1.1 Why a book on China’s innovation challenge?

Over the past four decades, China has evolved from being largely isolated and irrelevant to the world economy to having the world’s second-largest economy, and it is widely expected to have the largest economy in the near future.Footnote 1 In the process, China went from having a largely agricultural economy, with over 80 percent of population in the countryside, to becoming a major industrial economy, with less than 30 percent of population working in agriculture. Without repeating well-known historical details, the economic liberalization that began in 1978 was accompanied by a national policy that created surplus labor in the rural economy and unleashed a migration to the free-trade economic zones, which became hubs of low-cost, labor-intensive manufacturing for exports. In this respect, China followed the strategy of Japan after World War II, of South Korea under President Park Chung Hee, and of Taiwan under the Kuomintang. Exports were the source of national income that financed massive investment in infrastructure (roads, railroads, electric power, hydropower, flood control, nuclear power, airports, etc.), new cities, housing, and supporting supplier industries. China also attracted and encouraged unprecedented foreign direct investment (FDI) combined with policies that required sharing and transferring needed technologies. Even as exports increased, a new consumer society was being created that needed almost every imaginable amenity. As a result, it built a foundation for sophisticated industrial capabilities in mature industries that has given rise to globally competitive firms in areas such as construction, high-speed rail, heavy engineering, shipbuilding, and steel making, to name a few important sectors.

Even as consumption increased, China also continued to benefit from very high savings rates. In 1981 (three years after the liberalization of the economy), the savings rate was about 20 percent of the gross domestic product (GDP). In 1988, it increased to 30 percent, and since 1988 it has averaged 40 percent. The high savings rate has been ascribed variously to the social, political, and financial uncertainties felt by households in China due to economic liberalization, the decreasing state ownership that reduced the government’s participation in providing social welfare such as health care and pensions, and the one-child policy. Chinese people could no longer count on the government for social welfare, in particular retirement benefits. The need to save for retirement was also a direct consequence of the one-child policy, which places the burden of caring for aged parents on a single son or daughter. Chinese parents also were motivated to save so that their children could obtain a high-quality education, whether at home or abroad. A lack of certainty about property rights as well as the underdeveloped financial infrastructure and lack of investment options for building wealth also led Chinese to keep money in bank accounts.

Regardless of the reasons for the high savings rate, it enabled the Chinese government to underwrite enormous investments in infrastructure, housing, new cities, state-owned enterprises (SOEs), space programs, national defense, and the like. However, more recently the persistent high savings rate has prompted many economists to argue that it has slowed the growth of a consumer economy that would have the potential to shift the economic basis of the Chinese economy from an overreliance on exports and infrastructure investment to final consumption.

This breakneck growth has come at a very high human cost and includes the growth of a huge migrant population; family separation due to the need for parents to leave their children with grandparents so that they can pursue attractive jobs in regions other than the one of their residence; generations of families without access to social welfare, health care, or education;Footnote 2 and pollution of air, water, and soil on an unimaginable scale. The scale of the economic transformation also resulted in the wasteful allocation of resources, manifested in overbuilding (roads that go to nowhere, new airports with little activity, idle factories, and empty buildings in new cities, etc.) as well as the arbitrary displacement of citizens from land by local and central governments – the last of which created an easy source of revenue as well as widespread corruption. Together or separately, all of these threaten the popular legitimacy of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and create an uncertainty that could affect continued economic growth and development.

Since 1978, China has also made enormous investments in education, including higher education. In 1991, China’s R&D investment was RMB 15.08 billion ($2.83 billion), or approximately 0.7 percent of GDP; in 2013, R&D investment increased to RMB 1.185 trillion ($191.44 billion), or approximately 2.01 percent of GDP. The increase in the share of GDP overall was fueled not only by the expansion of resources devoted to research but also by an economic growth rate of more than 8 percent annually over the period (World Bank 2015). As a result, in purchasing power parity terms, China has become the second-largest spender on R&D in the world and may have even surpassed the United States (OECD 2014). This is a clear indication of the Chinese government’s commitment to increasing the economy’s innovative capacity (State Council 2006; World Bank 2013). The critical issue is whether the massive investment in R&D, 74 percent of which comes from the corporate sector (OECD 2014: 292), can be converted into innovations that can increase the value added and the productivity of the Chinese economy.

Although there can be little doubt that, until now, the bulk of Chinese research has not been truly world class, the rapidity of the improvement in breadth and depth is unprecedented (Fu Reference Fu2015). In terms of technological achievements, China is the first developing country to have a manned space program (BBC 2003), to possess the ability to design and build supercomputers, and to give rise to world-class telecommunications firms, to name only a few.

Since the publication of the seminal paper by Robert Solow (Reference Solow1957), the role of innovation in economic growth has become widely accepted (Aghion, David, and Foray Reference Aghion, David and Foray2009; Kim and Nelson Reference Kim and Nelson2000; Landau and Rosenberg Reference Landau and Rosenberg1986; Nelson and Romer Reference Nelson and Romer1996).Footnote 3 Recognizing the importance of imitation in the early days of a country’s attempts to build an advanced economy (Westney Reference Westney1987), Ashby’s (Reference Ashby1956) Law of Requisite Variety underlines the importance of enabling innovation through either the acquisition of new technology or its indigenous development in the new ecosystem. In the early stages, much depends on enabling processes of “imitation” to create the basis for new capabilities (for a discussion of this at the organizational level, see Ansari, Fiss, and Zajac Reference Ansari, Fiss and Zajac2010). China has been very effective at adopting and imitating technologies through various means, from FDI, technology licensing, and judicious acquisitions abroad to outright copying. Success at acquiring and assimilating more advanced technologies or entering into higher value-added technological fields is greatly contingent on building the institutions and social conditions that provide the requisite absorptive capacity (Cohen and Levinthal Reference Cohen and Levinthal1990; Lewin, Massini, and Peeters Reference Lewin, Massini and Peeters2009). In reality, there are many instances in which the attempted transplantation of practices and even far simpler physical assets such as machinery to unprepared regions has utterly failed because the necessary absorptive capacity did not exist or because the technological gap was too great (Lee, Chapter 5, in this volume). Thus, the transformation of any economy that aspires to drive growth through knowledge creation and innovation depends on previous investments in building human, organizational, and infrastructural assets so that it can encourage and harness innovation as an engine of economic growth and development.

The choice of Xi Jinping as president of China coincides with a widespread recognition that the economic policies that undergirded China’s rapid growth likely have reached their limits. Two pillars of the economic miracle have reached diminishing returns or are near exhaustion. First, the migration of surplus labor from the rural economy to the cities and the industrial sectors is ending. Although less than 30 percent of the population still resides in rural areas, the bulk of this population cannot be mobilized due to age, poor health, and lack of education (see, e.g., Du, Park, and Wang Reference Du, Park and Wang2005). Second, continuing the massive internal investment rate in infrastructure projects is not sustainable largely because the most productive projects have already been completed, resulting in diminishing returns (or even no returns at all). A case can be made that President Xi sees his mission as continuing and entrenching the hegemony of the CCP. This may be the key underlying reason for the sustained and intensive anti-corruption campaign being waged under the sole control of the CCP (with no involvement or participation by the public at large) and the urgency it feels to continue growth and avoid a “middle-income trap.”

