Introduction

Access to healthcare is a fundamental need for migrants, yet its essential nature can make it a tool for excluding certain groups or regulating migration flows. This article examines how access to healthcare functions as a form of internal bordering for EU migrants. Increasingly, migration governance has shifted from controlling entry at external borders to imposing restrictions within national territories, using social institutions to manage mobility (Yuval-Davis et al., Reference Yuval-Davis, Wemyss and Cassidy2018). In the UK, for example, the ‘hostile environment’ policy (Taylor, Reference Taylor2018) extends immigration checks into housing, healthcare, and employment, alongside increased detention and deportation. Within the National Health Service (NHS), patients must prove eligibility for free care – a key mechanism for deterring those without leave to remain. Such measures illustrate how welfare services are mobilised as tools of migration control.

Our analysis focuses on healthcare as a governance mechanism in three destination countries – Germany, Sweden, and the UK (pre-Brexit) – each representing a distinct welfare regime: Germany’s continental model, Sweden’s social-democratic model, and the UK’s liberal model. By comparing these contexts, we explore how healthcare access shapes the governance of EU migrants. While much research examines healthcare financing (Zelený and Bencko, Reference Zelený and Bencko2015), service provision (Mackintosh, Reference Mackintosh2016), or the experiences of diverse migrant populations (Phillimore et al., Reference Phillimore, Bradby, Knecht, Padilla and Pemberton2018), the role of healthcare in governing EU migrants remains underexplored. Existing studies often focus on undocumented migrants (Schweitzer, Reference Schweitzer2018), overlooking the barriers faced by EU citizens within the free mobility space.

Specifically, we examine the portability of social security – focusing on healthcare – across three transnational country pairs: Germany-Bulgaria, Sweden-Estonia, and the UK-Poland. We focus on EU mobile workers, who are central to both free movement rights and debates over welfare access. Our analysis draws on EU and national legislation, as well as sixty interviews with Central and Eastern European migrants (twenty per country). We present legal and policy frameworks in comparative tables, detailing available benefits and eligibility conditions.

Our article proceeds as follows: ‘Conceptual frame: bordering through (access to) healthcare’ provides an overview of previous research on healthcare and bordering. ‘Methodological frame’ outlines the research process and methodology. ‘Bordering through (access to) healthcare – a policy perspective’ presents our policy analysis, including empirical findings and the identification of regulatory ‘gateways’ that impose limitations on healthcare access for intra-EU migrants. ‘Intra-EU migrants’ explores experiences with accessing healthcare. Finally, we conclude with a discussion in which we argue that access to healthcare for EU migrants is shaped by different welfare state models.

