Introduction

Parasites are modulators of host populations and important drivers of biodiversity (Poulin and Morand, Reference Poulin and Morand2000; Hatcher et al., Reference Hatcher, Dick and Dunn2012; Selbach et al., Reference Selbach, Mouritsen, Poulin, Sures and Smit2022). Knowledge of epidemiological patterns and processes underpinning pathogen transmission in wildlife, including host traits and parasite characteristics that increase the likelihood of parasite transmission and host switching, will be pivotal to inform future conservation efforts and strategies (Dawson et al., Reference Dawson, Jackson, House, Prentice and Mace2011; Hoberg et al., Reference Hoberg, Agosta, Boeger and Brooks2015; Frainer et al., Reference Frainer, McKie, Amundsen, Knudsen and Lafferty2018).

Helminth parasites exist in dual environments. Consequently, parasite diversity might be affected by both host-related and environmental factors. Host traits that are often associated with an increase in parasite diversity and species richness are, for example, body size, longevity, vagility, geographic range, dietary and habitat breadth as well as social habits (Poulin, Reference Poulin1995, Reference Poulin1997; Arneberg, Reference Arneberg2002; Ezenwa, Reference Ezenwa2003, Reference Ezenwa2004; Ezenwa et al., Reference Ezenwa, Price, Altizer, Vitone and Cook2006; Amundson et al., Reference Amundson, Traub, Smith-Herron and Flint2016; Gutiérrez et al., Reference Gutiérrez, Rakhimberdiev, Piersma and Thieltges2017, Reference Gutiérrez, Piersma and Thieltges2019; Obanda et al., Reference Obanda, Maingi, Muchemi, Ng’ang’a, Angelone and Archie2019). Environmental factors that can influence parasite species richness either directly through the survival of exposed free-living stages in directly transmitted parasites or indirectly by supporting a diversity of invertebrates which often serve as intermediate hosts in indirectly transmitted parasites, are, for example, evaporation rates, temperature, vegetation cover, rainfall and humidity (Landgrebe et al., Reference Landgrebe, Vasquez, Bradley, Fedynich, Lerich and Kinsell2007; Dudley et al., Reference Dudley, Hoberg, Jenkins and Parkinson2015; Spickett et al., Reference Spickett, Junker, Krasnov, Haukisalmi and Matthee2017; Junker et al., Reference Junker, Boomker, Horak and Krasnov2024).

While many studies considered host and environmental factors as determinants of parasite diversity, the majority of these studies pooled data either on various parasite taxa and/or different geographic regions [e.g. crustaceans, monogeneans, platyhelminths and leeches in marine fish studied in the Atlantic, Pacific and Antarctic oceans by Poulin and Rohde (Reference Poulin and Rohde1997) or on various host taxa (e.g. metazoan parasites in 131 vertebrate host species, including fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals, analysed by Poulin et al., Reference Poulin, Mouillot and George-Nascimento2003)].

However, the patterns of host-associated or environment-associated determinants of parasite diversity often differ between host lineages, parasite taxa and/or geographic realms, as is well-illustrated by the study of Kiffner et al. (Reference Kiffner, Stanko, Morand, Khokhlova, Shenbrot, Laudisoit, Leirs, Hawlena and Krasnov2014) on flea communities in various rodent species from Europe, the Middle East and East Africa. Bordes and Morand (Reference Bordes and Morand2009a) concluded that parasite assemblages are shaped by diverse and variable interactions between geographic location, habitat characteristics and host identity. In an analysis including global data sets of terrestrial mammals and using phylogenetically independent contrasts, Morand and Poulin (Reference Morand and Poulin1998) found no relationship between host body size and helminth species richness. In contrast, body mass was one of the main determinants of parasite species richness when looking at fissiped carnivores (Lindenfors et al., Reference Lindenfors, Nunn, Jones, Cunningham, Sechrest and Gittleman2007). Nunn et al. (Reference Nunn, Altizer, Jones and Sechrest2003) investigated parasite species richness in primates on a global scale and demonstrated a positive link between host density and total parasite as well as helminth species richness. Chapman et al. (Reference Chapman, Gillespie and Speirs2005), on the other hand, found no increase in the helminth species richness of specifically colobus monkeys in Africa, despite a significant increase in host density at their study site. The host-associated determinant ‘Host diversity field’ [sensu Villalobos and Arita (Reference Villalobos and Arita2010), i.e. a tendency of an ungulate species to co-occur with many or a few other species] correlated positively with mite species richness in small mammals in the Australasia, Neotropics and Palearctic, but not in the Afrotropics, Indomalaya and Nearctic (Krasnov et al., Reference Krasnov, Grabovsky, Korallo-Vinarskaya, Vinarski, Fernandez and Khokhlova2025). Consequently, when searching for patterns in parasite diversity, it is important to consider data sets with a restricted host and geographic range to avoid loss of resolution by combining data from too many and/or too divergent sources.

Here, we investigated factors influencing the diversity of helminths in wild African ruminants. We studied 3 facets of diversity – species richness, taxonomic diversity and functional diversity. Following the example of Krasnov et al. (Reference Krasnov, Grabovsky, Korallo-Vinarskaya, Vinarski, Fernandez and Khokhlova2025), who considered a host’s parasite fauna as the most suitable measure to assess the influence of host traits on parasite species richness, we based our analyses on the helminth fauna of each host species included in this study, i.e. the assemblage of helminths across the entire geographic range of a given host.

In particular, we tested the effects of different host traits and environmental factors as set out below. Given their large impact on host fitness, high parasite diversity has been associated with strong investment in host immunity (Sheldon and Verhulst, Reference Sheldon and Verhulst1996; Morand and Harvey, Reference Morand and Harvey2000; Giorgi et al., Reference Giorgi, Arlettaz, Christe and Vogel2001; Schmid-Hempel and Ebert, Reference Schmid-Hempel and Ebert2003; Bordes and Morand, Reference Bordes and Morand2009b). However, an energetically costly immune system can channel away resources from the development and maintenance of expensive tissues, such as testes and brain in mammals (Kenagy and Trombulak, Reference Kenagy and Trombulak1986; Jones and MacLarnon, Reference Jones and MacLarnon2004; Tschirren and Richner, Reference Tschirren and Richner2006). We would thus expect parasite diversity to be higher in hosts with a larger relative brain mass (Bordes et al., Reference Bordes, Morand and Krasnov2011).

