1. Introduction

Diffusive search for hidden targets is critically important for various physical, chemical and biological systems [Reference Dagdug, Peña and Pompa-García21, Reference Lindenberg, Oshanin and Metzler58, Reference Masoliver60, Reference Metzler, Oshanin and Redner62, Reference Redner67, Reference Schuss73]. In the most basic setting, a point-like particle (e.g., a molecule, an ion, a protein, a virus, a bacterium, etc.) undergoes diffusive motion inside a confining environment and searches for an immobile target (e.g., a catalytic site on a solid surface, a channel on a plasma membrane, a specific site on the DNA, a cell, etc.). If the target is hidden in the bulk, it is often called an interior trap or a sink, whereas a target on the boundary is referred to as a reactive patch or an escape window. In both cases, if the target is small, one usually speaks about the narrow escape problem [Reference Holcman and Schuss48, Reference Holcman and Schuss49], bearing in mind the picture of an open window, through which the particle can leave the domain and never return. Most former works were dedicated to finding and even optimising the mean first-passage time (FPT) to a single target or to a given arrangement of multiple targets [Reference Chen and Friedman12, Reference Cheviakov, Ward and Straube16, Reference Grebenkov30, Reference Grebenkov and Oshanin42, Reference Guérin, Dolgushev, Bénichou and Voituriez44, Reference Iyaniwura, Wong, Macdonald and Ward50, Reference Lindsay, Bernoff and Ward59, Reference Pillay, Ward, Peirce and Kolokolnikov65, Reference Schuss, Singer and Holcman74, Reference Singer, Schuss, Holcman and Eisenberg75]. Other relevant characteristics of the diffusive search, such as the whole distribution of the FPT [Reference Bénichou and Voituriez2, Reference Cherry, Lindsay, Navarro Hernández and Quaife13, Reference Godec and Metzler29, Reference Grebenkov, Metzler and Oshanin40, Reference Grebenkov, Metzler and Oshanin41] and Laplacian eigenvalues [Reference Cheviakov and Ward15, Reference Coombs, Straube and Ward20, Reference Kolokolnikov, Titcombe and Ward51], were also studied.

A common limitation of most former works is their emphasis either on a single target or on multiple targets of the same type. In turn, many biochemical applications involve targets of different types. For instance, signal transduction between neurones relies on diffusive search by calcium ions of a sensor protein on the vesicle with neurotransmitters inside the presynaptic bouton [Reference Guerrier and Holcman45, Reference Holcman and Schuss48, Reference Neher and Sakaba63, Reference Reva, DiGregorio and Grebenkov68, Reference Sala and Hernández-Cruz70]. While the sensor protein is the primary target, calcium ions can reversibly bind to buffer molecules inside the confining domain or leave it through calcium channels on its boundary. Both buffer molecules and channels play the role of auxiliary targets that compete for calcium ions and thus allow to control the signal transduction. More generally, the successful reaction of a diffusing particle on a “primary” target may fail due to its eventual capture by other targets or its escape.

When all targets are perfect (i.e., the reaction occurs instantly upon the first arrival), the competition between targets for a diffusing particle is characterised via diffusive fluxes, splitting probabilities and conditional FPTs [Reference Berezhkovskii, Dagdug, Lizunov, Zimmerberg and Bezrukov3, Reference Bressloff5, Reference Chevalier, Bénichou, Meyer and Voituriez14, Reference Delgado, Ward and Coombs22, Reference Felici, Filoche and Sapoval25, Reference Grebenkov32, Reference Grebenkov and Traytak43, Reference Kurella, Tzou, Coombs and Ward54, Reference Traytak76, Reference Traytak and Tachiya77]. In particular, the asymptotic behaviour of these quantities for small interior traps or absorbing patches on the boundary and the dependence on their spatial arrangement have been studied in depth. However, as the targets are not perfectly reactive in most applications [Reference Bressloff6, Reference Collins and Kimball19, Reference Erban and Chapman24, Reference Galanti, Fanelli and Piazza27, Reference Grebenkov31, Reference Grebenkov32, Reference Grebenkov35, Reference Lawley and Keener55, Reference Piazza64, Reference Sano and Tachiya71, Reference Sapoval72], their competition also depends on their reactivities. The role of partially reactive traps, as modelled by a Robin condition, is not nearly as well understood, especially in the two-dimensional case.

