Refine search

Actions for selected content:

9084 results in Discrete Mathematics, Information Theory and Coding

6 - Laurent series, amoebas, and convex geometry

- from Part II - Mathematical Background

-

- Book:

- Analytic Combinatorics in Several Variables

- Published online:

- 08 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 15 February 2024, pp 134-166

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

2 - Generating functions

- from Part I - Combinatorial Enumeration

-

- Book:

- Analytic Combinatorics in Several Variables

- Published online:

- 08 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 15 February 2024, pp 17-59

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Dedication

-

- Book:

- Analytic Combinatorics in Several Variables

- Published online:

- 08 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 15 February 2024, pp v-vi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

8 - Effective computations and ACSV

- from Part III - Multivariate Enumeration

-

- Book:

- Analytic Combinatorics in Several Variables

- Published online:

- 08 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 15 February 2024, pp 221-244

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

10 - Multiple point asymptotics

- from Part III - Multivariate Enumeration

-

- Book:

- Analytic Combinatorics in Several Variables

- Published online:

- 08 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 15 February 2024, pp 291-338

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Analytic Combinatorics in Several Variables

-

- Published online:

- 08 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 15 February 2024

Algebraic Combinatorics and the Monster Group

-

- Published online:

- 05 January 2024

- Print publication:

- 17 August 2023

Percolation on irregular high-dimensional product graphs

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 33 / Issue 3 / May 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 20 December 2023, pp. 377-403

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Product structure of graph classes with bounded treewidth

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 33 / Issue 3 / May 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 07 December 2023, pp. 351-376

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

On minimum spanning trees for random Euclidean bipartite graphs

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 33 / Issue 3 / May 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 30 November 2023, pp. 319-350

-

- Article

- Export citation

Threshold graphs maximise homomorphism densities

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 33 / Issue 3 / May 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 29 November 2023, pp. 300-318

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Spread-out limit of the critical points for lattice trees and lattice animals in dimensions

$\boldsymbol{d}\boldsymbol\gt \textbf{8}$

$\boldsymbol{d}\boldsymbol\gt \textbf{8}$

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 33 / Issue 2 / March 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 20 November 2023, pp. 238-269

-

- Article

- Export citation

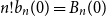

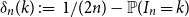

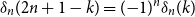

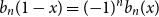

The Bernoulli clock: probabilistic and combinatorial interpretations of the Bernoulli polynomials by circular convolution

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 33 / Issue 2 / March 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 16 November 2023, pp. 210-237

-

- Article

- Export citation

Large cliques or cocliques in hypergraphs with forbidden order-size pairs

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 33 / Issue 3 / May 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 16 November 2023, pp. 286-299

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Spanning trees in graphs without large bipartite holes

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 33 / Issue 3 / May 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 14 November 2023, pp. 270-285

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- HTML

- Export citation

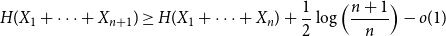

Approximate discrete entropy monotonicity for log-concave sums

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 33 / Issue 2 / March 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 13 November 2023, pp. 196-209

-

- Article

- Export citation

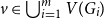

A special case of Vu’s conjecture: colouring nearly disjoint graphs of bounded maximum degree

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 33 / Issue 2 / March 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 10 November 2023, pp. 179-195

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

On oriented cycles in randomly perturbed digraphs

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 33 / Issue 2 / March 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 08 November 2023, pp. 157-178

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Mastermind with a linear number of queries

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 33 / Issue 2 / March 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 08 November 2023, pp. 143-156

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation