Introduction

The family Camallanidae Railliet and Henry, 1915 (Nematoda: Rhabditida) (De Ley and Blaxter, Reference De Ley, Blaxter and Lee2002) includes parasitic nematodes that inhabit the gastrointestinal tracts of amphibians, fish and reptiles (Moravec, Reference Moravec1998). The representatives of this family are distinguished from other nematodes by 2 main characteristics: the reddish coloration of the body in life and the brown-orange, well-sclerotized buccal capsule (Rigby and Rigby, Reference Rigby, Rigby and Schmidt-Rhaesa2014).

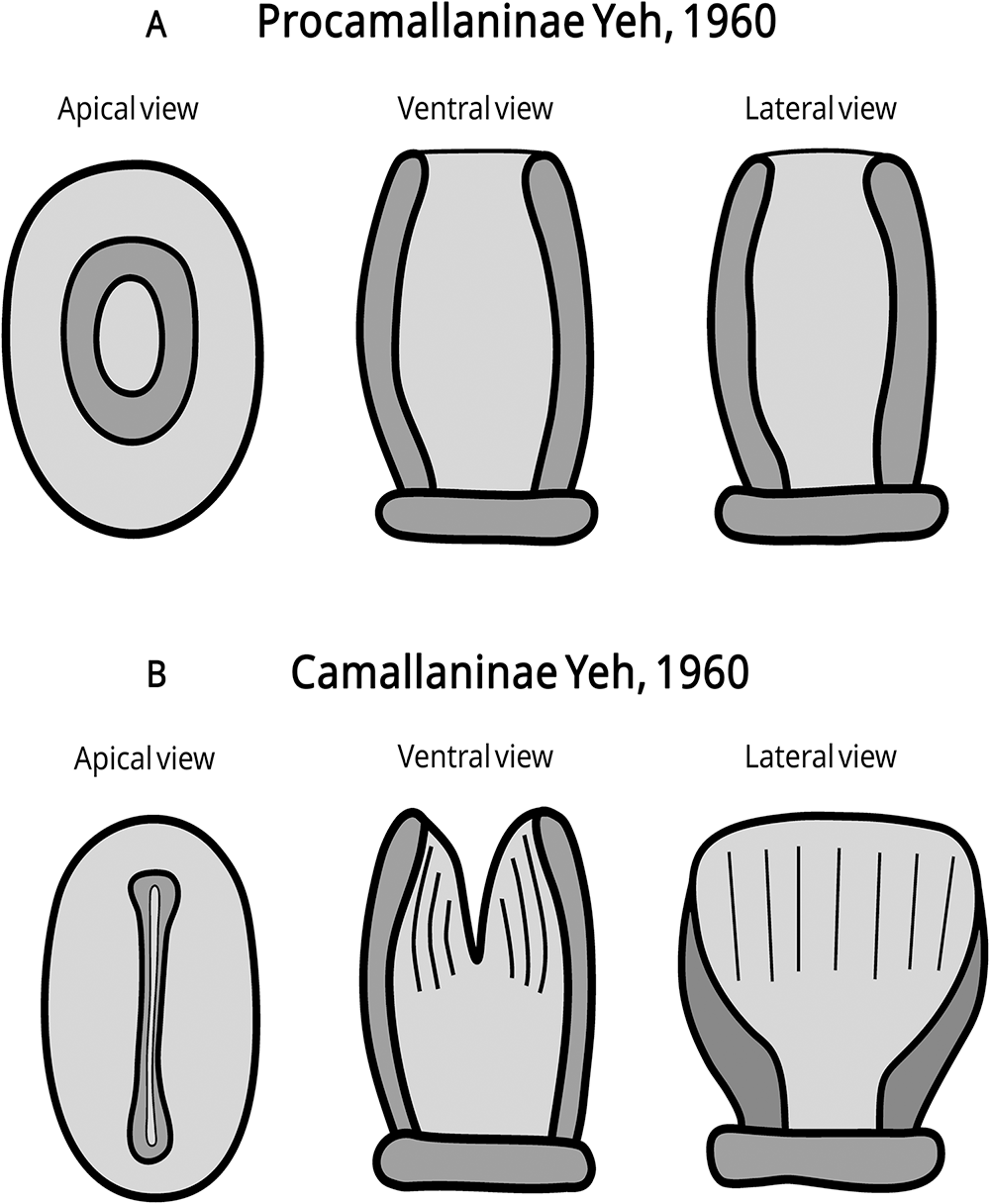

The classification of genera within the family Camallanidae is based on the morphology of the buccal capsule, specifically on the presence, shape and distribution of internal ridges within the capsule, and on the trident morphology (Rigby and Rigby, Reference Rigby, Rigby and Schmidt-Rhaesa2014). Yeh (Reference Yeh1960) divided the family into 2 subfamilies based on the buccal capsule structure: Procamallaninae Yeh, 1960, which features a continuous and rounded, cup-like buccal capsule, and Camallaninae Yeh, 1960, with a buccal capsule divided into 2 shell-like lateral valves.

The taxonomic history of the family Camallanidae is complex, with numerous genera proposed over the years. However, many of which have been synonymized or had their status questioned. These inconsistencies in the systematics of these genera arise from a diversity of variations in the buccal capsule morphology, particularly the internal ornamentations. These findings have led to some debate about the actual number of genera within Camallanidae (Svitin et al., Reference Svitin, Truter, Kudlai, Smit and Du Preez2019).

Despite the existence of checklists for nematode species parasitizing fish in Brazil (Luque et al., Reference Luque, Aguiar, Vieira, Gibson and Santos2011) and specifically in the Brazilian Amazon biome (Santos Reis et al., Reference Santos Reis, Santos, Nunes and Mugnai2021), and turtles in South America (Mascarenhas and Müller, Reference Mascarenhas and Müller2021) and Neotropical region (Izidro de Brito and Figueiredo Lacerda, Reference Izidro de Brito and Figueiredo Lacerda2025), a focused and comprehensive survey of Camallanidae species specifically recorded in Brazil remains to be done.

The vast diversity of biomes and vertebrates in the country contributes to a high number of parasitic helminth species, including camallanids. There are several records of Camallanidae in Brazil (Mascarenhas and Müller, Reference Mascarenhas and Müller2021; Santos Reis et al., Reference Santos Reis, Santos, Nunes and Mugnai2021); however, the diversity of this group is still relatively unknown, as we do not have a compilation of its geographical distribution in the country or its distribution among host species.

The accurate species identification is fundamental for understanding parasite ecology, host specificity, geographic distribution and potential impacts on host health (Kholia and Fraser-Jinkins, Reference Kholia and Fraser-Jinkins2011; Vink et al., Reference Vink, Paquin and Cruickshank2012; Smales, Reference Smales2022). Moreover, a checklist provides data for further investigations, highlighting unexplored regions or host groups and taxa that need to be investigated. At the same time, a taxonomic key is indispensable for both beginners and experienced parasitologists to identify parasites confidently. Without these tools, misidentifications can propagate, leading to flawed scientific conclusions and impeding the advancement of parasitological knowledge.

Thus, the objective of this study is to present a comprehensive checklist of Camallanidae species reported in Brazil and to provide a new, updated taxonomic key for the camallanid genera, based on a critical, revised understanding of their morphology and phylogenetic data.

Material and methods

Bibliographical research on the Camallanidae species, their host records and geographical reports in Brazil was conducted by considering articles identified in the indexing databases Google Scholar, “Periódicos Capes-Brazil”, PubMed, SciELO and Scopus. The key terms used included ‘Camallanidae’ and related taxonomic names (at the genus level), combined with ‘Brazil’ and host-related keywords (‘fish’, ‘turtle’, ‘reptiles’, ‘Testudines’, 'amphibians'). Different combinations of these terms were tested (e.g. ‘Camallanidae Brazil’, ‘Camallanidae fish Brazil’, ‘Camallanidae turtle Brazil’) to retrieve all available records of Camallanidae nematodes parasitizing vertebrate hosts in the country.

Monographic works and abstracts presented at scientific events were not considered. Furthermore, we reviewed all records presented in checklists or similar works that present nematode surveys in Brazil: Vicente et al. (Reference Vicente, Rodrigues and Gomes1985), Vicente et al. (Reference Vicente, Rodrigues, Gomes and Pinto1993), Moravec (Reference Moravec1998), Vicente and Pinto (Reference Vicente and Pinto1999), Thatcher (Reference Thatcher2006), Luque et al. (Reference Luque, Aguiar, Vieira, Gibson and Santos2011), Eiras et al. (Reference Eiras, Velloso and Pereira2016), Lehun et al. (Reference Lehun, Hasuike, Silva, Ciccheto, Michelan, Rodrigues, Nicola, Lima, Correia and Takemoto2020), Mascarenhas and Müller (Reference Mascarenhas and Müller2021), Santos Reis et al. (Reference Santos Reis, Santos, Nunes and Mugnai2021), and Izidro de Brito and Figueiredo Lacerda (Reference Izidro de Brito and Figueiredo Lacerda2025).

This review was based on a thorough reanalysis of all references cited by the authors, including checks of the species, hosts and localities reported in the original publications. When the original works were not accessible or the information conflicted with that presented in the checklists, such records were considered invalid. Thus, only confirmed records were considered in the results.

We also produce a map illustrating the geographical distribution of Spirocamallanus inopinatus (Travassos, Artigas and Pereira, 1928) in Brazil. The map was generated using a spreadsheet and QGIS 3.28 software (Quantum, 2024). The geographic coordinates, hosts and references used are presented in Supplementary Material 1.

To confirm the taxonomic status for some species, we examined by light microscopy the following camallanids specimens deposited in the Helminthological Collection of Oswaldo Cruz Institute (CHIOC)-Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Oncophora melanocephala (Rudolphi, 1819) CHIOC 32248a-b, 32249 a-b, 33967; Paracamallanus amazonensis Ferraz and Thatcher, 1992 CHIOC 32945, 32948, 32956 e 32957; Procamallanus petterae Kohn and Fernandes, 1988 CHIOC 32430b; Procamallanus (Procamallanus) peraccuratus Pinto, Fabio, Noronha and Rolas, 1976 CHIOC 31084b-c; Procamallanus (Spirocamallanus) intermedius Pinto, Fabio, Noronha and Rolas, 1974 CHIOC 14658, 31022b-h, 31023a-c; Procamallanus (Spirocamallanus) pimelodus Pinto, Fabio, Noronha and Rolas, 1974 CHIOC 30993b-i, 30999b-f; and Procamallanus (Spirocamallanus) saofranciscencis (Moreira, Oliveira and Costa, Reference Moreira, Oliveira and Costa1994) CHIOC 37857, 37858.

The checklist is organized alphabetically by camallanid genera and species. The host species names were updated according to Froese and Pauly (Reference Froese and Pauly2025) for fish and Uetz et al. (Reference Uetz, Freed, Aguilar, Reyes, Kudera and Hošek2025) for reptiles. We also provide records of camallanids in Brazil, analysing the status of the listed species and some taxonomic changes where applicable. Our records for each nematode taxon include any existing synonyms, host records, host habitat, sites of infection, locality records indicating Brazilian states, Brazilian biomes, deposit codes in helminthological collections (if available), references, unconfirmed reports from previous surveys and remarks. Remarks were presented when we analysed specimens, proposed relocating a species or discussed the species’ status.

The abbreviations for the helminthological collections reported in this study are: Collection of Non-Arthropod Invertebrates of the Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi (MPEG), Helminthological Collection of Oswaldo Cruz Institute (CHIOC), Helminthological Collection of the Institute of Biosciences of Botucatu (CHIBB), Helminth Collection of the Laboratory of Parasitology of Wild Animals of the Federal University of Pelotas (CHLAPASIL-UFPel), Helminth Collection, University of Nebraska State Museum, Harold W. Manter Laboratory (HWML) and National Institute for Amazonian Research (INPA).

Results

Based on the literature review and morphological analysis, we recognize only 2 subfamilies and 13 genera valid within Camallanidae. We followed 2 key conclusions proposed by Ailán-Choke and Pereira (Reference Ailán-Choke and Pereira2021) concerning the current classification of this family based on the buccal capsule morphology: (i) this classification remains consistent for some genera, reflecting morphological features congruent with the phylogeny of these nematodes; and (ii) it does not provide support for recognition of subgenera. Therefore, it is important to note that the subgeneric classification within Camallanidae should not be considered.

Based on a comprehensive literature review and our extensive analyses of camallanid specimens, the subfamilies were distinguished based on morphology of the buccal capsule (round without divisions vs. divided into 2 valves) (Fig. 1). For the genera, we used the presence and morphology of tridents (accessory structures on the buccal capsule), as well as the presence, morphology and distribution pattern of internal ornamentations in the buccal capsule (including spiral ridges, longitudinal ridges, punctations, ridges separated by a gap, tooth-like structures and a smooth internal surface). The new taxonomic identification key for camallanids is provided at the end of the article, including a diagnosis for Camallanidae, and diagnostic criteria for its subfamilies and genera.

Figure 1. Illustrative drawing of buccal capsule morphology of the subfamilies within the family Camallanidae Railliet and Henry, 1915. (A) Procamallaninae; (B) Camallaninae.

