1 Introduction

Extremal black holes are special solutions of Einstein’s equations of general relativity which have absolute zero temperature in the celebrated thermodynamic analogy of black hole mechanics. The simplest examples of extremal black holes are given by the extremal Reissner–Nordström (ERN) metrics

$$ \begin{align} g_{\mathrm{ERN}}\doteq -\left(1-\frac{M}{r}\right)^2dt^2+\left(1-\frac{M}{r}\right)^{-2}dr^2+r^2(d\vartheta^2+\sin^2\vartheta\,d\varphi^2), \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} g_{\mathrm{ERN}}\doteq -\left(1-\frac{M}{r}\right)^2dt^2+\left(1-\frac{M}{r}\right)^{-2}dr^2+r^2(d\vartheta^2+\sin^2\vartheta\,d\varphi^2), \end{align} $$

where M is a positive parameter known as the mass. The metric (1.1) solves the Einstein–Maxwell equations,

and is spherically symmetric, asymptotically flat, and static, with time-translation Killing vector field

![]() $T\doteq \partial _t$

.

$T\doteq \partial _t$

.

The extremal Reissner–Nordström metrics (1.1) arise as an exceptional one-parameter subfamily of the full Reissner–Nordström family [Reference Reissner62, Reference Nordström59] of solutions to the Einstein–Maxwell equations,

$$ \begin{align} g_{M,e}\doteq -\left(1-\frac{2M}{r}+\frac{e^2}{r^2}\right)dt^2+\left(1-\frac{2M}{r}+\frac{e^2}{r^2}\right)^{-1}dr^2+r^2(d\vartheta^2+\sin^2\vartheta\,d\varphi^2), \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} g_{M,e}\doteq -\left(1-\frac{2M}{r}+\frac{e^2}{r^2}\right)dt^2+\left(1-\frac{2M}{r}+\frac{e^2}{r^2}\right)^{-1}dr^2+r^2(d\vartheta^2+\sin^2\vartheta\,d\varphi^2), \end{align} $$

where e is a real parameter representing the charge of the electromagnetic field. The extremal case corresponds to the parameter values

![]() $|e|=M$

. For the parameter range

$|e|=M$

. For the parameter range

![]() $|e|\le M$

, the metric

$|e|\le M$

, the metric

![]() $g_{M,e}$

describes a black hole spacetime. When

$g_{M,e}$

describes a black hole spacetime. When

![]() $|e|<M$

, the solution is called subextremal, and the

$|e|<M$

, the solution is called subextremal, and the

![]() $|e|=M$

case corresponds to the extremal Reissner–Nordström metric (1.1) above. When

$|e|=M$

case corresponds to the extremal Reissner–Nordström metric (1.1) above. When

![]() $e=0$

,

$e=0$

,

![]() $g_{M,e}$

reduces to the celebrated Schwarzschild solution [Reference Schwarzschild65] of the Einstein vacuum equations. When

$g_{M,e}$

reduces to the celebrated Schwarzschild solution [Reference Schwarzschild65] of the Einstein vacuum equations. When

![]() $|e|>M$

, the superextremal case, the metric

$|e|>M$

, the superextremal case, the metric

![]() $g_{M,e}$

no longer describes a black hole. The role of superextremality will be discussed in Section 1.3 below.

$g_{M,e}$

no longer describes a black hole. The role of superextremality will be discussed in Section 1.3 below.

For any of the Reissner–Nordström black hole spacetimes, the Killing field satisfies

where

![]() $\mathcal H^+$

denotes the event horizon, the boundary of the black hole region. The number

$\mathcal H^+$

denotes the event horizon, the boundary of the black hole region. The number

![]() $\varkappa =\varkappa (M,e)$

, called the surface gravity of

$\varkappa =\varkappa (M,e)$

, called the surface gravity of

![]() $\mathcal H^+$

, is given by

$\mathcal H^+$

, is given by

$$ \begin{align*} \varkappa(M,e)\doteq \frac{\sqrt{M^2-e^2}}{(M+\sqrt{M^2-e^2})^2} \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \varkappa(M,e)\doteq \frac{\sqrt{M^2-e^2}}{(M+\sqrt{M^2-e^2})^2} \end{align*} $$

and quantifies the celebrated horizon redshift effect: the null generators of

![]() $\mathcal H^+$

have exponentially decaying energy, with rate determined by

$\mathcal H^+$

have exponentially decaying energy, with rate determined by

![]() $\varkappa $

(see for instance [Reference Sbierski63]).

$\varkappa $

(see for instance [Reference Sbierski63]).

The event horizon of subextremal Reissner–Nordström has

![]() $\varkappa>0$

, while the event horizon of extremal Reissner–Nordström has

$\varkappa>0$

, while the event horizon of extremal Reissner–Nordström has

![]() $\varkappa =0$

, a distinction which has fundamental repercussions for the behavior of perturbations of these spacetimes. In the seminal work [Reference Dafermos and Rodnianski29], Dafermos and Rodnianski proved the nonlinear asymptotic stability of the subextremal Reissner–Nordström family as solutions of the Einstein–Maxwell equations coupled to a neutral scalar field in spherical symmetry. The horizon redshift effect is central to [Reference Dafermos and Rodnianski29] and is a cornerstone of our understanding of linear waves on subextremal Reissner–Nordström black holes without symmetry assumptions [Reference Dafermos and Rodnianski30, Reference Dafermos and Rodnianski32]. By the work of Dafermos–Holzegel–Rodnianski [Reference Dafermos, Holzegel and Rodnianski26] and Blue [Reference Blue15] (see also [Reference Pasqualotto60]) for

$\varkappa =0$

, a distinction which has fundamental repercussions for the behavior of perturbations of these spacetimes. In the seminal work [Reference Dafermos and Rodnianski29], Dafermos and Rodnianski proved the nonlinear asymptotic stability of the subextremal Reissner–Nordström family as solutions of the Einstein–Maxwell equations coupled to a neutral scalar field in spherical symmetry. The horizon redshift effect is central to [Reference Dafermos and Rodnianski29] and is a cornerstone of our understanding of linear waves on subextremal Reissner–Nordström black holes without symmetry assumptions [Reference Dafermos and Rodnianski30, Reference Dafermos and Rodnianski32]. By the work of Dafermos–Holzegel–Rodnianski [Reference Dafermos, Holzegel and Rodnianski26] and Blue [Reference Blue15] (see also [Reference Pasqualotto60]) for

![]() $e=0$

and Giorgi [Reference Giorgi38, Reference Giorgi39] for

$e=0$

and Giorgi [Reference Giorgi38, Reference Giorgi39] for

![]() $|e|<M$

, subextremal Reissner–Nordström is now known to be linearly stable in Einstein–Maxwell theory outside of symmetry.

$|e|<M$

, subextremal Reissner–Nordström is now known to be linearly stable in Einstein–Maxwell theory outside of symmetry.

The theory of linear waves on extremal black holes – and by extension, nonlinear perturbations of extremal black holes – is very different. In a remarkable series of papers [Reference Aretakis10, Reference Aretakis11, Reference Aretakis13], Aretakis showed that ingoing null derivatives of solutions to the linear wave equation on extremal Reissner–Nordström – even those arising from well-localized initial data – generically do not decay on the event horizon, and higher derivatives may even grow polynomially in time. This horizon instability for the linear wave equation, which has become known as the Aretakis instability, has also been extended to gravitational perturbations [Reference Lucietti, Murata, Reall and Tanahashi52, Reference Apetroaie8] of extremal Reissner–Nordström and to axisymmetric linear waves on extremal Kerr [Reference Aretakis12, Reference Lucietti and Reall53]. Gajic has recently shown that extremal Kerr is subject to additional stronger instabilities arising from higher azimuthal modes [Reference Gajic35] (see also the earlier heuristic analysis [Reference Casals, Gralla and Zimmerman16]), which will be discussed further in Section 1.4.2 below.

These horizon instabilities (along with the specter of superextremality which we will address in Section 1.3 below) present a substantial obstacle to understanding the moduli space of solutions to the Einstein equations near extremal Reissner–Nordström, Kerr, and Kerr–Newman black holes. In a pioneering numerical study [Reference Murata, Reall and Tanahashi58], Murata, Reall, and Tanahashi studied spherically symmetric perturbations of extremal Reissner–Nordström in the Einstein–Maxwell-neutral scalar field model and observed that the Aretakis instability for the scalar field is still activated on the dynamical background, but that the geometry is not completely disrupted in the process. These numerical results and rigorous work on nonlinear model problems by the first-named author, Aretakis, and Gajic [Reference Angelopoulos1, Reference Angelopoulos, Aretakis and Gajic3, Reference Angelopoulos, Aretakis and Gajic7], have given rise to the hope that extremal Reissner–Nordström could be stable in spite of the Aretakis instability; see [Reference Dafermos, Holzegel, Rodnianski and Taylor27, Conjecture IV.2] and the recent essay by Dafermos [Reference Dafermos25].

1.1 Stability and instability of extremal Reissner–Nordström for the spherically symmetric Einstein–Maxwell-neutral scalar field system

In this paper, we initiate the rigorous study of the (in)stability properties of extremal Reissner–Nordström black holes as solutions to the full nonlinear Einstein field equations. We work with the spherically symmetric Einstein–Maxwell-neutral scalar field model, which is the same model as in Murata–Reall–Tanahashi [Reference Murata, Reall and Tanahashi58] (and has been used in other influential works in recent years [Reference Dafermos21, Reference Dafermos22, Reference Dafermos and Rodnianski29, Reference Luk and Oh55]). This system consists of a spherically symmetric, charged spacetime

![]() $(\mathcal M^{3+1},g,F)$

together with a spherically symmetric massless scalar field

$(\mathcal M^{3+1},g,F)$

together with a spherically symmetric massless scalar field

![]() $\phi :\mathcal M\to \mathbb R$

satisfying the linear wave equation

$\phi :\mathcal M\to \mathbb R$

satisfying the linear wave equation

on the dynamical background, with total energy-momentum tensor given by

This is one of the simplest self-gravitating models in which one can entertain dynamical nonlinear perturbations of Reissner–Nordström, as a toy model for the electro-vacuum equations. See already Section 2.1 for the precise definitions and equations of the model.

We now state rough versions of our main theorems; the detailed statements and associated definitions will be presented in Section 3 below.