The problem becomes even more challenging for more intricate surface reactions, which cannot be described by the conventional Robin boundary condition on targets. We will refer to such targets as imperfect. For instance, the target reactivity can be progressively increased or decreased by encounters with a diffusing particle. Such activation or passivation processes are described within the encounter-based approach [Reference Bressloff7, Reference Bressloff8, Reference Grebenkov33, Reference Grebenkov34, Reference Grebenkov36]. In probabilistic terms, the reaction event occurs when the number of reaction attempts upon each arrival onto the target exceeds some random threshold. The probability distribution of the threshold characterises the reaction mechanism (see details in [Reference Grebenkov34]). For instance, the particular case of the exponential distribution corresponds to a partially reactive target with a constant reactivity, and its probabilistic description is equivalent to solving the diffusion equation with the Robin boundary condition. In turn, other distributions of the threshold describe more intricate surface reactions and involve integral-type boundary conditions. As shown in [Reference Grebenkov34], such PDE problems can be solved by employing spectral expansions based on the Steklov problem (see Sections 4 and 5 for its formulation and basic properties). In particular, the Steklov eigenfunctions turn out to be particularly suitable for dealing with diffusive motion in the confining domain between successive arrivals onto an imperfect target. The peculiar feature of the Steklov problem that distinguishes it from common spectral problems for the Laplacian is that the spectral parameter appears in the boundary condition. Various properties of the Steklov problem have been thoroughly investigated (see [Reference Behrndt and ter Elst1, Reference Colbois, Girouard, Gordon and Sher18, Reference Girouard and Polterovich28, Reference Hassell and Ivrii46, Reference Levitin, Mangoubi and Polterovich56] and references therein). When imperfect targets are located on the inert impenetrable boundary, one needs to combine Steklov and Neumann boundary conditions. Such a mixed Steklov-Neumann problem was already known in hydrodynamics, where it is referred to as the sloshing problem [Reference Fox and Kuttler26, Reference Henrici, Troesch and Wuytack47, Reference Kozlov and Kuznetsov53, Reference Levitin, Parnovski, Polterovich and Sher57]. In the case of a single target, the asymptotic behaviour of its eigenvalues and eigenfunctions in the small-target limit was recently studied [Reference Grebenkov38]. However, the scaling arguments and related analysis from [Reference Grebenkov38] are not directly applicable to the case of multiple targets. The asymptotic behaviour of the spectrum of the mixed Steklov-Neumann problem is thus unknown, despite the importance of its potential applications. Yet another unstudied setting concerns a single imperfect target with the Steklov condition in the presence of multiple escape windows with the Dirichlet condition. A mathematical framework for studying such an escape problem relies on the mixed Steklov-Neumann-Dirichlet problem [Reference Grebenkov37]. To our knowledge, the asymptotic behaviour of its eigenvalues and eigenfunctions in the small-target limit has not been studied previously.

In this paper, we progressively fill the gap between perfect and imperfect targets. In Section 2, we start with the conventional setting of

![]() $N$

absorbing sinks and study their splitting probabilities, i.e., the probability of hitting one sink before any other. This relatively simple setting allows us to introduce, in a didactic way, many notions and tools that will be employed throughout the manuscript. Even though this problem was studied in the past (see [Reference Bressloff5, Reference Chevalier, Bénichou, Meyer and Voituriez14] and references therein), we succeed in improving and generalising some earlier results. Section 3 presents an extension to partially reactive targets, in which the Dirichlet boundary condition is replaced by a Robin condition. We show how partial reactivity effectively reduces the target size. The major contributions of the paper are presented in Sections 4 and 5. In Section 4, we consider the mixed Steklov-Neumann problem for

$N$

absorbing sinks and study their splitting probabilities, i.e., the probability of hitting one sink before any other. This relatively simple setting allows us to introduce, in a didactic way, many notions and tools that will be employed throughout the manuscript. Even though this problem was studied in the past (see [Reference Bressloff5, Reference Chevalier, Bénichou, Meyer and Voituriez14] and references therein), we succeed in improving and generalising some earlier results. Section 3 presents an extension to partially reactive targets, in which the Dirichlet boundary condition is replaced by a Robin condition. We show how partial reactivity effectively reduces the target size. The major contributions of the paper are presented in Sections 4 and 5. In Section 4, we consider the mixed Steklov-Neumann problem for

![]() $N$

imperfect targets. For this novel problem, we obtain the asymptotic behaviour of its eigenvalues and eigenfunctions in the small-target limit. In turn, Section 5 focuses on the mixed Steklov-Neumann-Dirichlet problem, in which one target is imperfect (with Steklov condition), whereas the other targets are perfect (with Dirichlet condition). We apply matched asymptotic expansion techniques to investigate the asymptotic behaviour in the small-target limit. For all considered cases, the accuracy of the derived asymptotic formulas is illustrated on two examples: the case of two patches in an arbitrary domain and the case of

$N$

imperfect targets. For this novel problem, we obtain the asymptotic behaviour of its eigenvalues and eigenfunctions in the small-target limit. In turn, Section 5 focuses on the mixed Steklov-Neumann-Dirichlet problem, in which one target is imperfect (with Steklov condition), whereas the other targets are perfect (with Dirichlet condition). We apply matched asymptotic expansion techniques to investigate the asymptotic behaviour in the small-target limit. For all considered cases, the accuracy of the derived asymptotic formulas is illustrated on two examples: the case of two patches in an arbitrary domain and the case of

![]() $N$

equally spaced patches on the boundary of a disk. Our analytical results are compared with numerical solutions obtained by a finite-element method in Matlab (its home-made implementation for Steklov problems is described in [Reference Chaigneau and Grebenkov11]). In Section 6, we discuss two further extensions of the present analysis: the case of interior targets (or traps), and exterior problems for which diffusion occurs outside a compact set. In this way, we cover a wide variety of settings in which multiple small targets of different types compete for diffusing particles in planar domains. We summarise our main results in Section 7.