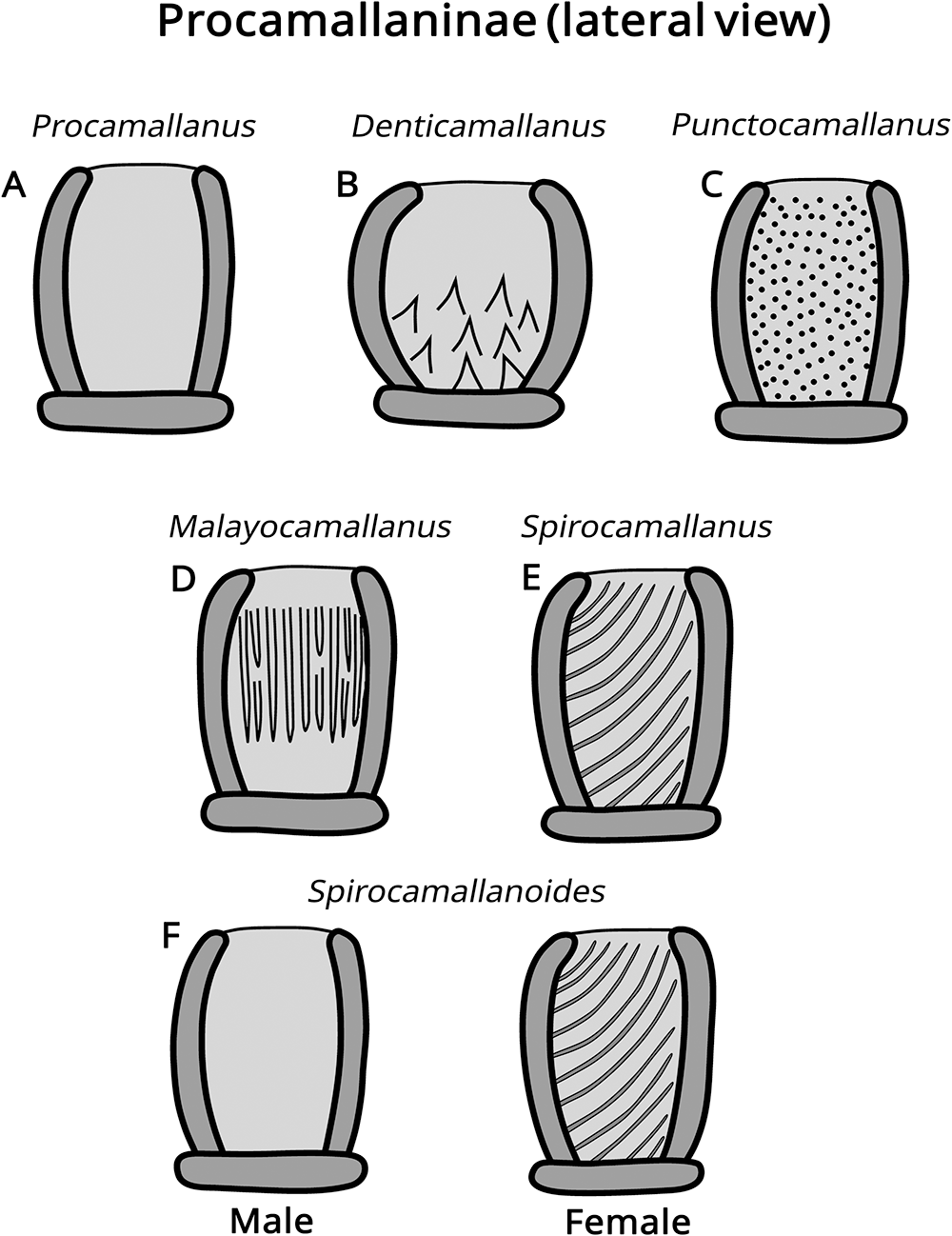

The subfamily Procamallaninae (buccal capsule rounded without divisions) includes the genera Denticamallanus Moravec and Thatcher, 1997, Malayocamallanus Jothy and Fernando, 1970, Procamallanus Baylis, 1922, Punctocamallanus Moravec and Scholz, 1991, Spirocamallanus Olsen, 1952, and Spirocamallanoides Moravec and Sey, 1988 (Fig. 2), distinguished by the presence/absence and morphology of internal ornamentations in the buccal capsule.

Figure 2. Illustrative drawings of buccal capsule morphology of the genera in the subfamily Procamallaninae Yeh, 1960. (A) Procamallanus; (B) Denticamallanus; (C) Punctocamallanus; (D) Malayocamallanus; (E) Spirocamallanus; (F) Spirocamallanoides.

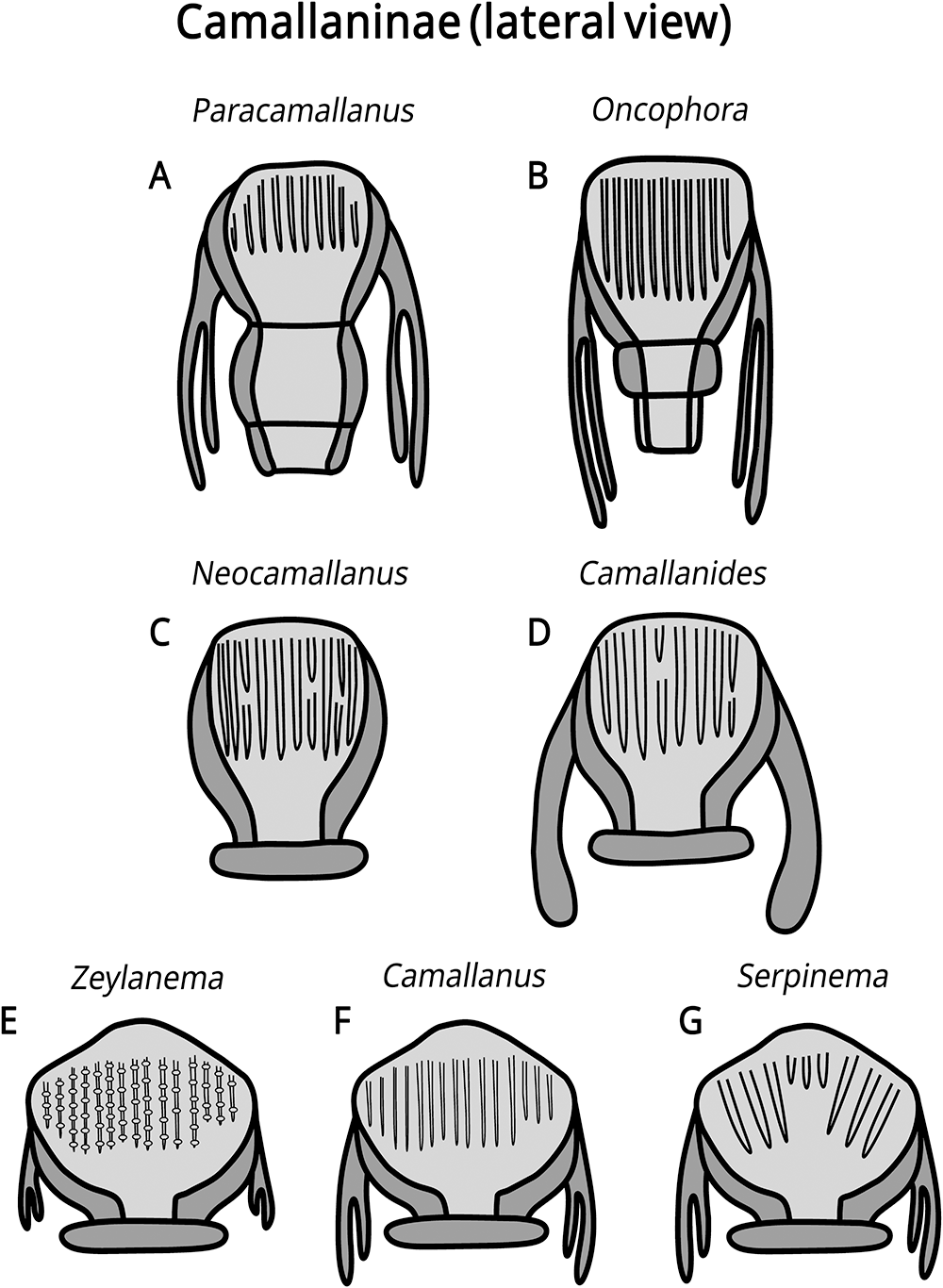

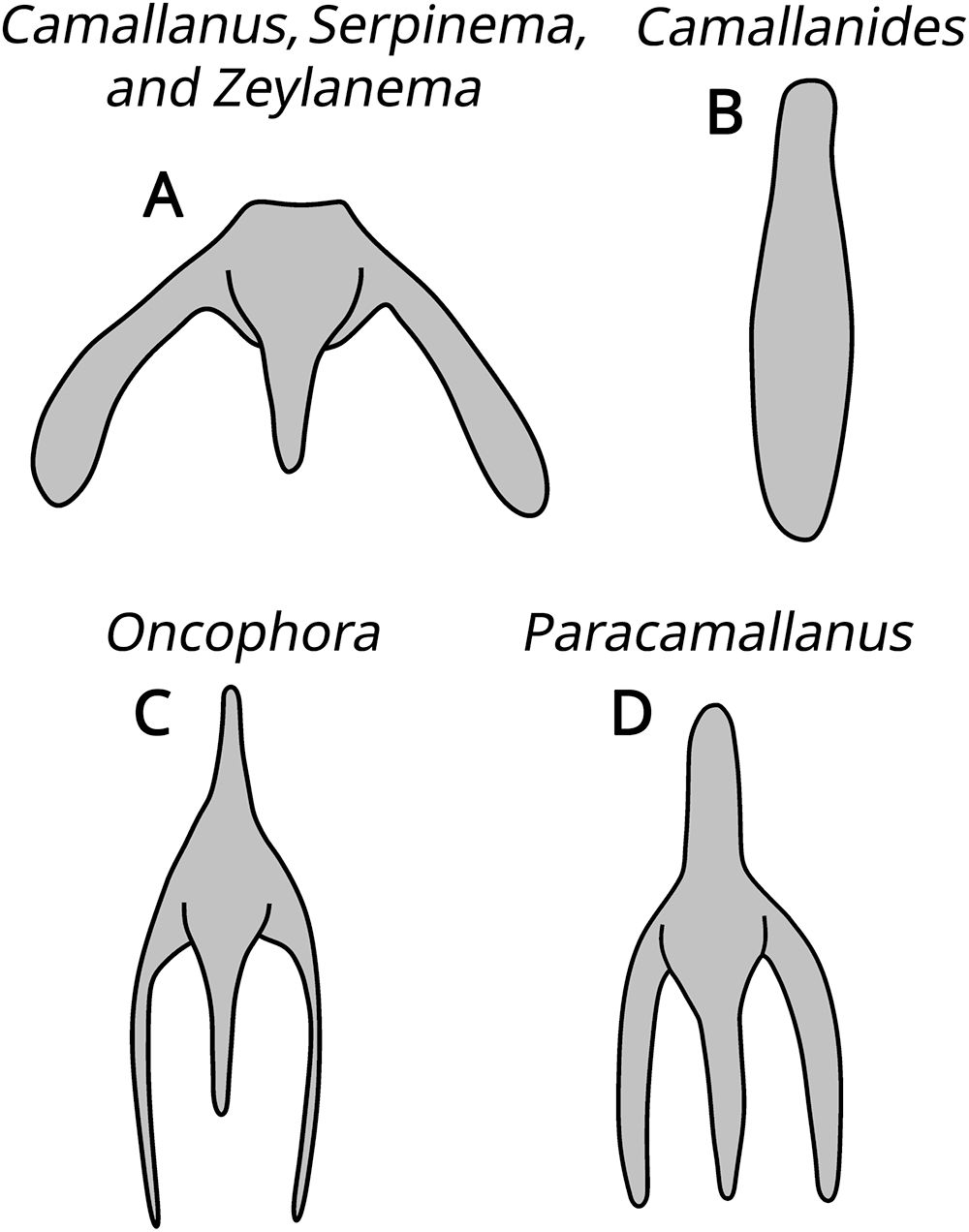

The subfamily Camallaninae (buccal capsule divided into 2 valves) is represented by the genera Camallanides Baylis and Daubney, 1922, Camallanus Railliet and Henry, 1915, Neocamallanus Ali, 1957, Oncophora Diesing, 1851, Paracamallanus Yorke and Maplestone, 1926, Serpinema Yeh, 1960, and Zeylanema Yeh, 1960 (Fig. 3). We can distinguish Oncophora and Paracamallanus because they have a buccal capsule divided into 3 chambers, as well as by the relative size of these chambers and the tridents morphology. Camallanus, Serpinema and Zeylanema are morphologically similar, sharing similar tridents, but we differentiate them by the morphology and distribution pattern of the internal ridges on the buccal capsule. Camallanides lacks tridents, whereas Neocamallanus possesses a trident composed of a single branch. Figure 4 illustrates the morphology of the tridents.

