Refine search

Actions for selected content:

33 results

Donor Requirements and CSO Performance: A Comparative Analysis of Core and Project Funding Mechanisms in Swedish Development Cooperation

-

- Journal:

- Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations / Volume 36 / Issue 6 / December 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 03 February 2026, pp. 1030-1043

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Resource-Based Accountability: A Case Study on Multiple Accountability Relations in an Economic Development Nonprofit

-

- Journal:

- Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations / Volume 25 / Issue 3 / June 2014

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 01 January 2026, pp. 772-796

-

- Article

- Export citation

6 - Philippines’ Rapid Geothermal Growth

-

- Book:

- Governing Energy Transitions

- Published online:

- 26 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 16 October 2025, pp 130-160

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

4 - Regulatory Evolution of Renewable Energy in Indonesia

-

- Book:

- Governing Energy Transitions

- Published online:

- 26 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 16 October 2025, pp 61-92

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

5 - Indonesia’s Slow Geothermal Evolution

-

- Book:

- Governing Energy Transitions

- Published online:

- 26 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 16 October 2025, pp 93-129

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Governing Energy Transitions

- A Study of Regime Complex Effectiveness on Geothermal Development in Indonesia and the Philippines

-

- Published online:

- 26 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 16 October 2025

-

- Book

-

- You have access

- Open access

- Export citation

6 - Market-Friendly Human Rights

-

- Book:

- Latin America and Human Rights Politics in West Germany, 1973–1990

- Published online:

- 18 October 2025

- Print publication:

- 18 September 2025, pp 223-263

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

3 - Remittance Machines

- from Part I - Separation Anxieties

-

- Book:

- Foreign in Two Homelands

- Published online:

- 31 August 2024

- Print publication:

- 31 October 2024, pp 137-174

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Aiding Higher Education with Export Expansion in the Developing World

-

- Journal:

- World Trade Review / Volume 22 / Issue 5 / December 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 July 2023, pp. 608-628

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

10 - Hazards from the Global South (1970–1972)

-

- Book:

- Trading Power

- Published online:

- 14 October 2022

- Print publication:

- 03 November 2022, pp 296-326

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 3 - From the Local to the Global

-

- Book:

- African Peacekeeping

- Published online:

- 13 January 2022

- Print publication:

- 03 February 2022, pp 99-128

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

5 - NGOs and Development

- from Part III: - Conduits of World Culture

-

- Book:

- The NGO Moment

- Published online:

- 01 October 2021

- Print publication:

- 14 October 2021, pp 99-116

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

5 - NGOs and Development

- from Part III - Conduits of World Culture

-

- Book:

- The NGO Moment

- Published online:

- 01 October 2021

- Print publication:

- 14 October 2021, pp 99-116

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Conclusion

- from Part IV - A People’s Compassion

-

- Book:

- The NGO Moment

- Published online:

- 01 October 2021

- Print publication:

- 14 October 2021, pp 175-185

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

2 - Putting Down Roots

- from Part I - The Ends of Empire

-

- Book:

- The NGO Moment

- Published online:

- 01 October 2021

- Print publication:

- 14 October 2021, pp 34-54

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Conclusion

- from Part IV: - A People’s Compassion

-

- Book:

- The NGO Moment

- Published online:

- 01 October 2021

- Print publication:

- 14 October 2021, pp 175-185

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Introduction

-

- Book:

- The NGO Moment

- Published online:

- 01 October 2021

- Print publication:

- 14 October 2021, pp 1-14

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Introduction

-

- Book:

- The NGO Moment

- Published online:

- 01 October 2021

- Print publication:

- 14 October 2021, pp 1-14

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

2 - Putting Down Roots

- from Part I: - The Ends of Empire

-

- Book:

- The NGO Moment

- Published online:

- 01 October 2021

- Print publication:

- 14 October 2021, pp 34-54

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

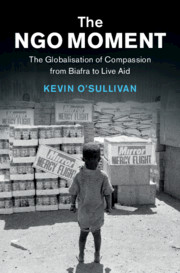

The NGO Moment

- The Globalisation of Compassion from Biafra to Live Aid

-

- Published online:

- 01 October 2021

- Print publication:

- 14 October 2021