As mentioned above, larger-bodied hosts are often associated with an increase in parasite species richness as they offer more space and niches for colonization or forage more to maintain body mass, increasing their exposure to infective stages in the environment (Lindenfors et al., Reference Lindenfors, Nunn, Jones, Cunningham, Sechrest and Gittleman2007; Gutiérrez et al., Reference Gutiérrez, Piersma and Thieltges2019). We expected the effect of body size to be more pronounced in indirectly transmitted helminths than in directly transmitted ones.

We predicted a higher species richness in longer-lived hosts as this would increase the opportunity to encounter various parasite species during the host’s lifetime (Gutiérrez et al., Reference Gutiérrez, Piersma and Thieltges2019), particularly in helminths with indirect life cycles.

Social behaviour and host population density can modify infection risk. We expected hosts with larger average group sizes and those living in more densely populated areas to harbour more diverse helminth faunas, especially regarding directly transmitted helminths, because of increased contact rates between infected and susceptible hosts (Ranta, Reference Ranta1992; Arneberg, Reference Arneberg2002; Nunn et al., Reference Nunn, Altizer, Jones and Sechrest2003; Ezenwa, Reference Ezenwa2004; Rifkin et al., Reference Rifkin, Nunn and Garamszegi2012; Cardoso et al., Reference Cardoso, Andreazzi, Maldonado Junior and Gentile2021; Hawley et al., Reference Hawley, Gibson, Townsend, Craft and Stephenson2021).

An increase in especially heteroxenous parasite species richness was predicted in hosts with a wide dietary and habitat breadth and larger geographic range as these would promote survival of a wider range of free-living parasite stages or accommodate a larger variety of intermediate as well as final hosts and their parasite faunas (Torres et al., Reference Torres, Miquel, Casanova, Ribas, Feliu and Morand2006; Lindenfors et al., Reference Lindenfors, Nunn, Jones, Cunningham, Sechrest and Gittleman2007; Gutiérrez et al., Reference Gutiérrez, Piersma and Thieltges2019; Preisser, Reference Preisser2019).

If parasites can successfully exploit similar traits in spatially overlapping host species, they can increase their pool of maintenance hosts (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Bininda Emonds, Stephens, Gittleman and Altizer2014; VanderWaal et al., Reference VanderWaal, Omondi and Obanda2014; Martins et al., Reference Martins, Poulin and Gonçalvessouza2021; Krasnov et al., Reference Krasnov, Van Der Mescht, Matthee and Khokhlova2022). We, therefore, tested for the effect of the number of co-occurring host species and predicted that those with a larger diversity field would support more species-rich parasite faunas.

Environmental and climatic conditions are important mediators of parasite development and transmission (e.g. Altizer et al., Reference Altizer, Dobson, Hosseini, Hudson, Pascual and Rohani2006; Turner and Getz, Reference Turner and Getz2010; Dybing et al., Reference Dybing, Fleming and Adams2013; Preisser, Reference Preisser2019; Martins et al., Reference Martins, Poulin and Gonçalvessouza2021; Junker et al., Reference Junker, Boomker, Horak and Krasnov2022). Helminth species richness has been found directly related to temperature, precipitation and relative humidity (Froeschke et al., Reference Froeschke, Harf, Sommer and Matthee2010), and indirectly through mediation of diversity and abundance of intermediate and final hosts (Calvete et al., Reference Calvete, Estrada, Lucientes, Estrada and Telletxea2003; Ezenwa et al., Reference Ezenwa, Price, Altizer, Vitone and Cook2006; Martins et al., Reference Martins, Poulin and Gonçalvessouza2021).

Different helminth species are governed by different temperature and humidity requirements for their survival (Levine and Todd, Reference Levine and Todd1975; Beveridge et al., Reference Beveridge, Pullman, Martin and Barelds1989; O’Connor et al., Reference O’Connor, Walkden-Brown and Kahn2006; Khadijah et al., Reference Khadijah, Kahn, Walkden-Brown, Bailey and Bowers2013). Especially directly transmitted helminths will thus vary in their tolerance of challenging climatic conditions.

Temperature and precipitation may further influence parasite species richness through their effect on net primary productivity, which is positively correlated with biodiversity and community biomass in wild mammals (Hurlbert and Stegen, Reference Hurlbert and Stegen2014; Belmaker and Jetz, Reference Belmaker and Jetz2015; Gebert et al., Reference Gebert, Njovu, Treydte, Steffan‐Dewenter and Peters2019; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Yan, Kou and Ouyang2023). We predicted high primary productivity to favour helminth species richness in antelopes directly through increased survival rates of stages exposed to the environment and indirectly through its effect on host diversity and abundance. Since we would expect the latter to be true for both intermediate and final hosts, primary productivity should benefit both directly and indirectly transmitted helminths.

Preisser (Reference Preisser2019) demonstrated nematodes, cestodes and trematodes to be affected differently by environmental variables. This is largely explained by their biological differences. Both cestodes and trematodes have indirect life cycles. Nematodes, on the other hand, include taxa with direct and indirect life cycles, with most species infecting African ruminants belonging to the former group. We, therefore, did not only analyse data of all helminths combined, but considered nematodes, cestodes and trematodes separately.

Materials and methods

Data on helminths in African ruminants

A comprehensive data set on the 3 main groups of helminths (nematodes, cestodes and trematodes) parasitizing African ruminants was compiled manually (see Supplementary material, Table S1). The data set was based on a thorough literature search of the vast reprint collections of the National Collection of Animal Helminths at the ARC-Onderstepoort Veterinary Institute and that of Emeritus Professor JDF Boomker, who specialized in the study of helminth diversity in South African wildlife, especially antelopes. These reprint collections focus on parasites in domestic animals and wildlife worldwide and include surveys, taxonomic literature (original species descriptions and revisions) and host-parasite checklists (e.g. Round, Reference Round1968 for nematodes; Pfukenyi and Mukaratirwa, Reference Pfukenyi and Mukaratirwa2018 for trematodes). Publications date back as far as 1893, and many would not have been flagged by means of a strictly electronic database search. Where possible, the original references cited in checklists were consulted for verification. The reference lists of all studied articles were screened for further possible studies for review. In addition, to scan literature as recent as 2024, combinations of the generic names of hosts or keywords such as ‘antelope’, ‘ruminant’, ‘ungulate’, ‘parasite’, ‘helminth’, ‘nematod*’, ‘cestod*’, ‘trematod*’ were used to search Google Scholar. Only species records including the locality and based on the identification of helminth specimens were included, species records based on faecal analysis only were excluded. We also excluded host-parasite records resulting from experimental infections or from hosts in zoological gardens. A total of 225 articles were scanned, of which 213 were retained. Of these, 132 are listed as references in Supplementary material, Table S1, as we did not include references that duplicated host-parasite data already recorded. We updated host scientific names and taxonomic classification according to Wilson and Reeder (Reference Wilson and Reeder2005), and updated helminth classifications, including synonymies, based on the most recent taxonomic literature pertaining to a genus or species.

