Although the normative model of rationality discussed in Chapter 1 is central to microeconomics, microeconomics is a positive theory describing, predicting, and explaining actual choices and their consequences. This chapter examines the microeconomic theory of consumer choice. Along the way we shall see an example of an economic model and, in reflecting on the theory of consumer choice and the explanation of demand, many questions will arise concerning the structure of economic theory and whether the propositions of economic theory are in accord with the evidence. The material here should be familiar to economists.

2.1 Market Demand for Consumption Goods

One central generalization of economics is the law of demand, which can be stated as: higher prices diminish demand for commodities and services, while lower prices increase demand. For example, an increase in the price of gasoline leads consumers to purchase less gas.

There are several things to note about the law of demand:

1. It is not mysterious or deeply theoretical. It is part of the experience of retailers who hold sales to eliminate excess inventory.

2. It is a generalization about markets, not about individuals.

3. The law of demand cannot be stated simply as: price and quantity demanded are inversely correlated. For example, in August, when many families take car trips, both the price of gasoline and the amount purchased may be larger than in February. Economists distinguish between the effects of a change in the price of gasoline, which is a movement “along a demand curve” and the effects of other factors, such as whether families go on vacation, which imply a shift in the demand curve. The law of demand is a causal claim that price increases cause decreases in quantity demanded, and price decreases cause increases in quantity demanded. Unlike inverse correlation, which is a symmetric relation, there is an asymmetric causal relation here.

How is one to make a generalization such as the law of demand more precise and serviceable? One might start by attempting to list the major factors that influence market demand:Footnote 1

Demand for any commodity or service causally depends on its price:

;

;  .Footnote 2

.Footnote 2Demand depends on the price of substitutes. If

and

and  are substitutes then

are substitutes then  and

and  . For example, demand for tea causally depends not only on the price of tea but also on the price of coffee. Groups of commodities or services such as coffee and tea that meet similar needs or satisfy similar wants are called “substitutes” by economists.

. For example, demand for tea causally depends not only on the price of tea but also on the price of coffee. Groups of commodities or services such as coffee and tea that meet similar needs or satisfy similar wants are called “substitutes” by economists.Demand causally depends on the price of complements. If

and

and  are complements, then

are complements, then  and

and  . For example, people want jam with bread and DVDs with their DVD players. Groups of commodities or services that are consumed together are called “complements” by economists.

. For example, people want jam with bread and DVDs with their DVD players. Groups of commodities or services that are consumed together are called “complements” by economists.Demand causally depends on income and wealth. If

is a normal good, then income

is a normal good, then income  and income

and income  . An increase in the average income and wealth of buyers causes people in societies such as ours typically to demand more of “normal” goods and less of “inferior” goods.Footnote 3

. An increase in the average income and wealth of buyers causes people in societies such as ours typically to demand more of “normal” goods and less of “inferior” goods.Footnote 3Demand causally depends on tastes or fads. When I was a child in the suburbs of Chicago, yogurt was an unusual specialty item and kiwifruit were unheard of. Demand for these commodities increased because people came to want them.

These additional generalizations provide a more detailed grasp of market behavior than does the law of demand by itself. However, without further generalizations about the strength and stability of these different causal factors, economists have no general way to predict even the direction of a change in demand in response to price changes. Furthermore, even if economists were able to use these generalizations to predict changes in prices and quantities purchased, these generalizations provide little theoretical depth. If economists stopped here, they would have no explanation for why these generalizations obtain, and their explanations of market phenomena would be superficial.

Empirical research can flesh out these generalizations. With sufficient data, it is possible to estimate the magnitude of the change in demand for ![]() with respect to changes in the price of

with respect to changes in the price of ![]() , ceteris paribus or the changes in demand ceteris paribus, in response to changes in the prices of substitutes or complements. Large firms devote substantial resources to the empirical study of market behavior, and there is a well-established body of econometric techniques that are employed to estimate the responsiveness of demand (and supply) to various causal influences.

, ceteris paribus or the changes in demand ceteris paribus, in response to changes in the prices of substitutes or complements. Large firms devote substantial resources to the empirical study of market behavior, and there is a well-established body of econometric techniques that are employed to estimate the responsiveness of demand (and supply) to various causal influences.

