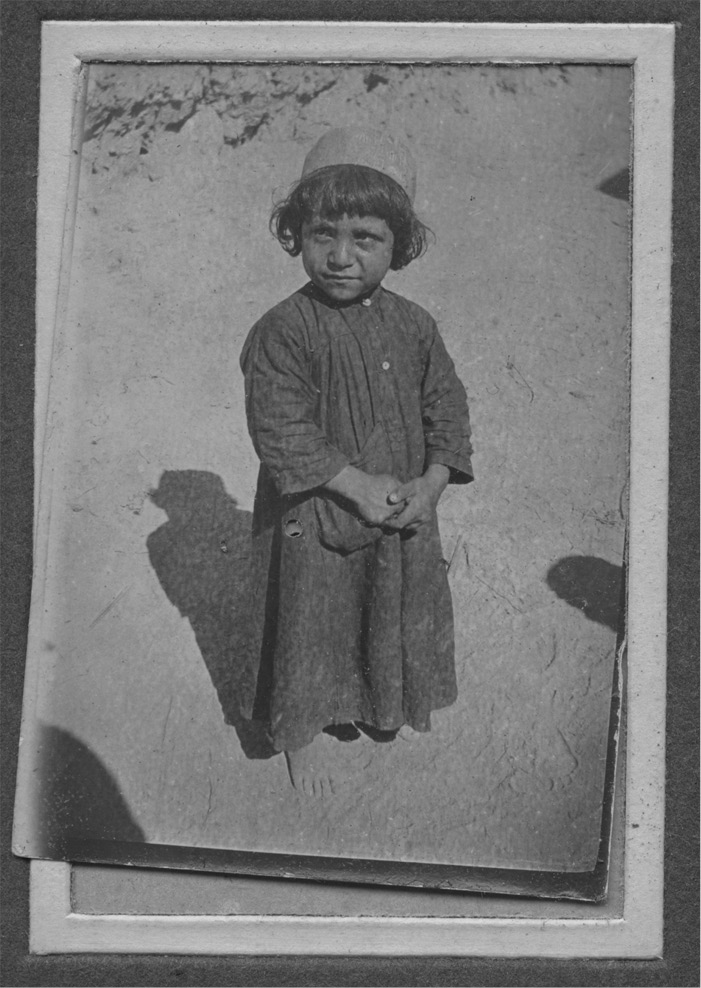

Framed by the sun stands a small Arab girl, unadorned and alone, in a slightly frayed thwab and sporting a tarboosh (Figure 6.1).Footnote 1 Remarkably composed, even slightly quizzical, for someone so young, she stands her ground, with the right foot thrust forward, hands firmly clasped together and the face slightly askance.Footnote 2 The punctum, one may say, lies in the unsmiling eyes and mouth as they hold the camera’s gaze at an angle. The effect is rare. Curiosity, suspicion, trepidation, war-weariness: it is difficult to read the expression but child-like delight or ease is not one of them. It is the knowing look of someone much older than her years. The photograph would have been striking even in the collection of Ariel Varges, but what makes it remarkable is that I came across it in the ‘war album’ of Captain Dr Manindranath Das, mentioned in the Introduction, who served as a doctor in Mesopotamia in 1916–1918. We know very little about his war experiences, except that he was a distinguished doctor, and that he pretended to be dead and stayed behind to treat wounded soldiers when others had retreated after an attack. He risked his own life to bandage their wounds, for which he was given the Military Cross.Footnote 3 Family lore has it that he would have got the Victoria Cross, had he been white. But we know hardly anything beyond these details. The story is typical of how little is known of the experiences of the participants of the Mesopotamia campaign, even when the subjects were educated, articulate and decorated.

Figure 6.1 An Arab girl wearing a thwab and a tarboosh, photographed somewhere in Mesopotamia by Captain Dr Manindranath Das.

For the Indians, Mesopotamia was the main ground of battle: the largest number of Indians – some 588,717, including 7,812 officers, 287,753 other ranks and 293,152 non-combatants (often forming porter and labour corps) – served there between 1914 and 1918.Footnote 4 The campaign, which was managed by the Government of India rather than the War Office in London, was a classic example of the colonial government’s Macbeth-like ‘vaulting ambition which o’erleaps itself/And falls on the other’. What began as a limited defensive operation in 1914 to protect the oilfields of Abadan and pre-empt any serious jihadi threat evolved in 1915 into a full-fledged offensive to capture Baghdad, and resulted in what is often considered the British Army’s greatest humiliation in the First World War. In a campaign marked by dust, disease and death, the biggest debacle was the five-month-long siege in the city of Kut-al-Amara (7 December 1915–29 April 1916), and two years of abject degradation for the non-officer prisoners of war, both British and Indian, who would be dragged across Iraq, Greater Syria and Turkey. At the time of surrender, the number of Indians captured was around 10,440, including 204 officers, 6,988 rank and file and 3,248 camp followers.Footnote 5 While we have British POW first-person accounts, there have been no corresponding Indian accounts. Instead, the much publicised photograph of a sepoy in an advanced state of starvation fills that silence with horror (Figure 6.2). Part of the aim of this chapter is to break this deafening silence around the Indian experience in Mesopotamia through the investigation of freshly unearthed material.

Figure 6.2 An Indian POW, in an advanced stage of starvation, recently freed after the Siege of Kut in Mesopotamia, 1916 during an exchange of prisoners.

In her powerful study A Land of Aching Hearts: The Middle East in the Great War (2014), Leila Fawaz notes that ‘World War I was not only a global event, but also a personal story that varied across the broad Middle East.’Footnote 6 If experiences in the Middle East, like the campaign itself, long remained marginalised, the stories of the British POWs as well as of the local men and women from Iraq, Lebanon and Turkey are being increasingly heard and examined.Footnote 7 While there has been some work on the military logistics of the Indian army in Mesopotamia, the actual experiences of the men have remained unknown. In recent years, the novelist Amitav Ghosh has powerfully drawn attention to this area through his remarkable blogposts.Footnote 8 What I wish to recover and examine here are the ‘personal stories’ of the men from the Indian subcontinent as well as how such stories intersected with those of their allies and enemies across the broad Middle East over the four years. While discussing ‘cosmopolitan thought-zones’, the political historian Kris Manjapra makes the following observation:

To frame the global circulation of ideas within the lone axis of centre versus periphery is to view the world through the colonial state’s eyes and through its archive. As theorists of interregional and transnational studies have pointed out, the practice of taking sideways glances towards ‘lateral networks’ that transgressed the colonial duality is the best way to disrupt the hemispheric myth that the globe was congenitally divided into an East and West, and that ideas were exchanged across that fault line alone.Footnote 9

The South Asian war experience in the Middle East provides a singular vantage-point for examining such ‘lateral’ encounters: what we have in this extraordinarily cosmopolitan theatre is a multi-ethnic, multi-lingual and multi-religious army from British India interacting with people from a vaster but similarly multi-ethnic, multi-lingual and multi-religious empire at a time when the strains of the war effort had started triggering the genocide of the Ottoman Armenians. The plural identities of the Indians – as invaders, victims, fellow colonial-subjects and often co-religionists (for the Muslim sepoys) – interacted with an internally divided local population, often defying any neat political, racial or religious grid. What drives the present chapter, among other issues, are the testimonial, affective and intimate dimensions of these encounters between Indians, both sepoys and educated medics, and a range of Ottoman subjects in several contexts: occupation, combat, siege and captivity.