Figure 3. Illustrative drawings of buccal capsule morphology of the genera in the subfamily Camallaninae Yeh, 1960. (A) Paracamallanus; (B) Oncophora; (C) Neocamallanus; (D) Camallanides; (E) Zeylanema; (F) Camallanus; (G) Serpinema.

Figure 4. Illustrative drawings of the morphology of the tridents. (A) Camallanus, Serpinema and Zeylanema; (B) Camallanides; (C) Oncophora; (D) Paracamallanus.

We identified 37 species of Camallanidae in Brazil, belonging to 7 genera. Spirocamallanus was the most diverse genus, with 16 species. The species Sp. inopinatus (Travassos, Artigas and Pereira, 1928) showed the highest number of host records (144 hosts). In contrast, Procamallanus was the least diverse genus, and we found 10 camallanid species parasitizing only a single host species (Fig. 5). In total, we found records of 276 host taxa, comprising 265 fish, 10 chelonians and 1 snake. Among the 265 fish hosts, some were identified only to order (1), family (2), subfamily (2) or genus (16); 1 taxon corresponds to a hybrid species (Colossoma macropomum × Piaractus brachypomus), and 2 taxa the authors were unable to confirm the species. Additionally, 17 fish hosts, not included in the count above, were identified only by their local names, preventing the determination of host species. We did not find any records of camallanids in Brazilian amphibians. We also provide a table with all host taxa, organized by families (Table 1).

Figure 5. Diversity of Camallanidae taxa reported in Brazil, with the number of species per genus and the number of hosts per camallanid taxa.

Table 1. Records of vertebrate hosts of Camallanidae species reported in Brazil

Among the host families, the most frequent were Cichlidae (27 species), followed by Anostomidae (23 taxa) and Pimelodidae (21 taxa), from fish hosts. Among the chelonians, the family Chelidae has the highest number of species parasitized by camallanids, with 6 host species recorded to date in Brazil. Viperidae was the only snake family represented, with only 1 species recorded (Fig. 6).

Figure 6. Number of host taxa of camallanids by the host families in Brazil.

The North and Southeast regions of Brazil exhibited the highest diversity of Camallanidae, with 38 and 37 taxa reported, respectively. Among the Brazilian states, Pará (North) and São Paulo (Southeast) recorded the greatest number of taxa, with 15 and 14 species, respectively. Across Brazilian biomes, the Amazon exhibited the highest diversity of camallanids, with 22 taxa, followed by the Atlantic Forest (21), Cerrado (13), Caatinga (11), Pampa (6) and Pantanal (1).

Regarding host habitats, most camallanid species are associated with freshwater hosts, totalling 32 taxa. Marine and freshwater/terrestrial environments each harbour 6 taxa, whereas strictly terrestrial hosts contain only a single camallanid taxon.

Checklist of species of the family Camallanidae reported in Brazil

Camallanidae gen. sp.

Hosts: Arapaima gigas (Schinz, 1822), Brycon hilarii (Valenciennes, 1850), Pimelodus sp., Pygocentrus nattereri Kner, 1858.

Host environments: freshwater.

Sites of infection: intestine.

Locality records: Midwest: Mato Grosso; North: Acre; Southeast: São Paulo.

Biomes: Amazon, Atlantic Forest and Cerrado.

References: Travassos (Reference Travassos1940); Travassos and Freitas (Reference Travassos and Freitas1942); Silva et al. (Reference Silva, Pinto, Cavalcante, Santos, Moutinho and Santos2016).

Unconfirmed hosts: Astyanax bimaculatus (Linnaeus, 1758), Cyphocharax gilbert (Quoy and Gaimard, 1824), Moenkhausia doceana (Steindachner, 1877) in Luque et al. (Reference Luque, Aguiar, Vieira, Gibson and Santos2011).

Unconfirmed locality records: Espírito Santo (Southeast) in Luque et al. (Reference Luque, Aguiar, Vieira, Gibson and Santos2011).

Subfamily Procamallaninae Yeh, 1960

Genus Denticamallanus Moravec and Thatcher, 1997

Denticamallanus dentatus (Moravec and Thatcher, 1997)

Synonyms: Procamallanus (Denticamallanus) dentatus Moravec and Thatcher, 1997.

Hosts: Bryconops alburnoides Kner, 1858.

Host environments: freshwater.

Sites of infection: intestine.

Locality records: North: Amazonas.

Biomes: Amazon.

Specimens deposited: holotype, allotype and paratypes: INPA-NEM 007-010; paratypes HWML 39128; paratypes in the Institute of Parasitology, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, České Budějovice, Czech Republic, N–678.

References: Moravec and Thatcher (Reference Moravec and Thatcher1997).

Remarks: Denticamallanus was proposed as a subgenus of Procamallanus by Moravec and Thatcher (Reference Moravec and Thatcher1997), presenting as the main characteristic the presence of conical tooth-like structures in the posterior region of the buccal capsule in males and spiral ridges in females. By analysing records of other camallanid species, we observed that different species also present tooth-like structures, sometimes with sexual dimorphism. Therefore, our study considered the diagnostic characteristic for Denticamallanus to be the presence of conical tooth-like structures at the basal ring or in the posterior region of the buccal capsule of at least 1 sex, with spiral ridges that may or may not be present. These distinctive features, combined with the analyses of Ailán-Choke and Pereira (Reference Ailán-Choke and Pereira2021) (see Discussion), further support the recognition of Denticamallanus as a valid genus rather than a subgenus.

Denticamallanus annipetterae (Kohn and Fernandes, 1988)

Synonyms: Procamallanus annipetterae Kohn and Fernandes, 1988; Procamallanus (Procamallanus) annipetterae Kohn and Fernandes, 1988; Procamallanus petterae Kohn and Fernandes, 1988.

Hosts: Hypostomus albopunctatus (Regan, 1908) (=Plecostomus albopunctatus Regan, 1908), Hypostomus regani (Ihering, 1905), Hypostomus sp., Megalancistrus parananus (Peters, 1881).

Host environments: freshwater.

Sites of infection: intestine.

Locality records: South: Paraná.

Biomes: Atlantic Forest.

Specimens deposited: holotype: CHIOC 32430a, allotype: CHIOC 32430b.

References: Kohn and Fernandes (Reference Kohn and Fernandes1988a); Kohn et al. (Reference Kohn, Moravec, Cohen, Canzi, Takemoto and Fernandes2011).

Unconfirmed hosts: Hypostomus ternetzi (Boulenger, 1895) in Lehun et al. (Reference Lehun, Hasuike, Silva, Ciccheto, Michelan, Rodrigues, Nicola, Lima, Correia and Takemoto2020).

Remarks: Two different species of Procamallanus were proposed with the same name: Procamallanus (Procamallanus) patterae Moravec and Sey, 1988, described in Vietnam, and Procamallanus petterae Kohn and Fernandes, 1988, described in Brazil. Following the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, a new name for Pr. petterae Kohn and Fernandes, 1988, from Brazil, was proposed: Procamallanus annipetterae Kohn and Fernandes, 1988 (Kohn and Fernandes, Reference Kohn and Fernandes1988b).

Denticamallanus annipetterae (=Procamallanus annipetterae) was described with 5 tooth-like structures at the base of the buccal capsule and the absence of spiral ridges in both sexes. Additionally, we evaluated the allotype of the species (code CHIOC 32430b) and confirmed the characteristics of Denticamallanus. Therefore, we reallocated the species to the genus Denticamallanus, based on the new diagnostic criteria proposed (see key to genera of Procamallaninae).

Denticamallanus chimuensis (Freitas and Ibáñez, 1968)

Synonyms: Spirocamallanus chimuensis Freitas and Ibáñez, 1968; Procamallanus (Spirocamallanus) chimuensis (Freitas and Ibáñez, 1968); Procamallanus (Spirocamallanus) pexatus Pinto, Fabio, Noronha and Rolas, 1976; Procamallanus pexatus Pinto, Fabio, Noronha and Rolas, 1976; Spirocamallanus pexatus (Pinto, Fabio, Noronha and Rolas, 1976).

Hosts: Trichomycterus brasiliensis Lütken, 1874 (=Pygidium brasiliensis Eigenmann and Eigenmann, 1889).

Host environments: freshwater.

Sites of infection: intestine.

Locality records: Southeast: Espírito Santo.

Biomes: Atlantic Forest.

Specimens deposited: vouchers CHIOC 14228, 14233, 31086a-d, 31087, 31088a, 31088b, 31090a, 31089a-b, 31090b-c.

References: Pinto et al. (Reference Pinto, Fabio, Noronha and Rolas1976).

Remarks: This record refers to the study by Pinto et al. (Reference Pinto, Fabio, Noronha and Rolas1976), which described the species Procamallanus (Spirocamallanus) pexatus Pinto, Fabio, Noronha and Rolas, 1976. However, the species was subsequently synonymized with D. chimuensis (=Sp. chimuensis) by Moravec et al. (Reference Moravec, Chara and Shinn2004). In both studies, the authors describe the species as having spiral ridges in males and females. Moravec et al. (Reference Moravec, Chara and Shinn2004) also report the presence of 3 tooth-like structures in the buccal capsule of females. Despite not presenting in the description, the illustrations provided by Pinto et al. (Reference Pinto, Fabio, Noronha and Rolas1976) also show the presence of tooth-like structures in the buccal capsule of females. Therefore, we reallocated the species to the genus Denticamallanus.

Denticamallanus iheringi (Travassos, Artigas and Pereira, 1928)

Synonyms: Procamallanus iheringi Travassos, Artigas and Pereira, 1928; Spirocamallanus iheringi (Travassos, Artigas and Pereira, 1928); Procamallanus (Spirocamallanus) iheringi (Travassos, Artigas and Pereira, 1928).

Hosts: Hoplias malabaricus (Bloch, 1794), Hoplias aff. malabaricus, Hoplias sp., Hypomasticus copelandii (Steindachner, 1875) (=Leporinus copelandii Steindachner, 1875), Leporinus fasciatus (Bloch, 1794), Leporinus friderici (Bloch, 1794), Leporinus octofasciatus Steindachner, 1915, Leporinus sp., Megaleporinus elongatus (Valenciennes, 1850) (=Leporinus elongatus Valenciennes, 1850), Megaleporinus obtusidens (Valenciennes, 1837) (=Leporinus obtusidens (Valenciennes, 1837)), Salminus hilarii Valenciennes, 1850, Schizodon borelli (Boulenger, 1900), Schizodon fasciatus Spix and Agassiz, 1829, Schizodon nasutus Kner, 1858, Tetragonopterus sp., Zungaro zungaro (Humboldt, 1821) (=Pseudopimelodus zungaro (Humboldt, 1821)), Anostominae gen. sp., Tetragonopterinae gen. sp., Characidae gen. sp., ‘taguara’ or ‘cachimboré’ (local names).

Host environments: freshwater.

Sites of infection: intestine, pyloric cecum, pyloric diverticulum.

Locality records: South: Paraná; Southeast: Minas Gerais, São Paulo.

Biomes: Atlantic Forest and Cerrado.

Specimens deposited: type-material CHIOC 5875, vouchers CHIOC 14739, 16473-16478, 16480,16481, 16483-16488, 16490-16493, 16495, 16497-16505, 16508, 16511, 16514, 28837, 31063a-d, 31070a-b, 31319, 31320, 31321.

References: Travassos et al. (Reference Travassos, Artigas and Pereira1928); Travassos and Kohn (Reference Travassos and Kohn1965); Kohn and Fernandes (Reference Kohn and Fernandes1987); Pinto et al. (Reference Pinto, Fabio, Noronha and Rolas1975); Pinto and Noronha (Reference Pinto and Noronha1976); Moravec et al. (Reference Moravec, Kohn and Fernandes1993); Machado et al. (Reference Machado, Pavanelli and Takemoto1995); Machado et al. (Reference Machado, Pavanelli and Takemoto1996); Feltran et al. (Reference Feltran, Marçal Júnior, Pinese and Takemoto2004); Pavanelli et al. (Reference Pavanelli, Machado, Takemoto, Guidelli, Lizama, Thomaz, Agostinho and Hanh2004); Guidelli et al. (Reference Guidelli, Gomes Tavechio, Massato Takemoto and Pavanelli2006); Takemoto et al. (Reference Takemoto, Pavanelli, Lizama, Lacerda, Yamada, Moreira, Ceschini and Bellay2009); Kohn et al. (Reference Kohn, Moravec, Cohen, Canzi, Takemoto and Fernandes2011); Corrêa et al. (Reference Corrêa, Takemoto, Ueta and Adriano2020).

Unconfirmed hosts: Psalidodon fasciatus (Cuvier, 1819) (=Astyanax fasciatus (Cuvier, 1819)) in Luque et al. (Reference Luque, Aguiar, Vieira, Gibson and Santos2011); Megaleporinus piavussu (Britski, Birindelli and Garavello, 2012) in Lehun et al. (Reference Lehun, Hasuike, Silva, Ciccheto, Michelan, Rodrigues, Nicola, Lima, Correia and Takemoto2020).

Unconfirmed locality records: Espírito Santo (Southeast) in Luque et al. (Reference Luque, Aguiar, Vieira, Gibson and Santos2011).

