Introduction

Toxoplasma gondii, an intracellular parasite, infects nearly one-third of the global population. Its prevalence varies by geographic location, ranging from 10% to 80%, and is mainly related to diet and hygiene practices (Robert-Gangneux and Darde, Reference Robert-Gangneux and Darde2012). People often become infected by consuming food or water that is contaminated with oocysts, or by eating undercooked meat that contains tissue cysts. Toxoplasmosis is a rare but potentially fatal disease caused by Toxoplasma infection. It can be divided into 2 types: acquired and congenital. Toxoplasmosis is overwhelmingly acquired; however, the relative burden of congenital versus acquired toxoplasmosis varies across different geographic regions (Milne et al., Reference Milne, Webster and Walker2023). Acquired toxoplasmosis can be further classified based on the immune status of the host (immunocompetent vs immunocompromised) and the specific organs affected, such as the central nervous system, eyes and lungs. Therefore, it impacts several medical fields consisting of obstetrics, ophthalmology, transplantation and oncology, especially during the AIDS epidemic. It can result in significant morbidity and mortality, such as fetal death, neurological deficits, vision loss and other life-threatening conditions (Montoya and Liesenfeld, Reference Montoya and Liesenfeld2004).

It is important to note that toxoplasmosis is treatable, and timely intervention can significantly lessen its impact (Martino et al., Reference Martino, Bretagne, Einsele, Maertens, Ullmann, Parody, Schumacher, Pautas, Theunissen, Schindel, Munoz, Margall and Cordonnier2005; Gajurel et al., Reference Gajurel, Dhakal and Montoya2015; Aerts et al., Reference Aerts, Mehra, Groll, Martino, Lagrou, Robin, Perruccio, Blijlevens, Nucci, Slavin and Bretagne2024). However, diagnosing toxoplasmosis is often difficult for several reasons: (1) there are no specific clinical symptoms; (2) the disease has a low incidence; and (3) identifying risk factors is challenging. Currently available tests can indicate prior exposure to the parasite but are unable to predict the risk of developing disease. An accurate diagnosis for toxoplasmosis requires a comprehensive approach that includes clinical assessments, radiological imaging and microbiological evaluations. Because the clinical symptoms are nonspecific, a definitive diagnosis relies on the biological identification. However, detecting the Toxoplasma organism or DNA is very difficult. First, this parasite primarily resides in the brain, making it rare to obtain histological evidence before death. Second, Toxoplasma DNA in blood or cerebrospinal fluid is usually detectable only in symptomatic individuals, despite the high sensitivity of quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) assays. These difficulties hinder early diagnosis, making it difficult for physicians to administer appropriate treatment. Unfortunately, toxoplasmosis can progress rapidly, particularly in transplant patients, with symptoms that may appear within 2 weeks to 3 months and are associated with a high mortality rate (Gajurel et al., Reference Gajurel, Dhakal and Montoya2015).

It is clinically important to identify the factors that contribute to toxoplasmosis. We focus here specifically on the incidence of clinical toxoplasmosis in individuals who are seropositive for Toxoplasma, rather than Toxoplasma infection, a topic that has been thoroughly reviewed elsewhere (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Kruszon-Moran, Wilson, McQuillan, Navin and McAuley2001; Dubey, Reference Dubey2008; Robert-Gangneux and Darde, Reference Robert-Gangneux and Darde2012). Epidemiological studies and host–parasite interactions indicate that the incidence depends on a combination of host and parasite factors (Figure 1) (Xiao, Reference Xiao, Martin, Preedy, Patel and Rajendram2024). These risk factors can vary significantly due to the various forms of toxoplasmosis. For example, the risk factors for congenital toxoplasmosis differ from those for acquired toxoplasmosis, although some similarities do exist. Variations in clinical presentation, course and progression can arise due to different risk factors (Eraghi et al., Reference Eraghi, Garweg and Pleyer2024; de-la-Torre et al., Reference de-la-Torre, Mejia-Salgado, Eraghi and Pleyer2025b). We review the various factors that influence the incidence and severity of toxoplasmosis. We also discuss methods for characterizing the risk factors related to the parasite and strategies for disease prevention. The ability to predict which infections are likely to remain asymptomatic and which may progress to disease is important for physicians, as it enables them to identify at-risk patients and select the most suitable treatment, ultimately improving patient outcomes.

Figure 1. Risk factors for toxoplasmosis in humans. Toxoplasmosis is a combination of both host and parasite factors. Generally, the more risk factors a person has, the higher their risk of developing toxoplasmosis.

Host risk factors

Immunosuppression

Cell-mediated immune responses are essential for the host to control Toxoplasma infection. When the immune system is compromised, it cannot effectively control both the acute and chronic phases of Toxoplasma infection. This results in the rapid and unchecked multiplication of tachyzoites, which can invade any nucleated cell and lead to a fatal outcome if left untreated. Therefore, immunosuppression is the primary risk factor for severe toxoplasmosis, which may occur in individuals with advanced human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) disease or those who are taking immunosuppressive medications for cancer treatment or following an organ transplant. Additionally, patients treated for autoimmune diseases with corticosteroids or antimetabolites are also at risk (Durieux et al., Reference Durieux, Lopez, Banjari, Passebosc-Faure, Brenier-Pinchart, Paris, Gargala, Berthier, Bonhomme, Chemla, Villena, Flori, Frealle, L’Ollivier, Lussac-Sorton, Montoya, Cateau, Pomares, Simon, Quinio, Robert-Gangneux, Yera, Labriffe, Fauchais and Darde2022).

Toxoplasmic encephalitis (TE) is the most common manifestation in AIDS patients, typically developing when the CD4 cell count falls below 100 mm−3. It almost always represents the reactivation of a prior Toxoplasma infection. Before the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), Luft and Remington (Reference Luft and Remington1992) found that 30% of AIDS patients who were Toxoplasma-seropositive developed TE in the USA, and the incidence is even higher in regions such as Africa, Haiti, Europe and Latin America. Although the introduction of HAART, TE still accounted for 6% of hospital admissions among AIDS-related illnesses in adults living with HIV, as found by a systematic review and meta-analysis (Ford et al., Reference Ford, Shubber, Meintjes, Grinsztejn, Eholie, Mills, Davies, Vitoria, Penazzato, Nsanzimana, Frigati, O’Brien, Ellman, Ajose, Calmy and Doherty2015). The global prevalence of Toxoplasma infection among HIV-positive people is reported to be 35–45%, with the highest seroprevalence found in low-income countries, especially in sub-Saharan Africa (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wang, Liu, Ma, Li, Wei, Zhu and Liu2017; Safarpour et al., Reference Safarpour, Cevik, Zarean, Barac, Hatam-Nahavandi, Rahimi, Bannazadeh Baghi, Koshki, Pagheh, Shahrivar, Ebrahimi and Ahmadpour2020).

