In his darkly poetic and posthumous novella The Last Summer of Reason, Tahar Djaout portrayed the rise of a fascistic theocracy as seen through the eyes of an Algiers bookseller, a man whose youthful hopes of ‘a humanity liberated from the fear of death and of eternal punishment’ have been drowned by the rise of an ultra-militant Islamism, its ‘dream of the purification of society’ in ‘blood and all-consuming flood.’1 Born in 1954 in Oulkhou, a village perched in sight of the sea on the Kabyle coastline just east of Azzefoun, Djaout was ten months old when the war of independence began. After university he became a journalist for Algérie Actualité and by the late 1980s was one of Algeria’s foremost literary talents. In January 1993, he helped launched an independent newspaper, Ruptures, which was as critical of the state since Boumediene’s coup as it was of the Islamists. On the morning of 26 May 1993, he was shot in a parking lot as he left his home in the west Algiers suburb of Baïnem. After seven days in a coma, he was pronounced dead on 2 June.

Who? Whom? – And for What?

Officially attributed to an Islamist terror group, Djaout’s killing was never transparently investigated. It became one of the first, and perhaps the best known, of many murders, of journalists, intellectuals and artists but also of many thousands more Algerian women, children and men, to become caught in a controversy over the attribution of culpability, whether to some faction of the Islamist insurgency, to some fraction of the state’s security services or to some combination of the former manipulated and instrumentalised by the latter. Other murders added to a mounting death toll that became incalculable, and to a horror that seemed incomprehensible: 21-year-old Karima Belhadj, a secretary in a police station, was killed on her way home from work in April 1993, leading sociologist Mohammed Boukhobza, at his home in Algiers in June 1993, beloved raï singer Cheb Hasni, outside his parents’ apartment in Oran in September 1994, and acerbic journalist Saïd Mekbel, in an Algiers pizzeria in December 1994; the left-wing, feminist architect Nabila Djahnine, in a Tizi Ouzou street in February 1995, the Bishop of Oran Pierre Claverie who, born in Bab el Oued in 1938, had returned to Algeria in 1967 and remained there, in a doorway in Oran in August 1996, and the militant, secularist musician Matoub Lounès, on a road in Kabylia in June 1998; entire families and neighbourhoods in the Algiers suburbs and villages in the Mitidja in 1997–98, and in the districts of Blida, Medéa, Aïn Defla, Chlef, Relizane, from 1994 onwards …2 By 2002, a decade of bewildering, horrifying war was said to have taken anything between 100,000 and 200,000 lives, the routine imprecision of the estimated death toll expressing both the enormity and the unaccountability of the violence.

From the mid-1990s onwards, gnawing doubt and bitter dispute about qui tue qui? (who is killing whom?) troubled the Western media, the online public sphere and the political quadrilles danced around the Algerian crisis by the international community. It exasperated and infuriated many of those in Algeria who themselves were living with constant threats of death and saw their friends and colleagues murdered around them. The West’s seeming indulgence of Islamists, as some saw it, during the 1990s, and criticism in European liberal opinion of Algerian opposition to Islamism as indistinguishable from the military regime’s ‘dirty war’, angered those who saw a violent, intolerant and incipiently totalitarian Islamism on their doorsteps as the real threat to their lives, their families and their country. Some of Djaout’s former colleagues would be scathing that the same French leftists and liberals who mobilised against fascism in France, when the Front National’s Jean-Marie Le Pen reached the second round of presidential elections in 2002, had entertained the prospect of an FIS victory in Algeria ten years earlier. To them, Le Pen was ‘a choirboy by comparison’ with the Islamists. They were indignant that ‘terrorists’ were given asylum in France, Britain, Germany and the USA, while ‘those who were threatened with terror’ were left to face it alone because it was not the government that threatened them. They saw withering irony in the international about-face after al-Qa’ida’s attacks on the USA on 11 September 2001, the recasting of Algeria as an early victim of armed Islamism and avant la lettre line of defence in a ‘global war on terror’, which the regime spun skilfully in its favour, along with the mounting Western racism and Islamophobia that they and their compatriots now faced, irrespective of their own experiences.3 Others, perhaps equally opposed to Islamism but more inclined to credit the state with a monopoly of violence, decried the naïvely simplistic misrepresentation of the Algerian conflict as a struggle between Islamists and ‘republicans’, seeing the many irregularities, opacities and unexplained circumstances around the proliferating violence as signs of a deliberate, orchestrated campaign of deception and misinformation as well as assassination and state-sponsored terror by le pouvoir.

Within Algeria, and in the intertwined public spheres of media and migration that connected Algeria and France, each side in the argument viewed the other with impatience and incredulity. Some, fleeing for their lives from secret police threats into exile in Europe or North America, alongside European democracy and human rights activists, some of whose engagements with Algeria dated back to the war of independence, saw themselves as unmasking the lies and conspiracies deliberately built up by a regime that had resorted to terrorising its own people on a massive scale. Others, pointing out that they were still in Algeria and perhaps knew more than exiles and outsiders about what was happening to them, pointed to their unenviable choice between ‘plague or cholera’ and accused the promoters of ‘the deleterious question of qui tue qui’ not only of ‘sowing confusion’ but, implicitly, of being complicit bystanders in the violence engulfing them.4 In the global media that multiplied over these years through internet and satellite, Algeria – increasingly isolated as foreigners fled, consulates closed and exit visas became the most sought-after of commodities – became a horrific spectacle, a cautionary tale, a vicarious trauma, anything but ‘a country with people in it’.5

In these circumstances, and since the 2006 law on ‘National Reconciliation’ which criminalised in Algeria ‘declarations, writings or any other act’ bearing on ‘the National Tragedy’ of the 1990s that might ‘cause injury to the institutions [of the state] … the honour of its agents … or impugn the image of Algeria on the international stage’,6 the possibility of writing a satisfactory history of what happened in Algeria in the mid-1990s remains slim twenty years later, not because sources are unavailable – testimonies of various kinds as well as intense contemporary media coverage abound – but because, in the context of a fundamentally unresolved conflict, the tools necessary to the indispensable criticism of the sources are lacking. The competing narratives spun out of the crisis and war, each situated within the crisis itself, became aspects of the war, means of seeking understanding and self-location in relation to the violence, more than analyses of it. Recounting the war became indistinguishable from taking a position within it, uncovering ‘secret histories’ or refuting their accusations, disputes over which tended to become a grotesque rhetorical double, in the ether of the global media, of the war itself, and which became structured by their own narrative economy of political expediency, consumer demand, ‘acceptable’ opinion and a market for the sensational, the ‘secret’ and the obscene. Conspiracy theories abounded, seeking to identify a single, hidden rationality behind apparently irrational events that were otherwise beyond comprehension.7 Individual ‘testimonies’ or ‘revelations’ were valued for their supposed ability to uncover ‘confiscated truths’ more than for their own truth to be confronted with others: in place of the unanimist narratives that fell apart along with much else after 1989, Algeria in the early 2000s had a proliferation of publishing and an immense public interest in its recent past, but Algerians were given ‘témoignages instead of history.’8

Narratives of the 1990s within Algeria and outside remain deeply divided and, needless to say, the evidence of the archive or of those, within the apparatus of the state, most centrally implicated is unlikely ever to become available. In addition, the broader frames of reference that structured social-scientific accounts of the crisis as it unfolded have arguably proved actively unhelpful to understanding it. The mounting crisis from 1986 onwards that culminated with the army’s intervention and ejection of Chadli in January 1992, and then the war that escalated through the end of the decade and was winding down, unresolved and unaccountable, just as the ‘global war on terror’ began, coincided with dramatic changes on the world stage: the democratic revolutions in eastern Europe and the fall of the Soviet Union, the end of the Cold War after 1989 and the apparent ascendancy of a unipolar, neoliberal and American-led world order, then, in 2001, the challenge to that order by a utopian and sectarian, millenarian Islamism and, after 2003, its testing to overstretch by its own spectacularly delusional ambition. Then came the global crash of 2008, and the rise of a new global instability and anxiety, combined with both renewed democratic aspiration and a new wave of war across the Arab world.

