1. Introduction and statement of the results

Euler investigated planar curves of constant density that minimize powers of the moment of inertia with respect to the origin ![]() $0$ [Reference Euler11]. In polar coordinates

$0$ [Reference Euler11]. In polar coordinates ![]() $r=r(s)$, these curves

$r=r(s)$, these curves ![]() $\gamma$ are minimizers of the energy

$\gamma$ are minimizers of the energy  $\int_\gamma r^\alpha\, ds$ for

$\int_\gamma r^\alpha\, ds$ for ![]() $\alpha\in\mathbb R$. Explicit parametrizations of the extremals can be found in [Reference Carathédory4, Reference Tonelli23]. When

$\alpha\in\mathbb R$. Explicit parametrizations of the extremals can be found in [Reference Carathédory4, Reference Tonelli23]. When ![]() $\alpha=2$, the energy represents the moment of inertia with respect to

$\alpha=2$, the energy represents the moment of inertia with respect to ![]() $0$, and the extremals satisfy

$0$, and the extremals satisfy ![]() $ar^3=\mbox{sec}(3\theta+b)$ for constants

$ar^3=\mbox{sec}(3\theta+b)$ for constants ![]() $a,b\in\mathbb R$. For this value

$a,b\in\mathbb R$. For this value ![]() $\alpha=2$, Mason determined the minimizers joining two prescribed points in the plane [Reference Mason18].

$\alpha=2$, Mason determined the minimizers joining two prescribed points in the plane [Reference Mason18].

Recently, the first author and G. Huisken generalized Euler’s problem to arbitrary dimensions [Reference Dierkes and Huisken8]. For surfaces in Euclidean ![]() $3$-space

$3$-space ![]() $\mathbb R^3$, let

$\mathbb R^3$, let ![]() $\Sigma$ be a connected, oriented surface and consider a smooth immersion

$\Sigma$ be a connected, oriented surface and consider a smooth immersion ![]() $\Phi\colon \Sigma\to\mathbb R^3$ in

$\Phi\colon \Sigma\to\mathbb R^3$ in ![]() $\mathbb R^3$. For

$\mathbb R^3$. For ![]() $\alpha\in\mathbb R$, define the energy

$\alpha\in\mathbb R$, define the energy

\begin{equation*}

E_\alpha[\Sigma]=\int_\Sigma |p|^\alpha\, d\Sigma,

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

E_\alpha[\Sigma]=\int_\Sigma |p|^\alpha\, d\Sigma,

\end{equation*} where ![]() $d\Sigma$ denotes the area element induced by the Euclidean metric

$d\Sigma$ denotes the area element induced by the Euclidean metric ![]() $\langle,\rangle$, identifying

$\langle,\rangle$, identifying ![]() $p\in\Sigma$ with its image

$p\in\Sigma$ with its image ![]() $\Phi(p)$. To apply variational techniques, we assume that the origin

$\Phi(p)$. To apply variational techniques, we assume that the origin ![]() $0$ of

$0$ of ![]() $\mathbb R^3$ does not lie on

$\mathbb R^3$ does not lie on ![]() $\Sigma$. The first variation of

$\Sigma$. The first variation of ![]() $E_\alpha$ under compactly supported variations is

$E_\alpha$ under compactly supported variations is

\begin{equation}

E_\alpha'(0)=\int_\Sigma \left( \alpha\frac{\langle\nu(p),p\rangle}{|p|^2}-H(p)\right)|p|^\alpha\xi(p)\, d\Sigma,

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

E_\alpha'(0)=\int_\Sigma \left( \alpha\frac{\langle\nu(p),p\rangle}{|p|^2}-H(p)\right)|p|^\alpha\xi(p)\, d\Sigma,

\end{equation} where ![]() $H$ and

$H$ and ![]() $\nu$ denote the mean curvature and the unit normal vector of

$\nu$ denote the mean curvature and the unit normal vector of ![]() $\Sigma$, respectively, and

$\Sigma$, respectively, and ![]() $\xi$ is the normal component of the variational vector field. Our convention is that

$\xi$ is the normal component of the variational vector field. Our convention is that ![]() $H$ is the sum of the principal curvatures, so a sphere of radius

$H$ is the sum of the principal curvatures, so a sphere of radius ![]() $r \gt 0$ has

$r \gt 0$ has ![]() $H=2/r$ with respect to the inward orientation. From (1.1), we characterize the critical points of

$H=2/r$ with respect to the inward orientation. From (1.1), we characterize the critical points of ![]() $E_\alpha$ as follows.

$E_\alpha$ as follows.

Definition 1.1. A surface ![]() $\Sigma$ of

$\Sigma$ of ![]() $\mathbb R^3-\{0\}$ is said to be a stationary surface of

$\mathbb R^3-\{0\}$ is said to be a stationary surface of ![]() $E_\alpha$ if

$E_\alpha$ if

\begin{equation}

H(p)=\alpha\frac{\langle \nu(p),p\rangle}{|p|^2},\quad p\in\Sigma.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

H(p)=\alpha\frac{\langle \nu(p),p\rangle}{|p|^2},\quad p\in\Sigma.

\end{equation} When ![]() $\alpha=0$, the energy

$\alpha=0$, the energy ![]() $E_0$ coincides with the area functional, and stationary surfaces are minimal surfaces. We shall discard the case

$E_0$ coincides with the area functional, and stationary surfaces are minimal surfaces. We shall discard the case ![]() $\alpha=0$.

$\alpha=0$.

In [Reference Dierkes and Huisken8], the authors studied the stability of spheres and minimal cones, as well as minimizers of ![]() $E_\alpha$; see also [Reference Dierkes7] and extensions to other energies in [Reference Cui and Xu5] and higher codimension in [Reference Morgan19]. As was pointed out in [Reference Dierkes and Huisken8], stationary surfaces for

$E_\alpha$; see also [Reference Dierkes7] and extensions to other energies in [Reference Cui and Xu5] and higher codimension in [Reference Morgan19]. As was pointed out in [Reference Dierkes and Huisken8], stationary surfaces for ![]() $E_\alpha$ can be viewed as critical points of the weighted area on

$E_\alpha$ can be viewed as critical points of the weighted area on ![]() $\mathbb R^3$ with density is

$\mathbb R^3$ with density is ![]() $|p|^\alpha$. Hence, stationary surfaces satisfying (1.2) are weighted minimal surfaces for this density and, in particular, satisfy the maximum principle.

$|p|^\alpha$. Hence, stationary surfaces satisfying (1.2) are weighted minimal surfaces for this density and, in particular, satisfy the maximum principle.

The purpose of this paper is to study and classify all axisymmetric stationary surfaces for the energy ![]() $E_\alpha$. We also revisit the classification of closed stationary surfaces given in [Reference Dierkes and Huisken8], consider compact stationary surfaces with boundary, and finally classify helicoidal stationary surfaces.

$E_\alpha$. We also revisit the classification of closed stationary surfaces given in [Reference Dierkes and Huisken8], consider compact stationary surfaces with boundary, and finally classify helicoidal stationary surfaces.

The paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we provide explicit examples of ![]() $\alpha$-stationary surfaces, namely, vector planes (for all

$\alpha$-stationary surfaces, namely, vector planes (for all ![]() $\alpha$) and spheres (only for

$\alpha$) and spheres (only for ![]() $\alpha=-2,-4$). Using the tangency principle, we prove that the only closed

$\alpha=-2,-4$). Using the tangency principle, we prove that the only closed ![]() $\alpha$-stationary surfaces are spheres centred at the origin (Theorem 2.6), thus completing the classification initiated in [Reference Dierkes and Huisken8]. In Section 3, we apply the tangency principle to compact stationary surfaces with boundary. When

$\alpha$-stationary surfaces are spheres centred at the origin (Theorem 2.6), thus completing the classification initiated in [Reference Dierkes and Huisken8]. In Section 3, we apply the tangency principle to compact stationary surfaces with boundary. When ![]() $\alpha=-2$, we show in Theorem 3.2 that spherical caps are the only compact

$\alpha=-2$, we show in Theorem 3.2 that spherical caps are the only compact ![]() $(-2)$-stationary surfaces with circular boundary.

$(-2)$-stationary surfaces with circular boundary.

Sections 4, 5 and 6 form the core of the paper. We study axisymmetric stationary surfaces and classify those that meet the rotation axis. First, we analyze the relationship between the axis of rotation and the origin. Since the norm ![]() $|p|$ is measured from

$|p|$ is measured from ![]() $0$, the origin plays a distinguished role in (1.2). We prove that, except for spheres passing through the origin (which occur for

$0$, the origin plays a distinguished role in (1.2). We prove that, except for spheres passing through the origin (which occur for ![]() $\alpha=-4$), the rotation axis must pass through

$\alpha=-4$), the rotation axis must pass through ![]() $0$ (Prop. 4.1). In Section 5, we establish the existence of rotational stationary surfaces intersecting the rotation axis. Writing (1.2) in radial coordinates yields a singular equation when the surface meets the axis orthogonally. Using the Banach fixed point theorem, we prove the existence of such solutions (Theorem 5.1). We also prove a removability theorem for isolated singularities of Eq. (1.2) (Theorem 5.2).

$0$ (Prop. 4.1). In Section 5, we establish the existence of rotational stationary surfaces intersecting the rotation axis. Writing (1.2) in radial coordinates yields a singular equation when the surface meets the axis orthogonally. Using the Banach fixed point theorem, we prove the existence of such solutions (Theorem 5.1). We also prove a removability theorem for isolated singularities of Eq. (1.2) (Theorem 5.2).

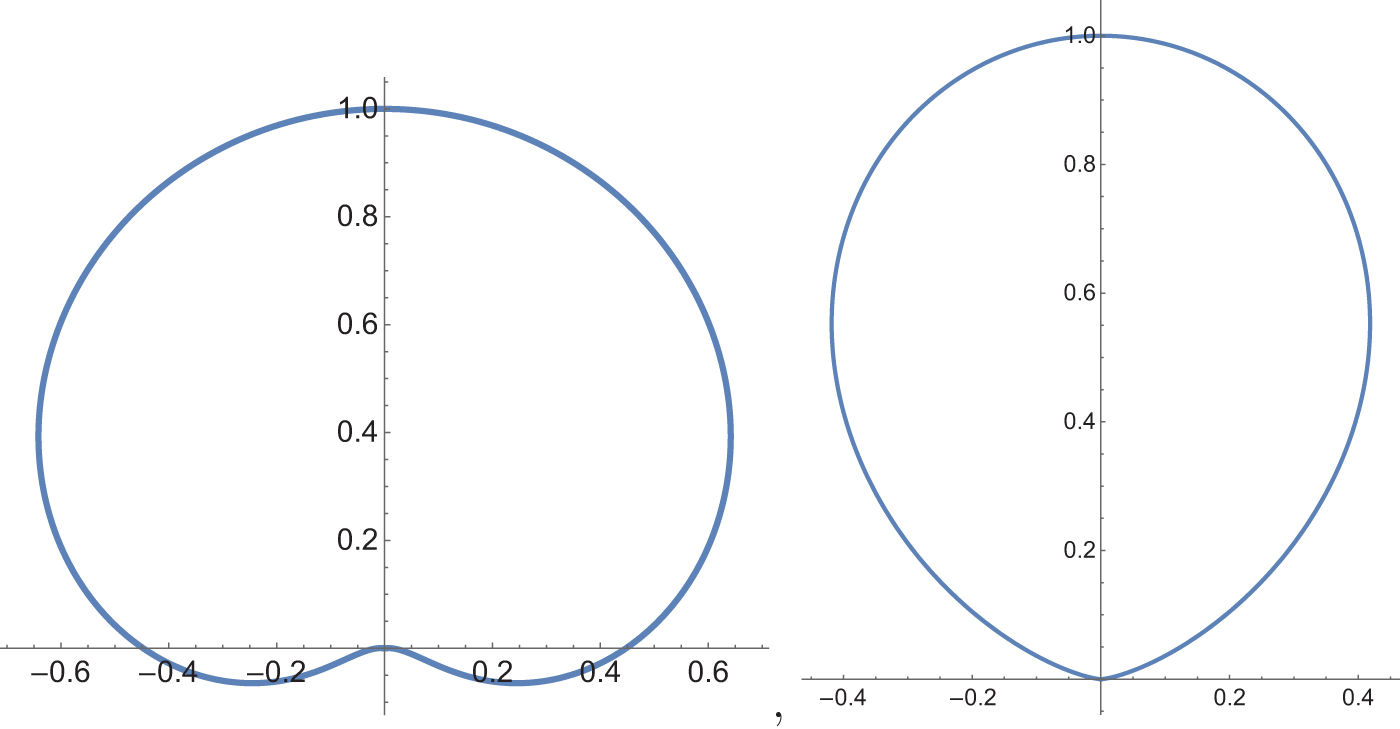

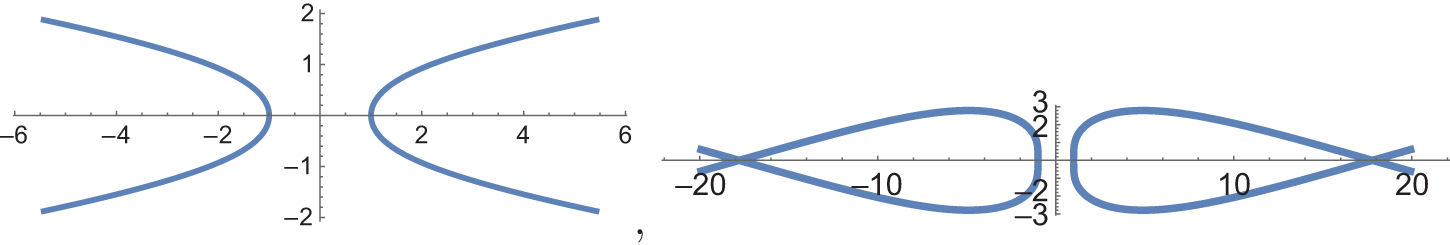

Section 6 provides a classification of axisymmetric stationary surfaces, including a geometric description when they meet the rotation axis: see Theorems 6.1, 6.2, and 6.3. A summary of the classification is as follows.