$N$

equally spaced patches on the boundary of a disk. Our analytical results are compared with numerical solutions obtained by a finite-element method in Matlab (its home-made implementation for Steklov problems is described in [Reference Chaigneau and Grebenkov11]). In Section 6, we discuss two further extensions of the present analysis: the case of interior targets (or traps), and exterior problems for which diffusion occurs outside a compact set. In this way, we cover a wide variety of settings in which multiple small targets of different types compete for diffusing particles in planar domains. We summarise our main results in Section 7.

2. Splitting probabilities on Dirichlet patches

To introduce the theoretical framework and tools, we begin by revisiting the classical problem of splitting probabilities, which are commonly used to characterise competition between multiple perfectly reactive targets for a diffusing particle. Although this problem has been studied previously (see [Reference Bressloff5, Reference Chevalier, Bénichou, Meyer and Voituriez14] and references therein), we will improve and generalise some earlier results.

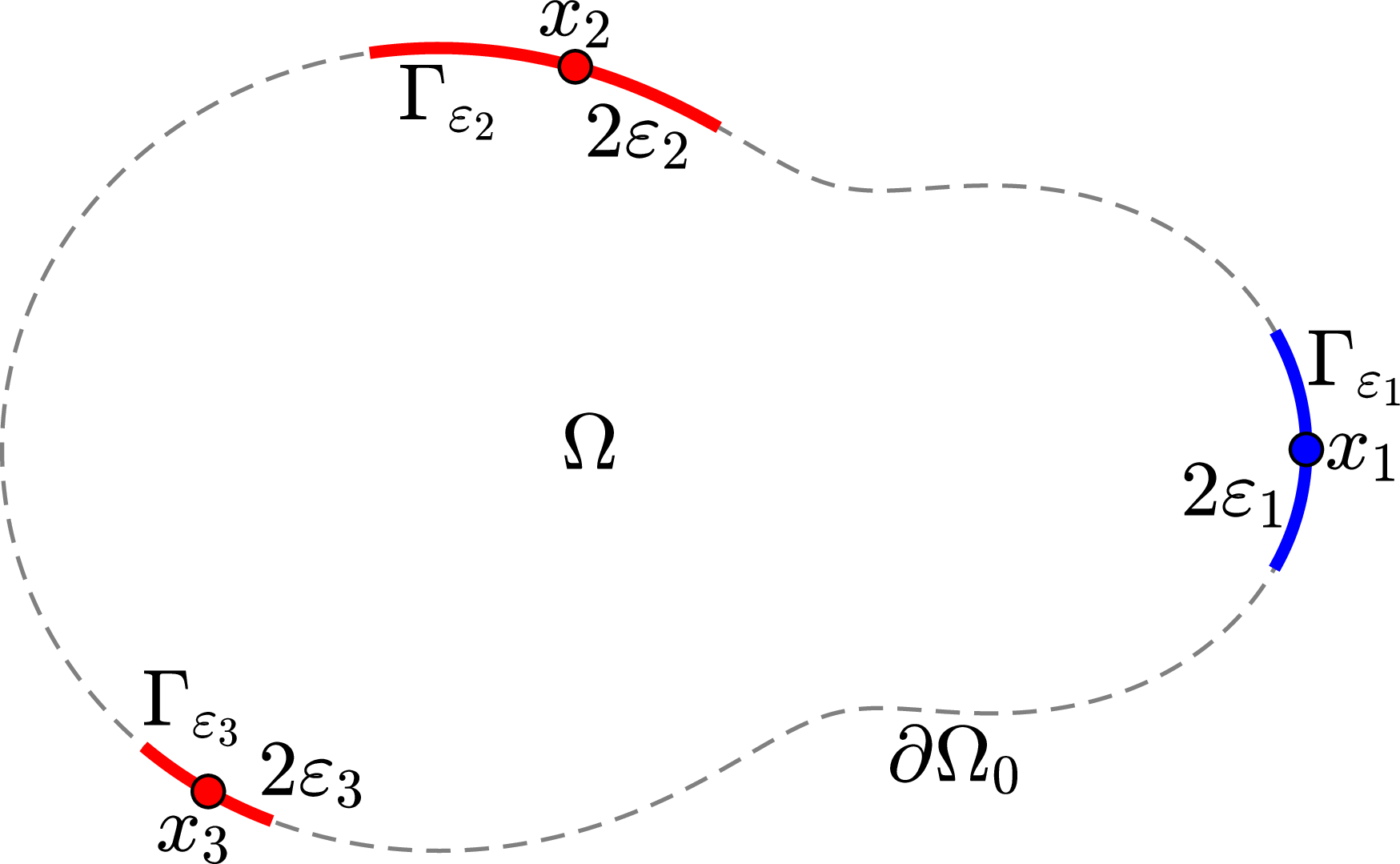