The academic industries of political and economic ‘transition’ studies and those of ‘conflict management’ for ‘new wars’ that emerged in the briefly triumphal moment after 1989, and then those of ‘terrorism and security studies’ that succeeded them a decade later, were mostly interested in ‘lessons from Algeria’ that, often misunderstood, could be (mis)applied to validate highly questionable general models; they themselves proved quite inadequate to understanding Algeria.9 Between the promised ‘new world order’ that was supposed to follow the Cold War and the new wave of global fear, proxy war, neo-imperialism, terrorism and unaccountable state violence that spiralled into the twenty-first century, Algeria’s murderous decade from 1992 was framed, as it unfolded and as Algerians and others attempted to understand it, by competing narratives and interpretations – of human rights and humanitarianism, democratisation and international law, terror and counter-insurgency, religion and politics, freedom of speech and cultural difference – whose only common feature was their greater propensity to become stakes in the conflict than means of accounting for it, let alone contributing to any resolution of it.

Algeria’s history in the 1990s, then, must be seen as one of contradictory stories, of the divergent ways in which Algerians themselves sought to make sense of what was happening to them and to their country. It is perhaps the most terrible chapter of the country’s history, but – like not dissimilar stories from Rwanda or Congo, Lebanon or Iraq – it cannot be understood if it is seen simply as a spectacle of carnage. If the logics of violence themselves remain all but impossible to penetrate, and can only be accounted for hypothetically or in multiple ways, the subsequent developments in Algerian state and society, after the turn of the millennium, nonetheless illustrate important underlying dynamics. The fragility of political order, the rapidity with which it came apart and the ruthless brutality with which it was reconstituted to the benefit, once again, of a few and to the effective exclusion of the majority, demonstrated the resilience of the state’s core of coercive force despite, or because of, its disconnection from and increasingly predatory relationship to the population supposedly constituted of its citizens. The latter, for their part, would increasingly view their ruling class and its apparent ‘contempt’ (hogra) for them with irony and disgust, deriding the incompetence of hukumat Mickey (‘Mickey Mouse government’) and the self-serving privileges of tchi-tchi (chic, cossetted) apparatchiks’ families and mujahidin Taïwan (fake, ‘made-in-Taïwan’ claimants to ALN veterans’ rights). They would lament the rising rate of teenage suicide and the increase in harraga, the clandestine migration to Europe of which, each summer, dozens of young people would become victims by drowning at sea, at the same time as they, just as often, held to a sense of political community marked by a self-image of insubordination, dignity and combative national pride.

And at the same time, while the near-collapse of Algerian society in a maelstrom of blood and terror might be most apparent – the unravelling of social solidarities as neighbours were murdered in their stairwells or sitting rooms by others they’d known as children, the pervasive fear induced by car bombs in city streets and faux barrages (‘false’, insurgent-mounted control points) on country roads – at least as important, in the longer term, would be the underestimated and often unobserved endurance of society relative to both the absence and the ferocity of the ‘forces of order’, its capacity to sustain and rebuild itself amidst the destruction of insurgency and repression as it had under the ravages of colonialism and in the throes of revolution. And while both state and society thus proved more resilient than might perhaps at first appear, the relations between them too, however torn, were capable of reconstitution.

While the early 1990s saw the disintegration of social bonds as well as of the formal political sphere, and the apparent dislocation both of the state from society, and of society from itself, a formal political sphere was recomposed, from 1997, over the resilient, ‘informal’ but real core of the state. This, and its uneasy, fragile but tenacious, endurance through the regional upheavals of the ‘Arab Spring’ that began in Algeria and Tunisia in the winter of 2010, was possible not only because of the unfettered violence so ruthlessly unleashed to win the war – and not, in particular, because of any deep and abiding fear of that violence among the population at large – but rather because of the rebuilt, informal connections between the state’s centres of decision, access and patronage and local networks of support, distribution and negotiation. Algeria put itself back together, after the ‘dark decade’ (la décennie noire),10 through long-established practices of informal politics and even older institutions – jama‘a, ashira and zawiya – as well as through a recomposed, formally pluralistic party-political machinery that often doubled, or was linked to, such institutions at local and regional level. And after the devastations of utopian jihad and cynical Realpolitik, Algerians tentatively rebuilt their social space on the basis of a broad consensus of values, within which social and political divisions could be played out without recourse to arms. By 2012, Algeria was neither at peace, nor was it a pathological, traumatised society endemically at war with itself, but one engaged in a slow, episodically overt struggle over its shape and that of its polity, and over the meanings of the values – nation, religion, personal morality and social justice, the inheritance of the past and the means of moving beyond it – that its people generally held in common.

The Descent into War

The drama of 1989–92 had not, despite appearances and especially despite comparisons with what was happening at the same time in Eastern Europe, been a promising transition to democracy that was suddenly reversed by the army. It was, rather, a case of manipulative crisis management gone awry. The opening of public space to associational life – for everything from clubs for former students of particular schools to proselytising Islamic associations like shaykh Mahfoud Nahnah’s jami‘yat al-irshad wa’l-islah (the Guidance and Reform Society) – a proliferating and remarkably free media, and a massive social mobilisation, especially through near-continuous strike action across all sectors of the economy and the professions, certainly liberated and encouraged an immense outpouring of social energy and enthusiasm as well as anger and dissent, especially among younger Algerians. Journalist Hocine Belalloufi would remember that Algeria ‘was fizzing … A wind of freedom had begun to blow across the country.’11 But the conditions for the translation of Algerians’ diverse and assertive visions of themselves and their possible futures into a rule-bound, stable and mutually tolerating, substantively democratic politics were by no means in place: in fact, quite the reverse.

What quickly became the largest Islamist movement, embodied after two constitutive meetings at the al-Sunna mosque in Bab el Oued on 18 February 1989, and the Ibn Badis mosque in another Algiers neighbourhood, Kouba, on 10 March, in the FIS, was impatient and utopian, undecided about its tactical position on electoral democracy (but opposed to democracy in principle as unable to distinguish between ‘impiety and faith’12) and inclined to see its opponents, at best, as deviants who were ignorant of Islam and in need of correction and, at worst, as unbelievers or apostates who had no place in the national community. Its project was one of social moralisation rather than of governance and its militant fringes, while pushing their opponents into the arms of the army, were not above espousing violence themselves.13

The FIS drew its inspirations and its slogans from an eclectic range of influences. It claimed a filiation with Ben Badis’ pre-war reformism that was quite unjustified in terms of intellectual content or social program but very effective as a claim to the continuity of incorruptible, religiously based opposition to oppression, and more strongly asserted a claim to be the true inheritor of the wartime FLN and its revolution that corrupt apostates had stolen from the people: the FIS was thus allegedly the fils, the legitimate son, of the historic FLN. Its adherents had been influenced by the broader movement of al-sahwa al-islamiyya, the Islamic ‘awakening’ that spread in the 1980s from Saudi Arabia, Pakistan and Egypt, the writings of Hassan al-Banna and Sayyid Qutb, ideas of a ‘caliphal state’ and of a republic based on ‘consultation’ (shura): the duty of each properly instructed believer to exercise his opinion as to the government of the community, guided by the interpretation of shari‘a, under the sovereignty of God. It brought together ambitious veteran Islamists like Abbasi with younger firebrands like Benhadj alongside Mohammedi Saïd, ‘Si Nacer’, who had worked for German intelligence during the Second World War and was famous for the German helmet he wore as well as for his rhetoric and incompetence in the maquis, where he was colonel of wilaya 3 in 1956. At the same time, there was undeniably ‘a real adhesion’ among broad swathes of society to the FIS, which more effectively than other, rival Islamist movements tapped into a widespread, ‘profound attachment’ to religion and captured the enthusiasm of younger people, especially, in the cities and in peripheral neighbourhoods, for a radical vision of morality, dignity and justice.14 Against them was not only the generals’ intense dislike of the threat the FIS posed to the established system and to their own custodial sense of public order, but also a visceral anti-Islamism among other opponents of the regime. This was to be found especially, for example, among members of the PAGS who saw the contest as a life or death struggle against fascism, and the activists of the RCD, whose own political socialisation had been in the fledgling anti-authoritarian human rights movement of the mid-1980s when many of them had been imprisoned, but whose opposition to Islamism trumped their antipathy to the regime. Such divisions, which ramified throughout society, were likely to serve nothing better than the interests of the factions in power.15