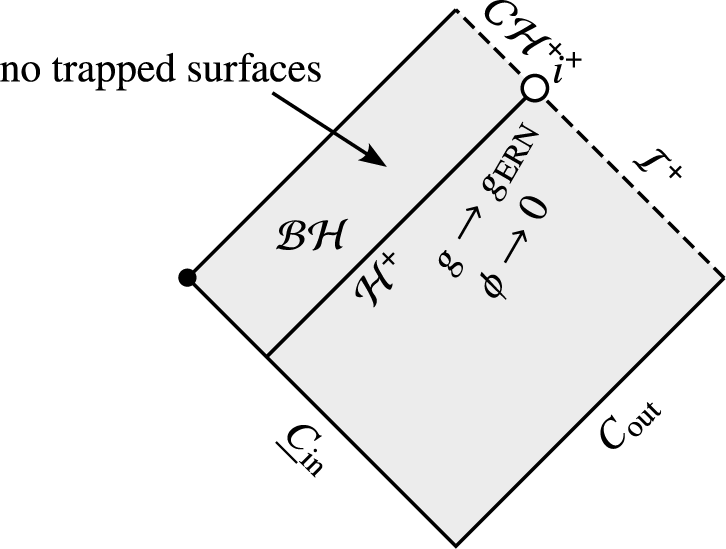

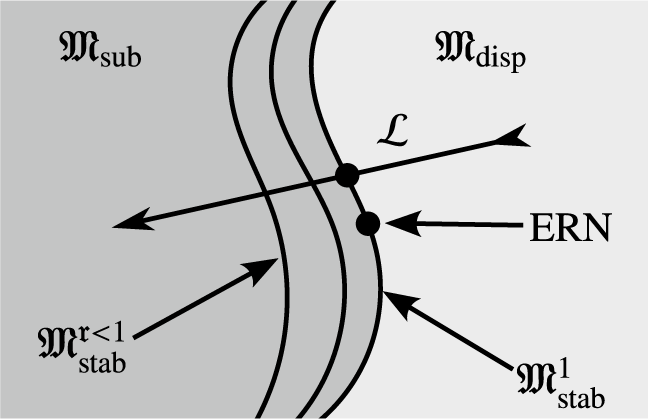

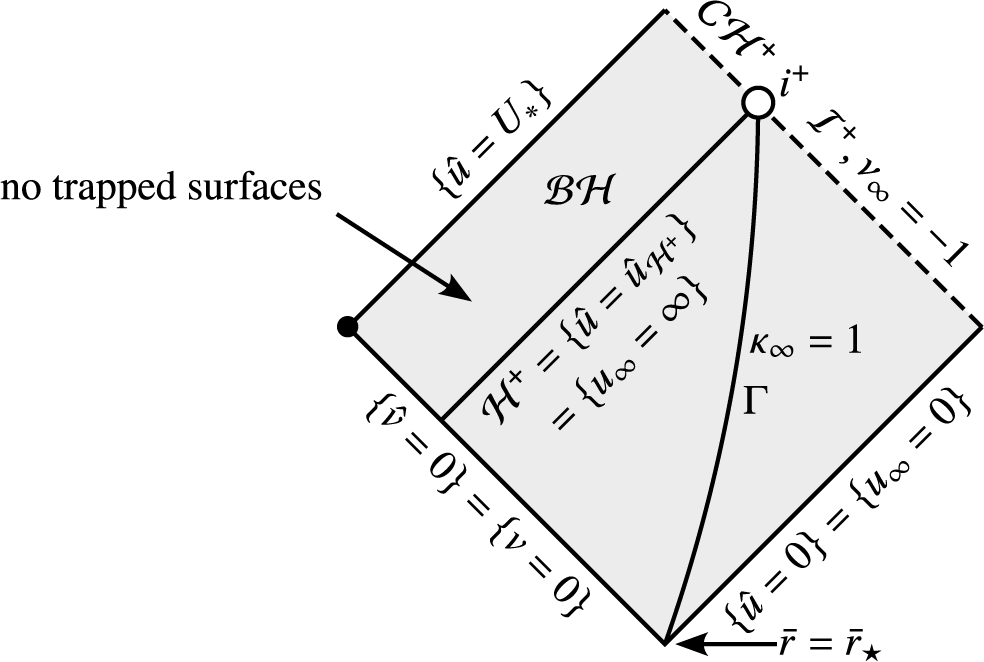

Theorem I (Codimension-one nonlinear stability of ERN, rough version).

Let

![]() ${\mathfrak{M}}$

denote the moduli space of characteristic data for the spherically symmetric Einstein–Maxwell-neutral scalar field system posed on a bifurcate null hypersurface

${\mathfrak{M}}$

denote the moduli space of characteristic data for the spherically symmetric Einstein–Maxwell-neutral scalar field system posed on a bifurcate null hypersurface

![]() $C_{\mathrm{out}}\cup \underline C{}_{\mathrm{in}}$

, as in Fig. 1 below, which lie close to extremal Reissner–Nordström in an appropriate norm. There exists a “codimension-one submanifold”

$C_{\mathrm{out}}\cup \underline C{}_{\mathrm{in}}$

, as in Fig. 1 below, which lie close to extremal Reissner–Nordström in an appropriate norm. There exists a “codimension-one submanifold”

![]() ${\mathfrak{M}}_{\mathrm{stab}}\subset {\mathfrak{M}}$

such that any data in

${\mathfrak{M}}_{\mathrm{stab}}\subset {\mathfrak{M}}$

such that any data in

![]() ${\mathfrak{M}}_{\mathrm{stab}}$

evolve into a spacetime with the following properties:

${\mathfrak{M}}_{\mathrm{stab}}$

evolve into a spacetime with the following properties:

-

(i) Future null infinity

$\mathcal I^+$

is complete and the causal past of future null infinity,

$\mathcal I^+$

is complete and the causal past of future null infinity,

$J^-(\mathcal I^+)$

, is bounded by a regular event horizon

$J^-(\mathcal I^+)$

, is bounded by a regular event horizon

$\mathcal H^+$

, which itself bounds a nonempty black hole region

$\mathcal H^+$

, which itself bounds a nonempty black hole region

$\mathcal {BH}\doteq \mathcal M\setminus J^-(\mathcal I^+)$

.

$\mathcal {BH}\doteq \mathcal M\setminus J^-(\mathcal I^+)$

. -

(ii) The metric remains close to the initial extremal Reissner–Nordström metric in the domain of outer communication and appropriately defined energy fluxes and pointwise

$C^1$

norms of the scalar field

$C^1$

norms of the scalar field

$\phi $

are bounded in terms of their initial data on

$\phi $

are bounded in terms of their initial data on

$C_{\mathrm{out}}\cup \underline C{}_{\mathrm{in}}$

.

$C_{\mathrm{out}}\cup \underline C{}_{\mathrm{in}}$

. -

(iii) The metric decays polynomially in

$C^0$

(as an appropriate notion of “time” tends to infinity) to a nearby member of the extremal Reissner–Nordström family, relative to a teleologically defined double null gauge uniformly in the entire domain of outer communication. The renormalized Hawking mass (see already Section 2.1.1) converges uniformly to the final mass of the black hole. The scalar field decays polynomially to zero pointwise and in an appropriate energy norm.

$C^0$

(as an appropriate notion of “time” tends to infinity) to a nearby member of the extremal Reissner–Nordström family, relative to a teleologically defined double null gauge uniformly in the entire domain of outer communication. The renormalized Hawking mass (see already Section 2.1.1) converges uniformly to the final mass of the black hole. The scalar field decays polynomially to zero pointwise and in an appropriate energy norm. -

(iv) The spacetime does not contain strictly trapped surfaces. Any marginally trapped surfaces lie on the event horizon

$\mathcal H^+$

.

$\mathcal H^+$

.

Figure 1 A Penrose diagram showing the maximal development of a solution considered in Theorem I. The Cauchy data ends on the left at the solid point, where it is incomplete (but not singular).

Some comments about this statement are in order:

-

1. Because the extremal Reissner–Nordström family is already codimension-one within the full Reissner–Nordström family, any stability statement for it is necessarily a positive codimension statement, with codimension one being sharp. This aspect of the problem is familiar from the proof of nonlinear stability of Schwarzschild outside of symmetry by Dafermos, Holzegel, Rodnianski, and Taylor [Reference Dafermos, Holzegel, Rodnianski and Taylor27]. For conjectures regarding the regularity of

${\mathfrak{M}}_{\mathrm{stab}}$

and what happens “on either side” of it, see already Section 1.3.

${\mathfrak{M}}_{\mathrm{stab}}$

and what happens “on either side” of it, see already Section 1.3. -

2. The theorem states that the metric decays in

$C^0$

(and some Christoffel symbols) to that of extremal Reissner–Nordström and that the scalar field decays in

$C^0$

(and some Christoffel symbols) to that of extremal Reissner–Nordström and that the scalar field decays in

$C^0$

to zero. We will show in Theorem II below that the metric does not necessarily decay to extremal Reissner–Nordström in

$C^0$

to zero. We will show in Theorem II below that the metric does not necessarily decay to extremal Reissner–Nordström in

$C^2$

(and may grow in

$C^2$

(and may grow in

$C^3$

) and that the scalar field does not necessarily decay in

$C^3$

) and that the scalar field does not necessarily decay in

$C^1$

(and may grow in

$C^1$

(and may grow in

$C^2$

).

$C^2$

). -

3. The norms and decay rates for the scalar field

$\phi $

are consistent with the norms and decay rates for spherically symmetric solutions of the linear wave equation on extremal Reissner–Nordström. We do not need to commute in order to close our bootstrap assumptions and hence do not prove sharp decay rates for

$\phi $

are consistent with the norms and decay rates for spherically symmetric solutions of the linear wave equation on extremal Reissner–Nordström. We do not need to commute in order to close our bootstrap assumptions and hence do not prove sharp decay rates for

$\phi $

everywhere. See already Sections 1.2 and 1.4.1.

$\phi $

everywhere. See already Sections 1.2 and 1.4.1. -

4. Since we show that there are no trapped surfaces behind the event horizon, we in fact prove that the maximal development of data in

${\mathfrak{M}}_{\mathrm{stab}}$

is the full double null rectangle depicted in Fig. 1. For the behavior of the scalar field and geometry in the black hole interior, see already Section 1.3.2.

${\mathfrak{M}}_{\mathrm{stab}}$

is the full double null rectangle depicted in Fig. 1. For the behavior of the scalar field and geometry in the black hole interior, see already Section 1.3.2.

Our second main theorem shows that the Aretakis instability of the event horizon, i.e., nondecay of the first transverse derivative and linear growth of the second transverse derivative, persists in the Einstein–Maxwell-scalar field model. Moreover, in this coupled model, the instability affects the geometry as well.

Before stating the theorem, we recall briefly some features of the geometry of extremal Reissner–Nordström black holes. Let Y denote the coordinate vector field

![]() $\partial _r$

in ingoing Eddington–Finkelstein coordinates

$\partial _r$

in ingoing Eddington–Finkelstein coordinates

![]() $(v,r,\vartheta ,\varphi )$

. This null vector field is translation-invariant and transverse to the event horizon. Moreover, it is canonical in the sense that for any spherically symmetric double null coordinates

$(v,r,\vartheta ,\varphi )$

. This null vector field is translation-invariant and transverse to the event horizon. Moreover, it is canonical in the sense that for any spherically symmetric double null coordinates

![]() $(u,v,\vartheta ,\varphi )$

on extremal Reissner–Nordström with u “ingoing,” Y can be written as

$(u,v,\vartheta ,\varphi )$

on extremal Reissner–Nordström with u “ingoing,” Y can be written as

![]() $(\partial _ur)^{-1}\partial _u$

. The

$(\partial _ur)^{-1}\partial _u$

. The

![]() $YY$

-component of the Ricci tensor,

$YY$

-component of the Ricci tensor,

![]() $R_{YY}$

, vanishes identically on any Reissner–Nordström solution.

$R_{YY}$

, vanishes identically on any Reissner–Nordström solution.

Theorem II (Dynamical horizon instability, rough version).

For any initial data lying in

![]() ${\mathfrak{M}}_{\mathrm{stab}}$

, the following holds on the event horizon

${\mathfrak{M}}_{\mathrm{stab}}$

, the following holds on the event horizon

![]() $\mathcal H^+$

of its maximal globally hyperbolic development:

$\mathcal H^+$

of its maximal globally hyperbolic development:

-

(i) Let

$Y\doteq (\partial _ur)^{-1}\partial _u$

denote the gauge-invariant null derivative transverse to

$Y\doteq (\partial _ur)^{-1}\partial _u$

denote the gauge-invariant null derivative transverse to

$\mathcal H^+$

, where r is the area-radius of the spacetime, and u is a retarded time coordinate, i.e., increasing towards the black hole. Then

$\mathcal H^+$

, where r is the area-radius of the spacetime, and u is a retarded time coordinate, i.e., increasing towards the black hole. Then

$R_{YY}$

and

$R_{YY}$

and

$Y(r\phi )$

are approximately constant on

$Y(r\phi )$

are approximately constant on

$\mathcal H^+$

, i.e., do not necessarily decay.