Market generalizations, rendered quantitative by econometric inferences from statistical data and by empirical research are precarious. Fads are quirky. The introduction of new products can disrupt settled patterns of consumption. Although it is possible that incomes, tastes, and the prices of complements and substitutes happen not to change so that the change in demand ![]() ceteris paribus with a change in the price of

ceteris paribus with a change in the price of ![]() is the actual change in demand, it is more often the case that ceteris is not paribus – that is, other things apart from the particular causal variable one is interested in also change. So, in addition to determining the causal relations between individual causal variables and

is the actual change in demand, it is more often the case that ceteris is not paribus – that is, other things apart from the particular causal variable one is interested in also change. So, in addition to determining the causal relations between individual causal variables and ![]() , economists need to know how to combine the effects of multiple causes.

, economists need to know how to combine the effects of multiple causes.

Moreover, no matter how useful generalizations relating ![]() to various causal factors may be to firms who seek advice concerning how to price or package their products, these generalizations by themselves must be disappointing to economic theorists who aspire to imitate the great achievements of the natural sciences. For, apart from statistical techniques and empirical research methods, there is little theory here.

to various causal factors may be to firms who seek advice concerning how to price or package their products, these generalizations by themselves must be disappointing to economic theorists who aspire to imitate the great achievements of the natural sciences. For, apart from statistical techniques and empirical research methods, there is little theory here.

Those economists interested in theory – and not all economists are or should be interested in theory – have attempted to put demand and consumer choice on a deeper and more secure theoretical footing. Starting with the basic model of rational choice, they have attempted to find further generalizations concerning the choice behavior of individuals that explain, systematize, and unify causal generalizations concerning market behavior. Just as Newton’s theory of motion and gravitation accounts for (and corrects) Galileo’s law of falling bodies and Kepler’s laws of planetary motion, so a deeper theory of the economic behavior of individuals might account for and possibly correct generalizations concerning market behavior. This strategic choice is neither inevitable nor guaranteed to succeed. More superficial and less unified models seem to be lesser scientific achievements than a deeper and more unified model of consumer choices, but the deeper account may not be attainable or more useful.

2.2 The Theory of Consumer Choice

Consumer choice theory is supposed to explain the causal generalizations discussed in Section 2.1 concerning market demand. It is made up of the following three “behavioral postulates” or “laws” (§A.4):

1. Consumers are rational – that is, they have complete, transitive, reflexive, and continuous preferences and do not prefer any known (affordable) option to the one they choose.

2. Consumers are acquisitive – that is:

a. the objects of every individual

’s preferences are bundles of commodities consumed by

’s preferences are bundles of commodities consumed by  ,

,b. there are no interdependencies between the preferences of different individuals,

c. up to some point of satiation (that is typically unattained), individuals prefer larger commodity bundles to smaller (bundle

is larger than bundle

is larger than bundle  if

if  contains at least as much of every commodity or service as does

contains at least as much of every commodity or service as does  and more of some commodity or service), and

and more of some commodity or service), andd. although a consumer may be acquisitive because of some ultimate altruistic aim (of no interest to consumer choice theory), the proximate goals of acquisitive consumers are self-interested.

3. The preferences of consumers for commodities and services show diminishing marginal rates of substitution – DMRS. For all individuals

and all commodities or services

and all commodities or services  and

and  ,

,  is willing to exchange more of

is willing to exchange more of  for a unit of

for a unit of  as the amount of

as the amount of  has increases relative to the amount of

has increases relative to the amount of  has.Footnote 4

has.Footnote 4

In Chapter 1, I discussed the definition or model of rationality that is used here. An individual ![]() is rational if and only if

is rational if and only if ![]() ’s preferences are complete, transitive, reflexive, and continuous, and

’s preferences are complete, transitive, reflexive, and continuous, and ![]() never prefers any option

never prefers any option ![]() knows to be available to the option

knows to be available to the option ![]() chooses. In the context of consumer choice theory, an available option is an affordable commodity bundle. Whether taken as normative or positive, utility theory has a much wider scope than economics. The second “law,” which asserts that consumers are acquisitive, brings utility theory to bear on economic behavior.Footnote 5 This generalization is a cluster of claims. One might call it “nonsatiation,” but doing so overemphasizes one element in the cluster. One might call it “self-interest,” but doing so would not highlight the limitation of preferences to commodity bundles. One might speak of “greed,” but that would sound pejorative. To say that it regards consumers as acquisitive seems the best compromise, although the label may misleadingly suggest a preference for money rather than what money can buy.

chooses. In the context of consumer choice theory, an available option is an affordable commodity bundle. Whether taken as normative or positive, utility theory has a much wider scope than economics. The second “law,” which asserts that consumers are acquisitive, brings utility theory to bear on economic behavior.Footnote 5 This generalization is a cluster of claims. One might call it “nonsatiation,” but doing so overemphasizes one element in the cluster. One might call it “self-interest,” but doing so would not highlight the limitation of preferences to commodity bundles. One might speak of “greed,” but that would sound pejorative. To say that it regards consumers as acquisitive seems the best compromise, although the label may misleadingly suggest a preference for money rather than what money can buy.

