Refine listing

Actions for selected content:

28471 results in Edinburgh University Press

The Spanish Lady Cannot Speak: Katherine Mansfield and ‘Miasmic Modernism’

-

-

- Book:

- Katherine Mansfield, Illness and Death

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Published online:

- 12 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 30 November 2023, pp 105-120

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

4 - Texts

-

- Book:

- Divination and Philosophy in the Letters of Paul

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Published online:

- 02 June 2023

- Print publication:

- 30 November 2023, pp 133-162

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

The Deadliest Game of Snooker: Katherine Mansfield’s Great War Revisited

-

-

- Book:

- Katherine Mansfield, Illness and Death

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Published online:

- 12 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 30 November 2023, pp 57-70

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Notes on Contributors

-

- Book:

- The Didi-Huberman Dictionary

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Published online:

- 02 June 2023

- Print publication:

- 30 November 2023, pp 250-254

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Index

-

- Book:

- Divination and Philosophy in the Letters of Paul

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Published online:

- 02 June 2023

- Print publication:

- 30 November 2023, pp 231-240

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Index

-

- Book:

- Katherine Mansfield, Illness and Death

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Published online:

- 12 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 30 November 2023, pp 207-220

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Introduction: On Categories and Comparisons

-

- Book:

- Divination and Philosophy in the Letters of Paul

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Published online:

- 02 June 2023

- Print publication:

- 30 November 2023, pp 1-26

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Katherine Mansfield, ‘The Cowiness of the Cow’ and Medical History

-

-

- Book:

- Katherine Mansfield, Illness and Death

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Published online:

- 12 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 30 November 2023, pp 71-89

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Entries A–Z

-

- Book:

- The Didi-Huberman Dictionary

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Published online:

- 02 June 2023

- Print publication:

- 30 November 2023, pp 7-226

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Conclusion: Divination and Philosophy in Paul

-

- Book:

- Divination and Philosophy in the Letters of Paul

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Published online:

- 02 June 2023

- Print publication:

- 30 November 2023, pp 197-204

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

5 - Signs

-

- Book:

- Divination and Philosophy in the Letters of Paul

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Published online:

- 02 June 2023

- Print publication:

- 30 November 2023, pp 163-196

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Katherine Mansfield, Illness, Recuperation and Re-enchantment

-

-

- Book:

- Katherine Mansfield, Illness and Death

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Published online:

- 12 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 30 November 2023, pp 191-202

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Creative Writing

-

- Book:

- Katherine Mansfield, Illness and Death

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Published online:

- 12 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 30 November 2023, pp 141-142

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Acknowledgements

-

- Book:

- Katherine Mansfield, Illness and Death

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Published online:

- 12 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 30 November 2023, pp vii-vii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Introduction

-

-

- Book:

- Katherine Mansfield, Illness and Death

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Published online:

- 12 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 30 November 2023, pp 1-2

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

‘At the Bay’

-

-

- Book:

- Katherine Mansfield, Illness and Death

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Published online:

- 12 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 30 November 2023, pp 157-157

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Frontmatter

-

- Book:

- Divination and Philosophy in the Letters of Paul

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Published online:

- 02 June 2023

- Print publication:

- 30 November 2023, pp i-iv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

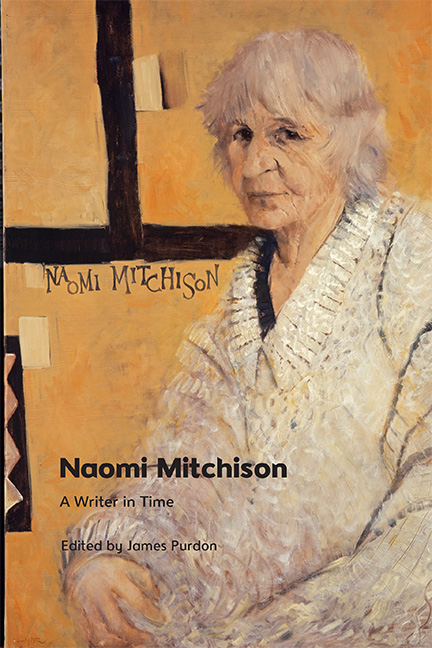

Naomi Mitchison

- A Writer in Time

-

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Published online:

- 18 November 2023

- Print publication:

- 31 March 2023

Film Adaptations of Russian Classics

- Dialogism and Authorship

-

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Published online:

- 18 November 2023

- Print publication:

- 31 March 2023

The Complete Magazine Stories of F. Scott Fitzgerald, 1921-1924

-

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Published online:

- 18 November 2023

- Print publication:

- 31 May 2023