It has been argued, partly because the FIS was legalised in September 1989 after five months of waiting, because of the FIS’s own relatively liberal (though also very abstract) economic program and initial lack of criticism of Hamrouche’s economic reforms, that a tacit understanding was reached by Chadli and Hamrouche with the FIS, which they hoped to instrumentalise in the service of economic liberalisation against an FLN ‘old guard’ still identified with étatist/socialist policies.16 Other accounts, by contrast, point to the legal recognition of the FIS, as well as those of the RCD, whose creation was announced by MCB and human rights activists at Tizi Ouzou on 9 and 10 February, and the Trotskyist PT (Parti des travailleurs, Workers’ Party) as having been decided by Hamrouche’s opponents in the regime. As one insider put it, all three parties were ‘born in Larbi Belkheir’s office’.17 The FIS’s founders were themselves undecided about the form their movement should take. Having originally imagined it as an umbrella organisation for the unification of da‘wa activities (the proselytising ‘call’ to what they saw as ‘true’ Islam), they rushed to adopt the form of a political party when the opportunity arose, under the February 1989 constitution, to translate their implicitly political stance into actual political action.18 The decision to legalise the party seems to have been made not by Hamrouche’s government, but by his predecessor Kasdi Merbah’s Interior Minister Abubakr Belkaïd, almost certainly at the behest of Belkheir (and Chadli?), putting Hamrouche, when he took office three days later, before a fait accompli.19

In any event, Hamrouche and his government came into a political landscape in ferment, which in the months after October 1988 had already blown away their previously preferred option of a slow and managed political opening. Given the way in which the formal multiparty system was subsequently – from 1995 onwards – recomposed around the décideurs’ rules of entry into the system, and especially the roles played in that system by the RCD (as a counterweight to the FFS), the PT (as a notional revolutionary leftist and secularist party, the only one in the Middle East and North Africa to be led by a woman, Louisa Hanoune), and the permanent presence of two, mutually balancing, legal Islamist parties, there is every reason to think that from early on in the ‘management’ of the crisis of the system in 1989, the factions of the pouvoir réel had decided on the creation and instrumentalisation of a multiparty ‘shop window’ for the regime, with party machines serving as channels both to diffuse dissent and split opposition, and as networks for clientelism and patronage. As one observer put it, ‘most of the parties they legalised [in 1989–90] were non-entities (des partis bidon)’, which, if not vanity projects like Ben Bella’s Movement for Democracy in Algeria (MDA), which had existed since 1984 without having any constituency within Algeria, were simple vehicles for distributing influence, their strings pulled by elements of the regime.20 Algeria’s reconstituted party system – put together as a remarkably rapid return to ‘constitutional legality’ in the midst of the worst of the violence between 1995 and 1997 – would be structured by an unreasonably neat choreography: two ‘Kabyle’ parties (FFS and RCD), two Islamist parties, a far-left party (the PT) to supplant the PAGS (which imploded in December 1992) and a new regime party, the National Democratic Rally (RND), created almost from nothing for elections in 1997, as well as the FLN (which would be recuperated after a stint in opposition under Mehri between 1992 and 1995), along with a large number of tiny independent parties and a few electorally insignificant groups created as personal vehicles by historic FLN figures.

This suspiciously tidy division of ‘seats at the table’ (kursis), which could be (and from 1997 onwards would be) periodically reshuffled almost at will, would serve the interests of the regime’s factional power brokers, not only in lieu of and more effectively than the old single-party façade of the FLN but, more importantly, in place of any more genuinely autonomous and plural political field, whether emerging from the old FLN, from the newer social forces of a younger generation or from a generational reconciliation that might have combined the two. The larger reform project that had been briefly imagined by the team around Hamrouche as the necessary basis for a longer-term, stable liberalisation and democratisation of the system had been destroyed in 1991 before the suspension of the formal electoral process; the latter, even had it been allowed to continue – which in the circumstances was exceedingly unlikely – would not have equated to a substantive democratisation of Algeria’s polity. Competitive party pluralism mobilised especially around mutually exclusive identity politics, the pressure of elections, and above all the opportunity of a utopian opposition party to benefit from a massive popular protest vote which, however, was hardly an overwhelming mandate for an Islamic state, all militated against deeper, structural democratic change, and pressed Algeria, instead, headlong into open civil conflict.21

Presiding over this sabotage of the country to rescue their entrenched positions from the crisis of the single-party system were the janviéristes, the army and security hierarchs who were behind the heavy-handed intervention of June 1991 and the deposition of Chadli in January 1992, who by 1997 would succeed in returning to elections with a new multiparty regime façade more in tune with post–Cold War times, and who by 2002 had maintained themselves in power by prosecuting a vicious war against the Islamist insurgency and anyone else who might threaten them, while actively preventing any negotiated political solution to the crisis that might allow all sides of Algerian society to arbitrate their own future. Whatever else about the war remained opaque and impenetrable, one thing was abundantly clear: while almost everyone else in Algeria had lost by it, they and their associates had won.

The central group of janviéristes were all of the same generation and similar backgrounds. Born mostly in the late 1930s, none had been political militants before the revolution, most had been trained in the French army before joining the ALN on the frontiers and all had risen through the ranks as professional military ‘technicians’ under Boumediene before reaching command positions in the mid-1980s. Khaled Nezzar (b.1937), who had been Chadli’s adjutant at the base de l’est and one of the first cohort of Algerian officers trained at staff college in Moscow after independence, took overall command of ground forces in 1986, was appointed chief of the General Staff in November 1988 and in July 1990 became Minister of Defence (the first time since 1965 that this post was separated from the prerogatives of the Presidency). Abdelmalek Guenaïzia (b. 1936), who deserted his post as a warrant officer in a French unit stationed in Germany with Nezzar in April 1958, succeeded him in 1990 as Chief of the General Staff. Mohamed Lamari (b. 1939), who would succeed Guenaïzia in turn as Chief of the General Staff in July 1993, was commander-in-chief of ground forces in January 1992. Benabbès Gheziel (b.1931) had been commander-in-chief of the National Gendarmerie (the paramilitary extra-urban police, run from the Ministry of Defence) since 1987. Chadli’s long-serving right hand Larbi Belkheir (b. 1938) had become Interior Minister in October 1991, putting him directly at the head of the bureaucracy and police forces as the final act of the crisis approached. Mohamed ‘El Moukh’ (‘the Brain’) Touati (b.1936) was an advisor to the General Staff; Ismaïl ‘Smaïn’ Lamari (b. 1941), a veteran of the sécurité militaire (SM), was head of its department of internal security and counter-espionage, and his immediate superior Mohamed ‘Tewfik’ Mediène (b.1939) had taken charge of the SM, which he renamed DRS (Département du renseignement et de la sécurité, Intelligence and Security Department), in 1990.22

Most of these men – Nezzar and Belkheir, in particular, but also, indirectly, ‘Tewfik’, who as a minor SM officer had been brought to Algiers from Oran under Belkheir’s wing – owed their ascension to their long-term patronage by Chadli. But some of them, most notably Tewfik, were also allegedly notable within the system for their ascension in opposition to an attempt in the mid-1980s by Chadli and two principal army figures, chief of staff Mustafa Belloucif and SM director Medjoub Lakhal-Ayat, to professionalise and modernise the army and intelligence services and to reduce the influence within them of the old ex-ALN and MALG factions whose networks within and outside the armed forces, entrenched since independence, stood in the way of establishing a more efficient, meritocratic officer corps and intelligence service (and, no doubt, new networks of influence independent of those already in place). An ex-maquisard and career soldier, Belloucif was appointed Secretary General of the Ministry of Defence (effectively the head of the armed forces, answerable only to the President) in July 1980. He was one of the first cohort promoted to the new rank of Major General in October 1984, and the following month became the first man to hold the office of Chief of the General Staff since it was abolished by Boumediene after Zbiri’s attempted coup in 1967. He became a proponent, in particular, of diversifying Algeria’s military procurement away from dependence on the USSR. Lakhal-Ayat, also a career officer, became director of the SM in 1981 and head of the new General Delegation for Prevention and Security (DGPS) within the SM, which Chadli split from the Central Directorate of Military Security (DCSA) in a reorganisation of the security services in 1987.23

Both Belloucif and Lakhal-Ayat encouraged the recruitment of a new intake of university graduates into the army and the SM, but at least some of those who joined came to observe the persistence of parallel structures of solidarity and patronage, organised both by factional loyalty and by region, in particular the importance of officers from the east of the country, the so-called BTS triangle of the region between Batna, Tebessa and Souk Ahras. Less qualified but more pliable recruits with the right connections were seen to benefit from accelerated training and promotion. Tewfik, who ‘didn’t count for much’ on his arrival, is said to have been recruited into the MALG in 1961 in Tunis from the French navy, and to have owed his subsequent career entirely to Belkheir.24 In 1986, he was made head of the Department of Defence and Security Affairs, one of Belkheir’s apanages in the Presidency, and when DCSA chief Mohamed Betchine, an ex-ALN maquisard who was also an army moderniser, was promoted to succeed Lakhal-Ayat as head of the DGPS after the bloodshed of October 1988, Tewfik took over from Betchine as head of military security. When Betchine subsequently resigned, in 1990, it was Tewfik who took over command of both departments of the SM, reorganising and greatly expanding the service under the new title of DRS. When January came, it was he who presided over the extensive powers of the secret services; and he owed his position to manoeuvres that already indicated a dangerous degree of factionalism even within them.