(i) If

$\alpha \gt 0$, then the surface is an entire graph.

$\alpha \gt 0$, then the surface is an entire graph.(ii) If

$\alpha\in (-2,0)$, then the surface is a graph over a plane outside a compact set around

$\alpha\in (-2,0)$, then the surface is a graph over a plane outside a compact set around  $0$.

$0$.(iii) If

$\alpha=-2$, then the surface is a sphere centred at

$\alpha=-2$, then the surface is a sphere centred at  $0$.

$0$.(iv) If

$\alpha \lt -2$, then the surface together with the origin forms a closed surface that is non-smooth at

$\alpha \lt -2$, then the surface together with the origin forms a closed surface that is non-smooth at  $0$, except when

$0$, except when  $\alpha=-4$, in which case the surface is a sphere. If

$\alpha=-4$, in which case the surface is a sphere. If  $\alpha \lt 4$, this surface is embedded.

$\alpha \lt 4$, this surface is embedded.

In Section 7, we investigate stationary surfaces of helicoidal type. We show that such surfaces are trivial in the sense that the pitch that determines the helicoidal motions must be zero; hence, the only helicoidal stationary surfaces are rotational surfaces (Theorem 7.1).

Recently, the authors have extensively studied the class of stationary surfaces of the energy ![]() $E_\alpha$. The following progress has been made: existence of the Plateau problem [Reference Dierkes and López9], a relationship between

$E_\alpha$. The following progress has been made: existence of the Plateau problem [Reference Dierkes and López9], a relationship between ![]() $\alpha$-stationary surfaces and minimal surfaces [Reference López15], characterization of stationary surfaces with constant Gauss curvature [Reference López16], and classification of ruled stationary surfaces [Reference López17].

$\alpha$-stationary surfaces and minimal surfaces [Reference López15], characterization of stationary surfaces with constant Gauss curvature [Reference López16], and classification of ruled stationary surfaces [Reference López17].

2. Examples of stationary surfaces and the tangency principle

In the first part of this section, we describe the class of transformations of Euclidean space ![]() $\mathbb R^3$ that preserve stationary surfaces, and then we give examples of such surfaces.

$\mathbb R^3$ that preserve stationary surfaces, and then we give examples of such surfaces.

In general, rigid motions of ![]() $\mathbb R^3$ do not preserve solutions of Eq. (1.2) because of the term

$\mathbb R^3$ do not preserve solutions of Eq. (1.2) because of the term ![]() $|p|^2$. This is the case, for example, for translations of

$|p|^2$. This is the case, for example, for translations of ![]() $\mathbb R^3$ or reflections about planes not containing the origin. The following result shows that stationary surfaces are preserved by vector isometries and by dilations about the origin.

$\mathbb R^3$ or reflections about planes not containing the origin. The following result shows that stationary surfaces are preserved by vector isometries and by dilations about the origin.

(i) Let

$A\colon\mathbb R^3\to\mathbb R^3$ be an orthogonal transformation. If

$A\colon\mathbb R^3\to\mathbb R^3$ be an orthogonal transformation. If  $\Sigma$ satisfies (1.2), then

$\Sigma$ satisfies (1.2), then  $A(\Sigma)$ also satisfies (1.2) with the same constant

$A(\Sigma)$ also satisfies (1.2) with the same constant  $\alpha$.

$\alpha$.(ii) Let

$h\colon\mathbb R^3\to\mathbb R^3$ be a dilation centred at

$h\colon\mathbb R^3\to\mathbb R^3$ be a dilation centred at  $0\in\mathbb R^3$. If

$0\in\mathbb R^3$. If  $\Sigma$ satisfies (1.2), then

$\Sigma$ satisfies (1.2), then  $h(\Sigma)$ satisfies (1.2) with the same constant

$h(\Sigma)$ satisfies (1.2) with the same constant  $\alpha$.

$\alpha$.

We now give explicit examples of stationary surfaces, focusing on isoparametric surfaces, namely, planes, spheres, and cylinders, which are precisely the surfaces with constant Gaussian and mean curvature. Among these surfaces, we determine which ones are stationary for the energy ![]() $E_\alpha$.

$E_\alpha$.

Since a plane of ![]() $\mathbb R^3$ has zero mean curvature, a plane

$\mathbb R^3$ has zero mean curvature, a plane ![]() $\Sigma$ is stationary for (1.2) if and only if

$\Sigma$ is stationary for (1.2) if and only if ![]() $\langle\nu(p),p\rangle=0$ for all

$\langle\nu(p),p\rangle=0$ for all ![]() $p\in\Sigma$. This forces the origin to lie in the plane, and hence the plane must be a vector plane.

$p\in\Sigma$. This forces the origin to lie in the plane, and hence the plane must be a vector plane.

Proposition 2.2. A plane of ![]() $\mathbb R^3$ is an

$\mathbb R^3$ is an ![]() $\alpha$-stationary surface if and only if it is a vector plane. This holds for all

$\alpha$-stationary surface if and only if it is a vector plane. This holds for all ![]() $\alpha\in\mathbb R$.

$\alpha\in\mathbb R$.

We now determine which spheres are stationary surfaces.

Proposition 2.3. The only stationary spheres are:

(i) any sphere centred at the origin (

$\alpha=-2$);

$\alpha=-2$);(ii) any sphere passing through the origin (

$\alpha=-4$).

$\alpha=-4$).

Proof. Let ![]() $\Sigma$ be a sphere of radius

$\Sigma$ be a sphere of radius ![]() $r \gt 0$ centred at

$r \gt 0$ centred at ![]() $q=(q_1,q_2,q_3)\in\mathbb R^3$. A parametrization of

$q=(q_1,q_2,q_3)\in\mathbb R^3$. A parametrization of ![]() $\Sigma$ is

$\Sigma$ is

Since ![]() $H=2/r$, substituting into (1.2) yields an identity of the form

$H=2/r$, substituting into (1.2) yields an identity of the form

for some function ![]() $A_0$. Hence,

$A_0$. Hence,

for all ![]() $s\in\mathbb R$. We analyze cases.

$s\in\mathbb R$. We analyze cases.

(i) Case

$\alpha=-4$. Then Eq. (1.2) reduces to

$\alpha=-4$. Then Eq. (1.2) reduces to  $|q|^2-r^2=0$, which says that the sphere contains the origin.

$|q|^2-r^2=0$, which says that the sphere contains the origin.(ii) Case

$\alpha\not=-4$. Then (2.1) implies

$\alpha\not=-4$. Then (2.1) implies  $q_1=q_2=0$. Substituting into (1.2) gives

$q_1=q_2=0$. Substituting into (1.2) gives

\begin{equation*}2q_3^2+(2+\alpha)r^2+rq_3(4+\alpha)\sin s=0.\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}2q_3^2+(2+\alpha)r^2+rq_3(4+\alpha)\sin s=0.\end{equation*}Since this holds for all

$s\in\mathbb R$, we must have

$s\in\mathbb R$, we must have  $2q_3^2+(2+\alpha)r^2=0$ and

$2q_3^2+(2+\alpha)r^2=0$ and  $rq_3(4+\alpha)=0$. It follows that

$rq_3(4+\alpha)=0$. It follows that  $q_3=0$ and

$q_3=0$ and  $\alpha=-2$. Thus

$\alpha=-2$. Thus  $q=0$.

$q=0$.

The converse is immediate: the spheres in (1) and (2) satisfy (1.2).

Note that it is implicitly assumed that the origin does not lie in the vector planes of Prop. 2.2, nor in the spheres of Prop. 2.3. Finally, we show that there are no stationary circular cylinders.

Proposition 2.4. No circular cylinders are stationary surfaces.

Proof. Let ![]() $\Sigma$ be a circular cylinder of radius

$\Sigma$ be a circular cylinder of radius ![]() $r \gt 0$ that also satisfies (1.2). By item (1) of Prop. 2.3 and after a suitable orthogonal transformation of

$r \gt 0$ that also satisfies (1.2). By item (1) of Prop. 2.3 and after a suitable orthogonal transformation of ![]() $\mathbb R^3$, we may assume that the rotation axis of the cylinder is parallel to the

$\mathbb R^3$, we may assume that the rotation axis of the cylinder is parallel to the ![]() $z$-axis and contained in the

$z$-axis and contained in the ![]() $xz$-plane. A parametrization of

$xz$-plane. A parametrization of ![]() $\Sigma$ is

$\Sigma$ is

Since ![]() $H=1/r$, substituting into (1.2) yields

$H=1/r$, substituting into (1.2) yields

This equation is polynomial in ![]() $s$ with leading coefficient

$s$ with leading coefficient ![]() $1$, which is not possible.

$1$, which is not possible.

We now focus on closed ![]() $\alpha$-stationary surfaces. In [Reference Dierkes and Huisken8, Theorem 1.6], the following is proved:

$\alpha$-stationary surfaces. In [Reference Dierkes and Huisken8, Theorem 1.6], the following is proved:

(i) If

$\alpha \gt -2$, then there are no closed stationary surfaces.

$\alpha \gt -2$, then there are no closed stationary surfaces.(ii) If

$\alpha=-2$, then the only stable closed stationary surfaces are spheres centred at the origin.

$\alpha=-2$, then the only stable closed stationary surfaces are spheres centred at the origin.(iii) If

$\alpha \lt -2$ and

$\alpha \lt -2$ and  $\Sigma$ is stationary (closed or not closed), then its closure

$\Sigma$ is stationary (closed or not closed), then its closure  $\overline{\Sigma}$ must contain the origin.

$\overline{\Sigma}$ must contain the origin.

The proofs of (1) and (3) use the maximum principle for the Laplacian of ![]() $p\mapsto |p|$. In the case

$p\mapsto |p|$. In the case ![]() $\alpha=-2$, the statement is proved via the second variation of the energy

$\alpha=-2$, the statement is proved via the second variation of the energy ![]() $E_\alpha$. We now revisit these results using an appropriate maximum principle, removing the stability assumption in (2).

$E_\alpha$. We now revisit these results using an appropriate maximum principle, removing the stability assumption in (2).

Stationary surfaces for the energy ![]() $E_\alpha$ are weighted minimal surfaces in the sense of manifolds with density. In

$E_\alpha$ are weighted minimal surfaces in the sense of manifolds with density. In ![]() $\mathbb R^3$, consider a positive density

$\mathbb R^3$, consider a positive density ![]() $e^\phi\in C^\infty(\mathbb R^3)$ modifying the volume and area forms:

$e^\phi\in C^\infty(\mathbb R^3)$ modifying the volume and area forms: ![]() $dV_\phi=e^\phi dV_0$ and

$dV_\phi=e^\phi dV_0$ and ![]() $dA_\phi=e^\phi dA_0$, where

$dA_\phi=e^\phi dA_0$, where ![]() $dV_0$ and

$dV_0$ and ![]() $dA_0$ are the Euclidean volume and area of

$dA_0$ are the Euclidean volume and area of ![]() $\mathbb R^3$. This is not equivalent to conformally scaling the metric, since

$\mathbb R^3$. This is not equivalent to conformally scaling the metric, since ![]() $\phi$ appears with the same exponent in

$\phi$ appears with the same exponent in ![]() $dV_\phi$ and

$dV_\phi$ and ![]() $dA_\phi$. A surface

$dA_\phi$. A surface ![]() $\Sigma$ is a critical point of

$\Sigma$ is a critical point of ![]() $A_\phi$ under volume-preserving variations if and only if its weighted mean curvature

$A_\phi$ under volume-preserving variations if and only if its weighted mean curvature

is constant, where ![]() $\overline{\nabla}$ is the Euclidean gradient ([Reference Bayle2, Reference Morgan20]). Choosing

$\overline{\nabla}$ is the Euclidean gradient ([Reference Bayle2, Reference Morgan20]). Choosing ![]() $\phi(p)=\alpha\log(|p|)$, the condition

$\phi(p)=\alpha\log(|p|)$, the condition ![]() $H_\phi=0$ coincides with (1.2). Thus, stationary surfaces are weighted minimal surfaces for the density

$H_\phi=0$ coincides with (1.2). Thus, stationary surfaces are weighted minimal surfaces for the density ![]() $\alpha\log(|p|)$. Standard elliptic theory applies to Eq. (2.2): see the general reference [Reference Gilbarg and Trudinger12]. We recall the following comparison principle for surfaces tangent at a point [Reference Pucci and Serrin21]. Let

$\alpha\log(|p|)$. Standard elliptic theory applies to Eq. (2.2): see the general reference [Reference Gilbarg and Trudinger12]. We recall the following comparison principle for surfaces tangent at a point [Reference Pucci and Serrin21]. Let ![]() $\partial\Sigma$ denote the boundary of

$\partial\Sigma$ denote the boundary of ![]() $\Sigma$, and let

$\Sigma$, and let ![]() $\mbox{int}(\Sigma)=\Sigma-\partial\Sigma$ the set of interior points.