Conceptual frame: Bordering through (access to) healthcare

States increasingly outsource internal borders to institutions, empowering private and local actors (Yuval-Davis, Reference Yuval-Davis2016). These re-bordering processes (Yuval-Davis et al., Reference Yuval-Davis, Wemyss and Cassidy2018) challenge the idea of borders as fixed territorial lines (Scott, Reference Scott2011), shifting migration control from external frontiers to internal governance embedded in specific political contexts. A central mechanism in this shift is the governance of deservingness – deciding which migrants merit access to rights, and under what conditions (Dahlstedt and Neergard, Reference Dahlstedt and Neergard2019; Ratzmann and Sahraoui, Reference Ratzmann and Sahraoui2021). Debates on migrant deservingness reveal how access to rights is shaped by political discourses on belonging: only those meeting state-defined duties are seen to ‘belong’. These notions underpin new exclusionary borders drawn around social rights and welfare access. Negative public perceptions of migration (Blinder, Reference Blinder2011) feed into policy debates on fairness, often serving as justification for restricting benefits to certain migrant groups (Carmel and Sojka, Reference Carmel and Sojka2021). We have suggested elsewhere (Sojka and Saar, Reference Sojka, Saar, Rees, Heins and Pomati2020) that there is a link between welfare state models suggested by Esping-Anderssen (Reference Esping-Andersen1990) and different discourses on migrant deservingness. We proposed that the normative foundations embedded in different welfare systems lead to dissimilar ways of discursive approach to migrants and migration, which lead as to our research question on how bordering is organised through governance of immigrants’ access to welfare taking access to healthcare as an example. This claim is very much connected to the idea that welfare state models impact how fairness and justice are being perceived and therefore also influence how migrants ought to be included in the welfare system. Such perceptions, however, apply not only to migrants but to the wider population. Welfare state bordering, as introduced by recent scholarship (see Guentner et al., Reference Guentner, Lukes, Stanton, Vollmer and Wilding2016; Bendixsen and Näre, Reference Bendixsen and Näre2024), deepens this discussion by examining how European nation-states manage and control migration through welfare state policies, services, and practices. Welfare state bordering refers to the practices of controlling and managing access to social rights based on residence, migrancy, and citizenship within a socio-political order. This concept complements the idea of internal borders by showing how welfare policies are not just safety nets but also tools of migration control. Through welfare state bordering, national and local governments, along with street-level bureaucrats (Lipsky, Reference Lipsky1980), act as gatekeepers, managing migrants’ access to rights and services, thus contributing to social exclusion, for example in Nordic countries (Barker Reference Barker2017; Könönen Reference Könönen2018; Näre et al., Reference Näre, Bendixsen and Maury2024) or Southern European countries (Perna, 2018, Reference Perna2019) There is a growing body of research on healthcare and bordering in U.S. scholarship, with scholars like Van Natta (Reference Van Natta2023) highlighting how healthcare is increasingly used as a bordering mechanism. These studies show how anti-immigrant laws create barriers to healthcare, intertwining legal status with access, which results in systemic exclusion and mistrust in immigrant communities (Parmet, Reference Parmet2019; Gómez Cervantes and Menjívar, Reference Gómez Cervantes and Menjívar2020). In Europe, Bendixsen (Reference Bendixsen2019) notes how irregular migrants in Norway experience ‘intimate borders’ in healthcare, where legal status determines access to services, and healthcare workers often view migrants with suspicion. Guentner et al. (Reference Guentner, Lukes, Stanton, Vollmer and Wilding2016) describe how healthcare systems act as sites of welfare bordering, where access is regulated by legal and economic criteria, excluding marginalised groups. Policies like the UK’s ‘No Recourse to Public Funds’ rule and charges for non-residents further demonstrate how healthcare is transformed from a universal right into a selective privilege. Schweitzer (Reference Schweitzer2018) highlights how administrative barriers and professional discretion in London and Barcelona shape access to healthcare for irregular migrants, reinforcing exclusion even where formal entitlements exist.

The article utilises Esping-Andersen’s (Reference Esping-Andersen1990) welfare state models to examine how bordering practices in the healthcare sector shape access for EU migrants. The UK exemplifies the liberal model, characterised by minimal state intervention and market-oriented solutions, which, while facilitating initial access, often result in inequalities and gaps in comprehensive support. However, there are differences in how secondary healthcare is provided in England and Scotland that stem primarily from the structure and delivery mechanisms of healthcare, reflecting both historical and political choices made by each country within the UK. Esping-Andersen’s (Reference Esping-Andersen1990) welfare typology categorises welfare states into liberal, corporatist, and social democratic regimes. The UK is generally placed within the liberal model, characterised by limited state involvement, a reliance on means-tested benefits, and a significant role for the private sector. While the NHS offers universal healthcare funded through taxation, the broader UK welfare system emphasises targeted support over universal provision, and private providers play an increasing role, particularly in secondary care.

Germany represents the corporatist model, where benefits are closely tied to employment and contributions, fostering stability but creating barriers for those with fragmented work histories. Sweden illustrates the social-democratic model, emphasising universal access and egalitarian principles, yet relying on administrative requirements like residency verification, which can inadvertently exclude mobile and precariously situated populations.

The article draws on Phillimore et al.’s (Reference Phillimore, Bradby, Knecht, Padilla and Pemberton2018) concept of healthcare bricolage, which refers to the strategies migrants use to navigate complex healthcare systems by leveraging resources across borders. Faced with barriers, migrants combine knowledge, networks, and transnational ties to access care – such as maintaining home country insurance, relying on informal networks, or seeking affordable treatment abroad. In our case, healthcare bricolage helps explain how EU migrants navigate disparities in healthcare across different welfare models within the EU.

Methodological frame

This material is drawn from data collected during the TRANSWEL (Mobile Welfare in a Transnational Europe) project, which examined mobile EU citizens’ access to and portability of social security rights in four pairs of European countries: Hungary-Austria, Bulgaria-Germany, Poland-United Kingdom and Estonia-Sweden. However, in this article we omit Hungary-Austria as a case study because we consider the patterns found in the case to be quite comparable to Bulgaria-Germany case, mostly due to the similarities in the welfare systems between Germany and Austria.

The empirical research on the three transnational cases, and six sets of national social security regulations, included: (1) documentary analysis; (2) key informant and policy expert interviews; and (3) interviews with immigrants themselves. The analytical framework, methodology, and methods for the TRANSWEL project were designed by four research teams (see acknowledgements) to explore portability of and access to four types of social security rights (unemployment, healthcare, pension, and family benefits). In this article we show how EU mobile citizens access to healthcare is used as means of bordering within EU.