$\mathcal H^+$

, i.e., do not necessarily decay. -

(ii) There exists a relatively open subset of

${\mathfrak{M}}_{\mathrm{stab}}$

for which the “asymptotic Aretakis charge” (1.6)is nonvanishing. Here v is an advanced time coordinate on the spacetime such that

${\mathfrak{M}}_{\mathrm{stab}}$

for which the “asymptotic Aretakis charge” (1.6)is nonvanishing. Here v is an advanced time coordinate on the spacetime such that $$ \begin{align} H_0[\phi]\doteq \lim_{v\to\infty}Y(r\phi)|_{\mathcal H^+}(v) \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} H_0[\phi]\doteq \lim_{v\to\infty}Y(r\phi)|_{\mathcal H^+}(v) \end{align} $$

$v=\infty $

at future timelike infinity

$v=\infty $

at future timelike infinity

$i^+$

. It holds that (1.7)

$i^+$

. It holds that (1.7) $$ \begin{align} \lim_{v\to\infty}R_{YY}|_{\mathcal H^+}(v)= 2M^{-2}\big(H_0[\phi]\big)^2. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \lim_{v\to\infty}R_{YY}|_{\mathcal H^+}(v)= 2M^{-2}\big(H_0[\phi]\big)^2. \end{align} $$

-

(iii) If

$H_0[\phi ]\ne 0$

, then there exists a constant

$H_0[\phi ]\ne 0$

, then there exists a constant

$c>0$

such that (1.8)

$c>0$

such that (1.8) $$ \begin{align} \big|\nabla_YR_{YY}|_{\mathcal H^+}(v)\big|\ge cv,\qquad \big|Y^2(r\phi)|_{\mathcal H^+} (v)\big|\ge cv. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \big|\nabla_YR_{YY}|_{\mathcal H^+}(v)\big|\ge cv,\qquad \big|Y^2(r\phi)|_{\mathcal H^+} (v)\big|\ge cv. \end{align} $$

As was mentioned before, the problem considered here was previously investigated numerically by Murata, Reall, and Tanahashi in [Reference Murata, Reall and Tanahashi58]. Theorems I and II rigorously confirm all of their findings about the black hole exterior and event horizon for initial data in

![]() ${\mathfrak{M}}_{\mathrm{stab}}$

and make precise the nature of the “fine tuning” required to asymptote to extremality. Their findings about the black hole interior at extremality are also verified by combining Theorem I with the work of Gajic and Luk [Reference Gajic and Luk36]; see already Section 1.3.2.

${\mathfrak{M}}_{\mathrm{stab}}$

and make precise the nature of the “fine tuning” required to asymptote to extremality. Their findings about the black hole interior at extremality are also verified by combining Theorem I with the work of Gajic and Luk [Reference Gajic and Luk36]; see already Section 1.3.2.

Remark 1.1. The nondecay and growth of

![]() $R_{YY}$

and

$R_{YY}$

and

![]() $\nabla _YR_{YY}$

along

$\nabla _YR_{YY}$

along

![]() $\mathcal H^+$

found in the present paper is distinct from the nondecay and growth of

$\mathcal H^+$

found in the present paper is distinct from the nondecay and growth of

![]() $\underline \alpha $

and

$\underline \alpha $

and ![]() found by Apetroaie in [Reference Apetroaie8] for the generalized Teukolsky system on extremal Reissner–Nordström, where

found by Apetroaie in [Reference Apetroaie8] for the generalized Teukolsky system on extremal Reissner–Nordström, where

![]() $\underline \alpha {}_{AB}\doteq W(e_A,Y,e_B,Y)$

, where W is the Weyl tensor, and

$\underline \alpha {}_{AB}\doteq W(e_A,Y,e_B,Y)$

, where W is the Weyl tensor, and

![]() $\{e_A\}_{A=1,2}$

span the symmetry spheres. Indeed,

$\{e_A\}_{A=1,2}$

span the symmetry spheres. Indeed,

![]() $\underline \alpha $

vanishes identically for a spherically symmetric metric.

$\underline \alpha $

vanishes identically for a spherically symmetric metric.

In this paper, we do not pursue the interesting question of which other geometric quantities exhibit instabilities at higher orders of differentiability.

1.2 Overview of the proof

The proof of Theorem I involves a bootstrap argument with a teleologically normalized double null gauge coupled to a discrete modulation argument performed on dyadic timescales. Theorem II is proved by combining the method of characteristics for the wave equation for

![]() $\phi $

with precise estimates on the dynamical degenerate redshift factor along the event horizon

$\phi $

with precise estimates on the dynamical degenerate redshift factor along the event horizon

![]() $\mathcal H^+$

. We now describe the proofs in some detail, beginning with the relevant theory for the linear wave equation on extremal Reissner–Nordström.

$\mathcal H^+$

. We now describe the proofs in some detail, beginning with the relevant theory for the linear wave equation on extremal Reissner–Nordström.

1.2.1 Review of spherically symmetric linear waves on extremal Reissner–Nordström and the Aretakis instability

Here we briefly review the theory of spherically symmetric solutions to the linear wave equation (1.5) on extremal Reissner–Nordström. Aretakis initiated the study of this problem in [Reference Aretakis10, Reference Aretakis11] but we will make use of technical advances made by the first-named author, Aretakis, and Gajic in [Reference Angelopoulos, Aretakis and Gajic5, Reference Angelopoulos, Aretakis and Gajic4, Reference Angelopoulos, Aretakis and Gajic6]. For a brief review of the geometry of extremal Reissner–Nordström, we refer the reader to Section 2.2 of the present paper, [Reference Aretakis10, Section 2], and the appendix of [Reference Aretakis9].

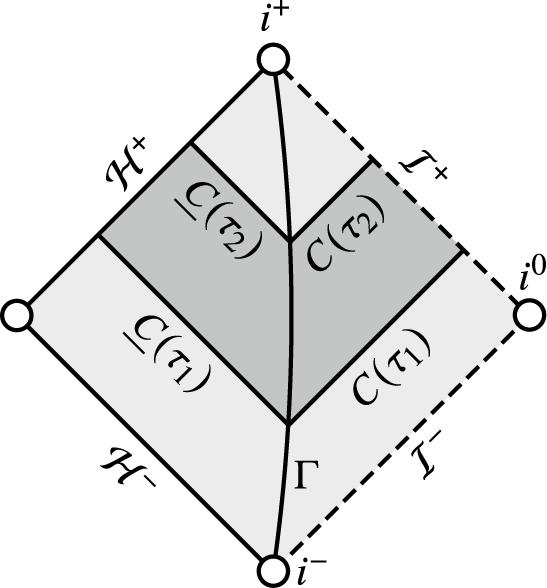

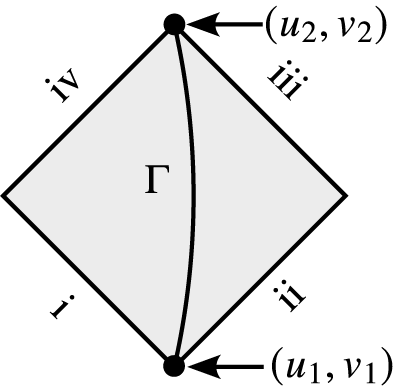

The general strategy to prove energy decay statements for waves on extremal Reissner–Nordström consists of, as in the subextremal case, deriving a hierarchy of weighted energy boundedness inequalities and time-integrated energy decay estimates. This hierarchy takes the form

$$ \begin{align} &\int_{C(\tau_2)}r^p(\partial_v\psi)^2\, dv+ \int_{\underline C(\tau_2)} (r-M)^{2-p} \frac{(\partial_u\psi)^2}{-\partial_ur}\,du \nonumber\\& \quad\lesssim \int_{C(\tau_1)}r^p(\partial_v\psi)^2\, dv+ \int_{\underline C(\tau_1)} (r-M)^{2-p} \frac{(\partial_u\psi)^2}{-\partial_ur}\,du+\mathrm{l.o.t.}, \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} &\int_{C(\tau_2)}r^p(\partial_v\psi)^2\, dv+ \int_{\underline C(\tau_2)} (r-M)^{2-p} \frac{(\partial_u\psi)^2}{-\partial_ur}\,du \nonumber\\& \quad\lesssim \int_{C(\tau_1)}r^p(\partial_v\psi)^2\, dv+ \int_{\underline C(\tau_1)} (r-M)^{2-p} \frac{(\partial_u\psi)^2}{-\partial_ur}\,du+\mathrm{l.o.t.}, \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \int_{\tau_1}^{\tau_2}\int_{C(\tau)} r^{p-1}(\partial_v\psi)^2\, dvd\tau&\lesssim \int_{C(\tau_1)}r^p(\partial_v\psi)^2\, dv + \text{l.o.t.}, \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \int_{\tau_1}^{\tau_2}\int_{C(\tau)} r^{p-1}(\partial_v\psi)^2\, dvd\tau&\lesssim \int_{C(\tau_1)}r^p(\partial_v\psi)^2\, dv + \text{l.o.t.}, \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \int_{\tau_1}^{\tau_2}\int_{\underline C(\tau)} (r-M)^{3-p} \frac{(\partial_u\psi)^2}{-\partial_ur}\,dud\tau&\lesssim\int_{\underline C(\tau_1)} (r-M)^{2-p} \frac{(\partial_u\psi)^2}{-\partial_ur}\,du + \text{l.o.t.}, \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \int_{\tau_1}^{\tau_2}\int_{\underline C(\tau)} (r-M)^{3-p} \frac{(\partial_u\psi)^2}{-\partial_ur}\,dud\tau&\lesssim\int_{\underline C(\tau_1)} (r-M)^{2-p} \frac{(\partial_u\psi)^2}{-\partial_ur}\,du + \text{l.o.t.}, \end{align} $$

where

![]() $(u,v)$

denote Eddington–Finkelstein double null coordinates on the domain of outer communication,

$(u,v)$

denote Eddington–Finkelstein double null coordinates on the domain of outer communication,

![]() $\tau $

is proper time along a timelike curve

$\tau $

is proper time along a timelike curve

![]() $\Gamma $

with constant area-radius,

$\Gamma $

with constant area-radius,

![]() $\tau _1\le \tau _2$

,

$\tau _1\le \tau _2$

,

![]() $p\in [0,3)$

in (1.9),

$p\in [0,3)$

in (1.9),

![]() $p\in [1,3)$

in (1.10) and (1.11), “l.o.t.” denotes terms lower in the p-hierarchy, the foliations

$p\in [1,3)$

in (1.10) and (1.11), “l.o.t.” denotes terms lower in the p-hierarchy, the foliations

![]() $C(\tau )$

and

$C(\tau )$

and

![]() $\underline C(\tau )$

are defined pictorially in Fig. 2, and

$\underline C(\tau )$

are defined pictorially in Fig. 2, and

![]() $\psi $

denotes the radiation field

$\psi $

denotes the radiation field

Remark 1.2. The range of our horizon and infinity hierarchies is considered for

![]() $p \in [0,3-\delta ]$

. Specifically, at the horizon, this range is sharp, and it is necessary for us to go beyond

$p \in [0,3-\delta ]$

. Specifically, at the horizon, this range is sharp, and it is necessary for us to go beyond

![]() $p \geq 2$

in order to simultaneously close the bootstrap argument for both the scalar field and the geometric quantities.

$p \geq 2$

in order to simultaneously close the bootstrap argument for both the scalar field and the geometric quantities.

Remark 1.3. The expression

![]() $(\partial _u\psi )^2(-\partial _ur)^{-1}du$

is invariant under reparametrization of the double null gauge and represents a nondegenerate one-form along

$(\partial _u\psi )^2(-\partial _ur)^{-1}du$

is invariant under reparametrization of the double null gauge and represents a nondegenerate one-form along

![]() $\underline C(\tau )$

. Indeed, written in ingoing Eddington–Finkelstein coordinates

$\underline C(\tau )$

. Indeed, written in ingoing Eddington–Finkelstein coordinates

![]() $(v,r)$

, it corresponds to

$(v,r)$

, it corresponds to

![]() $(\partial _r\psi )^2\,dr$

along

$(\partial _r\psi )^2\,dr$

along

![]() $\underline C(\tau )$

, which is manifestly nondegenerate.