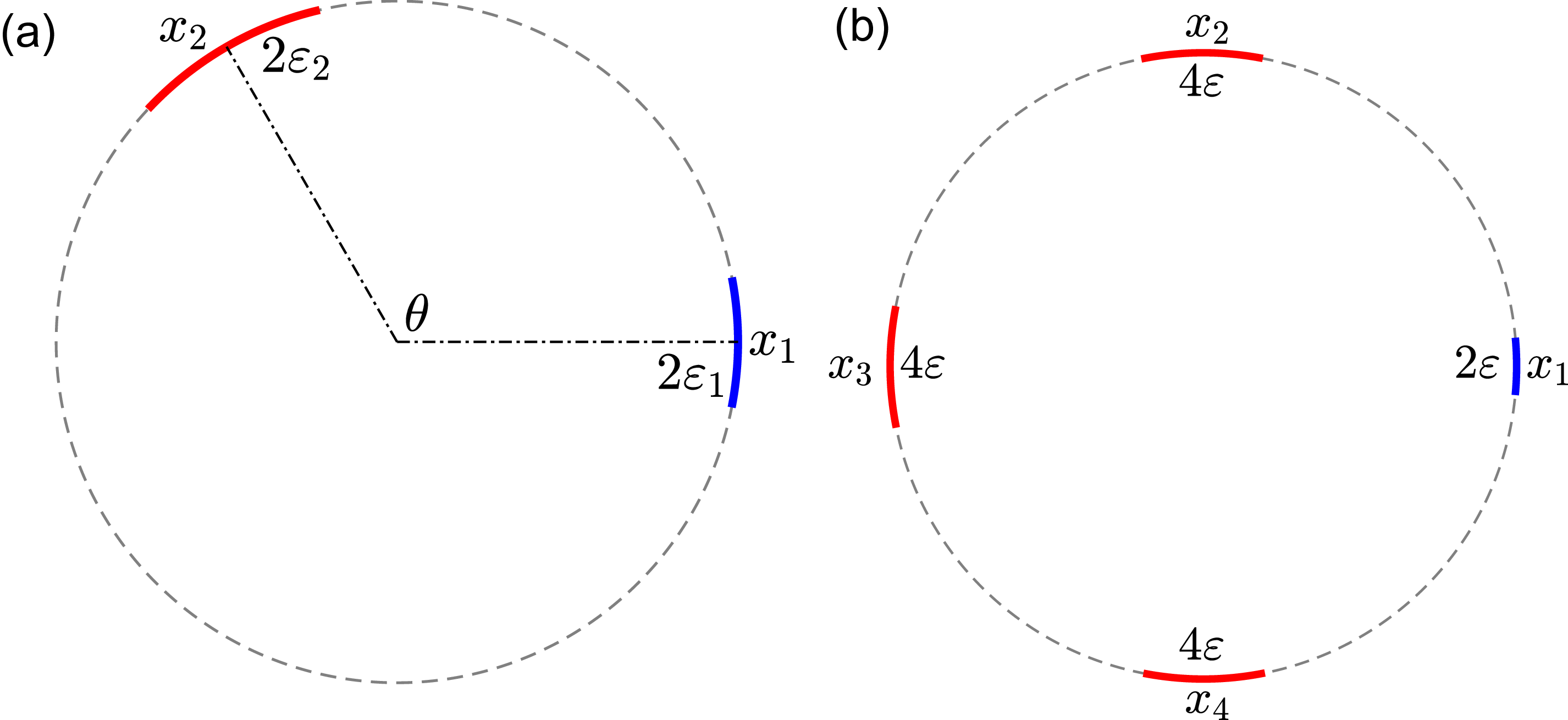

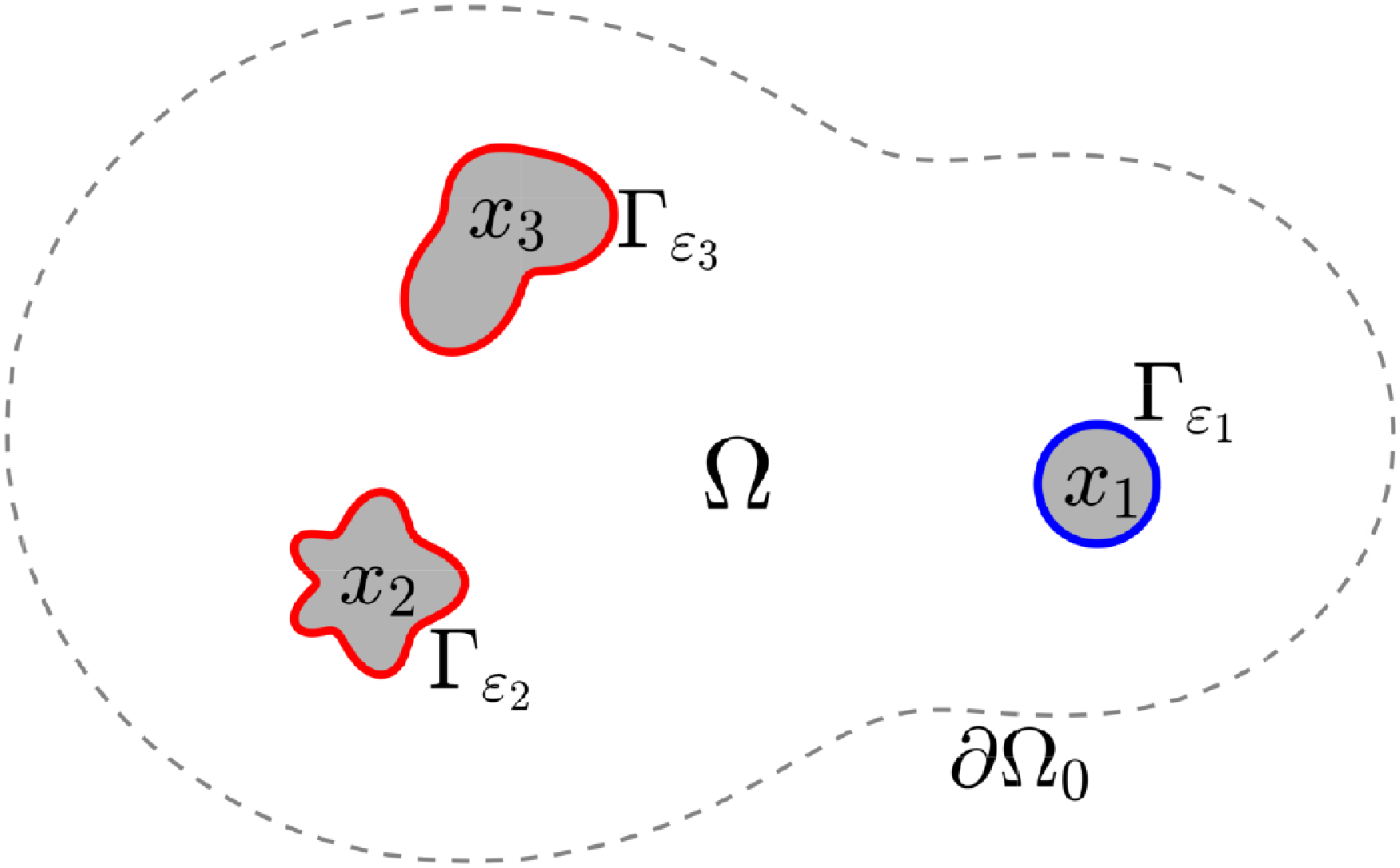

Figure 1. Illustration of a bounded domain

![]() $\Omega \subset {\mathbb{R}}^2$

with a smooth boundary

$\Omega \subset {\mathbb{R}}^2$

with a smooth boundary

![]() $\partial \Omega$

split into three absorbing patches

$\partial \Omega$

split into three absorbing patches

![]() $\Gamma _{\varepsilon _i}$

of length

$\Gamma _{\varepsilon _i}$

of length

![]() $2\varepsilon _i$

(in red and blue), and the remaining reflecting part

$2\varepsilon _i$

(in red and blue), and the remaining reflecting part

![]() $\partial \Omega _0$

(grey dashed line). For a particle starting from a point

$\partial \Omega _0$

(grey dashed line). For a particle starting from a point

![]() ${{\boldsymbol{x}}}\in \Omega$

, the splitting probability

${{\boldsymbol{x}}}\in \Omega$

, the splitting probability

![]() $S_1({{\boldsymbol{x}}})$

is the probability of hitting the blue patch

$S_1({{\boldsymbol{x}}})$

is the probability of hitting the blue patch

![]() $\Gamma _{\varepsilon _1}$

first.

$\Gamma _{\varepsilon _1}$

first.

Let

![]() $\Omega \subset {\mathbb{R}}^2$