While undoubtedly serving their own interests and those of the system as they saw it, it is important not to assume, as many in and outside Algeria would come to believe, that the janviéristes were either a single, closely united interest group, or that this group was simply the instrument of a diabolical, neo-colonial plot. Some of them, particularly those close to the influential power broker Belkheir, could certainly be identified with a hizb fransa in terms of their own personal, political and commercial connections with elements of the French political establishment, business elite and security services. But they were not a unified bloc, and if they acted in the service of their own lucrative connections to foreign interests, they did so, too, in concert with a vision of the Algerian state, and in particular of the role of the army, that they shared with others of quite different backgrounds. Nezzar would insist on the custodial role of the ANP, established since 1962, as ‘safeguarding independence and national sovereignty’. While duly removing its officers from the FLN’s central committee after the 1989 constitutional changes, the army, he declared, could not remain ‘neutral’ in the face of what its commanders saw as threats to ‘the destiny of the nation’.25 He was joined on the HCE by Ali Kafi, whose nationalist background could not be more impeccable – he had been in the PPA before joining wilaya 2, where he was Zighout’s adjutant, participating in the August 1955 offensive and the Soummam Congress, and from 1957 to 1959 was Zighout’s successor – and Ali Haroun, the lawyer and wartime FFFLN veteran, who had worked with Abbane on El Moudjahid in 1957 before retiring from politics after participating in the first Constituent Assembly in 1963 and re-emerging in the human rights movement in the mid-1980s.

Others agreed with them as to what was to be done in January 1992. Ali Kafi held the presidency of the National Organisation of Mujahidin (ONM), a powerful mechanism for distributing and leveraging influence through networks of ALN veterans (or those claiming to be such). In 1993, a new movement, the National Organisation of the Children of Mujahidin (ONEM), was set up to transmit the same system to a new generation, modelled on the existing National Organisation of the Children of Martyrs (ONEC). In the years after independence, a tiny pension was all the state had accorded to the widows and orphans of the revolution – and sons and daughters of shuhada (‘martyrs’ to independence) experienced their status as such as a personal, familial matter, as a private grief as well as the sense of dignity that loved ones had ‘done their duty’. ‘He was dead; it was done with’: some at least, probably many, were revolted by the notion that it should be a source of lifetime rent.26 Now, such inheritances of the revolution were politically mobilised through the ONM, ONEC and ONEM, which would be called the ‘revolutionary family’, to rally anti-Islamist social forces and bolster the regime.

Another veteran revolutionary, Redha Malek, the Évian negotiator and contributor to the Tripoli program, became the president of the HCE’s rubber-stamp ‘parliament’, the National Consultative Council (CNC), and later joined the HCE itself. Malek saw Islamism as an anti-modern ‘regression’, an undoing of the revolution that threatened the life’s work of his generation, and considered that political figures like himself who backed the military intervention had ‘done [their] duty’: ‘we assumed our responsibilities.’27 Mostefa Lacheraf, the more liberal intellectual and pre-war PPA veteran who had been Malek’s colleague on the Tripoli program, agreed.28 In April 1995 these two would be the principal founders, with Ali Haroun, of a ‘modernist’ political party, the National Republican Alliance (ANR), which would have no electoral significance but was nonetheless several times awarded a ministerial portfolio.29 As Prime Minister in March 1994, Malek famously declared at the funeral of the murdered playwright Abdelkader Alloula in Oran that ‘It’s time fear changed sides’ (La peur doit changer de camp). Fifteen years later, he was unrepentant at the phrase, which, he said, was intended ‘to give courage to the population’ that was ‘wavering’, and to counter ‘defeatists, accomplices, and opportunists’ whose ‘misinformation’ and ‘conspiracy-obsession’ (complotite) expressed the anti-Algerian Schadenfreude of a ‘colonial revanche’.30 At the time, his declaration announced an escalation and generalisation of hostilities.

The janviéristes’ coup was thus supported by a broad coalition of actively mobilised interests, as well as by more diffuse anti-Islamist opinion, while being rejected by others, especially the FFS and FLN, which for a short period became an opposition party. Questions of the coup’s ‘constitutionality’ – which Nezzar and others defended, referring to their ‘Novembrist’ action in defence of the integrity of the revolution, while others decried its blatant illegality – were largely beside the point, since the one consistent feature of Algeria’s politics had long been its lack of law-bound government. This formal problem, however, was underlain by a more serious, deeper one, revealed in the widespread adoption both by establishment figures outside the army’s core elite and among the opposition, including ‘democrats’ on the left, of the view that the crisis was a security matter that should be ‘managed’ by the army, not a political problem requiring resolution through a political process, debate and compromise.31 Once again, the military took, and was largely granted, precedence over the political.

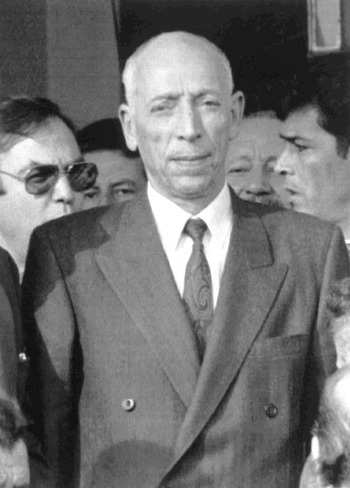

The HCE, presiding over a dramatic political crisis, was nonetheless opposed by the three parties (FIS, FFS and FLN) that had garnered most votes in December 1991, and although it had some real support within Algeria – from the PAGS and the RCD, the powerful UGTA, intellectuals and cultural figures mobilised to ‘safeguard Algeria’ – and the backing of the French establishment, it lacked any broader international legitimacy. Redha Malek, who had served as an intermediary during the US embassy hostage crisis in Tehran in 1980, flew to Washington where he pressed for support of the regime against potential Islamist takeovers across the region.32 But the HCE, having resurrected the old principle of collegial leadership and assumed the powers of the Presidency, nonetheless needed a credible face. After some hesitation, they agreed to invite Mohamed Boudiaf out of exile in Morocco to become president of the Council. The 73-year-old veteran revolutionary, untouched by compromise or corruption since 1962, would represent ‘honesty’. For those who thought like Redha Malek, the austere Boudiaf, in ‘suit and tie, clean-shaven’, would incarnate ‘modernity’ in contrast to the Islamists’ gowns, beards and ‘regression’.33

A few months earlier, Boudiaf had been interviewed by an Algerian journalist who had found him at his very modest brickworks at Kenitra, on the Moroccan coast north of Rabat, preparing clay for moulding himself, with his sleeves and trousers rolled up.34 Suddenly called back to politics after thirty years in opposition and exile, he took a similarly direct approach to the task at hand in Algeria: he certainly was not content to be a front for the décideurs. He arrived in Algiers on January 16. While pursuing the repression of armed Islamism, he also had thousands of detained FIS sympathisers who, he said, were no more than ‘stone-throwers’, released.35 Above all, he ordered major investigations into corruption, and reached out directly to younger Algerians, to whom he promised a re-foundation of the state. Completely unknown to the younger generation when he arrived, he took the initiative of addressing them directly, in particular by speaking Algerian dialect in speeches and interviews: as one, 14 years old in 1992, would remember, ‘he spoke the language of the people. You felt the Algerian in him … You felt you could trust this man – he was like us.’36 There was a feeling, among many who had opposed both the FIS and the generals’ coup, that Algeria might yet be saved from plunging into the abyss. Then, on 29 June 1992, Boudiaf was shot dead by one of his bodyguards while addressing a televised meeting in Annaba.