$\underline C(\tau )$

, which is manifestly nondegenerate.

The inequality (1.10) is the celebrated

![]() $r^p$

-weighted estimate of Dafermos and Rodnianski [Reference Dafermos and Rodnianski31] and relies only on the asymptotic flatness of the extremal Reissner–Nordström metric. The estimate (1.11) is specific to extremal Reissner–Nordström and can be thought of as a “horizon analogue” of the

$r^p$

-weighted estimate of Dafermos and Rodnianski [Reference Dafermos and Rodnianski31] and relies only on the asymptotic flatness of the extremal Reissner–Nordström metric. The estimate (1.11) is specific to extremal Reissner–Nordström and can be thought of as a “horizon analogue” of the

![]() $r^p$

estimates at infinity: The event horizon

$r^p$

estimates at infinity: The event horizon

![]() $\mathcal H^+$

of extremal Reissner–Nordström is located at

$\mathcal H^+$

of extremal Reissner–Nordström is located at

![]() $r=M$

and hence

$r=M$

and hence

![]() $r-M$

is a degenerate weight on

$r-M$

is a degenerate weight on

![]() $\mathcal H^+$

. The estimate (1.11) states that the time integral of the

$\mathcal H^+$

. The estimate (1.11) states that the time integral of the

![]() $(p-1)$

-weighted horizon flux is bounded by the initial value of the p-weighted horizon flux. This horizon hierarchy – some special cases of which were introduced in [Reference Aretakis10] and in full generality was presented in [Reference Angelopoulos, Aretakis and Gajic6] – replaces the fundamental redshift estimate from [Reference Dafermos and Rodnianski30, Reference Dafermos and Rodnianski32] which holds for any stationary event horizon with positive surface gravity. Note that the

$(p-1)$

-weighted horizon flux is bounded by the initial value of the p-weighted horizon flux. This horizon hierarchy – some special cases of which were introduced in [Reference Aretakis10] and in full generality was presented in [Reference Angelopoulos, Aretakis and Gajic6] – replaces the fundamental redshift estimate from [Reference Dafermos and Rodnianski30, Reference Dafermos and Rodnianski32] which holds for any stationary event horizon with positive surface gravity. Note that the

![]() $p=0$

horizon flux is equivalent to the T-energy, where T is the time-translation Killing field. The duality between r and

$p=0$

horizon flux is equivalent to the T-energy, where T is the time-translation Killing field. The duality between r and

![]() $(r-M)^{-1}$

is related to the so-called Couch–Torrence conformal isometry [Reference Couch and Torrence20] that exchanges

$(r-M)^{-1}$

is related to the so-called Couch–Torrence conformal isometry [Reference Couch and Torrence20] that exchanges

![]() $\mathcal H^+$

and

$\mathcal H^+$

and

![]() $\mathcal I^+$

in extremal Reissner–Nordström.

$\mathcal I^+$

in extremal Reissner–Nordström.

Using the pigeonhole principle as in [Reference Dafermos and Rodnianski31], (1.9)–(1.11) can be used to prove the energy decay estimate

$$ \begin{align} \int_{C(\tau)} r^p(\partial_v\psi)^2\, dv+\int_{\underline C(\tau)} (r-M)^{2-p} \frac{(\partial_u\psi)^2}{-\partial_ur}\,du \le C_\star\tau^{-3+\delta+p}, \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \int_{C(\tau)} r^p(\partial_v\psi)^2\, dv+\int_{\underline C(\tau)} (r-M)^{2-p} \frac{(\partial_u\psi)^2}{-\partial_ur}\,du \le C_\star\tau^{-3+\delta+p}, \end{align} $$

for every

![]() $p\in [0,3-\delta ]$

and

$p\in [0,3-\delta ]$

and

![]() $\tau \ge \tau _0$

, where

$\tau \ge \tau _0$

, where

![]() $C_\star $

is a constant depending on

$C_\star $

is a constant depending on

![]() $\delta $

and the data at

$\delta $

and the data at

![]() $\tau =\tau _0$

. This estimate can then be used to prove pointwise decay of

$\tau =\tau _0$

. This estimate can then be used to prove pointwise decay of

![]() $\psi $

itself. By commuting the wave equation, higher order versions of (1.9)–(1.12) can be proved, but we shall not need to do so in the present paper.

$\psi $

itself. By commuting the wave equation, higher order versions of (1.9)–(1.12) can be proved, but we shall not need to do so in the present paper.

Remark 1.4. Observe that (1.12) for

![]() $p=2$

states that the nondegenerate energy of

$p=2$

states that the nondegenerate energy of

![]() $\partial _u\psi $

decays only like

$\partial _u\psi $

decays only like

![]() $\tau ^{-1+\delta }$

, compared to

$\tau ^{-1+\delta }$

, compared to

![]() $\tau ^{-3+\delta }$

or

$\tau ^{-3+\delta }$

or

![]() $\tau ^{-2+\delta }$

in the subextremal case (depending on the assumptions for the decay of the data at infinity – see, for example, [Reference Angelopoulos, Aretakis and Gajic5]). Unfortunately, this is in fact sharp for generic data (see [Reference Angelopoulos, Aretakis and Gajic2]) and persists in the nonlinear theory, see already Sections 1.4.1 and 9.3. This slow decay is responsible for many of the technical difficulties we face in the present paper and will be discussed again in Section 1.2.4 below.

$\tau ^{-2+\delta }$

in the subextremal case (depending on the assumptions for the decay of the data at infinity – see, for example, [Reference Angelopoulos, Aretakis and Gajic5]). Unfortunately, this is in fact sharp for generic data (see [Reference Angelopoulos, Aretakis and Gajic2]) and persists in the nonlinear theory, see already Sections 1.4.1 and 9.3. This slow decay is responsible for many of the technical difficulties we face in the present paper and will be discussed again in Section 1.2.4 below.

While certain energies for

![]() $\phi $

do indeed decay by (1.12), the Aretakis instability states that nondegenerate ingoing null derivatives of

$\phi $

do indeed decay by (1.12), the Aretakis instability states that nondegenerate ingoing null derivatives of

![]() $\phi $

on

$\phi $

on

![]() $\mathcal H^+$

do not decay, or can even grow polynomially. We now briefly explain this mechanism. Let

$\mathcal H^+$

do not decay, or can even grow polynomially. We now briefly explain this mechanism. Let

![]() $Y\doteq \partial _r$

in ingoing Eddington–Finkelstein coordinates

$Y\doteq \partial _r$

in ingoing Eddington–Finkelstein coordinates

![]() $(v,r)$

.Footnote 1 An elementary calculation using the wave equation (1.5) shows that

$(v,r)$

.Footnote 1 An elementary calculation using the wave equation (1.5) shows that

i.e.,

![]() $Y\psi $

is constant along

$Y\psi $

is constant along

![]() $\mathcal H^+$

. Therefore, in sharp contrast to the subextremal case,

$\mathcal H^+$

. Therefore, in sharp contrast to the subextremal case,

![]() $Y\psi $

does not decay along

$Y\psi $

does not decay along

![]() $\mathcal H^+$

. This constant is written as

$\mathcal H^+$

. This constant is written as

![]() $H_0[\phi ]$

and is called the (zeroth) Aretakis charge of

$H_0[\phi ]$

and is called the (zeroth) Aretakis charge of

![]() $\phi $

.

$\phi $

.

By commuting the wave equation with Y, we can likewise derive an evolution equation for

![]() $Y^2\psi $

along

$Y^2\psi $

along

![]() $\mathcal H^+$

. If

$\mathcal H^+$

. If

![]() $H_0[\phi ]\ne 0$

, we have that

$H_0[\phi ]\ne 0$

, we have that

so upon integrating in v we conclude that

![]() $|Y^2\psi |\gtrsim |H_0[\phi ]|v$

on

$|Y^2\psi |\gtrsim |H_0[\phi ]|v$

on

![]() $\mathcal H^+$

for v large. In fact, we have

$\mathcal H^+$

for v large. In fact, we have

![]() $|Y^k\psi |\gtrsim |H_0[\phi ]|v^{k-1}$

on

$|Y^k\psi |\gtrsim |H_0[\phi ]|v^{k-1}$

on

![]() $\mathcal H^+$

for any

$\mathcal H^+$

for any

![]() $k\ge 1$

and v large.

$k\ge 1$

and v large.

1.2.2 Prescription of seed data and the modulation parameter

$\alpha $

$\alpha $

Keeping in mind the ideas of Section 1.2.1, we now turn to the outline of the proofs of Theorems I and II.

We recall the notion of renormalized Hawking mass, which is the appropriate analogue of the usual Hawking mass

![]() $m\doteq \frac {r}{2}(1-g(\nabla r,\nabla r))$

for solutions of the spherically symmetric Einstein–Maxwell-neutral scalar field model:

$m\doteq \frac {r}{2}(1-g(\nabla r,\nabla r))$

for solutions of the spherically symmetric Einstein–Maxwell-neutral scalar field model:

where e is the constant charge of the solution. In Reissner–Nordström with parameters M and e,

![]() $\varpi =M$

.

$\varpi =M$

.

We refer back to the Penrose diagram of the setup of our main results, Fig. 1. Bifurcate characteristic seed data for the spherically symmetric Einstein–Maxwell-neutral scalar field model on

![]() $C_{\mathrm{out}}\cup \underline C{}_{\mathrm{in}}$

consists of the restriction of

$C_{\mathrm{out}}\cup \underline C{}_{\mathrm{in}}$

consists of the restriction of

![]() $\phi $

to

$\phi $

to

![]() $C_{\mathrm{out}}\cup \underline C{}_{\mathrm{in}}$

, denoted by

$C_{\mathrm{out}}\cup \underline C{}_{\mathrm{in}}$

, denoted by

![]() $\mathring \phi $

, the area-radius

$\mathring \phi $

, the area-radius

![]() $\Lambda $

of

$\Lambda $

of

![]() $C_{\mathrm{out}}\cap \underline C{}_{\mathrm{in}}$

, the renormalized Hawking mass

$C_{\mathrm{out}}\cap \underline C{}_{\mathrm{in}}$

, the renormalized Hawking mass

![]() $\varpi _0$

of

$\varpi _0$

of

![]() $C_{\mathrm{out}}\cap \underline C{}_{\mathrm{in}}$

, and the electric charge e of the Maxwell field F, which is defined in (2.4) below. Since the scalar field is neutral, e is in fact globally conserved and is thus fixed once and for all by the initial data. The collection of such quadruples

$C_{\mathrm{out}}\cap \underline C{}_{\mathrm{in}}$

, and the electric charge e of the Maxwell field F, which is defined in (2.4) below. Since the scalar field is neutral, e is in fact globally conserved and is thus fixed once and for all by the initial data. The collection of such quadruples

![]() $(\mathring \phi ,\Lambda ,\varpi _0,e)$

is what we call the moduli space of initial data

$(\mathring \phi ,\Lambda ,\varpi _0,e)$

is what we call the moduli space of initial data

![]() ${\mathfrak{M}}$

.

${\mathfrak{M}}$

.

