Refine search

Actions for selected content:

60621 results in Classical studies (general)

Seeing Weasels: The Superstitious Background of the Empusa Scene in the Frogs

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Quarterly / Volume 18 / Issue 2 / December 1968

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 February 2009, pp. 200-206

- Print publication:

- December 1968

-

- Article

- Export citation

R. A. Higgins: Greek Terracottas. (Methuen's Handbooks of Archaeology.) Pp. liv+169; 30 text figures, 64 plates, 4 colour plates. London: Methuen, 1967. Cloth, £7. 7s. net.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 18 / Issue 3 / December 1968

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, p. 359

- Print publication:

- December 1968

-

- Article

- Export citation

Ancient Rope—Grattius 24–7

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Quarterly / Volume 18 / Issue 2 / December 1968

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 February 2009, pp. 380-381

- Print publication:

- December 1968

-

- Article

- Export citation

Seneca on Cato's Politics: Epistle 14. 12–131

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Quarterly / Volume 18 / Issue 2 / December 1968

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 February 2009, pp. 373-375

- Print publication:

- December 1968

-

- Article

- Export citation

Propertiana

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Quarterly / Volume 18 / Issue 2 / December 1968

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 February 2009, pp. 315-319

- Print publication:

- December 1968

-

- Article

- Export citation

The Ten Thousand as a Community - G. B. Nussbaum: The Ten Thousand: a Study in Social Organization and Action in Xenophon's Anabasis. Pp. x+193. Leiden: Brill, 1967. Paper, fl.32.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 18 / Issue 3 / December 1968

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, pp. 326-327

- Print publication:

- December 1968

-

- Article

- Export citation

The End of the Western Empire - M. A. Wes: Das Ende des Kaisertums im Westen des Römischen Reiches. (Archaeologische Studie van het Nederlands Historisch Institut te Rome, ii.) Pp. 210. The Hague: Ministerie van Cultuur, 1967. Paper, fl.12.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 18 / Issue 3 / December 1968

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, pp. 336-338

- Print publication:

- December 1968

-

- Article

- Export citation

A Link between Two Manuscripts of Aristotle's De Partibus Animalium?

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Quarterly / Volume 18 / Issue 2 / December 1968

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 February 2009, pp. 279-281

- Print publication:

- December 1968

-

- Article

- Export citation

Antike Plastik. Lieferung iv: pp. 117, 24 figs., 64 pls. Lieferung v; pp. 43, 9 figs., 56 pls. Berlin: Gebr. Mann, 1965, 1966. Portfolios, DM. 105, 75.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 18 / Issue 3 / December 1968

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, pp. 358-359

- Print publication:

- December 1968

-

- Article

- Export citation

Studii Clasice, ix (1967). Pp. 398. Bucarest: Société Roumaine des Études Classiques, 1968. Cloth, lei 40.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 18 / Issue 3 / December 1968

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, p. 363

- Print publication:

- December 1968

-

- Article

- Export citation

Joan M. Fagerlie: Late Roman and Byzantine Solidi found in Sweden and Denmark. (Numismatic Notes and Monographs, 157.) Pp. xxv+213; 33 plates. New York: American Numismatic Society, 1967. Paper, $6.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 18 / Issue 3 / December 1968

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, pp. 361-362

- Print publication:

- December 1968

-

- Article

- Export citation

Socrates - Jean Humbert: Socrate et les petits Socratiques. Pp. 293. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1967. Paper, 24 fr.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 18 / Issue 3 / December 1968

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, pp. 290-292

- Print publication:

- December 1968

-

- Article

- Export citation

R. A. Crossland: Immigrants from the North. (Cambridge Ancient History, Revised Edition, Vol. i, ch. xxvii.) Pp. 61. Cambridge: University Press, 1967. Paper, 6s. net. - R. D. Barnett: Phrygia and the Peoples of Anatolia in the Iron Age. (Cambridge Ancient History, Revised Edition, Vol. ii, ch. xxx.) Pp. 32. Cambridge: University Press, 1967. Paper, 3s. 6d. net.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 18 / Issue 3 / December 1968

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, p. 356

- Print publication:

- December 1968

-

- Article

- Export citation

The Sabine Legend - J. Poucet: Recherches sur la légende sabine des origines de Rome. (Université de Louvain, Recueil de Travaux d'Histoire et de Philologie, 4e sér., fasc. 37.) Pp. xxxii+476. Louvain: Náuwelaerts, 1967. Paper, 550B.fr.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 18 / Issue 3 / December 1968

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, pp. 327-329

- Print publication:

- December 1968

-

- Article

- Export citation

Harvard Studies in Classical Philology. Volume 72. Pp. viii+405. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press (London: Oxford University Press), 1968. Cloth, 95s. net.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 18 / Issue 3 / December 1968

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, p. 364

- Print publication:

- December 1968

-

- Article

- Export citation

Minucius Felix Again - Carl Becker: Der Octavius des Minucius Felix. (Sitz. d. Bay. Akad., Phil.-Hist. Kl., 1967. 2.) Pp. III. Munich: Beck, 1967. Paper.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 18 / Issue 3 / December 1968

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, pp. 316-317

- Print publication:

- December 1968

-

- Article

- Export citation

The New Lexicon of Terence - Patrick McGlynn: Lexicon Terentianum. Vol. ii: P–V. Pp. x+315. London and Glasgow: Blackie, 1967. Cloth, £10. 10s. net.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 18 / Issue 3 / December 1968

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, pp. 302-303

- Print publication:

- December 1968

-

- Article

- Export citation

W. F. Jackson Knight: Vergil: Epic and Anthropology. Pp. 320; 2 plates, 15 figs. London: Allen & Unwin, 1967. Cloth, 55s. net.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 18 / Issue 3 / December 1968

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, p. 354

- Print publication:

- December 1968

-

- Article

- Export citation

Notes on Claudian's Invectives

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Quarterly / Volume 18 / Issue 2 / December 1968

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 February 2009, pp. 387-411

- Print publication:

- December 1968

-

- Article

- Export citation

The Roman Moral and Political Tradition - Donald Earl: The Moral and Political Tradition of Rome. Pp. 167. London: Thames & Hudson, 1967. Cloth, 30s. net.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 18 / Issue 3 / December 1968

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, pp. 332-334

- Print publication:

- December 1968

-

- Article

- Export citation

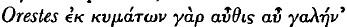

and gave the impression to the mirthful audience of having said

and gave the impression to the mirthful audience of having said

I am surprised, however, that the commentators on this line (and on Ar.

I am surprised, however, that the commentators on this line (and on Ar.