Refine search

Actions for selected content:

63650 results in Music

Notes

-

- Book:

- Pistols in St Paul’s

- Published by:

- Manchester University Press

- Published online:

- 31 January 2026, pp 245-276

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Plates

-

- Book:

- Pistols in St Paul’s

- Published by:

- Manchester University Press

- Published online:

- 31 January 2026, pp 297-312

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

6 - That little old echo: opportunity and transience

-

- Book:

- Pistols in St Paul’s

- Published by:

- Manchester University Press

- Published online:

- 31 January 2026, pp 174-193

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Figures

-

- Book:

- Pistols in St Paul’s

- Published by:

- Manchester University Press

- Published online:

- 31 January 2026, pp 240-244

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Acknowledgements

-

- Book:

- Pistols in St Paul’s

- Published by:

- Manchester University Press

- Published online:

- 31 January 2026, pp 234-236

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Select bibliography

-

- Book:

- Pistols in St Paul’s

- Published by:

- Manchester University Press

- Published online:

- 31 January 2026, pp 277-286

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Plates

-

- Book:

- Pistols in St Paul’s

- Published by:

- Manchester University Press

- Published online:

- 31 January 2026, pp 238-239

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

7 - Prelude to reconstruction: listening and adapting

-

- Book:

- Pistols in St Paul’s

- Published by:

- Manchester University Press

- Published online:

- 31 January 2026, pp 194-221

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Prologue: pistols in St Paul’s Cathedral

-

- Book:

- Pistols in St Paul’s

- Published by:

- Manchester University Press

- Published online:

- 31 January 2026, pp 11-25

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

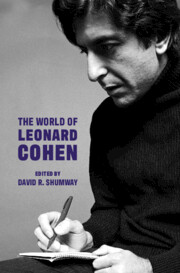

The World of Leonard Cohen

-

- Published online:

- 29 January 2026

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026

Wild colonial boys

- A Belfast punk story

-

- Published by:

- Manchester University Press

- Published online:

- 29 January 2026

A spherical microphone prototype for multichannel recording: Technological design, artistic applications and compositional implications

-

- Journal:

- Organised Sound , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 29 January 2026, pp. 1-10

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

17 - ‘The Wild Colonial Boy’

-

- Book:

- Wild colonial boys

- Published by:

- Manchester University Press

- Published online:

- 29 January 2026, pp 123-129

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contents

-

- Book:

- George Frideric Handel

- Published online:

- 23 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp v-v

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Part II - Musical Contexts

-

- Book:

- The World of Leonard Cohen

- Published online:

- 29 January 2026

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 75-122

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 2 - The Poetry and Prose

- from Part I - Creative Life

-

-

- Book:

- The World of Leonard Cohen

- Published online:

- 29 January 2026

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 29-46

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Libraries and archives

-

- Book:

- George Frideric Handel

- Published online:

- 23 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 681-683

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Frontmatter

-

- Book:

- George Frideric Handel

- Published online:

- 23 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp i-iv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

31 - The return of the native

-

- Book:

- Wild colonial boys

- Published by:

- Manchester University Press

- Published online:

- 29 January 2026, pp 239-247

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Part III - Religious Contexts

-

- Book:

- The World of Leonard Cohen

- Published online:

- 29 January 2026

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 123-164

-

- Chapter

- Export citation