To say that consumers are acquisitive is to say that, unless satiated, they want more of all commodities and services. As economists recognize, this claim is a caricature of human behavior. Like the other generalizations, it might be defended as a reasonable first approximation; as a harmless distortion of reality that is required for the construction of a manageable theory. One might argue that it captures a causal “tendency” that is central to economic behavior. Alternatively, one might argue that, given the presence of markets, to regard people as acquisitive is not such a gross exaggeration after all. Since one can always sell one’s fifth computer and donate the money to a favorite charity, even altruists might prefer a commodity bundle containing five computers to one containing only four. The objection that selling a used computer is not costless in terms of time and hassle misses the mark, because, to the extent that it is correct, it is not the case that the five-computer commodity bundle differs from the four-computer bundle only in the number of computers. On the contrary, the five-computer bundle arguably possesses less leisure.Footnote 6

If individuals are acquisitive, then their immediate objectives are self-interested, for their preferences are over bundles of goods and services, and by denying any interdependence of preferences economists rule out commodities or services such as food for starving Ethiopians, which might be on sale from Oxfam. Acquisitiveness demands that the satisfaction of the preferences of others not be included, even implicitly, among the arguments of my utility function.Footnote 7 Acquisitiveness identifies options with commodity bundles and implies that choices are based on wanting more of everything. Whereas utility theory is perfectly consistent with altruism, the claim that people are acquisitive rules out immediately altruistic objectives. It is the assumption that consumers are acquisitive that confines attention not only to “rational man” but to “economic man,” who is motivated by the pursuit of what money can buy. The claim that people are acquisitive rules out both direct concern with the plight of others and envious concern with the successes of others. Although overly cynical economists and students of economics may believe that people are exclusively acquisitive, a more charitable interpretation attributes to economists the view that, although false, acquisitiveness is a useful exaggeration with respect to market behavior.

The “law” of DMRS implies that the amount that a consumer such as Penelope will pay for a portion of some good or service ![]() diminishes as the amount of

diminishes as the amount of ![]() that Penelope possesses increases. She is willing to pay less for her second bag of French fries than for her first. It is difficult to state DMRS in its full generality without the help of mathematics. A helpful way to grasp what it says is to use some old-fashioned language. Suppose that rather than merely indicating preferences, utility functions measure some quantity, such as pleasure, and that, as is the case in expected utility theory, utilities have cardinal, not merely ordinal, significance – that is, differences between the utilities of different alternatives are not arbitrary.

that Penelope possesses increases. She is willing to pay less for her second bag of French fries than for her first. It is difficult to state DMRS in its full generality without the help of mathematics. A helpful way to grasp what it says is to use some old-fashioned language. Suppose that rather than merely indicating preferences, utility functions measure some quantity, such as pleasure, and that, as is the case in expected utility theory, utilities have cardinal, not merely ordinal, significance – that is, differences between the utilities of different alternatives are not arbitrary.

Employing a cardinal notion of utility, nineteenth-century economists formulated a law of diminishing marginal utility. This law, which was independently discovered by several economists, was one cornerstone of the so-called neoclassical or marginalist revolution in economics in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. If commodity bundle ![]() differs from bundle

differs from bundle ![]() only in containing more of some commodity

only in containing more of some commodity ![]() , then acquisitive consumers will prefer

, then acquisitive consumers will prefer ![]() to

to ![]() . The law of diminishing marginal utility offers the further generalization that the size of this (positive) increment in the utility of

. The law of diminishing marginal utility offers the further generalization that the size of this (positive) increment in the utility of ![]() as compared to

as compared to ![]() is a decreasing function of the amount of

is a decreasing function of the amount of ![]() already in

already in ![]() . As Penelope keeps eating French fries, the amount by which an additional French fry increases her total pleasure becomes smaller and smaller.

. As Penelope keeps eating French fries, the amount by which an additional French fry increases her total pleasure becomes smaller and smaller.