Host-associated determinants of helminth diversity

For each ruminant host, we selected traits that presumably could be associated with helminth diversity, namely (a) body mass, (b) brain mass relative to body mass, (c) longevity, (d) mean density (the number of individuals per sq. km), (e) mean size of a social group size, (f) diet breadth [the number of prevalent (≥ 20%) dietary categories as defined by Wilman et al. (Reference Wilman, Belmaker, Simpson, de la Rosa and Rivadeneira2014)] consumed, (g) habitat breadth (the number of distinct suitable level 1 IUCN habitats), (h) geographic range size; and (i) diversity field (see above). Data on the first 7 traits were obtained from the COMBINE database (Soria et al., Reference Soria, Pacifici, Di Marco, Stephen and Rondinini2021). Geographic host ranges were taken as Digital Distribution Maps downloaded from the IUCN database (IUCN, 2024), and a 1° × 1° cell grid was overlaid onto these maps. Then, we calculated geographic range size for each host using the ‘lets.range’ function (with the ‘meters’ option) of the package ‘letsR’ (Vilela and Villalobos, Reference Vilela and Villalobos2015) implemented in R Statistical Environment (R Core Team, 2025). Values of geographic range size were ln-transformed prior to further analyses. The diversity field of a species is defined as the mean number of other species that co-occur within its range and calculated diversity field using the function ‘lets.field’ of the ‘letsR’ package.

Environment-associated determinants of helminth diversity

To understand whether helminth diversity was associated with environmental conditions affecting free-living developmental stages and/or the availability of intermediate hosts, 11 environmental variables (mean annual air temperature, temperature seasonality, mean daily air temperatures of the warmest and the coldest quarters, annual precipitation amount, precipitation seasonality, mean monthly precipitation amount of the warmest and the coldest quarters, mean monthly climate moisture index, mean near-surface relative humidity and net primary productivity) were averaged across 1 km × 1 km grids around the centroid of a given host’s geographic range, with a 100-km buffer. Environmental data were obtained from the CHELSA 2.1 datasets (Karger et al., Reference Karger, Conrad, Böhner, Kawohl, Kreft, Soria-Auza, Zimmermann, Linder and Kessler2017, Reference Karger, Conrad, Böhner, Kawohl, Kreft, Soria-Auza, Zimmermann, Linder and Kessler2021). Because of the high correlation between many of the environmental variables, we first extracted 1 (the first) principal component for each of 4 environmental categories [air temperature (T), precipitation (P), climate seasonality (S) and a composite of climate moisture, relative humidity and primary production (MHP)]. These principal components explained from 55.56% (P) to 92.67% (MHP) of the environmental variation of the respective category. Then, we used the scores of these principal components for further analyses.

Helminth traits

Interactions between parasites and their hosts are not only determined by characteristics of the host, but also those of the parasite. We chose the following parasite traits as possible determinants of a parasite’s chances to successfully complete its development and to infect and establish itself in a susceptible ruminant host: (a) life cycle (direct, i.e. parasites that only require 1 host species to complete their life cycle (majority of nematodes) or indirect, i.e. parasites that require at least 2 species to complete their life cycle and are transmitted either by an intermediate host or a vector to the next final host (some nematodes, all cestodes and trematodes)); (b) role of ruminant host [final (all nematodes and trematodes; anoplocephalid cestodes) or intermediate (taeniid cestodes)]; (c) transmission mechanism concerning infection of ruminant host [accidental ingestion of transmission stages in the environment (free-living L3 in the vast majority of Strongylida or L3 contained in the egg, e.g. in Trichuris spp., eggs containing oncosphere larvae in taeniid cestodes, encysted metacercariae in paramphistomoid and fasciolid trematodes); accidental ingestion of intermediate host (heteroxenous nematodes, anoplocephalid cestodes); vector transmitted (filarial nematodes); percutaneous invasion (ancylostomatid and strongyloidid nematodes, schistosomatoid trematodes); autoinfection (cosmocercoid nematodes)]; and (d) predilection site of adults in the final host (rumen; abomasum; abomasum and small intestine; small intestine; small and large intestine; large intestine; lungs and bronchi; liver and bile ducts; blood vascular system; abdominal and peritoneal cavity; tendons, ligaments and musculature; subcutis; eyes).

Calculation of species richness, taxonomic and functional diversity

Estimates of parasite species richness are heavily affected by sampling effort (e.g. number of hosts examined) (Poulin, Reference Poulin2007). Because in many literature sources (checklists, revisions, museum collections) the numbers of examined host individuals were not reported, we first included in our dataset only hosts for which these data were specified and at least 10 individuals were examined. This resulted in data on helminth species richness and composition for 34 antelope species and 1 species of giraffe (see Supplementary material, Table S2). Then, we ran the linear regressions in log-log space separately for the number of all helminths, nematodes, trematodes and cestodes against the number of host individuals examined and substituting the original values with their residual deviations from these regressions.

Comprehensive phylogenies for helminth species recorded from African ruminants are not available. Consequently, we used their taxonomic diversity within a host species as a proxy for their phylogenetic diversity. Taxonomic diversity of all helminths as well as nematodes, trematodes and cestodes separately was calculated as average taxonomic distinctness (Δ +). When these helminth species are placed within a taxonomic hierarchy, the average taxonomic distinctness is the mean number of steps up the hierarchy that must be taken to reach a taxon common to 2 species, computed across all possible species pairs (Clarke and Warwick, Reference Clarke and Warwick1998, Reference Clarke and Warwick1999; Warwick and Clarke, Reference Warwick and Clarke2001). The greater the taxonomic distinctness between helminth species, the higher the number of steps needed and the higher the value of the index Δ + . All helminths or separately nematodes, trematodes and cestodes were fitted into a taxonomic structure with 8 hierarchical levels above species, i.e. genus, subfamily, family, superfamily, order and either phylum (for nematodes, trematodes and cestodes separately) or kingdom (Animalia). We then calculated taxonomic diversity of all helminths, nematodes, trematodes and cestodes for each host using the function ‘taxondive’ implemented in the R package ‘vegan’ (Oksanen et al., Reference Oksanen, Simpson, Blanchet, Kindt, Legendre, Minchin, O’Hara, Solymos, Stevens, Szoecs, Wagner, Barbour, Bedward, Bolker, Borcard, Carvalho, Chirico, De Caceres, Durand, Evangelista, FitzJohn, Friendly, Furneaux, Hannigan, Hill, Lahti, McGlinn, Ouellette, Ribeiro Cunha, Smith, Stier, Ter Braak and Weedon2022).