be a bounded planar domain with a smooth boundary

$\Omega \subset {\mathbb{R}}^2$

be a bounded planar domain with a smooth boundary

![]() $\partial \Omega$

. Let

$\partial \Omega$

. Let

![]() $\{\Gamma _{\varepsilon _1}, \ldots , \Gamma _{\varepsilon _N}\}$

be

$\{\Gamma _{\varepsilon _1}, \ldots , \Gamma _{\varepsilon _N}\}$

be

![]() $N$

disjoint subsets of the boundary

$N$

disjoint subsets of the boundary

![]() $\partial \Omega$

that represent multiple patches of lengths

$\partial \Omega$

that represent multiple patches of lengths

![]() $2\varepsilon _1, \ldots , 2\varepsilon _N$

that are centred at boundary points

$2\varepsilon _1, \ldots , 2\varepsilon _N$

that are centred at boundary points

![]() ${{\boldsymbol{x}}}_1, \ldots , {{\boldsymbol{x}}}_N$

(each patch

${{\boldsymbol{x}}}_1, \ldots , {{\boldsymbol{x}}}_N$

(each patch

![]() $\Gamma _{\varepsilon _j}$

is connected). The remaining part of the boundary, denoted as

$\Gamma _{\varepsilon _j}$

is connected). The remaining part of the boundary, denoted as

![]() $\partial \Omega _0 = \partial \Omega \backslash (\Gamma _{\varepsilon _1} \cup \cdots \cup \Gamma _{\varepsilon _N})$