The military campaign remained the backbone for cultural encounters.Footnote 10 On 6 November 1914, the Sixth Indian (Poona) Division crossed over the bar of the Shatt al-Arab into Turkish waters, captured the Ottoman fort at Fao and headed towards Basra; by the end of the month, it had captured the city. Having tasted easy success, the ambitious cavalry-officer General Nixon, Commander of the IEF ‘D’, craved for more. ‘Having swallowed Basra and retained it in the face of Ottoman counter-attack’, as Leila Fawaz notes wryly, ‘fanciful aspirations of sacking the minarets of Baghdad, glittering some five hundred miles upstream, appeared as enticing as a Mesopotamian mirage.’Footnote 11 The responsibility fell on General Charles Townshend, the commander of the Sixth Division. In May 1915, Townshend continued his offensive up the Tigris towards Amara aboard HMS Espiegle and then HMS Comet; his men, known as Townshend’s ‘Regatta’, got onto small local boats called bellums to chase through weeds and marshes a retreating Ottoman army. By September 1915, the British flag flew over Basra, Amara, Qurna, Nasiriyah and Kut. Townshend continued his unstoppable advance towards Baghdad but, on 22 November, the whole show came to an abrupt halt: his exhausted and malnourished army faced a numerically superior, well-camouflaged and entrenched Turkish army at Ctesiphon. In the ensuing battle, the Indian casualties were enormous, estimated at 4,300. Townshend now retreated to Kut, expecting reinforcements and hoping to regroup over the winter; instead, he would be faced with one of the longest sieges in British history.Footnote 12 There were several significant but unsuccessful attempts to relieve the town, first by Lieutenant-General Aylmer in March and then by Captain Gorringe twice in April.Footnote 13 Townshend finally surrendered on 29 April 1916. While the captured officers received preferential treatment, the privates, both British and Indians, suffered ‘two years of horror’.Footnote 14 After the fall of Kut, the campaign was rethought and the control passed from India to Britain. Under General Maude, the British forces advanced carefully up both sides of the Tigris, occupied Kut in December, and finally entered Baghdad on 11 March. Throughout the campaign, religion was often a flash-point. As early as 14 November 1914, the Sheikh-un-Islam, on behalf of the Caliphate, had declared a jihad or holy war against the British and French empires and promised the Muslims who supported them ‘the fire of hell’.Footnote 15 Even though the colonial government repeatedly reassured the Muslim sepoys that the ‘holy places of Islam’ would be protected, there was consternation; for example, the 15th Lancers refused to open fire on their Turkish co-religionists in Basra in 1915 with the whole regiment ‘taking an oath not to fight against Muslims’.Footnote 16

What were the ‘undertones’ of such an arduous campaign and what are our sources? British memoirs provide tantalising glimpses, from accounts of men ‘going mad in the heat’ and ‘dancing in no man’s land’ to Major Carter’s famous account of a hospital ship bringing Indians covered in their own faeces after the battle of Ctesiphon.Footnote 17 Indian testimonies on the Mesopotamia campaign are very rare, as we have nothing similar to the archive of censored Indian mail from France. While it is possible to recover the activities of the relief forces from the substantial visual archives and the unit diaries, the most ‘silent’ of the fronts in the campaign is the world of siege and captivity: there have so far been no POW diaries or letters or memoirs from the Indians. This chapter recovers and examines this shadowy world through freshly unearthed and unusual material – the writings (in Bengali) of a group of educated and largely middle-class Bengali men who served as medical personnel – doctors, orderlies, stretcher-bearers and clerks. Their value is two-fold. First, if Indian testimonies have largely been sepoy-centric, here we have the voices of non-combatants. Coming out of a more educated milieu as well as being acutely conscious of the historical importance of the experience, several of these men wrote memoirs.Footnote 18 Second, we have here for the first time glimpses into life under captivity. Starting with the initial impressions of the occupied land and its people through these memoirs as well as the few extant sepoy letters, I shall then examine Indian experiences and encounters in the context of combat, siege and captivity largely through the lens of two extraordinary testimonies – a set of letters by Dr Kalyan Kumar Mukherji and a 209-page-long memoir Abhi Le Baghdad by Sisir Prasad Sarbadhikari. I shall read them alongside the writings of their friends and colleagues as well as those of British prisoners in Mesopotamia.Footnote 19

Between the Primitive and the Familiar: Basra, Bazaars and Boodhus

Orientalism, mythic history and muddy reality jostled together in British soldiers’ first impressions of Mesopotamia: space was perceived as deep time. If an ‘Arabian Nights’ quality hung over the desert air in the north, the British soldiers knew that the country ‘spanned the whole land of Holy Writ, from Jerusalem to Babylon and from Babylon to Shush’.Footnote 20 The British traveller D. G. Hogarth anticipated the responses of the Tommies by some ten years when he noted, in 1904, that travelling in Mesopotamia was ‘to pass through the shadow of what has been’: the cradle of civilisation was now a forsaken land.Footnote 21 Depopulation, disrepair and dereliction had set in over the centuries and Mesopotamia, as the soldiers found it in 1914, was alternately a desert and a swamp. Every spring, water would stream down the Taurus and Zagros mountains and flood the low-lying land, with its innumerable creeks, canals and ditches, and the sand would morph into mud.Footnote 22 If the mud on the Western front was the product of industrial artillery, the British soldiers saw the mudflats in Mesopotamia as the natural habitat for the so-called ‘primitive people’ of ‘Turkish Arabia’: ‘It is a mud plain so flat that a single heron, reposing on one leg beside some rare trickle of water in a ditch, looks as tall as a wireless aerial. From this plain rise villages of mud and cities of mud. The rivers flow with liquid mud. The air is composed of mud refined into a gas. The people are mud-coloured.’Footnote 23 Did the Indians too see the land and its people through a similar lens – myth-fringed but mud-splattered?

Orientals are often most prone to Orientalism. On reaching Basra, Dr Kalyan Mukherji wrote to his mother: ‘Ahre Ram, is this the Basra of Khalif Haroun al-Rashid? Chi! Chi! There is not even the faintest sign of roses; instead what we have here is a 10–12-hand-long, 5–6-hand-wide and 20–21-hand-deep ditch. Into it flows the water of the Tigris, knee-deep or waist-deep. Each of these ditches is home to at least two hundred thousand frogs – small, big and medium-sized. Most of them are bull-frogs. What a terrible din they make.’Footnote 24 The language of the land which housed the Tower of Babel seemed to have degenerated into a cacophony of frogs but the spry Orientalist humour is free of any racialising discourse. Mukherji was stationed just outside Basra; the account of his fellow Bengali Ashutosh Roy of the actual city was different:

The town reminds me of our own towns. The shops are well-decorated. The bazaar is covered … At the entrance of the canal that leads from Shat-el-Arab to Basra is another bazaar, called ‘Ashar’. The well-to-do live around here and the bazaar is not small. The canals and the rivers are full of boats called ‘Mahellas’ – they are like the ones we have back at home (‘chip naukār mato’) but smaller. They are good for fast travel. Most well-to-do people have their own mahellas. At every lane here, you will find ‘Kāwākhānā’ or Coffee-shops; they can be compared to the street-side tea-shops in our country. The big difference is that in our country, only in the morning and in the evening, people crowd around these places to have tea; but here are crowds of coffee-drinkers at all times of the day.Footnote 25

Neither the fantasy-town of Haroun al-Rashid nor the site of dereliction as in British accounts, Basra emerges here as bustling, stratified, familiar. While we have photographs of ‘Ashar’ bazaar from the British travel-writer Gertrude Bell, Roy records its daily rhythm: Arabs and Armenians having bread with meat for lunch and drinking coffee or performances by Bedouin street-dancers. The streetscape of Al-Qurna reminds him of his own native Varanasi; he also records the Ottoman army in retreat and a Turkish cruiser on fire. A seasoned traveller who had previously written an account of his travels in China, Roy mixes travelogue, ethnology and military expedition in his account, which was serialised in a Bengali journal and illustrated with photographs.

The accounts of Kalyan Mukherji and Ashutosh Roy are exceptional. The authors were educated, middle-class and culturally confident, and there is a close engagement with the land, its people and its history which is absent from the few sepoy-letters we have from Mesopotamia. But their gaze, like that of the British travellers, is often ethnological: the Arabs are described as sturdy and bold but ‘lazy’, while the Armenians are depicted as intelligent, good-looking, well-dressed (‘their food, manners, and dress are far superior to the Turks’), but somewhat cowardly and untrustworthy.Footnote 26 As Roy enters Al-Qurna, ‘the Garden of Eden’, a rogue Armenian interpreter points to ‘the tree of knowledge’; a sceptical Ray notes, with wry humour, ‘Whatever the truth, all I can say is that the mosquitoes of this place are beyond description – a suitable place indeed for our ancient father and mother.’Footnote 27 However, the real objects of his fascination as well as of racist opprobrium are the Bedouins or ‘Boodhus’: ‘They are uncivilized. They eke out a living through looting and plunder. They also try to earn a livelihood by raising sheep, goat, bulls, camels, horses and donkeys. They have no fixed address – they pitch big blankets like tents and live at one place for two to three months … The Boodhus are very fierce. They do not hesitate to kill people even without proper reason.’Footnote 28 Such comments are echoed in other accounts; the diary of the 47th Sikhs refers to them as a ‘treacherous and thieving race, whose habit it is to appear to side with the stronger party … Boodhus, flies and dust are the plaguers of the country’, while there are references in both British and Indian memoirs to their alleged habits of looting and massacring people.Footnote 29 But Roy is fascinated: he lingers on, and photographs their gestures, clothes and ornaments, not just reminiscent of British travellers in Mesopotamia, but bearing traces of Kaye and Watson’s ethnological project Peoples of India. Ethnology did not act solely on an East–West axis, nor was it just a racial science. Class, as much as race, underpinned these ethnological forays; if the British colonials had photographed ‘primitive’ Indians, Roy in turn draws on an ethnological vocabulary to understand the Bedouins.