Functional diversity of all helminths, nematodes, trematodes and cestodes recorded in a given host was calculated as the functional richness (Cardoso et al., Reference Cardoso, Guillerme, Mammola, Matthews, Rigal, Graco-Roza, Stahls and Carvalho2024a). This metric can be calculated based on the unrooted functional tree constructed from the matrix of trait (dis)similarity between species in an assemblage, where functional richness is represented by the sum of the branch lengths (Schmera et al., Reference Schmera, Ricotta and Podani2023; Cardoso et al., Reference Cardoso, Guillerme, Mammola, Matthews, Rigal, Graco-Roza, Stahls and Carvalho2024a). We calculated functional richness of helminth assemblages of a host species using the R package ‘BAT’ (Cardoso et al., Reference Cardoso, Rigal and Carvalho2015, Reference Cardoso, Mammola, Rigal and Carvalho2024b). First, we constructed a matrix of helminth distribution among hosts (D-matrix; host species × helminth species) and a matrix of helminth species traits (T-matrix; helminth species × traits). As recommended by Cardoso et al. (Reference Cardoso, Andreazzi, Maldonado Junior and Gentile2021), we then constructed a neighbour-joining tree for either all helminths or separately for nematodes, trematodes and cestodes regional flea or host T-matrix using the function ‘tree.build’ of the ‘BAT’ package and Gower’s distance. This distance metric allows the construction of a dissimilarity matrix from data composed of continuous, categorical, dichotomous and nominal variables (Gower, Reference Gower1971). The resulting functional trees and D-matrices were then used to calculate functional richness using the function ‘alpha’ of the ‘BAT’ package.

Data analyses

We analysed the association between helminth diversity separately for host-associated and environment-associated factors. Because our data represented values for different host species, we applied phylogenetic generalized linear models (PGLS; Freckleton et al., Reference Freckleton, Harvey and Pagel2002) with species richness (controlled for sampling effort; see above), taxonomic diversity or functional diversity as a response variable and either host traits or environmental factors as explanatory variables. A host phylogenetic tree (topologies and branch lengths) was constructed from a subset of 1000 trees, taken randomly from Upham et al.’s (Reference Upham, Esselstyn and Jetz2019) 10 000 species-level birth-death tip-dated completed trees for 5911 mammal species. From this subset, we built a consensus tree using the ‘consensus.edge’ function of the R package ‘phytools’ (Revell, Reference Revell2012). PGLSs were run using the R package ‘mmodely’ (Schruth, Reference Schruth2023). Prior to analyses, all response and explanatory variables were standardized to have a mean of zero and a standard deviation of unity. This was done using the function ‘decostand’ (with method = ‘standardize’) of the ‘vegan’ package. First, we compiled a list of models with all possible combinations of the explanatory variables, using the ‘get.model.combos’ function. Then, we ran all these models with the ‘pgls.iter’ function and selected the best model based on Akaike Information Criterion, using the ‘select.best.models’ function. Finally, we ran the best model separately for species richness, taxonomic and functional diversity of either all helminths or separately nematodes, trematodes and cestodes. To test whether heteroscedasticity was present in the best PGLS models with significant coefficients, we ran auxiliary regression for each of these models with squared residuals representing response variables. Then, we ran the Breusch–Pagan test for each of these auxiliary regressions using the function ‘bptest’ of the R package ‘lmtest’ (Zeileis and Hothorn, Reference Zeileis and Hothorn2002). The results of the Breusch-Pagan tests indicated no heteroscedasticity (P > 0.15 for all models).

We intentionally did not apply the adjustment of the alpha-level for multiple comparisons (e.g. Bonferroni corrections). Although this can easily be done, this procedure has been strongly criticized by both statisticians and ecologists because it can inflate the rate of Type II errors (Rothman, Reference Rothman1990; Perneger, Reference Perneger1998; Moran, Reference Moran2003; Garcia, Reference Garcia2004; Nakagawa, Reference Nakagawa2004).

Results

Parasite records of the 35 host species included in this study yielded 275 helminth species in 73 genera and 32 families. Nematodes were by far the most diverse group. They were recorded from all hosts and comprised 197 species belonging to 52 genera in 22 families. Trematodes were represented by 49 species in 15 genera and 8 families, while cestodes were the least diverse with 29 species, representing 6 genera and 2 families. Overall, an average (=mean) of 40.9 (11–91) helminth species have been recorded per host species, including an average of 28.5 (7–54) nematode species, followed by an average of 9.0 (1–32) trematode and 5.2 (1–12) cestode species. Conversely, each nematode species has been recorded from an average of 5.1 (1–31) host species, each trematode species from an average of 5.4 (1–20) and each cestode species from 5.9 (1–23) host species.