Toxoplasmosis in transplant recipients can result from the reactivation of latent infections, the acquisition of organs from seropositive donors with cysts or de novo infection (Gajurel et al., Reference Gajurel, Dhakal and Montoya2015; Aerts et al., Reference Aerts, Mehra, Groll, Martino, Lagrou, Robin, Perruccio, Blijlevens, Nucci, Slavin and Bretagne2024). In solid organ transplant (SOT) recipients, toxoplasmosis primarily occurs when the parasite is transmitted from a Toxoplasma-seropositive donor to a Toxoplasma-seronegative recipient through the transplanted organ. The risk is highest with cyst-forming organs, such as the heart, and lower with organs like the liver, kidney, pancreas or intestine, where the parasite usually does not persist. In hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) recipients, the main risk of toxoplasmosis is the reactivation of a latent infection in seropositive individuals. The risk predisposition for toxoplasmosis is more in HSCT because of the greater duration of immunosuppression as compared to SOT (Khurana and Batra, Reference Khurana and Batra2016). Incidence also varies geographically, based on the prevalence of seropositivity in the general population. A variety of clinical manifestations, such as isolated fever, pneumonitis, meningoencephalitis, chorioretinitis, myocarditis or disseminated toxoplasmosis with multi-organ involvement, usually occur within the first 3 months following transplantation, sometimes as early as 2 weeks post-transplant, leading to high morbidity and mortality rates.

The age of first exposure

Transmission of Toxoplasma from the mother to the fetus through the placenta is highly unlikely if the infection occurs before conception. However, if a primary infection occurs during pregnancy, there is a risk of the parasites being transmitted through the placenta. Since the fetus has an underdeveloped immune system, it cannot effectively control the spread of the parasite, potentially leading to congenital toxoplasmosis (Rico-Torres et al., Reference Rico-Torres, Vargas-Villavicencio and Correa2016). Pregnant women who have acute Toxoplasma infection are often asymptomatic, but the risk of congenital infection ranges from 20% to 50%, varying depending on when the primary infection occurs during pregnancy. For untreated women, the transmission rates are 25%, 54% and 65% during the first, second and third trimesters, respectively (McAuley, Reference McAuley2014; Rico-Torres et al., Reference Rico-Torres, Vargas-Villavicencio and Correa2016). However, newborns with clinical problems were more likely to be born to mothers infected in the first half of gestation than to those infected after week 24 (McAuley, Reference McAuley2014; Conceicao et al., Reference Conceicao, Belucik, Missio, Gustavo Brenner, Henrique Monteiro, Ribeiro, Costa, Valadao, Commodaro, de Oliveira Dias and Belfort2021). The worldwide incidence of congenital infection is estimated at 1.5 cases per 1000 live births, with South America, some Middle Eastern countries and low-income countries being higher (Torgerson and Mastroiacovo, Reference Torgerson and Mastroiacovo2013). In Austria, the USA and France, the incidence of congenital toxoplasmosis is relatively low, with rates of 1.0, 0.5 and 2.9 per 10 000 live births, respectively (Prusa et al., Reference Prusa, Kasper, Pollak, Gleiss, Waldhoer and Hayde2015; Maldonado et al., Reference Maldonado and Read2017; Peyron et al., Reference Peyron, Mc Leod, Ajzenberg, Contopoulos-Ioannidis, Kieffer, Mandelbrot, Sibley, Pelloux, Villena, Wallon and Montoya2017).

Congenital infection with Toxoplasma can lead to pregnancy loss, stillbirth or severe health issues in newborns, such as intellectual disability, blindness and epilepsy. Around 75% of newborns do not show any symptoms at birth. However, a significant number of them may experience neurological and ocular symptoms, along with developmental disabilities, later in life (McAuley, Reference McAuley2014). For example, a follow-up study lasting up to 22 years found that nearly 30% of congenital toxoplasmosis patients developed retinochoroiditis, despite receiving pre- and postnatal treatment (Wallon et al., Reference Wallon, Garweg, Abrahamowicz, Cornu, Vinault, Quantin, Bonithon-Kopp, Picot, Peyron and Binquet2014). The lesions were often identified late: 50% were detected after the age of 3, and some were diagnosed as late as 20. The incidence of retinochoroiditis peaked at ages 7 and 13. Similar findings were reported by Lago et al. (Reference Lago, Endres, Scheeren and Fiori2021), indicating the highest incidence occurred between ages 4–5 and 9–14. These studies highlight the importance of long-term follow-up for patients with congenital toxoplasmosis, particularly in South America, where more virulent strains of the parasite exist (Garweg et al., Reference Garweg, Kieffer, Mandelbrot, Peyron and Wallon2022). The reason, presumably, is that while the acute stage of the infection is resolved, the chronic infection persists within the brain. Tissue cysts can be triggered by factors during development, such as immune dysregulation and hormones (Holland, Reference Holland2009; Lago et al., Reference Lago, Endres, Scheeren and Fiori2021).

Genetic predisposition

As shown by numerous outbreaks, genetic predisposition has a significant influence on the outcomes of Toxoplasma infection (Xiao and Yolken, Reference Xiao and Yolken2015; Dubey, Reference Dubey2021). For instance, during an outbreak of Amazonian toxoplasmosis, some patients unfortunately died from the disease or experienced severe symptoms, while others only displayed mild manifestations (Demar et al., Reference Demar, Ajzenberg, Maubon, Djossou, Panchoe, Punwasi, Valery, Peneau, Daigre, Aznar, Cottrelle, Terzan, Darde and Carme2007; Blaizot et al., Reference Blaizot, Nabet, Laghoe, Faivre, Escotte-Binet, Djossou, Mosnier, Henaff, Blanchet, Mercier, Darde, Villena and Demar2020). In another outbreak in Canada, ocular disease was identified in 20 out of 95 patients diagnosed with acute toxoplasmosis (Burnett et al., Reference Burnett, Shortt, Isaac-Renton, King, Werker and Bowie1998). A French study found that host genetics may have a more significant impact on the severity of illness in immunocompromised patients compared to the genotypes of Toxoplasma (Ajzenberg et al., Reference Ajzenberg, Yera, Marty, Paris, Dalle, Menotti, Aubert, Franck, Bessieres, Quinio, Pelloux, Delhaes, Desbois, Thulliez, Robert-Gangneux, Kauffmann-Lacroix, Pujol, Rabodonirina, Bougnoux, Cuisenier, Duhamel, Duong, Filisetti, Flori, Gay-Andrieu, Pratlong, Nevez, Totet, Carme, Bonnabau, Darde and Villena2009). However, identifying genetic risk factors for toxoplasmosis is challenging due to the various manifestations of the disease and the variability among different populations and studies.