$\mbox{int}(\Sigma)=\Sigma-\partial\Sigma$ the set of interior points.

Proposition 2.5. Let ![]() $\Sigma_1$ and

$\Sigma_1$ and ![]() $\Sigma_2$ be oriented surfaces of

$\Sigma_2$ be oriented surfaces of ![]() $\mathbb R^3-\{0\}$ which are tangent at an interior point

$\mathbb R^3-\{0\}$ which are tangent at an interior point ![]() $p\in\Sigma_1\cap\Sigma_2$ with

$p\in\Sigma_1\cap\Sigma_2$ with ![]() $\nu_1(p)=\nu_2(p)$. If

$\nu_1(p)=\nu_2(p)$. If ![]() $\Sigma_1$ lies above

$\Sigma_1$ lies above ![]() $\Sigma_2$ near

$\Sigma_2$ near ![]() $p$ with respect to this normal (denoted by

$p$ with respect to this normal (denoted by ![]() $\Sigma_1\geq \Sigma_2$), then

$\Sigma_1\geq \Sigma_2$), then  $H_\phi^1(p)\geq H_\phi^2(p)$. Moreover, if

$H_\phi^1(p)\geq H_\phi^2(p)$. Moreover, if  $H_\phi^1=H_\phi^2=\mbox{constant}$, then

$H_\phi^1=H_\phi^2=\mbox{constant}$, then ![]() $\Sigma_1$ and

$\Sigma_1$ and ![]() $\Sigma_2$ coincide in a neighbourhood of

$\Sigma_2$ coincide in a neighbourhood of ![]() $p$ (tangency principle). The same holds at boundary points

$p$ (tangency principle). The same holds at boundary points ![]() $p$ provided

$p$ provided ![]() $\partial\Sigma_1$ and

$\partial\Sigma_1$ and ![]() $\partial \Sigma_2$ are tangent at

$\partial \Sigma_2$ are tangent at ![]() $p$.

$p$.

If both surfaces satisfy ![]() $H_\phi=0$, the orientation is irrelevant, since reversing the normal preserves the equation. We now apply the tangency principle.

$H_\phi=0$, the orientation is irrelevant, since reversing the normal preserves the equation. We now apply the tangency principle.

In the theory of surfaces with constant mean curvature, the tangency principle is used in Alexandrov’s reflection method, which shows that spheres are the only embedded closed surfaces [Reference Alexandrov1]. This method does not apply here, since reflections do not preserve (1.2) (see Prop. 2.1). By comparison with spheres centred at the origin, we obtain an alternative proof of Theorem 1.6 of [Reference Dierkes and Huisken8] and strengthen the case ![]() $\alpha=-2$ by removing the stability assumption.

$\alpha=-2$ by removing the stability assumption.

Theorem 2.6. Spheres centred at the origin are the only closed ![]() $\alpha$-stationary surfaces.

$\alpha$-stationary surfaces.

Proof. Let ![]() $\Sigma$ be a closed

$\Sigma$ be a closed ![]() $\alpha$-stationary surface. Choose

$\alpha$-stationary surface. Choose ![]() $r \gt 0$ large enough so that

$r \gt 0$ large enough so that ![]() $ \Sigma$ lies inside the ball bounded by the sphere

$ \Sigma$ lies inside the ball bounded by the sphere ![]() $\mathbb S^2(r)$ of radius

$\mathbb S^2(r)$ of radius ![]() $r \gt 0$ centred at the origin. Let

$r \gt 0$ centred at the origin. Let ![]() $r\searrow 0$ until the first contact point occurs at some point

$r\searrow 0$ until the first contact point occurs at some point ![]() $p\in\Sigma\cap \mathbb S^2(r_0)$. Consider the weighted mean curvature

$p\in\Sigma\cap \mathbb S^2(r_0)$. Consider the weighted mean curvature ![]() $H_\phi$ given in (2.2). With respect to the inward orientation on

$H_\phi$ given in (2.2). With respect to the inward orientation on ![]() $\mathbb S^2(r)$, we have

$\mathbb S^2(r)$, we have

\begin{equation*}H_\phi^{\mathbb S^2(r_0)}(p)=\frac{2}{r_0}-\alpha\frac{\langle\nu(p),p\rangle}{|p|^2}=\frac{2+\alpha}{r_0}.\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}H_\phi^{\mathbb S^2(r_0)}(p)=\frac{2}{r_0}-\alpha\frac{\langle\nu(p),p\rangle}{|p|^2}=\frac{2+\alpha}{r_0}.\end{equation*} For ![]() $\Sigma$, we have

$\Sigma$, we have  $H_\phi^\Sigma=0$ for either orientation. Since

$H_\phi^\Sigma=0$ for either orientation. Since ![]() $\Sigma\geq \mathbb S^2(r_0)$ near

$\Sigma\geq \mathbb S^2(r_0)$ near ![]() $p$, the comparison principle gives

$p$, the comparison principle gives

\begin{equation*}0\geq \frac{2+\alpha}{r_0},\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}0\geq \frac{2+\alpha}{r_0},\end{equation*} so ![]() $\alpha\leq -2$.

$\alpha\leq -2$.

If ![]() $\alpha=-2$, the tangency principle implies that

$\alpha=-2$, the tangency principle implies that ![]() $\mathbb S^2(r_0)$ and

$\mathbb S^2(r_0)$ and ![]() $\Sigma$ coincide in an open set around

$\Sigma$ coincide in an open set around ![]() $p$, and by connectedness,

$p$, and by connectedness, ![]() $\mathbb S^2(r_0)=\Sigma$.

$\mathbb S^2(r_0)=\Sigma$.

Finally, assume ![]() $\alpha \lt -2$. Choose

$\alpha \lt -2$. Choose ![]() $r \gt 0$ small so that

$r \gt 0$ small so that ![]() $\mathbb S^2(r)\cap\Sigma=\emptyset$, and increase

$\mathbb S^2(r)\cap\Sigma=\emptyset$, and increase ![]() $r\nearrow\infty $ until the first contact with

$r\nearrow\infty $ until the first contact with ![]() $\Sigma$ at

$\Sigma$ at ![]() $r=r_1$. With the inward orientation on

$r=r_1$. With the inward orientation on ![]() $\mathbb S^2(r_1)$, we have

$\mathbb S^2(r_1)$, we have ![]() $\mathbb S^2(r_1)\geq \Sigma$ around the contact point and the comparison principle yields

$\mathbb S^2(r_1)\geq \Sigma$ around the contact point and the comparison principle yields

\begin{equation*}\frac{2+\alpha}{r_1}\geq 0,\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}\frac{2+\alpha}{r_1}\geq 0,\end{equation*} which implies ![]() $\alpha\geq -2$, a contradiction.

$\alpha\geq -2$, a contradiction.

The last part in the proof implies the following (cf. [Reference Dierkes and Huisken8, Theorem 1.6]).

Corollary 2.7. Let ![]() $\Sigma$ be a properly immersed

$\Sigma$ be a properly immersed ![]() $\alpha$-stationary surface. If

$\alpha$-stationary surface. If ![]() $\alpha \lt -2$, then the closure of

$\alpha \lt -2$, then the closure of ![]() $\Sigma$ contains the origin.

$\Sigma$ contains the origin.

3. Applications of the tangency principle

Once the class of closed stationary surfaces is fully classified, it is natural to study compact stationary surfaces with boundary. As usual, a surface ![]() $\Sigma$ is said to span a curve

$\Sigma$ is said to span a curve ![]() $\Gamma\subset\mathbb R^3$ if there exists an immersion

$\Gamma\subset\mathbb R^3$ if there exists an immersion ![]() $\Phi\colon\Sigma\to\mathbb R^3$ such that

$\Phi\colon\Sigma\to\mathbb R^3$ such that ![]() $\Phi_{|\partial\Sigma}\colon\partial\Sigma\to\Gamma$ is a diffeomorphism. The simplest boundary curve is a circle. There exist examples of compact

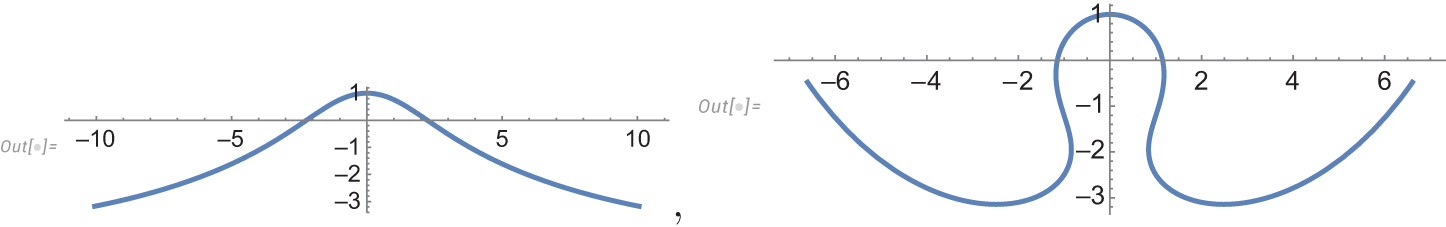

$\Phi_{|\partial\Sigma}\colon\partial\Sigma\to\Gamma$ is a diffeomorphism. The simplest boundary curve is a circle. There exist examples of compact ![]() $\alpha$-stationary surfaces spanning a circle: round discs in vector planes (for all

$\alpha$-stationary surfaces spanning a circle: round discs in vector planes (for all ![]() $\alpha$) and spherical caps in spheres (

$\alpha$) and spherical caps in spheres (![]() $\alpha=-2,-4$). As we will prove in Section 5, there are rotational compact stationary surfaces spanning circles for other values of