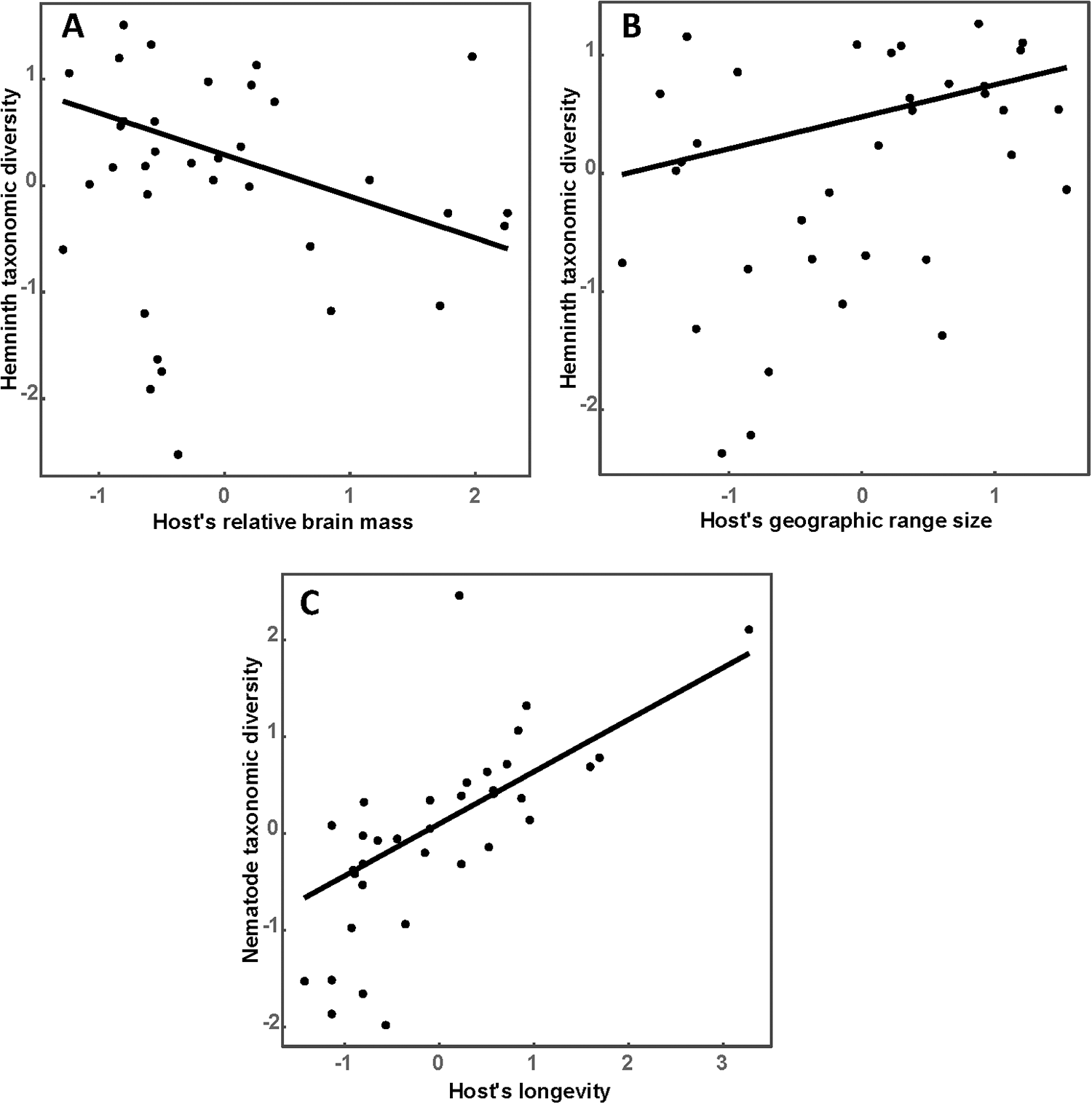

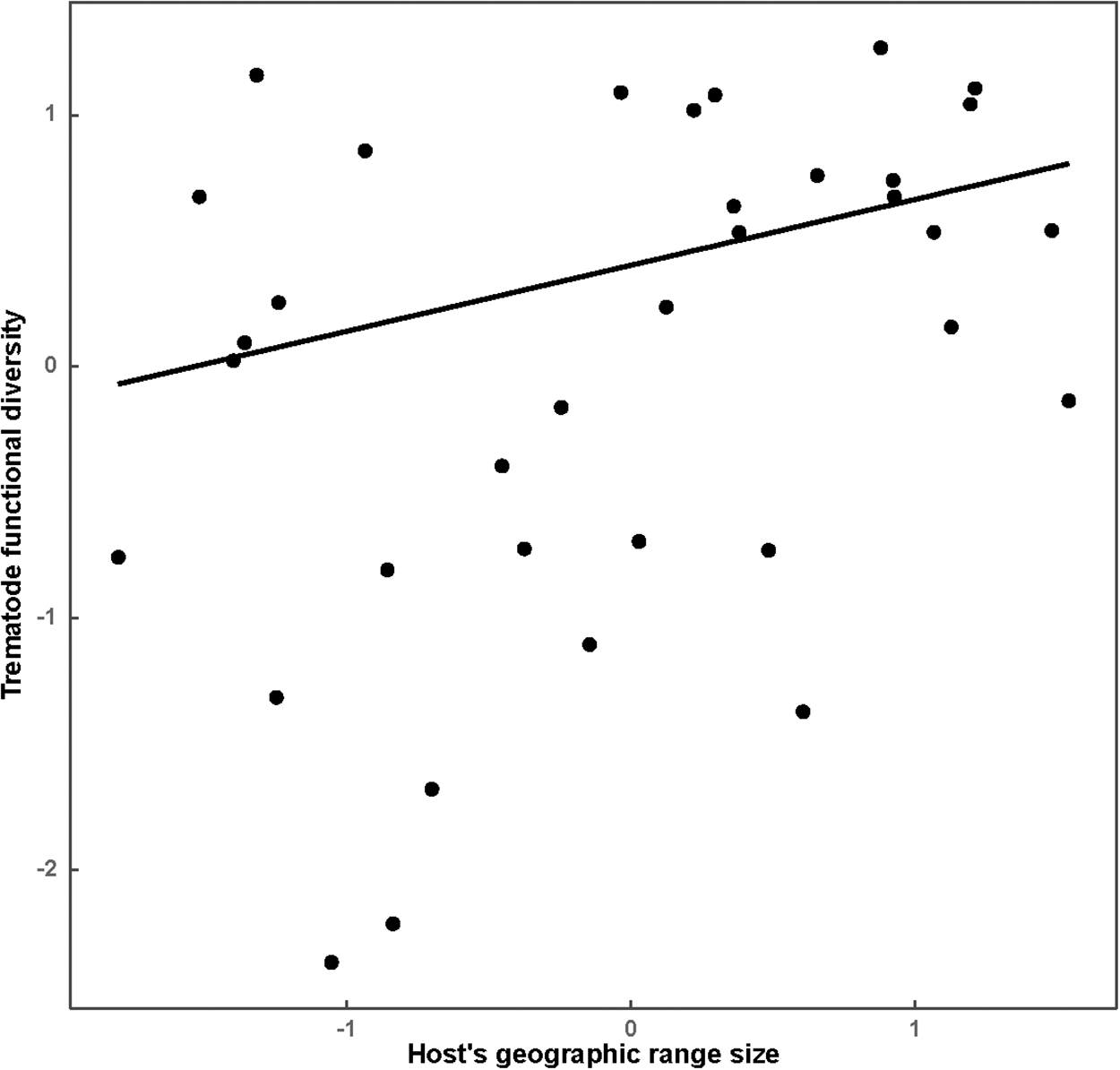

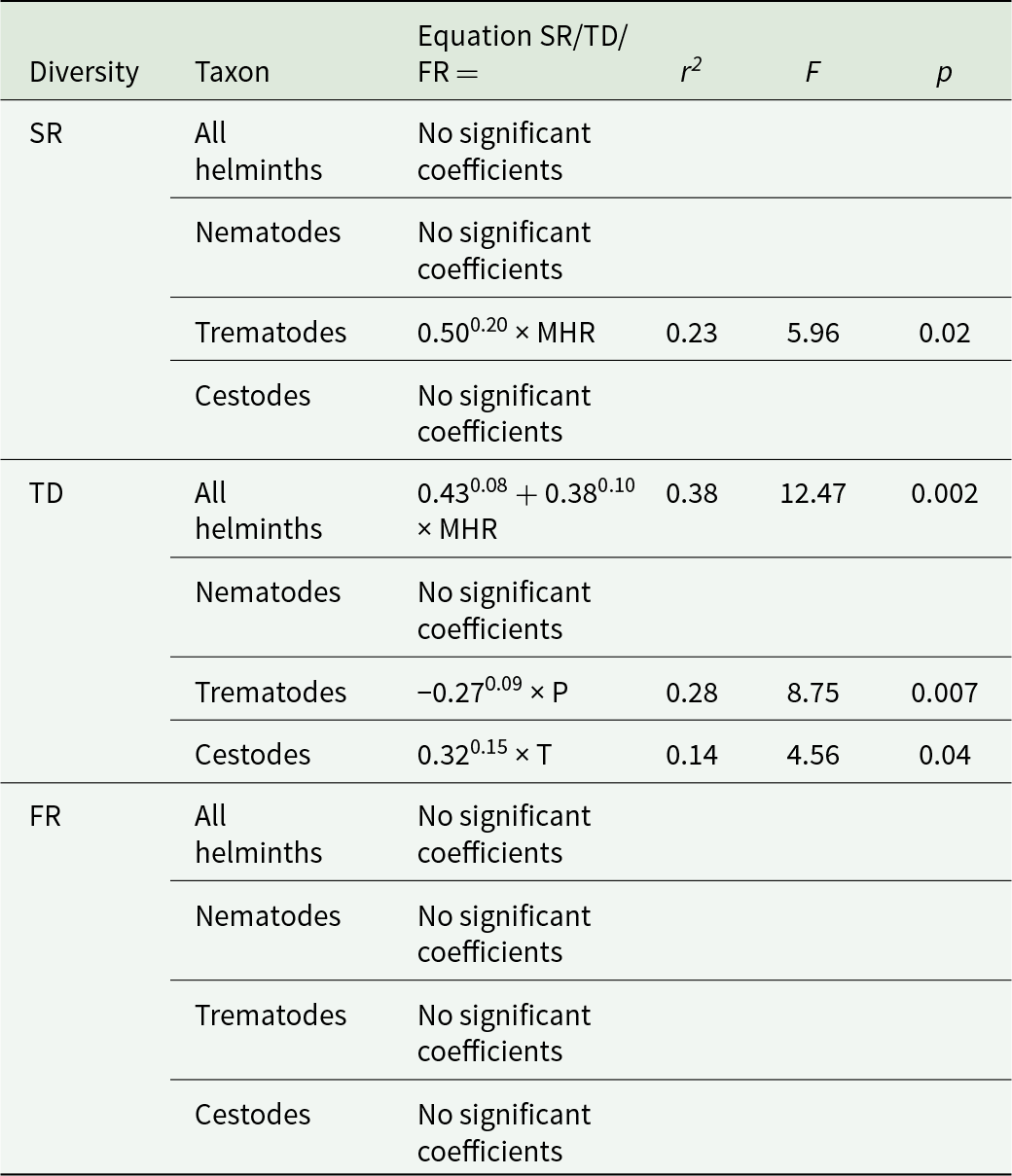

Results of the best phylogenetic linear regressions of the relationships between host traits or environmental factors across a host’s geographic range are presented in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. Species richness of all helminths as well as that of nematodes, trematodes and cestodes increased in ruminants either possessing larger geographic ranges or occupying multiple habitats or both (Table 1; see illustrative examples for species richness of all helminths and of nematodes in Figure 1A and B, respectively). The effect of host traits on the taxonomic diversity of helminths was detected for either all helminth species or nematodes only, whereas we did not find any associations between any host trait and the taxonomic diversity of trematodes or cestodes (Table 1). The taxonomic diversity of all helminths decreased in host species with relatively large brains (Table 1, Figure 2A) but increased in broadly distributed hosts (Table 1, Figure 2B). However, when nematodes only were considered, their taxonomic diversity correlated positively with the longevity of hosts only (Table 1, Figure 2C). Similar to the pattern found for species richness, functional diversity (in terms of functional richness; see above) of all helminths, trematodes and cestodes increased with an increase in the geographic range of a host (Table 1; see illustrative example for trematodes in Figure 3), but not in nematodes. For the latter taxon, no association between functional diversity and either host trait was found.

Figure 1. Relationships between species richness (controlled for sampling effort) of all helminths (A) and nematodes (B) and geographic range size of a host in 35 species of African ruminants.

Figure 2. Relationships between taxonomic diversity of all helminths (A, B) or nematodes (C) and relative brain mass (A), geographic range size (B) and longevity (C) of a host in 35 species of African ruminants.

Figure 3. Relationship between functional richness of trematodes and geographic range size of a host in 35 species of African ruminants.