The immune system activation and inflammatory response, which involves chemokines, cytokines and various other mediators, is a common response to Toxoplasma infection. Research has shown that genetic polymorphisms in genes related to the innate immune system are associated with an increased susceptibility to congenital, ocular and cerebral toxoplasmosis. These include genes that encode cytokines such as IL-10, IFN-γ, IL-1β (Naranjo-Galvis et al., Reference Naranjo-Galvis, de-la-Torre, Mantilla-Muriel, Beltran-Angarita, Elcoroaristizabal-Martin, McLeod, Alliey-Rodriguez, Begeman, Lopez de Mesa, Gomez-Marin and Sepulveda-Arias2018), HLA gene DQ3 (Suzuki et al., Reference Suzuki, Wong, Grumet, Fessel, Montoya, Zolopa, Portmore, Schumacher-Perdreau, Schrappe, Koppen, Ruf, Brown and Remington1996; Mack et al., Reference Mack, Johnson, Roberts, Roberts, Estes, David, Grumet and McLeod1999), TLR9 (Peixoto-Rangel et al., Reference Peixoto-Rangel, Miller, Castellucci, Jamieson, Peixe, Elias Lde, Correa-Oliveira, Bahia-Oliveira and Blackwell2009), APEX1 (Aloise et al., Reference Aloise, Coura-Vital, Carneiro, Rodrigues, Toscano, Da silva, Da silva-portela, Fontes-Dantas, Agnez-Lima, Vitor and Andrade-Neto2021), NLR family members NALP1 (Witola et al., Reference Witola, Mui, Hargrave, Liu, Hypolite, Montpetit, Cavailles, Bisanz, Cesbron-Delauw, Fournie and McLeod2011) and NOD2 (Dutra et al., Reference Dutra, Bela, Peixoto-Rangel, Fakiola, Cruz, Gazzinelli, Quites, Bahia-Oliveira, Peixe, Campos, Higino-Rocha, Miller, Blackwell, Antonelli and Gazzinelli2013), ERAP1 (Tan et al., Reference Tan, Mui, Cong, Witola, Montpetit, Muench, Sidney, Alexander, Sette, Grigg, Maewal and McLeod2010), IRAK4 (Bela et al., Reference Bela, Dutra, Mui, Montpetit, Oliveira, Oliveira, Arantes, Antonelli, McLeod and Gazzinelli2012), P2X7 (Jamieson et al., Reference Jamieson, Peixoto-Rangel, Hargrave, Roubaix, Mui, Boulter, Miller, Fuller, Wiley, Castellucci, Boyer, Peixe, Kirisits, Elias Lde, Coyne, Correa-Oliveira, Sautter, Smith, Lees, Swisher, Heydemann, Noble, Patel, Bardo, Burrowes, McLone, Roizen, Withers, Bahia-Oliveira, McLeod and Blackwell2010) and ALOX12 (Witola et al., Reference Witola, Liu, Montpetit, Welti, Hypolite, Roth, Zhou, Mui, Cesbron-Delauw, Fournie, Cavailles, Bisanz, Boyer, Withers, Noble, Swisher, Heydemann, Rabiah, Muench and McLeod2014). Polymorphisms in genes known to be associated with ocular disease, such as ABCA4 and COL2A1, are also linked to ocular disease caused by congenital toxoplasmosis (Jamieson et al., Reference Jamieson, de Roubaix, Cortina-Borja, Tan, Mui, Cordell, Kirisits, Miller, Peacock, Hargrave, Coyne, Boyer, Bessieres, Buffolano, Ferret, Franck, Kieffer, Meier, Nowakowska, Paul, Peyron, Stray-Pedersen, Prusa, Thulliez, Wallon, Petersen, McLeod, Gilbert and Blackwell2008). Toxoplasma has been reported to interact with approximately 3000 human genes or proteins during its lifecycle, which is nearly 10% of the human genome (Carter, Reference Carter2013). Interestingly, many susceptibility genes for toxoplasmosis, such as NALP1, ERAP1, NOD2, ALOX12 and several gene families including HLA, TLR and ABCA, are present in the Toxoplasma–host interactome. This interactome is also enriched with numerous susceptibility genes linked to neuropsychiatric disorders, such as multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease, schizophrenia and bipolar disorder (Carter, Reference Carter2013). Research suggests that chronic Toxoplasma infection may contribute to the development of these diseases (Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Prandovszky, Kannan, Pletnikov, Dickerson, Severance and Yolken2018b).

Toxoplasma antibody titer/level

Toxoplasma IgG levels typically appear 2 weeks after infection, peak at 3 months and remain stable for 6 months before gradually decreasing (Robert-Gangneux and Darde, Reference Robert-Gangneux and Darde2012). Since these antibodies can persist for life, they are not specific for diagnosing toxoplasmosis. However, some studies have found that higher levels of Toxoplasma antibodies may indicate a greater risk of diseases. For example, a Toxoplasma antibody titer greater than 150 IU mL−1 is suggested to be a significant risk factor for developing TE in patients with HIV (Derouin et al., Reference Derouin, Leport, Pueyo, Morlat, Letrillart, Chene, Ecobichon, Luft, Aubertin, Hafner, Vilde and Salamon1996; Hellerbrand et al., Reference Hellerbrand, Goebel and Disko1996; Belanger et al., Reference Belanger, Derouin, Grangeot-Keros and Meyer1999). Subsequent research supports these findings (Vidal et al., Reference Vidal, Diaz, de Oliveira, Dauar, Colombo and Pereira-Chioccola2011; Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Bhondoekhan, Seaberg, Yang, Stosor, Margolick, Yolken and Viscidi2021). In HIV-infected adults, higher levels of Toxoplasma IgG are associated with worse neurocognitive functioning (Bharti et al., Reference Bharti, McCutchan, Deutsch, Smith, Ellis, Cherner, Woods, Heaton, Grant and Letendre2016). Following allogeneic HSCT, patients who developed Toxoplasma reactivation had significantly higher IgG levels than seropositive patients who did not experience reactivation (Meers et al., Reference Meers, Lagrou, Theunissen, Dierickx, Delforge, Devos, Janssens, Meersseman, Verhoef, Van Eldere and Maertens2010). Several studies have found that a high anti-Toxoplasma IgG titer is associated with patients who have primary or active ocular toxoplasmosis (Roh et al., Reference Roh, Yasa, Cho, Nicholson, Uchiyama, Young, Lobo, Papaliodis, Durand and Sobrin2016). In an outbreak of acquired Toxoplasma infection, patients with retinal involvement exhibited high antibody titers (>500 IU mL−1) (Balasundaram et al., Reference Balasundaram, Andavar, Palaniswamy and Venkatapathy2010). Additionally, high levels of Toxoplasma IgG have been found in patients experiencing their first onset of schizophrenia (Leweke et al., Reference Leweke, Gerth, Koethe, Klosterkotter, Ruslanova, Krivogorsky, Torrey and Yolken2004) and in those with cryptogenic epilepsy (Stommel et al., Reference Stommel, Seguin, Thadani, Schwartzman, Gilbert, Ryan, Tosteson and Kasper2001).

Several studies have shown that abnormal levels of Toxoplasma IgG during pregnancy are linked to neurological problems. Brown et al. (Reference Brown, Schaefer, Quesenberry, Liu, Babulas and Susser2005) found that high maternal Toxoplasma IgG antibody titers are associated with a greater risk of schizophrenia in adult offspring. Mortensen et al. (Reference Mortensen, Norgaard-Pedersen, Waltoft, Sorensen, Hougaard, Torrey and Yolken2007) discovered that newborns with elevated Toxoplasma IgG levels also have an increased risk of schizophrenia. Recent studies found that children born to mothers with lower levels of Toxoplasma IgG have an increased risk of autism (Grether et al., Reference Grether, Croen, Anderson, Nelson and Yolken2010; Spann et al., Reference Spann, Sourander, Surcel, Hinkka-Yli-Salomaki and Brown2017). Additionally, pregnant women with higher levels of Toxoplasma IgG antibodies may experience symptoms of anxiety and depression (Groer et al., Reference Groer, Yolken, Xiao, Beckstead, Fuchs, Mohapatra, Seyfang and Postolache2011). However, it is important to note that a limitation of serological investigations examining the association between Toxoplasma infection and psychiatric disorders is the difficulty in establishing causation.

