who is a child of a centenarian.

Financial support

None.

Author contributions

Z.D. conceptualised the talk and the manuscript, conducted the review and drafted the manuscript.

Competing of interests

None.