Refine search

Actions for selected content:

13581 results in History of science and technology

Myth 13 - That Huxley Defeated Wilberforce, and Ridiculed His Obscurantism, in the 1860 Oxford Debate

-

-

- Book:

- Darwin Mythology

- Published online:

- 30 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 06 June 2024, pp 148-158

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Myth 24 - That Darwin’s Theory Brought an Instant and Immediate Revolution in the Life Sciences

-

-

- Book:

- Darwin Mythology

- Published online:

- 30 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 06 June 2024, pp 273-285

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Myth 18 - That Darwin’s Theory Would Have Become More Widely Accepted Immediately Had He Read Mendel’s 1866 Paper

-

-

- Book:

- Darwin Mythology

- Published online:

- 30 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 06 June 2024, pp 204-215

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Introduction: Myths and Darwin

-

-

- Book:

- Darwin Mythology

- Published online:

- 30 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 06 June 2024, pp 1-13

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contents

-

- Book:

- Darwin Mythology

- Published online:

- 30 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 06 June 2024, pp vii-ix

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Transliterations

-

- Book:

- The Architecture of the Science of Living Beings

- Published online:

- 30 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 06 June 2024, pp xii-xii

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Myth 10 - That Darwin Delayed the Publication of His Theory for Twenty Years, Being Afraid of the Reactions It Would Cause

-

-

- Book:

- Darwin Mythology

- Published online:

- 30 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 06 June 2024, pp 115-126

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contributors

-

- Book:

- Darwin Mythology

- Published online:

- 30 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 06 June 2024, pp xii-xix

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Myth 12 - That Huxley Was Darwin’s Bulldog and Accepted All Aspects of His Theory

-

-

- Book:

- Darwin Mythology

- Published online:

- 30 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 06 June 2024, pp 137-147

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Myth 9 - That Darwin’s Theory Was Essentially Complete Once He Came Up with the Idea of Natural Selection

-

-

- Book:

- Darwin Mythology

- Published online:

- 30 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 06 June 2024, pp 103-114

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Myth 21 - That Sexual Selection Was Darwin’s Afterthought to Natural Selection

-

-

- Book:

- Darwin Mythology

- Published online:

- 30 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 06 June 2024, pp 239-249

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Myth 5 - That Darwin Converted to Evolutionary Theory During His Historic Galápagos Islands Visit

-

-

- Book:

- Darwin Mythology

- Published online:

- 30 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 06 June 2024, pp 56-67

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Copyright page

-

- Book:

- The Architecture of the Science of Living Beings

- Published online:

- 30 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 06 June 2024, pp iv-iv

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Myth 14 - That Darwin’s Critics Such as Owen Were Prejudiced and Had No Scientific Arguments

-

-

- Book:

- Darwin Mythology

- Published online:

- 30 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 06 June 2024, pp 159-170

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

BJH volume 57 issue 2 Cover and Back matter

-

- Journal:

- The British Journal for the History of Science / Volume 57 / Issue 2 / June 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 06 December 2024, pp. b1-b2

- Print publication:

- June 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Export citation

Concluding Conversation: De-centring Science Diplomacy – CORRIGENDUM

-

- Journal:

- The British Journal for the History of Science / Volume 57 / Issue 2 / June 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 04 June 2024, p. 287

- Print publication:

- June 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Performing national independence through medical diplomacy: tuberculosis control and socialist internationalism in Cold War Vietnam

-

- Journal:

- The British Journal for the History of Science / Volume 57 / Issue 2 / June 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 21 October 2024, pp. 205-220

- Print publication:

- June 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

The politics of medical expertise and substance control: WHO consultants for addiction rehabilitation and pharmacy education in Thailand and India during the Cold War

-

- Journal:

- The British Journal for the History of Science / Volume 57 / Issue 2 / June 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 28 October 2024, pp. 221-238

- Print publication:

- June 2024

-

- Article

- Export citation

BJH volume 57 issue 2 Cover and Front matter

-

- Journal:

- The British Journal for the History of Science / Volume 57 / Issue 2 / June 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 06 December 2024, pp. f1-f2

- Print publication:

- June 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Export citation

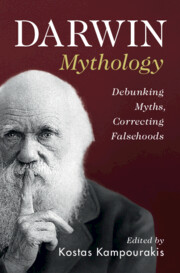

Darwin Mythology

- Debunking Myths, Correcting Falsehoods

-

- Published online:

- 30 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 06 June 2024