Table 1. Summary of the best phylogenetically correct linear models (PGLS) of the relationships between ruminant host traits and species richness (corrected for sampling effort; see text for explanation; SR), taxonomic diversity (TD) and functional diversity (functional richness; see text for explanation; FR). Ruminant traits are: RMRM – relative brain mass, LV – longevity, GR – geographic range size and HB – habitat breadth (see text for explanation). Only significant coefficients (P < 0.05) are shown. Superscripts at coefficients – standard errors

Table 2. Summary of the best phylogenetically correct linear models (PGLS) of the relationships between environmental factors across a host’s geographic range and species richness (corrected for sampling effort; see text for explanation; SR), taxonomic diversity (TD) and functional diversity (functional richness; see text for explanation; FR). Environmental factors are principal components of environmental variables representing air temperature (T), precipitation (P) and a composite of climate moisture, relative humidity and primary production (MHP) (see text for explanation). Only significant coefficients (P < 0.05) are shown. Superscripts at coefficients – standard errors

The effect of environmental factors across the geographic range of a host on its helminth diversity (i.e. diversity of the helminth fauna of a host) was weaker than that of host-associated factors. This effect was detected for species richness of trematodes and taxonomic diversity of all helminths, trematodes and cestodes, but not for functional diversity of any set of helminth species (Table 2). In particular, hosts inhabiting environments characterized by higher levels of climate moisture, relative humidity and primary production (MHP) (a) harboured richer trematode faunas (Table 2, Figure 4) and (b) were more taxonomically diverse, although this was the case only when their entire helminth fauna was considered (Table 2, Figure 5A). In addition, the taxonomic diversity of trematodes decreased in hosts from drier areas (Table 2, Figure 5B), whereas the taxonomic diversity of cestodes increased in hosts from warmer areas (Table 2, Figure 5C).