Policy analysis, key informant, and policy expert interviews

For the policy analysis, we compared statuatory sick pay (SSP) regulations across thirty-four country-pair cases, focusing on how welfare system conditionalities organise and limit access to social security benefits. We used an inductive, transnational, and comparative research design, considering both ‘sending’ and ‘receiving’ country perspectives. The analysis explored how SSP regulations create opportunities for inclusion and exclusion of EU mobile citizens in accessing healthcare. In addition to documentary analysis, we conducted sixteen key informant interviews (welfare rights workers, lawyers, and practitioners) and twenty-eight interviews with senior policy experts (ministry officials, policy advisors, and legal experts) across three EU country pairs. These interviews clarified eligibility criteria and provided insights into EU social security regulation for free movers. The data was analysed using Interpretive Policy Analysis (IPA), situating regulations within expert subjectivity and broader socio-political contexts (Yanow and Schwartz-Shea, Reference Yanow and Schwartz-Shea2015).

Interviews with immigrants

Following the policy analysis and expert interviews, we conducted eighty interviews with migrants living in destination countries. Our methodology was informed by constructivist Grounded Theory (Charmaz, Reference Charmaz2006), with data collection and analysis occurring simultaneously to guide theory development. Interviews took place between December 2015 and April 2017, facilitated by local NGOs, Saturday schools, churches, and researchers, and were conducted in Estonian, Bulgarian, and Polish. Each of the three research teams produced detailed reports on case studies, focusing on access and portability of social security rights, barriers, inequality experiences, and transnational coping strategies across four policy areas: unemployment, family benefits, health, and pensions. For this article, we focus on healthcare, analysing how access functions as a form of bordering within the EU. We begin with policy-level bordering, followed by how EU mobile citizens experience it in practice.

Bordering through (access to) healthcare – policy perspective

Intra-EU migrants’ access to healthcare – EU perspective

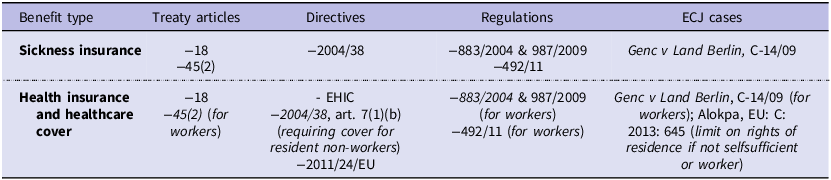

There are many aspects to consider regarding the strategies that are employed in bordering through healthcare. In this article, we focus on intra-EU migrants whose access to social services in other member states is often perceived as unproblematic (La Fleur and Mescoli, Reference La Fleur and Mescoli2019). Although the EU provides common rules to protect social security rights of intra-EU migrants, access to social security is complex and shaped by regulations that generate rights that vary according to welfare state, policy area, and individual migration history (Carmel et al., Reference Carmel, Sojka, Papież, Amelina, Carmel, Runfors and Scheibelhofer2019). This includes complex coordination of healthcare (Table 1) that encompasses treaty articles; directives, regulations, and European Court of Justice (ECJ) cases.

Table 1. Key relevant sources of legal regulation in the European Union affecting portability and access to healthcare for intra-EU migrants (Carmel et al. Reference Carmel, Sojka and Papiez2016)

Source: Carmel et al. 2015.

Directive 2011/24/EU on the application of patients’ rights in cross-border healthcare enables patients to secure treatment in another member state. Intra-EU migrants who take up ‘genuine and effective’ employment is considered to be a worker. Employed or self-employed workers can move within EU member states and are entitled to equal treatment with nationals in employment and access to social benefits after the first three months, including access to healthcare. However, member states define what is ‘genuine and effective’ employment in their domestic legislation, which allows room for internal bordering within particular member states. For example, some member states tighten their definition excluding various types of employees from accessing socials security (Carmel and Paul, Reference Carmel and Paul2013; O’Brien et al., Reference O’Brien, Spaventa and De Coninck2016); others decide to deport EU movers who have temporarily fallen dependent on welfare (La Fleur and Mescoli, Reference La Fleur and Mescoli2019). The following section focuses on various bordering practices in healthcare policy and is based on our policy analysis and key informant and policy expert interviews (see section on methodological frame).