Remarks: Pinto et al. (Reference Pinto, Fabio, Noronha and Rolas1975) redescribed D. iheringi (=Sp. iherengi) with illustrations that show the presence of tooth-like structures in the buccal capsule of females, although the authors did not report this in their description. Additionally, the authors indicate the codes 31070 a-b as the type material, but the type material registered and deposited in CHIOC is under code CHIOC 5857.

Moravec et al. (Reference Moravec, Kohn and Fernandes1993) also illustrate the presence of 6 tooth-like structures in the buccal capsule of females of D. ihering (=Sp. iherengi). Therefore, we reallocated the species to the genus Denticamallanus.

Denticamallanus krameri (Petter, 1974)

Synonyms: Spirocamallanus krameri Petter, 1974; Procamallanus (Spirocamallanus) krameri (Petter, Reference Petter1974).

Hosts: Bryconops cf. affinis, Hoplerythrinus unitaeniatus (Spix and Agassiz, 1829), Crenicichla brasiliensis (Bloch, 1792) (=Saxatilia brasiliensis (Bloch, 1792)).

Host environments: freshwater.

Sites of infection: middle intestine, pyloric cecum.

Locality records: North: Pará; Northeast: Maranhão.

Biomes: Amazon and Cerrado.

Specimens deposited: vouchers MPEG 0206, 0207, 0208, 0209, (Access number: 20190400001).

References: Pinheiro et al. (Reference Pinheiro, Cardoso, Monks, Santos and Giese2020); Pinheiro et al. (Reference Pinheiro, Teixeira, Tavares-Dias and Giese2021); Cárdenas et al. (Reference Cárdenas, Silva, Viana, Cohen and Ottoni2024).

Remarks: Denticamallanus krameri (=Sp. krameri) was described by Petter (Reference Petter1974) into the genus Spirocamallanus, based on only 1 male and 1 female specimen. The species was described parasitizing Hoplerythrinus uniateniatus in French Guiana. Moravec et al. (Reference Moravec, Prouza and Royero1997) present the first redescription of the species from specimens collected from the type host from Venezuela. Both studies report the presence of tooth-like structures only in males.

Pinheiro et al. (Reference Pinheiro, Cardoso, Monks, Santos and Giese2020) present a new redescription of D. krameri (=Sp. krameri), with the first record of this species in Brazil. The study includes scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis of the species but does not provide light microscopy (photomicrographs or line drawings), so there is no representation of the internal morphology of the buccal capsule. However, the authors report, in addition to spiral ridges in both sexes, 3 large teeth at the base of the basal ring in males, absent in females. Additionally, Cárdenas et al. (Reference Cárdenas, Silva, Viana, Cohen and Ottoni2024) also report spiral ridges in both sexes and the presence of 3 tooth-like structures at the base of the buccal capsule of males. Therefore, we reallocated the species to the genus Denticamallanus.

Denticamallanus rarus (Travassos, Artigas and Pereira, 1928)

Synonyms: Spirocamallanus rarus Travassos, Artigas and Pereira, 1928; Procamallanus rarus (Travassos, Artigas and Pereira, 1928); Procamallanus (Spirocamallanus) rarus (Travassos, Artigas and Pereira, 1928).

Hosts: Ageneiosus ucayalensis Castelnau, 1855, Pimelodella lateristriga (Lichtenstein, 1823), Pimelodus albicans (Valenciennes, 1840), Pimelodus blochii Valenciennes, 1840, Pimelodus maculatus Lacepède, 1803, Rhinodoras dorbignyi (Kner, 1855), Satanoperca jurupari (Heckel, 1840), Serrasalmus sp., Synodontis clarias (Linnaeus, 1758) (=Pimelodus clarias Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, 1809), ‘catfish’ (undetermined species).

Host environments: freshwater.

Sites of infection: intestine; small intestine.

Locality records: North: Acre, Pará; Southeast: São Paulo.

Biomes: Amazon, Atlantic Forest and Cerrado.

Specimens deposited: type material CHIOC 5930; vouchers CHIOC 6055, 26411, 26414, 31026-31029, 35717.

References: Travassos et al. (Reference Travassos, Artigas and Pereira1928); Travassos and Kohn (Reference Travassos and Kohn1965); Pinto et al. (Reference Pinto, Fabio, Noronha and Rolas1974); Kohn and Fernandes (Reference Kohn and Fernandes1987); Giese et al. (Reference Giese, Santos and Lanfredi2009); Melo et al. (Reference Melo, Santos, Giese, Santos and Santos2011); Negreiros et al. (Reference Negreiros, Pereira, Tavares-Dias and Tavares2018); Cavalcante et al. (Reference Cavalcante, Silva, Pereira, Gentile and Santos2020).

Unconfirmed hosts: Cichla piquiti Kullander and Ferreira, 2006 and Sorubim lima (Bloch and Schneider, 1801) in Lehun et al. (Reference Lehun, Hasuike, Silva, Ciccheto, Michelan, Rodrigues, Nicola, Lima, Correia and Takemoto2020).

Remarks: Moravec (Reference Moravec1998) states that the characterization of the spicule of D. rarus (=Sp. rarus) in the study by Travassos etal. (Reference Travassos, Artigas and Pereira1928) is inadequate and provides a more detailed description of this structure. Melo et al. (Reference Melo, Santos, Giese, Santos and Santos2011) presents a description of D. rarus (=Sp. rarus) that matches the description provided in Moravec (Reference Moravec1998). Thus, we reallocated the species to the genus Denticamallanus based on the illustrations from the studies by Pinto et al. (Reference Pinto, Fabio, Noronha and Rolas1974), Moravec (Reference Moravec1998) and Melo et al. (Reference Melo, Santos, Giese, Santos and Santos2011), which suggest the presence of 3 or 4 tooth-like structures in the buccal capsule of males.

Denticamallanus saofranciscensis (Moreira, Oliveira and Costa, 1994)

Synonyms: Spirocamallanus saofranciscensis Moreira, Oliveira and Costa, 1994; Procamallanus (Spirocamallanus) saofranciscencis (Moreira, Oliveira and Costa, 1994).

Hosts: Acestrorhynchus lacustris (Lütken, 1875), Astyanax bimaculatus, Leporinus piau Fowler, 1941, Moenkhausia costae (Steindachner, 1907), Moenkhausia intermedia Eigenmann, 1908, Oreochromis niloticus (Linnaeus, 1758), Psalidodon fasciatus (=Astyanax fasciatus), Serrapinnus heterodon (Eigenmann, 1915), Tetragonopterus chalceus Spix and Agassiz, 1829, Triportheus angulatus (Spix and Agassiz, 1829), Triportheus guentheri (Garman, 1890), Triportheus signatus (Garman, 1890).

Host environments: freshwater.

Sites of infection: coelomic cavity, intestinal cecum, intestine, mesentery, pyloric cecum, stomach.

Locality records: Northeast: Bahia, Ceará, Paraíba, Rio Grande do Norte; Southeast: Minas Gerais, São Paulo.

Biomes: Caatinga and Cerrado.

Specimens deposited: vouchers CHIOC 35578, 37857, 37858; voucher CHIBB 6815.

References: Moreira et al. (Reference Moreira, Oliveira and Costa1994); Abdallah et al. (Reference Abdallah, Azevedo, Carvalho and Silva2012); Albuquerque et al. (Reference Albuquerque, Santos-Clapp and Brasil-Sato2016); Laurentino E Silva et al. (Reference Laurentino E Silva, Cosme da Silva, Nascimento, Cavalcanti and Chellappa2017); Vieira-Menezes et al. (Reference Vieira-Menezes, Costa and Brasil-Sato2017); Duarte et al. (Reference Duarte, Santos-Clapp and Brasil-Sato2022a); Falkenberg et al. (Reference Falkenberg, De Lima, Yamada, Ramos and Lacerda2024); Sousa et al. (Reference Sousa, Falkenberg, Lima, Winkeler, Ramos, Lustosa-Costa, Menezes and Lacerda2025).

Unconfirmed specimens deposited: deposit codes CHIOC 39115, 39116 in Duarte et al. (Reference Duarte, Santos-Clapp and Brasil-Sato2022a).

Remarks: Moreira et al. (Reference Moreira, Oliveira and Costa1994) described D. saofranciscensis (=Sp. saofranciscensis) with 3 teeth at the base of the buccal capsule in males and females. Therefore, we reallocated the species to the genus Denticamallanus. The authors mention the deposit of the type material in CHIOC but do not provide the codes. Consulting the CHIOC online catalogue, none of the materials identified as ‘Spirocamallanus saofranciscensis’ refer to the material analysed by Moreira et al. (Reference Moreira, Oliveira and Costa1994). Additionally, the deposit codes CHIOC 39115 and 39116 provided in the study by Duarte et al. (Reference Duarte, Santos-Clapp and Brasil-Sato2022a) are not included in the CHIOC online catalogue.

We also analysed specimen vouchers of D. saofranciscensis (=Sp. saofranciscensis) (codes CHIOC 37857 and 37858) and confirmed the presence of tooth-like structures in both sexes.

Denticamallanus spiculastriatus (Pinheiro, Melo, Monks, Santos and Giese, 2018)

Synonyms: Procamallanus spiculastriatus Pinheiro, Melo, Monks, Santos and Giese, 2018.

Hosts: Astronotus ocellatus (Agassiz, 1831).

Host environments: freshwater.

Sites of infection: intestine.

Locality records: North: Pará.

Biomes: Amazon.

Specimens deposited: holotype MPEG 195, allotype MPEG 196, paratypes MPEG 197–200.

References: Pinheiro et al. (Reference Pinheiro, Melo, Monks, Santos and Giese2018); Pinheiro et al. (Reference Pinheiro, Tavares-Dias and Giese2019).

Remarks: Pinheiro et al. (Reference Pinheiro, Melo, Monks, Santos and Giese2018) described D. spiculastriatus (=Pr. spiculastriatus) with the inner surface of the buccal capsule smooth, without ridges, in both sexes. However, in the figures and discussion of the article, the authors indicate the presence of 4 tooth-like structures at the basal ring in both sexes. Therefore, we reallocated the species to the genus Denticamallanus.

Genus Procamallanus Baylis, 1923

Procamallanus peraccuratus Pinto, Fabio, Noronha and Rolas, 1976

Synonyms: Procamallanus (Procamallanus) peraccuratus Pinto, Fabio, Noronha and Rolas, 1976.

Hosts: Astyanax bimaculatus, Australoheros facetus (Jenyns, 1842) (=Cichlasoma facetum (Jenyns, 1842), Cichlaurus facetus (Jenyns, 1842)), Biotodoma cupido (Heckel, 1840), Cichla monoculus Agassiz, 1831, Cichla ocellaris Bloch and Schneider, 1801, Cichla piquiti, Crenicichla lepidota Heckel, 1840, Crenicichla niederleinii (Holmberg, 1891), Crenicichla sp., Geophagus brasiliensis (Quoy and Gaimard, 1824), Gymnotus carapo Linnaeus, 1758, Hoplias malabaricus, Hoplias aff. malabaricus, Laetacara flavilabris (Cope, 1870), Leporinus jamesi Garman, 1929, Pimelodus ortmanni Haseman, 1911, Potamorhina altamazonica (Cope, 1878), Potamotrygon motoro (Müller and Henle, 1841), Pygocentrus nattereri, Trachelyopterus galeatus (Linnaeus, 1766), Trachelyopterus striatulus (Steindachner, 1877).

Host environments: freshwater.

Sites of infection: intestine, mesentery, stomach.

Locality records: North: Acre; Amapá; Northeast: Paraíba; South: Paraná, Rio Grande do Sul; Southeast: Espírito Santo, Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo.

Biomes: Amazon, Atlantic Forest, Caatinga and Pampa.

Specimens deposited: holotype CHIOC 31084a, allotype 31084b, paratypes CHIOC 31078, 31079, 31080 a-b, 31081 a-b, 31082 a-b, 31083 a-d, 31084c, 31085, 16744-16749, 16751-16754, 16757-16776, 16853, 29446, 29472; vouchers CHIBB 4999, 5000, 5006, 5145.

References: Pinto et al. (Reference Pinto, Fabio, Noronha and Rolas1976); Kohn et al. (Reference Kohn, Fernandes, Pipolo and Godoy1988); Kohn et al. (Reference Kohn, Fernandes, Pipolo and Godoy1989); Welblen and Brandão (Reference Welblen and Brandão1992); Moravec et al. (Reference Moravec, Kohn and Fernandes1993); Pavanelli et al. (Reference Pavanelli, Machado, Takemoto, Guidelli, Lizama, Thomaz, Agostinho and Hanh2004); Takemoto et al. (Reference Takemoto, Pavanelli, Lizama, Lacerda, Yamada, Moreira, Ceschini and Bellay2009); Azevedo et al. (Reference Azevedo, Abdallah and Luque2010); Carvalho et al. (Reference Carvalho, Tavares and Luque2010); Bellay et al. (Reference Bellay, Uedal, Takemoto, Lizamal and Pavanelli2011); Kohn et al. (Reference Kohn, Moravec, Cohen, Canzi, Takemoto and Fernandes2011); Mesquita et al. (Reference Mesquita, Azevedo, Abdallah and Luque2011); Franceschini et al. (Reference Franceschini, Zago, Zocoller-Seno, Veríssimo-Silveira, Nunhaus-Silveira and Silva2013); Virgilio et al. (Reference Virgilio, Martins, Lima, Takemoto, Camargo and Meneguetti2022); Mota-Júnior et al. (Reference Mota-Júnior, Santos, Valentim, Oliveira and Tavares-Dias2024); De Lima et al. (Reference De Lima, Mendonça-Filho, Lima, Honório, Falkenberg, Yamada, Lustosa-Costa, Ramos, Teixeira de Mello, Menezes, Windsor and Lacerda2025).