The dilemmas faced by Chinese policymakers are vexing. The CCP believes that its legitimacy depends, in large part, on delivering economic growth. For Xi, previously employed strategies to escape the “middle-income trap” entail a transition to more democratic institutions that would threaten the power of the CCP: in his view, the examples of such transitions in South Korea and Taiwan are unacceptable for China to follow.Footnote 4 Thus, since 1978, the adoption of market mechanisms for organizing economic activity has become acceptable particularly when integrated with government-driven economic or social initiatives, while political liberalization is viewed with much greater suspicion. Indeed, Justin Yifu Lin (Chapter 2 in this volume) advocates such a policy, combined with an emphasis on technological upgrading, which in combination are intended to increase the value-added output of Chinese industries. Similarly, the rise of companies such as Alibaba, Baidu, Netease, Sina, Sohu, Tencent, and Xiaomi have identified the digital service economy as a powerful new engine of economic growth.Footnote 5 Beijing, Hangzhou, Shanghai, and Shenzhen have vibrant startup ecosystems, indicating the possibility that China can succeed in building innovatory and entrepreneurial capabilities that could evolve into new powerful drivers of economic development.

It is clear that China aspires to – indeed, believes that it must – develop an innovative economy. Since 2005, China has aggressively increased its domestic expenditures on R&D at a compound annual growth rate of approximately 20 percent (from $55 billion in 2005 to $257.8 billion in 2013). However, as many people in the government recognize, China must eliminate the many institutional barriers to innovation and entrepreneurship that still exist, as well as transform its university-based science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) teaching and research (World Bank 2013).

1.2 Scholars differ in their views on China’s prospects

Scholars, however, differ in their view of how easy or difficult it will be for China, with its one-party political system, to develop an indigenous model that will be successful in creating a knowledge- and innovation-based economy.

1.2.1 The optimistic view

The optimistic view is advanced in Chapter 2 by Lin. China has a rich history of invention, and there is no reason to believe that Chinese people inherently cannot be innovative. Before the rise of the West, China was the global leader in technology, having invented paper, printing, the compass, and gunpowder, among a plethora of other inventions, centuries earlier than they appeared in the West (Needham Reference Needham1954). The admiration of European travelers such as Marco Polo for Chinese science and technology is evident from texts that circulated in the thirteenth, fourteenth, and fifteenth centuries (Adas Reference Adas1989). However, as Gordon Redding (Chapter 3 in this volume) points out, these centuries of leadership were followed by many centuries of stagnation. Yet, as Lin argues, since the economic liberalization unleashed by Deng Xiaoping (the de facto leader, though without an official title as such) in 1978, the change has been dramatic. There is no doubt that China is capable of innovating (see, e.g., Breznitz and Murphree Reference Breznitz and Murphree2011). The question today is how innovative the Chinese can become, in contrast to the previous belief that China could not possibly be innovative. To put it even more succinctly, how far can China go?