Apart from qualms about identifying utility with some substantive good such as pleasure, the law of diminishing marginal utility seems plausible. There are grounds to deny that it is universally true (see Karelis Reference Karelis1986), but it is plausible in many contexts. It neatly explains the paradoxical fact that useful but plentiful goods, such as water, are often cheaper than relatively useless but scarce goods, such as diamonds – a fact that bothered eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century economists. But if, as in contemporary economics, utility functions are no more than a means of representing preference rankings, differences in utilities are arbitrary, and one cannot sensibly speak of diminishing marginal utility.

The law of DMRS is Edgeworth’s (Reference Edgeworth1881) and Pareto’s (Reference Pareto1909, chapters 3 and 4) trick for capturing the implications of diminishing marginal utility for consumer choice without commitment to cardinal utilities. The idea was rediscovered and popularized by J. R. Hicks and R. G. Allen (Reference Hicks and Allen1934). The essence is that an individual is willing to trade away more of ![]() to get a unit of

to get a unit of ![]() when he or she has little of

when he or she has little of ![]() than when he or she has a great deal of

than when he or she has a great deal of ![]() . Instead of looking at the utility increment provided by an additional unit of

. Instead of looking at the utility increment provided by an additional unit of ![]() as a function of the amount of

as a function of the amount of ![]() , economists can look at the terms of exchange between

, economists can look at the terms of exchange between ![]() and other commodities. The notion of marginal utility may still be lurking in the background as an explanation for DMRS, but all that consumer choice theory needs are ordinal utilities, acquisitiveness, and diminishing marginal rates of substitution.

and other commodities. The notion of marginal utility may still be lurking in the background as an explanation for DMRS, but all that consumer choice theory needs are ordinal utilities, acquisitiveness, and diminishing marginal rates of substitution.

One no more understands consumer choice theory by learning its constituent generalizations than one understands quantum theory by learning the Schrödinger equation. One needs to see how rationality, acquisitiveness, and DMRS are used together and what simplifications and mathematical techniques are required to bring them to bear on economic phenomena. When we see how the theory of consumer choice accounts for market demand, we shall have a better sense of the theory.

Regardless of its success in accounting for market phenomena, the theory of consumer choice is a troubling theory, for it is hard to regard its basic claims as “laws” without the scare quotes. This problem lies at the heart of most methodological discussion concerning economics and is discussed in Part II.

In treating theories as sets of “laws” or “lawlike” statements, I am assuming the answer to the philosophical question, “what is a scientific theory?” (§A.4). This view of scientific theories is defended Chapter 6.

2.3 Market Demand and Individual Demand Functions

Economists explain market demand in terms of individual demand. With preferences, prices, and budgets already fixed, consumers possess, as it were, a shopping list for commodities and services upon which they can spend their budgets. The market demand for each commodity or service ![]() is the sum of all the individual demands – that is, the sum of the quantities of

is the sum of all the individual demands – that is, the sum of the quantities of ![]() ,

, ![]() , etc. that are on the shopping lists. The market demand function (for

, etc. that are on the shopping lists. The market demand function (for ![]() ) is a mapping from prices, incomes, and preferences to amounts of

) is a mapping from prices, incomes, and preferences to amounts of ![]() demanded. As in many elementary treatments, the discussion here oversimplifies and takes market demand functions to be the sum of individual demand functions (for a careful treatment, see Friedman Reference Friedman1962).

demanded. As in many elementary treatments, the discussion here oversimplifies and takes market demand functions to be the sum of individual demand functions (for a careful treatment, see Friedman Reference Friedman1962).

A more substantive step in the explanation of market demand is the derivation of individual demand functions from consumer choice theory and from further statements concerning the institutional and epistemic (belief or knowledge) circumstances in which consumers choose. An individual demand function for a commodity or service ![]() states how much of

states how much of ![]() (as a flow of

(as a flow of ![]() per unit time) is demanded by an individual

per unit time) is demanded by an individual ![]() as a function of causal variables, some of which may be left implicit within a ceteris paribus condition. For example, when economists treat the quantity of

as a function of causal variables, some of which may be left implicit within a ceteris paribus condition. For example, when economists treat the quantity of ![]() that

that ![]() demands as a function only of the price of

demands as a function only of the price of ![]() (ceteris paribus), they are not denying that

