Refine search

Actions for selected content:

9084 results in Discrete Mathematics, Information Theory and Coding

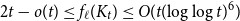

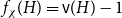

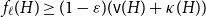

On the choosability of

$H$-minor-free graphs

$H$-minor-free graphs

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 33 / Issue 2 / March 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 03 November 2023, pp. 129-142

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

19 - Structure Constants

-

- Book:

- Equivariant Cohomology in Algebraic Geometry

- Published online:

- 07 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 26 October 2023, pp 350-369

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

15 - Homogeneous Varieties

-

- Book:

- Equivariant Cohomology in Algebraic Geometry

- Published online:

- 07 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 26 October 2023, pp 265-289

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

14 - Symplectic Schubert Polynomials

-

- Book:

- Equivariant Cohomology in Algebraic Geometry

- Published online:

- 07 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 26 October 2023, pp 240-264

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Appendix A - Algebraic Topology

-

- Book:

- Equivariant Cohomology in Algebraic Geometry

- Published online:

- 07 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 26 October 2023, pp 370-387

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

2 - Defining Equivariant Cohomology

-

- Book:

- Equivariant Cohomology in Algebraic Geometry

- Published online:

- 07 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 26 October 2023, pp 9-25

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Preface

-

- Book:

- Equivariant Cohomology in Algebraic Geometry

- Published online:

- 07 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 26 October 2023, pp xi-xvi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

11 - Degeneracy Loci

-

- Book:

- Equivariant Cohomology in Algebraic Geometry

- Published online:

- 07 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 26 October 2023, pp 182-207

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

6 - Conics

-

- Book:

- Equivariant Cohomology in Algebraic Geometry

- Published online:

- 07 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 26 October 2023, pp 79-92

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

9 - Schubert Calculus on Grassmannians

-

- Book:

- Equivariant Cohomology in Algebraic Geometry

- Published online:

- 07 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 26 October 2023, pp 126-151

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

16 - The Algebra of Divided Difference Operators

-

- Book:

- Equivariant Cohomology in Algebraic Geometry

- Published online:

- 07 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 26 October 2023, pp 290-310

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

17 - Equivariant Homology

-

- Book:

- Equivariant Cohomology in Algebraic Geometry

- Published online:

- 07 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 26 October 2023, pp 311-325

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

8 - Toric Varieties

-

- Book:

- Equivariant Cohomology in Algebraic Geometry

- Published online:

- 07 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 26 October 2023, pp 113-125

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

12 - Infinite-Dimensional Flag Varieties

-

- Book:

- Equivariant Cohomology in Algebraic Geometry

- Published online:

- 07 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 26 October 2023, pp 208-225

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Appendix C - Pfaffians and Q-polynomials

-

- Book:

- Equivariant Cohomology in Algebraic Geometry

- Published online:

- 07 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 26 October 2023, pp 392-405

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Appendix E - Characteristic Classes and Equivariant Cohomology

-

- Book:

- Equivariant Cohomology in Algebraic Geometry

- Published online:

- 07 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 26 October 2023, pp 415-419

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

7 - Localization II

-

- Book:

- Equivariant Cohomology in Algebraic Geometry

- Published online:

- 07 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 26 October 2023, pp 93-112

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

1 - Preview

-

- Book:

- Equivariant Cohomology in Algebraic Geometry

- Published online:

- 07 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 26 October 2023, pp 1-8

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

13 - Symplectic Flag Varieties

-

- Book:

- Equivariant Cohomology in Algebraic Geometry

- Published online:

- 07 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 26 October 2023, pp 226-239

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Subject Index

-

- Book:

- Equivariant Cohomology in Algebraic Geometry

- Published online:

- 07 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 26 October 2023, pp 435-446

-

- Chapter

- Export citation