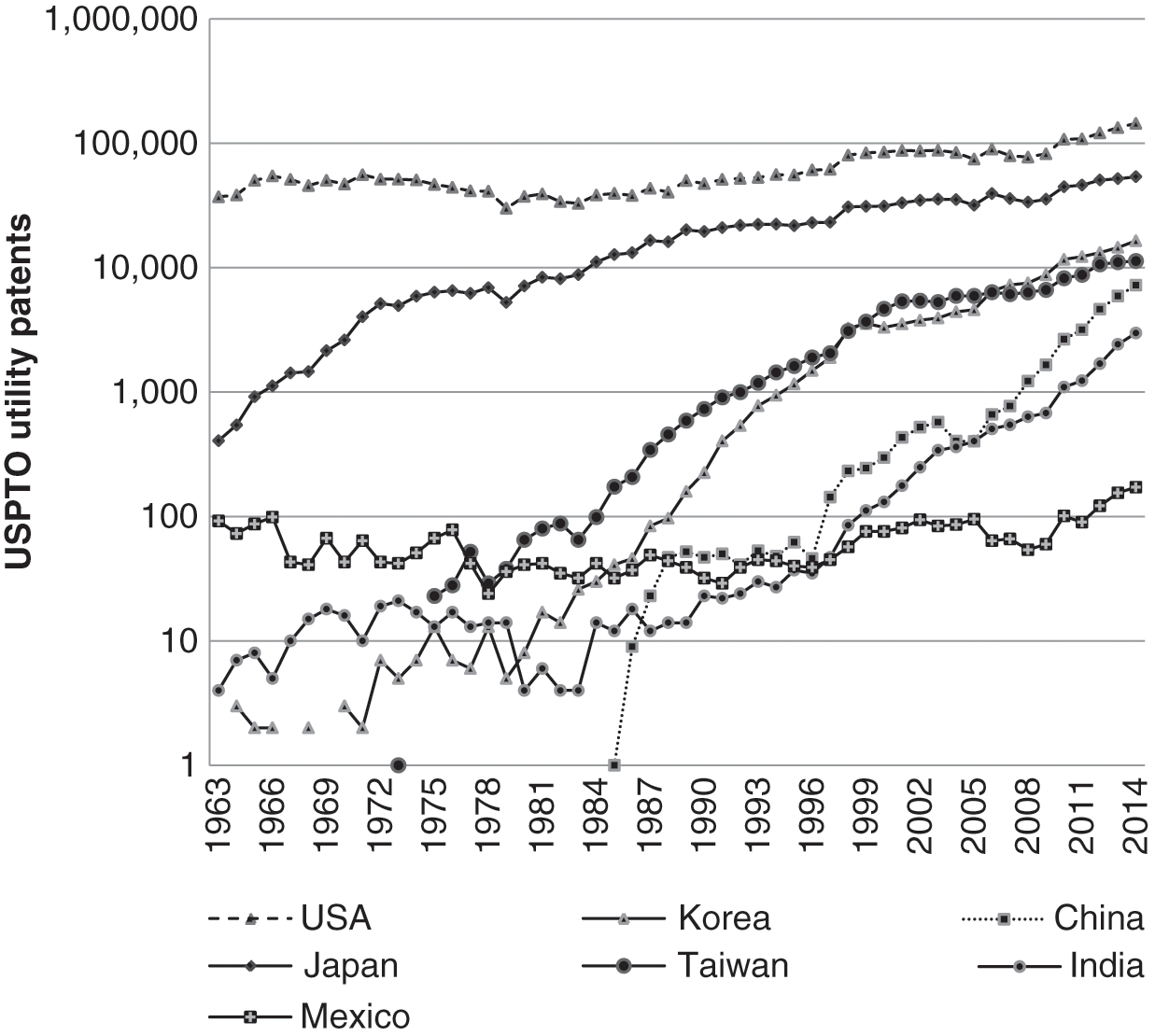

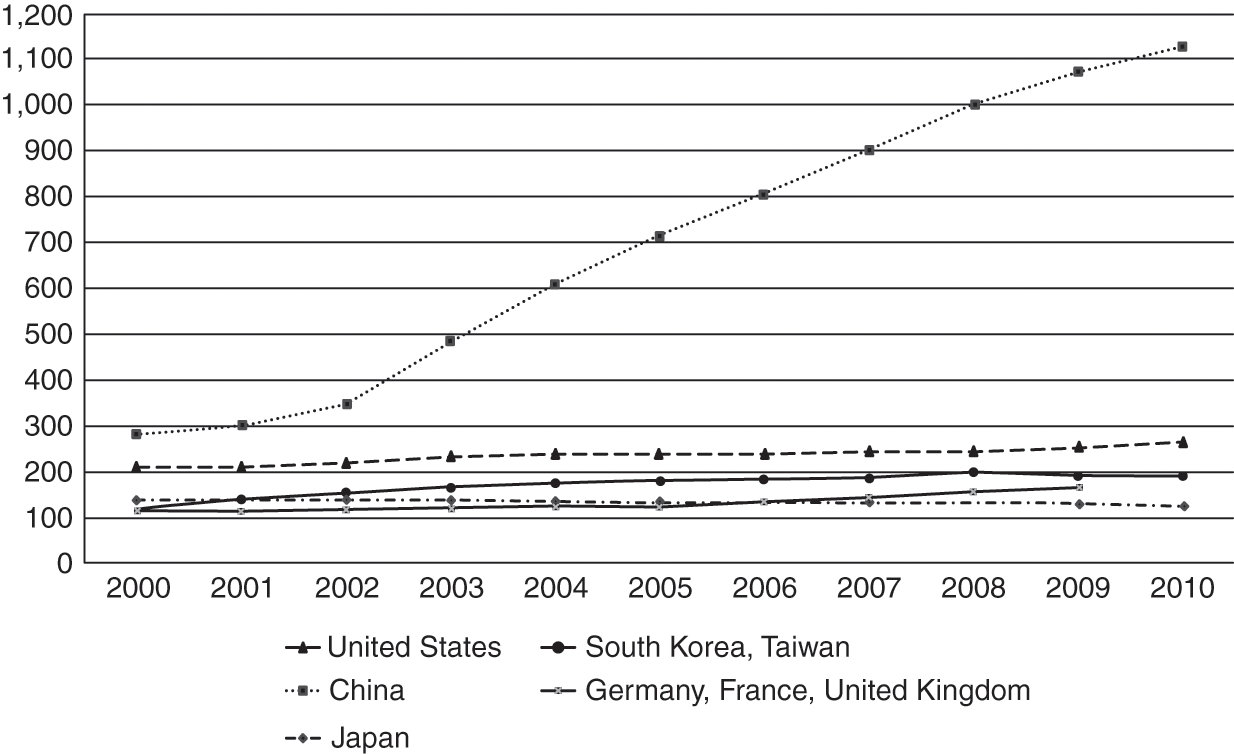

Innovativeness can be measured in a wide variety of ways. One of the most common measures is patenting (for a detailed discussion, see Cheng and Huang, Chapter 7, in this volume). As Figure 1.1 indicates, the number of Chinese patents registered with the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) has increased dramatically and is following a pattern similar to the one by Japan in the 1960s and Taiwan and Korea beginning in the 1980s. Whether this pattern will continue for China is uncertain, but it provides evidence for the optimists that China’s innovative capacity is increasing dramatically.

Figure 1.1 USPTO utility patents granted for selected countries (1963–2014)

China recognizes the imperative of developing and building a new growth model centered on innovation. Most recently, this national priority has been reaffirmed by Premier Li (Reference Li2015), who has called for greater efforts to encourage innovation in science and technology, stating that innovation is the “golden key” to China’s development. He stressed the need for breakthroughs in important technologies, for more people to start science and technology-based businesses to transform their talent into productivity, and for China to create a fair and open environment for these firms by removing “obstacles that hold back startups and innovation.”

Upgrading of universities. The first modern Western-style universities were established in the 1890s. After 1911, when the Qing dynasty was overthrown, the new republican government under the Nationalist Party (Kuomintang) made scientific learning one of its priorities and sent Chinese students to both the United States and Japan (Hayhoe Reference Hayhoe, Philip and Selvaratnam1989). Yet, by any measure, Chinese universities were hopelessly behind the global frontier. In 1949, when the CCP won the civil war against the Nationalists, Chinese universities were in shambles. Immediately upon taking power, the CCP adopted the Common Program, which declared that natural science should be placed at the service of industrial, agricultural, and national defense construction (Hayhoe Reference Hayhoe, Philip and Selvaratnam1989) and, presumably, any technologies developed should be transferred to the productive sectors of the economy.

After it rose to power, the CCP adopted the Soviet model of economic development, with the Chinese Academy of Sciences specializing in basic research, while various research institutes were tasked with applied research and universities were relegated to teaching (Liu and White Reference Liu and White2001). The Cultural Revolution of 1966–1976 disrupted education across the board, especially at Chinese universities and research institutions. As a number of chapters in this volume point out, in 1978, in the aftermath of the end of the Cultural Revolution two years earlier and China’s opening up spearheaded by Deng, it was recognized that scientifically and technologically China badly lagged behind not only the United States, Europe, and Japan but, increasingly, some of its Asian neighbors, dubbed “the Asian Tigers.” In the years that followed, a plethora of new policies were introduced to encourage “socialism with Chinese characteristics” (i.e., blending socialism with markets) and improve China’s global scientific and technological standing.

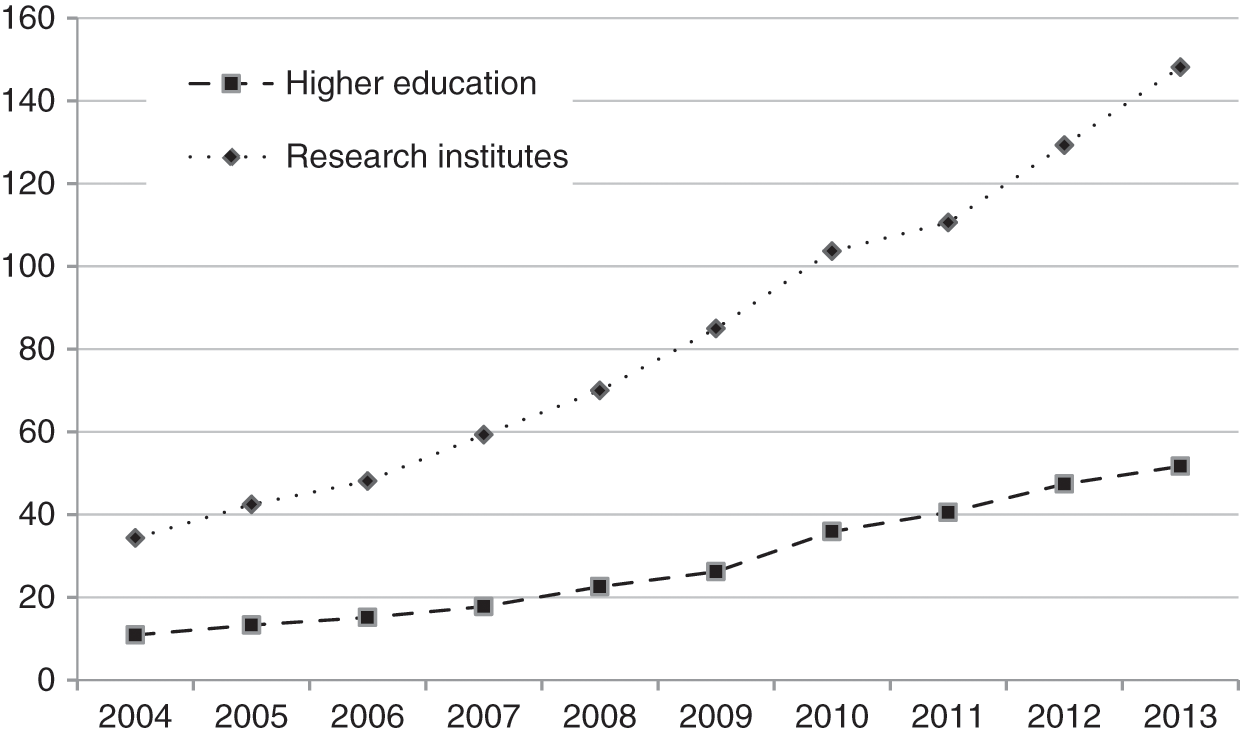

In 1978, the third plenary session of the eleventh CCP Central Committee concluded that the connection between academic research and industrial needs was weak, and new policies were introduced to encourage Chinese research institutions to address social and economic development (Chen and Kenney Reference Chen and Kenney2007). In the early 1980s, because of a severe national budget crisis, university budgets were cut dramatically. However, in the 1990s, research funding for top universities increased dramatically, in the overall environment of expanding university and research institute R&D funding, particularly through the 985 Project, which began in 1998, and massively increased research funding for selected groups of universities, with the goal of moving them into the ranks of top-tier elite global research universities (on recent growth, see Figure 1.2).Footnote 6 This is also reflected in the pursuit of sixteen huge national science and engineering projects identified by the State Council in 2006. Each of them addresses major technologies deemed to be of strategic importance for the Chinese economy, national defense, and overall competitiveness. From 2004 to 2013, both university and research institute R&D expenditures increased at a compound annual rate of 18.9 percent and 20.55 percent, respectively – in nine years, R&D funding roughly quintupled.