Intra-EU migrants’ access to healthcare in three country pairs: Bulgaria-Germany; Estonia-Sweden, and Poland-UK policy analysis

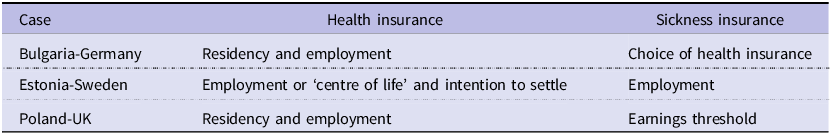

Our research shows that the combination of EU legislation and our transnational country pair regulations on healthcare insurance are straightforward in relation to the European Health Insurance Card (EHIC) as the card was designed exclusively for emergency health treatments and thus does not cover access to healthcare as such. EHIC is also time-limited and can be used only for the three initial months period, past which an EU mobile citizen need to gain additional access to healthcare. More generally, we found various key regulatory conditions governing portability of health insurance and healthcare in three EU transnational country-pairs (Table 2).

Table 2. Health and sickness insurance by country pair

Country pair analysis: welfare state models in action

Our analysis of three transnational country pairs – Bulgaria-Germany (BG/GE), Estonia-Sweden (EE/SE), and Poland-UK (PL/UK) – illustrates how welfare state models shape healthcare access and bordering practices (Table 1). These pairs reflect diverse welfare state approaches, including corporatist (Germany), social democratic (Sweden), and liberal (UK) systems, each imposing distinct procedural and regulatory conditions.

Health insurance

In corporatist systems like Germany, health insurance is closely tied to employment. Access is immediate upon employment, but returnees must meet contribution requirements in their home countries to continue coverage. This creates barriers for circular or temporary migrants who lack consistent employment histories.

In social democratic systems like Sweden, healthcare is accessible to insured workers without a Swedish personal identity number (PIN), provided they have a certificate of residence. However, mobile citizens with precarious employmentFootnote 1 must demonstrate an intention to settle and secure a PIN, which acts as an administrative border. By contrast, Estonia requires private insurance for unemployed returnees, reflecting a more restrictive approach.

In liberal systems like the UK, healthcare is residency-based, with minimal procedural barriers. While this system appears more inclusive, it may offer less comprehensive protection compared to insurance-based systems, particularly for migrants returning to countries like Poland, where health coverage often requires insurance contributions or registration as unemployed.

Sickness insurance

Sickness insurance, closely tied to employment and insurance contributions, illustrates how welfare state models create varied bordering practices across member states. Despite EU-wide regulations aiming to harmonise social security systems, national policies introduce significant divergences, shaping the experiences of intra-EU migrants.

In Germany, a corporatist welfare state, sickness insurance is employment-based and applies from the first day of employment. Workers can choose their type of sickness insurance, reflecting a system designed for labor market stability and individual autonomy. However, for returnees to Bulgaria, a key challenge arises: insurance portability. Migrants must demonstrate at least six months of prior contributions, either in Bulgaria or another member state, to access health benefits. This requirement highlights the administrative barriers faced by mobile citizens who lack continuous employment histories.

The Estonia-Sweden case reveals how social democratic welfare systems, like Sweden’s, attempt to balance inclusivity with administrative controls. Sweden allows individuals to accumulate insured periods from other EU member states, facilitating transnational coverage. However, this inclusivity is conditioned by a requirement for migrants to express an intention to settle for at least one year. For mobile citizens without prior employment, this intention must be formalised, emphasising long-term integration over temporary mobility. This procedural condition serves as a form of internal bordering, restricting access for more precarious or transient migrants.

In contrast the UK’s liberal welfare model uses residency for sickness insurance. This residency-based approach lowers barriers for intra-EU migrants compared to insurance-based systems, as eligibility does not require an employment contract or prior contributions. However, this flexibility comes with its own procedural requirements. Migrants must provide proof of residency, which can act as an internal border for those with precarious housing or highly mobile lifestyles. Returnees from the UK to Poland face significant challenges in re-establishing sickness insurance coverage, a process shaped by the contrasting welfare state models of these two countries. For returnees to Poland, the absence of insurance contributions during their time in the UK can create barriers to accessing healthcare. Returnees must either secure an employment contract or register as unemployed to qualify for sickness insurance.

Conclusions from policy analysis

The regulation of healthcare access for intra-EU migrants varies significantly depending on the welfare state model of the host country, leading to different forms of internal bordering. In Germany, a continental welfare state, access to healthcare is closely tied to employment and residency, with a complex system of insurance that requires continuous contributions, making it difficult for migrants with precarious or short-term employment to maintain coverage. Sweden, as a social democratic state, offers universal healthcare, but access is contingent on fulfilling stringent procedural requirements such as obtaining a PIN and proving an intention to settle. This creates high entry barriers for mobile or temporary migrants. In contrast, the UK, a liberal welfare state, bases healthcare access primarily on residency rather than employment, providing a more straightforward pathway for migrants. However, the simplicity of access in the UK is offset by minimal procedural requirements, which may not fully address the needs of more vulnerable migrant populations.