Fix extremal parameters

![]() $M_0=|e_0|$

and an area-radius

$M_0=|e_0|$

and an area-radius

![]() $100M_0$

(which lies far outside the horizon located at

$100M_0$

(which lies far outside the horizon located at

![]() $r=M_0$

). We consider perturbations of the bifurcate cone in the extremal Reissner–Nordström solution with parameters

$r=M_0$

). We consider perturbations of the bifurcate cone in the extremal Reissner–Nordström solution with parameters

![]() $(M_0,e_0)$

with bifurcation sphere at

$(M_0,e_0)$

with bifurcation sphere at

![]() $r=100M_0$

. We consider the seed data norm

$r=100M_0$

. We consider the seed data norm

and define a master smallness parameter

![]() $\varepsilon \ge \mathfrak D$

. Here

$\varepsilon \ge \mathfrak D$

. Here

![]() $(\hat u,\hat v)$

are “initial data normalized” coordinates such that

$(\hat u,\hat v)$

are “initial data normalized” coordinates such that

![]() $\partial _{\hat u}r=-1$

on

$\partial _{\hat u}r=-1$

on

![]() $\underline C{}_{\mathrm{in}}$

and

$\underline C{}_{\mathrm{in}}$

and

![]() $\partial _{\hat v}r=1$

on

$\partial _{\hat v}r=1$

on

![]() $C_{\mathrm{out}}$

. In particular,

$C_{\mathrm{out}}$

. In particular,

![]() $\hat u$

will be regular across the event horizon.

$\hat u$

will be regular across the event horizon.

As in [Reference Dafermos, Holzegel, Rodnianski and Taylor27], we in fact consider a family of initial data which are indexed by a real parameter

![]() $\alpha $

such that

$\alpha $

such that

![]() $\varpi _0=M_0+\alpha $

. Therefore, for

$\varpi _0=M_0+\alpha $

. Therefore, for

![]() $(\mathring \phi ,\Lambda ,e)$

fixed, the “codimension-one” aspect of Theorem I means that we find (at least one)

$(\mathring \phi ,\Lambda ,e)$

fixed, the “codimension-one” aspect of Theorem I means that we find (at least one)

![]() $\alpha =\alpha _\star $

such that the solution generated by the seed data

$\alpha =\alpha _\star $

such that the solution generated by the seed data

![]() $(\mathring \phi ,\Lambda ,M_0+\alpha _\star ,e)$

converges to extremal Reissner–Nordström with parameters

$(\mathring \phi ,\Lambda ,M_0+\alpha _\star ,e)$

converges to extremal Reissner–Nordström with parameters

![]() $M=|e|$

and e. The critical parameter

$M=|e|$

and e. The critical parameter

![]() $\alpha _\star $

is determined in evolution and cannot be read off from the initial data. See already Section 1.2.6.

$\alpha _\star $

is determined in evolution and cannot be read off from the initial data. See already Section 1.2.6.

Remark 1.5. Varying

![]() $\alpha $

in our construction corresponds exactly to varying the parameter

$\alpha $

in our construction corresponds exactly to varying the parameter

![]() $M_i$

in the numerical setup of [Reference Murata, Reall and Tanahashi58], so we are indeed finding the “same” codimension-one family of asymptotically extremal Reissner–Nordström solutions. However, our modulation scheme is completely different from theirs.

$M_i$

in the numerical setup of [Reference Murata, Reall and Tanahashi58], so we are indeed finding the “same” codimension-one family of asymptotically extremal Reissner–Nordström solutions. However, our modulation scheme is completely different from theirs.

The setup for the initial data is given in Section 3.1.

1.2.3 Setup of the bootstrap argument and the teleological gauge

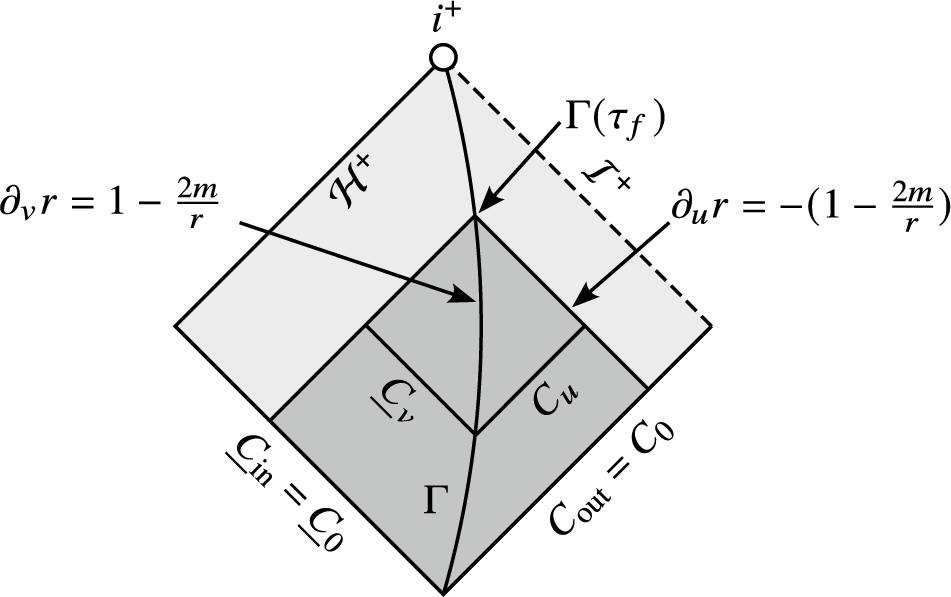

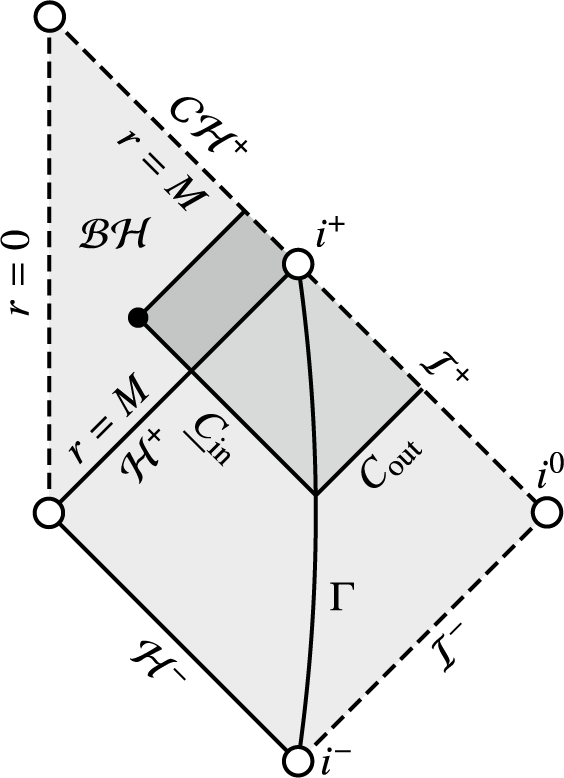

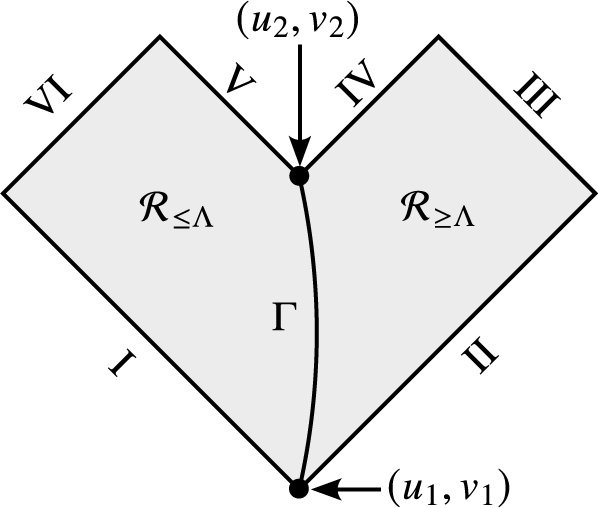

Our general setup for the bootstrap argument (depicted in Fig. 3 below) is inspired by [Reference Dafermos, Holzegel, Rodnianski and Taylor27] and the work of Luk–Oh [Reference Luk and Oh56] on stability of subextremal Reissner–Nordström in spherical symmetry.

Figure 3 A Penrose diagram of one of the bootstrap domains

![]() $\mathcal{D}{}_{\tau{}_{f}}{\doteq} J^-(\Gamma(\tau_f))$

used in the proof of Theorem I. Here

$\mathcal{D}{}_{\tau{}_{f}}{\doteq} J^-(\Gamma(\tau_f))$

used in the proof of Theorem I. Here

![]() $\Gamma {\doteq}\{r=\Lambda \}$

is the timelike curve which anchors the bootstrap domains and

$\Gamma {\doteq}\{r=\Lambda \}$

is the timelike curve which anchors the bootstrap domains and

![]() $(u,v)$

are double null coordinates teleologically normalized as depicted.

$(u,v)$

are double null coordinates teleologically normalized as depicted.

In Fig. 3, the timelike curve

![]() $\Gamma $

has constant area-radius

$\Gamma $

has constant area-radius

![]() $r=\Lambda $

(from the seed data) and is parametrized by proper time

$r=\Lambda $

(from the seed data) and is parametrized by proper time

![]() $\tau \ge 1$

. The parameter

$\tau \ge 1$

. The parameter

![]() $\tau _f$

determines the bootstrap domain

$\tau _f$

determines the bootstrap domain

![]() $\mathcal D_{\tau _f}$

and is sent to infinity in the course of the proof. The double null coordinates

$\mathcal D_{\tau _f}$

and is sent to infinity in the course of the proof. The double null coordinates

![]() $(u,v)$

are teleologically normalized according to the conditions

$(u,v)$

are teleologically normalized according to the conditions

![]() $\partial _ur=-(1-\frac {2m}{r})$

on the ingoing future boundary of

$\partial _ur=-(1-\frac {2m}{r})$

on the ingoing future boundary of

![]() $\mathcal D_{\tau _f}$

, where m is the Hawking mass of the spacetime, and

$\mathcal D_{\tau _f}$

, where m is the Hawking mass of the spacetime, and

![]() $\partial _vr=1-\frac {2m}{r}$

on

$\partial _vr=1-\frac {2m}{r}$

on

![]() $\Gamma $

. This latter gauge condition for the v coordinate is nonstandard and marks a crucial difference with the subextremal case in [Reference Luk and Oh56, Reference Dafermos, Holzegel, Rodnianski and Taylor27]. We extend

$\Gamma $

. This latter gauge condition for the v coordinate is nonstandard and marks a crucial difference with the subextremal case in [Reference Luk and Oh56, Reference Dafermos, Holzegel, Rodnianski and Taylor27]. We extend

![]() $\tau $

to a function on

$\tau $

to a function on

![]() $\mathcal D_{\tau _f}$

by setting it equal to proper time along

$\mathcal D_{\tau _f}$

by setting it equal to proper time along

![]() $\Gamma $

and then declaring it to be constant along ingoing cones to the left of

$\Gamma $

and then declaring it to be constant along ingoing cones to the left of

![]() $\Gamma $

and constant along outgoing cones to the right of

$\Gamma $

and constant along outgoing cones to the right of

![]() $\Gamma $

.

$\Gamma $

.

Since the charge e is conserved, we know a priori that we should aim to converge to extremal Reissner–Nordström with parameters

![]() $M\doteq |e|$

and e. We anchor a comparison extremal Reissner–Nordström solution with area-radius function

$M\doteq |e|$

and e. We anchor a comparison extremal Reissner–Nordström solution with area-radius function

![]() $\bar r$

and parameters

$\bar r$

and parameters

![]() $(M,e)$

in Eddington–Finkelstein double null gauge to the bootstrap domain

$(M,e)$

in Eddington–Finkelstein double null gauge to the bootstrap domain

![]() $\mathcal D_{\tau _f}$

by setting

$\mathcal D_{\tau _f}$

by setting

![]() $\bar r(\Gamma (\tau _f))=\Lambda $

. Relative to this background solution, we define energy norms motivated by the uncoupled case (recall Section 1.2.1),

$\bar r(\Gamma (\tau _f))=\Lambda $

. Relative to this background solution, we define energy norms motivated by the uncoupled case (recall Section 1.2.1),

$$ \begin{align*} \mathcal E_p(\tau) &\doteq \int_{C_{\Gamma^u(\tau)}\cap\mathcal D_{\tau_f}}r^p(\partial_v\psi)^2\, dv+\cdots ,\\ \underline{\mathcal E}{}_p(\tau) & \doteq\int_{\underline C{}_{\Gamma^u(\tau)}\cap\mathcal D_{\tau_f}} (\bar r-M)^{2-p}\frac{(\partial_u\psi)^2}{-\partial_u\bar r} \,du+\cdots, \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \mathcal E_p(\tau) &\doteq \int_{C_{\Gamma^u(\tau)}\cap\mathcal D_{\tau_f}}r^p(\partial_v\psi)^2\, dv+\cdots ,\\ \underline{\mathcal E}{}_p(\tau) & \doteq\int_{\underline C{}_{\Gamma^u(\tau)}\cap\mathcal D_{\tau_f}} (\bar r-M)^{2-p}\frac{(\partial_u\psi)^2}{-\partial_u\bar r} \,du+\cdots, \end{align*} $$

where we have only written the most important terms for now.