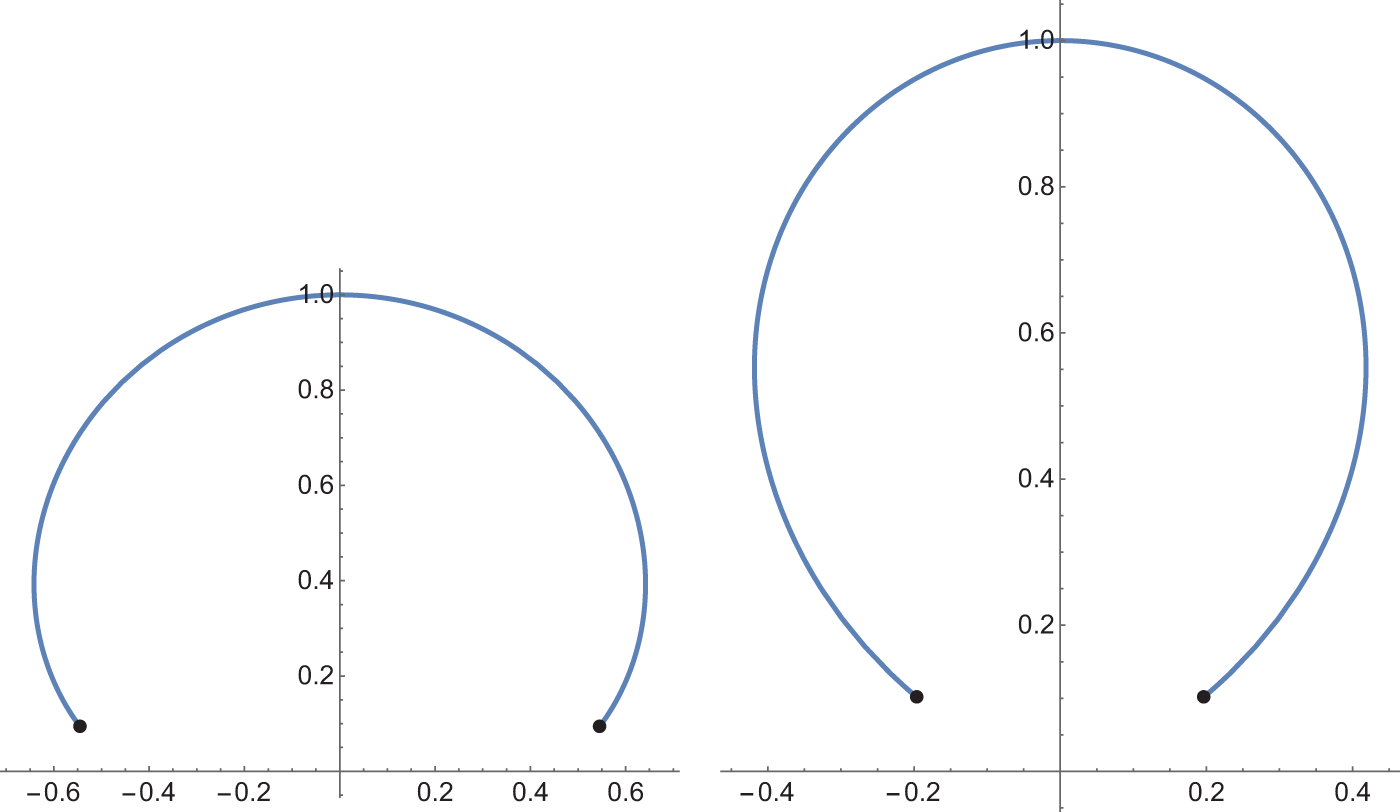

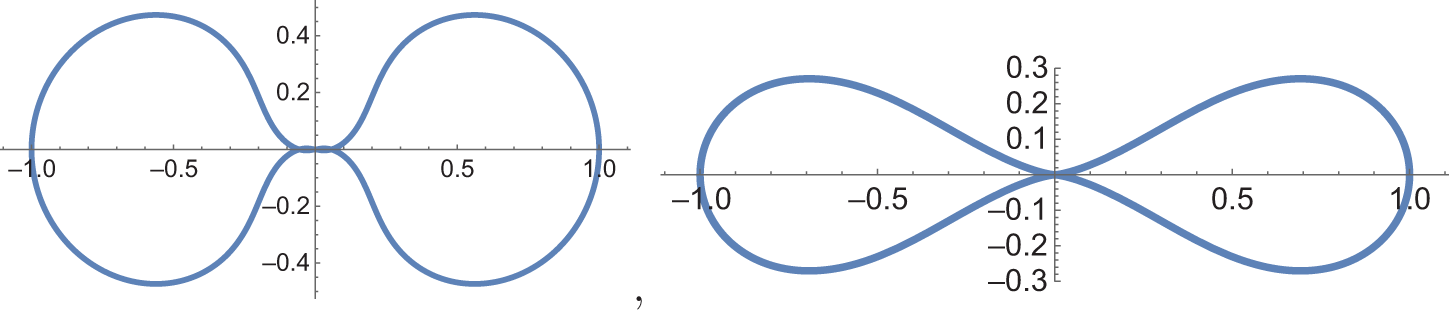

$\alpha=-2,-4$). As we will prove in Section 5, there are rotational compact stationary surfaces spanning circles for other values of ![]() $\alpha$, obtained by taking appropriate pieces of rotational stationary surfaces intersecting the rotation axis orthogonally: see Fig. 1. Note again that the Alexandrov reflection method cannot be applied to conclude rotational symmetry of such surfaces.

$\alpha$, obtained by taking appropriate pieces of rotational stationary surfaces intersecting the rotation axis orthogonally: see Fig. 1. Note again that the Alexandrov reflection method cannot be applied to conclude rotational symmetry of such surfaces.

Figure 1. Rotational stationary surfaces with circular boundary (black points). Here, ![]() $\alpha=-3$ (left) and

$\alpha=-3$ (left) and ![]() $\alpha=-5$ (right).

$\alpha=-5$ (right).

When ![]() $\alpha=-2$, circles lying in spheres centred at the origin are rotationally symmetric about any axis through the origin. When

$\alpha=-2$, circles lying in spheres centred at the origin are rotationally symmetric about any axis through the origin. When ![]() $\alpha=-4$, circles lying in spheres passing through the origin are also rotationally symmetric, but the rotation axis need not pass through the origin.

$\alpha=-4$, circles lying in spheres passing through the origin are also rotationally symmetric, but the rotation axis need not pass through the origin.

In a broader context, we may ask how the geometry of a given curve in ![]() $\mathbb R^3$ determines the geometry of the stationary surfaces that it spans. In this sense, the comparison and tangency principles allow one to control the shape of the surface in terms of the geometry of its boundary. The next result is illustrative.

$\mathbb R^3$ determines the geometry of the stationary surfaces that it spans. In this sense, the comparison and tangency principles allow one to control the shape of the surface in terms of the geometry of its boundary. The next result is illustrative.

Proposition 3.1. Let ![]() $\Sigma$ be a compact

$\Sigma$ be a compact ![]() $\alpha$-stationary surface whose boundary is a circle centred on the

$\alpha$-stationary surface whose boundary is a circle centred on the ![]() $z$-axis and lying in a horizontal plane. If

$z$-axis and lying in a horizontal plane. If ![]() $\alpha \gt -1$, then

$\alpha \gt -1$, then ![]() $\Sigma$ is contained in the vertical cylinder

$\Sigma$ is contained in the vertical cylinder ![]() $D\times\mathbb R$, where

$D\times\mathbb R$, where ![]() $D$ is the horizontal round disc bounded by

$D$ is the horizontal round disc bounded by ![]() $\partial\Sigma$.

$\partial\Sigma$.

Proof. Let ![]() $C_r$ denote the circular cylinder of radius

$C_r$ denote the circular cylinder of radius ![]() $r \gt 0$ with axis the

$r \gt 0$ with axis the ![]() $z$-axis. With respect to its inward orientation,

$z$-axis. With respect to its inward orientation,

\begin{equation*}H_\phi^{C_r}(p)=\frac{1}{r}-\alpha\frac{\langle\nu(p),p\rangle}{|p|^2}=\frac{|p|^2+\alpha r^2}{r|p|^2}=

\frac{(1+\alpha)r^2+z^2}{r|p|^2}.\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}H_\phi^{C_r}(p)=\frac{1}{r}-\alpha\frac{\langle\nu(p),p\rangle}{|p|^2}=\frac{|p|^2+\alpha r^2}{r|p|^2}=

\frac{(1+\alpha)r^2+z^2}{r|p|^2}.\end{equation*} If ![]() $\alpha \gt -1$, then

$\alpha \gt -1$, then  $H_\phi^{C_r} \gt 0$.

$H_\phi^{C_r} \gt 0$.

Choose ![]() $r$ large enough so that

$r$ large enough so that ![]() $\Sigma$ lies inside the region bounded by

$\Sigma$ lies inside the region bounded by ![]() $C_r$. Decrease

$C_r$. Decrease ![]() $r$,

$r$, ![]() $r\searrow 0$, until the first contact at

$r\searrow 0$, until the first contact at ![]() $r=r_0$. If the touching point lies in

$r=r_0$. If the touching point lies in ![]() $\mathrm{int}(\Sigma)$, orient

$\mathrm{int}(\Sigma)$, orient ![]() $\Sigma$ so that

$\Sigma$ so that ![]() $\Sigma\geq C_{r_0}$ near

$\Sigma\geq C_{r_0}$ near ![]() $p$. The comparison principle yields

$p$. The comparison principle yields  $0\geq H_\phi^{C_{r_0}}$, but

$0\geq H_\phi^{C_{r_0}}$, but  $H_\phi^{C_{r_0}}$ is positive which it is a contradiction. Therefore, the first contact occurs at

$H_\phi^{C_{r_0}}$ is positive which it is a contradiction. Therefore, the first contact occurs at ![]() $\partial\Sigma$. Since

$\partial\Sigma$. Since ![]() $\partial\Sigma$ is a circle contained in

$\partial\Sigma$ is a circle contained in ![]() $C_{r_0}$, the conclusion follows.

$C_{r_0}$, the conclusion follows.

Figure 1 illustrates examples of compact ![]() $\alpha$-stationary surfaces spanning a circle that are not contained in

$\alpha$-stationary surfaces spanning a circle that are not contained in ![]() $D\times\mathbb R$: this occurs for

$D\times\mathbb R$: this occurs for ![]() $\alpha \lt -1$.

$\alpha \lt -1$.

Using spheres instead of cylinders, we obtain the following uniqueness result.

Theorem 3.2. If ![]() $\alpha=-2$, spherical caps are the only compact stationary surfaces bounded by a circle whose rotation axis passes through the origin.

$\alpha=-2$, spherical caps are the only compact stationary surfaces bounded by a circle whose rotation axis passes through the origin.

Proof. Let ![]() $\Gamma\subset\mathbb R^3$ be a circle whose rotation axis passes through the origin. Then

$\Gamma\subset\mathbb R^3$ be a circle whose rotation axis passes through the origin. Then ![]() $\Gamma$ lies on a sphere

$\Gamma$ lies on a sphere ![]() $\mathbb S^2(r_1)$ of radius

$\mathbb S^2(r_1)$ of radius ![]() $r_1 \gt 0$. Let

$r_1 \gt 0$. Let ![]() $\Sigma$ be a compact

$\Sigma$ be a compact ![]() $(-2)$-stationary surface spanning

$(-2)$-stationary surface spanning ![]() $\Gamma$. As in the proof of Theorem 2.6, choose

$\Gamma$. As in the proof of Theorem 2.6, choose ![]() $r \gt 0$ large enough so that

$r \gt 0$ large enough so that ![]() $\Sigma$ is contained inside

$\Sigma$ is contained inside ![]() $\mathbb S^2(r)$, and decrease

$\mathbb S^2(r)$, and decrease ![]() $r\searrow 0$ until the first contact occurs at

$r\searrow 0$ until the first contact occurs at ![]() $r_0\geq r_1$.

$r_0\geq r_1$.

(i) If the contact point is interior to

$\Sigma$, the tangency principle implies that

$\Sigma$, the tangency principle implies that  $\Sigma\subset\mathbb S^2(r_0)$ and

$\Sigma\subset\mathbb S^2(r_0)$ and  $r_0=r_1$. Since

$r_0=r_1$. Since  $\Gamma$ is a circle, then

$\Gamma$ is a circle, then  $\Sigma$ is a spherical cap.

$\Sigma$ is a spherical cap.(ii) If the contact point lies on

$\partial\Sigma$ and the tangent planes agree, then again

$\partial\Sigma$ and the tangent planes agree, then again  $\Sigma$ is a spherical cap. In both cases, the result is proved.

$\Sigma$ is a spherical cap. In both cases, the result is proved.

Suppose instead that at ![]() $r=r_1$, the spheres first meet

$r=r_1$, the spheres first meet ![]() $\Sigma$ at a boundary point where the tangent planes do not agree. Then

$\Sigma$ at a boundary point where the tangent planes do not agree. Then ![]() $ \mbox{int}(\Sigma)$ lies inside the round ball determined by

$ \mbox{int}(\Sigma)$ lies inside the round ball determined by ![]() $\mathbb S^2(r_1)$. We prove that this situation is not possible. Choose

$\mathbb S^2(r_1)$. We prove that this situation is not possible. Choose ![]() $r$ small so that

$r$ small so that ![]() $\Sigma$ lies outside

$\Sigma$ lies outside ![]() $\mathbb S^2(r)$, and increase

$\mathbb S^2(r)$, and increase ![]() $r$,

$r$, ![]() $r\nearrow\infty$, until the first contact at

$r\nearrow\infty$, until the first contact at ![]() $r=r_2$. By assumption

$r=r_2$. By assumption ![]() $r_2 \lt r_1$ because we are assuming that

$r_2 \lt r_1$ because we are assuming that ![]() $\mbox{int}(\Sigma)\cap\mathbb S^2(r_1)=\emptyset$. Since the first contact between

$\mbox{int}(\Sigma)\cap\mathbb S^2(r_1)=\emptyset$. Since the first contact between ![]() $\Sigma$ and

$\Sigma$ and ![]() $\mathbb S^2(r_1)$ is interior, the tangency principle applied to the stationary surfaces

$\mathbb S^2(r_1)$ is interior, the tangency principle applied to the stationary surfaces ![]() $\Sigma$ and

$\Sigma$ and ![]() $\mathbb S^2(r_2)$ yields

$\mathbb S^2(r_2)$ yields ![]() $\Sigma\subset\mathbb S^2(r_2)$ and

$\Sigma\subset\mathbb S^2(r_2)$ and ![]() $\Sigma$ is a spherical cap of

$\Sigma$ is a spherical cap of ![]() $\mathbb S^2(r_2)$. This is a contradiction because

$\mathbb S^2(r_2)$. This is a contradiction because ![]() $r_1\not= r_2$.

$r_1\not= r_2$.

In the theory of elliptic equations, the maximum principle is also used to ensure the uniqueness of solutions to the Dirichlet problem. However, this is not true in general for Eq. (1.2), because translations of ![]() $\mathbb R^3$ do not preserve its solutions. Instead, for arguments of this type, planar graphs and radial graphs are appropriate, since solutions of (1.2) are preserved by dilations.

$\mathbb R^3$ do not preserve its solutions. Instead, for arguments of this type, planar graphs and radial graphs are appropriate, since solutions of (1.2) are preserved by dilations.

Proposition 3.3. Let ![]() $\Omega$ be a domain of the unit sphere

$\Omega$ be a domain of the unit sphere ![]() $\mathbb S^2$, and let

$\mathbb S^2$, and let ![]() $\varphi\in C^\infty(\partial\Omega)$ with

$\varphi\in C^\infty(\partial\Omega)$ with ![]() $\varphi \gt 0$. Then there is at most one stationary radial graph on

$\varphi \gt 0$. Then there is at most one stationary radial graph on ![]() $\Omega$ with boundary data

$\Omega$ with boundary data ![]() $\varphi$.