Furthermore, the analysis of EU mobility between different welfare state models offers additional insights into welfare state bordering. In corporatist systems like Germany and Poland, healthcare access depends on employment and contributions, leaving returnees from less rigid systems, such as the UK, to navigate procedural hurdles to regain coverage. Social democratic systems like Sweden facilitate portability through mechanisms like the accumulation of insured periods but impose administrative barriers, such as securing a PIN or proving an intention to settle, which exclude precarious or mobile workers. Liberal systems like the UK lower entry barriers with residency-based access but often leave migrants unprepared for the contribution requirements of corporatist systems upon return.

These disparities show how welfare state traditions mediate the transferability of healthcare rights, creating vulnerabilities for mobile citizens and returnees. Despite EU regulations, national policies remain fragmented.

Intra-EU migrants’ experiences with accessing healthcare

In the previous section, we compared how regulatory conditions in each country pair shape healthcare access for first-time and returning migrants, drawing on Carmel et al. (Reference Carmel, Sojka and Papiez2016). While intra-EU migrants’ legal entitlements often appear straightforward, entitlement does not guarantee use (Mladovsky et al., Reference Mladovsky, Rechel, Ingleby and McKee2011). In practice, access depends on overcoming personal, financial, and organisational barriers Gulliford, (Reference Gulliford, Figueroa-Munoz, Morgan, Hughes, Gibson, Beech and Hudson2002). Personal barriers include perceptions of need, beliefs, and past experiences with providers; financial barriers involve costs of care; and organisational barriers reflect procedural and referral practices. For migrants, these challenges are compounded by legal status and differences between origin and destination healthcare systems. The following section examines such experiences in Sweden, the UK, and Germany.

Estonians in Sweden

Sweden’s regulatory framework, with its complex and bureaucratic system, is difficult for migrants to navigate. The Swedish PIN system acts as a barrier to access and portability, as it’s required for most benefits and registration with Swedish authorities. Obtaining a PIN requires proof of employment and residency for over a year, which is challenging for EU migrants in short-term or temporary jobs. Unemployed or irregularly employed migrants without formal employment in Sweden are excluded from the PIN system and must show comprehensive health insurance, either state or private. Waiting times for PINs can be several months (Saar and Sojka, Reference Sojka, Saar, Rees, Heins and Pomati2020) (see also Carmel and Cerami, Reference Carmel and Cerami2012). Before 2015, the threshold for ‘comprehensive health insurance’ was particularly high for those without formal employment.

Raivo case shows how accessing healthcare in Sweden is problematised through provision of PIN. He is a 46-year-old Estonian male construction worker who has lived in Sweden since 2002.

Raivo worked informally for sixteen years, but his current employment is legal. During his informal work period, he registered as an employee in an Estonian company and paid social insurance taxes in Estonia, granting him access to the Estonian healthcare system. When he started formal work in Sweden, he applied for a Swedish PIN, but it was denied because his ‘centre of life’ was in Estonia, where he paid taxes and his family lived. As a result, he never received a PIN and continues to use a temporary samordningsnummer for short-term workers in Sweden. He explains that the lack of a PIN has caused significant challenges, including difficulty accessing healthcare.

One cannot enter the system with temporary PIN when you go to a doctor. It is always a hassle. On the other hand, it works with the Tax Office. But once I wanted to have a phone contract in the shop and they wanted a PIN. So, I thought, I should maybe get this going…. (Raivo, age 46, Estonia).

Lack of a PIN forced Raivo to access the Swedish healthcare system via the EHIC. This, however, is difficult because obtaining an EHIC is a lengthy process (as he would have to apply for one in Estonia, but since he is working in Sweden Estonia as well might refuse to hand out EHIC) and accessing healthcare using EHIC is not a straightforward procedure and is relevant for treatments that are urgent.

Confusion over the Swedish welfare system and especially over provision of a PIN made Raivo lose his trust in the system as well as his abilities to access his rights:

Healthcare is also…. You call them …We had a problem here. One guy’s EHIC expired. First you do not get hold of them. Secretary sat I think for three days trying. And finally, she got hold of them. They had some problem; the papers were just lying around. One employee left for pregnancy leave. The other employee came but never looked. So, these papers were just lying (Raivo, age 46, Estonia).