Remark 1.6. In the definition of

![]() $\mathcal E_p$

, we use the “dynamical” r and not the background

$\mathcal E_p$

, we use the “dynamical” r and not the background

![]() $\bar r$

. This is because the

$\bar r$

. This is because the

![]() $r^p$

estimates in spherical symmetry do not generate nonlinear errors and r works just as well as

$r^p$

estimates in spherical symmetry do not generate nonlinear errors and r works just as well as

![]() $\bar r$

in the far region. The use of

$\bar r$

in the far region. The use of

![]() $\bar r-M$

in

$\bar r-M$

in

![]() $\underline {\mathcal E}{}_p$

is crucial, however.

$\underline {\mathcal E}{}_p$

is crucial, however.

For the modulation parameter

![]() $\alpha $

lying in an appropriate range (to be explained in Section 1.2.6 below), we make the bootstrap assumptions

$\alpha $

lying in an appropriate range (to be explained in Section 1.2.6 below), we make the bootstrap assumptions

$$ \begin{align} \left|\frac{\partial_ur}{\partial_u\bar r}-1\right|\lesssim \varepsilon^{3/2}\tau^{-1+\delta},\quad |r-\bar r|\lesssim \varepsilon^{3/2}\tau^{-2+\delta},\quad |\varpi-M|\lesssim \varepsilon^{3/2}\tau^{-3+\delta} \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \left|\frac{\partial_ur}{\partial_u\bar r}-1\right|\lesssim \varepsilon^{3/2}\tau^{-1+\delta},\quad |r-\bar r|\lesssim \varepsilon^{3/2}\tau^{-2+\delta},\quad |\varpi-M|\lesssim \varepsilon^{3/2}\tau^{-3+\delta} \end{align} $$

on

![]() $\mathcal D_{\tau _f}$

for the geometry and

$\mathcal D_{\tau _f}$

for the geometry and

for

![]() $\tau \in [1,\tau _f]$

for the scalar field; compare with (1.12).Footnote 2 The main analytic content of Theorem I consists of recovering the bootstrap assumptions (1.16) and (1.17).

$\tau \in [1,\tau _f]$

for the scalar field; compare with (1.12).Footnote 2 The main analytic content of Theorem I consists of recovering the bootstrap assumptions (1.16) and (1.17).

The setup for the bootstrap argument is given in Section 3.2, the anchoring procedure is given in Section 3.3, and the bootstrap assumptions are precisely stated in Section 4.1.

1.2.4 Estimates for the geometry: the role of the degenerate redshift

We utilize the well-known quantities

$$ \begin{align*} \kappa\doteq \frac{\partial_vr}{1-\frac{2m}{r}},\quad \gamma\doteq \frac{\partial_ur}{1-\frac{2m}{r}}, \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \kappa\doteq \frac{\partial_vr}{1-\frac{2m}{r}},\quad \gamma\doteq \frac{\partial_ur}{1-\frac{2m}{r}}, \end{align*} $$

which satisfy good evolution equations in u and v, respectively. The background extremal Reissner–Nordström solution

![]() $\bar r $

has

$\bar r $

has

![]() $\bar \kappa =-\bar \gamma =1$

globally. Therefore, the anchoring and gauge conditions ensure that

$\bar \kappa =-\bar \gamma =1$

globally. Therefore, the anchoring and gauge conditions ensure that

![]() $r(\Gamma (\tau _f))=\bar r(\Gamma (\tau _f))$

,

$r(\Gamma (\tau _f))=\bar r(\Gamma (\tau _f))$

,

![]() $\kappa =\bar \kappa =1$

along

$\kappa =\bar \kappa =1$

along

![]() $\Gamma \cap \mathcal D_{\tau _f}$

, and

$\Gamma \cap \mathcal D_{\tau _f}$

, and

![]() $\gamma =\bar \gamma =-1$

along the final ingoing cone in

$\gamma =\bar \gamma =-1$

along the final ingoing cone in

![]() $\mathcal D_{\tau _f}$

.

$\mathcal D_{\tau _f}$

.

The v-equation for

![]() $\gamma $

sees the flux

$\gamma $

sees the flux

![]() $\mathcal E_0$

and hence gives us that

$\mathcal E_0$

and hence gives us that

![]() $\gamma =-1 + O(\varepsilon ^2\tau ^{-3+\delta })$

, which is the best that can be expected. On the other hand, the u-equation for

$\gamma =-1 + O(\varepsilon ^2\tau ^{-3+\delta })$

, which is the best that can be expected. On the other hand, the u-equation for

![]() $\kappa $

reads

$\kappa $

reads

![]() $\partial _u\kappa = r\kappa (\partial _ur)^{-1}(\partial _u\phi )^2$

, which sees

$\partial _u\kappa = r\kappa (\partial _ur)^{-1}(\partial _u\phi )^2$

, which sees

![]() $\underline {\mathcal E}{}_2$

, and hence decays much slower.Footnote 3 On the other hand, the quantity

$\underline {\mathcal E}{}_2$

, and hence decays much slower.Footnote 3 On the other hand, the quantity

![]() $(\bar r-M)^{2-p}(\kappa -\bar \kappa )$

, for

$(\bar r-M)^{2-p}(\kappa -\bar \kappa )$

, for

![]() $p\in [0,2]$

, obeys a u-evolution equation that sees the flux

$p\in [0,2]$

, obeys a u-evolution equation that sees the flux

![]() $\underline {\mathcal E}{}_p$

when integrating to the left of

$\underline {\mathcal E}{}_p$

when integrating to the left of

![]() $\Gamma $

, and hence we show that

$\Gamma $

, and hence we show that

to the left of

![]() $\Gamma $

. This hierarchy of decay rates for

$\Gamma $

. This hierarchy of decay rates for

![]() $\kappa $

is a fundamental aspect of our geometric estimates.

$\kappa $

is a fundamental aspect of our geometric estimates.

Because of this, it is important not to waste any powers of

![]() $\bar r-M$

in the system and our scheme is essentially sharp at the horizon in this regard. Of particular importance are the quantities

$\bar r-M$

in the system and our scheme is essentially sharp at the horizon in this regard. Of particular importance are the quantities

![]() $1-\frac {2m}{r}$

and

$1-\frac {2m}{r}$

and

![]() $\partial _vr$

, which we show admit “Taylor expansions” of the form

$\partial _vr$

, which we show admit “Taylor expansions” of the form

In the background solution, the quantities

![]() $ \overline {1-\frac {2m}{r}} $

and

$ \overline {1-\frac {2m}{r}} $

and

![]() $\partial _v\bar r$

vanish quadratically on

$\partial _v\bar r$

vanish quadratically on

![]() $\mathcal H^+$

, so these are to be viewed as expansions in powers of

$\mathcal H^+$

, so these are to be viewed as expansions in powers of

![]() $\bar r-M$

with rapidly decaying error.

$\bar r-M$

with rapidly decaying error.

The coefficients of the terms which are linear in

![]() $\bar r-M$

and the strong decay of the error terms in (1.19) and (1.20) are important. For example, the function

$\bar r-M$

and the strong decay of the error terms in (1.19) and (1.20) are important. For example, the function

![]() $1-\frac {2m}{r}$

appears naturally in the u-equation for

$1-\frac {2m}{r}$

appears naturally in the u-equation for

![]() $\varpi $

, which reads

$\varpi $

, which reads

![]() $\partial _u\varpi = \tfrac 12 (1-\frac {2m}{r})r^2(\partial _ur)^{-1}(\partial _u\phi )^2$

, and proving

$\partial _u\varpi = \tfrac 12 (1-\frac {2m}{r})r^2(\partial _ur)^{-1}(\partial _u\phi )^2$

, and proving

![]() $\tau ^{-3+\delta }$

decay for this requires taking advantage of the linear term in (1.19). In the subextremal case, the redshift effect implies one can prove

$\tau ^{-3+\delta }$

decay for this requires taking advantage of the linear term in (1.19). In the subextremal case, the redshift effect implies one can prove

![]() $\tau ^{-3+\delta }$

decay for

$\tau ^{-3+\delta }$

decay for

![]() $\varpi $

while completely ignoring the

$\varpi $

while completely ignoring the

![]() $1-\frac {2m}{r}$

weight, so no expansion of the form (1.19) is required (or helpful). Moreover, we use the linear term in (1.19) to control the error term in (1.20).

$1-\frac {2m}{r}$

weight, so no expansion of the form (1.19) is required (or helpful). Moreover, we use the linear term in (1.19) to control the error term in (1.20).

The sign of the linear term in (1.20) is crucial: it is positive in the domain of outer communication, which reflects the global redshift effect on extremal Reissner–Nordström. However, unlike the subextremal case, where the redshift leads to an exponentially decaying integrating factor for the analogue of (1.20) (compare [Reference Luk and Oh56, Lemma 8.19]), on an asymptotically extremal black hole the effect degenerates on the horizon and the rapidly decaying error term becomes important, since integrating (1.20) in v now loses a power of

![]() $\tau $

. See also Remark 5.12 below.

$\tau $

. See also Remark 5.12 below.

The geometric estimates are proved in Section 5.

1.2.5 Integrated local energy decay and the

$r^p$

and

$r^p$

and

$(\bar r-M)^{2-p}$

energy hierarchies

$(\bar r-M)^{2-p}$

energy hierarchies

To recover the bootstrap assumption (1.17) for the scalar field, we follow the general strategy outlined in Section 1.2.1. We prove the estimates

for

![]() $1\le \tau _1\le \tau _2$

and

$1\le \tau _1\le \tau _2$

and

![]() $p\in [0,3-\delta ]$

, and

$p\in [0,3-\delta ]$

, and

$$ \begin{align} \int_{\tau_1}^{\tau_2}\big( \mathcal E_{p-1}(\tau)+ \underline{\mathcal E}{}_{p-1}(\tau)\big)\,d\tau \lesssim \mathcal E_p(\tau_1)+ \underline{\mathcal E}{}_p(\tau_1)+ \text{decaying nonlinear error} \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \int_{\tau_1}^{\tau_2}\big( \mathcal E_{p-1}(\tau)+ \underline{\mathcal E}{}_{p-1}(\tau)\big)\,d\tau \lesssim \mathcal E_p(\tau_1)+ \underline{\mathcal E}{}_p(\tau_1)+ \text{decaying nonlinear error} \end{align} $$

for

![]() $p\in [1,3-\delta ]$

. The choice of multiplier vector fields and lower order currents is inspired by work in the uncoupled case and [Reference Luk and Oh56]. We utilize a mix of “dynamical” (i.e., defined relative to the dynamical metric) and “background” (i.e., defined relative to the background extremal Reissner–Nordström metric

$p\in [1,3-\delta ]$

. The choice of multiplier vector fields and lower order currents is inspired by work in the uncoupled case and [Reference Luk and Oh56]. We utilize a mix of “dynamical” (i.e., defined relative to the dynamical metric) and “background” (i.e., defined relative to the background extremal Reissner–Nordström metric

![]() $\bar r$

) multipliers to minimize the number of error terms. The expansion (1.19) is used crucially to estimate nonlinear errors in the near-horizon region that are specific to the extremal case. Once (1.21) and (1.22) have been proved, decay is inferred by a standard application of the pigeonhole principle as in [Reference Dafermos and Rodnianski31].