(ceteris paribus), they are not denying that ![]() ’s demand for

’s demand for ![]() also depends on income, tastes, and other prices. When these other causal determinants of

also depends on income, tastes, and other prices. When these other causal determinants of ![]() ’s demand for

’s demand for ![]() change, the demand curve – that is, the functional relationship between the price of

change, the demand curve – that is, the functional relationship between the price of ![]()

![]() and the quantity of

and the quantity of ![]() demanded by

demanded by ![]() will shift. Suppose for concreteness that

will shift. Suppose for concreteness that ![]() is coffee and that there is a change in both its price and in the price of a substitute for coffee such as tea. The change in demand for coffee with a change in the price of coffee will differ from what it would have been had the price of tea not changed. If in a particular application such changes are small or rare, it is handy to consider explicitly only the causal dependence of

is coffee and that there is a change in both its price and in the price of a substitute for coffee such as tea. The change in demand for coffee with a change in the price of coffee will differ from what it would have been had the price of tea not changed. If in a particular application such changes are small or rare, it is handy to consider explicitly only the causal dependence of ![]() on

on ![]() and to hide the impact of the other causal influences in a ceteris paribus clause.

and to hide the impact of the other causal influences in a ceteris paribus clause.

The simplest models of demand, which suppose that individuals can choose among quantities of only two commodities, have special limitations and serve as pedagogical devices much more than explanatory or predictive tools. I focus on them here, because they permit a graphical treatment and are easy to understand. They also illustrate central features of economic modeling and how fundamental theory is employed to derive and to explain useful but more superficial economic generalizations.

2.4 The Model of a Two-Commodity Consumption System

To derive features of individual demand functions from the generalizations of consumer choice theory, economists employ models of consumer choice. I call the simplest of these models a “two-commodity consumption system.” This is my terminology. You will not find it in any economics textbooks.

A two-commodity consumption system is supposed to model the behavior of some individual agent, ![]() , faced with a choice between bundles of only two commodities

, faced with a choice between bundles of only two commodities ![]() and

and ![]() in the context of a market economy, where prices are already posted and

in the context of a market economy, where prices are already posted and ![]() ’s income is already determined. Obviously, consumption possibilities include many more than two commodities or services, but one might treat all commodities except one as a single composite commodity. Let us suppose that Alice chooses a consumption bundle consisting of coffee (

’s income is already determined. Obviously, consumption possibilities include many more than two commodities or services, but one might treat all commodities except one as a single composite commodity. Let us suppose that Alice chooses a consumption bundle consisting of coffee (![]() ) and “everything-else-Alice-consumes” (

) and “everything-else-Alice-consumes” (![]() ). One then formulates the model of a two-commodity consumption system as follows.

). One then formulates the model of a two-commodity consumption system as follows.

A quadruple ![]() is a two-commodity consumption system if and only if:

is a two-commodity consumption system if and only if:

1.

is an agent,

is an agent,  and

and  are kinds of commodities or services, and

are kinds of commodities or services, and  is the agent’s income.

is the agent’s income.2.

faces a choice over a convex set of bundles of commodities

faces a choice over a convex set of bundles of commodities  , where

, where  and

and  are non-negative real numbers representing quantities of

are non-negative real numbers representing quantities of  and

and  respectively.Footnote 8

respectively.Footnote 83.

’s income,

’s income,  , is a fixed amount known to

, is a fixed amount known to  , and it is entirely spent on the purchase of a bundle

, and it is entirely spent on the purchase of a bundle  .

.4. The prices of

and

and  ,

,  and

and  , are fixed and known to

, are fixed and known to  .

.5.

’s utility function is a strictly quasi-concave, increasing, and differentiable function of

’s utility function is a strictly quasi-concave, increasing, and differentiable function of  and

and  (or, alternatively,

(or, alternatively,  ’s indifference curves are continuous and convex to the origin).

’s indifference curves are continuous and convex to the origin).6.

chooses the bundle

chooses the bundle  that maximizes

that maximizes  ’s utility function subject to the constraint that

’s utility function subject to the constraint that  (or the bundle

(or the bundle  is on the highest attainable indifference curve).Footnote 9

is on the highest attainable indifference curve).Footnote 9

These six assumptions fall into three classes: (a) simplified specifications of the institutional and epistemic setting – for example, fixed and known prices and income; (b) restatements or specifications of the “laws” of consumer choice theory – for example, maximization of utility functions that show acquisitiveness and DMRS; and (c) further simplifications whose role is to make the analysis easy and determinate – for example, only two infinitely divisible commodities. The model is not an uninterpreted mathematical structure. It defines a quadruple of agent, commodities, and income.