Even though Raivo started to work legally, his situation did not change and he still did not obtain a PIN number. According to him Swedish authorities are insufficient and careless. Also, his knowledge of his legal situation is somewhat limited as he explains that his current employer deals with his legal status. Raivo’s case is not unique as several of interviewees shared their confusion over Swedish welfare system and especially the ways in which PINs are obtained. To cope with lack of a PIN Estonian immigrants in Sweden often insure themselves back in Estonia, which gives them access to healthcare in their country of origin.

Consequently, our interviews with Estonian immigrants in Sweden correspond with our policy analysis in which we showed that mobile citizens with more precarious employment and higher levels of mobility may encounter issues with accessing healthcare due to lack of ability to securing their PIN. Thus, the PIN is a pre-cursor to the generation of entitlements or lack thereof.

Bulgarians in Germany

As our policy analysis shown German regulations and collaboration between the two countries make the portability of benefits relatively straightforward. This is especially true for long-term and employed immigrants. However, for short-term immigrants with a fragmented history of employment, accessing healthcare pose a challenge. Portability of health insurance is highly specified in formal regulations, but the health insurance market is complex. Expert interviews emphasised that many mobile Bulgarian citizens do not have health insurance coverage in either country, creating difficulties for Bulgarians in need of healthcare in Germany.

Exploring interviews with Bulgarian immigrants living in Germany showed that accessing healthcare insurance is problematic. For instance, Vania is a 47-year-old woman who supports her ill mother and sons who stayed in Bulgaria. She works in a restaurant and is unaware whether her employer pays her contributions to pension and unemployment fund. In terms of health insurance, she chooses to pay for it in both Germany and Bulgaria. She explains why:

For me, it is easier to pay in this money there until I am there and in case I will need, if I only have the necessity. To be able to go without a problem (Vania, age 47, Bulgaria).

Vania is unaware of how German health insurance fund works. She gathers information from rather random sources and, for example, one was told that if she will use her E104Footnote 2 in Bulgaria her insurance in Germany will be cased, which is incorrect. As a result of complex healthcare insurance system in Germany and misinformation she decided to pay healthcare insurance in both countries.

Also, she does not have a general practitioner (GP) in Germany mainly due to lack of language proficiency and additional cultural barriers such as communicating about her health problems via phone call with healthcare providers and long waiting periods:

I feel very uncertain with this phone calling for the results […] and if you receive an appointment to the doctor in a month, I think it is not right; so many things can happen for a month (Vania, age 47, Bulgaria).

Other interviewees shared similar issues surroundings accessing healthcare in Germany. In general, the German healthcare system is perceived as very difficult to navigate. Immigrants, especially those in low pay and irregular employment and/or with lack of language proficiency, exposed lack of awareness and planning in relation to their healthcare insurance in Germany. This is not surprising as our policy analysis showed that health insurance is accessed with employment with portability regulations being strongly regulated and the health insurance market complex. Additionally, interviewed expert highlighted that many mobile Bulgarian citizens do not have health insurance coverage in either country.

Polish in the UK

Recent reforms in the UK have made decision-making processes more opaque, complicating matters for migrants trying to understand their rights and for decision-makers interpreting regulations and exercising discretion. Changes to residency and procedural requirements create significant barriers for EU migrants seeking unemployment and family benefits. Revisions to guidelines on what constitutes ‘genuine and effective work’ and a ‘genuine prospect of work’ may further hinder EU migrants’ access to and portability of social security rights. These measures especially disadvantage more mobile and more precariously employed migrant workers. The high levels of discretion accorded to decision-makers enhances uncertainty for migrants. However, our policy analysis showed that access to healthcare is straightforward as the British NHS has limited mechanisms for generating barriers to access, and portability does not apply due to its tax-based funding. Surprisingly, interviews painted another picture insofar that although Polish immigrants have a straightforward access to healthcare, their experiences of it are unsatisfactory thus they choose alternative ways for accessing healthcare.

Darek is 43 years old, male, who works as a bus driver. He lives and works in the UK while his wife and children live in Poland. He has several health problems such as issues with his heart and high blood pressure, therefore he needs to be under regular doctor’s surveillance. Darek, as an employed Polish immigrant, has a right to access the NHS. However, his experiences accessing it in practice are complicated. For example, Darek perceives GPs working in the NHS lacking in medical knowledge and regards treatment and healthcare service in the UK poorly:

The GPs here do not know anything, they check information on the Internet e.g. google.co.uk […] They [doctors at the hospital] gave me pills, and they said that I should relax. (…) they should give me drip-bag not a pill. But I feel that is worse and worse with my health. (…). Later I talked with my GP, and he confirmed that should receive treatment which works quicker than pills. So, how to trust them [doctors in the UK]? (Darek, age 43, Poland).

