Refine search

Actions for selected content:

60621 results in Classical studies (general)

Noel A. Bonavia-Hunt: Horace the Minstrel. Pp. xviii + 268. Kineton: The Roundabout Press, 1969. Cloth, 42s.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 20 / Issue 3 / December 1970

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, pp. 401-402

- Print publication:

- December 1970

-

- Article

- Export citation

Notes on Cicero, In Pisonem

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Quarterly / Volume 20 / Issue 2 / December 1970

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 February 2009, pp. 309-321

- Print publication:

- December 1970

-

- Article

- Export citation

The Study of Archaic Poetry - J. A. Davison: From Archilochus to Pindar. Papers on Greek Literature of the Archaic Period. Pp. xxvii + 347. London: Macmillan, 1968. Cloth, 90s.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 20 / Issue 3 / December 1970

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, pp. 291-294

- Print publication:

- December 1970

-

- Article

- Export citation

CAQ volume 20 issue 2 Front matter

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Quarterly / Volume 20 / Issue 2 / December 1970

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 February 2009, pp. f1-f4

- Print publication:

- December 1970

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Export citation

Hadrian's Farewell to Life: Some Arguments for Authenticity

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Quarterly / Volume 20 / Issue 2 / December 1970

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 February 2009, pp. 372-374

- Print publication:

- December 1970

-

- Article

- Export citation

Albi, Ne Doleas - Walter Wimmel: Der frühe Tibull. (Studia et Testimonia Antiqua, vi.) Pp. 284. Munich: Wilhelm Fink, 1968. Paper, DM. 28.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 20 / Issue 3 / December 1970

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, pp. 337-340

- Print publication:

- December 1970

-

- Article

- Export citation

Corinna

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Quarterly / Volume 20 / Issue 2 / December 1970

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 February 2009, pp. 277-287

- Print publication:

- December 1970

-

- Article

- Export citation

The Supplices of Aeschylus - A. F. Garvie: Aeschylus' Supplices: Play and Trilogy. Pp. vii + 279. Cambridge: University Press, 1969. Cloth, 70s.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 20 / Issue 3 / December 1970

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, pp. 296-299

- Print publication:

- December 1970

-

- Article

- Export citation

Melica

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Quarterly / Volume 20 / Issue 2 / December 1970

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 February 2009, pp. 205-215

- Print publication:

- December 1970

-

- Article

- Export citation

Wissenschaftliche Zeitschrift der Universität Rostock. Sprachwissenschaftliche Reihe, Heft 4/5 (1966): Römische Satire. Pp. 178. Rostock: Universität. Paper.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 20 / Issue 3 / December 1970

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, p. 415

- Print publication:

- December 1970

-

- Article

- Export citation

Life and Death Questions - Uvo Hoelscher: Anfängliches Fragen: Studien zur frühen griechischen Philosophie. Pp. 221. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1968. Cloth, DM. 24.80.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 20 / Issue 3 / December 1970

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, pp. 353-355

- Print publication:

- December 1970

-

- Article

- Export citation

California Studies in Classical Antiquity. Volume I. Pp. 242; 11 plates. Berkeley: University of California Press (London: Cambridge University Press), 1969. Cloth, 81s.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 20 / Issue 3 / December 1970

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, p. 416

- Print publication:

- December 1970

-

- Article

- Export citation

Menander, Samia 13

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 20 / Issue 3 / December 1970

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, pp. 289-290

- Print publication:

- December 1970

-

- Article

- Export citation

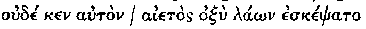

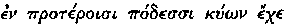

ΛAΩ: Two Testimonia in Later Greek Poetry

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Quarterly / Volume 20 / Issue 2 / December 1970

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 February 2009, pp. 306-308

- Print publication:

- December 1970

-

- Article

- Export citation

Aristotle's Oeconomicus - B. A. van Groningen, André Wartelle: Aristote, Économique. Texte établi, traduit et commenté. (Collection Budé.) Pp. xxx + 110 (text double). Paris: Les Belles Lettres, 1968. Paper, 18 fr.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 20 / Issue 3 / December 1970

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, pp. 315-319

- Print publication:

- December 1970

-

- Article

- Export citation

Sophoclean Drama - T. B. L. Webster: An Introduction to Sophocles. 2nd edition. Pp. x + 220. London: Methuen, 1969. Cloth, 32s.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 20 / Issue 3 / December 1970

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, pp. 299-300

- Print publication:

- December 1970

-

- Article

- Export citation

Vade Sed Incvltvs - Jacques André: Ovide, Tristes. (Collection Budé.) Pp. lii + 179 (text double); three folding maps. Paris: Les Belles Lettres, 1968. Paper, 30 fr.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 20 / Issue 3 / December 1970

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, pp. 340-342

- Print publication:

- December 1970

-

- Article

- Export citation

Theodore Cressy Skeat: The Reigns of the Ptolemies. (Münchener Beiträge zur Papyrusforschung, 39.) 2nd edn. Pp. vii + 43. Munich: Beck, 1969. Paper, DM. 8.50.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 20 / Issue 3 / December 1970

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, p. 412

- Print publication:

- December 1970

-

- Article

- Export citation

Three Notes on Aristophanes

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 20 / Issue 3 / December 1970

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, pp. 269-273

- Print publication:

- December 1970

-

- Article

- Export citation

Louis Bakelants: La vie et les æuvres de Gislain Bulteel d'ϒpres, 1555–1611. Contribution à l'histoire de l'humanisme dans les Pays-Bas. Ouvrage édité par Guy Cambier. (Collection Latomus, xcvii.) Pp. 490. Brussels: Latomus, 1968. Paper, 800 B.fr.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 20 / Issue 3 / December 1970

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, pp. 408-409

- Print publication:

- December 1970

-

- Article

- Export citation

The context shows that the intention of the lines was to bring out the surpassing beauty of a certain girl and its value to the chorus as a whole. When the Pleiades rise up the sky, they are followed by a star that far outshines them all: Sirius. In Alcman's image, then, the Pleiades should correspond to the chorus and Sirius to the girl. The point of opdpiai

The context shows that the intention of the lines was to bring out the surpassing beauty of a certain girl and its value to the chorus as a whole. When the Pleiades rise up the sky, they are followed by a star that far outshines them all: Sirius. In Alcman's image, then, the Pleiades should correspond to the chorus and Sirius to the girl. The point of opdpiai is that the comparison is not chosen at random, but suggested by something to be seen during the current ceremonies: the Pleiades rise up the sky

is that the comparison is not chosen at random, but suggested by something to be seen during the current ceremonies: the Pleiades rise up the sky  , where the infant Hermes is hiding in a dark cave, and (

, where the infant Hermes is hiding in a dark cave, and (

, of a hound seizing a fawn on the brooch of Odysseus. Of the several meanings suggested by the ancient lexicographers for λάω,

, of a hound seizing a fawn on the brooch of Odysseus. Of the several meanings suggested by the ancient lexicographers for λάω,  , of a hawk), and originally intended to describe the cry of a bird of prey. The unfamiliarity of the form led to its being associated later on with the

, of a hawk), and originally intended to describe the cry of a bird of prey. The unfamiliarity of the form led to its being associated later on with the