Figure 4. Relationship between species richness of trematodes (controlled for sampling effort) and composite variable describing climate moisture, relative humidity and net primary production across geographic range size of a host in 35 species of African ruminants.

Figure 5. Relationships between taxonomic diversity of (A) all helminths and composite variable describing climate moisture, relative humidity and net primary production; (B) trematodes and precipitation; and (C) cestodes and air temperature across geographic range size of a host in 35 species of African ruminants.

Discussion

Understanding how different mechanisms determine parasite diversity and parasite richness at the macroecological scale could help to predict the effects of future climate and associated environmental changes on parasitism in wild and domestic animals (Brooks and Hoberg, Reference Brooks and Hoberg2007; Stephens et al., Reference Stephens, Altizer, Ezenwa, Gittleman, Moan, Han, Huang and Pappalardo2019). Here, we investigated the importance of host traits and environmental variables as predictors of species richness as well as taxonomic and functional diversity of helminth faunas of African ruminants. In recent decades, progress in molecular taxonomy has shown many species of helminths described in the past to be complexes of cryptic species (Cháves-González et al., Reference Cháves-González, Morales-Calvo, Mora, Solano-Barquero, Verocai and Rojas2022). In light of this, we recognize that the results of our study should be interpreted with caution, as the actual diversity might be higher than reflected in the literature searched. Nevertheless, the trends found appeared rather strong and we believe that a more detailed taxonomic resolution would not alter the general patterns seen. Additionally, papers published by the early parasitologists offer a wealth of data on parasite diversity in especially wildlife hosts that would be impossible to obtain today, be it for ethical reasons or the sheer amount of effort needed to collect the adult helminths during postmortems.

As predicted and shown in previous studies (Nunn et al., Reference Nunn, Altizer, Jones and Sechrest2003; Gutiérrez et al., Reference Gutiérrez, Piersma and Thieltges2019; Dáttilo et al., Reference Dáttilo, Barrozo‐Chávez, Lira‐Noriega, Guevara, Villalobos, Santiago‐Alarcon, Neves, Izzo and Ribeiro2020), parasite species richness increased with a host’s geographic range, habitat breadth or both. This was true for all helminths as well as nematodes, cestodes and trematodes separately. Heteroxenous helminths likely profit from the wider range of invertebrate intermediate hosts encountered in diverse habitats as arthropods, for example, exhibit a wide range of adaptations to different environmental conditions (Joern and Laws, Reference Joern and Laws2013; Sollai et al., Reference Sollai, Giglio, Giulianini, Crnjar and Solari2024). Moreover, both monoxenous and heteroxenous helminths likely benefit from an increase in final host species richness associated with a greater diversity of habitats offered by a wider geographic range (Preisser, Reference Preisser2019). In addition, habitat diversity may also increase the survival rates of the free-living stages of a larger variety of directly transmitted nematodes (Beveridge et al., Reference Beveridge, Pullman, Martin and Barelds1989; Landgrebe et al., Reference Landgrebe, Vasquez, Bradley, Fedynich, Lerich and Kinsell2007).

The above might also explain why we saw an increase in the taxonomic diversity of all helminths in hosts with a wider distribution range. Parasites vary in the environmental conditions they can tolerate or host characteristics they can exploit. However, closely related helminth species, as seen in free-living organisms, often share similar requirements (Ricotta et al., Reference Ricotta, Bacaro, Caccianiga, Cerabolini and Pavoine2018; Krasnov et al., Reference Krasnov, Spickett, Junker, der Mescht L and Matthee2021). A given set of host or environmental characteristics may thus be suitable for a limited set of, likely closely related, helminth species, whereas increased host and habitat diversity as part of a wider distribution range could offer suitable conditions for a larger variety of helminth taxa with divergent requirements.

High parasite diversity has been associated with strong investment in host immunity at the cost of other organ systems (Bordes et al., Reference Bordes, Morand and Ricardo2008; Bordes and Morand, Reference Bordes and Morand2009b; Ducatez et al., Reference Ducatez, Lefebvre, Sayol, Audet and Sol2020). However, results of studies investigating a supposed trade-off between investment in brain development vs immune competency have not been conclusive. Bordes et al. (Reference Bordes, Morand and Ricardo2008) found a positive association between brain size and bat fly species richness, although this only became apparent when taking bat roosting habits into account. In rodents, host brain size was not associated with either flea or helminth richness, but significant negative relationships were seen between brain mass and species richness of gamasid mites (Bordes et al., Reference Bordes, Morand and Krasnov2011). We expected antelope with a larger relative brain mass to support more diverse parasite assemblages but instead the taxonomic diversity of all helminths decreased. In this context, it is interesting to note that, in birds, the relative size of the brain and of organs involved in the immune system tend to be positively correlated (Ducatez et al., Reference Ducatez, Lefebvre, Sayol, Audet and Sol2020). Ducatez et al. (Reference Ducatez, Lefebvre, Sayol, Audet and Sol2020) suggested several scenarios of larger brain size (seen as cognitive ability) influencing parasite species richness in birds. Larger behavioural and foraging flexibility could result in higher exposure rates to parasites, but conversely, host cognitive abilities could assist in the avoidance or response to parasites, which might explain our findings. Clearly, the relationship between host brain size and parasite species richness is not a straightforward one and can be influenced by coevolutionary interactions, including the interplay of multiple host and parasite factors such as the parasite’s transmission mode, the host’s immune competence, its ecological niche and behavioural traits (see Ducatez et al., Reference Ducatez, Lefebvre, Sayol, Audet and Sol2020).

Host traits were only linked to taxonomic diversity when considering all helminths or nematodes separately. We saw no effect of host traits on taxonomic diversity when analysing trematodes or cestodes separately. This could reflect the fact that cestodes were represented by 2 families, Anoplocephalidae (20 species) and Taeniidae (9 species), only, and the trematode fauna of antelopes was dominated by members of the superfamily Paramphistomatoidea (38 of 49 species).

In nematodes, taxonomic diversity increased with host longevity. This is in line with previous studies (Morand and Harvey, Reference Morand and Harvey2000; Nunn et al., Reference Nunn, Altizer, Jones and Sechrest2003) and our expectation that a longer lifespan would afford hosts an extended opportunity to accumulate a varied helminth fauna. We did, however, expect the impact of longevity to be stronger in helminths with an indirect life cycle, where it, in fact, showed no effect. Interestingly, both Ezenwa et al. (Reference Ezenwa, Price, Altizer, Vitone and Cook2006) and Cooper et al. (Reference Cooper, Kamilar and Nunn2012) found a decrease in parasite diversity with host longevity in ungulates, suggesting that greater parasite burden might lead to higher host mortality rates in ungulates or, alternatively, that long-lived host species invested in improved immune defences against parasites.