An elevated level of IgG antibodies to Toxoplasma is primarily an indication of high parasite burden. In peripheral blood samples from patients with HIV-1 infection, Vidal et al. (Reference Vidal, Diaz, de Oliveira, Dauar, Colombo and Pereira-Chioccola2011) found a strong correlation between anti-Toxoplasma IgG titers and the PCR detection of Toxoplasma DNA. A study on animals found that Toxoplasma IgG antibody levels were significantly higher in immunocompetent mice experiencing cerebral proliferation of tachyzoites during the chronic stage of infection than those treated with sulfadiazine to inhibit the parasite growth (Singh et al., Reference Singh, Graniello, Ni, Payne, Sa, Hester, Shelton and Suzuki2010). Several studies have shown that mice with high levels of Toxoplasma antibodies tend to have a higher number of tissue cysts (Bezerra et al., Reference Bezerra, Dos Santos, Dos Santos, De andrade and Meireles2019; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Ren, Xin and Jiang2021). Higher IgG levels may also be indicative of an infection caused by a more virulent strain (Bezerra et al., Reference Bezerra, Dos Santos, Dos Santos, De andrade and Meireles2019). There is some evidence to support immunopathology caused by high levels of anti-Toxoplasma IgG. A study showed that the probability of neurocognitive impairment in Toxoplasma-seropositive HIV-infected adults was increased with higher CD4+ T-cell counts, which in turn were associated with higher levels of anti-Toxoplasma IgG (Bharti et al., Reference Bharti, McCutchan, Deutsch, Smith, Ellis, Cherner, Woods, Heaton, Grant and Letendre2016). The authors interpreted this as possible evidence of immune-mediated pathology. Higher levels of anti-Toxoplasma IgG could, in part, be genetic (Duffy et al., Reference Duffy, O’Connell, Pavlovich, Ryan, Lowry, Daue, Raheja, Brenner, Markon, Punzalan, Dagdag, Hill, Pollin, Seyfang, Groer, Mitchell and Postolache2019).

Advanced age

The prevalence of Toxoplasma infection increases with age (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Kruszon-Moran, Wilson, McQuillan, Navin and McAuley2001; de-la-Torre et al., Reference de-la-Torre, Mejia-Salgado, Eraghi and Pleyer2025b), likely due to the gradual accumulation of new infections. With aging, people experience immunosenescence, which is a decline in immune function. This deterioration makes the body less effective at controlling infections, regardless of whether the infections are newly acquired or reactivated from previous infections. The parasite thus can proliferate aggressively within brain or retinal cells, increasing the risk of developing clinical toxoplasmosis, including severe and extensive retinitis (Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Greven, Jaffe, Sudhalkar and Vine1997; Eraghi et al., Reference Eraghi, Garweg and Pleyer2024).

The prevalence of ocular toxoplasmosis among individuals who acquire Toxoplasma infections postnatally is usually low, although there are some geographic variations (de-la-Torre et al., Reference de-la-Torre, Mejia-Salgado, Eraghi and Pleyer2025b). However, the overall prevalence of ocular disease tends to increase with age (de-la-Torre et al., Reference de-la-Torre, Mejia-Salgado, Eraghi and Pleyer2025b). Previous studies have noted that patients with ocular symptoms during the acute stage of Toxoplasma infection are often older (Bosch-Driessen et al., Reference Bosch-Driessen, Berendschot, Ongkosuwito and Rothova2002; Cifuentes-Gonzalez et al., Reference Cifuentes-Gonzalez, Zapata-Bravo, Sierra-Cote, Boada-Robayo, Vargas-Largo, Reyes-Guanes and de-la-Torre2022). Additionally, older patients tend to have more severe disease manifestations, larger retinal lesions and poorer visual outcomes than younger individuals’ factors (Eraghi et al., Reference Eraghi, Garweg and Pleyer2024; de-la-Torre et al., Reference de-la-Torre, Mejia-Salgado, Eraghi and Pleyer2025b). Furthermore, the age at which the first infection occurs plays an important role in the risk of recurrence, with older patients being more susceptible to subsequent episodes.

The connection between Toxoplasma and cognitive impairment in older adults is becoming increasingly concerning (Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Savonenko and Yolken2022). Greater than 20% of adults aged 60 and older experience mental or neurological conditions, with cognitive deficits being the most prominent symptom (Petrova and Khvostikova, Reference Petrova and Khvostikova2021). A recent meta-analysis involving 13 289 healthy individuals found an association between Toxoplasma seropositivity and worse executive functioning, with greater effect sizes observed as age increased (de Haan et al., Reference de Haan, Sutterland, Schotborgh, Schirmbeck and de Haan2021). Several studies report that Toxoplasma seropositivity is associated with cognitive deficits and a higher risk of dementia in older adults (Kusbeci et al., Reference Kusbeci, Miman, Yaman, Aktepe and Yazar2011; de Haan et al., Reference de Haan, Sutterland, Schotborgh, Schirmbeck and de Haan2021).

Parasite risk factors

Parasite burden

Many studies have shown a link between parasite burden and clinical outcomes, indicating that parasitemia is a reliable diagnostic marker for the development of disease. For instance, the concentration of parasites in amniotic fluid is an independent risk factor for fetal outcome. Higher levels are associated with an increased risk of severe consequences, regardless of the gestational age at which the mother seroconverts (Romand et al., Reference Romand, Chosson, Franck, Wallon, Kieffer, Kaiser, Dumon, Peyron, Thulliez and Picot2004; Yamamoto et al., Reference Yamamoto, Targa, Sumita, Shimokawa, Rodrigues, Kanunfre and Okay2017). Case reports involving immunosuppressed patients reveal that those with high parasite loads often exhibit severe symptoms (Meers et al., Reference Meers, Lagrou, Theunissen, Dierickx, Delforge, Devos, Janssens, Meersseman, Verhoef, Van Eldere and Maertens2010; Stajner et al., Reference Stajner, Vasiljevic, Vujic, Markovic, Ristic, Micic, Pasic, Ivovic, Ajzenberg and Djurkovic-Djakovic2013), while patients with low parasite loads typically have favorable outcomes (Patrat-Delon et al., Reference Patrat-Delon, Gangneux, Lavoue, Lelong, Guiguen, le Tulzo and Robert-Gangneux2010; Kieffer et al., Reference Kieffer, Rigourd, Ikounga, Bessieres, Magny and Thulliez2011). Additionally, the presence of Toxoplasma DNA in studied samples has been linked to ocular toxoplasmosis (Costa et al., Reference Costa, Carneiro, Tavares, Andrade, Vasconcelos-Santos, Januario, Menezes-Souza, Fujiwara and Vitor2013), TE in AIDS patients (Alfonso et al., Reference Alfonso, Fraga, Jimenez, Fonseca, Dorta-Contreras, Cox, Capo, Bandera, Pomier and Ginorio2009) and congenital toxoplasmosis (Yamada et al., Reference Yamada, Nishikawa, Yamamoto, Mizue, Yamada, Morizane, Tairaku and Nishihira2011).