$\bar r$

) multipliers to minimize the number of error terms. The expansion (1.19) is used crucially to estimate nonlinear errors in the near-horizon region that are specific to the extremal case. Once (1.21) and (1.22) have been proved, decay is inferred by a standard application of the pigeonhole principle as in [Reference Dafermos and Rodnianski31].

The energy hierarchies are defined in Section 6 and energy decay is proved in Section 7.

1.2.6 The codimension-one “submanifold”

${\mathfrak{M}}_{\mathrm{stab}}$

and modulation on dyadic timescales

${\mathfrak{M}}_{\mathrm{stab}}$

and modulation on dyadic timescales

While our bootstrap argument is performed continuously in time, the choice of allowed modulation parameters

![]() $\alpha $

is only decided when

$\alpha $

is only decided when

![]() $\tau _f$

is dyadic, i.e., a power of 2. This approach is motivated by the purely dyadic approach of Dafermos–Holzegel–Rodnianski–Taylor in [Reference Dafermos, Holzegel, Rodnianski and Taylor28] and turns out to be quite fortuitous compared to the continuous-in-time modulation theory employed in [Reference Dafermos, Holzegel, Rodnianski and Taylor27].

$\tau _f$

is dyadic, i.e., a power of 2. This approach is motivated by the purely dyadic approach of Dafermos–Holzegel–Rodnianski–Taylor in [Reference Dafermos, Holzegel, Rodnianski and Taylor28] and turns out to be quite fortuitous compared to the continuous-in-time modulation theory employed in [Reference Dafermos, Holzegel, Rodnianski and Taylor27].

In practice, we construct a sequence of nested compact intervals

![]() $\mathfrak A_0\supset \mathfrak A_1\supset \cdots $

such that

$\mathfrak A_0\supset \mathfrak A_1\supset \cdots $

such that

![]() $\mathfrak A_i$

consists of those

$\mathfrak A_i$

consists of those

![]() $\alpha $

’s which we consider for bootstrap time

$\alpha $

’s which we consider for bootstrap time

![]() $\tau _f\in [2^i,2^{i+1})$

. These sets are defined implicitly by the requirement that the renormalized Hawking mass

$\tau _f\in [2^i,2^{i+1})$

. These sets are defined implicitly by the requirement that the renormalized Hawking mass

![]() $\varpi $

at the point

$\varpi $

at the point

![]() $\Gamma (2^i)$

must lie within

$\Gamma (2^i)$

must lie within

![]() $\varepsilon ^{3/2}2^{(-3+\delta )i}$

of M for

$\varepsilon ^{3/2}2^{(-3+\delta )i}$

of M for

![]() $\alpha \in \mathfrak A_i$

. By a shooting argument at each dyadic time

$\alpha \in \mathfrak A_i$

. By a shooting argument at each dyadic time

![]() $2^i$

, we show that the implicitly defined set

$2^i$

, we show that the implicitly defined set

![]() $\mathfrak A_i$

is nonempty. Therefore, as

$\mathfrak A_i$

is nonempty. Therefore, as

![]() $\tau _f\to \infty $

(and, consequently,

$\tau _f\to \infty $

(and, consequently,

![]() $i\to \infty $

), we extract (at least one) critical parameter

$i\to \infty $

), we extract (at least one) critical parameter

![]() $\alpha _\star \in \bigcap _{i\ge 0}\mathfrak A_i$

for which the solution tends to extremality. The stable “submanifold”

$\alpha _\star \in \bigcap _{i\ge 0}\mathfrak A_i$

for which the solution tends to extremality. The stable “submanifold”

![]() ${\mathfrak{M}}_{\mathrm{stab}}\subset {\mathfrak{M}}$

is the collection of all seed data sets of the form

${\mathfrak{M}}_{\mathrm{stab}}\subset {\mathfrak{M}}$

is the collection of all seed data sets of the form

![]() $(\mathring \phi ,\Lambda ,M_0+\alpha _\star ,e)$

and is codimension-one in the sense that every “line” of constant

$(\mathring \phi ,\Lambda ,M_0+\alpha _\star ,e)$

and is codimension-one in the sense that every “line” of constant

![]() $\mathring \phi $

,

$\mathring \phi $

,

![]() $\Lambda $

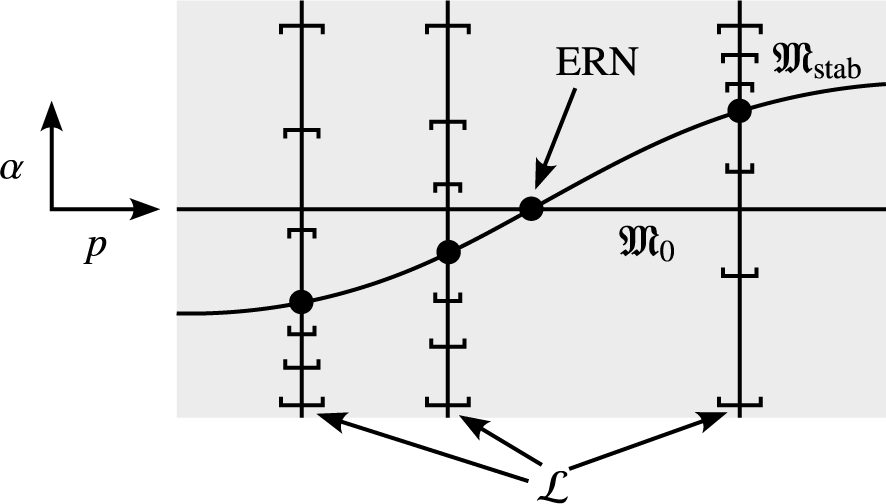

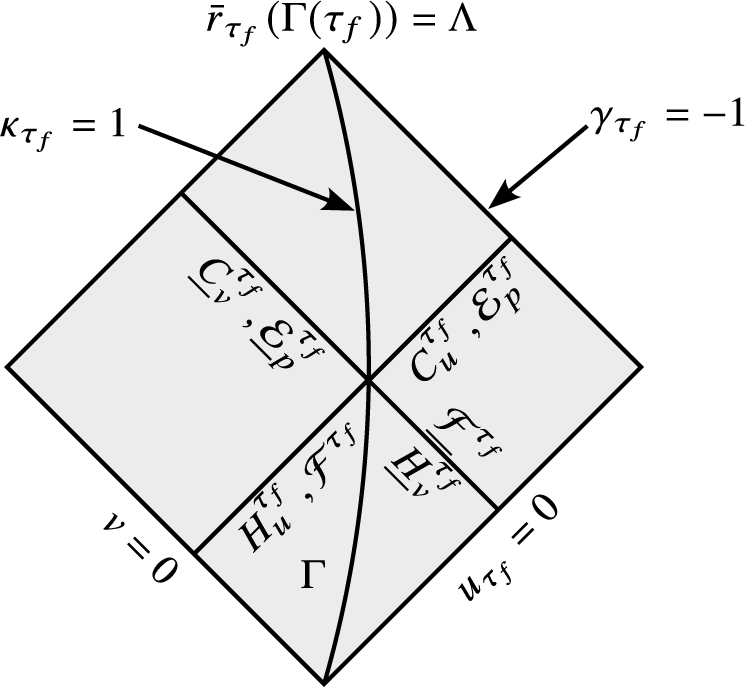

, and e intersects it at least once.Footnote 4 Refer to Fig. 4 below.

$\Lambda $

, and e intersects it at least once.Footnote 4 Refer to Fig. 4 below.

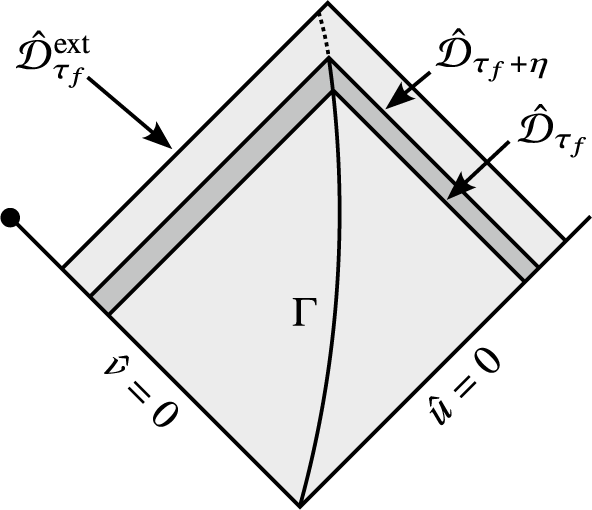

Figure 4 A schematic depiction of our modulation scheme. Let

![]() $p\mapsto \mathring \phi (p)$

be a one-parameter family of characteristic initial data for the scalar field with

$p\mapsto \mathring \phi (p)$

be a one-parameter family of characteristic initial data for the scalar field with

![]() $\mathring \phi (0)=0$

. We can then consider the plane in

$\mathring \phi (0)=0$

. We can then consider the plane in

![]() ${\mathfrak{M}}$

parametrized by

${\mathfrak{M}}$

parametrized by

![]() $(p,\alpha )$

. Each p generates a line segment

$(p,\alpha )$

. Each p generates a line segment

![]() $\mathcal L$

in

$\mathcal L$

in

![]() ${\mathfrak{M}}$

which intersects the “submanifold”

${\mathfrak{M}}$

which intersects the “submanifold”

![]() ${\mathfrak{M}}_{\mathrm{stab}}$

at least once. The horizontal line

${\mathfrak{M}}_{\mathrm{stab}}$

at least once. The horizontal line

![]() ${\mathfrak{M}}_0$

denotes the hyperplane in

${\mathfrak{M}}_0$

denotes the hyperplane in

![]() ${\mathfrak{M}}$

consisting of data sets with

${\mathfrak{M}}$

consisting of data sets with

![]() $\varpi _0=M_0$

. On the three

$\varpi _0=M_0$

. On the three

![]() $\mathcal L$

’s depicted here, we have also drawn three of the nested modulation sets

$\mathcal L$

’s depicted here, we have also drawn three of the nested modulation sets

![]() $\mathfrak A_i$

which converge to

$\mathfrak A_i$

which converge to

![]() $\mathcal L\cap {\mathfrak{M}}_{\mathrm{stab}}$

. Note that we have drawn

$\mathcal L\cap {\mathfrak{M}}_{\mathrm{stab}}$

. Note that we have drawn

![]() ${\mathfrak{M}}_{\mathrm{stab}}$

as a smooth, connected curve here, which is in line with our conjectures in Section 1.3, but we do not prove any such fine structure of it in this paper.

${\mathfrak{M}}_{\mathrm{stab}}$

as a smooth, connected curve here, which is in line with our conjectures in Section 1.3, but we do not prove any such fine structure of it in this paper.

Since we construct

![]() $\mathfrak A_i$

only after each dyadic time, we may always assume a

$\mathfrak A_i$

only after each dyadic time, we may always assume a

![]() $\tau ^{-3+\delta }$

decay rate for the difference

$\tau ^{-3+\delta }$

decay rate for the difference

![]() $\varpi -M$

, which is sharp. This should be contrasted with [Reference Dafermos, Holzegel, Rodnianski and Taylor27], where the assumption on angular momentum in the modulation set has a decay rate of

$\varpi -M$

, which is sharp. This should be contrasted with [Reference Dafermos, Holzegel, Rodnianski and Taylor27], where the assumption on angular momentum in the modulation set has a decay rate of

![]() $\tau _f^{-1}$

, but the improvement (i.e., the change in angular momentum along

$\tau _f^{-1}$

, but the improvement (i.e., the change in angular momentum along

![]() $\mathcal I^+$

) is required to decay like

$\mathcal I^+$

) is required to decay like

![]() $\tau _f^{-2}$

, which is a significant technical issue. In our work, both the assumption and the improvement have the sharp decay rate

$\tau _f^{-2}$

, which is a significant technical issue. In our work, both the assumption and the improvement have the sharp decay rate

![]() $\tau _f^{-3+\delta }$

and the gain is purely in the power of

$\tau _f^{-3+\delta }$

and the gain is purely in the power of

![]() $\varepsilon $

(

$\varepsilon $

(

![]() $\varepsilon ^{3/2}$

vs.