Unconfirmed hosts: Schizodon nasutus in Luque et al. (Reference Luque, Aguiar, Vieira, Gibson and Santos2011); Hemisorubim platyrhynchos (Valenciennes, 1840), Hoplias spp. and Potamotrygon amandae Loboda and Carvalho, 2013 in Lehun et al. (Reference Lehun, Hasuike, Silva, Ciccheto, Michelan, Rodrigues, Nicola, Lima, Correia and Takemoto2020).

Remarks: Procamallanus peraccuratus was described from material previously deposited in CHIOC.

Mota-Júnior et al. (Reference Mota-Júnior, Santos, Valentim, Oliveira and Tavares-Dias2024) report ‘Spirocamallanus peraccuratus’ in Crenicichla strigata from Amapá State (North). However, this combination of names does not exist in literature. Based on the specific epithet ‘peraccuratus’ and its occurrence in Brazil, probably there was a mistake in the authors’ writing, and it refers to the species Pr. peraccuratus. This species is very well described and characterized as belonging to the genus Procamallanus, with no doubt so far regarding its taxonomic classification.

Procamallanus sp.

Hosts: Acestrorhynchus lacustris, Astyanax bimaculatus, Astyanax sp., Australoheros facetus, Brycon insignis Steindachner, 1877, Bryconops alburnoides, Calophysus macropterus (Lichtenstein, 1819), Cichlasoma amazonarum Kullander, 1983, Colossoma macropomum (Cuvier, 1816), Conorynchus conirostris (Valenciennes, 1840) (=Conostome conirostris Valenciennes, 1840), Genypterus brasiliensis Regan, 1903, Geophagus iporangensis Haseman, 1911, Hoplias malabaricus, Hypomasticus copelandii (=Leporinus copelandii), Iguanodectes spilurus (Günther, 1864), Leporinus octofasciatus, Leporinus striatus Kner, 1858, Leporinus sp., Menticirrhus americanus (Linnaeus, 1758), Mesonauta sp., Moenkhausia costae, Paracheirodon axelrodi (Schultz, 1956), Percophis brasiliensis Quoy and Gaimard, 1825, Pimelodus maculatus, Prionotus punctatus (Bloch, 1793), Prochilodus lineatus (Valenciennes, 1837) (=Prochilodus scrofa Steindachner, 1881), Psalidodon fasciatus (=Astyanax fasciatus), Pseudopercis numida Miranda Ribeiro, 1903, Pseudopercis semifasciata (Cuvier, 1829), Pygocentrus nattereri, Rhinodoras dorbignyi, Salminus hilarii, Sarda sarda (Bloch, 1793), Schizodon altoparanae Garavello and Britski, 1990, Synodontis clarias (=Pimelodus clarias), Trachydoras paraguayensis (Eigenmann and Ward, 1907), Trichiurus lepturus Linnaeus, 1758, Triportheus nematurus (Kner, 1858) (=Chalcinus nematurus Kner, 1858), Triportheus guentheri, Characidae gen. sp., Doradidae gen. sp., Tetragonopterinae gen. sp., Siluriformes fam. gen. sp., ‘jatuarama’, ‘cará-cahimbo’, ‘ferreirinha’, ‘linguadinho’, ‘peixe-cachorro’, ‘tabarana’, ‘taguara’ or ‘chimboré’ (local names).

Host environments: freshwater and marine.

Sites of infection: intestine, large intestine, mesentery, pyloric diverticulum, small intestine, stomach.

Locality records: Midwest: Mato Grosso; North: Amapá, Amazonas, Pará; Northeast: Maranhão, Paraíba; South: Paraná; Southeast: Espírito Santo, Minas Gerais; Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo.

Biomes: Amazon, Atlantic Forest and Caatinga.

Specimens deposited: CHIOC 8625, 8629, 8650, 8752, 8816, 8817, 8829, 12273, 12283, 14722, 14723, 14734, 14738, 14751, 14763, 16482, 16489, 16494, 16512, 16519, 16520, 16521, 16777, 16789, 16792, 16799, 16788, 16794, 16798, 26494, 28439, 28444, 28452, 28475, 28476, 28477, 28478, 28629, 30804a-b, 31313, 31314a-b, 31344, 31345, 31346a-b, 34653, 35350, 35461, 35577.

References: Travassos and Freitas (Reference Travassos and Freitas1940); Travassos and Freitas (Reference Travassos and Freitas1948); Travassos and Freitas (Reference Travassos and Freitas1964); Vicente and Santos (Reference Vicente and Santos1973); Pinto et al. (Reference Pinto, Fabio, Noronha and Rolas1975); Pinto and Noronha (Reference Pinto and Noronha1976); Kohn et al. (Reference Kohn, Fernandes, Macedo and Abramson1985); Kohn and Fernandes (Reference Kohn and Fernandes1987); Kohn et al. (Reference Kohn, Fernandes, Pipolo and Godoy1988); Silva et al. (Reference Silva, Luque, Alves and Paraguassú2000); Alves et al. (Reference Alves, Luque and Paraguassú2002); Carvalho et al. (Reference Carvalho, Guidelli, Takemoto and Pavanelli2003); Fischer et al. (Reference Fischer, Malta and Varella2003); Pavanelli et al. (Reference Pavanelli, Machado, Takemoto, Guidelli, Lizama, Thomaz, Agostinho and Hanh2004); Bicudo et al. (Reference Bicudo, Tavares and Luque2005); Alves and Luque (Reference Alves and Luque2006); Fernandes et al. (Reference Fernandes, Pereira, Matos Júnior and Souza2006); Santos et al. (Reference Santos, Castro and Brasil-Sato2007); Luque et al. (Reference Luque, Felizardo and Tavares2008); Takemoto et al. (Reference Takemoto, Pavanelli, Lizama, Lacerda, Yamada, Moreira, Ceschini and Bellay2009); Tavares-Dias et al. (Reference Tavares-Dias, Brito and Lemos2009); Azevedo et al. (Reference Azevedo, Abdallah and Luque2010); Barros et al. (Reference Barros, Mateus, Braum and Bonaldo2010); Tavares-Dias et al. (Reference Tavares-Dias, Lemos and Martins2010); Benigno et al. (Reference Benigno, São Clemente, Matos, Pinto, Gomes and Knoff2012); Fujimoto et al. (Reference Fujimoto, Anjos, Ramos and Martins2013); Bittencourt et al. (Reference Bittencourt, Pinheiro, Cárdenas, Fernandes and Tavres-Dias2014); Albuquerque et al. (Reference Albuquerque, Santos-Clapp and Brasil-Sato2016); Vieira-Menezes et al. (Reference Vieira-Menezes, Costa and Brasil-Sato2017); Cárdenas et al. (Reference Cárdenas, Justo, Reyes and Cohen2022); Moraes et al. (Reference Moraes, Costa, Takemoto and Padial2024); De Lima et al. (Reference De Lima, Mendonça-Filho, Lima, Honório, Falkenberg, Yamada, Lustosa-Costa, Ramos, Teixeira de Mello, Menezes, Windsor and Lacerda2025); Sousa et al. (Reference Sousa, Falkenberg, Lima, Winkeler, Ramos, Lustosa-Costa, Menezes and Lacerda2025).

Unconfirmed hosts: Brevoortia aurea (Spix and Agassiz, 1829), Hemiodus sp., Megaleporinus macrocephalus (=Leporinus macrocephalus Garavello and Britski, 1988) (Garavello and Britski, 1988), Pimelodus blochii, Serrasalmus marginatus Valenciennes, 1837, and Serrasalmus spilopleura Kner, 1858 in Eiras et al. (Reference Eiras, Velloso and Pereira2016).

Remarks: All the studies mentioned identified camallanids only at the genus level. However, many authors used, and still use, the subgeneric classification for the genus Procamallanus. Therefore, these specimens identified as ‘Procamallanus sp.’ may belong to other genera in the family, especially Spirocamallanus.

Genus Spirocamallanus Olsen, 1952

Spirocamallanus amarali (Vaz and Pereira, 1934)

Synonyms: Procamallanus amarali Vaz and Pereira, 1934; Procamallanus (Spirocamallanus) amarali Vaz and Pereira, 1934.

Hosts: Hoplias aff. malabaricus, Leporinus sp., Leporinus friderici, Megaleporinus elongatus (=Leporinus elongatus), Megaleporinus obtusidens (=Leporinus obtusidens).

Host environments: freshwater.

Sites of infection: anterior intestine, cecum, intestine, middle intestine, pyloric diverticulum.

Locality records: South: Paraná; Southeast: São Paulo.

Biomes: Atlantic Forest and Cerrado.

Specimens deposited: CHIOC 16506, 31064a-r.

References: Vaz and Pereira (Reference Vaz and Pereira1934); Kohn and Fernandes (Reference Kohn and Fernandes1987); Pinto et al. (Reference Pinto, Fabio, Noronha and Rolas1975); Guidelli et al. (Reference Guidelli, Gomes Tavechio, Massato Takemoto and Pavanelli2006); Takemoto et al. (Reference Takemoto, Pavanelli, Lizama, Lacerda, Yamada, Moreira, Ceschini and Bellay2009); Corrêa et al. (Reference Corrêa, Takemoto, Ueta and Adriano2020).

Unconfirmed hosts: Hypomasticus copelandii (=Leporinus copelandii) in Luque et al. (Reference Luque, Aguiar, Vieira, Gibson and Santos2011); Megaleporinus piavussu in Lehun et al. (Reference Lehun, Hasuike, Silva, Ciccheto, Michelan, Rodrigues, Nicola, Lima, Correia and Takemoto2020).

Remarks: Pinto et al. (Reference Pinto, Fabio, Noronha and Rolas1975) described the female of Sp. amarali for the first time and redescribed the male of the species.

Spirocamallanus belenensis (Giese, Santos and Lanfredi, 2009)

Synonyms: Procamallanus belenensis Giese, Santos and Lanfredi, 2009; Procamallanus (Spirocamallanus) belenensis Giese, Santos and Lanfredi, 2009.

Hosts: Ageneiosus ucayalensis.

Host environments: freshwater.

Sites of infection: abdominal cavity, intestine.

Locality records: North: Amapá, Pará.

Biomes: Amazon.

Specimens deposited: type material CHIOC 35604a-c.

References: Giese et al. (Reference Giese, Santos and Lanfredi2009); Ferreira and Tavares-Dias (Reference Ferreira and Tavares-Dias2017).

Remarks: Spirocamallanus belenensis was described by Giese et al. (Reference Giese, Santos and Lanfredi2009) into the genus Procamallanus, subgenus Spirocamallanus, due to the presence of spiral ridges in buccal capsule of both sexes. However, currently the genus status of Spirocamallanus is accepted (Ailán-Choke and Pereira, Reference Ailán-Choke and Pereira2021). Therefore, we considered the species belonging to genus Spirocamallanus.

Spirocamallanus caballeroi Bashirullah, 1977

Synonyms: Spirocamallanus dessetae Petter, Golvan and Tcheprakoff, 1977.

Hosts: Astyanax altiparanae Garutti and Britski, 2000.

Host environments: freshwater.

Sites of infection: not provided.

Locality records: South: Paraná.

Biomes: Atlantic Forest.

References: Pavanelli et al. (Reference Pavanelli, Machado, Takemoto, Guidelli, Lizama, Thomaz, Agostinho and Hanh2004); Takemoto et al. (Reference Takemoto, Pavanelli, Lizama, Lacerda, Yamada, Moreira, Ceschini and Bellay2009).

Unconfirmed hosts: Astyanax lacustris (Lütken, 1874) in Lehun et al. (Reference Lehun, Hasuike, Silva, Ciccheto, Michelan, Rodrigues, Nicola, Lima, Correia and Takemoto2020).

Spirocamallanus delirae Ruffeil, Giese and Pinheiro, 2023

Hosts: Propimelodus eigenmanni (Van der Stigchel, 1946).

Host environments: freshwater.

Sites of infection: intestine.

Locality records: North: Pará.

Biomes: Amazon.

Specimens deposited: holotype MPEG 0277, allotype MPEG 0278, paratypes MPEG 0279, 0280.

References: Ruffeil et al. (Reference Ruffeil, Giese and Pinheiro2023).

Spirocamallanus freitasi Moreira, Oliveira and Costa, 1991

Hosts: Bergiaria westermanni (Lütken, 1874), Pimelodus maculatus, Pimelodus pohli Ribeiro and Lucena, 2006, Pimelodus sp.