While Toxoplasma is usually not found in circulation, patients with toxoplasmosis may have circulating parasites/DNA before the start of clinical symptoms (Martino et al., Reference Martino, Bretagne, Einsele, Maertens, Ullmann, Parody, Schumacher, Pautas, Theunissen, Schindel, Munoz, Margall and Cordonnier2005; Gajurel et al., Reference Gajurel, Dhakal and Montoya2015). The interconversion between latent encysted bradyzoites and rapidly growing tachyzoites is critical for the progression of toxoplasmosis, and clinical symptoms arise from the spread and replication of tachyzoites. PCR amplification, which targets either the rep 529 element or the B1 gene, is used to detect Toxoplasma DNA in blood, tissues or body fluids (Belaz et al., Reference Belaz, Gangneux, Dupretz, Guiguen and Robert-Gangneux2015). Recently, several commercial kits have also been made available (Brenier-Pinchart et al., Reference Brenier-Pinchart, Filisetti, Cassaing, Varlet-Marie, Robert-Gangneux, Delhaes, Guitard, Yera, Bastien, Pelloux and Sterkers2022; Guitard et al., Reference Guitard, Brenier-Pinchart, Varlet-Marie, Dalle, Rouges, Argy, Bonhomme, Capitaine, Guegan, Lavergne, Darde, Pelloux, Robert-Gangneux, Yera and Sterkers2024). In immunocompromised patients, numerous studies have shown that PCR testing enables early diagnosis, significantly improves outcomes and aids in monitoring treatment effectiveness (Martino et al., Reference Martino, Bretagne, Einsele, Maertens, Ullmann, Parody, Schumacher, Pautas, Theunissen, Schindel, Munoz, Margall and Cordonnier2005; Robert-Gangneux et al., Reference Robert-Gangneux, Sterkers, Yera, Accoceberry, Menotti, Cassaing, Brenier-Pinchart, Hennequin, Delhaes, Bonhomme, Villena, Scherer, Dalle, Touafek, Filisetti, Varlet-Marie, Pelloux and Bastien2015; Aerts et al., Reference Aerts, Mehra, Groll, Martino, Lagrou, Robin, Perruccio, Blijlevens, Nucci, Slavin and Bretagne2024). In patients who have undergone allogeneic HSCT, studies have reported that before the 2000s, 90% of patients with toxoplasmosis died from or with the disease (Mele et al., Reference Mele, Paterson, Prentice, Leoni and Kibbler2002; Aerts et al., Reference Aerts, Mehra, Groll, Martino, Lagrou, Robin, Perruccio, Blijlevens, Nucci, Slavin and Bretagne2024), with more than half of the diagnoses being made postmortem. In the last 2 decades, studies using qPCR for earlier diagnoses suggest that up to 60% of patients with toxoplasmosis may be cured with appropriate treatment (Mele et al., Reference Mele, Paterson, Prentice, Leoni and Kibbler2002). However, CNS involvement may lead to debilitating late effects (Gajurel et al., Reference Gajurel, Dhakal and Montoya2015; Aerts et al., Reference Aerts, Mehra, Groll, Martino, Lagrou, Robin, Perruccio, Blijlevens, Nucci, Slavin and Bretagne2024).

The sensitivity of qPCR is influenced by the site from which the sample is collected, the quantity of the sample used for DNA extraction and the specific markers employed. Additionally, PCR shows greater sensitivity in immunocompromised patients compared to immunocompetent patients (Bourdin et al., Reference Bourdin, Busse, Kouamou, Touafek, Bodaghi, Le Hoang, Mazier, Paris and Fekkar2014). Among immunocompromised individuals, PCR is more effective in non-HIV-infected patients compared to those who are HIV-infected (Robert-Gangneux et al., Reference Robert-Gangneux, Sterkers, Yera, Accoceberry, Menotti, Cassaing, Brenier-Pinchart, Hennequin, Delhaes, Bonhomme, Villena, Scherer, Dalle, Touafek, Filisetti, Varlet-Marie, Pelloux and Bastien2015). When diagnosing cerebral toxoplasmosis in patients with AIDS, the sensitivity ranges from 50% to 65%, while the specificity is between 95% and 100% (Bretagne, Reference Bretagne2003). Therefore, a negative PCR result does not exclude the risk of disease in a seropositive individual. Notwithstanding weekly monitoring, one-third of patients already had toxoplasmosis at the first evidence of Toxoplasma replication (Meers et al., Reference Meers, Lagrou, Theunissen, Dierickx, Delforge, Devos, Janssens, Meersseman, Verhoef, Van Eldere and Maertens2010).

An alternative method for measuring parasite burden involves detecting antibodies against Toxoplasma matrix antigens, which are abundantly expressed in tissue cysts (Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Li, Prandovszky, Kannan, Viscidi, Pletnikov and Yolken2016; Dard et al., Reference Dard, Swale, Brenier-Pinchart, Farhat, Bellini, Robert, Cannella, Pelloux, Tardieux and Hakimi2021). The principle behind this approach is that the formation of tissue cysts in the brain triggers the production of antibodies that target cyst proteins such as MAG1. These antibodies can be easily detected in peripheral blood samples. We have demonstrated a strong correlation between MAG1 antibody levels and the number of brain cysts in experimentally infected mice (Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Li, Prandovszky, Kannan, Viscidi, Pletnikov and Yolken2016). In a retrospective case-control study on people with HIV, we found a higher prevalence and level of MAG1 antibodies in those with TE, even 2 years before the onset of the disease (Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Bhondoekhan, Seaberg, Yang, Stosor, Margolick, Yolken and Viscidi2021). In another study, individuals with various forms of toxoplasmosis – such as congenital, ocular, cerebellar and active – show higher frequencies and elevated levels of MAG1 antibodies in their serum compared to those with inactive toxoplasmosis (Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Viscidi, Kannan, Pletnikov, Li, Severance, Yolken and Delhaes2013). In rare cases, serological assays may have limitations, such as the development of toxoplasmosis in seronegative recipients. This can occur for 2 reasons: (1) loss of specific immunoglobulins during pre-HSCT treatments, as a study reported that 30% of children who were seropositive at diagnosis of acute leukemia became seronegative before transplant (Stajner et al., Reference Stajner, Vujic, Srbljanovic, Bauman, Zecevic, Simic and Djurkovic-Djakovic2022), or (2) primary infection in previously uninfected transplant recipients.

Strain type

Toxoplasma was first recognized as a parasite with low genetic diversity that consists of only 3 lineages (I, II and III). Type I is virulent, whereas types II and III are low virulent. However, further studies revealed greater genetic diversity in other continents, particularly in South America. For example, strains from the Amazon region exhibit many unique polymorphisms, often referred to as ‘atypical’ strains. To date, Toxoplasma has been classified into 16 haplogroups based on a global genotyping study of the parasite (Galal et al., Reference Galal, Hamidovic, Darde and Mercier2019). Although it is difficult to draw global conclusions about the virulence of atypical strains, most of them are virulent in mice upon isolation (Darde, Reference Darde2008; Gennari et al., Reference Gennari, Pena, Soares, Minervino, de Assis, Alves, Oliveira, Aizawa, Dias and Su2024). These remarkable differences in virulence arise from the distinct abilities of these strains to modulate host cell signaling pathways (Melo et al., Reference Melo, Jensen and Saeij2011; Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Savonenko and Yolken2022).

Research suggests that the severity of infection in humans may depend on the genotype of the Toxoplasma strain. A systematic review encompassing the full clinical spectrum of toxoplasmosis, including congenital, ocular, immunosuppressed and immunocompetent cases, suggests that virulent strains of Toxoplasma are more frequently associated with severe diseases (Xiao and Yolken, Reference Xiao and Yolken2015). In Brazil, where atypical strains are common, Dubey reported more human outbreaks of clinical toxoplasmosis than any other worldwide geographic region in the last 5 decades (Dubey, Reference Dubey2021). In a systematic review of clinical outcomes in congenital toxoplasmosis, virulent strains of types I and atypical were associated with clinical problems, irrespective of when the infection occurred during pregnancy (Rico-Torres et al., Reference Rico-Torres, Vargas-Villavicencio and Correa2016). Amazonian toxoplasmosis is a severe form of toxoplasmosis caused by highly virulent atypical strains, primarily found in French Guiana. It can result in severe clinical symptoms and even death in immunocompetent individuals (Demar et al., Reference Demar, Hommel, Djossou, Peneau, Boukhari, Louvel, Bourbigot, Nasser, Ajzenberg, Darde and Carme2012; Blaizot et al., Reference Blaizot, Nabet, Blanchet, Martin, Mercier, Darde, Elenga and Demar2019, Reference Blaizot, Nabet, Laghoe, Faivre, Escotte-Binet, Djossou, Mosnier, Henaff, Blanchet, Mercier, Darde, Villena and Demar2020).