Figure 1.2 Chinese government funding for R&D in universities and research institutes (in billions of yuan) (2004–2013)

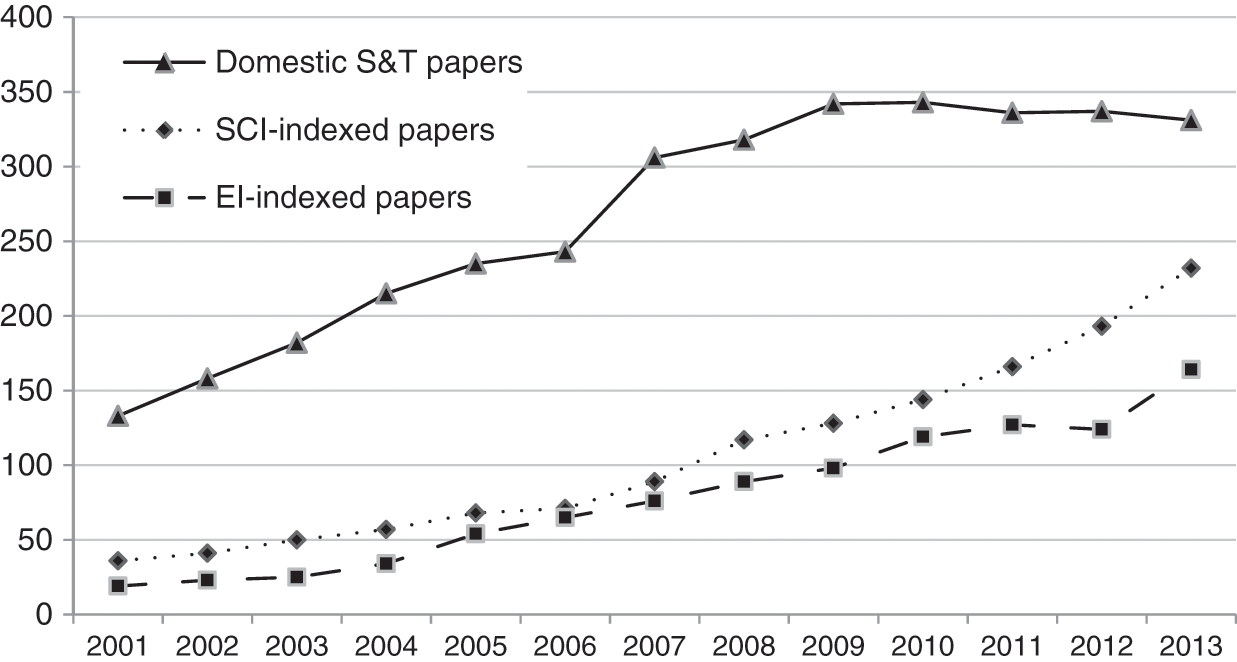

The growth in research funding was reflected in an increase in Chinese academic publications. The growth in publications is documented in Figure 1.3. Domestic publications increased dramatically until 2009 but then leveled off, in large measure because the Chinese government changed policy to encourage publication in leading international journals. This can be seen in the fact that publications listed in the Science Citation Index (SCI) and Engineering Index (EI) continued to increase. On the assumption that international journals have a more rigorous peer-review process, this growth in citations is an indication that Chinese R&D capacity has increased in quantity and also in scientific relevance.

Figure 1.3 Domestic S&T papers by higher education, and Chinese S&T papers published in international journals and indexed by SCI and EI (in thousands of papers) (2001–2013)

As Menita Liu Cheng and Can Huang show in Chapter 7, the number of university patents has increased dramatically. However, many of these patents have been criticized as being of little or no value. Much of the increased patenting activity is in response to government pressure for “results” and to incentives that reward volume, not scientific or technical significance. The weakness of university technology transfer has been diagnosed as a combination of weak and unclear intellectual property (IP) protection, lack of research of sufficiently high quality and commercial relevance, and lack of absorptive capacity by Chinese firms (Chen, Patton, and Kenney Reference Chen, Patton and Kenney2015). Of course, patents and licenses are only a small component of the overall contributions of research universities to creating an innovative economy. These observations suggest that, while Chinese university R&D has clearly improved in volume and quality, multiple obstacles remain to be surmounted before this research can contribute directly to increasing the innovative capacity of the Chinese economy. Yet, indirectly, the experience that students are gaining in world-quality research is providing a trained cadre of individuals with research skills that should be valuable for firms intent upon increasing their capabilities.

Improvements in venture capital funding. Since 2008, China has had the second-largest venture capital (VC) market in the world, and, since 2000, more VC-financed startups from China have been listed on US markets than those of any other country (see Jin, Patton, and Kenney Reference Jin, Patton and Kenney2015). Douglas Fuller (Chapter 6 in this volume) points out that domestic Chinese VC firms, in contrast to Western VC firms operating in China, are largely unwilling to invest in early-stage firms and concentrate on safer late-stage investments (see also Cheng and Huang, Chapter 7, in this volume, on cooperation between foreign and domestic venture capitalists). Despite the many obstacles, ably described by Fuller, China has been one of the most dynamic VC markets in the world with both domestic and leading global investors.

The dynamism of the local VC-financed ecosystem is due in no small measure to the fact that the Chinese government protects its telecommunications and many Internet industries from outside competition. The enormous electronic and Internet-obsessed Chinese market severely limits foreign competition, creating enormous market openings for indigenous firms. This protection has been positive in that it allowed the formation of a powerful entrepreneurial ecosystem. Yet, with the exception of a few makers of video games, Chinese Internet firms have had little success internationally. Thus, the Chinese VC industry, while large, remains autarchic, funding innovations that, though successful in the domestic market, have little impact outside China. Whether this internal focus will result in globally competitive VC-financed technological developments or new business models in the future is uncertain, and the recent stock market disorder may not augur well for VC investing in the future.

China has many opportunities and advantages compared to almost every other country at a comparable level of development. We elaborate here on the most important ones.

Size of the market. For previous global innovation leaders, domestic market size was of great importance. The race for colonies at the end of the nineteenth century was, in large measure, a race for markets (Hobson Reference Hobson1902; Lenin Reference Lenin1916).Footnote 7 Of course, overseas markets have been important, but the size of the Chinese consumer and producer markets is increasingly significant. In the case of China, exports grew from only 8.9 percent of GDP to an astonishing 35 percent in 2006, after which it began to gradually decline to 22.6 percent in 2014. It was not that the exports declined in absolute terms but that the domestic market was growing relatively more rapidly.

As Yves Doz and Keeley Wilson (Chapter 10 in this volume) point out, the size of the Chinese domestic market is staggering. Beginning in 2010, China had the highest level of automobile sales in the world, though sales have begun to decline in 2015. In 2013, 23 million automobiles were sold in China, the most ever for any country (Hirsch Reference Hirsch2015). A similar situation holds in smartphones: even with a slowdown in sales, in 2014 Chinese consumers made nearly one-third of the entire world’s purchases (Kharpal Reference Kharpal2015). The patterns in automobiles and smartphones are repeated in nearly every sector of consumer goods and services, such as the Internet, computers, solar photovoltaics, household appliances, and producer goods such as machine tools and construction equipment. Even in industries such as pharmaceuticals, due to its aging population, China is viewed as a critical market.