$\varphi$.

Proof. Let ![]() $\Gamma$ be the radial graph of

$\Gamma$ be the radial graph of ![]() $\varphi$. Suppose

$\varphi$. Suppose ![]() $\Sigma_1$ and

$\Sigma_1$ and ![]() $\Sigma_2$ are two stationary radial graphs over

$\Sigma_2$ are two stationary radial graphs over ![]() $\Omega$ with

$\Omega$ with ![]() $\partial\Sigma_1=\partial\Sigma_2=\Gamma$. Let

$\partial\Sigma_1=\partial\Sigma_2=\Gamma$. Let ![]() $h_t$ denote the dilation of

$h_t$ denote the dilation of ![]() $\mathbb R^3$ with ratio

$\mathbb R^3$ with ratio ![]() $t \gt 0$ and let

$t \gt 0$ and let ![]() $\Sigma_2^t=h_t(\Sigma_2)$. By Prop. 2.1,

$\Sigma_2^t=h_t(\Sigma_2)$. By Prop. 2.1, ![]() $\Sigma_2^t$ is an

$\Sigma_2^t$ is an ![]() $\alpha$-stationary surface. For

$\alpha$-stationary surface. For ![]() $t$ sufficiently large, we have

$t$ sufficiently large, we have ![]() $\Sigma_2^t\cap\Sigma_1=\emptyset$. Let

$\Sigma_2^t\cap\Sigma_1=\emptyset$. Let ![]() $t\searrow 0$ until the first contact point with

$t\searrow 0$ until the first contact point with ![]() $\Sigma_1$, occurring at

$\Sigma_1$, occurring at ![]() $t=t_0$. Note that

$t=t_0$. Note that ![]() $t_0\geq 1$. Applying the arguments of Theorem 3.2, we conclude that

$t_0\geq 1$. Applying the arguments of Theorem 3.2, we conclude that ![]() $t_0=1$, hence

$t_0=1$, hence ![]() $\Sigma_1=\Sigma_2$. We omit the details.

$\Sigma_1=\Sigma_2$. We omit the details.

We conclude this section by revisiting Theorem 2.6 for ![]() $\alpha\geq -2$. We provide a proof that uses only the divergence theorem, a simpler tool than the tangency principle

$\alpha\geq -2$. We provide a proof that uses only the divergence theorem, a simpler tool than the tangency principle

(i) If

$\alpha \gt -2$, there are no closed stationary surfaces.

$\alpha \gt -2$, there are no closed stationary surfaces.(ii) If

$\alpha=-2$, spheres centred at

$\alpha=-2$, spheres centred at  $0$ are the only closed stationary surfaces.

$0$ are the only closed stationary surfaces.

Proof. For any surface ![]() $\Sigma\subset\mathbb R^3$, the Laplacian of the restriction of the function

$\Sigma\subset\mathbb R^3$, the Laplacian of the restriction of the function ![]() $p\mapsto |p|^2$ to

$p\mapsto |p|^2$ to ![]() $\Sigma$ satisfies

$\Sigma$ satisfies

If ![]() $\Sigma$ is an

$\Sigma$ is an ![]() $\alpha$-stationary surface, Eq. (1.2) gives

$\alpha$-stationary surface, Eq. (1.2) gives

\begin{equation}

\Delta|p|^2=4+2\alpha\frac{\langle\nu(p),p\rangle^2}{|p|^2}.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\Delta|p|^2=4+2\alpha\frac{\langle\nu(p),p\rangle^2}{|p|^2}.

\end{equation}(i) Suppose

$\Sigma $ is closed and

$\Sigma $ is closed and  $\alpha \gt -2$. Integrating (3.1) over

$\alpha \gt -2$. Integrating (3.1) over  $\Sigma$ and applying the divergence theorem, we obtain

$\Sigma$ and applying the divergence theorem, we obtain

\begin{equation*}0=\int_\Sigma \left(4+2\alpha\frac{\langle\nu(p),p\rangle^2}{|p|^2}\right)\, d\Sigma=2\int_\Sigma \frac{2|p|^2+\alpha \langle\nu(p),p\rangle^2}{|p|^2}\, d\Sigma.\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}0=\int_\Sigma \left(4+2\alpha\frac{\langle\nu(p),p\rangle^2}{|p|^2}\right)\, d\Sigma=2\int_\Sigma \frac{2|p|^2+\alpha \langle\nu(p),p\rangle^2}{|p|^2}\, d\Sigma.\end{equation*}If

$\alpha\geq 0$, the integrand is strictly positive, a contradiction. If

$\alpha\geq 0$, the integrand is strictly positive, a contradiction. If  $-2 \lt \alpha \lt 0$, then since

$-2 \lt \alpha \lt 0$, then since  $\langle\nu(p),p\rangle^2\leq |p|^2$ and

$\langle\nu(p),p\rangle^2\leq |p|^2$ and  $\alpha \lt 0$, we have

$\alpha \lt 0$, we have

\begin{equation*}\alpha\langle \nu(p),p\rangle^2\geq\alpha|p|^2.\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}\alpha\langle \nu(p),p\rangle^2\geq\alpha|p|^2.\end{equation*}Thus,

\begin{equation*}0= 2\int_\Sigma \left(\frac{2|p|^2+\alpha \langle\nu(p),p\rangle^2}{|p|^2}\right)\, d\Sigma\geq 2(2+\alpha)\mbox{area}(\Sigma) \gt 0,\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}0= 2\int_\Sigma \left(\frac{2|p|^2+\alpha \langle\nu(p),p\rangle^2}{|p|^2}\right)\, d\Sigma\geq 2(2+\alpha)\mbox{area}(\Sigma) \gt 0,\end{equation*}a contradiction.

(ii) If

$\alpha= -2$, the same computation gives

$\alpha= -2$, the same computation gives

\begin{equation*}0= 2\int_\Sigma \frac{2|p|^2-2 \langle\nu(p),p\rangle^2}{|p|^2}\, d\Sigma\geq 0.\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}0= 2\int_\Sigma \frac{2|p|^2-2 \langle\nu(p),p\rangle^2}{|p|^2}\, d\Sigma\geq 0.\end{equation*}Therefore

$\langle\nu(p),p\rangle^2=|p|^2$ for all

$\langle\nu(p),p\rangle^2=|p|^2$ for all  $p\in\Sigma$, which implies that

$p\in\Sigma$, which implies that  $\Sigma$ is a sphere centred at the origin.

$\Sigma$ is a sphere centred at the origin.

4. The rotation axis of a stationary rotational surface

In the next sections, we investigate axisymmetric stationary surfaces, i.e., stationary surfaces invariant under a one-parametric group of rotations of ![]() $\mathbb R^3$. In the definition of the energy

$\mathbb R^3$. In the definition of the energy ![]() $E_\alpha$, the origin

$E_\alpha$, the origin ![]() $0\in\mathbb R^3$ is a distinguished point because the moment of inertia is computed with respect to

$0\in\mathbb R^3$ is a distinguished point because the moment of inertia is computed with respect to ![]() $0\in\mathbb R^3$. A priori, there is no necessary relation between the rotation axis of an axisymmetric stationary surface and the origin. For example, if

$0\in\mathbb R^3$. A priori, there is no necessary relation between the rotation axis of an axisymmetric stationary surface and the origin. For example, if ![]() $\alpha=-4$, we know that any sphere containing the origin is stationary; such a sphere is a surface of revolution with respect to any line through its centre, and this line need not pass through

$\alpha=-4$, we know that any sphere containing the origin is stationary; such a sphere is a surface of revolution with respect to any line through its centre, and this line need not pass through ![]() $0$. However, in the next result, we show that this is the only exception.

$0$. However, in the next result, we show that this is the only exception.

Proposition 4.1. Let ![]() $\Sigma$ be an axisymmetric surface about an axis

$\Sigma$ be an axisymmetric surface about an axis ![]() $L$. If

$L$. If ![]() $\Sigma$ is stationary, then either

$\Sigma$ is stationary, then either ![]() $0\in L$ or

$0\in L$ or ![]() $\Sigma$ is a sphere containing

$\Sigma$ is a sphere containing ![]() $0$.

$0$.

Proof. Using Prop. 2.1, and applying an isometry of ![]() $\mathbb R^3$, we may assume that the rotation axis

$\mathbb R^3$, we may assume that the rotation axis ![]() $L$ is parallel to the

$L$ is parallel to the ![]() $z$-axis and contained in the

$z$-axis and contained in the ![]() $xz$-plane coordinate. Thus

$xz$-plane coordinate. Thus ![]() $L$ is given by the equations

$L$ is given by the equations ![]() $\{x=q_1, y=0\}$ with

$\{x=q_1, y=0\}$ with ![]() $q_1\in\mathbb R$. A parametrization of

$q_1\in\mathbb R$. A parametrization of ![]() $\Sigma$ is

$\Sigma$ is

where ![]() $\gamma(s)=(x(s),0,z(s))$,

$\gamma(s)=(x(s),0,z(s))$, ![]() $s\in I\subset\mathbb R$, is the generating curve of

$s\in I\subset\mathbb R$, is the generating curve of ![]() $\Sigma$. We must prove that either

$\Sigma$. We must prove that either ![]() $q_1=0$ (and hence

$q_1=0$ (and hence ![]() $0\in L$) or that

$0\in L$) or that ![]() $\Sigma$ is a sphere containing

$\Sigma$ is a sphere containing ![]() $0$.

$0$.

Without loss of generality, we assume that ![]() $\gamma$ is parametrized by arc-length. Since

$\gamma$ is parametrized by arc-length. Since ![]() $x'(s)^2+z'(s)^2=1$, there exists a smooth function

$x'(s)^2+z'(s)^2=1$, there exists a smooth function ![]() $\psi$ such that

$\psi$ such that

\begin{equation*}

\begin{aligned}

x'(s)&=\cos\psi(s),\\

z'(s)&=\sin\psi(s).

\end{aligned}

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\begin{aligned}

x'(s)&=\cos\psi(s),\\

z'(s)&=\sin\psi(s).

\end{aligned}

\end{equation*} We compute the terms appearing in the stationary surface equation (1.2). The unit normal vector of ![]() $\Sigma$ is

$\Sigma$ is

The principal curvatures are

\begin{equation}

\kappa_1=\psi',\quad \kappa_2=\frac{\sin\psi}{x},

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\kappa_1=\psi',\quad \kappa_2=\frac{\sin\psi}{x},

\end{equation}and so the mean curvature is

\begin{equation*}H=\psi'+\frac{\sin\psi}{x}.\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}H=\psi'+\frac{\sin\psi}{x}.\end{equation*}Equation (1.2) becomes

where

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

A_1 &=xq_1(2x\psi'+(2+\alpha)\sin\psi)\\

A_0&=\sin \psi \left(q_1^2+(\alpha +1) x^2+z^2\right)+x \psi ' (q_1^2+x^2+z^2)-\alpha x z \cos \psi .

\end{aligned}

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

A_1 &=xq_1(2x\psi'+(2+\alpha)\sin\psi)\\

A_0&=\sin \psi \left(q_1^2+(\alpha +1) x^2+z^2\right)+x \psi ' (q_1^2+x^2+z^2)-\alpha x z \cos \psi .

\end{aligned}

\end{equation} Thus ![]() $A_0(s)=A_1(s)=0$ for all

$A_0(s)=A_1(s)=0$ for all ![]() $s\in I$. From

$s\in I$. From ![]() $A_1=0$, we have two possibilities. If

$A_1=0$, we have two possibilities. If ![]() $q_1=0$, then the rotation axis is the

$q_1=0$, then the rotation axis is the ![]() $z$-axis, which contains the origin. This gives the result in this case.

$z$-axis, which contains the origin. This gives the result in this case.

Assume now that ![]() $q_1\not=0$. Then

$q_1\not=0$. Then ![]() $A_1=0$ implies

$A_1=0$ implies

identically in ![]() $I$, that is,

$I$, that is,

\begin{equation}

\psi'=-\frac{(2+\alpha)\sin\psi}{2x}.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\psi'=-\frac{(2+\alpha)\sin\psi}{2x}.

\end{equation} Substituting this expression for ![]() $\psi'$ in

$\psi'$ in ![]() $A_0$, we obtain

$A_0$, we obtain

We now solve this equation. Since the analysis is local, let us write ![]() $\gamma$ as a graph on the

$\gamma$ as a graph on the ![]() $z$-axis. First, we must ensure that

$z$-axis. First, we must ensure that ![]() $\sin\psi\not=0$. If

$\sin\psi\not=0$. If ![]() $\sin\psi=0$ identically, then

$\sin\psi=0$ identically, then ![]() $z=z(s)$ is constant, so

$z=z(s)$ is constant, so ![]() $\gamma$ is a horizontal line and

$\gamma$ is a horizontal line and ![]() $\Sigma$ is a horizontal plane. Since

$\Sigma$ is a horizontal plane. Since ![]() $\Sigma$ is stationary, this plane must be

$\Sigma$ is stationary, this plane must be ![]() $z=0$, which is rotationally symmetric about the

$z=0$, which is rotationally symmetric about the ![]() $z$-axis. This proves the proposition in this case.