The strain type of Toxoplasma can be identified using genetic or serological methods. Genotyping detects variations in DNA sequences, which offers high sensitivity and specificity (Su et al., Reference Su, Shwab, Zhou, Zhu and Dubey2010). The common techniques used include PCR-RFLP, microsatellite analysis and DNA sequencing. However, this approach requires obtaining parasite DNA from an infected host, which is labor intensive and often challenging in immunocompetent asymptomatic patients. Serotyping detects strain-specific antibodies that target the polymorphic sites of immunogenic antigens found within the different strains. Serotypes are defined based on antibody reactions to genotype-specific peptides (Kong et al., Reference Kong, Grigg, Uyetake, Parmley and Boothroyd2003; Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Buka, Cannon, Suzuki, Viscidi, Torrey and Yolken2009; Xiao and Yolken, Reference Xiao and Yolken2015; Sousa et al., Reference Sousa, Fernandes and Correia da Costa2023). This approach is rapid, non-invasive and amenable to most infected people, regardless of their symptoms. A series of GRA peptides, derived from multiple loci such as GRA3, GRA5, GRA6 and GRA7, have been developed to identify the 3 clonal types of humans or animals infected with (Xiao and Yolken, Reference Xiao and Yolken2015; Sousa et al., Reference Sousa, Fernandes and Correia da Costa2023). Non-archetypal strains are more difficult to study due to their genomic diversity, although archetypal peptides have proven useful in identifying these non-archetypal strains (Arranz-Solis et al., Reference Arranz-Solis, Carvalheiro, Zhang, Grigg and Saeij2021; Sousa et al., Reference Sousa, Fernandes and Correia da Costa2023). Well-characterized reference sera and improvements in the sensitivity and specificity of serotyping peptides are urgently needed.

The infectious form of Toxoplasma

Toxoplasma has a complex life cycle that comprises 3 forms: tachyzoites (in groups or clones), bradyzoites (in tissue cysts) and sporozoites (in oocysts) (Dubey et al., Reference Dubey, Lindsay and Speer1998). Tachyzoites and bradyzoites are asexual forms found in intermediate hosts, which represent the acute and chronic phases of infection, respectively. Oocysts are produced only through the sexual reproduction of the parasite in the small intestine of its definitive host, the cat. All 3 forms can potentially infect humans, but their significance varies depending on the local environment, diet and hygiene habits. It has been estimated that around half of all infections result from the ingestion of environmentally resistant oocysts found in water and food (Boyer et al., Reference Boyer, Hill, Mui, Wroblewski, Karrison, Dubey, Sautter, Noble, Withers, Swisher, Heydemann, Hosten, Babiarz, Lee, Meier and McLeod2011). Since 2000, all reported outbreaks in Brazil with known or suspected routes of transmission have been attributed to transmission via oocysts (Pinto-Ferreira et al., Reference Pinto-Ferreira, Caldart, Pasquali, Mitsuka-Bregano, Freire and Navarro2019). Regardless of whether oocysts or cysts are ingested, they transform into tachyzoites that multiply rapidly within host cells. These tachyzoites then spread throughout the body and eventually localize in neural and muscle tissue, where they develop into tissue cysts containing bradyzoites. Transmission of tachyzoites is rare, but it can happen when a mother passes them to her fetus through the placenta (McAuley, Reference McAuley2014).

There is limited evidence on whether the severity of clinical toxoplasmosis in humans is linked to consuming infected meat or oocyst-contaminated food. A study conducted by Boyer et al. (Reference Boyer, Hill, Mui, Wroblewski, Karrison, Dubey, Sautter, Noble, Withers, Swisher, Heydemann, Hosten, Babiarz, Lee, Meier and McLeod2011) suggested that infection with oocysts is a risk factor for congenital toxoplasmosis. The authors distinguished between oocyst infection and bradyzoite infection by measuring IgG antibodies against the Toxoplasma embryogenesis-related protein (Hill et al., Reference Hill, Coss, Dubey, Wroblewski, Sautter, Hosten, Munoz-Zanzi, Mui, Withers, Boyer, Hermes, Coyne, Jagdis, Burnett, McLeod, Morton, Robinson and McLeod2011). They identified that 78% of congenital toxoplasmosis cases reported in the National Collaborative Chicago-based Congenital Toxoplasmosis Study were associated with exposure to oocysts (Boyer et al., Reference Boyer, Hill, Mui, Wroblewski, Karrison, Dubey, Sautter, Noble, Withers, Swisher, Heydemann, Hosten, Babiarz, Lee, Meier and McLeod2011). Dubey (Reference Dubey2021) analysed the differences in clinical manifestations between infections acquired through oocysts and those acquired through meat in human outbreaks of toxoplasmosis from 1966 to 2020. The study found no significant differences in the type or severity of symptoms between the 2 forms of infections. However, a very high number of patients in the oocyst-transmitted outbreaks in Canada, Brazil and India developed ocular lesions. Recent studies have found that oocysts are a significant source of infection in Brazil (Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, VanWormer, Martinez-Lopez, Bahia-Oliveira, DaMatta, Rodrigues and Shapiro2023), a country with a high burden of toxoplasmosis. Additionally, experiments in laboratory animals show that oocyst-induced infections result in more severe disease than tissue cyst or bradyzoite ingestion (Dubey, Reference Dubey2009).

Toxoplasmosis is a combination of host and parasite factors

Toxoplasma is typically regarded as an opportunistic parasite in humans. The outcome of a Toxoplasma infection depends on a complex balance between the host and parasite. Neither the host nor the parasite alone is likely to cause a specific disease. Generally, the more risk factors a person has, the higher their risk of developing toxoplasmosis. For instance, the incidence of TE is notably high in HIV patients whose CD4 cell counts are below 200 cells mL−1 and who have elevated Toxoplasma IgG titers (Derouin et al., Reference Derouin, Leport, Pueyo, Morlat, Letrillart, Chene, Ecobichon, Luft, Aubertin, Hafner, Vilde and Salamon1996; Belanger et al., Reference Belanger, Derouin, Grangeot-Keros and Meyer1999). Patients with ocular disease due to recently acquired infection are usually older and more likely to have Toxoplasma DNA in intraocular fluids (Ongkosuwito et al., Reference Ongkosuwito, Bosch-Driessen, Kijlstra and Rothova1999). Notably, during an outbreak of acquired toxoplasmosis retinitis, affected patients exhibited very high antibody levels and were, on average, older (Burnett et al., Reference Burnett, Shortt, Isaac-Renton, King, Werker and Bowie1998). HIV patients who develop TE have been found to have elevated levels of both Toxoplasma IgG and MAG1 antibodies (Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Bhondoekhan, Seaberg, Yang, Stosor, Margolick, Yolken and Viscidi2021). More newborns with clinical problems are born to mothers who were infected during early pregnancy, particularly with the type I strain (Rico-Torres et al., Reference Rico-Torres, Vargas-Villavicencio and Correa2016). In addition to factors originating from the host and the parasite, other elements also contribute to the severity of toxoplasmosis, such as lack of optimal medical care (Gallant, Reference Gallant2015; Mamfaluti et al., Reference Mamfaluti, Firdausa, Siregar, Hasan and Murdia2023) and co-infection with other pathogens (Bazmjoo et al., Reference Bazmjoo, Bagherzadeh, Raoofi, Taghipour, Mazaherifar, Sotoodeh, Ostadi, Shadmand, Jahromi and Abdoli2023).