Darek’s perception of the NHS are example of sociocultural barriers to healthcare care at what Betancourt et al. (Reference Betancourt, Green, Carrillo and Ananeh-Firempong2003) refers to as clinical provider-patient encounter – level. For him, doctors lack of medical knowledge and medical training (Osipovič, Reference Osipovič2013):

But here [in the UK] the GP discourages me to take any medicines […] Antibiotic…? In pharmacy when they see prescriptions for antibiotic, they double check with me if I am aware that this is an antibiotic. It is unusual for them to use antibiotics. They wanted to change antibiotic for me because they were afraid that I can be addicted to antibiotic. They ask so many questions, they treat you as a fool. Not necessary me, but I know that they treat people as fools (Darek, age 43, Poland).

This negative perception of medical practices was shared among most of the interviewees and was reported by other research on Polish immigrants’ access to healthcare in the UK (Osipovič, Reference Osipovič2013). Also, expectation of availability of antibiotic is linked with a culture of healthcare practice in the immigrants’ country of origin (Collis et al., Reference Collis, Stott, Ross and Salisbury2012; Duckworth et al., Reference Duckworth, Wykes and Priebe2012).

Immigrants’ healthcare-seeking behaviours are complex, and immigrants use ‘healthcare bricolage’ as a tactic where immigrants creatively use their resources to access healthcare (Phillimore et al., Reference Phillimore, Bradby, Knecht, Padilla and Pemberton2018). This tactic includes seeking access to healthcare transitionally. Sojka et al. (Reference Sojka, Carmel, Papiez, Amelina, Carmel, Runfors and Scheibelhofer2019) highlight the importance of transnational healthcare practices that Polish immigrants are engage with in the UK. The concept of healthcare bricolage, introduced by Phillimore et al. (Reference Phillimore, Bradby, Knecht, Padilla and Pemberton2018), refers to the creative and adaptive strategies that individuals, particularly migrants in superdiverse urban areas, use to navigate and access healthcare services. This approach involves the mobilisation and recombination of various resources, such as knowledge, networks, and materials, to meet health needs in situations where formal healthcare systems may be inaccessible, unfamiliar, or insufficient. For instance, Darek, despite having access to healthcare providers in the UK, continues to use healthcare providers in Poland:

In our [country] GP has authority, right? I have my own GP [in Poland], who is my very good friend. […] The GP [in the UK] is a backup for me. I use health service in Poland. […] I use private healthcare in Poland. I go to my good friend. He [GP in Poland] is available for me every time. I can call him, and I can talk to him every time when I need (Darek, age 43, Poland).

Darek illustrates how some immigrants navigate complex healthcare systems with ease. Although entitled to care in the UK, he chooses to access healthcare transnationally. Research on culturally and linguistically diverse communities highlights the importance of awareness and choice in healthcare access – awareness of available services and choices based on factors like proximity and language (Garg et al., Reference Garg, Sheppard and Dawson2017). Similarly, most Polish immigrants in our study preferred to access healthcare in Poland.

Conclusions from interviews with migrants

We have here used single migrant stories to illustrate hurdles which migrants went through in accessing healthcare; in each case, however, they do represent patterns which we found in our data.

Migrants in Sweden often struggled to access healthcare when they had not obtained a PIN. Theoretically access is possible with only samordningsnummer (given to all people who pay tax in Sweden), but in practice it proved to be extremely difficult to gain access because many healthcare providers had no knowledge of ‘samordningsnummer’ nor did they want to process those with no PIN. Sweden thus paradoxically excludes many mobile and precariously employed EU migrants through its reliance on the PIN. The bureaucratic complexity of obtaining a PIN, as seen in Raivo’s case, highlights how procedural requirements can undermine inclusivity, pushing migrants to rely on transnational strategies like insuring themselves in their home country.

Germany’s corporatist model, rooted in employment-based insurance, creates significant challenges for migrants with fragmented work histories. Bulgarian migrants, such as Vania, often pay into multiple insurance systems or remain uninsured due to misinformation and the complexity of the system. The strategy of keeping multiple health insurances was not singular but rather common, and Bulgarian migrants in Germany generally showed a highly levels of anxiety but also confusion when it came to accessing benefits, also healthcare access. The reliance on employment and contributions in German system reinforces stability for those securely employed but excludes vulnerable groups, emphasising the systemic rigidity of corporatist welfare states.