$z$-axis. This proves the proposition in this case.

Suppose now that ![]() $\sin\psi\not=0$. We write

$\sin\psi\not=0$. We write ![]() $\gamma$ as the graph of a function

$\gamma$ as the graph of a function ![]() $u$ over the

$u$ over the ![]() $z$-axis by setting

$z$-axis by setting ![]() $r=z$ and

$r=z$ and ![]() $x=u(r)$. Then

$x=u(r)$. Then ![]() $u'=\cot\psi$. We will prove that

$u'=\cot\psi$. We will prove that ![]() $\Sigma$ is a sphere containing

$\Sigma$ is a sphere containing ![]() $0$. Equation (4.4) becomes

$0$. Equation (4.4) becomes

The solution of this ODE is

\begin{equation}

u(r)=\sqrt{q_1^2-r^2+rc},\quad c\in\mathbb R.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

u(r)=\sqrt{q_1^2-r^2+rc},\quad c\in\mathbb R.

\end{equation} Thus, the generating curve of ![]() $\Sigma$ is

$\Sigma$ is ![]() $\gamma(r)=(q_1+u(r),0,r)$. Hence,

$\gamma(r)=(q_1+u(r),0,r)$. Hence, ![]() $\gamma$ is a circle in the

$\gamma$ is a circle in the ![]() $(x,z)$-plane with centre

$(x,z)$-plane with centre ![]() $(q_1,\frac{c}{2})$ and radius

$(q_1,\frac{c}{2})$ and radius  $\frac{\sqrt{c^2+4q_1^2}}{2}$. Consequently,

$\frac{\sqrt{c^2+4q_1^2}}{2}$. Consequently, ![]() $\Sigma$ is a sphere containing

$\Sigma$ is a sphere containing ![]() $0$. This proves the result.

$0$. This proves the result.

Proceeding further, we compute

\begin{equation*}u''=-\frac{\psi'}{\sin^3\psi}.\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}u''=-\frac{\psi'}{\sin^3\psi}.\end{equation*} Since  $\sin^2\psi=\frac{1}{1+u'^2}$, equation (4.3) becomes

$\sin^2\psi=\frac{1}{1+u'^2}$, equation (4.3) becomes

\begin{equation*}\frac{u''}{1+u'^2}=\frac{2+\alpha}{2u}.\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}\frac{u''}{1+u'^2}=\frac{2+\alpha}{2u}.\end{equation*} Substituting the expression (4.5) into this equation leads to ![]() $(4+\alpha)(4q_1^2+c^2)=0,$ which implies

$(4+\alpha)(4q_1^2+c^2)=0,$ which implies ![]() $\alpha=-4$, since

$\alpha=-4$, since ![]() $4q_1^2+c^2 \gt 0$.

$4q_1^2+c^2 \gt 0$.

Remark 4.2. If the rotation axis does not pass through the origin, then necessarily ![]() $\alpha=-4$ and

$\alpha=-4$ and ![]() $\Sigma$ is a sphere. In Section 6, we will show that for

$\Sigma$ is a sphere. In Section 6, we will show that for ![]() $\alpha=-4$ there are non-spherical stationary surfaces that are axisymmetric about the

$\alpha=-4$ there are non-spherical stationary surfaces that are axisymmetric about the ![]() $z$-axis.

$z$-axis.

5. Axisymmetric stationary surfaces intersecting the rotation axis

In this section, we prove the existence of axisymmetric stationary surfaces that intersect the rotation axis orthogonally. Let ![]() $\Sigma$ be such a surface. By Prop. 4.1, the rotation axis passes through the origin. After a linear isometry of

$\Sigma$ be such a surface. By Prop. 4.1, the rotation axis passes through the origin. After a linear isometry of ![]() $\mathbb R^3$ (Prop. 2.1), we may assume that the rotation axis is the

$\mathbb R^3$ (Prop. 2.1), we may assume that the rotation axis is the ![]() $z$-axis.

$z$-axis.

A parametrization of ![]() $\Sigma$ is

$\Sigma$ is

where ![]() $\gamma(s)=(x(s),0,z(s))$ is the generating curve, with

$\gamma(s)=(x(s),0,z(s))$ is the generating curve, with ![]() $x'^2+z'^2=1$. Computing again (1.2), or equivalently using

$x'^2+z'^2=1$. Computing again (1.2), or equivalently using ![]() $A_0=0$ in (4.2), we obtain

$A_0=0$ in (4.2), we obtain

\begin{equation}

\psi'+\frac{\sin\psi}{x} = \alpha\frac{z\cos\psi-x\sin\psi}{x^2+z^2}.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\psi'+\frac{\sin\psi}{x} = \alpha\frac{z\cos\psi-x\sin\psi}{x^2+z^2}.

\end{equation} One naturally expects the existence of solutions intersecting the rotation axis orthogonally. However, Equation (5.1) is singular at ![]() $x=0$ due to the left-hand side, so standard ODE techniques do not guarantee the existence of solutions.

$x=0$ due to the left-hand side, so standard ODE techniques do not guarantee the existence of solutions.

To prove existence, we use a fixed point argument. Since we require that ![]() $\gamma$ meets the

$\gamma$ meets the ![]() $z$-axis orthogonally, we can assume that

$z$-axis orthogonally, we can assume that ![]() $\gamma$ is written as a graph on the

$\gamma$ is written as a graph on the ![]() $x$-axis. Thus, we reparametrize

$x$-axis. Thus, we reparametrize ![]() $\gamma$ as

$\gamma$ as ![]() $\gamma(r)=(r,0,u(r))$, where

$\gamma(r)=(r,0,u(r))$, where ![]() $u=u(r)$ is a smooth function defined on an subinterval of

$u=u(r)$ is a smooth function defined on an subinterval of ![]() $(0,\infty)$. Then Eq. (5.1) becomes

$(0,\infty)$. Then Eq. (5.1) becomes

\begin{equation}

\frac{u''}{(1+u'^2)^{3/2}}+\frac{u'}{r\sqrt{1+u'^2}}= \frac{\alpha(u-ru')}{(r^2+u^2)\sqrt{1+u'^2}}.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\frac{u''}{(1+u'^2)^{3/2}}+\frac{u'}{r\sqrt{1+u'^2}}= \frac{\alpha(u-ru')}{(r^2+u^2)\sqrt{1+u'^2}}.

\end{equation} Multiplying by ![]() $r$, we obtain

$r$, we obtain

\begin{equation*} \left( \dfrac{r u'(r)}{\sqrt{1+u'(r)^2}}\right)'=\alpha\frac{r(u-ru')}{(r^2+u^2) \sqrt{1+u'^2}}.\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*} \left( \dfrac{r u'(r)}{\sqrt{1+u'(r)^2}}\right)'=\alpha\frac{r(u-ru')}{(r^2+u^2) \sqrt{1+u'^2}}.\end{equation*} This equation is singular at ![]() $r=0$. For

$r=0$. For ![]() $r_0\geq 0$, we consider the initial value problem

$r_0\geq 0$, we consider the initial value problem

\begin{equation}

\left\{\begin{array}{ll}

\left( \dfrac{r u'(r)}{\sqrt{1+u'(r)^2}}\right)'=\alpha\dfrac{r(u-ru')}{(r^2+u^2)\sqrt{1+u'^2}} ,&\mbox{in}\ (r_0,r_0+\delta)\\

u(r_0)=u_0& \\

u'(r_0)=0,&

\end{array}\right.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\left\{\begin{array}{ll}

\left( \dfrac{r u'(r)}{\sqrt{1+u'(r)^2}}\right)'=\alpha\dfrac{r(u-ru')}{(r^2+u^2)\sqrt{1+u'^2}} ,&\mbox{in}\ (r_0,r_0+\delta)\\

u(r_0)=u_0& \\

u'(r_0)=0,&

\end{array}\right.

\end{equation} where ![]() $u_0 \gt 0$. The next theorem establishes the existence of axisymmetric stationary surfaces intersecting the rotation axis orthogonally.

$u_0 \gt 0$. The next theorem establishes the existence of axisymmetric stationary surfaces intersecting the rotation axis orthogonally.

Theorem 5.1. For any ![]() $u_0 \gt 0$, the initial value problem (5.3) with

$u_0 \gt 0$, the initial value problem (5.3) with ![]() $r_0=0$ has a solution

$r_0=0$ has a solution ![]() $u\in C^2([0,R])$ for some

$u\in C^2([0,R])$ for some ![]() $R \gt 0$. Moreover, the solution depends continuously on the parameters

$R \gt 0$. Moreover, the solution depends continuously on the parameters ![]() $\alpha$ and

$\alpha$ and ![]() $u_0$.

$u_0$.

Proof. Let ![]() $\mathbb R_0^+=\{r\in\mathbb R\colon r\geq 0\}$. Define

$\mathbb R_0^+=\{r\in\mathbb R\colon r\geq 0\}$. Define

\begin{equation*}f(y)=\frac{y}{\sqrt{1+y^2}},\qquad g(x,y,z)=\frac{\alpha(y-xz)}{(x^2+y^2)\sqrt{1+z^2}},\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}f(y)=\frac{y}{\sqrt{1+y^2}},\qquad g(x,y,z)=\frac{\alpha(y-xz)}{(x^2+y^2)\sqrt{1+z^2}},\end{equation*} with ![]() $f:\mathbb R\rightarrow\mathbb R$ and

$f:\mathbb R\rightarrow\mathbb R$ and ![]() $g:\mathbb R_0^+\times\mathbb R^2\rightarrow\mathbb R$. A function

$g:\mathbb R_0^+\times\mathbb R^2\rightarrow\mathbb R$. A function ![]() $u\in C^2([0,R])$ is a solution of (5.3) if and only if

$u\in C^2([0,R])$ is a solution of (5.3) if and only if

\begin{equation*}\left\{

\begin{aligned}

(r f(u'))'&=r g(r,u,u')\\

u(0)&=u_0\\

u'(0)&=0.

\end{aligned}

\right.

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}\left\{

\begin{aligned}

(r f(u'))'&=r g(r,u,u')\\

u(0)&=u_0\\

u'(0)&=0.

\end{aligned}

\right.

\end{equation*} Integrating and inverting ![]() $f$, we obtain

$f$, we obtain

\begin{equation*}u(r)=u_0+\int_0^rf^{-1}\left(\frac{1}{s}\int_0^s tg(t,u,u')\, dt\right)\, ds.\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}u(r)=u_0+\int_0^rf^{-1}\left(\frac{1}{s}\int_0^s tg(t,u,u')\, dt\right)\, ds.\end{equation*} Fix ![]() $R \gt 0$, to be chosen later. For

$R \gt 0$, to be chosen later. For ![]() $u\in C^1([0,R])$, define the operator

$u\in C^1([0,R])$, define the operator

\begin{equation*}

( \mathsf{T} u)(r)=u_0+\int_0^r f^{-1}\left( \int_0^s\frac{t}{s}g(t,u,u')\, dt\right)\, ds.

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

( \mathsf{T} u)(r)=u_0+\int_0^r f^{-1}\left( \int_0^s\frac{t}{s}g(t,u,u')\, dt\right)\, ds.

\end{equation*} A fixed point of ![]() $ \mathsf{T}$,

$ \mathsf{T}$, ![]() $\mathsf{T}u=u$, solves (5.3). We apply the Banach fixed point theorem in the closed ball

$\mathsf{T}u=u$, solves (5.3). We apply the Banach fixed point theorem in the closed ball ![]() $\overline{\mathcal{B}(u_0,\epsilon)}\subset C^1([0,R])$ for suitably small

$\overline{\mathcal{B}(u_0,\epsilon)}\subset C^1([0,R])$ for suitably small ![]() $\epsilon \gt 0$. Here,

$\epsilon \gt 0$. Here, ![]() $C^1([0,R])$ is endowed with the norm

$C^1([0,R])$ is endowed with the norm ![]() $\|u\|=\|u\|_\infty+\|u'\|_\infty$.

$\|u\|=\|u\|_\infty+\|u'\|_\infty$.

We proceed in three steps.