Such engagements with the locals, ethnological or otherwise, are absent in the handful of letters from sepoys in Mesopotamia that have survived by dint of being written to their friends serving in France. Though these letters are from soldiers involved in the relief efforts of 1916–1917, they are revealing of the general sepoy attitude towards Mesopotamia, particularly in the light of our discussion in the last chapter:

The country in which we are encamped is an extremely bad place. There are continual storms and the cold is very great, and in the wet season it is intensely hot … If I had only gone to France, I could have been with you and seen men of all kinds. We have all got to die someday, but at any rate we would have had a good time there.Footnote 30

You know very well that I am not in India. I am with Force ‘D’. You must know very well where Force ‘D’ is. Since coming here I have met many men who were formerly in France. From them we have heard all about France. In truth, you must be very comfortable there, since the ‘public’ there is so civilised, and money too is plentiful. The particular part of the world where I am is a strange place. The seasons here are quite different from what you experience anywhere else. We have already experience of the cold and wet. Now the heat is threatening us from afar. It rains very heavily and the entire surface of the land becomes a quagmire … Except for the barren, naked plain, there is nothing to see.Footnote 31

Experienced or imagined, France is the yard-stick and the obscure object of desire: the difference between France and Mesopotamia, according to another sepoy, is that ‘between heaven and earth’.Footnote 32 If the sepoy letters describing France are often rhapsodic, leading Markovits to call them ‘Occidentalism from below’,Footnote 33 the descriptions here are unremittingly negative. Mesopotamia confronted the sepoys with an underdeveloped version of their own country: ‘uninhabited’, ‘desolate’ and ‘barren’ are recurrent words used to describe the landscape.

Priya Sathia has argued that, after the horrors of industrial combat on the Western Front, British war officials made the mission of ‘developing Iraq’ into a key site for the ‘redemption of empire and technology’, a point we briefly touched upon in Chapter 3.Footnote 34 As early as 1916, Edmund Candler had noted that a military infrastructure – the construction of roads, bridges, dams – was cast as a way of ‘bringing new life to Mesopotamia’ at a time when ‘the war had let loose destruction in Europe’.Footnote 35 The main agents in such technological rejuvenation of Mesopotamia were the British Indian army – its labourers, sappers, miners, engineers, signallers – as photographs portrayed them engaged in a wide variety of roles: building bridges and dams, chlorinating water at an advanced post (Figure 6.3), laying telephone cables, working at a slipway near the Shatt al-Arab waterway or fixing signalling posts, or driving a tractor to haul a howitzer across the Diala. While such activities were woven into an imperial narrative of Britannia bringing progress and development to Mesopotamia through the work of another colonised race, i.e. the Indians, the actual labourers who were doing the hard work were less impressed. Being the orderlies of both war and empire, they had neither the imperial guilt nor the humanistic angst of men such as Candler and expressed their opinions bluntly. The harsh climate, the rickety infrastructure and the meagre provisions fuelled discontent: ‘They do not give us postcards to write. In France there was no lack of anything. It has remained for us to encounter the greatest of difficulties in this place. There is no sign of milk or sugar, and for drink, we have nothing but the water of the Djlah.’Footnote 36 While it is possible to partly reconstruct the later years of the campaign through an interweaving of the army unit diaries, occasional letters and photographs, we know very little about the Indian experience during the early years, particularly during the siege or under captivity. It is in this context that we now turn to Kalyan Mukherji’s letters and Sarbadhikari’s memoir.

Figure 6.3 Indian army engaged in chlorinating water at an advanced post in Mesopotamia, 1917.

Kalyāṇ-Pradīp: Politics, Protest and Mourning

Kalyāṇ-Pradīp is as unique a document in the history of South Asian literature as it is in the literary history of the First World War. A 429-page-long memoir, it was written by an eighty-year-old widow, Mokkhada Devi, as a tribute to her thirty-four-year-old grandson Kalyan Mukherji who died as a POW in Mesopotamia.Footnote 37 Kalyāṇ-Pradīp – literally meaning Kalyan-Lamp – was written to keep alive the ‘flame’ of his memory. Mukherjee was born into an upper-middle-class family in Calcutta, and trained as a doctor in Calcutta, London and Liverpool before joining the prestigious Indian Medical Services (I.M.S.). In the memoir, Devi closely follows the arc of Kalyan’s life, from his time in Calcutta and England to the outbreak of the war and his service in Mesopotamia until his death on 18 March 1917; framing the life-story is a vivid re-imagining of the Mesopotamia campaign with a degree of familiarity with operational details which is astonishing for an eighty-year-old woman in Calcutta. Amidst her account, set like jewels, are Mukherji’s own letters from various battle zones, and under siege and in captivity, to his mother. Blurring the boundaries between Bengali home front and Middle Eastern war front, Kalyāṇ-Pradīp is as much a first-hand testimony to the campaign in Mesopotamia as it is to how the war was being understood, remembered and re-imagined in colonial Calcutta.Footnote 38

Mukherji’s wartime missives are exceptional in at least two respects. First, for once, they are complete and original rather than censored and translated fragments that we have in the case of sepoys from the Western Front. Second, Mukherji’s are the only letters from an Indian that cover two full years of the war on any front, from the time of his arrival in Basra in April 1915 until his death on 18 March 1917. Equally remarkable are the sophistication of his sensibility and its evolution as, Owen-like, he bears testimony to front-line horrors and turns them into the vale of soul-making. Attached to the Ambulance Corps of the 6th Division, he bore first-hand witness to the battle of Amarah in June 1915 and then the battle of Nasiriyah on 25 July, where he managed a dressing station behind an orchard-wall 300 yards behind the trenches. Missives from the front, his letters – like those of his British colleagues in the Western front – are acute sensory palimpsests, resonant with the ‘shai-shai’ of rifle-fire, the ‘boom-boom’ of artillery or the description of the shrapnel spreading like ‘a shower of hail-stones against the sky, as if an invisible hand from the sky is throwing a handful of pebbles’ (314). These letters can be compared, across the imperial divide, with the letters of fellow non-combatant and officer Spink who arrived in Basra at a similar time, witnessed the same battles, experienced the siege and captivity and wrote at length to his parents. Thus, after the battle of Nasiriyah (25 July), Spink wrote to his father about the ‘big show’ and stated that ‘we whacked them once again’,Footnote 39 but, for Mukherji, it became a turning point towards disenchantment:

At five in the morning, we left the camp with bandages, medicines, iodine, milk and brandy in order to take care of the wounded. From 5 pm our cannons started.

Boom! Boom! roared around twenty or twenty-five cannons at once. After fifteen or twenty minutes, our soldiers began to advance from behind us firing above our heads like hail-stones … After two or three hours, unable to bear the bombardment any more, the enemy started to retreat … Around 3 pm, a group of prisoners and some of the wounded enemy soldiers began to arrive. From 6.30 in the morning till 1 pm, I did not have time even to breathe. Rivers of blood, red in colour – everywhere – I was covered in blood. Whom to nurse first? Like Dhruva in ‘Immersion’, I wondered, ‘Why is there so much blood?’ Why such bloodshed? What more can I describe? I shall never forget such a scene in my life.Footnote 40

His documentation fast devolved into acute soul-searching and critique: ‘What I have seen – it is impossible to describe. Today the English flag has been flown here.’Footnote 41 The juxtaposition is telling: the ‘English’ flag, though secured through Indian sepoys, brings no sense of pride. Throughout his letters, the campaign, like the victory above, is referred to as ‘English’, never as ‘ours’.