Figure 7.1 Mohamed Boudiaf, photographed on his return to Algeria from exile, 16 January 1992 (AP).

The Terror

The escalation of violence, already begun, now proceeded headlong. The FIS had been banned in March; in April the municipal and regional councils (APCs and APWs) that since June 1990 had been run by FIS-majority administrations were dissolved and replaced by appointed ‘Executive Municipal Delegations’ (DECs). On 15 July, the principal FIS leaders Abassi and Benhadj were sentenced to twelve years’ imprisonment by a military court at Blida. In the six months of Boudiaf’s Presidency, thousands of FIS militants had already been interned in detention camps in the Sahara. Others, radicalising the violence already practised by the movement in the 1980s, took to the maquis and launched an armed insurgency.

Islamists had occasionally physically attacked their political opponents before the elections. Tiny splinter groups calling themselves ‘Algerian Hizballah’ or Takfir wa’l-hijra, borrowing the name invented by the Egyptian government for the gama‘a islamiyya of the 1980s, already existed on the margins of the movement, and an armed attack at Guemmar, north of El Oued near the Tunisian border in November 1991, involved militants associated with the FIS-affiliated Islamist trade union, the SIT. In early 1992 armed militants engaged in sporadic clashes with soldiers and the police.37 In late 1990, veterans of Mustafa Bouyali’s mid-1980s insurgency, led by an ex-soldier, ‘General’ Abdelkader Chebouti, constituted guerilla groups in the Atlas south of Blida and resurrected the MIA. While, by agreement with the FIS, abstaining from obstructing the electoral process which they opposed in principle, Chebouti’s militia gained considerable prestige among FIS sympathisers for their more uncompromising posture. After the coup they emerged as the principal armed Islamist opposition movement, thought to number 2,000 fighters already in 1992, and engaged in low-level attacks on regime targets and security forces. An alternative strategy was followed by another group, FIS founder member and Afghanistan veteran Saïd Mekhloufi’s MEI (Mouvement pour l’état islamique). Mekhloufi had been head of security for the FIS before being removed from the party’s leadership ‘consultative council’ (majlis al-shura) at its emergency conference in Batna in July 1991. Declaring that ‘injustice arises and endures mainly because of the docility and silence of the majority’, he called for civil disobedience and hoped to create a ‘popular Islamist army’ – failing which, the MEI began to turn its violence on ‘recalcitrants’ among the people, hoping to provoke the radicalisation and inspire the loyalty that the ALN had achieved during the war of independence.38

These groups inherited a stock of ideas and images, a diffuse political imagination, from the war of independence, and a sense of continuity with the radicalism of earlier Islamist activism that had espoused violence as both justified and efficacious in the 1970s and 1980s.39 Among peri-urban populations that had moved from the countryside during the war or since independence, they also tapped into the long-standing mythology of the social bandit, the avenging outcast of the mountains, that had persisted through the colonial period and was still celebrated in popular culture – by the mid-1980s, among other media, on TV and in cartoon strip books that retold stories like that of Mas‘ud Ben Zelmat for a new generation, as well as in oral storytelling. Many FIS activists previously committed, whether on principle or by calculation, to constitutional politics, but who were now faced with the ‘theft’ of their electoral victory, undoubtedly gravitated towards armed struggle. At the same time, some of those who in previous decades had been student radicals, involved in violence against ‘apostate’ professors or ‘immodest’ women and committed to a radical vision of an Islamic state, had stood aside from the FIS, and now opted to pursue social and political regeneration without recourse to arms. Abdallah Djaballah, who had been a militant law student at the University of Constantine in the mid-1970s and by 1992 had become one of the most followed preachers in the Constantinois, in 1990 created a Harakat al-nahda ’l-islamiyya (Islamic Renaissance Movement, MNI) which preached ‘reconciliation’ instead of armed struggle and opted to work within the scope allowed by the system.40

These groups were not motivated by any unified, atavistic ‘imaginary’ (let alone the libidinal ‘violent pulsions’ that, recycling colonial-era psychology, some commentary on the war would evoke41). Rather, international circumstances and experiences or inspiration from elsewhere – most notably, the anti-Soviet jihad in Afghanistan – as well as the domestic situation and the internal diversity of the Islamist movement itself directed different individuals and groups into different avenues of action. The regime’s careful opening of managed, oppositional political space for some groups and co-optation of others, combined with ruthless repression and covert ‘management by violence’ of both the jihadist fringe and the broader social base that had propelled the FIS towards power, did the rest. Djaballah’s Nahda and Mahfoud Nahnah’s HAMAS, a political party created on the basis of his irshad wa ’l-islah society, were less populist, more cautious than the FIS, although sharing most of its views and its aspiration to create a ‘truly Islamic’ society and state. Electorally marginalised in the FIS’s brief high tide, they survived the subsequent crash and became part of the re-institutionalised political landscape.

While largely retaining the same rhetoric, HAMAS (which tellingly amended its name in 1997, without needing to change its acronym, from ‘Movement for an Islamic Society’ to ‘Movement of Society for Peace’) would opt for an entryist strategy, working in coalition with the recuperated FLN and regime party the RND in the late 1990s, while Djaballah’s various parties would maintain a more oppositional stance. The more intellectually inclined, non-violent Islamic reformism of the PRA (Party for Algerian Renewal), founded by disciples of Bennabi, sought to revive and apply his ideas. Rejecting the salafist notion that society must be ‘re-Islamised’, and drawing on Max Weber as well as Bennabi, they saw the challenge instead as being to revive Islamic ‘authenticity’ as a total social ethic that would become socially and economically ‘efficacious’. The party, under its founder Noureddine Boukrouh, faded into obscurity and compromise with the system, but some of its original adherents – who, while referring to communists, for example, as ‘those who had gone out of the community’, nonetheless rejected the label ‘Islamist’ and were sometimes themselves vigorously opposed to the FIS – continued to re-publish Bennabi’s works and to work quietly to disseminate their views.42

While these more quietist trends took different paths, the militant edge of the Islamist movement escalated its jihad against taghut, the ‘tyrannical’ regime, and those who supported it – and the regime escalated its violence too. On the night of 9–10 February 1992, as the state of emergency came into force, six young policemen (all were between 26 and 31 years old), most of whom were fathers of young children, were gunned down on the rue Bouzrina in the Casbah, signalling the beginning of terrorist action.43 The first major attack on civilians, a bomb blast at Algiers airport on 26 August 1992, killed nine people and injured 128. Condemned by an FIS publication, it was then attributed to a group of FIS militants, who for their part claimed that their confessions had been forced from them under torture.44 Attacks on infrastructure, security forces and state targets like members of the DECs, but also on journalists, academics and intellectuals, foreigners (including Algerians’ foreign spouses), working women and ‘immodest’ girls in public places, multiplied in 1993 and especially from the beginning of 1994. During the worst period of assassinations against writers and cultural figures, one Algiers journalist did not leave his apartment for three months; his wife had to ‘take care of everything’ and his children were told to tell everyone that they had not seen their father, and did not know where he had gone. Another journalist told his spouse and children never to show any sign that they recognised him if they saw him out of doors.45 In 1994, while attempting to reintroduce some degree of a ‘culture of dialogue’ into Algerian life and remind people what Algerian culture was capable of – notably by bringing the celebrated singer Warda al-Jaza’iriyya from Egypt to perform in the country that claimed her – as Minister of Culture Slimane Chikh, the son of national poet Mufdi Zakarya, ‘spent [his] time accompanying friends to the cemetery.’46 The wave of murders of prominent writers and artists forced many of Algeria’s cultural producers into exile in France, Europe or North America; ironically, while at home Algerians felt cut off and left to their fate by the rest of the world, these same years saw the beginning of a new global recognition of Algerian culture, especially in music and literature.