Here are some further details concerning the three groups of assumptions that define a two-commodity consumption system:

(a) Institutional and epistemic assumptions. The highly simplified specification of the institutional and epistemic setting in the two-commodity consumption system is common in many economic models. By attributing perfect knowledge to individuals, economists spare themselves any inquiry into the beliefs of agents (§1.2). The assumption that the agent is a “price taker” – that is, that the agent cannot intentionally influence prices – is common and part of the definition of what economists call “perfect competition.” Introducing the possibility of bargaining would make the outcome depend on bargaining power and skill, which would complicate the model and reduce its determinacy.

(b) Specifications of the “laws.” The generalizations concerning preference and choice that make up the theory of consumer choice appear in mathematical dress. Assumption 6 of the model says that

chooses a commodity bundle that maximizes

chooses a commodity bundle that maximizes  ’s utility, subject to the constraint that the value of

’s utility, subject to the constraint that the value of  ’s consumption must not exceed

’s consumption must not exceed  ’s income. This is just a restatement of what I called the choice determinacy axiom. It means nothing more than that, subject to the budget constraint,

’s income. This is just a restatement of what I called the choice determinacy axiom. It means nothing more than that, subject to the budget constraint,  chooses what

chooses what  most prefers.

most prefers.The continuous utility function mentioned in assumptions 5 and 6 is an ordinal utility function and is definable only if

’s preferences are complete, transitive, reflexive, and continuous. Stipulating that

’s preferences are complete, transitive, reflexive, and continuous. Stipulating that  ’s utility is an increasing function of both

’s utility is an increasing function of both  and

and  is asserting that

is asserting that  is acquisitive. Demanding that the utility function be differentiable is merely a mathematical convenience.Footnote 10 Finally, to stipulate that the utility function must be strictly quasi-concave restates the law of DMRS. Suppose that for any bundles of the two commodities

is acquisitive. Demanding that the utility function be differentiable is merely a mathematical convenience.Footnote 10 Finally, to stipulate that the utility function must be strictly quasi-concave restates the law of DMRS. Suppose that for any bundles of the two commodities  and

and  ,

,  . Then the function

. Then the function  is strictly quasi-concave if and only if for all

is strictly quasi-concave if and only if for all  strictly between

strictly between  and

and  (Malinvaud Reference Malinvaud1972, p. 26). The alternative formulation of assumption 5 in terms of indifference curves is discussed in the next section.

(Malinvaud Reference Malinvaud1972, p. 26). The alternative formulation of assumption 5 in terms of indifference curves is discussed in the next section.(c) Further simplifications in the model. Although the institutional and epistemic specifications and the restatements of the “laws” of the theory of consumer choice are problematic, what seems strange or perhaps even bizarre (until one becomes accustomed to the habits of economists) are the extreme simplifications – a convex consumption set containing only two commodities and all income spent. (A set is convex if a line between any two points in the set is entirely contained in the set. So, among other things, the convexity of the set of commodity bundles implies that commodities are infinitely divisible.)

Despite the extreme simplifications, models such as the two-commodity consumption system are not silly. Some of the simplifications are avoidable and one can investigate whether those that are not avoidable are likely to lead to significant error. At the cost of mathematical complexities and some indeterminacies, one can analyze consumer choice among indivisible commodities. Taking income as fixed separates decisions to consume from decisions to devote resources to increasing income or future consumption. Depending on which questions the model is intended to answer, economists may regard this separation as a helpful first approximation. When at the supermarket, people typically take their incomes as given.

2.5 Deriving Individual Demand

In principle, it is possible to derive a fully specified demand function for a particular individual from information about the individual’s preferences and incomes and the price and availability of commodities and services. However, economists never know enough to carry out such a derivation. Instead, they show how such a derivation could be carried out, and they show that axioms concerning preferences specified by consumer choice theory imply the generalizations concerning market demand with which this chapter began.