Kalyan’s letters provide vivid snapshots of the offensive, from Nasiriyah in July and Kut in September, when he spent three days in the trenches and was commended by Nixon for ‘collecting the wounded from a shell-swept area’ (423). Their documentary value, singular as it is, is outweighed for the reader by the tumultuous world of feeling that the letters record following Townshend’s advance from Nasiriyah to Kut-al-Amara. His growing sense of disenchantment was perhaps a direct response to the change in the nature of the campaign from a defensive expedition to one of aggressive offensive action, spurred by the ambition of Townshend and Nixon: ‘I understand that we won’t advance any more. But then I have heard that so many times.’ Later, from Aziziyah, sixty miles upriver from Kut: ‘We have advanced a lot – why more? It is us, having tasted victory, who are snatching away everything from the enemies; the enemies have not yet done anything.’Footnote 42

On reaching Aziziyah on 3 October after the victory at Kut, an anxious Townshend asked for an order ‘in writing over Sir J. N.’s signature’ about the viability of a further advance and received an immediate order to ‘open the way to Baghdad’.Footnote 43 In sharp contrast, Mukherji was rent apart by conflict. In quick succession, he wrote to his mother, first from Kut on 4 October:

I have had my fill of warfare. I have no more desire to see the wounded and the dead.

Rows and rows of injured men are being sent by ships, belonging to us or the Turks, to Amara. Many of them will be going to Bengal Ambulance. Some have lost a hand, some a leg – everyone is asking for water. And still men continue speak about the glory of war and try to prove its advantages. In the name of patriotism and nationalism, they go on to cut each other’s throats. There is nothing as narrow-minded as nationalism in this world … If the word ‘patriotism’ (or ‘nationalism’) did not exist in the European dictionary, there would have been far less bloodshed.

In our country too, in the name of patriotism, many leaders are teaching small schoolchildren how to kill. Murder, the greatest sin, becomes morally acceptable when committed in the name of patriotism. If a person, by guile or force, takes away another’s property, it is burglary or dacoity – again a sin. But when a nation snatches away another’s land – then it is celebrated as empire. Well, there’s little point in discussing all this now – just hope that the war ends soon.Footnote 44

and then again on 20 October:

Great Britain is the teacher. The patriotism the English have taught us, the patriotism that all civilised nations celebrate – that same patriotism is at the root of this bloodshed. All this patriotism – it means snatching away another’s land. In this way, patriotism leads to empire-building. To show the love of one’s country or race by killing thousands and thousands of people and grabbing someone else’s land, well, that’s what the English have taught us.

The youths of our country, seeing this, have started to practise this brutal form of nationalism. Therefore, the random killing of people, throwing bombs at a blameless Viceroy – all these horrific things, they have started. Shame on patriotism. As long as this parochialism does not end, bloodshed in the name of patriotism will not cease. Whether a man throws a bomb from the roof-top or fifty men start firing a cannon – the cause of this bloodshed, this madness is the same.Footnote 45

The level of intellectual maturity and anti-war fervour are reminiscent of the letters of war poets such as Owen and Sassoon. His letters are very different, however: they are not just condemnations of violence or narrow patriotism, as in the trench-letters of Owen and Sassoon, but complex reflections on the relationship between war, empire and nation. Mukherji’s radicalism is two-fold. As a colonial subject, he exposes the intimate relationship between war and imperialism. However, his anti-colonial critique, even as he acknowledges the deep educational influence of England upon the Indian bourgeoisie, cannot be equated with Indian nationalism. Through acute reasoning, he associates imperial aggression with its obverse – nationalist terrorism. For Mukherji, imperialism, revolutionary nationalism and the European war were all implicated in the same vicious cycle of violence, reminding one of the similarly anti-colonial and anti-nationalist stance of Rabindranath Tagore who was writing his novel Ghaire Baire (The Home and the World) – a critique at once of imperialism and nationalism – the very same year.

Mukherji sustained a slight injury in the battle of Ctesiphon on 25 November but, brushing aside a generous offer to take leave, he accompanied 400 injured soldiers on a steamer to Kut-al-Amara. At Kut he became part of the besieged 6th Division and, after the surrender on 29 April, he was taken captive. He bore traumatised testimony to the siege, which we will discuss later in relation to Sarbadhikari. Being an officer, he was treated relatively well after the surrender and was allowed to write home at least once a month. His are so far the only letters we have from among the 10,000 Indians besieged at Kut. In The Secret Battle: Emotional Survival in the Great War (2010), Michael Roper has discussed how soldiers wrote obsessively to their mothers; elsewhere, I have written about the importance of the mother’s kiss in the trenches.Footnote 46 Mukherji’s letters, written under captivity, are similarly beset by his longing for and anxiety about his ageing mother: ‘Please don’t catch your death by worrying about me … I want to see you when I come back.’Footnote 47 With almost Sophoclean irony, this was the time when Mukherji, in Ras al-‘Ain, received a letter about the sudden death of his daughter and his mother’s grave illness. He immediately wrote back to his mother:

Ma, please take care of yourself, please get well. I want to see you so very much – I shall come home soon! Please don’t leave the world before I get back. I know my eldest daughter has died, but it is not the end of the world. You too lost your eldest daughter. When I come back home, I will have lots of children – so please don’t worry about that! I am desperate to hear your news, to read letters in your hand … When I read your voice, I feel very happy. Please don’t worry about me. I’m very well here but I’m always thinking and worrying about you.Footnote 48

Kipling’s fictional letter about the Indian soldier pining for his mother finds its eerie echo not in sepoy letters but in that of a middle-class Bengali doctor. Kalyan’s mother died in November, but he did not receive the news until 3 March 1917. Meanwhile, an epidemic had broken out in the camp, and he wrote in February 1917 that, ‘if people are not removed from here, no one will survive’ (416). This was to be his last letter.

His final days are pieced together by his grandmother from his friend and fellow captive Dr Puri, who remembered how Mukherji, on learning the news of his mother’s death, ‘lost all enthusiasm for life and his instinct for survival’: he could not eat or sleep, and started muttering ‘Oh dear, my goodness’. He soon came down with fever and became delirious on 12 March: ‘In his delirium, he would speak constantly in Bengali. The other doctors and I could not understand Bengali but we could clearly make out the words “Mother! Mother! Oh dear mother! What happened my mother!”’ After six days of delirium, he died on 18 March.’Footnote 49 The grandmother was sent back Kalyan’s belongings: his horse’s saddle, his reins, watch, shoes, clothes and bags. To read the last few pages of Kalyāṇ-Pradīp is to listen to a threnody of loss and mourning: Kalyan’s mother mourning the death of her grand-daughter; Kalyan mourning the death of his mother and daughter; Dr Puri mourning the death of his friend (‘Kalyan laid me on his breast and saved my life, but I could not save him’)Footnote 50 and, above all, an eighty-year-old woman – the author – mourning the death of three generations: Kalyan’s mother, Kalyan and Kalyan’s young daughter. In Kalyāṇ-Pradīp, Mesopotamian history evolves into mourning diary without a break or mediating pause.

Abhi Le Baghdad: Battlefield Trauma, Hunger at Kut and the March

Sisir Prasad Sarbadhikari’s Abhi Le Baghdad (1957) begins where Mukherji’s letters end. While Mukherji’s letters become sparse after the debacle at Ctesiphon, Sarbadhikari’s 209-page-long memoir evokes in harrowing detail the battle itself, the resultant siege and life under captivity. Mukherji and Sarbadhikari were fellow Bengalis in Calcutta (Sarbadhikari in fact refers to Mukherji) but, as an elite medical officer and an Indian orderly, their experiences were markedly different. As are the tone and genre. Mukherji’s letters are missives from the front, blending vivid snapshots with acute reflections; Sarbadhikari’s book is a memoir sui generis, reading in turns like battlefield notes, nursing memoir, POW diary and travel narrative. It is possibly the most powerful and sustained piece of Indian life-writing to have emerged so far from the war.

Abhi Le Baghdad is alone of its kind: there seems to be no precedent for it in the annals of Indian literature. Paradoxically, Sarbadhikari’s literary cousins would be Remarque and Blunden from across the racial divide. Written with the same combination of immediacy, literariness and anti-war fervour, Abhi Le Baghdad is All Quiet on the Western Front turned upside down – from a non-combatant, non-white and non-Western Front perspective. The title is revealing: it does not flaunt its historical authenticity, such as E. O. Mouseley’s Secrets of a Kuttie: An Authentic Story of Kut (1921), nor is it an exercise in self-aggrandisement, such as postal officer Kunal Sen’s Through War, Rebellion & Riot 1914–1921. Instead, it is taken from the bitter aside of an anonymous Muslim soldier during the retreat to Kut: ‘Ya Allah, abhi le Baghdad’ (‘Oh Allah, so much for taking Baghdad’). The whole memoir, similarly, is a view ‘from below’ or, as his fellow captive the British NCO P. W. Long named his memoir, Other Ranks of Kut (1925). It is written in Bengali, but, as in many such books by the educated Bengali middle-classes, it shows intimate familiarity with English literature and frequently refers to it, from the Scottish song ‘Auld Lang Syne’ to Oliver Goldsmith’s ‘The Deserted Village’.