(i)

$ \mathsf{T}$ is well-defined. Since

$ \mathsf{T}$ is well-defined. Since

\begin{equation*}f^{-1}\colon (-1,1)\to \mathbb R,\quad f^{-1}(x)=\frac{x}{\sqrt{1-x^2}},\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}f^{-1}\colon (-1,1)\to \mathbb R,\quad f^{-1}(x)=\frac{x}{\sqrt{1-x^2}},\end{equation*}we must ensure

\begin{equation*} \left|\int_0^s\frac{t}{s}g(t,u,u')\, dt\right| \lt 1,\mbox{for all}\ r\in [0,R].\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*} \left|\int_0^s\frac{t}{s}g(t,u,u')\, dt\right| \lt 1,\mbox{for all}\ r\in [0,R].\end{equation*}Let

$\epsilon \lt \{1,u_0\}$. We restrict

$\epsilon \lt \{1,u_0\}$. We restrict  $f^{-1}$ to

$f^{-1}$ to  $[-\epsilon,\epsilon]$ and

$[-\epsilon,\epsilon]$ and  $g$ to

$g$ to  $[-\epsilon,\epsilon]\times [u_0-\epsilon,u_0+\epsilon]\times[-\epsilon,\epsilon]$. An upper bound for

$[-\epsilon,\epsilon]\times [u_0-\epsilon,u_0+\epsilon]\times[-\epsilon,\epsilon]$. An upper bound for  $|g|$ is

$|g|$ is

\begin{equation*}|g|\leq \frac{|\alpha|}{(u_0-\epsilon)^2}(u_0+\epsilon+\epsilon^2)\leq \frac{|\alpha|(u_0+2)}{(u_0-\epsilon)^2}:=M.\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}|g|\leq \frac{|\alpha|}{(u_0-\epsilon)^2}(u_0+\epsilon+\epsilon^2)\leq \frac{|\alpha|(u_0+2)}{(u_0-\epsilon)^2}:=M.\end{equation*}Choose

$R \lt \frac{1}{M}$. Then

$R \lt \frac{1}{M}$. Then

\begin{equation*}\left| \int_0^s\frac{t}{s}g(t,u,u')\, dt\right|\leq \frac{Ms}{2}\leq \frac{MR}{2} \lt \frac{1}{2},\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}\left| \int_0^s\frac{t}{s}g(t,u,u')\, dt\right|\leq \frac{Ms}{2}\leq \frac{MR}{2} \lt \frac{1}{2},\end{equation*}so

$T$ is well-defined.

$T$ is well-defined.(ii) Prove the existence of

$\epsilon \gt 0$ such that

$\epsilon \gt 0$ such that  $ \mathsf{T}(\overline{\mathcal{B}(u_0,\epsilon)})\subset \overline{\mathcal{B}(u_0,\epsilon)}$. Choose

$ \mathsf{T}(\overline{\mathcal{B}(u_0,\epsilon)})\subset \overline{\mathcal{B}(u_0,\epsilon)}$. Choose  $R$ satisfying

(5.4)

$R$ satisfying

(5.4) \begin{equation}

R \lt \min\{\frac{1}{M},\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\epsilon,\frac{2 \epsilon}{M\sqrt{4+\epsilon^2}}\}.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

R \lt \min\{\frac{1}{M},\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\epsilon,\frac{2 \epsilon}{M\sqrt{4+\epsilon^2}}\}.

\end{equation}Since

$ f^{-1}$ is increasing,

$ f^{-1}$ is increasing,

\begin{equation*}

|( \mathsf{T} u)(r)-u_0|\leq \int_0^r f^{-1}\left(\int_0^s\frac{t}{s} M\, dt\right)\, ds

\leq \int_0^r f^{-1}\left(\frac{Ms}{2}\right)\, ds\leq \frac{R}{\sqrt{3}}.

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

|( \mathsf{T} u)(r)-u_0|\leq \int_0^r f^{-1}\left(\int_0^s\frac{t}{s} M\, dt\right)\, ds

\leq \int_0^r f^{-1}\left(\frac{Ms}{2}\right)\, ds\leq \frac{R}{\sqrt{3}}.

\end{equation*}By using (5.4), we have

$|( \mathsf{T} u)(r)-u_0|\leq \epsilon/2$. Thus

$|( \mathsf{T} u)(r)-u_0|\leq \epsilon/2$. Thus  $\| \mathsf{T} u-u_0\|_\infty\leq\frac{\epsilon}{2}$. Similarly, we have

$\| \mathsf{T} u-u_0\|_\infty\leq\frac{\epsilon}{2}$. Similarly, we have

\begin{equation*}

\begin{aligned}|( \mathsf{T} u)'-(u_0)'(r)|&\leq f^{-1}\left(\left|\int_0^r\frac{t}{r}g(t,u,u')\, dt\right|\right)\leq \left| f^{-1}\left(\frac{M}{2}r\right)\right|\\

&\leq \frac{MR}{\sqrt{4-M^2R^2}}\leq \frac{MR/2}{\sqrt{1-1/4}}=\frac{MR}{\sqrt{3}}\leq\frac{\epsilon}{2}

\end{aligned}

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\begin{aligned}|( \mathsf{T} u)'-(u_0)'(r)|&\leq f^{-1}\left(\left|\int_0^r\frac{t}{r}g(t,u,u')\, dt\right|\right)\leq \left| f^{-1}\left(\frac{M}{2}r\right)\right|\\

&\leq \frac{MR}{\sqrt{4-M^2R^2}}\leq \frac{MR/2}{\sqrt{1-1/4}}=\frac{MR}{\sqrt{3}}\leq\frac{\epsilon}{2}

\end{aligned}

\end{equation*}because (5.4) again. Then

$\|( \mathsf{T} u-u_0)'\|_\infty\leq \epsilon/2$. Definitively, we have proved

$\|( \mathsf{T} u-u_0)'\|_\infty\leq \epsilon/2$. Definitively, we have proved  $\| ( \mathsf{T} u-u_0)\|\leq \epsilon$.

$\| ( \mathsf{T} u-u_0)\|\leq \epsilon$.(iii)

$ \mathsf{T}\colon \overline{\mathcal{B}(u_0,\epsilon)}\to \overline{\mathcal{B}(u_0,\epsilon)}$ is a contraction. Let

$ \mathsf{T}\colon \overline{\mathcal{B}(u_0,\epsilon)}\to \overline{\mathcal{B}(u_0,\epsilon)}$ is a contraction. Let  $L_{f^{-1}}$ and

$L_{f^{-1}}$ and  $L_g$ be the Lipschitz constants of

$L_g$ be the Lipschitz constants of  $ f^{-1}$ and

$ f^{-1}$ and  $g$ in the domains above. For all

$g$ in the domains above. For all  $u,w\in C^1([0,R])$,

$u,w\in C^1([0,R])$,

\begin{equation*}\| \mathsf{T} u- \mathsf{T}w\|=\| \mathsf{T} u- \mathsf{T}w\|_\infty+\|( \mathsf{T} u)'-( \mathsf{T}w)'\|_\infty,\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}\| \mathsf{T} u- \mathsf{T}w\|=\| \mathsf{T} u- \mathsf{T}w\|_\infty+\|( \mathsf{T} u)'-( \mathsf{T}w)'\|_\infty,\end{equation*}Consider the first term

$\| \mathsf{T} u- \mathsf{T}w\|_\infty$. Given

$\| \mathsf{T} u- \mathsf{T}w\|_\infty$. Given  $u,w\in \overline{\mathcal{B}(u_0,\epsilon)}$ and

$u,w\in \overline{\mathcal{B}(u_0,\epsilon)}$ and  $r\in [0,R]$, we have

(5.5)

$r\in [0,R]$, we have

(5.5) \begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

|( \mathsf{T} u)(r)-( \mathsf{T}w)(r)|&\leq L_{f^{-1}} \left|\int_0^r \left(\int_0^r\frac{t}{s}(g(t,u,u')-g(t,w,w'))\, dt\right) \, ds\right|\\

& \leq L_{f^{-1}}L_g(\|u-w\|_\infty+\|u'-w'\|_\infty)\int_0^r(\int_0^s\frac{t}{s}\, dt)\, ds\\

&= L_{f^{-1}}L_g \frac{r^2}{4} \|u-w\| \leq L_{f^{-1}}L_g \frac{R^2}{4} \|u-w\| .

\end{aligned}

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

|( \mathsf{T} u)(r)-( \mathsf{T}w)(r)|&\leq L_{f^{-1}} \left|\int_0^r \left(\int_0^r\frac{t}{s}(g(t,u,u')-g(t,w,w'))\, dt\right) \, ds\right|\\

& \leq L_{f^{-1}}L_g(\|u-w\|_\infty+\|u'-w'\|_\infty)\int_0^r(\int_0^s\frac{t}{s}\, dt)\, ds\\

&= L_{f^{-1}}L_g \frac{r^2}{4} \|u-w\| \leq L_{f^{-1}}L_g \frac{R^2}{4} \|u-w\| .

\end{aligned}

\end{equation}For the term

$\|( \mathsf{T} u)'-( \mathsf{T}w)'\|_\infty$, the argument is similar. Indeed,

(5.6)

$\|( \mathsf{T} u)'-( \mathsf{T}w)'\|_\infty$, the argument is similar. Indeed,

(5.6) \begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

|( \mathsf{T} u)'(r)-( \mathsf{T}w)'(r)| &\leq \left| f^{-1}\left(\int_0^r \frac{t}{r}(g(u,u')-g(w,w'))\, dt\right)\right|\\

&\leq L_{f^{-1}}L_g \|u-w\| \int_0^r \frac{t}{r}\, dt= L_{f^{-1}}L_g \frac{r}{2} \|u-w\| \\

&\leq L_{f^{-1}}L_g \frac{R}{2}\|u-w\|.

\end{aligned}

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

|( \mathsf{T} u)'(r)-( \mathsf{T}w)'(r)| &\leq \left| f^{-1}\left(\int_0^r \frac{t}{r}(g(u,u')-g(w,w'))\, dt\right)\right|\\

&\leq L_{f^{-1}}L_g \|u-w\| \int_0^r \frac{t}{r}\, dt= L_{f^{-1}}L_g \frac{r}{2} \|u-w\| \\

&\leq L_{f^{-1}}L_g \frac{R}{2}\|u-w\|.

\end{aligned}

\end{equation}Let us change

$R$ by the condition (5.4) together with

$R$ by the condition (5.4) together with

\begin{equation*}R\leq \min\{\frac{1}{\sqrt{L_{f^{-1}}L_g}},\frac{1}{2L_{f^{-1}}L_g}\}.\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}R\leq \min\{\frac{1}{\sqrt{L_{f^{-1}}L_g}},\frac{1}{2L_{f^{-1}}L_g}\}.\end{equation*}Then we find from (5.5) and (5.6),

$\|\mathsf{T} u-\mathsf{T}w\|_\infty\leq\frac14\|u-w\|$ and

$\|\mathsf{T} u-\mathsf{T}w\|_\infty\leq\frac14\|u-w\|$ and  $\|(\mathsf{T} u)'-(\mathsf{T}w)'\|_\infty\leq\frac14\|u-w\|$, respectively. This gives

$\|(\mathsf{T} u)'-(\mathsf{T}w)'\|_\infty\leq\frac14\|u-w\|$, respectively. This gives

\begin{equation*}\| Tu-Tw\|\leq \frac12\|u-w\|.\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}\| Tu-Tw\|\leq \frac12\|u-w\|.\end{equation*}Thus

$\mathsf{T}$ is a contraction.

$\mathsf{T}$ is a contraction.

Finally, letting ![]() $r\to 0$ in (5.2) and applying L’Hôpital’s rule yields

$r\to 0$ in (5.2) and applying L’Hôpital’s rule yields

\begin{equation}

2u''(0)=\frac{\alpha}{u_0},

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

2u''(0)=\frac{\alpha}{u_0},

\end{equation} hence ![]() $u''(0)=\alpha/(2u_0)$.

$u''(0)=\alpha/(2u_0)$.

In Theorem 5.1, we established the existence of radial solutions ![]() $u$ of (5.3) in discs

$u$ of (5.3) in discs ![]() $B_R(0)\subset\mathbb R^2$ for sufficiently small

$B_R(0)\subset\mathbb R^2$ for sufficiently small ![]() $R$. At the same time, we proved regularity at

$R$. At the same time, we proved regularity at ![]() $r=0$ for solutions satisfying the orthogonality condition

$r=0$ for solutions satisfying the orthogonality condition ![]() $u'(0)=0$. In contrast, solutions of (5.3) with initial conditions at

$u'(0)=0$. In contrast, solutions of (5.3) with initial conditions at ![]() $r_0 \gt 0$ do not necessarily extend to

$r_0 \gt 0$ do not necessarily extend to ![]() $r=0$. This occurs, for instance, when

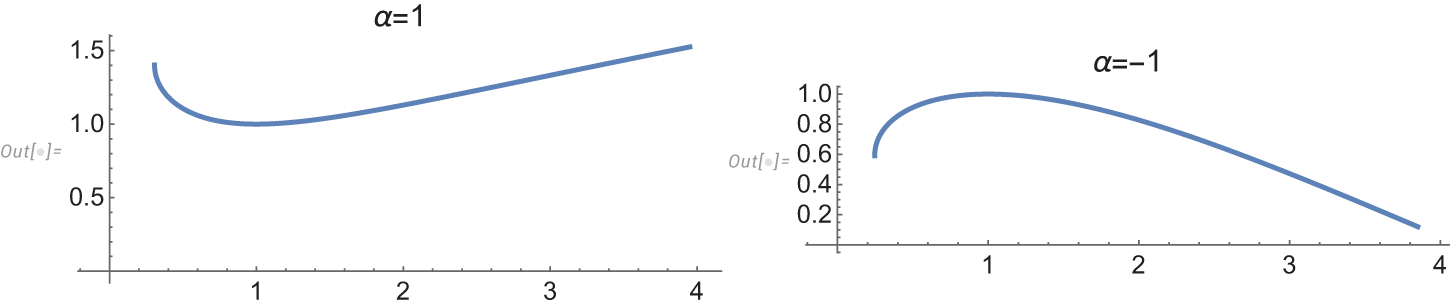

$r=0$. This occurs, for instance, when ![]() $\alpha \gt -2$. Figure 2 displays solutions of (5.3) with

$\alpha \gt -2$. Figure 2 displays solutions of (5.3) with ![]() $r_0=1$,

$r_0=1$, ![]() $u(1)=1$, and

$u(1)=1$, and ![]() $u'(1)=0$, which cannot be extended to

$u'(1)=0$, which cannot be extended to ![]() $r=0$.