$\varepsilon ^{3/2}$

vs.

![]() $\varepsilon ^2$

); see already (8.1). This strong decay rate for

$\varepsilon ^2$

); see already (8.1). This strong decay rate for

![]() $\varpi -M$

is important, in particular because of the absence of redshift in the geometric estimates.

$\varpi -M$

is important, in particular because of the absence of redshift in the geometric estimates.

We have depicted our modulation scheme in Fig. 4 above. The modulation sets

![]() $\mathfrak A_i$

are defined in Section 4.1 and the modulation argument is performed in Section 8.1.2. Modulation on dyadic timescales, motivated by [Reference Dafermos, Holzegel, Rodnianski and Taylor28], has also been performed by Kádár in [Reference Kádár47, Reference Kádár46].

$\mathfrak A_i$

are defined in Section 4.1 and the modulation argument is performed in Section 8.1.2. Modulation on dyadic timescales, motivated by [Reference Dafermos, Holzegel, Rodnianski and Taylor28], has also been performed by Kádár in [Reference Kádár47, Reference Kádár46].

1.2.7 Construction of the eschatological gauge and background solution

Recall from Section 1.2.3 that the teleologically normalized coordinate u and the background extremal Reissner–Nordström solution

![]() $\bar r$

depend on the bootstrap time

$\bar r$

depend on the bootstrap time

![]() $\tau _f$

. Therefore, an important final step when taking

$\tau _f$

. Therefore, an important final step when taking

![]() $\tau _f\to \infty $

is to prove that we can define a unique “final background solution” which we converge to and an “eschatological gauge” (i.e., final teleological gauge) in which we converge to it. The regularity of the limiting gauge is actually related to the decay assumptions on initial data,Footnote 5 and the best that can be hoped for given only the finiteness of (1.15) is that the final u coordinate is a

$\tau _f\to \infty $

is to prove that we can define a unique “final background solution” which we converge to and an “eschatological gauge” (i.e., final teleological gauge) in which we converge to it. The regularity of the limiting gauge is actually related to the decay assumptions on initial data,Footnote 5 and the best that can be hoped for given only the finiteness of (1.15) is that the final u coordinate is a

![]() $C^2$

function of the initial data coordinate

$C^2$

function of the initial data coordinate

![]() $\hat u$

. These limiting arguments are carried out in Sections 8.2 and 8.3.

$\hat u$

. These limiting arguments are carried out in Sections 8.2 and 8.3.

1.2.8 Absence of trapped surfaces and rigidity of the apparent horizon

After we have constructed the dynamical extremal spacetimes, it remains to prove part (iv) of Theorem I. This argument is originally due to Kommemi (in unpublished work) and a very similar argument appears in [Reference Luk and Oh55, Appendix A]. The first aspect of the argument is a proof that any point on the outermost apparent horizon

![]() $\mathcal A'$

must lie on

$\mathcal A'$

must lie on

![]() $\mathcal H^+$

because of simple monotonicities to the right of

$\mathcal H^+$

because of simple monotonicities to the right of

![]() $\mathcal A'$

and the fact that r and

$\mathcal A'$

and the fact that r and

![]() $\varpi $

both asymptote to M along

$\varpi $

both asymptote to M along

![]() $\mathcal H^+$

. The second part involves Taylor expanding

$\mathcal H^+$

. The second part involves Taylor expanding

![]() $\partial _vr$

in u along

$\partial _vr$

in u along

![]() $\mathcal H^+$

to show that there are no trapped or marginally trapped spheres behind

$\mathcal H^+$

to show that there are no trapped or marginally trapped spheres behind

![]() $\mathcal H^+$

. This second part of the argument is reminiscent of the proof of “Israel’s observation” (Proposition 1.1) in [Reference Kehle and Unger48]. We carry out these arguments in Section 8.3.5.

$\mathcal H^+$

. This second part of the argument is reminiscent of the proof of “Israel’s observation” (Proposition 1.1) in [Reference Kehle and Unger48]. We carry out these arguments in Section 8.3.5.

Remark 1.7. These soft arguments, using monotonicity and the wave equation for r, do not directly carry over to the charged scalar field [Reference Kommemi51] or charged Vlasov [Reference Kehle and Unger49] models.

1.2.9 The Aretakis instability on the dynamical geometry

Using the geometric estimates proved in Section 5, the exact conservation law (1.13) is replaced by the “almost conservation law”

Note that the error is integrable in

![]() $\tau $

(again, thanks to going up to

$\tau $

(again, thanks to going up to

![]() $p=3-\delta $

in the hierarchy!) and much better in

$p=3-\delta $

in the hierarchy!) and much better in

![]() $\varepsilon $

than

$\varepsilon $

than

![]() $Y\psi $

. Therefore, integrating this immediately gives (i) of Theorem II. Part (ii) is completely soft and is essentially an immediate consequence of (i). To prove part (iii), we commute the wave equation on the dynamical background with Y and show that the nonlinear error terms are decaying, which results in an estimate entirely analogous to (1.14). The instability of the geometry is obtained by directly inserting this behavior for

$Y\psi $

. Therefore, integrating this immediately gives (i) of Theorem II. Part (ii) is completely soft and is essentially an immediate consequence of (i). To prove part (iii), we commute the wave equation on the dynamical background with Y and show that the nonlinear error terms are decaying, which results in an estimate entirely analogous to (1.14). The instability of the geometry is obtained by directly inserting this behavior for

![]() $\phi $

into the Einstein equations. We do not prove growth of derivatives higher than second order because this would require proving higher order estimates for the geometry, which is not necessary for the proof of Theorem I. These arguments are carried out in Section 9.1.

$\phi $

into the Einstein equations. We do not prove growth of derivatives higher than second order because this would require proving higher order estimates for the geometry, which is not necessary for the proof of Theorem I. These arguments are carried out in Section 9.1.

1.3 The conjectural picture of the local moduli space

Theorem I makes no statement about the regularity (or even connectedness!) of the stable “submanifold”

![]() ${\mathfrak{M}}_{\mathrm{stab}}$

, nor about behavior of solutions arising from data in

${\mathfrak{M}}_{\mathrm{stab}}$

, nor about behavior of solutions arising from data in

![]() ${\mathfrak{M}}\setminus {\mathfrak{M}}_{\mathrm{stab}}$

. In this section, we propose conjectures addressing these issues, motivated by conjectures in [Reference Dafermos, Holzegel, Rodnianski and Taylor27], [Reference Dafermos25], and [Reference Kehle and Unger49] by the second- and third-named authors of the present paper.

${\mathfrak{M}}\setminus {\mathfrak{M}}_{\mathrm{stab}}$

. In this section, we propose conjectures addressing these issues, motivated by conjectures in [Reference Dafermos, Holzegel, Rodnianski and Taylor27], [Reference Dafermos25], and [Reference Kehle and Unger49] by the second- and third-named authors of the present paper.

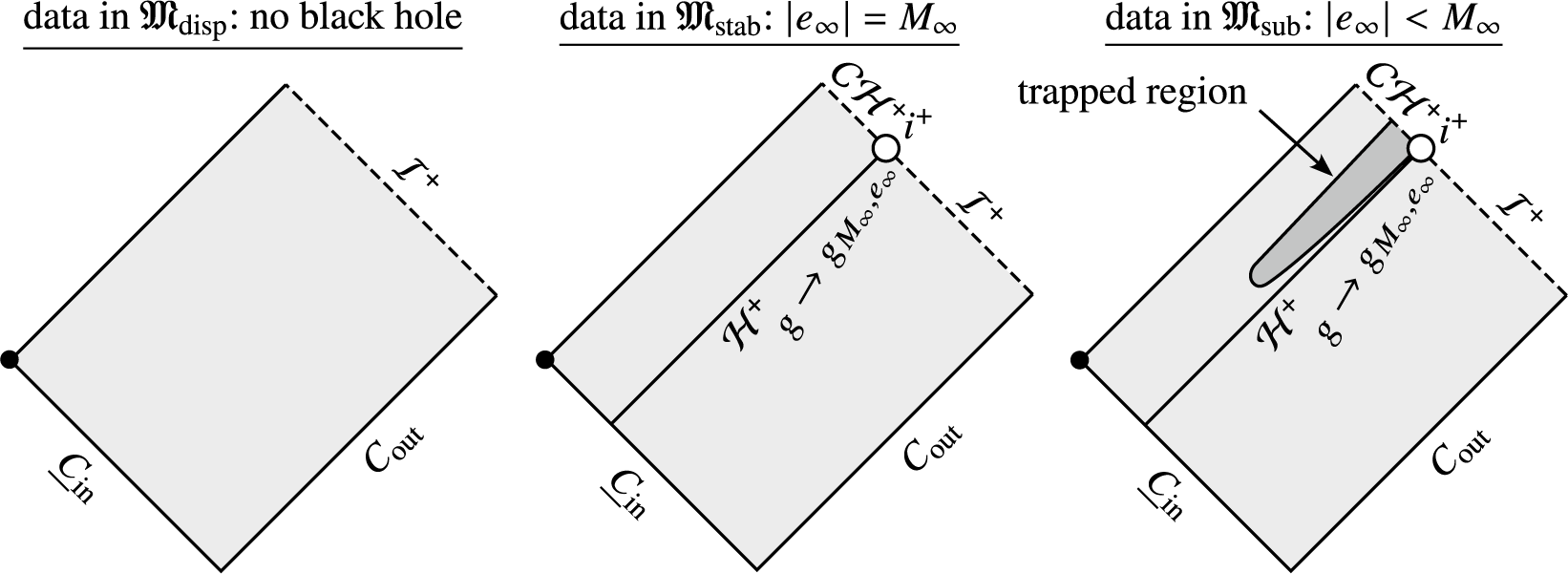

1.3.1 Asymptotically extremal black holes as a locally separating hypersurface between collapse and dispersion

In the following conjectures, we will write the symbol

![]() ${\mathfrak{M}}$

to mean a moduli space of initial data posed “in the same way” as in our Theorem I, but possibly topologized by a different norm than in Section 3.1 below. In particular, it could be that the following conjectures are only true under stronger asymptotic decay assumptions. However, we will always suppose that

${\mathfrak{M}}$

to mean a moduli space of initial data posed “in the same way” as in our Theorem I, but possibly topologized by a different norm than in Section 3.1 below. In particular, it could be that the following conjectures are only true under stronger asymptotic decay assumptions. However, we will always suppose that

![]() ${\mathfrak{M}}$

carries a Banach space structure, so that we have access to the notion of

${\mathfrak{M}}$

carries a Banach space structure, so that we have access to the notion of

![]() $C^1$

submanifolds of

$C^1$

submanifolds of

![]() ${\mathfrak{M}}$

.

${\mathfrak{M}}$

.

For

![]() ${\mathfrak{r}}\in [0,1]$

, we can consider the subset

${\mathfrak{r}}\in [0,1]$

, we can consider the subset

![]() ${\mathfrak{M}}^{\mathfrak{r}}_{\mathrm{stab}}\subset {\mathfrak{M}}$

consisting of initial data which form a black hole with asymptotic parameter ratio

${\mathfrak{M}}^{\mathfrak{r}}_{\mathrm{stab}}\subset {\mathfrak{M}}$

consisting of initial data which form a black hole with asymptotic parameter ratio

![]() $|e|/M_\infty ={\mathfrak{r}}$

, where e is the conserved charge of the solution and

$|e|/M_\infty ={\mathfrak{r}}$