Sarbadhikari had just completed a degree in law when the war was declared. He volunteered as a private in the newly formed ‘Bengal Ambulance Corps’ (BAC) for Mesopotamia primarily because of, in his own words (in English), a ‘spirit of adventure’.Footnote 51 The Corps comprised four British commissioned officers, three Viceroy’s Commissioned Officers (VCOs), sixty-four Non-commisioned Officers (NCOs) and privates (including Sisir) and forty-one camp followers, including cooks, water-carriers and cleaners. They reached Amara on 15 July and set up the Bengal Stationary Hospital in Amara where they were stationed for the first two and half months.Footnote 52 In September, some thirty-six of them, including Sarbadhikari, were chosen to be sent to the firing line as part of the 12th Field Ambulance of the 16th Brigade. The story centres around this group of idealistic Bengali youths as they encounter the battle of Ctesiphon (November 1915), the resultant siege of Kut (December 1915–29 April 1916) and captivity for the next two years. As a medical orderly who knew English and picked up Turkish, Sarbadhikari was made to work in hospitals in Ras al-‘Ain and Aleppo, and then in the German camp at Nisibin. The memoir is closely based on his wartime diary, which has its own tale of trauma and survival to tell:

It would be a mistake to believe that the diary I have maintained till now or what follows is the original version. After surrendering at Kut, I had torn up the pages of the diary and stuffed the pieces in my boots; I had written a new version at Baghdad from the remnants. This copy, too, was spoilt when we walked across the Tigris – although the writing was not rubbed off entirely since I had used copying pencil. I kept notes about the Samarra–Ras-el-Ain march and onwards in that copy itself, after I dried it. I had to bury the copy for a few days at Ras-el-Ain but not much harm had been done as a result. I copied the whole thing again in the Khastakhana at Aleppo. (156–157)

The diary travelled with him to Calcutta and was converted into a memoir with the help of his late daughter-in-law Romola Sarbadhikari, a remarkable woman, with whom I had a series of interviews, from 2007 to 2010. Since my discovery of this privately printed text in 2006, it has become better-known, thanks largely to the brilliant blogposts of Amitav Ghosh, who has called its survival ‘insistently miraculous’ and notes its ‘extraordinary immediacy’: ‘at times, the book has the quality of a diary’.Footnote 53

Such diary-like immediacy is evident in Sarbadhikari’s description of the battle of Ctesiphon (22 November 1916) where he accompanied the army as part of the Field Ambulance. It was his first proper taste of combat: ‘As we kept advancing, bullets were whizzing above our heads and cannon balls exploding noisily behind us.’ (35). His colleague Prafulla Chandra Sen distinguishes, in his reminiscence, between the different sounds on the battlefield: the ‘miao’ sound of the .303 British bullets, the ‘bumblebee-like buzzing’ (‘bhramarer guñjan’) of the bullets fired by the Arab soldiers and the ‘hiss’ of shells.Footnote 54 Sarbadhikari instead focussed on the aftermath of the attack as the next day dawned:

Ctesiphon – the second of the two days.

It is beyond my power to describe what I witnessed as the 23rd dawned. The corpses of men and animals were strewn everywhere. Sometimes the bodies lay tangled up; sometimes wounded men lay trapped and groaning beneath the carcasses of animals. The highest death toll was in the front of the trenches where there were barbed wire fences. In places there were men stuck in the barbed wire and hanging; some (fortunately) dead and some still living. There might be a severed head stuck in the wire here, perhaps a leg there. A person was hanging spread-eagled from the wire – his innards were spilling from his body. There were spots within the trenches where four or five men were lying dead in heaps; Turks, Hindustanis, British, Gurkhas – all alike and indistinguishable in death.

‘In a death embrace

Grasping each other by the neck

Lay the twain’ … [Original in English]

We saw a Sikh sitting and grinning by himself in one place – his teeth bright in the middle of his black beard. I wondered what the matter was with him – how could he be laughing at a time like this? I went close to him and realised that he had long since been dead. Perhaps he had grimaced in his death-throes.

It fell to me and Phani Ghose to note down the names and numbers of the wounded. And what a task it was! (42–43)

‘If I live a hundred years, I shall never forget that night bivouac’, Charles Townshend would write in his memoir.Footnote 55 Sarbadhikari not only had to count the wounded but also had to disentangle the living from the dead and arrange the wounded ‘with their own haversacks under their heads and a blanket to cover them’ (40); Prafulla Sen, working alongside him, remembered the eerie silence: ‘Some have had their whole rib-cage shattered, some had lost their jaws but there was hardly any sound.’ But the most difficult part for the two Bengali boys was having to show empty bottles to British Tommies who were crying for ‘a drop of water for heaven’s sake’ or having to leave the seriously injured to be collected later: ‘This terrible chill on top of the injuries – many died of the cold itself.’Footnote 56

How does Sarbadhikari remember and represent the scene? In The Great Push (1917), Patrick MacGill, an Irish stretcher-bearer on the Western Front, notes that ‘The stretcher-bearer sees all the horror of war written in blood and tears on the shell-riven battlefield. The wounded man – thank heaven! – has only his pain to endure.’ On the other hand, the French novelist Henri Barbusse in Le Feu (1916) concludes his harrowing description of the battlefield with the image of a German and French soldier in death-embrace.Footnote 57 Sarbadhikari combines the visual testimony of MacGill with the anti-war critique of Barbusse: his account moves from the optical rectitude of ‘severed head’ and ‘innards’ through the macabre multiculturalism of the battlefields to focus on the single Sikh soldier who blurs the boundaries between life and death, laughter and grimace. Combining testimony, reportage and exposure of the horrors of war, such visceral description is the Indian counterpoint to Robert Graves’s ‘dead Boche’, ‘Dribbling black blood from nose and beard’.Footnote 58 If theories of trauma dwell on gaps in consciousness, the First World War accounts circle round visceral memories. Sarbadhikari’s memoir is no exception: he describes how he woke up to find himself lying next to a corpse; in Basra, he witnessed a shell explode within the makeshift tented hospital in a garden, ‘taking off half the face of a sepoy lying in the hospital tent. There was nothing left of his face – blood was gushing from a gaping hole where his mouth, nose and eyes had been’ (66). Like Owen drenched in the blood of his ‘poor little servant George’, Sarbadhikari could easily have said ‘My senses are charred.’Footnote 59

Yet, such extremity also produces rare moments of intimacy. Sarbadhikari mentions how his colleague Bhupen Banerjee took off his ‘British warmer’ and gave it to a British casualty; Sen, in his account of the night, remembered a young English captain, who had lost part of his leg, gazing forlornly on the cross that hung from his neck: ‘As we [members of the BAC] gave him some water and saluted him before lifting him on to the stretcher, he gave us a wan smile which, even after eight years, I remember clearly.’Footnote 60 In one of his letters, Dr Kalyan Mukherji mentions a very similar episode. On his way from Ali Gharbi to Sannaiyat, he encountered a severely wounded British soldier; as he poured some water into his mouth, the latter tried to kiss Mukherji’s feet and tears rolled down his cheeks, and, as Kalyan took him in his arms, he died.Footnote 61 Records of such intimate moments, particularly across the colour-line, are very rare in Indian accounts and here form the real-life counterpart to Grimshaw’s fantasised death-embrace between the English officer and the dying Beji Singh; however rare they were, Mukherji’s account shows that moments of touch and intimacy were by no means restricted to the Western front or between European comrades alone. Neither Sen nor Sarbadhikari mentions nursing the enemy, though that does not mean that they did not do so. A number of images have recently surfaced which show officers from the Royal Army Medical Corps, along with Indian medical orderlies and stretcher-bearers, tending to wounded Turkish soldiers at an advanced dressing station in Tikrit in November 1917. One shows the Turks laid out in rows on stretchers, with the sun beating down, and Indian and British medical personnel at work; another shows a Turk sprawled on the ground, with two Indian medical orderlies poring over him (Figure 6.4). Though they were taken within the context of professional duty, these photographs, like the nursing memoirs by British women, suggest spaces of contingent contact between men across the political lines.