, is reflecting (Figure 1). We are interested in the small-target limit when all patches are small and comparable (i.e.,

$\partial \Omega _0 = \partial \Omega \backslash (\Gamma _{\varepsilon _1} \cup \cdots \cup \Gamma _{\varepsilon _N})$

, is reflecting (Figure 1). We are interested in the small-target limit when all patches are small and comparable (i.e.,

![]() $\varepsilon _1 \sim o(1)$

and

$\varepsilon _1 \sim o(1)$

and

![]() $\varepsilon _j/\varepsilon _1 \sim {\mathcal O}(1)$

). We assume that the patches are well-separated in the sense that

$\varepsilon _j/\varepsilon _1 \sim {\mathcal O}(1)$

). We assume that the patches are well-separated in the sense that

![]() $|{{\boldsymbol{x}}}_i - {{\boldsymbol{x}}}_j| = {\mathcal O}(1)$

for all

$|{{\boldsymbol{x}}}_i - {{\boldsymbol{x}}}_j| = {\mathcal O}(1)$

for all

![]() $i\ne j$

.

$i\ne j$

.

In this section, we consider that all patches

![]() $\Gamma _{\varepsilon _j}$

are absorbing sinks (i.e., perfectly reactive targets). For a particle started from a point

$\Gamma _{\varepsilon _j}$

are absorbing sinks (i.e., perfectly reactive targets). For a particle started from a point

![]() ${{\boldsymbol{x}}} \in \Omega$

, we aim at determining the splitting probability

${{\boldsymbol{x}}} \in \Omega$

, we aim at determining the splitting probability

![]() $S_k({{\boldsymbol{x}}})$

(

$S_k({{\boldsymbol{x}}})$

(

![]() $k = 1,\ldots ,N$

), i.e., the probability of the arrival onto the Dirichlet patch

$k = 1,\ldots ,N$

), i.e., the probability of the arrival onto the Dirichlet patch

![]() $\Gamma _{\varepsilon _k}$

before hitting any other patch. This probability satisfies the boundary value problem (BVP)

$\Gamma _{\varepsilon _k}$

before hitting any other patch. This probability satisfies the boundary value problem (BVP)

where

![]() $\Delta$

is the Laplacian,

$\Delta$

is the Laplacian,

![]() $\partial _n$

is the normal derivative oriented outward to the domain

$\partial _n$

is the normal derivative oriented outward to the domain

![]() $\Omega$

, and

$\Omega$

, and

![]() $\delta _{j,k}$

is the Kronecker symbol. In the analysis below,

$\delta _{j,k}$

is the Kronecker symbol. In the analysis below,

![]() $k\in \lbrace {1,\ldots ,N\rbrace }$

is fixed. In the small-target limit

$k\in \lbrace {1,\ldots ,N\rbrace }$

is fixed. In the small-target limit

![]() $\varepsilon _j\to 0$

for each

$\varepsilon _j\to 0$

for each

![]() $j\in \lbrace {1,\ldots ,N\rbrace }$

, we will use the method of matched asymptotic expansions for problems with logarithmic interactions [Reference Ward, Henshaw and Keller78] to approximate solutions to (2.1) that are accurate to all powers of

$j\in \lbrace {1,\ldots ,N\rbrace }$

, we will use the method of matched asymptotic expansions for problems with logarithmic interactions [Reference Ward, Henshaw and Keller78] to approximate solutions to (2.1) that are accurate to all powers of

![]() $1/\ln (\varepsilon _j)$

.

$1/\ln (\varepsilon _j)$

.

2.1. Inner solutions

The inner solution near each Dirichlet patch

![]() $\Gamma _{\varepsilon _j}$

can be found by introducing the local coordinates

$\Gamma _{\varepsilon _j}$

can be found by introducing the local coordinates

![]() ${\boldsymbol{y}} = \varepsilon _j^{-1} \textbf{Q}_j ({{\boldsymbol{x}}}-{{\boldsymbol{x}}}_j)$

, where

${\boldsymbol{y}} = \varepsilon _j^{-1} \textbf{Q}_j ({{\boldsymbol{x}}}-{{\boldsymbol{x}}}_j)$

, where

![]() $\textbf{Q}_j$

is an appropriate rotation matrix to restrict

$\textbf{Q}_j$

is an appropriate rotation matrix to restrict

![]() ${\boldsymbol{y}} = (y_1,y_2)$

to the upper-half-plane

${\boldsymbol{y}} = (y_1,y_2)$

to the upper-half-plane

![]() ${\mathbb{H}}_2 = {\mathbb{R}} \times {\mathbb{R}}_+$

(the matrix

${\mathbb{H}}_2 = {\mathbb{R}} \times {\mathbb{R}}_+$

(the matrix

![]() $\textbf{Q}_j$

plays no role since

$\textbf{Q}_j$

plays no role since

![]() $\textbf{Q}_j^\dagger \textbf{Q}_j = {\textbf{I}}$

and

$\textbf{Q}_j^\dagger \textbf{Q}_j = {\textbf{I}}$

and

![]() $|{\boldsymbol{y}}| = \varepsilon _j^{-1} |{{\boldsymbol{x}}}-{{\boldsymbol{x}}}_j|$