$r=0$.

Figure 2. Two solutions of (5.3) that do not extend to ![]() $r=0$. The initial conditions are

$r=0$. The initial conditions are ![]() $r_0=u_0=1$ and

$r_0=u_0=1$ and ![]() $\alpha=1$ (left) and

$\alpha=1$ (left) and ![]() $\alpha=-1$ (right).

$\alpha=-1$ (right).

If a solution of (5.3) with ![]() $r_0 \gt 0$ can be extended to

$r_0 \gt 0$ can be extended to ![]() $r=0$, regularity at the origin is not automatic. In the next theorem, we address the issue of removable singularities for Eq. (1.2). We follow the general theory of mean curvature type equations. The classical example is the minimal surface equation, where isolated singularities are known to be removable [Reference Bers3, Reference Serrin22].

$r=0$, regularity at the origin is not automatic. In the next theorem, we address the issue of removable singularities for Eq. (1.2). We follow the general theory of mean curvature type equations. The classical example is the minimal surface equation, where isolated singularities are known to be removable [Reference Bers3, Reference Serrin22].

We write points of ![]() $\mathbb R^2$ as

$\mathbb R^2$ as ![]() $q=(x,y)\in\mathbb R^2$ and use

$q=(x,y)\in\mathbb R^2$ and use ![]() $(\cdot)$ for the Euclidean product of

$(\cdot)$ for the Euclidean product of ![]() $\mathbb R^2$. Equation (1.2) can be written in nonparametric form as

$\mathbb R^2$. Equation (1.2) can be written in nonparametric form as

\begin{equation}

\mbox{div}\left(\frac{Du}{\sqrt{1+|Du|^2}}\right)=\alpha\frac{u-(q\cdot Du)}{(x^2+u^2)\sqrt{1+|Du|^2}},

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\mbox{div}\left(\frac{Du}{\sqrt{1+|Du|^2}}\right)=\alpha\frac{u-(q\cdot Du)}{(x^2+u^2)\sqrt{1+|Du|^2}},

\end{equation} where the graph of ![]() $u=u(x,y)$ is an

$u=u(x,y)$ is an ![]() $\alpha$-stationary surface.

$\alpha$-stationary surface.

Theorem 5.2. Let ![]() $u$ be a

$u$ be a ![]() $C^2$-solution of (5.8) in a punctured disk

$C^2$-solution of (5.8) in a punctured disk ![]() $B_r(0)-\{0\}$, and assume that

$B_r(0)-\{0\}$, and assume that ![]() $u$ is Lipschitz continuous on

$u$ is Lipschitz continuous on ![]() $B_r(0)$. Then

$B_r(0)$. Then ![]() $u$ extends analytically to

$u$ extends analytically to ![]() $B_r(0)$.

$B_r(0)$.

Proof. We prove that ![]() $u$ is a weak Lipschitz solution of (5.8) on

$u$ is a weak Lipschitz solution of (5.8) on ![]() $B_r(0)$. Choose a sequence

$B_r(0)$. Choose a sequence ![]() $\{\eta_n\}\in C_c^\infty(B_r(0))$ such that:

$\{\eta_n\}\in C_c^\infty(B_r(0))$ such that:

(i)

$\mbox{supp}(\eta_n)\subset B_r(0)-\{0\}$, in particular,

$\mbox{supp}(\eta_n)\subset B_r(0)-\{0\}$, in particular,  $\eta_n= 0$ identically in a small neighbourhood around

$\eta_n= 0$ identically in a small neighbourhood around  $0$;

$0$;(ii)

$0\leq \eta_n\leq 1$ and

$0\leq \eta_n\leq 1$ and  $\eta_n\to 1$ a.e. in

$\eta_n\to 1$ a.e. in  $B_r(0)$;

$B_r(0)$;(iii)

$||D\eta_n||_{1,B_r}=\int_{B_r(0)}|D\eta_n|\, dxdy\to 0$ as

$||D\eta_n||_{1,B_r}=\int_{B_r(0)}|D\eta_n|\, dxdy\to 0$ as  $n\to\infty$.

$n\to\infty$.

Given any ![]() $\varphi\in C_c^\infty(B_r(0))$, set

$\varphi\in C_c^\infty(B_r(0))$, set ![]() $\phi_n=\varphi\eta_n$,

$\phi_n=\varphi\eta_n$, ![]() $n\in\mathbb{N}$. Then

$n\in\mathbb{N}$. Then ![]() $\phi_n\in C_c^\infty(B_r(0)-\{0\})$, and applying (5.8) gives

$\phi_n\in C_c^\infty(B_r(0)-\{0\})$, and applying (5.8) gives

\begin{equation}

\int_{B_r(0)}\frac{Du\cdot D\phi_n}{\sqrt{1+|Du|^2}}\, dxdy=\alpha\int_{B_r(0)}\frac{((q\cdot Du)-u)\phi_n}{(x^2+u^2)\sqrt{1+|Du|^2}}\, dx dy.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\int_{B_r(0)}\frac{Du\cdot D\phi_n}{\sqrt{1+|Du|^2}}\, dxdy=\alpha\int_{B_r(0)}\frac{((q\cdot Du)-u)\phi_n}{(x^2+u^2)\sqrt{1+|Du|^2}}\, dx dy.

\end{equation} Using ![]() $D\phi_n=\eta_nD\varphi+\varphi D\eta_n$, together with (5.9) and items (2) and (3), we obtain

$D\phi_n=\eta_nD\varphi+\varphi D\eta_n$, together with (5.9) and items (2) and (3), we obtain

\begin{equation*}\int_{B_r}\frac{Du\cdot D\varphi}{\sqrt{1+|Du|^2}}\, dx dy=\alpha\int_{B_r}\frac{(q\cdot Du)-u}{(x^2+u^2)\sqrt{1+|Du|^2}}\varphi\, dx dy.\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}\int_{B_r}\frac{Du\cdot D\varphi}{\sqrt{1+|Du|^2}}\, dx dy=\alpha\int_{B_r}\frac{(q\cdot Du)-u}{(x^2+u^2)\sqrt{1+|Du|^2}}\varphi\, dx dy.\end{equation*} Thus ![]() $u$ is a Lipschitz continuous solution of (5.8) which, in addition, is of class

$u$ is a Lipschitz continuous solution of (5.8) which, in addition, is of class ![]() $C^2$ on the punctured disc

$C^2$ on the punctured disc ![]() $B_r(0)-\{0\}$. Elliptic regularity then implies that

$B_r(0)-\{0\}$. Elliptic regularity then implies that ![]() $u\in C^2(B_r(0))$, and hence

$u\in C^2(B_r(0))$, and hence ![]() $u$ is analytic on

$u$ is analytic on ![]() $B_r(0)$.

$B_r(0)$.

As a consequence, if a radial solution ![]() $u$ of (5.1) extends to

$u$ of (5.1) extends to ![]() $r=0$ and meets the

$r=0$ and meets the ![]() $z$-axis non-tangentially, then it is analytic in the disk

$z$-axis non-tangentially, then it is analytic in the disk ![]() $B_{r_0}(0)$. Therefore, the intersection with the rotation axis must be orthogonal. If instead

$B_{r_0}(0)$. Therefore, the intersection with the rotation axis must be orthogonal. If instead ![]() $\gamma$ meets the axis tangentially, one can show that the corresponding rotational graph

$\gamma$ meets the axis tangentially, one can show that the corresponding rotational graph ![]() $u$ is still a weak solution of (5.8), belonging to

$u$ is still a weak solution of (5.8), belonging to ![]() $ C^2(B_r(0)-\{0\})\cap H_1^1(B_r(0))$ [Reference Dierkes6].

$ C^2(B_r(0)-\{0\})\cap H_1^1(B_r(0))$ [Reference Dierkes6].

6. Geometry properties of axisymmetric stationary surfaces

In this section, we classify the axisymmetric solutions of Eq. (1.2) that intersect the rotation axis orthogonally, and we describe their main geometric properties. Let the generating curve ![]() $\gamma$ of the surface be parametrized by arc-length,

$\gamma$ of the surface be parametrized by arc-length,

Using (5.1), the ODE system determining ![]() $\gamma$ is

$\gamma$ is

\begin{equation}\left\{

\begin{aligned}

x'(s)&=\cos\psi(s),\\

z'(s)&=\sin\psi(s),\\

\psi'(s) &= \alpha\frac{z(s)\cos\psi(s)-x(s)\sin\psi(s)}{x(s)^2+z(s)^2}-\frac{\sin\psi(s)}{x(s)}.

\end{aligned}

\right.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}\left\{

\begin{aligned}

x'(s)&=\cos\psi(s),\\

z'(s)&=\sin\psi(s),\\

\psi'(s) &= \alpha\frac{z(s)\cos\psi(s)-x(s)\sin\psi(s)}{x(s)^2+z(s)^2}-\frac{\sin\psi(s)}{x(s)}.

\end{aligned}

\right.

\end{equation} The initial conditions are ![]() $x(0)=0$ and

$x(0)=0$ and ![]() $\psi(0)=0$ (orthogonality to the axis). By Prop. 2.1, after an isometry we can assume

$\psi(0)=0$ (orthogonality to the axis). By Prop. 2.1, after an isometry we can assume ![]() $z(0) \gt 0$, and after a dilation, we set

$z(0) \gt 0$, and after a dilation, we set ![]() $z(0)=1$. Thus, we consider

$z(0)=1$. Thus, we consider

\begin{equation}

\left\{

\begin{aligned}

(x(0),z(0))&=(0,1),\\

\psi(0)&=0.

\end{aligned}

\right.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\left\{

\begin{aligned}

(x(0),z(0))&=(0,1),\\

\psi(0)&=0.

\end{aligned}

\right.

\end{equation} To analyze the phase portrait of an autonomous system, it is convenient to introduce the polar angle ![]() $\theta$ defined by

$\theta$ defined by

\begin{equation}

\tan\theta=\frac{z}{x}.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\tan\theta=\frac{z}{x}.

\end{equation}Using the first two equations of (6.1), we obtain

\begin{equation*}\theta'=\cos^2\theta\frac{\sin\psi-\tan\theta\cos\psi}{x}=\frac{\cos\theta}{x}\sin(\psi-\theta).\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}\theta'=\cos^2\theta\frac{\sin\psi-\tan\theta\cos\psi}{x}=\frac{\cos\theta}{x}\sin(\psi-\theta).\end{equation*}Similarly, the third equation in (6.1) becomes

\begin{equation*}

\psi' =

\alpha\frac{\tan\theta\cos\psi-\sin\psi}{x(1+\tan^2\theta)}-\frac{\sin\psi}{x}=-\frac{\alpha\cos\theta \sin(\psi-\theta)+\sin\psi}{x},

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\psi' =

\alpha\frac{\tan\theta\cos\psi-\sin\psi}{x(1+\tan^2\theta)}-\frac{\sin\psi}{x}=-\frac{\alpha\cos\theta \sin(\psi-\theta)+\sin\psi}{x},

\end{equation*}and hence

\begin{equation*}

\frac{d\psi}{d\theta}=\frac{\psi'(s)}{\theta'(s)}=- \frac{\alpha \cos \theta \sin(\psi-\theta) +\sin\psi}{\cos \theta \sin(\psi-\theta) }.

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\frac{d\psi}{d\theta}=\frac{\psi'(s)}{\theta'(s)}=- \frac{\alpha \cos \theta \sin(\psi-\theta) +\sin\psi}{\cos \theta \sin(\psi-\theta) }.

\end{equation*}This leads to the planar autonomous system

\begin{equation}

\left\{

\begin{aligned}

\frac{d\psi}{dt}&:=h_1(\psi,\theta)= -\sin\psi-\alpha \cos \theta \sin(\psi-\theta),\\

\frac{d\theta}{dt}&:=h_2(\psi,\theta)=\cos \theta \sin(\psi-\theta).

\end{aligned}

\right.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\left\{

\begin{aligned}

\frac{d\psi}{dt}&:=h_1(\psi,\theta)= -\sin\psi-\alpha \cos \theta \sin(\psi-\theta),\\

\frac{d\theta}{dt}&:=h_2(\psi,\theta)=\cos \theta \sin(\psi-\theta).

\end{aligned}

\right.

\end{equation} We study this system via Bendixson–Poincaré theory. From ![]() $h_2(\psi,\theta)=0$, the equilibrium points of (6.4) are