But international attention was focused mostly on the increasingly dark drama of the war. In the summer of 1992, a nebulous organisation calling itself the Jama‘a al-islamiyya ’l-musallaha (Islamic Armed Group, GIA), allegedly an umbrella organisation of Islamist guerilla units, emerged. ‘The’ GIA was not one group, but many. Pretending to hegemony over the insurgency and ostensibly espousing a more radical line on both the overthrow of the state – rather than simply re-instituting the FIS as a legal political force, which seemed to have become the ostensible short-term war aim of the MIA – and on the forcible Islamisation of society as a whole, the GIA was also a supple and decentralised organisation. Its label, look (‘Afghan’ style, with beards, shaved heads, turbans and loose-fitting clothing instead of the MIA and MEI’s stolen army uniforms) and style of unbridled, extreme and demonstrative violence could be ‘franchised’ by any local leader with a following. Paradoxically, the avowedly uncompromising aims announced by the GIA facilitated the adoption of its name and style by a plethora of new ‘military entrepreneurs’ who had much more limited and local objectives.47 Without any identifiable, concrete political agenda or real overall command structure to follow, pursuit of ‘total’ war against the local embodiment of taghut – policemen and their families, local authorities, existing networks of influence and property – became means of seizing control over local revenue and commerce and of establishing social precedence in particular districts that became the fiefs of (often short-lived) ‘emirs’. Ambitious local actors could reinvent both their ‘moral’ profile and their material fortune in the vacuum left by the removal of the FIS’s local government and the withdrawal of the state.

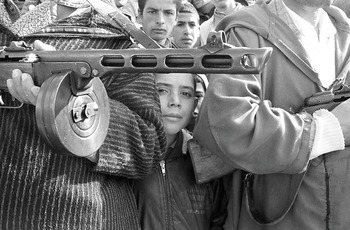

In the economically ravaged and roiling housing estates of the Algiers suburbs, especially, unemployed young men whose occupation, with wry Algerian humour, was said to be that of hittistes, ‘the men who hold up the walls’ (by leaning against them all day long for lack of anything else to do), often saw either the ostensible higher cause or, perhaps more often, the economic opportunities combined with the dark glamour of the GIA maquisards as irresistibly appealing.48 Local gangsters like Amar Yacine, known as ‘Napoli’ (supposedly from his desire to make enough money to go live there), in the upper Casbah, Beaufraisier, Eucalyptus, Baraki and other districts of Algiers, ran autonomous armed groups in which ‘jihad’ against the police was indistinguishable from a racketeering spree. In many places, local logics and interests, and a ‘privatisation’ as well as a generalisation of violence, were undoubtedly more immediately relevant causal factors of the spread and entrenchment of the war than either Islamist utopia or regime repression alone. If jihadi Islamism and anti-Islamist ‘patriotism’ often provided languages for expressing such interests, the regime also facilitated this degeneration into violence. In many districts where the FIS had enjoyed strong popular support in 1990–91, an apparent strategy of deliberate neglect of law and order enforcement by the authorities tacitly encouraged generalised insecurity. ‘There are thieves everywhere’, said an unemployed young graduate of his Algiers suburb in 1993, ‘ … it’s normal now, there are no more police officers, you have to fend for yourself, the thieves are getting rich … The government, they did this on purpose, I promise you.’49 This picture of life in Algeria after 1992 – thieves getting rich everywhere, generalised insecurity, a state the population cannot trust and which acts ‘on purpose’ against them, the need for everyone to fend for themselves – would come to be very widely shared, and would persist over the following decade. In Algerian vernacular, the very word normal (used in French whatever language is being spoken) came to designate, with unsurprised, cynical irony, the perfect banality of life in a permanent state of crisis and collapse.

The fluidity and multiplicity of the GIA made the group especially hard to pin down and suppress, as did the frequent succession of its commanding ‘emirs’: Mohammed Allal (‘Moh Léveilley’), the leader of the rue Bouzrina attack who was killed in August 1992; Abdelhak Layada, arrested in Morocco in June 1993 and released from prison in 2006; Djaafar ‘el-Afghani’, killed in February 1994; Chérif Gousmi, killed in September 1994; Djamel ‘Zitouni’, killed in July 1996; Antar Zouabri, killed in February 2002; and Hassan Hattab, who left the organisation in 1996 to found a splinter group, the GSPC, and disappeared, having apparently surrendered to the authorities, after 2007. But conversely, the same characteristics also suggested its malleability and liability to manipulation. The GIA was very soon suspected by some of being, if not a network of ‘pseudo-gangs’ or counter-guerillas directly organised by the DRS, at least heavily infiltrated and manipulated by them to split the insurgency and sow confusion in its ranks, taking the counter-insurgency into the maquis to provoke war between Islamist factions – which by the summer of 1994 the GIA had largely done – and more generally discredit the cause of other ‘true mujahidin’ and terrorise the population by spectacular atrocities against civilians. Thus began the vexing question of qui tue?

The emergence of the GIA, its escalation of violence and high media profile and its rapid eclipse of the earlier movements, MEI and MIA, were countered to some degree by the appearance in July 1994 of an Islamic Salvation Army (Armée islamique du salut, AIS), which under a ‘national emir’, Madani Mezrag, declared its loyalty to the imprisoned FIS leadership. Political figures claiming continuity with the FIS had already radicalised their own tone so as not to be outflanked. A 19 March 1993 FIS communiqué signed by Abderrezak Redjam, the FIS’s underground communications chief inside Algeria, affirmed that ‘what is occurring is not terrorism, but a blessed jihad whose legitimacy arises from the obligation to create an Islamic state, and [in response to] the coup d’état against the choice of the people … The criminal junta must stand down so that Algeria can devote itself to rebuilding what they have destroyed by theft, despotism and Westernisation.’50 Anwar Haddam, a nuclear engineer elected to parliament for the FIS from Tlemcen in December 1991 and now in asylum in the United States, where he styled himself the head of a FIS ‘Parliamentary Delegation’ in Europe and the USA, described the assassination of psychiatry professor Mahfoudh Boucebci, outside his hospital in June 1993, as ‘not a crime but a sentence carried out by the mujahidin.’51 When a massive car bomb claimed by the GIA exploded on 30 January 1995 near the central police station on the boulevard Amirouche in downtown Algiers, as a packed bus was passing, killing 42 people and injuring 286, Haddam justified the attack, describing the death toll as an ‘unfortunate’ accident of timing.52

Rivalries, personal or political or both, between the factions spread, and Islamist leaders and others involved in attempts at brokering negotiations with them were assassinated – Kasdi Merbah in August 1993, Abdelkader Hachani in November 1999. Accusations that assassinations and atrocities officially imputed to the GIA were in fact carried out by disguised army units, or directed by security operatives in the maquis, multiplied in the media, particularly in France and the wider Algerian diaspora, and circulated widely on the internet. Within Algeria, such uncertainty, and a generalised climate of suspicion and insecurity, only added to the fear stoked by ‘false roadblocks’ set up by guerillas in military uniform, where travellers were racketed or murdered, indiscriminate attacks on trains and buses, car bombs and attacks on individual civilians in towns, and the abduction and rape of young women in the countryside. Uncertainty about who ‘the terrorists’ really were was expressed in divergent ways: among young conscripts within the army, it was apparently said (repeating a long-standing trope of Islamic martyrology) that the corpses of mujahidin found in the mountains did not decay and smelled of musk.53 At the same time, more prosaically, the word tango came to be a widespread derogatory term for Islamists, apparently referring to the radio moniker in use in the police (‘T’ for terroristes): later, the term acquired a delicious irony appreciated by drinkers when Tango, manufactured in Rouiba, near Algiers, by the millionaire businessman Djilali Mehri, became Algeria’s leading brand of beer.