). We look for an inner solution near the patch

$|{\boldsymbol{y}}| = \varepsilon _j^{-1} |{{\boldsymbol{x}}}-{{\boldsymbol{x}}}_j|$

). We look for an inner solution near the patch

![]() $\Gamma _{\varepsilon _j}$

in the form

$\Gamma _{\varepsilon _j}$

in the form

where

![]() $A_j$

is an unknown constant, and

$A_j$

is an unknown constant, and

![]() $g_\infty (\,{\boldsymbol{y}})$

is the Green’s function satisfying the canonical BVP given by

$g_\infty (\,{\boldsymbol{y}})$

is the Green’s function satisfying the canonical BVP given by

(the subscript

![]() $\infty$

highlights infinite reactivity of the perfect patch, see below). The exact solution of this classical problem is given in Appendix A for completeness. The analysis below will require only the knowledge of the asymptotic behaviour of

$\infty$

highlights infinite reactivity of the perfect patch, see below). The exact solution of this classical problem is given in Appendix A for completeness. The analysis below will require only the knowledge of the asymptotic behaviour of

![]() $g_\infty (\,{\boldsymbol{y}})$

at infinity. We recall that the constant term in this behaviour,

$g_\infty (\,{\boldsymbol{y}})$

at infinity. We recall that the constant term in this behaviour,

is determined by the logarithmic capacity

![]() $d$

of the interval

$d$

of the interval

![]() $({-}1,1)$

, which is simply

$({-}1,1)$

, which is simply

![]() $d={1/2}$

. Now putting

$d={1/2}$

. Now putting

![]() ${\boldsymbol{y}} = \varepsilon _j^{-1} \textbf{Q}_j ({{\boldsymbol{x}}}-{{\boldsymbol{x}}}_j)$

, we get that the far-field behaviour of the inner solution is

${\boldsymbol{y}} = \varepsilon _j^{-1} \textbf{Q}_j ({{\boldsymbol{x}}}-{{\boldsymbol{x}}}_j)$

, we get that the far-field behaviour of the inner solution is

Setting

we rewrite this far-field behaviour, for each

![]() $j \in \lbrace {1,\ldots ,N\rbrace }$

, as

$j \in \lbrace {1,\ldots ,N\rbrace }$

, as

2.2. Outer solution and matching conditions

Now, we consider the outer problem for

![]() $S_k({{\boldsymbol{x}}})$

given by

$S_k({{\boldsymbol{x}}})$

given by

To find this solution, we introduce the surface Neumann Green’s function

![]() $G({{\boldsymbol{x}}},{\boldsymbol \xi })$

, which satisfies

$G({{\boldsymbol{x}}},{\boldsymbol \xi })$

, which satisfies

where

![]() $|\Omega |$

is the area of

$|\Omega |$

is the area of

![]() $\Omega$

, and

$\Omega$

, and

![]() $R({\boldsymbol \xi })$

is the regular part of

$R({\boldsymbol \xi })$

is the regular part of

![]() $G({{\boldsymbol{x}}},{\boldsymbol \xi })$

, defined by

$G({{\boldsymbol{x}}},{\boldsymbol \xi })$

, defined by

The formulation in (2.9) is equivalent to imposing that

![]() $\partial _n G=\delta ({{\boldsymbol{x}}}-{\boldsymbol \xi })$

on

$\partial _n G=\delta ({{\boldsymbol{x}}}-{\boldsymbol \xi })$

on

![]() $\partial \Omega$

where

$\partial \Omega$

where

![]() ${\boldsymbol \xi }\in \partial \Omega$

.

${\boldsymbol \xi }\in \partial \Omega$

.

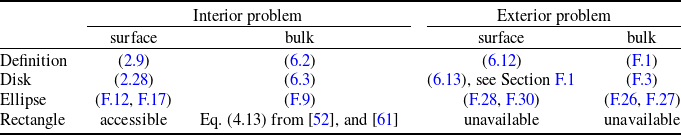

Remark 1.