Figure 6.4 A Royal Army Medical Corps officer and some Indian staff tending to wounded Turks at an advanced dressing station after the action at Tikrit, November 1917.

Map 6.1 Hand-drawn map of Mesopotamia, with place names in Bengali, showing the sites of the Battle of Ctesiphon, the siege of Kut, and finally the route of the brutal desert march Sarbadhikari would be forced to undertake in 1916. Included in Abhi Le Baghdad.

Much ink has been spilt over Charles Townshend’s decision to retreat from Kut after the Battle of Ctesiphon.Footnote 62 For over 140 days, the SixthDivision was besieged in Kut. He laid the blame on the ‘dejected, spiritless and pessimistic’ sepoys: ‘How easy the defence of Kut would have been had my division been an all British one instead of a composite one.’Footnote 63 Since he was an educated medical orderly, Sarbadhikari’s experiences were perhaps not typical, but his is so far the fullest account of life inside the town. He initially worked in a makeshift tented hospital set up in a date-orchard, on the outskirts of the city, which was regularly bombed. Several patients and BAC workers were killed or injured; Sarbadhikari was then transferred to the British General Hospital, but movement across the city was difficult, with regular bombings and air-raids which killed the native Arabs as well. Through gradual details, he builds up a picture of life in Kut: the regular round of injuries, British planes dropping a few paltry bags of wheat flour, the daily fluctuations of hope around Aylmer’s Relief Force, the big but unsuccessful push to capture Kut on 24 December, the diminishing stock of food and medicine, and the ‘perennial hankering for something sweet’ (85).

‘Hunger’, Townshend wrote to his Turkish counterpart, ‘forces me to surrender.’Footnote 64 Much of the discussion around Kut had revolved around the question of horsemeat. Faced with dwindling supplies, Townshend prescribed horsemeat for the men, only to be faced with rebellion en masse by the sepoys (except for the Gurkhas). The entry in Sarbadhikari’s diary for 28 January reads as follows: ‘Horseflesh started being served today onwards. Most of the Indian sepoys, Hindu and Muslim, did not eat it. We had it. The meat was very tough.’ (72). April was the cruellest month. In mid-April, after the 13th Division’s failed attack on Sannaiyat, an increasingly anxious Townshend cut down the rations from 10 to 5 ounces of attah (whole wheat flour), with the sepoys getting only ‘the sweepings, full of husk and dirt and mouldy’.Footnote 65 Starved and hungry, 5,000 sepoys on 11 April finally accepted horsemeat, though the remaining half still refused; on 12 April, a desperate Townshend threatened to demote non-meat eaters, both officers and NCOs, from their ranks and, by 14 April, most of them were taking horsemeat. But it was too late. According to Colonel Patrick Hehir, the chief medical officer in Kut, ‘on an average fifteen men were dying daily: of these, five a day were dying of chronic starvation and ten with chronic starvation with diarrhoea, bronchitis or some other simple malady supervening’.Footnote 66 Hehir, in his account, did not distinguish between British and Indian troops; in The Siege of Kut-al-Amara (2014), Nikolas Gardner mentions a study that apparently indicates that ‘the number of Indians who died from disease and starvation inside Kut exceeded the number of British personnel by ten times’.Footnote 67 Sarbadhikari’s evocation of the final month is remarkable, from his detailed account of how the BAC members burnt dung cakes and horse-bones to cook horsemeat and their efforts to ward off scurvy by picking leaves, grass and weeds, to descriptions of how the ‘healthy frames’ of the sepoys gradually became ‘skeletal’ (85). Desertions increased too, for which he blamed hunger, rather than religion. He mentions a young boy from the 19th regiment who tried to desert but was caught and executed: ‘The firing party was formed from his own company – perhaps there were men from his village, perhaps even from his kin’ (83). The members of the BAC pulled through the crisis, though ‘their constant companion’ was hunger:

Even in the midst of these troubles the eighteen of us spent our days merry-making. There would be songs every evening. Our billet was like a small club. Sanyal Moshai from Supply and Transport, Ashu babu and Raj Bahadur-babu used to drop by whenever they had time. A havildar from 4th Rajputs attached to our No. 2 Field Ambulance was a daily visitor. A driver from the Artillery, Malaband, used to come often. He was very religious and was later driven insane and committed suicide. A few others were also driven to suicide at Kut. All of them had gone insane. (87)

Part of the achievement of Abhi Le Baghdad is the way it manages to be an ode to the spirit of human resilience and warmth and contact without sanitising any of the horrors. Friendship, fellow-feeling and the indomitable spirit of adda [chatter] co-exist with horror and insanity, but the balance gradually begins to tip. Kalyan Mukherji wrote in mid-April that ‘For the last fifteen days, people are starving to death. What is the use of medicine when there is no food? … How can I cure them when there is nothing to eat?’Footnote 68 On 28 April, Sarbadhikari wrote ‘Not a single grain of ration today’; the next day, Townshend surrendered.Footnote 69

If hunger was the predominant memory of the siege, the moment of horror in Abhi Le Baghdad was the forced march of the privates to Ras al-‘Ain via Bagdad and Mosul, under a blazing sun and on minimal rations and water. Many collapsed while marching and were left to die, and British accounts stress the gratuitous cruelty by both Arab and Turkish guards.Footnote 70 Heather Jones has pointed to the ‘dominant scandal’ around class: while the British and Indian officers were relatively well-treated and transported on steamers, the privates – both Indian and British – were forced on a 500-mile-long march.Footnote 71 In Other Ranks of Kut, P. W. Long, a private, has a whole chapter on ‘Horrors of the March’, which were for him ‘the tortures of the damned’: ‘Daylight came but still no water … I put one foot before the other like an automaton. My lips were hard and dry and my tongue was like a piece of leather.’Footnote 72 Long could complete the march only because he was given some boots by a kindly Havildar of the Mahratta regiment. Being a member of the BAC, Sarbadhikari was transported in a steamer from Kut to Baghdad, and from there was sent by train to Samarra, some sixty miles away.Footnote 73 From Samarra, he was made to march to Mosul via Tikrit and Sargat, and again from Mosul via Nisibin to Ras-al-Ain, where he arrived on 25 August: in total they had marched for 500 miles over forty-six days. (Figure 6.5) The march is the most traumatic episode in the whole memoir and is evoked with a sort of hallucinatory intensity:

This march under the torment of the guards, with starved, parched, exhausted bodies, crossing mile after mile of mountainous land or barren desert on foot, was horrifying – a nightmare never to be forgotten. I shall remember it forever.

See that White swaying over there? Catch hold of him now before he falls to the ground.

What is the matter with him? A sunstroke?

Whatever it might be, take him along with you somehow, he must not be left here.

You have not had anything to eat for four days? Cannot take another step?

There is no use saying that, you must march. The guards will not wait for you, nothing will sway their stony hearts.

You sold off your boots in Baghdad because you were starved. Your feet are bleeding, sore after walking barefoot over sand and stones and thorns, you are walking with strips of cloth tied around your feet …

Your chest is parched, your tongue is hanging out, you cannot speak from the thirst after walking since morning till noon. You keep seeing ‘buttermilk sherbat’ written on red cotton floating in front of your eyes, you cannot will it away however much you try.

That means that it is not too long before you go insane – even so, walk on you must. You cannot lie here. Surely you know what the consequences are of lying here alone? Dying bit by bit in the hands of the Bedouins.

There goes the scream of the guards ‘Haidi, iyalla!’ [‘Get up, get moving!’]