In the UK, the liberal model offers broad access through a residency-based system, but cultural and systemic barriers diminish trust in the quality of care. Polish migrants like Darek, dissatisfied with treatment standards, frequently seek healthcare in their home country, revealing the model’s lack of tailored services for diverse populations. While flexible in granting access, the UK system often fails to address the nuanced needs of mobile citizens. The dissatisfaction with NHS among Polish citizens in UK was relatively common and again illustrates differences between welfare systems. The Polish corporatist model offers much more extensive care and easier access for those who are insured, whereas NHS offers basic healthcare access, but its capabilities as perceived by Polish migrants are rather limited.

Discussion

This study highlights how welfare state models shape the inclusion and exclusion of EU migrants through healthcare, creating internal borders that regulate mobility within the EU’s free movement framework. The findings reveal significant disparities across liberal, corporatist, and social-democratic models.

Germany’s contributory welfare system ties healthcare access to employment and residency, creating barriers for migrants in precarious work or without stable employment. The system’s complexity effectively excludes those who cannot meet these requirements.

In Sweden, despite a commitment to universal coverage, migrants face exclusion due to residency requirements and bureaucratic hurdles, like the need for a PIN. This creates internal borders, revealing the gap between the system’s ideals and its operational realities.

The UK offers broader access through a tax-funded, residency-based system but lacks tailored services for vulnerable migrants, leading to indirect barriers for those with complex needs. This paradox illustrates how a system that seems inclusive can still exclude certain migrant groups.

These findings demonstrate how welfare systems shape the portability of healthcare rights, posing challenges to the EU’s free-mobility principle. Migrants from employment-based systems like Germany and Poland face barriers when returning to more flexible systems, like the UK, highlighting the rigidity of contribution-based frameworks.

Migrants’ reliance on ‘healthcare bricolage’ – seeking healthcare outside national systems – exposes the deeper systemic issues in these welfare models. In Germany, bureaucratic complexity marginalises migrants with unstable employment. In Sweden, residency status and administrative barriers make healthcare practically inaccessible for transient migrants. In the UK, a lack of tailored services leads to dissatisfaction, with migrants often seeking cross-border healthcare in their home countries. These strategies reveal the systemic failures of welfare state models to support mobility and undermine the EU’s vision of free movement and equitable inclusion.

This study examines how welfare state models act as mechanisms of internal bordering, regulating healthcare access and shaping the mobility and inclusion of EU migrants. By comparing the UK, Germany, and Sweden, it highlights how healthcare systems reflect deeper norms around deservingness, integration, and mobility. These systems turn healthcare from a universal right into a selective privilege, based on migrants’ ability to navigate bureaucratic and economic barriers. This internal bordering undermines the EU’s commitment to free movement and universal inclusion, revealing tensions between transnational ideals and national welfare frameworks. Migrants’ reliance on ‘healthcare bricolage’ exposes these systems’ inadequacies, signalling the need for welfare models that transcend national boundaries to promote equitable access across Europe.

Author Contributions: CRediT Taxonomy

Bozena Sojka: CRediT contribution not specified.

Maarja Saar: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology.

Appendix 1

The intention to settle for intra-EU movers refers to the act of an individual planning or intending to establish long-term residence in a country within the European Union. While the concept may vary slightly depending on context or legal framework, here are some common interpretations and definitions:

-

1. Legal Definition: In the context of EU law, intention to settle often refers to a migrant’s intent to reside in an EU country for a prolonged or indefinite period. This could be relevant for obtaining certain residency rights, social benefits, or access to public services. For example, the EU Freedom of Movement directive grants EU citizens the right to reside and work in other member states, but this right may evolve into more permanent residency status after a certain period (typically five years), often influenced by whether the individual can demonstrate an intention to settle.

-

2. Social and Practical Implication: The intention to settle also involves subjective factors such as integration into the local community, long-term employment, housing arrangements, or family ties. It can be assessed by authorities based on these indicators, such as securing a job contract, signing a long-term lease, or enrolling children in local schools.

-

3. Administrative or Formal Process: In some cases, countries might require documentation to formalise the intention to settle. This could include registering with local authorities or applying for long-term residence permits. This legal process helps distinguish between short-term mobility for work or study and the decision to become a long-term resident.

-

4. In the Context of Welfare and Social Rights: The formalisation of intention to settle can also have implications for access to certain social welfare benefits. In many countries, welfare access is tied to the length of time a person has lived in the country and their residency status. Therefore, showing an intention to settle could be necessary for migrants to access full benefits or health services after a certain period.

In summary, the intention to settle for intra-EU movers involves both legal criteria (e.g., registration, residence status) and social factors (e.g., long-term plans for employment and community integration), and it plays a key role in determining eligibility for various rights, including social benefits and healthcare.