As the domestic market grew, it also changed from one in which low-quality, unsophisticated products were acceptable into one where consumers began to demand higher quality and design (Doz and Wilson, Chapter 10, in this volume). For example, Apple’s largest market outside the United States is now China (Popper Reference Popper2015). This desire among many Chinese for quality extends to products ranging from electronics and makeup to food. This desire for enhanced quality and consumer choice offers Chinese manufacturers significant opportunity for upgrading and gaining market share. Thus, Chinese producers have enormous avenues for potential growth.

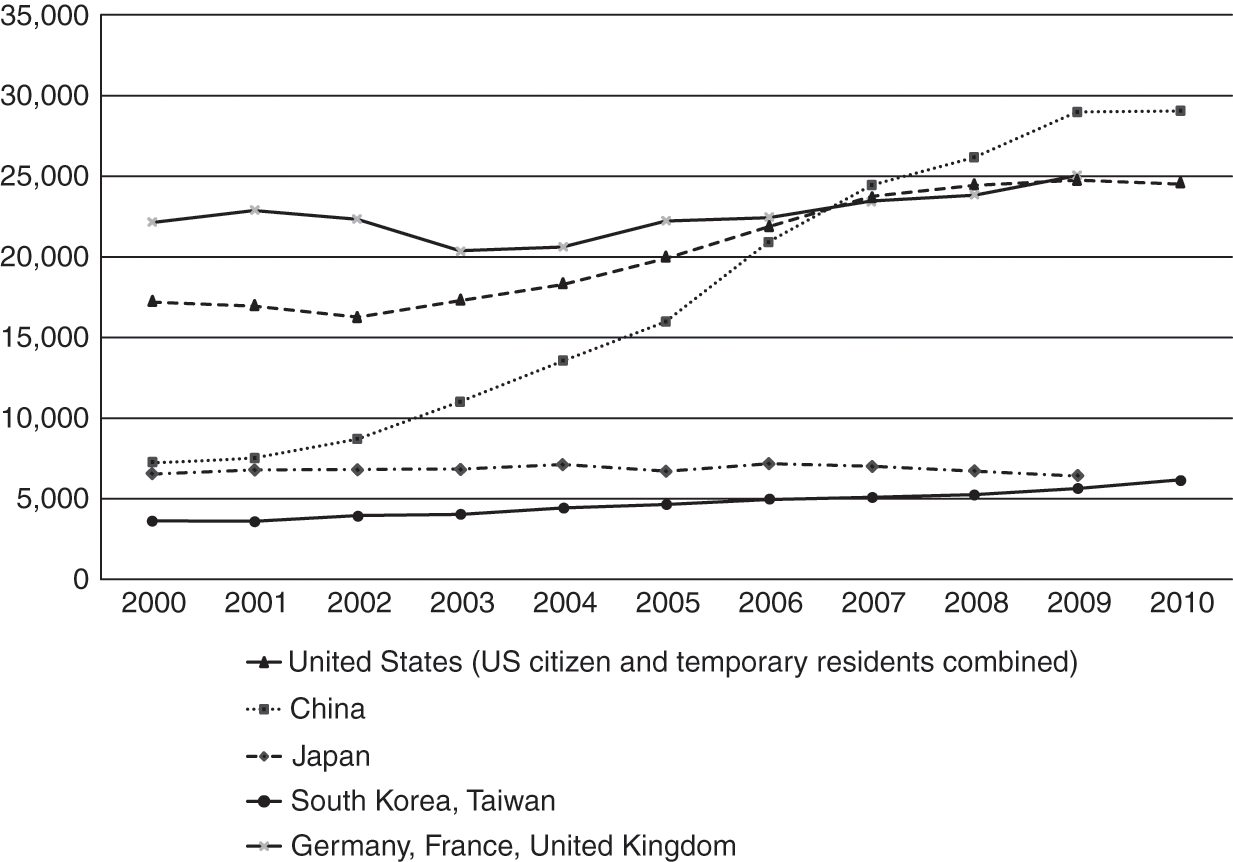

Science and technology workforce. The sheer size of the Chinese economy and education system and the emphasis on investing in human capital focused on science and technology by increasing the capacity of universities to educate scientists and engineers mean that China has built an enormous STEM workforce. As Figures 1.4 and 1.5 show, the number of STEM graduates is remarkable and has grown much more rapidly in China than in developed countries. As discussed in Chapter 11, debates continue over the quality of these STEM graduates at both the bachelor’s and PhD levels. However, the willingness of US universities to admit a significant number of them for further study suggests that some are of high quality. This suggests that China is likely to be able to populate its industry with technical talent. However, the obsession in policy circles with engineering talent leads us away from considering how innovative these engineers are and will be.

Figure 1.4 Bachelor’s degrees awarded in natural sciences and engineering in the United States and various countries by year (2000–2010) (in thousands)

Figure 1.5 PhDs awarded in natural sciences and engineering in the United States and various countries by year (2000–2010)

The overwhelming emphasis on technical talent may come at the expense of creating the innovative designers and artists that make products desired by consumers. In today’s competitive, design-intensive world, producing incremental innovations and undifferentiated commodities for low-end consumers is unlikely to lead to the kind of higher value-added activities that characterize advanced economies. As China’s economic evolution proceeds, transformational innovation and design creativity will be much more critical than graduating an ever-increasing number of traditionally trained engineers (see also the discussion in Chapter 14). Transforming the STEM postgraduate education system to nurture creativity, radical innovation, and design sensibility is recognized as a top-priority national goal. However, as discussed in Chapter 14, the challenges and complexities of unleashing and institutionalizing such a transformation in the ecology of Chinese higher education are unfortunately far more difficult than training more engineers.

1.2.2 The pessimistic view

Although China has improved its technological capabilities significantly in the past four decades, moving from a middle- to a high-income economy is qualitatively different and much more difficult than moving from a low- to a middle-income society. As Gordon Redding (Chapter 3 in this volume) articulates forcefully, the level of complexity of interactions required in a high-income country is orders of magnitude greater than in a middle-income country. To cope with this complexity – according to the chapters in this volume by Redding (Chapter 3), Michael Witt (Chapter 4), and Chi-Yue Chiu, Shyhnan Liou, and Letty Y.-Y. Kwan (Chapter 14) – China will require a decentralization of power based on self-organization and trust, a process that will be extremely challenging to implement in a system conditioned by history and culture to value centralization, which today is reinforced by the CCP’s imperative of maintaining control. At this stage of China’s evolution, it is difficult to imagine the new institutional regimes and mechanisms that would bring about an “innovation society.” Even if the CCP were willing and able to relinquish its monopoly on power, the pessimistic view identifies important barriers in the existing configuration of Chinese society that will make it difficult to create a truly innovative country that will be able to catch up with high-income countries.

Governance challenges due to size. The scale of China’s population and geography, coupled with multilayered ethnic and cultural diversity, would make governance difficult under any system, but in a centralized system, it is even more challenging. However, since establishment of the Qin dynasty in 221 BCE, by Emperor Qin Shi Huang, China has only known centralized forms of government. Decisions made at the center must make their way down the bureaucracy and be translated into action in different local environments. As Douglas Fuller (Chapter 6 in this volume) notes, the mid-level government officials do this translation, and the outcomes are visible in the variation in the innovation ecosystems of Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou (Breznitz and Murphree Reference Breznitz and Murphree2011; Crescenzi, Rodríguez-Pose, and Storper Reference Crescenzi, Rodríguez-Pose and Storper2012).

China’s size, diversity, and scale create enormous coordination difficulties for a command economy that can be expected to stymie change, particularly when it threatens the discretionary power and control over resources and policy implementation and even over enactment of local economic agendas of lower-level government functionaries. The same institutional configuration enables considerable policy experimentation – a flexibility noted by Lin (Chapter 2) and analyzed in detail with respect to the national initiative to leapfrog India in business services outsourcing, analyzed in Chapter 12. At the same time, China’s huge scale gave it advantages in attracting FDI to build the automotive and other industries and global capacity in railroads, heavy engineering, and construction simply because of unprecedented investment in infrastructure as well as in science and technology. But it also has its drawbacks in terms of responsiveness and building shared interpretations of lessons learned.