Host environments: freshwater.

Sites of infection: intestine.

Locality records: Southeast: Minas Gerais.

Biomes: Cerrado.

Specimens deposited: vouchers CHIOC 35920, 35921.

References: Moreira et al. (Reference Moreira, Oliveira and Costa1991); Sabas and Brasil-Sato (Reference Sabas and Brasil-Sato2014).

Remarks: Moreira et al. (Reference Moreira, Oliveira and Costa1991) state that the type material was deposited in CHIOC, but they do not provide the codes. Additionally, Moravec (Reference Moravec1998) considers the species to be very similar to Spirocamallanus solani (Pinto, Fabio, Noronha and Rolas, Reference Pinto, Fabio, Noronha and Rolas1975.

Spirocamallanus freitasi has 17–19 spiral ridges on the buccal capsule of both sexes. Males have 9 pairs of caudal papillae (3 precloacal pairs, 1 ad-cloacal pair and 5 postcloacal pairs) and 2 unequal and dissimilar spicules. The large spicule is bifid with unequal parts: the larger part is ‘undigitated’ while the smaller part is bifid at the extremity; the smaller spicule is sharply ended (Moreira et al., Reference Moreira, Oliveira and Costa1991). Spirocamallanus solani has 12 spiral ridges in males and 17 spiral ridges in females; males have 9 pairs of caudal papillae (2 precloacal, 2 ad-cloacal and 5 postcloacal pairs); 2 unequal spicules with narrow alae and a simple morphology (Pinto et al., Reference Pinto, Fabio, Noronha and Rolas1975). Therefore, we consider Sp. freitasi and Sp. solani to have unique morphological characteristics and validate the species as distinct taxa.

Spirocamallanus halitrophus Fusco and Overstreet, 1978

Hosts: Citharichthys macrops Dresel, 1885, Mullus argentinae Hubbs and Marini, 1933, Paralichthys isosceles Jordan, 1891, Syacium papillosum (Linnaeus, 1758), Urophycis brasiliensis (Kaup, 1858), Xystreurys rasile (Jordan, 1891).

Host environments: marine.

Sites of infection: intestine.

Locality records: South: Rio Grande do Sul, Santa Catarina; Southeast: Rio de Janeiro.

Biomes: Atlantic Forest and Pampa.

Specimens deposited: CHIOC 35312-35314, 38336-38337, 38724-38735.

References: Cárdenas and Lanfredi (Reference Cárdenas and Lanfredi2005); Cárdenas et al. (Reference Cárdenas, De Souza and Lanfredi2005); Cárdenas et al. (Reference Cárdenas, Lanfredi and Olievira-Menezes2012); Pereira et al. (Reference Pereira, Pantoja, Luque and Timi2014); Di Azevedo and Iñiguez (Reference Di Azevedo and Iñiguez2018); Fonseca et al. (Reference Fonseca, Felizardo, Torres, Gomes and Knoff2022).

Remarks: Spirocamallanus halitrophus was described parasitizing Syacium papillosum in the Gulf of Mexico, and Cárdenas and Lanfredi (Reference Cárdenas and Lanfredi2005) reported for the first time the species in Brazil, provenient from the type host and Citharichthys macrops, both from the family Cyclopsettidae. The authors also presented the first SEM analysis of Sp. halitrophus.

Spirocamallanus hilarii (Vaz and Pereira, 1934)

Synonyms: Procamallanus hilarii Vaz and Pereira, 1934; Procamallanus (Spirocamallanus) hilarii Vaz and Pereira, 1934; Procamallanus cearensis Pereira, Dias and Azevedo, 1936; Spirocamallanus cearensis (Pereira, Dias and Azevedo, 1936); Spirocamallanus incarocai Freitas and Ibañez, 1970.

Hosts: Acestrorhynchus lacustris, Acestrorhynchus microlepis (Jardine, 1841), Astyanax bimaculatus (=Astyanax bimaculatus vittatus), Astyanax jacuhiensis (Cope, 1824), Cichla monoculus, Crenicichla brasiliensis (=Saxatilia brasiliensis), Geophagus brasiliensis, Hoplias lacerdae Miranda Ribeiro, 1908, Hoplias malabaricus, Hoplias aff. malabaricus, Hypostomus commersoni Valenciennes, 1836 (=Plecostomus commersoni (Valenciennes, 1836)), Moenkhausia intermedia, Oligosarcus macrolepis (Steindachner, 1877) (=Acestrorhamphus macrolepis Steindachner, 1877), Prochilodus brevis Steindachner, 1875, Psalidodon fasciatus (=Astyanax fasciatus), Psalidodon aff. fasciatus (=Astyanax aff. fasciatus), Psalidodon parahybae (Eigenmann, 1908) (=Astyanax parahybae Eigenmann, 1908), Psalidodon schubarti (Britski, 1964), (=Astyanax bimaculatus schubarti (Britski, 1964)), Rhamdia quelen (Quoy and Gaimard, 1824), Salminus hilarii, Serrapinnus heterodon, Serrapinus piaba (Lutken, 1875), Steindachnerina elegans (Steindachner, 1875 (=Curimatus elegans (Steindachner, 1875), Pseudocurimata elegans), Trichomycterus punctulatus Valenciennes, 1846 (=Pygidium punctulatum (Valenciennes, 1846)), Triportheus signatus, ‘lambari amarela’ and ‘lambari de cauda vermelha’ (undetermined species).

Host environments: freshwater.

Sites of infection: body cavity, eyes, gills, gonads, intestinal cecum, intestine, kidney, mesentery, stomach, pyloric cecum.

Locality records: Northeast: Ceará, Paraíba; South: Paraná, Rio Grande do Sul; Southeast: Minas Gerais, Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo.

Biomes: Atlantic Forest, Caatinga and Pampa.

Specimens deposited: type material in the Helminthological Collection of the Biological Institute of São Paulo, numbers 244-A e 244-B; vouchers CHIOC 29986 a-b, 31318, 31341a-d, 31347, 32360, 32361-32364, 32366-32371, 32373, 32374, 32379, 32380, 32383, 32384, 32387, 32388, 32451, 32522 a-f, 32525, 32526 a-d, 32528, 35289, 35290, 35948.

References: Vaz and Pereira (Reference Vaz and Pereira1934); Pereira et al. (Reference Pereira, Vianna and Azevedo1936); Kloss (Reference Kloss1966); Pinto and Noronha (Reference Pinto and Noronha1976); Kohn and Fernandes (Reference Kohn and Fernandes1987); Kohn et al. (Reference Kohn, Fernandes, Pipolo and Godoy1988); Kohn et al. (Reference Kohn, Fernandes, Pipolo and Godoy1989); Rodrigues et al. (Reference Rodrigues, Pinto and Noronha1991); Welblen and Brandão (Reference Welblen and Brandão1992); Abdallah et al. (Reference Abdallah, Azevedo and Luque2004); Azevedo et al. (Reference Azevedo, Abdallah and Luque2010); Gallas et al. (Reference Gallas, Calegaro-Marques and Bencke-Amato2015); Corrêa et al. (Reference Corrêa, Takemoto, Ueta and Adriano2020); Duarte et al. (Reference Duarte, Santos-Clapp and Brasil-Sato2022a); Falkenberg et al. (Reference Falkenberg, De Lima, Yamada, Ramos and Lacerda2024); De Lima et al. (Reference De Lima, Mendonça-Filho, Lima, Honório, Falkenberg, Yamada, Lustosa-Costa, Ramos, Teixeira de Mello, Menezes, Windsor and Lacerda2025); Silva et al. (Reference Silva, Falkenberg and Yamada2025).

Unconfirmed hosts: Trichomycterus piurae (Eigenmann, 1922) in Luque et al. (Reference Luque, Aguiar, Vieira, Gibson and Santos2011); Brycon orbignyanus (Valenciennes, 1850) and Hemisorubim platyrhynchos in Lehun et al. (Reference Lehun, Hasuike, Silva, Ciccheto, Michelan, Rodrigues, Nicola, Lima, Correia and Takemoto2020).

Unconfirmed specimens deposited: deposit codes vouchers CHIOC 39117 and 39118 in Duarte et al. (Reference Duarte, Santos-Clapp and Brasil-Sato2022a).

Remarks: Spirocamallanus hilarii was redescribed by Pinto and Noronha (Reference Pinto and Noronha1976) from material deposited in CHIOC. Rodrigues et al. (Reference Rodrigues, Pinto and Noronha1991) also redescribed the species based on specimens deposited in CHIOC and Instituto Biológico Helminthological Collection (CHIB) and compared data from specimens in previous studies related to the species Procamallanus cearensis Pereira, Dias and Azevedo, 1936, Spirocamallanus incarocai Freitas and Ibañez, 1970 and Sp. hilarii from both original description by Vaz and Pereira (Reference Vaz and Pereira1934) and redescription made by Pinto and Noronha (Reference Pinto and Noronha1976). Procamallanus cearensis was previously synonymized with Sp. hilarii and Rodrigues et al. (Reference Rodrigues, Pinto and Noronha1991) also synonymized Sp. incarocai with Sp. hilarii. However, there is disagreement regarding the number of caudal papillae and ridges on the buccal capsule between these specimens.

Procamallanus cearensis has 13–18 spiral ridges in both sexes and the males have 7 pairs of caudal papillae (4 precloacal pairs and 3 postcloacal pairs), while Sp. incarocai has 14 and 16 spiral ridges in males and females, respectively, and males with 9 pairs of caudal papillae (4 precloacal pairs, 1 ad-cloacal and 4 postcloacal) (Rodrigues et al., Reference Rodrigues, Pinto and Noronha1991). However, Sp. hilarii from original description by Vaz and Pereira (Reference Vaz and Pereira1934) has 16 spiral ridges in both sexes and males with 8 pairs of caudal papillae (3 precloacal, 2 ad-cloacal and 3 postcloacal); and despite the differences in number and distribution of caudal papillae, all these 3 species have 2 short and subequal spicules with similar morphometry. Thus, until these species are revised, the synonymizing should be maintained.

Spirocamallanus inopinatus (Travassos, Artigas and Pereira, 1928)

Synonyms: Procamallanus inopinatus Travassos, Artigas and Pereira, 1928; Procamallanus (Spirocamallanus) inopinatus Travassos, Artigas and Pereira, 1928; Procamallanus fariasi Pereira, 1934; Spirocamallanus fariasi (Pereira, 1934); Procamallanus probus Pinto and Fernandes, 1972; Procamallanus wrighti Pereira, 1935.