Those yells of ‘Haidi, iyalla!’ by which the guards drove us on are never to be forgotten. You would wake up with a start – are they not screaming ‘Haidi, haidi? No? Well, let us fall back asleep, then. (134–135)

Reminiscence, flashback, testimony and j’accuse are fused and confused as he refers to the march in the Bengali original as ‘bhayāvaha’ (‘horrifying’), ‘duḥsvapna’ (‘nighmar(ish)’) and ‘vibhīṣikā’ (‘terror’). The only other Indian record of a similar march appears in the reminiscence of fellow Bengali Shitanath Bhatta, of the Supply and Transport department of the 6th Division, who referred to the ordeal as ‘indescribable’.Footnote 74

Sarbadhikari’s account, in contrast, is strikingly vivid. Memory here is both the cutting-instrument and an open wound: he does not just remember but seems to relive the moment as he reverts to the present tense – the eternal now – of the trauma victim who, as Sigmund Freud noted with reference to the soldiers on the Western Front in Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920), is ‘doomed to a compulsion to repeat past experience as present’.Footnote 75 The string of rhetorical questions, often combining Bengali and English (‘Kī hoyeche or? Sunstroke?’) in the original, the sudden intrusion of second-person pronouns (Sarbadhikari uses the semi-formal ‘tomake’ and ‘tomar’), the regular addresses (‘tāke dharo’ - ‘please hold him’, ‘calte pārcho nā’ - ‘you can’t walk anymore’, ‘tomāke coltei hobe’ - ‘you have to walk’), the claim on the body – feet, tongue, chest – cancel the gap between the past and the present and draw in the reader. ‘All that long day’, notes Long, ‘the air resounded with “Yellah, haidi, goom, yellah, yellah’.Footnote 76 Bhatta too remembers such shouts, accompanied by beatings with whips, rifle-butts and shoes.Footnote 77 If Sarbadhikari and Bhatta dwell on the horrors, Long records an extraordinary act of friendship: ‘a sepoy, who had been helped for several miles, finally collapsed and could not rise again, not even when the Onbashi tried kicking him to his feet. He was a Hindu and a naik of his regiment pleaded to stay with him. But the request was denied and the man left to die.’Footnote 78 Bhatta attributes such cruelty specifically to the Turkish race, who, he claimed, have hearts ‘harder than stones’.Footnote 79 Such essentialist categories or racist discourse are wholly absent in Sarbadhikari’s account.

Cosmopolis in Extremis? Vulnerability, Empathy and Encounters

According to Major E. W. C. Sandes, ‘our Indian rank and file suffered severely it is true, but not to the extent of the British’.Footnote 80 This has led some historians, including Nikolas Gardner and Patrick Crowley in their otherwise excellent works, to conclude that ‘British personnel suffered even more acutely’.Footnote 81 It is true that, in captivity, 1,767 of the 2,949 British POWs died or remained untraced, compared with 3,032 dead or untraced among the 10,686 Indian captives.Footnote 82 But, in the absence of any detailed breakdown of a timeline for the casualties, Indian or British, it is impossible to say that the Indians suffered any less on the march itself.Footnote 83 Preferential treatment by the Turks towards the Indian Muslims started only at Ras al-‘Ain, where the Muslim troops were separated and sent to various camps in Turkey, while the Hindus and Sikhs were subjected to back-breaking labour at the Ras al-‘Ain railhead. British narratives of Ottoman captivity are crowded with the sight, sound and even festering touch of their Indian subjects–allies–fellow POWs. Long recalled how men working at the railhead resembled ‘animated skeletons hung about with filthy rags’; Captain Mouseley remembered how at night one heard ‘the high Indian wail’: ‘Margaya Sahib, Margaya’ [‘Dying, Sahib, I’m dying’]; Charles Barber, a doctor attached to the 6th Division, noted how, for these malnourished and overworked men, ‘large wounds would sometimes begin by showing promise of healing for a few days, but would then stop and progress no further; would bleed when touched’.Footnote 84

As a medical orderly with English and some Turkish, Sarbadhikari was more fortunate. He worked for a couple of months in a makeshift hospital in a Bedouin tent at Ras al-‘Ain, then for more than a year at the Central Hospital in Aleppo and finally in the German camp at Nisibin. The narrative centre of the memoir is the story of a group of about twenty boys from the BAC who were taken prisoner at Kut. Sarbadhikari’s evocation of the sense of mounting anxiety and desperation is superb as he describes the group getting separated during the march and scattered across different camps in Mesopotamia, Turkey or Greater Syria. On his way to Ras al-‘Ain, Sarbadhikari was stunned to see scribbled on a wall of the POW camp in Mosul, in familiar handwriting, the name of his friend ‘Saachin Bose’, who had been reported ‘missing’; he also learnt that two of his friends, Amulya Chatterji and Sushil Laha, had died during the march; in Ras al-‘Ain, he was reunited with the sixteen-year-old Bhola. As Sarbadikhari got transferred to the Aleppo General Hospital, a feverish Bhola, who was being looked after by Sarbadhikari, clung to him, and sobbed hysterically ‘Dādābhāi [Elder brother], I will never survive if you leave me’ (143). If men formed intense bonds on the Western Front, Sarbadhikari shows a similar intimacy flowering among members of the BAC among the barren sands and open skies of Mesopotamia.Life in Kut was precarious, but in Ras al-‘Ain and Aleppo, the BAC boys actually started to die, including Priyo Roy, Mathew Jacob, Sailen Bose and their beloved commanding officer Amarendra Champati; Sarbadhikari also mentions the death of Kalyan Mukherji. Like the British and French nurses working on the Western front, Sarbadhikari – surrounded by the dead and dying – had trouble comprehending at night whether ‘I was alive or dead’ (148).Footnote 85 The lines between sanity and insanity, reality and nightmare began to blur: Probodh went clinically mad; Priyo seemed to see his grandmother near the hospital door just before his death in Ras al-‘Ain; Jagdish, delirious from typhoid-fever, dreamt that his leg was being burnt as kindling, a grotesque impingement on the dream-world of the practice of burning the leg-bones of horses for fire (167). Sarbadhikari dreamt that he was in the firing-line and shooting at a Turk, but the bullet ricocheted off and struck his friend Dhiren Bose in Calcutta as Owen’s ‘Strange Meeting’ gets realised in the unconscious of a Bengali non-combatant.

On 20 November 1916, Sisir was sent on a mail train to the Aleppo General Hospital or Markaz Khastakhana with fifty seriously injured patients. In contrast to the daily degradation and gratuitous cruelty of Ras al-‘Ain, the Aleppo Khastakhana, overseen by the Germans, is depicted as a more civilised space:

Aleppo is not like the cities we have seen so far, such as Baghdad and Mosul. The houses are nice to look at; the roads are not bad. We hear it looks like towns in Europe. The people on the streets look cultured; their clothes are nice; European costume predominates. There are people of many communities – Turks, Syrian Christians, Rums (i.e. Greeks) and Jews.

I was at Aleppo’s Markaz Khastakhana (hospital). We were, on the whole, friendly with the Turkish soldiers …

There were one or two Indians here, and a Romanian named Alda Sava. The Armenian doctor Shagir Effendi is a great man, he cares very much for his patients. There were two khadamas in the kaus: one was an Armenian woman called Maroom, the other a Syrian Christian man called Musha. The two of them looked after us very well. Their responsibilities were to make the bed, sweep the wards etc. …

There was another man at the Markaz khastakhana with whom we were quite friendly. He was an Armenian and his name was George. His home was in Diyar Bakr, his children had all been killed – he was the only one to escape with his life to Aleppo. George was given the task of cleaning the toilets. He cooked, slept – all at one spot. On cold days we used to go to him and we would chat while warming our hands over his angithi (coal-fire brazier). We had only a single stove in our ward and we received very little fire for kindling. (144–159)

If Kut was the realm of daily hunger and Ras al-‘Ain a place of trauma, the hospital in Aleppo in contrast was, to borrow the title of Fawaz’s masterly study, ‘the land of aching hearts’: at once a microcosm of the general displacement in the Middle East caused by the war and a place of temporary refuge for the displaced, the wounded and the derelict.

The core of the memoir in this final part is the web of encounters and relationships that developed through the way Sarbadhikari’s multiple, often contradictory, identities – as POW, as a British colonial subject, as fellow Asian, as educated and middle-class, as both friend and enemy – intersected with the multi-racial and multi-ethnic fabric of an empire in the process of modernisation, with its own hierarchies, alliances and tensions.Footnote 86 The patients in the hospital were largely Turkish as well as a few Indian, British and Russian POWs and some German and Austrian soldiers; the staff comprised Armenian doctors and muhajirs, Turkish and Arab orderlies, Kurds, Syrian Christians, Jews, Rumis. The racialising discourse that we find in English POW memoirs around the ‘barbaric Turk’ or ‘cruel Oriental’ is absent in Abhi Le Baghdad, though the author does not shy away from mentioning the regular dose of brutalities: he distinguishes between the Turkish guards, who beat him up, and the wounded Turkish soldiers, who are described as ‘pathetic’; he mentions how the hospital barber spat on his face when he went for a shave and yet, when he was ill, the Turkish orderly physically lifted him and carried him to the toilet. Hierarchies were further reversed when one day he gave the Turkish orderly ten piastres and the latter broke down in tears. It is this tessellated attention to the mixed yarn of human interaction, rather than any reductive racial discourse, which makes Abhi Le Baghdad such an exceptional piece of literature. We meet, for example, a wounded thirty-year-old Turkish soldier who, having lost his wife, would take his five-year-old daughter to battle with him, and would leave her with an acquaintance when he had to go to the front line; when Sisir would ask him about her future if he got killed, he would reply ‘Allah Biliyor’ (‘Allah knows’) (155). We meet too an elderly Turkish soldier who had come to the ward to collect cigarette-butts, only to discover that the man on the next bed was his own son with whom he had lost contact for three years!