System of intellectual property. Many observers in China and elsewhere have noted that the weak Chinese IP regime is an important obstacle to gaining full advantage from knowledge creation and innovation, even though this very weakness has facilitated the imitative importation of technology that contributed to rapid Chinese industrial development. As many of the contributors to this book suggest, the weak protection for IP might now present an obstacle to domestic investment in R&D, as other domestic firms can easily copy their innovations. Cheng and Huang (Chapter 7 in this volume) outline the actions that the Chinese government has taken to solve important problems with IP protection and suggest that still more change can be expected. Chiu, Liou, and Kwan (Chapter 14 in this volume) go even further, arguing that this tendency toward imitation is deeply rooted in group cultural norms that make it difficult to give voice to ideas that are outside the in-group consensus. These cultural factors are further reinforced by an absence of institutional trust and top-down institutional and bureaucratic controls in the R&D resource allocation process.

Corruption. China, like so many other developing countries, suffers from deep and endemic corruption. Apart from the qualms one might have about Western values-centric measures of transparency and corruption, even the Chinese government recognizes the seriousness of corruption for both the further development of the Chinese economy and its own legitimacy. This has led to serious anti-corruption campaigns with severe penalties for misdeeds. One unintended consequence may be that mid-level bureaucrats and business executives will refrain from creative activity for fear of being caught up in these anti-corruption campaigns. However, the more important question may be whether corruption can be controlled in the authoritarian environment and relatively opaque operations of the Chinese economy and political and regulatory systems.Footnote 8 Addressing corruption may be difficult, due to concern that unleashing social movements to expose it could lead to popular mobilization that might tarnish the image of the CCP or even threaten its hold on power. Thus, corruption creates a significant dilemma: escaping the middle-income trap almost certainly requires a dramatic decrease in corruption and the forces that generate it, but a concerted attack on corruption might call into question the CCP’s legitimacy.

Environmental degradation. The chapters in this book do not directly address the impact of Chinese economic growth on the physical environment, both in China and globally, but, by any measure, this impact has been enormous and might be catastrophic, especially with respect to global climate change.Footnote 9 Rising global sea levels could inundate cities such as Shanghai and Hong Kong and have a damaging effect on global and Chinese agriculture. Moreover, pollution has already had and is likely to continue to have a devastating impact on China including a veritable epidemic of pollution-related illness and a despoliation of land and water resources. Chinese officials are taking these threats seriously as the potential for economic disruption from them have become manifest. As of 2015, China is a leader in producing and introducing green technologies (Mathews Reference Mathews2014). Whether these efforts will be sufficient to offset all the environmental effects of Chinese growth is uncertain. What is certain is that China faces an environmental crisis characterized by extraordinarily high levels of air, land, and water pollution and a rapidly growing environmental movement that might expand to the point of threatening the CCP’s legitimacy. Addressing these multiple crises is sure to complicate China’s continuing economic growth, even as they offer ample opportunity for innovation (see, e.g., Economy Reference Economy2011).

Increased global tensions. Massive changes in global economic and political strength unfortunately have often been accompanied by conflict. For example, the rise to power of Germany, the United States, and Japan in the Pacific during the late nineteenth and first half of the twentieth centuries was accompanied by two global conflicts. Although the world is currently far from any such conflict, Chinese muscle flexing is causing regional tension, which could have unpredictable effects on China’s further development and progress. Although possible geopolitical changes are outside the scope of this book, they could affect China’s responses if economic stagnation occurs.

1.3 A preview of the chapters

This book explores the opportunities and barriers that China faces in building a more innovative economy at different levels of analysis. The authors of each chapter also present their perspective on a particular policy or research agenda at their level of analysis.

1.3.1 Socioeconomic and political analysis

Chapter 2, by Justin Yifu Lin, was mentioned above in our optimistic viewpoint on China’s ability to continue to grow and escape the middle-income trap. In addition to having a distinguished career as an academic economist both in the United States and China, Lin served as the chief economist of the World Bank from 2008 to 2012 and has had close acquaintance with the problems in many developing countries as well as China. He argues that every economically backward country can grow 8 percent annually if it pursues industrial policies consistent with its level of development.

In the chapter, he offers a six-step framework for how developing countries can formulate effective policies for economic growth. He calls his theory “new structuralism” because, as in the development theories prominent in the 1950s and 1960s, he sees a central role for the state in selecting specific industries for development and building the physical and institutional infrastructure to allow entrepreneurs to establish firms that will drive growth in those sectors. The theory differs from the “old” structuralism by emphasizing that a country must choose industries in which the country has a latent comparative advantage – by this, he means those that are not too distant from its existing capabilities and in which it can exploit factor advantages such as inexpensive labor. New structuralism rejects the neoliberal “Washington Consensus” theories that, when adopted in countries such as Chile or Russia, failed to bring about sustained economic growth.

Reviewing world economic history over the past 300 years, Lin contends that all countries that successfully caught up with more advanced industrialized countries implemented policies that are consistent with his “new structuralism.” Given that China’s GDP is only a quarter of that of the United States and that other East Asian countries at China’s current level of development grew for an additional two decades at a rate of around 8 percent before slowing down (e.g., Japan from 1951 to 1971 and South Korea from 1977 to 1997), Lin believes that China can continue to grow at around this rate to exceed a middle-income level. For this to happen, Lin contends, China needs to continue its policy of gradually upgrading its economy by targeting sectors slightly beyond its current capabilities and consistent with its comparative advantages and let the market gradually play an ever-larger role in the economy. Because, in some sectors of the economy, China is already approaching the technological frontier, Lin emphasizes that it will become increasingly important for it to become an innovator in these sectors, rather than relying on imported technology. From a larger perspective, Lin’s contribution suggests that China is becoming sufficiently confident to propose a countermodel to the US-inspired Washington Consensus model.

Not all scholars are as optimistic as Lin that China will be able to escape the middle-income trap. Chapter 3, by Gordon Redding, provides a strong counterpoint to Lin’s confidence. Redding is skeptical that the overall governance structures that allowed China to transition from a poor to almost a middle-income level will allow it to continue its growth trajectory and achieve the level of GDP per capita of high-income countries such as South Korea, Taiwan, or Japan. Although Redding welcomes Lin’s call for policies tailored to the specific development stage of an economy, he suggests that scholars incorporate insights from history, sociology, and political science into an analysis of China’s future challenges. He argues that even two countries at the same state of development can differ substantially in societal organization and thus require different approaches to stimulate economic growth. Japan had a very different social structure and history from China’s. Therefore, just because Japan grew at a rate of 8 percent for twenty years after 1951, when it was at the same level of development as China is today, it does not mean that the same will occur in China.

Redding contends that economic growth at low levels of development is qualitatively different than it is at higher levels of development. Moving from a middle-income to a high-income economy, in his view, increases the level of internal economic complexity at an exponential rate. He is doubtful that China’s hierarchical governance structure can deal with this level of complexity. In his reading of economic history, all existing examples of countries that have moved into the high GDP per capita group have accomplished this through a decentralization of decision-making and a devolution of power to a “middle level” that can invent new forms of stable order that are beyond the reach of the central authority. Aside from this devolution of power, Redding believes that the ability to innovate and trust strangers are two other societal characteristics that must develop in order for the wealth creation frontier to be reached. Redding does not believe that China can achieve an advanced economy without fundamentally transforming these key aspects of Chinese society.

These two chapters, expressing almost diametrically opposite positions, are the ends of the continuum on which the other chapters are located. They all lie somewhere between Lin’s optimism and Redding’s skepticism regarding the ability of China’s economy to attain high income.