Hosts: Acestrorhynchus falcatus (Bloch, 1974), Acestrorhynchus falcirostris (Cuvier, 1819), Acestrorhynchus heterolepis (Cope, 1878), Acestrorhynchus lacustris, Ageneiosus inermis (Linnaeus, 1766), Ageneiosus sp., Anodus orinocensis (Steindachner, 1887), Anostomoides passionis Santos and Zuanon, 2006, Amblydoras affinis (Kner, 1855), Aphanotorulus emarginatus (Valenciennes, 1840) (=Squaliforma emarginta Valenciennes, 1840, Squaliforma squalina (Jardine, 1841)), Arapaima gigas, Astronotus ocellatus, Astyanax altiparanae, Astyanax bimaculatus, Astyanax lacustris (=Astyanax bimaculatus lacustris (Lütken, 1874)), Astyanax sp., Auchenipterichthys coracoideus (Eigenmann and Allen, 1942), Auchenipterichthys thoracatus (Kner, 1858), Auchenipterus ambyiacus Fowler, 1915, Auchenipterus brachyurus (Cope, 1878), Auchenipterus nuchalis (Spix and Agassiz, 1829), Biotodoma cupido, Brachychalcinus copei (Steindachner, 1882), Brycon amazonicus (Spix and Agassiz, 1829), Brycon cephalus (Günther, 1869) (=Brycon erythropterum (Cope, 1872)), Brycon falcatus Müller and Troschel (=Brycon brevicaudatus Günther, 1864), Brycon hilarii (Valenciennes, 1850), Brycon orbignyanus, Brycon sp., Bryconops caudomaculatus (Günther, 1864), Bryconops melanurus (Bloch, 1974), Calophysus macropterus, Catathyridium jenynsii (Günther, 1862), Chalceus epakros Zanata and Toledo-Piza, 2004, Charax pauciradiatus (Günther, 1864), Cheirocerus eques Eigenmann, 1917, Cheirodon jaguaribensis Fowler, 1941, Cichla kelberi Kullander and Ferreira, 2006, Cichla monoculus, Cichla nigromaculata Jardine and Schomburgk, 1843, Cichla sp., Cichlasoma bimaculatum (Linnaeus, 1758), Colossoma macropomum, Colossoma macropomum × Piaractus brachypomus (hybrid fish), Corydoras amapaensis Nijssen, 1972, Corydoras ephippifer Nijssen, 1972, Corydoras melanistius Regan, 1912, Corydoras spilurus Norman, 1926, Crenicichla haroldoi Luengo and Britski, 1974, Crenicichla sp., Ctenobrycon sp., Curimatella dorsalis (Eigenmann and Eigenmann, 1889), Curimatella sp., Cynodon gibbus (Agassiz, 1829), Eleotris pisonis (Gmelin, 1789), Epapterus dispilurus Cope, 1878, Erythrinus erythrinus (Bloch and Schneider, 1801), Galeocharax humeralis (Valenciennes, 1834) (=Cynopotamus humeralis Valenciennes, 1834), Geophagus altifrons Heckel, 1840, Hemiodus microlepis Kner, 1858, Hemiodus unimaculatus (Bloch, 1974), Heros severus Heckel, 1840, Hoplerythrinus unitaeniatus, Hoplias malabaricus, Hoplias aff. malabaricus, Hyphessobrycon takasei Géry, 1964, Hypomasticus copelandii (=Leporinus copelandii), Leporellus vittatus (Valenciennes, 1850), Leporinus fasciatus, Leporinus friderici, Leporinus jamesi, Leporinus lacustris (Amaral Campos, 1945), Leporinus moralesi Fowler, 1942, Leporinus piau, Leporinus striatus, Leporinus taeniatus Lütken, 1875, Leporinus sp., Megaleporinus elongatus (=Leporinus elongatus), Megaleporinus macrocephalus (=Leporinus macrocephalus), Megaleporinus obtusidens (=Leporinus obtusidens), Megaleporinus reinhardti (Lütken, 1875) (=Leporinus reinhardti Lütken, 1875), Mesonauta festivus (Heckel, 1840), Metynnis hypsauchen (Müller and Troschel, 1844), Metynnis lippincottianus (Cope, 1870), Metynnis luna Cope, 1878, Moenkhausia intermedia, Myloplus arnoldi Ahl, 1936, Myloplus asterias (Müller and Troschel, 1844), Myloplus rubripinnis (Müller and Troschel, 1844), Mylossoma duriventre (Cuvier, 1818), Nemadoras humeralis (Kner, 1855), Ossancora asterophysa Birindelli and Sabaj Pérez, 2011, Pimelodina flavipinnis Steindachner, 1876, Pimelodus blochii, Pimelodus ornatus Kner, 1858, Pimelodus pictus Steindachner, 1876, Pimelodus sp., Platydoras costatus (Linnaeus, 1758), Potamorhina altamazonica, Potamotrygon motoro, Prochilodus lineatus, Prochilodus nigricans Spix and Agassiz, 1829, Proloricaria prolixa (Isbrücker and Nijssen, 1978) (=Loricaria prolixa Isbrücker and Nijssen, 1978), Propimelodus caesius Parisi, Lundberg and DoNascimiento, 2006, Psalidodon fasciatus, Psalidodon schubarti (=Astyanax bimaculatus schubarti), Pterodoras granulosus (Valenciennes, 1821), Pygocentrus nattereri, Pygocentrus piraya (Cuvier, 1819), Rhaphiodon vulpinus Spiz and Agassiz, 1829, Roeboides myersii Gill, 1870, Roeboides sp., Salminus brasiliensis (Cuvier, 1816), Satanoperca jurupari, Schizodon borelli, Schizodon fasciatus, Schizodon knerii (Steindachner, 1875), Schizodon nasutus, Semaprochilodus insignis (Jardine, 1841), Serrasalmus altispinis Merckx, Jégu and Santos, 2000, Serrasalmus brandtii Lütken, 1875, Serrasalmus eigenmanni Norman, 1929, Serrasalmus maculatus Kner, 1858, Serrasalmus marginatus, Serrasalmus rhombeus (Linnaeus, 1766), Serrasalmus spilopleura, Serrapinnus heterodon, Sorubim lima, Steindachnerina bimaculata (Steindachner, 1876), Sternarchella schotti (Steindachner, 1868), Tetragonopterus argenteus Cuvier, 1816, Tetragonopterus chalceus, Thoracocharax stellatus (Kner, 1858), Trachelyopterus galeatus, Trachydoras paraguayensis, Triportheus angulatus, Triportheus auritus (Valenciennes, 1850), Triportheus curtus (Garman, 1890), Triportheus elongatus (Günther, 1864), Triportheus rotundatus (Jardine, 1841), Triportheus signatus, Triportheus trifurcatus (Castelnau, 1855), ‘lambari de rabo amarelo’, ‘piau’ (local names).

Host environments: freshwater.

Sites of infection: abdominal cavity, intestinal cecum, intestine, liver, mesentery, stomach, swim bladder, pyloric diverticulum.

Locality records: Midwest: Goiás, Mato Grosso, Mato Grosso do Sul; North: Acre, Amapá, Amazonas, Pará, Rondônia; Northeast: Bahia, Ceará, Maranhão, Paraíba, Piauí; South: Paraná; Southeast: Espírito Santo, Minas Gerais, Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo.

Biomes: Amazon, Atlantic Forest, Caatinga, Cerrado and Pantanal.

Specimens deposited: CHIOC 11463, 11467, 11468, 11471, 11473, 13055, 14634, 14644, 14652, 14762, 14729, 16496, 16506, 16509, 16645, 16525, 16575, 16800, 19743, 28460, 28474, 30601a-c, 30614a-f, 30644a-d, 31064a-r, 31091-31095, 31096a-b, 31097, 31315a-b, 31316a-c, 31324, 31325, 31326a-b, 31329, 31332, 31335, 31336a-c, 31337, 31338a-b, 31339a-b, 31343, 31348, 33331, 35556, 36950, 39133-39138, 39134, 39353, 39354; CHIBB 5008, 6809, 6813, 7871, 7954; INPA 057, 79, 80.

References: Travassos and Kohn (Reference Travassos and Kohn1965); Kloss (Reference Kloss1966); Kohn et al. (Reference Kohn, Fernandes, Macedo and Abramson1985); Kohn and Fernandes (Reference Kohn and Fernandes1987); Pinto et al. (Reference Pinto, Fabio, Noronha and Rolas1975); Pinto and Noronha (Reference Pinto and Noronha1976); Pinto et al. (Reference Pinto, Fabio, Noronha and Rolas1976); Petter and Thatcher (Reference Petter and Thatcher1988); Moravec et al. (Reference Moravec, Kohn and Fernandes1993); Moreira et al. (Reference Moreira, Oliveira and Costa1994); Machado et al. (Reference Machado, Pavanelli and Takemoto1995); Machado et al. (Reference Machado, Pavanelli and Takemoto1996); Andrade et al. (Reference Andrade, Malta and Ferraz2001); Feltran et al. (Reference Feltran, Marçal Júnior, Pinese and Takemoto2004); Pavanelli et al. (Reference Pavanelli, Machado, Takemoto, Guidelli, Lizama, Thomaz, Agostinho and Hanh2004); Andrade and Malta (Reference Andrade and Malta2006); Guidelli et al. (Reference Guidelli, Gomes Tavechio, Massato Takemoto and Pavanelli2006); Saraiva et al. (Reference Saraiva, Silva and Silva-Souza2006a); Saraiva et al. (Reference Saraiva, Rosim and Silva-Souza2006b); Araújo et al. (Reference Araújo, Gomes, Tavares-Dias, Andrade, Belém-Costa, Borges, Queiroz and Barbosa2009); Moreira et al. (Reference Moreira, Takemoto, Yamada, Ceschini and Pavanelli2009); Takemoto et al. (Reference Takemoto, Pavanelli, Lizama, Lacerda, Yamada, Moreira, Ceschini and Bellay2009); Azevedo et al. (Reference Azevedo, Abdallah and Luque2010); Moreira et al. (Reference Moreira, Yamada, Ceschini, Takemoto and Pavanelli2010); Kohn et al. (Reference Kohn, Moravec, Cohen, Canzi, Takemoto and Fernandes2011); Silva et al. (Reference Silva, Tavares-Dias and Fernandes2011); Vicentin et al. (Reference Vicentin, Vieira, Costa, Takemoto, Tavares and Paiva2011); Abdallah et al. (Reference Abdallah, Azevedo, Carvalho and Silva2012); Gaines et al. (Reference Gaines, Lozano, Viana, Monteiro and Araújo2012); Mesquita et al. (Reference Mesquita, Santos, Ceccarelli and Luque2012); Vicentin et al. (Reference Vicentin, Vieira, Tavares, Costa, Takemoto and Paiva2013); Gonçalves et al. (Reference Gonçalves, Oliveira, Santos and Tavres-Dias2014); Santos-Clapp and Brasil-Sato (Reference Santos-Clapp and Brasil-Sato2014); Tavares-Dias et al. (Reference Tavares-Dias, Sousa and Neves2014); Alcântara and Tavares-Dias (Reference Alcântara and Tavares-Dias2015); Dias et al. (Reference Dias, Neves, Marinho and Tavares-Dias2015a); Dias et al. (Reference Dias, Neves, Marinho, Pinheiro and Tavares-Dias2015b); Oliveira et al. (Reference Oliveira, Gonçalves, Neves and Tavares-Dias2015); Camargo et al. (Reference Camargo, Negrelli, Pedro, Azevedo, Silva and Abdallah2016); Hoshino et al. (Reference Hoshino, Neves and Tavres-Dias2016); Oliveira et al. (Reference Oliveira, Gonçalves and Tavares-Dias2016); Pedro et al. (Reference Pedro, Pellegrini, Azevedo and Abdallah2016); Ribeiro et al. (Reference RIBEIRO, UEDA, PAVANELLI and TAKEMOTO2016); Moreira et al. (Reference Moreira, Oliveira, Morey and Malta2017); Oliveira et al. (Reference Oliveira, Gonçalves, Ferreira, Pinheiro, Neves, Dias and Tavares-Dias2017); Santos and Tavares-Dias (Reference Santos and Tavares-Dias2017); Tavares-Dias (Reference Tavares-Dias2017); Tavares-Dias et al. (Reference Tavares-Dias, Gonçalves, Oliveira and Neves2017); Almeida-Berto et al. (Reference Almeida-Berto, Monteiro and Brasil-Sato2018); Fujimoto et al. (Reference Fujimoto, Couto, Sousa, Madi, Eiras and Martins2018); Leite et al. (Reference Leite, Pelegrini, Agostinho, Azevedo and Abdallah2018); Morey and Malta (Reference Morey and Malta2018a); Morey and Malta (Reference Morey and Malta2018b); Oliveira et al. (Reference Oliveira, Corrêa, Prestes, Neves, Brasiliense, Ferreira and Tavares-Dias2018); Pelegrini et al. (Reference Pelegrini, Januário, Azevedo and Abdallah2018); Pereira et al. (Reference Pereira, Mauad, Takemoto and Lima-Júnior2018); Baia et al. (Reference Baia, Santos, Silva E Silva, Sousa and Tavares-Dias2019); Ferreira et al. (Reference Ferreira, Passador and Tavares-Dias2019); Morais et al. (Reference Morais, Cárdenas and Malta2019); Negreiros et al. (Reference Negreiros, Pereira and Tavares-Dias2019); Oliveira et al. (Reference Oliveira, Corrêa and Tavares-Dias2019); Pereira et al. (Reference Pereira, Passador, Mendes-Júnior and Tavares-Dias2019); Acosta et al. (Reference Acosta, Smit and Silva2020); Ailán-Choke et al. (Reference Ailán-Choke, Tavares, Luque and Pereira2020); Carvalho et al. (Reference Carvalho, Ferreira, Araújo, Tavares-Dias, Matos and Videira2020); Corrêa et al. (Reference Corrêa, Takemoto, Ueta and Adriano2020); Gião et al. (Reference Gião, Pelegrini, Azevedo and Abdallah2020); Almeida et al. (Reference Almeida, Oliveira and Tavares-Dias2021); Borges et al. (Reference Borges, Oliveira and Tavares-Dias2021); Lima et al. (Reference Lima, Oliveira and Tavares-Dias2021); Negreiros et al. (Reference Negreiros, Neves and Tavares-Dias2021); Virgilio et al. (Reference Virgilio, Limas, Takemoto, Camargo and Meneguetti2021); Alexandre and Yamada (Reference Alexandre and Yamada2022); Brito-Júnior et al. (Reference Brito-Júnior, Oliveira and Tavres-Dias2022); Cárdenas et al. (Reference Cárdenas, Justo, Reyes and Cohen2022); Duarte et al. (Reference Duarte, Santos-Clapp and Brasil-Sato2022a); Duarte et al. (Reference Duarte, Santos-Clapp and Brasil-Sato2022b); Lima et al. (Reference Lima, Oliveira and Tavares-Dias2022); Santos-Clapp et al. (Reference Santos-Clapp, Duarte, Albuquerque and Brasil-Sato2022); Virgilio et al. (Reference Virgilio, Martins, Lima, Takemoto, Camargo and Meneguetti2022); Amaral et al. (Reference Amaral, Leão, Campos, Borges, Grano-Maldonado, Lino, Takemoto, Rocha and Damacena-Silva2023); De Sousa et al. (Reference De Sousa, Diniz, De Carvalho, Lopes and Yamada2023); Ferreira-Cordeiro et al. (Reference Ferreira-Cordeiro, Silva-Jtineant, Oliveira-Malta and Rapp-Py-Daniel2023); Falkenberg et al. (Reference Falkenberg, De Lima, Yamada, Ramos and Lacerda2024); Freitas et al. (Reference Freitas, Dantas-Filho, Gasparotto, Cama, García-Nuñez, Soares, Schons and Cavali2024); Lima and Tavares-Dias (Reference Lima and Tavares-Dias2023); Sousa et al. (Reference Sousa, Diniz, Yamada and Yamada2024); De Lima et al. (Reference De Lima, Mendonça-Filho, Lima, Honório, Falkenberg, Yamada, Lustosa-Costa, Ramos, Teixeira de Mello, Menezes, Windsor and Lacerda2025).