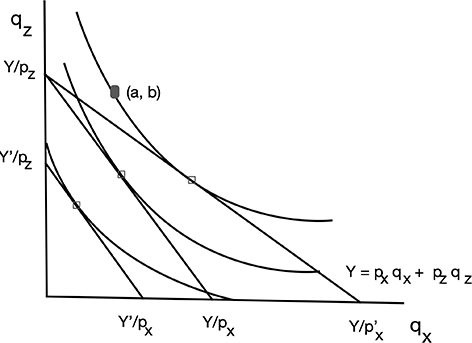

Since the commodity bundles among which ![]() chooses contain only two infinitely divisible commodities, the whole set of consumption possibilities may be represented by the portion of the

chooses contain only two infinitely divisible commodities, the whole set of consumption possibilities may be represented by the portion of the ![]() plane bounded below and to the left by the lines

plane bounded below and to the left by the lines ![]() and

and ![]() (see Figure 2.1). Each point

(see Figure 2.1). Each point ![]() in this quadrant represents a commodity bundle consisting of

in this quadrant represents a commodity bundle consisting of ![]() units of commodity

units of commodity ![]() and

and ![]() units of commodity

units of commodity ![]() . This is an instance of what economists call a “commodity space,” and

. This is an instance of what economists call a “commodity space,” and ![]() utility function assigns a utility (ranking) to each point. If commodity bundle

utility function assigns a utility (ranking) to each point. If commodity bundle ![]() is northeast of

is northeast of ![]() (above and to the right of it), then because

(above and to the right of it), then because ![]() is acquisitive,

is acquisitive, ![]() prefers

prefers ![]() to

to ![]() .

.

Figure 2.1 Indifference curves.

One can represent ![]() ’s budget constraint by the line,

’s budget constraint by the line, ![]() It is a straight line with the slope

It is a straight line with the slope ![]() that intersects the

that intersects the ![]() axis at

axis at ![]() and the

and the ![]() axis at

axis at ![]() .

. ![]() wants to move as far northeast as possible but cannot spend more than

wants to move as far northeast as possible but cannot spend more than ![]() , which means that

, which means that ![]() ’s consumption lies somewhere along the budget line.

’s consumption lies somewhere along the budget line.

![]() ’s preferences, in the form of

’s preferences, in the form of ![]() ’s “indifference curves,” determine where

’s “indifference curves,” determine where ![]() ’s consumption lies along the budget line. A point in the commodity space

’s consumption lies along the budget line. A point in the commodity space ![]() lies on the indifference curve through the point

lies on the indifference curve through the point ![]() if and only if

if and only if ![]() is indifferent between

is indifferent between ![]() and

and ![]() . Since commodities are infinitely divisible and

. Since commodities are infinitely divisible and ![]() ’s utility function is continuous,

’s utility function is continuous, ![]() ’s indifference curves will be continuous. If

’s indifference curves will be continuous. If ![]() is northeast (or southwest) of

is northeast (or southwest) of ![]() , then

, then ![]() cannot lie on the indifference curve passing through

cannot lie on the indifference curve passing through ![]() , and, given the transitivity of indifference, the indifference curve including

, and, given the transitivity of indifference, the indifference curve including ![]() cannot intersect the indifference curve including

cannot intersect the indifference curve including ![]() .

.

Because ![]() ’s utility function depends on two variables,

’s utility function depends on two variables, ![]() and

and ![]() , its graph would require three dimensions, but, since the values of the utilities, apart from the ordering, do not matter, one loses nothing by representing

, its graph would require three dimensions, but, since the values of the utilities, apart from the ordering, do not matter, one loses nothing by representing ![]() ’s preferences by indifference curves, which can be drawn in two dimensions. Instead of relying on the strict quasi-concavity of the utility function to draw inferences concerning

’s preferences by indifference curves, which can be drawn in two dimensions. Instead of relying on the strict quasi-concavity of the utility function to draw inferences concerning ![]() ’s consumption choice, economists can make use of the closely related claim that

’s consumption choice, economists can make use of the closely related claim that ![]() ’s indifference curves are convex to the origin, that is, that they have the shape represented in Figure 2.1. The claim that

’s indifference curves are convex to the origin, that is, that they have the shape represented in Figure 2.1. The claim that ![]() ’s indifference curves are everywhere convex to the origin is a perspicuous mathematical restatement of the law of DMRS. The absolute value of the marginal rate of substitution, given that

’s indifference curves are everywhere convex to the origin is a perspicuous mathematical restatement of the law of DMRS. The absolute value of the marginal rate of substitution, given that ![]() possesses commodity bundle

possesses commodity bundle ![]() , is the slope of the indifference curve passing through

, is the slope of the indifference curve passing through ![]() at point

at point ![]() . As

. As ![]() relative to

relative to ![]() increases, the magnitude of the slope of the indifference curve increases ever more slowly. If

increases, the magnitude of the slope of the indifference curve increases ever more slowly. If ![]() is small, a small amount of

is small, a small amount of ![]() sacrificed for a large amount of

sacrificed for a large amount of ![]() keeps

keeps ![]() on the same indifference curve.

on the same indifference curve.