While Lin drew his optimism regarding China’s future in part from the South Korean experience, Michael Witt, based upon a detailed analysis of Korea in Chapter 4, is somewhat skeptical about China’s ability to reproduce the Korean experience in escaping the middle-income trap. Witt observes that historically China has not had difficulty in inventing physical technologies but has found it challenging to develop the institutions and social structures that can fully exploit those technologies to upgrade its economy. He believes that, going forward, China’s root problem is not that it lacks the capacity for developing physical technologies but, rather, that it does not have the proper institutions to achieve a high-income economy. Drawing upon the theory of national business systems, he observes that high-income countries (e.g., the United States and Germany) can organize their economies very differently. Moreover, he notes that, over time, different national systems have not converged to adopt a single optimal model but, rather, have maintained their differences, thus suggesting that there is considerable path dependence in the development of each system. With this grounding, Witt finds strong similarities between the business systems in China today and those in South Korea around 1980. However, as it moved from having a middle- to a high-income economy, Korea responded by becoming much more democratic. In contrast, the CCP seems intent on continuing its monopoly on power in China. Witt concludes that if the CCP is successful in maintaining its control over all aspects of society, China will fall into the middle-income trap. If, for some reason, the CCP loses control over China’s transformation process, the country could follow the same path as Korea and achieve a high-income economy.

Keun Lee has devoted much of his career to analyzing the reasons as to why some countries are successful in catching up economically while others are not. In Chapter 5, he notes that at least thirty countries have fallen into the middle-income trap and describes the various mechanisms by which this can happen. Lee’s core argument is that catching-up by middle-income countries requires that they invest in sectors with short technology cycles. Cycle time here refers to the speed with which technologies change or become obsolete as well as the speed and frequency at which new technologies emerge. In sectors with a long cycle time, incumbent firms have a key advantage over new entrants. Hence, it is advantageous for middle-income countries to specialize in sectors with a short cycle time. His theory of catch-up bears striking similarities to Lin’s, but he explains that his theory is particularly relevant for countries that are in the upper-middle-income bracket. Lee’s first conclusion is that China has upgraded its education system sufficiently to develop the human resources needed for innovation. His second and more important conclusion is that China has specialized in industries with a short cycle time. For these reasons, he is confident that China will not fall into the middle-income trap for lack of innovative capability.

In Chapter 6, Douglas Fuller postulates that many of the very institutional arrangements that contributed to China’s rapid development are now paradoxically becoming impediments to further development. He identifies three drivers of Chinese expansion – government gradualism, local incentives to local officials, and, the one he stresses most, financial repression – that are now obstacles to escaping the middle-income trap. “Financial repression” refers to government policies that keep interest rates lower than they would otherwise have been. This repression, he argues, has particularly benefited SOEs and led to a massive misallocation of capital. These obstacles are exacerbated by misguided government industrial policy and, ultimately, the Leninist party–state system. Even though these earlier policies were vital to China’s success, he believes future success will depend on whether the government can overcome vested interests and reorganize the financial system and state–business relations sufficiently to allow continued economic growth.

Many observers and a number of chapters in this book single out China’s system of IP protection as an obstacle to further economic growth. In Chapter 7, Menita Liu Cheng and Can Huang briefly outline the evolution of the system, identify a number of weaknesses, and discuss policy initiatives underway to address them. The Chinese IP system was imported from the West but has evolved to become uniquely Chinese, with a complicated governance system. For Western observers, the enforcement of IP protection is of greatest concern, and the authors suggest that this is gradually being addressed. The scale of patenting in China is remarkable, as today the State Intellectual Property Office processes 32 percent of the world’s total, and this is accelerating at a breathtaking pace – from 2012 to 2013, it increased 26 percent. The authors show that this is driven by government policies. First, China has an intermediate patent category, utility patents with a lower standard of examination and uniqueness that encourages trivial patents. Second, the government offers generous incentives to defray patenting costs, making it essentially costless, and tax breaks that can even make it profitable to patent. The result of the government’s intense pressure and the utility patent system is the filing of an enormous number of “junk patents” with little commercial value. Finally, they single out the university technology transfer system for reform. This chapter provides the reader with a deeper understanding of the current state of Chinese IP policies and its likely future directions.

1.3.2 Enterprise-level analysis

In Chapter 8, John Child places his discussion within the context of global interest in small and medium-size enterprises (SMEs), which are already an important component of the Chinese national innovation system. He believes that one of the ways to avoid the middle-income trap is for China to increase the innovatory capacity of its SMEs, which are already an enormous part of its economy. The competitive advantage of Chinese SMEs in the past was based on their ability to produce relatively mature products at low cost. However, their future success will depend increasingly on their ability to engage in product innovation. Child explores the situation of SMEs in China through the lens of four widely used management theories: the resource-based view, the institutional perspective, the network perspective, and the entrepreneurial perspective. Concurring with a number of the other chapter authors, Child argues that the SOEs are particularly problematic for SMEs in terms of competition, access to capital, and ability to recruit top-quality talent. Moreover, along with Redding, Child identifies lack of trust and overreliance on informal networks as blockages to increased SME innovation. As a result, even when Chinese SMEs are innovative, it is in only an incremental way, retarding their ability to advance to a stage in which they can introduce novel products and services. Given the importance of SMEs globally and in China, there is ample opportunity for empirical research that can contribute to theory testing and building in this area. We return to this point in the concluding chapter.

During the past two decades, China has benefited from more FDI than any country in the world except the United States (UNCTAD 2014). Moreover, this investment has gone toward commercial activities ranging from sales and marketing to manufacturing and R&D. From a national innovation systems’ perspective, Simon Collinson, in Chapter 9, examines the relationships between local Chinese firms and their multinational enterprise (MNE) partners and the bidirectional learning that results. Technology transfer, learning, and spillover effects have long been recognized as key channels for enhancing the ability of firms, industrial sectors, and economies to innovate and compete. Collinson’s chapter, based on survey data and personal interviews, explores the complex relationship between MNEs and their Chinese partners. He finds that Chinese firms gain access to assets, technology, resources, and capabilities, while MNEs benefit from local knowledge and connections. Both the success and the types of learning from these relationships vary widely by industry. Using an in-depth case study of the civilian aerospace sector, he finds that capabilities were not transferred but, rather, were reshaped to adapt to the local environment. He found that Chinese government intervention meant to spur technology transfer and promote indigenous innovation, while often successful, negatively affected the sustainability of those partnerships. This chapter provides unique and granular insights into the scale, in terms of numbers and depth, of interaction and knowledge transfer that occurs between local firms and MNEs. Collinson offers an important perspective on how this form of knowledge acquisition can be transformed into innovation as part of China’s efforts to escape the middle-income trap.

It is only recently that Chinese MNEs have developed significant offshore operations instead of simply exporting to foreign markets. In Chapter 10, Yves Doz and Keeley Wilson explore this phenomenon. They note that, in contrast to MNEs from developed countries, Chinese MNEs did not enter the global economy by first exploiting home-based advantages and then advancing to capture and leverage host-country advantages. Instead, Chinese MNEs are pioneering a new model that leverages their enormous and somewhat protected domestic market, lagging home-based resources, rapid internationalization, and access to capital to acquire firms with superior technical capabilities in developed countries. This effort is part of China’s quest for foreign assets, such as advanced technology, to upgrade current activities and capture higher value-added segments of the global value chain.

Doz and Wilson suggest that Chinese MNE acquisitions are often in fields with mature technologies and are used to learn, explore, and remedy disadvantages. In effect, acquisitions allow them to purchase the wide varieties of knowledge (technical, marketing, and organizational) that leading firms in developed countries have built. For Chinese firms, doing so offers another avenue for increasing the knowledge content of their products and contributes to escaping the middle-income trap. Doz and Wilson highlight the hurdles that Chinese firms face in building global innovation networks by integrating their acquisitions. They conclude by calling for more research on the new global innovation networks that leading Chinese firms are building.