If martyrology and cynical humour both helped Algerians to put the horror escalating around them into more manageable terms, both the extent of the horror and the stakes involved in accounting for it reached a peak between 1996 and 1998. On the night of 26–27 March 1996, seven Cistercian monks, all French nationals, were abducted from the monastery of Notre Dame de l’Atlas at Tibhirine, high in the mountains just outside Medéa. The monks’ long-standing medical mission to the local population was combined with a deep personal and institutional commitment to remaining in Algeria, a commitment they shared with many other clergymen and – women of the Catholic church who had come since independence both to minister to the small remaining European population and to sustain a dialogue of prayer and spiritual exchange with Muslim interlocutors. They had repeatedly refused to leave.54 On 30 May, their heads were found, without their bodies, near Medéa. The brothers’ kidnapping had been claimed in a GIA communiqué on 26 April, and another, dated 23 May, announced that they had been killed, their throats slit, two days earlier. But doubts emerged almost at once: the authorities ineptly attempted to conceal the absence of the monks’ bodies, which were never found, and it appeared that the victims had been decapitated post-mortem, disguising the cause of death. Claims abounded that the ‘GIA’ operation attributed to Djamel Zitouni was in fact a deliberate manipulation by the DRS to implicate the Islamists in an act of ‘barbarity’, remove the monks (whose determined presence in a highly insecure zone and, worse, their readiness to provide medical care to all comers, including guerillas, was irritating) and shock French opinion into firmer support for the regime. An alternative scenario, published in the Italian daily La Stampa in 2008, later suggested that the monks had been inadvertently killed by machine-gun fire from army helicopters attacking the Islamist camp where they were being held.55 The truth remained inaccessible after twenty years of speculation and occasional pressure on the Algerian authorities: the only clear outcome was the horror of the act, the only indubitable fact the unaccountability of those behind it.

Both the most spectacular and the most bitterly disputed acts of violence were yet to come. In the early hours of 29 August 1997, a massacre of civilians at Raïs, a neighbourhood on the eastern edge of Sidi Moussa in the Mitidja twenty kilometres southeast of Algiers, killed at least 98, and perhaps as many as 300 people: men, women and children were all killed, often with knives and axes, or burned to death. In a carnage that (no doubt deliberately) both recalled and exceeded the worst terror of the war of independence, bodies were mutilated, eviscerated and displayed in the street, heads left on doorsteps. Several young women were abducted by the attackers. The Raïs murders were followed by a spate of mass killings in the Beni Messous district on the outskirts of Algiers to the north, and in the Mitidja again, at Bentalha, near Baraki, a few kilometres north of Sidi Moussa, on 23 September, in which perhaps 250 people were killed. Subsequent massacres, especially in the west of the country in villages around Tiaret and Relizane between December 1997 and April 1998, were thought to have taken up to 400 or 500 lives in single episodes. At the end of 1997, in the first two weeks of Ramadan alone, over 1,000 people were killed in Algeria.56

The several hours’ duration of these massacres, the non-intervention of nearby army and police forces – or even their alleged complicity in sealing off areas under attack – and the apparently ‘false beards’ of the attackers, cast doubts on official claims that the atrocities were perpetrated solely by Islamist militia attempting to destabilise the state. Combined with the geography and timing of the violence, which struck especially at former FIS strongholds that had provided material aid to guerillas, and occurred as legislative, local and senatorial elections were being held (in June, October and December 1997), such doubts suggested that, whether committed by ‘real’ GIA militia that had been infiltrated and instrumentalised by the DRS or by covert army death squads only masquerading as Islamists, the massacres were outward effects of factional conflict within the regime.57 Others insisted that the bloodbaths were more simply the desperate acts of Islamist extremists whose expected victory over the regime had not materialised, and who found themselves increasingly under pressure from the army, without a realisable war aim, losing support among the population and vengeful against those who, having formerly aided them, had recently stopped supporting their struggle. Whatever the truth, whether intended by elements of the regime to demonstrate that Islamism was beyond the pale and had to be ‘eradicated’, or by Islamists to demonstrate the lengths to which they would go if pushed, or both, the latter turned to its own purposes by the former, the massacres were clearly intended as an obscenely exemplary spectacle, a theatre of cruelty that horrified ordinary Algerians and played to all the worst imaginings of international opinion and the global media.

The butchery à l’arme blanche, especially the murders and mutilations of mothers and children, recalled and exorbitantly magnified, in entirely incomparable circumstances, the ritualistic peasant violence of anti-colonial insurrection. The open perpetration of atrocity and the elements of display – bodies, or heads, exhibited in the street or on doorsteps – recalled the colonial practice of leaving the bodies of ALN junud or suspected sympathisers in village squares and roadways. The particular, grisly details narrated after the fact – such as the claim that attackers at Bentalha had made bets among themselves on the gender of unborn babies before disembowelling pregnant women – directly echoed tropes of the ‘increasingly explicit violence’ that had characterised commemorative narratives of the war of liberation since the early 1980s, in contrast to the relative circumspection of earlier publicly aired accounts of the war.58 Such acts were less evidence of an unconscious ‘return of the repressed’ in a traumatised ‘national psyche’ than calculated mises en scène, a surely deliberate and targeted staging of well-known scripts that had been fed into society and socialisation over the previous fifteen years. As optimism about the revolution’s prospects faded, such narratives had increasingly shaped a culture of national memory that emphasised both the glorification of armed struggle and the dehumanising extremes of victimhood.59

Commentators, especially in France, where in the mid-1990s debates about the war of independence were resurfacing in both academic and political life, began to refer to the violence as a ‘second Algerian war’, sometimes with the implication that this new violence had arisen from the ‘unhealed wounds’ of the older struggle. Within Algeria, language and imagery drawing on the war of 1954–62 was indeed used by all sides to claim credentials and to deny legitimacy to others, and in some areas the conflict must have been structured around local social and generational tensions, as it had been during the war of independence. Citizen militia officially called ‘self-defence groups’ (groupes de légitime défense, GLDs) were thus universally known as patriotes and, in many rural areas, were first constituted by the older generation of ALN veterans, supported by the National Organisation of Mujahidin (ONM). At the same time, the Islamist guerillas claimed the mantle of ‘true’ mujahidin for themselves, and while they denounced their enemies as hizb fransa, they were themselves accused of being ‘the sons of harkis’.60 Whether or not some insurgents were in fact the offspring of formerly caïdal or harki families, seeking to regain the property or redeem the social status lost since independence, was in this respect beside the point, since it was the moral charge, not the material accusation, that really mattered, although in some cases the latter might also have been true. Again, rather than simply, compulsively re-enacting the revolution, these narratives were both a means of conflict, staking claims in a ‘moral economy’ that was effective because shared throughout society, and a means of rationalising and recounting what was otherwise fast becoming, not – by any means – something ‘innate’ to all Algerians, but on the contrary horribly foreign and incomprehensible to the vast majority of them.

Whoever was responsible for the wave of massacres that engulfed Algeria in 1997–98 before subsiding into smaller and less frequent, though still persistent, incidents of violence in the following years, there could be no doubt at all that elsewhere, state terror was in full swing. In the escalating struggle to suppress the insurgency and terrorise, in turn, its civilian supporters, from 1992 onwards thousands of suspects ‘disappeared’ into undocumented detention, where torture by the security services was once again both routine and extreme. Many people – the number, inevitably, being impossible to calculate – never re-emerged. Ever since the war of independence, the torture of suspects had been part of the secret services’ regular functions: used against actual or suspected opponents under Ben Bella and Boumediene, and against detainees in October 1988, it was now once more employed on a massive scale – with beatings, electricity, water, electric irons, drills, and soldering tools, blowtorches, rape – in police stations and DRS holding centres across the country.61 In early 1992, Mohamed Lamari took charge of a combined, multi-service counter-terrorist operation involving the army, gendarmerie and police. His counterpart, the other (unrelated) Lamari, General ‘Smaïn’ of the DRS, from his office in the Directorate of Counter-Intelligence and Internal Security, took charge of more covert aspects of the counter-guerilla. Among the regular arms of the security services, many police officers saw themselves simply as combating a terrorist threat to their country. Regular policemen accustomed to walking the beat or doing traffic duty volunteered for the new, special anti-terrorist police, the BMPJ; dressed in black, armed with Kalashnikovs and wearing balaclavas during operations, they resembled they army’s special intervention units, and like them became known as ‘ninjas’. Some, appalled by what they were told to do and later seeking asylum in Europe, would tell horrific stories of torture and of DRS collusion in assassinations and massacres. Others, either uninvolved in the violence of interrogation and intimidation or judging it justified in the struggle against the terrorism that was killing their comrades and relatives, drew satisfaction from their role in winning the war.62

As the violence escalated, it also became diffused, dividing families, urban districts and villages across the country. Relatively inaccessible rural areas, vulnerable country roads and settlements, became virtual no-go zones where the state ceased to have any regular presence: police and soldiers sheltered in heavily fortified barracks, and insurgent bands operated with apparent impunity. In the absence of any more formal rule of law, some of the ‘self-defence groups’ (GLDs) that the government began to arm in 1994 as counter-insurgent militia would also, like the insurgent armed groups, be accused by human rights observers of carrying out extrajudicial killings, acts of terror and involvement in local vendettas. The privatisation of violence and its multiple local logics became divorced from the ostensible conflict of Islamists versus government, and fed on local ‘war economies’, through which local, private or sectional interests and the local networks of the state, whether in competition or in collusion, came to have greater stakes in the perpetuation of the conflict than in its resolution.