The clinical significance of risk factors is determined by both the extent of increased risk and the severity of the disease. Among the identified risk factors, the most important predictors of toxoplasmosis include host immunodeficiency, early-life infection and the parasite burden. Other contributing factors include strain virulence, older age, Toxoplasma IgG, genetic predisposition and oocyst infection. The impact of these factors may vary depending on the specific circumstances. For example, the expression of virulence in a host can be influenced by the host’s immune status (Robert-Gangneux and Darde, Reference Robert-Gangneux and Darde2012). Previous studies have indicated that immune response genes, such as HLA and P2RX7, modify clinical symptoms in children with congenital infections (Mack et al., Reference Mack, Johnson, Roberts, Roberts, Estes, David, Grumet and McLeod1999; Jamieson et al., Reference Jamieson, Peixoto-Rangel, Hargrave, Roubaix, Mui, Boulter, Miller, Fuller, Wiley, Castellucci, Boyer, Peixe, Kirisits, Elias Lde, Coyne, Correa-Oliveira, Sautter, Smith, Lees, Swisher, Heydemann, Noble, Patel, Bardo, Burrowes, McLone, Roizen, Withers, Bahia-Oliveira, McLeod and Blackwell2010). In Europe, low-virulent type II strains of Toxoplasma are highly prevalent, resulting in a minimal impact from strain type (Ajzenberg et al., Reference Ajzenberg, Yera, Marty, Paris, Dalle, Menotti, Aubert, Franck, Bessieres, Quinio, Pelloux, Delhaes, Desbois, Thulliez, Robert-Gangneux, Kauffmann-Lacroix, Pujol, Rabodonirina, Bougnoux, Cuisenier, Duhamel, Duong, Filisetti, Flori, Gay-Andrieu, Pratlong, Nevez, Totet, Carme, Bonnabau, Darde and Villena2009). Elderly patients with ocular toxoplasmosis often experience more severe manifestations, complications and recurrent episodes of inflammation (Eraghi et al., Reference Eraghi, Garweg and Pleyer2024; de-la-Torre et al., Reference de-la-Torre, Mejia-Salgado, Eraghi and Pleyer2025b).

The global burden and prevention of toxoplasmosis

The global burden of toxoplasmosis is increasing for several reasons: (1) as more individuals undergo iatrogenic immunosuppression, the incidence of Toxoplasma-related diseases is likely to rise, especially in countries with high seroprevalence; (2) the global population is aging, and the prevalence of Toxoplasma infection are highest among older individuals; (3) the seroprevalence of Toxoplasma is particularly high in South American, where the high lethality of atypical strains pose a special concern; and (4) while Toxoplasma seroprevalence is decreasing in industrialized countries, this trend may not apply to congenital toxoplasmosis due to ‘peak shift’ dynamics (Robert-Gangneux and Darde, Reference Robert-Gangneux and Darde2012; Milne et al., Reference Milne, Webster and Walker2023).