1.3.3 Sectorial-level analysis

Chapter 11, by Silvia Massini, Keren Caspin-Wagner, and Eliza Chilimoniuk-Przezdziecka, directly addresses China’s opportunity to develop a new growth model built on knowledge creation and innovation. It does so by comparing innovation systems and policies in India and China to gain a deeper understanding of whether China is overtaking India as the global source of innovation. This chapter complements and extends the contributions by Cheng and Huang (Chapter 7) and Fuller (Chapter 6) by describing a long-evolving trend that is driving companies in developed countries to seek external sources of service and innovation activities and disperse them across the globe. Companies in developed countries are increasingly sourcing innovations through market channels such as licensing, joint ventures, mergers and acquisitions, as well as through many forms of outsourcing.

The chapter also discusses new trends in which companies increasingly unbundle higher value-added activities, such as innovation projects and outsourcing specific projects to innovation providers, as well as a new trend of employing STEM freelancer talent located anywhere in the world on demand. The underlying drivers of these trends are advances in information and communications technologies, pressure to increase the productivity of product development and research activities, the desire to exploit knowledge clustered around the world, and the need to cope with a shortage of domestic STEM talent. These dynamics frame the opportunities for economies such as China’s to participate in global knowledge creation and develop their domestic innovation capabilities to support new engines of economic growth.

The chapter concludes that China’s STEM workers are discovering new opportunities by finding employment on demand as freelancers and that the best and brightest, who have pursued graduate education in the West (often with the support of nationally funded research grants), are increasingly finding ways to remain outside the country. Both trends benefit companies in the developed countries while increasing the brain drain in China.

Chapter 12, by Weidong Xia, Mary Ann Von Glinow, and Yingxia Li, is a detailed study of the complexities and challenges that China faces in implementing a specific national initiative consistent with the framework outlined by Lin (Chapter 2). The specific case involves upgrading the domestic business services outsourcing industry to compete globally. The Chinese government framed the initiative as “Leapfrogging India’s IT Outsourcing Industry.” It was the first central initiative intended to upgrade the domestic business services outsourcing industry as one strategy for moving beyond manufacturing exports.

The chapter describes the history of China’s national strategy to “leapfrog” India in services outsourcing. By 2013, Indian business services outsourcing accounted for $86 billion (55 percent) of the global offshore outsourcing market, compared with China’s $45 billion (28 percent). Dalian was considered the model city for entering the global market for business services outsourcing because it had already developed a specialty of providing business services outsourcing for Japanese and Korean companies and accounted for 13 percent of China’s total in 2013.

The chapter serves as a reminder of institutional and contextual barriers involved in implementing central industrial policies and the limitations of creating competition between model cities when their prior experience has been in building and developing manufacturing export bases. Service and innovation industries have entirely different institutional requirements, as discussed in other chapters, and it will require more than trial-and-error competition between cities to build the capabilities for competing on the bases of knowledge creation and innovation.

1.3.4 Individual, organizational, and cultural analysis

Chapter 13, by Zhi-Xue Zhang and Weiguo Zhong, advances the argument that most Chinese companies are innovation handicapped. The authors contend that Chinese companies – whether state- or privately owned – do not have the mind-set or managerial and organizational capabilities to become innovative enterprises. The barriers that this chapter identifies are the absence of transparent rules for conducting business and the multilevel dependence of business owners and managers on personal relationships (guanxi) with government officials, CCP leaders, and other business people at various levels. Managers at SOEs perceive career advancement to be linked to satisfying government-set political and economic targets. Private business owners depend on maintaining “good relationships” with local officials and on delivering performance that is aligned with the goals of the local government. The lack of transparency in the conduct of business puts a high premium on managing the enterprise’s dependence on its political and regulatory environment.

To understand the current conundrum, it is important to recognize that, after the economic liberalization in 1978, entrepreneurship grew apace, as firms in every sector could succeed just by satisfying pent-up demand. Firms only had to produce in quantity but did not have to upgrade product quality, have innovative designs, or develop new products – much less surpass competitors with disruptive products, technologies, or marketing strategies. This environment did not encourage innovation. However, several new companies founded in recent years can serve as models for innovation-based enterprises. The authors portray firms such as Tencent, Alibaba, and Huawei as examples of privately owned technology startups that are world class, although in each case success was facilitated by central government policies that excluded direct global competitors. The chapter also notes that certain regions of China, such as the provinces of Guangdong, Zhejiang, and Jiangsu, have historically been more entrepreneurial and can serve as the leading edge in China’s efforts to achieve an innovation-driven economy.

Chapter 14, by Chi-Yue Chiu, Shyhnan Liou, and Letty Y.-Y. Kwan, makes the case that the huge investment by China to upgrade its STEM human capital (e.g., investment in university education and attraction of talented returnees) by itself will not create a new transformational innovation-based economy. The authors analyze in detail institutional challenges discussed by Redding (Chapter 3) and complement analyses by Fuller (Chapter 6) and by Zhang and Zhong (Chapter 13). They identify institutional and cultural constraints that hinder the creation of a vibrant national innovation system. Mirroring the analysis by Redding (Chapter 3) regarding the role of “personalism” and the lack of institutional trust, the chapter documents the dynamics of control mechanisms and the role of in-group identity as negatively affecting the adoption of innovative ideas. Even when the government makes special efforts to entice Chinese researchers to return to China with promises of “cultural leniency,” in reality the system rewards loyalty and group consensus. Studies on Chinese STEM returnees and of science and technology also highlight the lack of transparency, which acts as a barrier to intellectual curiosity. To bring about more radical innovation, the authors call for institutional and cultural environments that protect individual rights, discourage group centrism, and encourage intercultural learning.

Rosalie L. Tung, in Chapter 15, explores the extent to which scholars of cross-cultural management recognize the increasing importance of China and Chinese firms in global trade. Since the economic reforms were introduced in 1978, China has received massive FDI and, as noted by Doz and Wilson in Chapter 10, has recently begun to engage in large FDI of its own. Analyzing the evolution of cross-cultural research and how it has dealt with the rise of East Asian economies, she finds that the existing cross-cultural theories have significant shortcomings because they (1) treat countries such as China as having a single homogenous population and culture, rather than recognizing the heterogeneity within one country; (2) posit that the cultural distance between any two agents leads to negative outcomes; (3) assume that the impact of cultural distance between two actors is not influenced by the firms in which the actors are embedded; and (4) bundle individual distance measures between agents into aggregates. She concludes that, to be helpful to MNEs operating in China and Chinese MNEs doing business in other countries, cross-cultural research should be reframed and focus on building more comprehensive models of comparative management that are better able to deal with the complexities of the contexts in which managers find themselves.

1.4 Some final thoughts

China is an outlier among emerging countries seeking to attain a high-income economy. Most recent examples of countries that have made this journey, such as Japan, Taiwan, Singapore, Hong Kong, and especially South Korea, can be instructive. But China’s scale, long history of centralized authoritarian government, culture, complexities, and enormous contradictions, with tendencies and countertendencies, preclude any definitive attempt to prescribe how China could succeed in making innovation its “golden key” to development. Obviously, regardless of future developments and its ability to become an innovative economy, China is not going away as a global economic and political force. Even if its progress stopped, the entire world would have to continue to adjust to the changes already underway in China.

We hope we have whetted your appetite for reading many of the chapters. While we expect that many readers will want to read the chapters in order, others might wish to start with later chapters and then work their way backward. In our final chapter, we draw on all the chapters to offer some reflections on what we have learned.