In 1992–93, belief was strong among young Islamist sympathisers in the imminent collapse of the regime and the victory of Chebouti, ‘the lion of the mountain’ and his avenging army: in the words of a newspaper-seller in the Algiers suburbs, ‘It won’t last, Chebouti, he’ll come down from the mountain with his mujahidin and I promise you, he’ll kill the lot of them’.63 But it did last. Boudiaf’s murder itself, committed by a lone gunman, Lembarek Boumaarafi – a sub-lieutenant in a police special intervention unit who was known to have Islamist sympathies and who had unaccountably been placed, against protocol, in Boudiaf’s bodyguard on the day he was killed – was at once widely, and soon almost universally, seen as having been ordered by the hard men of the pouvoir who had quickly regretted their choice of president and had no intention of allowing him to undermine or bypass them.64 On the surface a shocking sign of the fragility of the state even at its highest level, from this perspective the assassination of Boudiaf already displayed the resilience of the system at the centre of the state, its determination to defend itself and the complete absence of any ‘red lines’ it might hesitate to cross. In 1992–95, the HCE’s regime slowly regained ground against the insurgency, averted what its supporters saw as a threatened ‘collapse of the state’ after Boudiaf’s death and could claim to have ‘saved Algeria from the débâcle’ that faced it in 1992.65 The HCE’s supporters would also point out that, as rarely occurs in such circumstances, it respected the anticipated end of its mandate, dissolving itself at the end of 1994 and appointing General Liamine Zeroual, a 53-year-old ex-maquisard from Batna who in July 1993 had succeeded Nezzar as defence minister, as State President for a three-year ‘transitional period’.

While the state may have been close to collapse in the immediate crisis of 1992–94, the regime’s hard core had now regained the initiative. The men who removed Chadli were sufficiently determined to fight an all-out, and atrocious, war against the Islamist insurgents, and entrenched enough either to co-opt or to sideline their opponents in the political class. An attempt at a negotiated political solution among the opposition parties, put together during talks brokered by the Catholic community of Sant’Egidio near Rome in November 1994 and announced in a platform ‘for a peaceful resolution’ to the crisis in January 1995, was rejected outright by the regime. Most of the platform’s proponents were ignored: the external leadership of the FIS, whose political re-entry was anathema to the décideurs, Ben Bella’s MDA and the FFS and al-Nahda, which remained opposition movements. The PT was persuaded back into line. Honest opponents of the Rome initiative judged it ‘inopportune’, since as they (and many in Algeria, long allergic to ‘intrusions’ into national sovereignty) saw it, any initiative to reach out to the Islamists and resolve the crisis needed to come from within Algeria, not from outside.66 For others, the reopening of political dialogue simply had to be sabotaged. Abd al-Hamid Mehri, who signed the Sant’Egidio platform for the FLN, was soon taking calls from his central committee colleagues who, they told him, could no longer support the initiative, having been ‘put before difficult, and sometimes extreme, choices’.67

It was therefore somewhat surprising when, in February 1995, Zeroual renewed the regime’s own attempts to engage a ‘national dialogue’ that, he said, was the only solution to the crisis and must include ‘the participation of the national political and social forces without exception.’68 Presidential elections in November 1995 confirmed Zeroual in office, and a constitutional revision a year later strengthened the Presidency’s powers, particularly by establishing an upper chamber, the Council of the Nation (informally known as the ‘senate’), one-third of whose members would be designated by the President, and allowing the President to legislate by decree whenever parliament was not in session. At the same time, an important progressive counterweight was introduced in the limitation of a President’s mandates to a maximum of two five-year terms, suggesting both the strengthening of the Presidency and the potential for it to become a more fully ‘constitutional’ office.69 New legislative, regional and local elections in June and October 1997 were won overall by Zeroual’s newly created party, the RND. Accusations of fraud and ballot-rigging were widespread, but the undoubtedly calculated distribution of kursis had the effect of parcelling out representation tolerably across the political spectrum. The ‘moderate’ Islamist parties, Hamas and al-Nahda, now sat in the national assembly alongside the FLN and representatives of other shades of opinion prepared to accept entry into the system under the regime’s rules.70 A wider political dialogue also seemed possible. As Minister of Defence in Redha Malek’s government, Zeroual had already pressed for negotiations with Abbasi and Benhadj: Malek had dismissed the idea as ‘a waste of time’.71 Now, feelers were put out to the imprisoned FIS leaders.

But Zeroual’s ‘national dialogue’, while no doubt intended, among other aims, to marginalise Sant’Egidio, was nonetheless opposed by the ‘eradicators’ in the regime. His loyal lieutenant and ally, the former DGDS chief General Mohamed Betchine, was systematically undermined and discredited by a vitriolic press campaign that revealed the extent of his suspiciously accumulated private wealth. The ANP moderniser Mustafa Belloucif, who had seemingly made the same wrong enemies some years earlier, had already been thrown to the media as a scapegoat for corruption in April 1992. As under Chadli in the early 1980s, such selective and suspiciously timed corruption investigations served particular political interests much more than public justice and accountability. And just as it seemed that the earlier stage of the insurgency was being brought under control – in January 1996, eleven founder members of the FIS called for a ceasefire, the curfew in urban areas that had confined families to their overcrowded apartments every evening for three years was lifted in February, and government spokesmen began to speak of ‘residual’ terrorism – the violence suddenly multiplied and intensified. The abduction at Tibhirine came just as Zeroual prepared to meet the signatories to the Sant’Egidio statement; after Abdelkader Hachani and Abbasi Madani were conditionally released from prison in July 1997, the wave of massacres of civilians began in earnest.72 Where some saw GIA extremists resorting to ever more brutal tactics to stop the return to elections and eliminate the possibility of dialogue with the regime by their rivals of the ex-FIS, others saw a clear campaign by the ‘eradicators’, through Tewfik and Lamari in the DRS and their agents in the GIA, to undermine Zeroual and force him out. He held on for another year, until 11 September 1998, when in a surprise TV address to the nation barely two years into his term of office, the President announced his intention to cut it short. New presidential elections were to be held in April 1999.

After the War

Although it would flare sporadically for several years still, the violence began to abate. Without any real political or social resolution of the conflict, after seven years of war the Islamist insurgency was effectively exhausted, and society politically demobilised and desperate for a return to normality. The basic elements of the regime – the army and security services, the factional interests and patronage networks of their bosses, and the institutions of the state around them – were firmly restored to power. Observers abroad debated the nature of the violence and the utility of calling it a ‘civil war’, often, once again, in ways that mostly annoyed Algerians while adding little to anyone else’s understanding of what had been happening to them. The generalisation of violence, the arming of society between Islamists, GLDs, police and the military, with familial survival strategies often – anecdotally, but no doubt on a large scale – involving one son joining the police and another the ‘mujahidin’, the neighbourhood denunciations and the intimacy of violence in the worst-affected areas, the extent of both popular alienation from the security forces and, elsewhere, of popular resistance to the armed Islamists, certainly made the struggle a civil war in the sense that the armed conflict was not simply between clearly demarcated camps of insurgents and government, but turned society in on and against itself.

At the same time, the ‘classic’ developments often thought characteristic of civil wars did not materialise: the state’s institutions, especially the army and police, did not collapse or split, large areas of national territory were never effectively occupied and fought over for any length of time by rival protagonists, and above all, the general population was not mobilised politically in support of one or another clearly distinguished armed force carrying rival political projects.73