Unconfirmed hosts: Salminus brasiliensis (=Salminus maxillosus (Cuvier, 1816)) in Vicente and Pinto (Reference Vicente and Pinto1999); Brycon orthotaenia Günther, 1864, Charax gibbosus (Linnaeus, 1758), Leporinus agassizii Steindachner, 1876, Leporinus octofasciatus, Myloplus schomburgkii (Jardine, 1841) (=Myleus schomburgkii (Jardine, 1841)), Prochilodus lineatus, Pygocentrus sp., Salminus hilarii, Serrasalmus gouldingi Fink and Machado-Allison, 1992, Serrasalmus manueli (Fernández-Yépez and Ramírez, 1967) and Triportheus paranensis Günther, 1874 in Luque et al. (Reference Luque, Aguiar, Vieira, Gibson and Santos2011); Brycon melanopterus (Cope, 1872), Cichla ocellaris, Cichlasoma amazonarum Kullander, 1983, Geophagus brasiliensis, Hemibrycon surinamensis Géry, 1962, Psalidodon fasciatus (=Astyanax fasciatus) and Psalidodon paranae (Eigenmann, 1914) (=Astyanax paranae Eigenman, 1914) in Neves et al. (Reference Neves, Silva, Florentino and Tavares-Dias2020); Crenicichla jaguarensis Haseman 1911, Hoplias spp., Potamotrygon amandae and Piaractus mesopotamicus (Holmberg, 1887) in Lehun et al. (Reference Lehun, Hasuike, Silva, Ciccheto, Michelan, Rodrigues, Nicola, Lima, Correia and Takemoto2020); Brycon orthotaenia (=Brycon lundii Lütken, 1875) and Harttia duriventris Rapp Py-Daniel and Oliveira, 2001 in Santos Reis et al. (Reference Santos Reis, Santos, Nunes and Mugnai2021).

Spirocamallanus macaensis (Vicente and Santos, 1972)

Synonyms: Procamallanus macaensis Vicente and Santos, 1972; Procamallanus (Spirocamallanus) macaensis Vicente and Santos, 1972.

Hosts: Chaetodipterus faber (Broussonet, 1782), Dactylopterus volitans (Linnaeus, 1758), Menticirrhus americanus, Micropogonias undulatus (Linnaeus, 1766), Nebris microps Cuvier, 1830, Paralonchurus brasiliensis (Steindachner, 1875) (=Polyclemus brasiliensis Steindacner, 1875), Plagioscion auratus (Castelnau, 1855), Stellifer brasiliensis (Schultz, 1945), Thyrsitops lepidopoides (Cuvier, 1832), Urophycis brasiliensis, ‘cara-suja’ (local name).

Host environments: freshwater and marine.

Sites of infection: intestine.

Locality records: Southeast: Rio de Janeiro.

Biomes: Atlantic Forest.

Specimens deposited: type material CHIOC 30645a-e; vouchers CHIOC 30723a-d, 30794a-f, 30796a-c, 30797, 30805a-b, 30794a-b, 30795d-f, 32034a-f, 32035a-b, 33844-33846, 33849, 34107a-d, 38374–38376.

References: Vicente and Santos (Reference Vicente and Santos1972); Pinto and Noronha (Reference Pinto and Noronha1976); Santos et al. (Reference Santos, Cárdenas and Lent1999); Alves et al. (Reference Alves, Paraguassú and Luque2004); Cordeiro and Luque (Reference Cordeiro and Luque2005); Sardella et al. (Reference Sardella, Pereira and Luque2017).

Unconfirmed hosts: Urophycis sp. in Luque et al. (Reference Luque, Aguiar, Vieira, Gibson and Santos2011).

Remarks: Pinto and Noronha (Reference Pinto and Noronha1976) analysed the type material of Sp. macaensis deposited at CHIOC and evaluated the species’ validity. Sardella et al. (Reference Sardella, Pereira and Luque2017) redescribed Sp. macaensis and also reexamined the type material. Additionally, these authors examined some specimens of Spirocamallanus pereirai (Annereaux, 1946) reported in Brazil. They verified that part of this material corresponds to the species Sp. macaensis, while another part could not be identified to the species level due to poor preservation (deposit codes CHIOC 32034a-f, 32035a-b, 33844-33846, 33849, 34107a-d).

Spirocamallanus neocaballeroi Caballero-Deloya, 1977

Synonyms: Procamallanus (Spirocamallanus) neocaballeroi (Caballero-Deloya, 1977).

Hosts: Acestrorhynchus lacustris, Astyanax bimaculatus, Cichla monoculus, Leporinus piau, Moenkhausia costae, Poecilia vivipara Bloch and Schneider, 1801.

Host environments: freshwater.

Sites of infection: intestine.

Locality records: Northeast: Paraíba; Southeast: São Paulo.

Biomes: Caatinga and Cerrado.

Specimens deposited: CHIBB 6814.

References: Abdallah et al. (Reference Abdallah, Azevedo, Carvalho and Silva2012); De Lima et al. (Reference De Lima, Mendonça-Filho, Lima, Honório, Falkenberg, Yamada, Lustosa-Costa, Ramos, Teixeira de Mello, Menezes, Windsor and Lacerda2025); Sousa et al. (Reference Sousa, Falkenberg, Lima, Winkeler, Ramos, Lustosa-Costa, Menezes and Lacerda2025).

Unconfirmed hosts: Serrasalmus maculatus and Serrasalmus marginatus in Lehun et al. (Reference Lehun, Hasuike, Silva, Ciccheto, Michelan, Rodrigues, Nicola, Lima, Correia and Takemoto2020).

Spirocamallanus paraensis (Pinto and Noronha, 1976)

Synonyms: Procamallanus paraensis Pinto and Noronha, 1976; Procamallanus (Spirocamallanus) paraensis Pinto and Noronha, 1976.

Hosts: Hoplias malabaricus, ‘jeju’ (local name).

Host environments: freshwater.

Sites of infection: intestine.

Locality records: North: Pará.

Biomes: Amazon.

Specimens deposited: holotype CHIOC 31342b, allotype 31342d, paratypes 31342a,c.

References: Pinto and Noronha (Reference Pinto and Noronha1976); Corrêa et al. (Reference Corrêa, Tavares-Dias, Arana and Adriano2024).

Unconfirmed hosts: Erythrinus erythrinus in Luque et al. (Reference Luque, Aguiar, Vieira, Gibson and Santos2011) and Acestrorhynchus lacustris in Abdallah et al. (Reference Abdallah, Azevedo, Carvalho and Silva2012).

Remarks: Spirocamallanus paraensis was described based on material deposited in CHIOC.

Spirocamallanus pereirai (Annereaux, 1946)

Synonyms: Procamallanus pereirai Annereaux, 1946; Procamallanus (Spirocamallanus) pereirai (Annereaux, 1946).

Hosts: Atlantoraja castelnaui (Miranda Ribeiro, 1907) (=Raja castelnaui Miranda Ribeiro, 1907), Micropogonias furnieri (Desmarest, 1823), Mullus argentinae, Paralonchurus brasiliensis.

Host environments: marine.

Sites of infection: intestine, spiral valve.

Locality records: Northeast: Bahia; South: Rio Grande do Sul; Southeast: Minas Gerais, Rio de Janeiro.

Biomes: Atlantic Forest and Pampa.

Specimens deposited: vouchers CHIOC 34264, 34265a-c, 34266, 35105.

References: Pinto et al. (Reference Pinto, Vicente and Noronha1984); Knoff et al. (Reference Knoff, São Clemente, Pinto and Gomes2001); Ribeiro et al . (2002); Luque et al. (Reference Luque, Alves and Ribeiro2003); Luque et al. (Reference Luque, Cordeiro and Oliva2010); Simões et al. (Reference Simões, Cardoso, Pereira, Paschoal and Luque2025).

Unconfirmed specimens deposited: deposit codes CHIOC 32034a-f and 32035a-b in Pinto et al. (Reference Pinto, Vicente and Noronha1984).

Remarks: Sardella et al. (Reference Sardella, Pereira and Luque2017) analysed materials deposited in CHIOC identified as Sp. pereirai, but they reallocated these specimens as Sp. macaensis or Spirocamallanus sp. The present survey for Sp. pereirai in Brazil refers to specimens attributed to Sp. pereirai that were not analysed by Sardella et al. (Reference Sardella, Pereira and Luque2017).

The study by Knoff et al. (Reference Knoff, São Clemente, Pinto and Gomes2001) indicates that the material is only from Rio Grande do Sul (South), but, checking the CHIOC codes provided by the authors, part of the material was also collected in Minas Gerais (Southeast) (according to the data recorded in CHIOC). Additionally, the deposit codes provided by Pinto et al. (Reference Pinto, Vicente and Noronha1984) are not included in the CHIOC online catalogue.

Spirocamallanus pimelodus (Pinto, Fabio, Noronha and Rolas, 1974)

Synonyms: Procamallanus pimelodus Pinto, Fabio, Noronha and Rolas, 1974; Procamallanus (Spirocamallanus) pimelodus Pinto, Fabio, Noronha and Rolas, 1974; Procamallanus (Spirocamallanus) intermedius Pinto, Fabio, Noronha and Rolas, 1974; Procamallanus intermedius Pinto, Fabio, Noronha and Rolas, 1974; Spirocamallanus intermedius (Pinto, Fabio, Noronha and Rolas, 1974).

Hosts: Bujurquina cordemadi Kullander, 1986, Heros severus, Iheringichthys labrosus (Lütken, 1874), Nemadoras humeralis, Pimelodella lateristriga, Pimelodus blochii, Pimelodus maculatus, Pimelodus ortmanni, Pimelodus pohli, Serrasalmus maculatus, Solea senegalensis Kaup, 1858, Synodontis clarias (=Pimelodus clarias).

Host environments: freshwater.

Sites of infection: intestine.

Locality records: Midwest: Mato Grosso; North: Acre; South: Paraná; Southeast: Minas Gerais, São Paulo.

Biomes: Amazon, Atlantic Forest and Cerrado.

Specimens deposited: holotype CHIOC 30993, allotype 30999, paratypes 30989a-b, 30990, 30991, 30992a-b, 30993b-i, 30994, 30995a-b, 30996, 30997a-b, 30998a-c, 30999b-f, 31000a-c, 31001, 31002a-b, 31003a-b, 31004a-c, 31005a-c, 31006a-d, 31007, 31008a-b, 31009a-c, 31010, 31011; voucher CHIOC 31022a, 31023a, 31022 b-h, 31023 b-c, 32024, 31025a-b (type series of Spirocamallanus intermedius); CHIOC 35918.

References: Kohn and Fernandes (Reference Kohn and Fernandes1987); Kohn et al. (Reference Kohn, Fernandes, Pipolo and Godoy1988); Pinto et al. (Reference Pinto, Fabio, Noronha and Rolas1974); Moravec et al. (Reference Moravec, Kohn and Fernandes1993); Moreira et al. (Reference Moreira, Ito, Takemoto and Pavanelli2005); Takemoto et al. (Reference Takemoto, Pavanelli, Lizama, Lacerda, Yamada, Moreira, Ceschini and Bellay2009); Kohn et al. (Reference Kohn, Moravec, Cohen, Canzi, Takemoto and Fernandes2011); Sabas and Brasil-Sato (Reference Sabas and Brasil-Sato2014); Negreiros et al. (Reference Negreiros, Pereira, Tavares-Dias and Tavares2018); Cavalcante et al. (Reference Cavalcante, Silva, Pereira, Gentile and Santos2020); Virgilio et al. (Reference Virgilio, Martins, Lima, Takemoto, Camargo and Meneguetti2022); Negreiros et al. (Reference Negreiros, Couto and Tavares-Dias2024).

Unconfirmed hosts: Pimelodus sp. in Luque et al. (Reference Luque, Aguiar, Vieira, Gibson and Santos2011).

Remarks: Pinto et al. (Reference Pinto, Fabio, Noronha and Rolas1974) described the species Sp. pimelodus and Sp. intermedius Pinto, Fabio, Noronha and Rolas, 1974 in the same study, both parasitizing the intestine of the same host species, Synodontis clarias (=Pimelodus clarias), and Moravec et al. (Reference Moravec, Kohn and Fernandes1993) synonymized them, considering that the differences highlighted between the species described by Pinto et al. (Reference Pinto, Fabio, Noronha and Rolas1974) are not sufficient to differentiate the 2 species.

Analysing the descriptions of both species, the main characteristic to differentiate Sp. intermedius was the morphology of the larger spicule, which is bifurcated at its distal end and divided into zones. In contrast, the spicule of Sp. pimelodus has a pointed tip, and this morphological difference should be sufficient to separate the 2 species.