![]() does what he or she most prefers if and only if

does what he or she most prefers if and only if ![]() chooses a bundle on the highest indifference curve that intersects the budget line. That indifference curve will be tangent to the budget line, except in the case of a so-called corner solution, where the highest indifference curve intersects the budget line at one of the axes.

chooses a bundle on the highest indifference curve that intersects the budget line. That indifference curve will be tangent to the budget line, except in the case of a so-called corner solution, where the highest indifference curve intersects the budget line at one of the axes.

Suppose ![]() were coffee and

were coffee and ![]() were “

were “![]() ” (the composite commodity consisting of everything else that

” (the composite commodity consisting of everything else that ![]() consumes). Suppose also that

consumes). Suppose also that ![]() is some particular person, Alice. Economists could predict exactly how much coffee Alice buys if they knew Alice’s income, the price of coffee, some index price for

is some particular person, Alice. Economists could predict exactly how much coffee Alice buys if they knew Alice’s income, the price of coffee, some index price for ![]() , and Alice’s indifference curves. However, economists obviously do not know enough to make such quantitative applications.

, and Alice’s indifference curves. However, economists obviously do not know enough to make such quantitative applications.

Knowing little beyond what is stipulated in the assumptions of the model, economists would like to be able to predict or explain changes in consumption as a consequence of changes in prices or income. To do this, further assumptions about the shape of Alice’s indifference curve are necessary. Almost anything is possible in general. A larger income may lead to a smaller demand for inferior goods, and a price decrease can even go with a decrease in demand for “Giffen goods.”Footnote 11 Given indifference curves shaped like those in Figure 2.1, which are reasonable in the case of many consumers and goods such as coffee, more definite conclusions can be reached. If income decreases to ![]() in Figure 2.1, Alice will consume less of both coffee and

in Figure 2.1, Alice will consume less of both coffee and ![]() . If the price of coffee decreases, then Alice will consume more coffee and less of

. If the price of coffee decreases, then Alice will consume more coffee and less of ![]() . Alice’s demand for coffee is a decreasing function of the price of coffee, an increasing function the price of

. Alice’s demand for coffee is a decreasing function of the price of coffee, an increasing function the price of ![]() (which is a substitute), and an increasing function of Alice’s income, and, of course, it depends upon Alice’s preferences. These claims say nothing about the dynamics of adjustment (see §3.4). They state how demand would differ, as it were, after the dust has settled.

(which is a substitute), and an increasing function of Alice’s income, and, of course, it depends upon Alice’s preferences. These claims say nothing about the dynamics of adjustment (see §3.4). They state how demand would differ, as it were, after the dust has settled.

Since market demand is the sum of individual demands, economists can explain the generalizations concerning market demand. And, moreover, just as economists who sought to emulate Newton might have hoped, economists also have corrections for these market generalizations. The theory of consumer choice shows how those generalizations, including even the law of demand, can break down. It would be nice to have a quantitative account of market demand, and it would be nice to make use of a less idealized model, but the descent from the level of market generalization to theoretical underpinnings appears to be a success.

This success is modest, because data concerning market demand provide weak support for consumer choice theory. For example, as Gary Becker has shown (1962), completely random behavior could account for downward-sloping demand curves and the influence of income on demand; and habitual behavior could account for all of the market generalizations discussed earlier. So the theory of consumer choice is only weakly confirmed by its ability to explain the general facts concerning market demand.

2.6 Conclusions

This chapter has sketched the basic components of consumer choice theory and shown how they imply relatively superficial generalizations concerning market demand. In describing the way that microeconomics characterizes the demand side of markets, this account has also been accumulating philosophical debts. It has spoken of rational choice theory and consumer choice theory, without saying much about what constitutes a “theory.” It has taken the fundamental constituents of those theories to be laws, albeit typically with scare quotes, since presumably false claims are not really laws. But I have said nothing about what a law might be. Chapter 1 spoke of models of rational choice, and this chapter delineated one simple model. But little has been said about what a model is or how models, laws, and theories are related. And Section 2.5 ended with some concerns about confirmation, which has also not yet been discussed.