In the hospital, Sarbadhikari was assigned to the ward of wounded Turkish soldiers; conversations started:

None of the Turkish soldiers were literate, but most of them had great fellow-feeling. They used to say, ‘You are not at war with us now, so we are all kardes [brothers].’ ‘Kardes’ was an oft-used word …

We spoke of our lands, our joys and sorrows … One thing that they always used to say was, ‘This war that we are fighting – what is our stake in this? Why are we slashing each others’ throats? You stay in Hindustan, we in Turkey, we do not know each other, share no enmity, and yet we became enemies overnight because one or two people deemed it so.’ Is this on the mind of every soldier of every nation?

Another thing that was notable about them was their hatred for the Germans. All of them used to despise the Germans – they used to say that Germany was responsible for getting them into this war. The particular cause of dissatisfaction was that the Germans would receive the best of all of Turkey’s produce. Eggs, for example, would be sent first to the German hospitals, and after their requirements were met, what remained (if anything did) would go to the Turks. It was the same with everything else. We used to think that the situation was the same in our country, but our consolation was that we were actually under British domination, but Germany and Turkey were allies!Footnote 87

What brings captive and captor together as ‘kardes’ here is the shared yoke of European subjugation and a sense of being caught up in a war that is not theirs. In contrast to the conscious ‘politics of anti-Westernism’ that Ceymil Aydin has uncovered among Asian intellectuals during the war years or even the ‘anti-colonial cosmopolitanism’ that Kris Manjapra detects among the South Asian elites, this is an international brotherhood of the dispossessed and the displaced premised on the vulnerability of being.Footnote 88 What gives Sarbadhikari’s memoir its singularity is its poignant undertow of raw experience: he captures with eerie precision the fabric of a transnational community formed not because of any conscious political ideology but out of human vulnerability at a time of conflict.

Such Indo-Turkish ‘brotherhood’ was in sharp contrast to Sarbadhikari’s cordial but somewhat distant relationship with his British fellow staff and superiors. His colleague Prafulla Chandra Sen recalled the friendship between members of the BAC and the English orderlies: they used to exchange English novels and teach each other English and Bengali songs.Footnote 89 Similarly, in Aleppo, Sarbadhikari records pockets of intimacy between the Indian captives and their colonisers-turned-fellow captives, as when he cooked a very spicy curry for Corporal Shaw, setting his haemorrhoids aflame. Yet the institutional hierarchies remained intact:

The discrimination that is always practised between the whites and the coloured is highly insulting. The white soldier gets paid twice as much as the Indian sepoy. The uniform of the two is different – that of the whites is better … In fact, whatever little provision could be made is made for the Tommy. Even the ration is different – the Tommies take tea with sugar, we are given only molasses.Footnote 90

He similarly records that, in the steamer voyage to Baghdad after the surrender at Kut, the British troops were provided with sleeping places in the lower deck while 600 sepoys were crammed into the exposed upper deck. Accounts of such everyday casual racism and colonial hierarchies are inadvertently corroborated by Major Sandes in In Kut and Captivity (1919): ‘our first business was naturally to get separate accommodation for the Indian officers’: ‘we explained also that Indian officers … were always of inferior ranks to British officers’.Footnote 91

If Abhi Le Baghdad plunges us into the minutiae of everyday life in the hospital, it is also acutely aware of the larger currents outside: it is one of the few South Asian works that bears witness to the Armenian genocide. Sarbadhikari notes that, ‘From what we hear these terrible mass killings were not perpetrated by the Turkish soldiers; they were done by Chechens and Kurds.’ (176–177). Sarbadhikari uses the word ‘hatyākāṇḍa’ (literally ‘killing-event’). At Ras al-‘Ain, one of the epicentres of the genocide, he provides an eye-witness account from his friend Sachin: ‘A group of Armenians were made to stand up, with their hands tied, and their throats were slit one by one’ (177). On the way from Ras al-‘Ain to Aleppo, Sarbadhikari met two boys of around ten who told him in broken Arabic that their parents had been killed by the Turks; as he went past a well, he saw a cloud of flies: ‘It is not at all advisable to drink from these wells; there are Armenian corpses rotting in most of them.’ (129–30). As he went past empty villages, he remembered Oliver Goldsmith’s famous 1770 poem ‘The Deserted Village’, where Goldsmith speaks about rural depopulation in wake of the Irish Famine: ‘Along thy glades, a solitary guest/Amidst the bowers, the tyrant’s hand is seen.’ (129). Yet, only a few hundred kilometres away from Ras al-‘Ain, the hospital in Aleppo, presumably under German protection, was a relatively safe zone: the chief doctor was Armenian and there was a significant Armenian presence. The most meaningful encounters in the text are those between Sarbadhikari and his Armenian fellow workers: Sarbadhikari used to idolise the chief doctor, while the Armenian muhajir looked after him like a ‘mother’ and asked about ‘the smallest details of my home and family’ (171). Similarly, Sarbadhikari records how a Punjabi sweeper rescued an Armenian boy, named him Babulal, and brought him up; it is possibly the same child whom Major E. A. Walker referred to when he mentioned ‘a small Armenian boy about ten or so’ being brought up in the Indian sepoy camp at Ras al-‘Ain.Footnote 92 At one point, Sarbadhikari observes that ‘Their lives have become ours’.

Could the above milieu at the Aleppo Khastakhana (hospital) be called ‘cosmopolitanism from below’? In Writing Culture: The Poetics and Politics of Ethnography (1986), the anthropologist Paul Rabinow observes that the term should be extended to transnational experiences that are particular rather than universal, to experiences that are not privileged, even coerced. He defines the term as ‘an ethos of macro-interdependencies, with an acute consciousness (often forced upon people) of the inescapabilities and particularities of places, characters, historical trajectories, and fates’.Footnote 93 In Sarbadhikari’s account of the hospital, Indians, Turks, Armenians, Syrian Christians, British and Russians co-habit and share life-stories, heat and food; George the Armenian receives temporary refuge and Armenian doctors tend to Turkish patients. However, these men and women come together not because of their commitment to some ethical or socio-political ideal in times of war but through the ‘unbearable vulnerability’Footnote 94 produced by historical and geopolitical entanglements. The most moving relationship in the text is the one between Sarbadhikari and the fifteen-year-old Armenian orderly Elias; as the situation worsens, Elias prepares to flee one night and Sarbadhikari gives him his most precious possession – the only warm coat he has (178). Thinking beyond yourself and giving your only warm coat to an orphan from a foreign country may be the first powerful gesture, more than any ratiocinative or intellectual exercise, towards a true cosmopolitan ethic, described as ‘feeling and thinking beyond the nation’.Footnote 95

Abhi Le Baghdad is the fullest and the most detailed among the small but immensely powerful body of testimonies on Mesopotamia by the group of Bengali non-combatants. Together, they lift the veil from over this ‘bastard war’.Footnote 96 An ode to non-combatant experiences, these memoirs show that the ‘Indian voices’ of the war can by no means be reduced to combat experience alone. Educated, nuanced and cosmopolitan, these non-combatants point to the remarkable lateral spaces, opened up by the war and empire and yet operating beyond the usual imperial axis. Indeed, these accounts help us to reconceptualise our definition of colonial war experience from one of battlefield ‘combat’ to that of conflict that includes experiences in hospitals and POW camps: what they bear witness to is not the trauma of the trenches, but a different form of experience, one that accommodates hunger and torture and forced marches as well as the kindness of strangers. What they emphasise is not the heat of battle but the precarious everydayness of war. This chapter is in many ways just a first glance, as it were, into an extraordinary range of human experiences and encounters in a part of the world which today, a hundred years on, is witnessing the same scenes of hunger and desperation. In 1919, the Arab-American poet Mikha’il Na’ima wrote poignantly of the Middle East after the war:

A hundred years later, the same images return. Let us hope for small mercies, that Elias meets another Sarbadhikari and finds shelter.