There was no association between host traits and functional richness in nematodes, but functional richness increased with geographic range in all helminths as well as in trematodes and cestodes separately, suggesting that the latter 2 are the drivers of the effect seen in all helminths. A shared trait between cestodes and trematodes in antelopes is that they are exclusively indirectly transmitted. As is evident from their common names, trematodes have different predilection sites: rumen flukes (Paramphistomoidea), liver flukes (Fasciolidae) and blood flukes (Schistosomatidae). Their freshwater snail hosts differ in their water and temperature requirements for survival and reproduction and consequently in their ability to colonize diverse habitats (De Kock and Wolmarans, Reference De Kock and Wolmarans2005; Pfukenyi and Mukaratirwa, Reference Pfukenyi and Mukaratirwa2018; Vázquez et al., Reference Vázquez, Alda, Lounnas, Sabourin, Alba, Pointier and Hurtrez-Boussès2018). In addition, trematodes vary in their transmission mode. While the intermediate hosts of all 3 trematode groups are infected via percutaneous invasion, the final hosts of rumen and liver flukes are infected through ingestion of metacercariae that are encysted on the vegetation near waterbodies, whereas in blood flukes, infection of the final host is achieved through percutaneous invasion by free-swimming cercariae (Abe et al., Reference Abe, Guan, Guo, Kassegne, Qin, Xu, Chen, Ekpo, Li and Zhou2018), increasing their dependence on permanent water bodies. Differences in the trematodes’ ability to exploit different intermediate hosts and variations in their transmission mode that result in varied habitat requirements might contribute to larger functional trematode diversity in hosts with a wider geographic range. Similar interactions might be in play concerning cestodes. Anoplocephalid cestodes, which dominate the cestode fauna of antelopes, depend on oribatid mites as intermediate hosts. Oribatid mite communities are known to be modified by changes in moisture and temperature (Gergócs and Hufnagel, Reference Gergócs and Hufnagel2009).

Among the environmental factors influencing helminth diversity, MHP was the most significant one. Higher levels of primary production resulted in increased trematode species richness. As mentioned, by far the majority of trematodes infecting African ruminants are members of the Paramphistomatoidea, using freshwater snails as intermediate hosts. Their infection patterns are thus influenced by both the abundance of infected definitive hosts and their grazing patterns as well as the abundance and efficiency of the snail intermediate hosts (Pfukenyi and Mukaratirwa, Reference Pfukenyi and Mukaratirwa2018). Factors that promote the survival and activity of freshwater snails, such as temperature and precipitation patterns would thus have a pronounced impact on paramphistomatoid diversity. Vulnerability of freshwater snail hosts to dry climatic conditions may also be the reason for the decrease in trematode taxonomic diversity seen in hosts occurring in drier areas.

In addition, an increase in MHP was associated with an increase in taxonomic diversity in all helminths. As mentioned, different helminth species have different temperature and humidity requirements for their development and vary in their tolerance of challenging climatic conditions (Levine and Todd, Reference Levine and Todd1975; Beveridge et al., Reference Beveridge, Pullman, Martin and Barelds1989; O’Connor et al., Reference O’Connor, Walkden-Brown and Kahn2006; Khadijah et al., Reference Khadijah, Kahn, Walkden-Brown, Bailey and Bowers2013). Adequate levels of climate moisture and humidity can favour the survival of exposed infective stages of especially direct life cycle species, whereas high evaporation rates and low humidity associated with high temperatures may lead to desiccation (Fedynich et al., Reference Fedynich, Monasmith and Demarais2001; Landgrebe et al., Reference Landgrebe, Vasquez, Bradley, Fedynich, Lerich and Kinsell2007; Dybing et al., Reference Dybing, Fleming and Adams2013). Similarly, soil moisture and temperature were 2 of the most important factors for the successful development of the infective L3 in gastrointestinal nematodes of ruminants (Callinan et al., Reference Callinan, Morley, Arundel and White1982; Khadijah et al., Reference Khadijah, Kahn, Walkden-Brown, Bailey and Bowers2013; Sturrock et al., Reference Sturrock, Yiannakoulias and Sanchez2017). Moreover, temperature and precipitation may influence the diversity and abundance of intermediate hosts (Calvete et al., Reference Calvete, Estrada, Lucientes, Estrada and Telletxea2003), thus affecting the species richness of assemblages of indirectly transmitted helminths. Primary productivity, the third component of MHP, predicted the biodiversity and community biomass of wild mammals on Mt. Kilimanjaro (Gebert et al., Reference Gebert, Njovu, Treydte, Steffan‐Dewenter and Peters2019). Similarly, higher primary productivity at lake sites on the Tibetan plateau, as evidenced by higher vegetation coverage and plant diversity, led to higher population densities of Tibetan antelopes (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Yan, Kou and Ouyang2023). As set out above, both host diversity and host population size are positively linked to parasite species richness. Froeschke and Matthee (Reference Froeschke and Matthee2014) showed a positive association between higher percentage vegetation cover and the prevalence and abundance of strongyloid nematodes in Rhabdomys pumilio. It is thus not surprising that taxonomic diversity of both directly and indirectly transmitted helminths increased with higher MHP levels.

Contrary to our findings that taxonomic diversity in cestodes increased in hosts from warmer areas, cestode richness in cricetid rodents was higher in areas with lower mean annual temperatures (Preisser, Reference Preisser2019). This emphasizes that, even within helminth groups, different taxa have adapted differently to environmental conditions. This might reflect variation in the response of their respective intermediate hosts to environmental changes as, for example, seen in oribatid mites (Gergócs and Hufnagel, Reference Gergócs and Hufnagel2009).

In summary, our results revealed a mosaic of varied responses to different sets of host and/or environment related variables between the various groups of helminths. The fact that some effects were only apparent in the overall helminth fauna while others seemed associated with either nematodes, cestodes or trematodes emphasizes the importance of analyses that focus on a select range of hosts and do not span the net of parasite taxa considered too widely.

Supplementary material

The supplementary materials for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182025101510

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article. The datasets used and/or analyses are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Author contribution

KJ and BRK conceived the study. BRK compiled the host data set, and KJ compiled the parasite data set. BRK performed statistical analyses. KJ and BRK wrote the article.

Financial support

KJ received funding from the Department of Agriculture, South Africa (project number A150).

Competing interests

The authors declare there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

All applicable institutional, national and international guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed.