A truly democratic city must empower its citizens and institutions as agents of change, through collective decision-making focused towards the common good. In order to achieve this, an urban pedagogy is necessary, aimed at encouraging collective decisions that include emotions and the advocacy of territorial governance; thus each citizen, along with institutions, in independent or organized fashion, exercise their capacity to self-govern.

This pedagogy would allow for citizens, schools, and universities, among others, to reactivate their social role, multiplying collective ways of solving local urban problems. Feelings and intuition can guide and be put to the service of a new democracy, for life is, in essence, both spatial and emotional (Nogue Reference Nogué, Luna and Valverde2015). We interact emotionally with places by filling them with meaning that comes back to us through evoked feelings. Each geographical context transmits emotion, as does each landscape, because they are social and cultural constructions full of intangible meanings that can only be read or experimented through emotions.

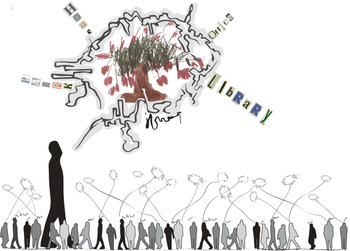

The city’s landscape acquires meaning through the significance and interpretation given to it by the particular vision of its inhabitants and visitors, making it nonexistent in the absence of an observer (Figure 47.1). Far from being a neutral space, landscape has the ability to transform itself through its two-way relationship with individuals: as they project their emotions onto it, it stimulates them, resulting in a sum of emotional geographies over the landscape (Luna and Valverde Reference Luna and Valverde2015). For this reason, a city’s complexity isn’t solely produced by the superposition of infrastructure systems, with their social and economic functions, but also by the sum of perspectives that increasingly demands for the existence of places that evoke emotions, positive feelings, and geographic roots.

Figure 47.1 The city doesn’t exist without an observer, by Diana Wiesner

The spaces each person travels through every day are key factors within the urban experience, and the enrichment of said experience materializes in places that allow for the city to be perceived through the feet, the body and the senses, places to walk, free the mind, and connect to the self (Figure 47.2). Along with the need for environments that promote urban living spaces focused on the growth of individuals, it’s also crucial to propose urban projects that are framed within an urban ecology that is coherent with the ecosystem’s regional corridors. Thus, nature’s presence has a double functionality in the urban project. While contributing to the city’s ecosystem service maintenance, it improves the quality of the urban experience, offering a range of safe meeting places that are rich in symbols and meaning.

Figure 47.2 Section of a drawing by Colectivo Bogotá Pinta Cerros, 2017. Citizens who participated printed their feelings for the mountains of the region with a 12-hand watercolor in 16 plates of 11.2 meters, representing the 57 kilometers of mountains near the city

The development of urban nature is not a “natural” process within city planning. The concept of nature in itself generates contradictions for planners who deem rivers, wetlands, mountains, and high vegetation areas to be wild places dominated by a fear of the unknown. This attitude results in a preference for high cost artificial comfort zones. Green infrastructure proposals, coherent with the aforementioned objectives, force that paradigm to be broken, for they seek to mitigate the effects of climate change and increase risk resilience strategies, procuring a balance between conservation and development.

Another important challenge for these green spaces is to provide an identity to a diverse population. Heritage values and significant elements of a place must be rescued through methodologies that inquire into hidden stories and intangible memories, thus promoting a participative construction of public spaces where people can identify with an emotional geography. In addition, I suggest that indicators associated to the quality of life of human beings be established, for example what I call “soul resilience indicators,” which measure people’s intuitive ability to manage daily risks (Figure 47.3). This concept reclaims our ability to take mankind’s adaptability and well-being into consideration.

Figure 47.3 Soul Resilience, by María Ceciia Galindo

Although humans are social beings that seek each other out, public spaces should also guarantee places for individuality, for the enjoyment of solitude, for silence, for encountering the self, and for mourning. The city is an extension of a person’s home; it should offer multiple options, and it should use biodiversity as a tool to provide infinite possibilities for countless urban souls (Figure 47.4).

Figure 47.4 A Child Holding a Painting by Walter J. Gonzalez called “My Future Bogotá”: from the south of the city he draws his image of the future

People look for distinctive elements they can identify with, which make the city feel like their own. This can only happen through the acknowledgment of the culture and of the social groups that live in a given area. In this framework, local markets, artisanal production, and traditional practices gain recognition. In the face of imposed, foreign, globalized models, citizens yearn for those symbols that might be imperfect but are their own, that bring stories back to life and add value to their insufficient free time.

The new citizen assumes his role like a musician in an orchestra, in which effective results are delivered through synchronization and group work, eliminating any type of protagonism. An urban concert could be achieved by a conductor-less orchestra, like the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra: a unique ensemble in which the musicians decided that instead of a conductor, they would all share in the responsibility of musical decisions (Figure 47.5). Could a city be conducted with the sum of citizen initiatives focused on the concepts of justice, equality, resilience, sustainability, and security, without the need for a sole governor? Is it possible that we’re in a process of change, in which instead of focusing on the search for new city ideals, we’re centering on the advocacy of a new citizenship, one that is capable of interpreting a symphony of democracy (Luna Reference Luna and Valverde2015) that yields more just, beautiful, emotional, and human cities?

Figure 47.5 Symphony of Democracy, by Diana Wiesner in collaboration with Daniela González