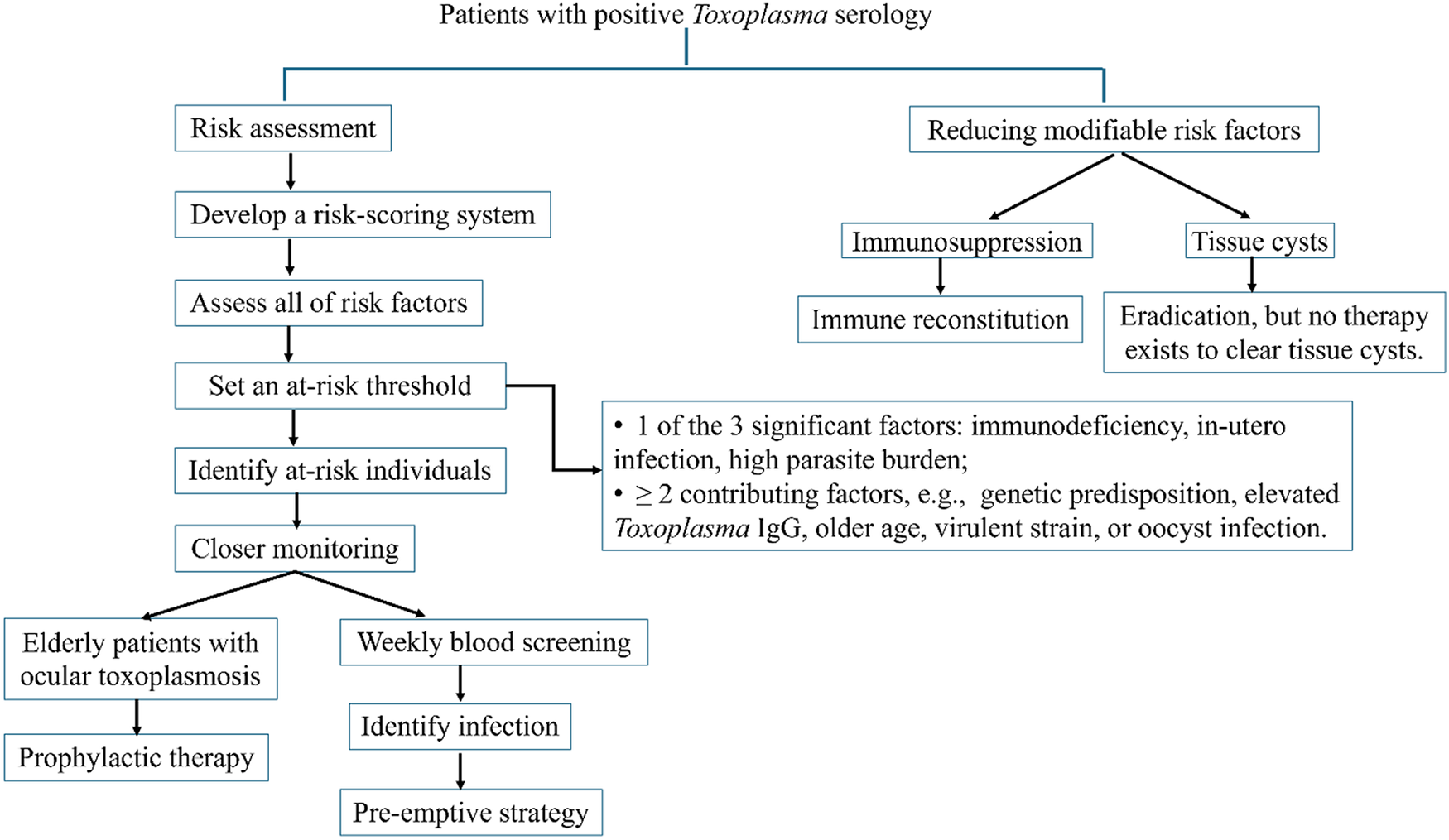

Reducing the burden of toxoplasmosis relies on screening, early detection and timely intervention (Figure 2). For patients with positive Toxoplasma serology, we propose developing a risk-scoring system to identify those at risk. This system should assess all identified risk factors for each individual and establish an at-risk threshold. We suggest setting this threshold when individuals meet either of the following criteria: (1) they have one of the 3 significant factors – immunodeficiency, in utero infection or a high parasite burden, or (2) they exhibit 2 or more contributing factors, such as genetic predisposition, elevated Toxoplasma IgG, older age, virulent strain or oocyst infection. The significant factors have already been shown to be associated with a risk of toxoplasmosis. The potential value of 2 or more contributing factors for the risk of toxoplasmosis can be assessed in a population-based study of the incidence of ocular toxoplasmosis in South America. This region exhibits unique epidemiological characteristics, including a high prevalence and severity of toxoplasmosis, early exposure to the parasite and the presence of more virulent strains (de-la-Torre et al., Reference de-la-Torre, Mejia-Salgado, Eraghi and Pleyer2025b). For those identified as being at high risk, timely intervention, such as closer monitoring or administering appropriate treatment, should be implemented. Experts from the European Conference on Infections in Leukaemia recommend weekly blood screening with qPCR for early detection of toxoplasmosis in haematology patients as a pre-emptive strategy (Aerts et al., Reference Aerts, Mehra, Groll, Martino, Lagrou, Robin, Perruccio, Blijlevens, Nucci, Slavin and Bretagne2024). Research in elderly patients with ocular toxoplasmosis highlighted the importance of prophylactic therapy (Reich and Mackensen, Reference Reich and Mackensen2015; de-la-Torre et al., Reference de-la-Torre, Mejia-Salgado, Eraghi and Pleyer2025b).

Figure 2. Preventive strategies for toxoplasmosis. The prevention of toxoplasmosis relies on screening, early detection and timely intervention, along with addressing risk factors that can be modified or controlled. For patients with positive Toxoplasma serology, the risk of developing toxoplasmosis will be assessed using a risk-scoring system that accounts for all relevant factors. Those who exceed the at-risk threshold will be identified for timely interventions, such as closer monitoring or the administration of appropriate treatment. Improving immune function through reconstitution and eradicating tissue cysts can help prevent reactivation and subsequent diseases.

Another way to lessen the impact of toxoplasmosis is by addressing risk factors that can be modified or controlled (Figure 2). Risk factors for toxoplasmosis can be divided into 2 categories: modifiable and non-modifiable. While age, genetic susceptibility, early-life infection, strain type and infectious form are non-modifiable factors, immunodeficiency and parasite burden are modifiable factors. In a previous study using a humanized mouse model, researchers examined immune reconstitution against Toxoplasma in HIV-infected patients who had received HAART for 1 year (Alfonzo et al., Reference Alfonzo, Blanc, Troadec, Huerre, Eliaszewicz, Gonzalez, Koyanagi and Scott-Algara2002). Mice humanized with PBMC from patients before starting HAART were highly susceptible to infection, while those receiving PBMC from patients on HAART had higher survival rates and lower brain parasite levels. The importance of immune reconstitution in preventing TE in AIDS patients is well established. Toxoplasmosis has now become less of a concern due to the use of HAART (Kodym et al., Reference Kodym, Maly, Beran, Jilich, Rozsypal, Machala and Holub2015).

The tissue cyst within the brain is another modifiable risk factor that, if eradicated, can provide significant clinical benefits. While several drugs, including pyrimethamine, trimethoprim, sulfonamides and folinic acid, can suppress active infection with tachyzoites, none of them are capable of eradicating tissue cysts (Konstantinovic et al., Reference Konstantinovic, Guegan, Stajner, Belaz and Robert-Gangneux2019). Therefore, it is crucial to develop methods that target the cyst stage of this parasite, and recent advances in immunotherapy offer a promising strategy (Konstantinovic et al., Reference Konstantinovic, Guegan, Stajner, Belaz and Robert-Gangneux2019; Suzuki, Reference Suzuki2021). The ability to eradicate cysts may be particularly beneficial for transplant recipients who have infections. By eliminating pre-existing tissue cysts before initiating immunosuppressive therapy, the risk of parasite reactivation and the potential for severe diseases during periods of immune suppression can be minimized. Other vulnerable groups may include the elderly, children with congenital toxoplasmosis and patients with ocular toxoplasmosis. Furthermore, the ability to reduce tissue cysts in farm animals would lower the risk of transmission to humans through undercooked meat.

Future directions

Although much is known about the risk factors for toxoplasmosis, there are still significant areas of research that need further study.

(1) Investigating additional risk factors across the full spectrum of clinical presentations remains an area of active research. For example, the number of cysts/oocysts ingested might have been a contributing factor for toxoplasmosis (Schumacher et al., Reference Schumacher, Elbadawi, DeSalvo, Straily, Ajzenberg, Letzer, Moldenhauer, Handly, Hill, Darde, Pomares, Passebosc-Faure, Bisgard, Gomez, Press, Smiley, Montoya and Kazmierczak2021). Furthermore, the connection between chronic toxoplasmosis and neuropsychiatric disorders, such as cognitive decline, schizophrenia and Alzheimer’s disease, indicates potential new brain-related clinical manifestations (Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Prandovszky, Kannan, Pletnikov, Dickerson, Severance and Yolken2018b).

(2) Our understanding of specific risk factors is still insufficient. For example, while the parasitic cycle is largely understood, more research is needed to further address the clinical significance of acquiring an infection from bradyzoites in meat versus oocysts in the environment. The role of host genetics in the development of toxoplasmosis remains an ongoing area of research.

(3) Although many risk factors for toxoplasmosis have been identified, their predictive power remains unclear. To better understand this, it is useful to quantify the performance of each risk factor using the positive predictive value and negative predictive value, which can be estimated from sensitivity and specificity.

(4) In the past 2 decades, there have been significant advancements in the serological characterization of Toxoplasma infections, including the identification of strain type, parasite burden and oocyst infection. However, the diversity of Toxoplasma population is challenging to the serotyping approach. Few studies have attempted to investigate strain-specific peptides for non-archetypal strains. More assays that offer greater diversity and characterization capabilities are needed.

(5) While PCR screening is sensitive, the criteria for making early diagnosis and initiating pre-emptive therapy still require improvement. For instance, the first positive PCR test may occur simultaneously with the onset of toxoplasmosis, and blood PCR tests can be negative even when the disease is present (Aerts et al., Reference Aerts, Mehra, Groll, Martino, Lagrou, Robin, Perruccio, Blijlevens, Nucci, Slavin and Bretagne2024).

(6) Despite years of research, there has been no effective therapy to eradicate tissue cysts. Several difficulties impede progress, including the need for medications to cross the blood-brain barrier, the existence of a cyst wall and the slow replication and metabolism of tissue cysts. However, recent research into immunotherapy that targets immune checkpoints, such as PD-1, has shown promise for treating tissue cysts (Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Li, Yolken and Viscidi2018a, Reference Xiao, Li, Rowley, Huang, Yolken and Viscidi2023).

Conclusion

It is of clinical significance to identify predictors that determine which patients are at the highest risk of developing toxoplasmosis. This review discusses several risk factors that affect the incidence and severity of toxoplasmosis. The complexity of these risk factors highlights the need to consider both host and parasite aspects during Toxoplasma infection. Research has shown that early detection, prophylactic or preemptive therapy greatly improved the prognosis of patients. Our efforts should also focus on the development of a standardized risk screening system and the control of modifiable risk factors. These approaches would contribute to both epidemiologic studies and the clinical care of individual patients.

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely appreciate the valuable discussions with Profs Viscidi and Yolken.

Author contributions

The authors collaborated to conceive the topic, review literature and contribute to writing and editing each draft.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Stanley Medical Research Institute (SMRI).

Competing interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.

Ethical standards

Not applicable.