For a disk,

![]() $G$

and

$G$

and

![]() $R$

are known analytically from [Reference Kolokolnikov, Titcombe and Ward51] and [Reference Pillay, Ward, Peirce and Kolokolnikov65] (see (2.28) below). For a square domain, they can be represented in terms of rapidly converging infinite series representations (see Section 3.3 of [Reference Pillay, Ward, Peirce and Kolokolnikov65]). Similar representations can be obtained for rectangles and ellipses from the results for the interior Neumann Green’s function in Section 4.2 of [Reference Kolokolnikov, Ward and Wei52] and in Section 5 of [Reference Iyaniwura, Wong, Macdonald and Ward50], respectively, by allowing the interior source point to tend to the domain boundary (see Section F.2 for this derivation for an ellipse and Table F1). A numerical method to compute

$R$

are known analytically from [Reference Kolokolnikov, Titcombe and Ward51] and [Reference Pillay, Ward, Peirce and Kolokolnikov65] (see (2.28) below). For a square domain, they can be represented in terms of rapidly converging infinite series representations (see Section 3.3 of [Reference Pillay, Ward, Peirce and Kolokolnikov65]). Similar representations can be obtained for rectangles and ellipses from the results for the interior Neumann Green’s function in Section 4.2 of [Reference Kolokolnikov, Ward and Wei52] and in Section 5 of [Reference Iyaniwura, Wong, Macdonald and Ward50], respectively, by allowing the interior source point to tend to the domain boundary (see Section F.2 for this derivation for an ellipse and Table F1). A numerical method to compute

![]() $G$

and

$G$

and

![]() $R$

in arbitrary planar domains is described in Section 3.3 of [Reference Pillay, Ward, Peirce and Kolokolnikov65].

$R$

in arbitrary planar domains is described in Section 3.3 of [Reference Pillay, Ward, Peirce and Kolokolnikov65].

The divergence theorem applied to Eq. (2.8) yields

Under this condition, the solution to Eq. (2.8) can be written as the linear combination

where

![]() $\chi _k$

is a constant to be found. Matching the inner and outer asymptotic expansions as

$\chi _k$

is a constant to be found. Matching the inner and outer asymptotic expansions as

![]() ${{\boldsymbol{x}}}\to {{\boldsymbol{x}}}_j$

gives

${{\boldsymbol{x}}}\to {{\boldsymbol{x}}}_j$

gives

\begin{equation} A_j + \nu _j\left[A_j R_j + \sum \limits _{i=1 \atop i\ne j}^N G_{j,i} A_i\right] = \chi _k \nu _j - \nu _k \delta _{j,k}, \end{equation}

\begin{equation} A_j + \nu _j\left[A_j R_j + \sum \limits _{i=1 \atop i\ne j}^N G_{j,i} A_i\right] = \chi _k \nu _j - \nu _k \delta _{j,k}, \end{equation}

for

![]() $j\in \lbrace {1,\ldots ,N\rbrace }$

, where we have defined

$j\in \lbrace {1,\ldots ,N\rbrace }$

, where we have defined

Together with the compatibility condition (2.11), we obtain a system of

![]() $N+1$

linear equations that determine the unknown coefficients

$N+1$

linear equations that determine the unknown coefficients

![]() $A_1, \ldots ,A_N$

and

$A_1, \ldots ,A_N$

and

![]() $\chi _k$

.

$\chi _k$

.

2.3. Matrix reformulation and general solution

To proceed, we introduce the following vectors and matrices of sizes

![]() $N\times 1$

and

$N\times 1$

and

![]() $N\times N$

:

$N\times N$

:

\begin{align} {\textbf{e}} = \left (\begin{array}{c} 1 \\ 1 \\ \cdots \\ 1 \\ \end{array}\right ), \quad {\boldsymbol \nu } = \left (\begin{array}{c@{\quad}c@{\quad}c@{\quad}c} \nu _1 & 0 & \cdots & 0 \\ 0 & \nu _2 & \cdots & 0 \\ \cdots &\cdots &\cdots &\cdots \\ 0 & 0 &\cdots & \nu _N \\ \end{array}\right ), \quad {\textbf{G}} = \left (\begin{array}{c@{\quad}c@{\quad}c@{\quad}c} R_1 & G_{1,2} & \cdots & G_{1,N} \\ G_{2,1} & R_2 & \cdots & G_{2,N} \\ \cdots &\cdots &\cdots &\cdots \\ G_{N,1} & G_{N,2} &\cdots & R_N \\ \end{array}\right )\, \quad {\textbf{e}}_k = \left (\begin{array}{c} 0 \\ 1 \\ \cdots \\ 0 \\ \end{array}\right ),\nonumber\\[4pt] \end{align}

\begin{align} {\textbf{e}} = \left (\begin{array}{c} 1 \\ 1 \\ \cdots \\ 1 \\ \end{array}\right ), \quad {\boldsymbol \nu } = \left (\begin{array}{c@{\quad}c@{\quad}c@{\quad}c} \nu _1 & 0 & \cdots & 0 \\ 0 & \nu _2 & \cdots & 0 \\ \cdots &\cdots &\cdots &\cdots \\ 0 & 0 &\cdots & \nu _N \\ \end{array}\right ), \quad {\textbf{G}} = \left (\begin{array}{c@{\quad}c@{\quad}c@{\quad}c} R_1 & G_{1,2} & \cdots & G_{1,N} \\ G_{2,1} & R_2 & \cdots & G_{2,N} \\ \cdots &\cdots &\cdots &\cdots \\ G_{N,1} & G_{N,2} &\cdots & R_N \\ \end{array}\right )\, \quad {\textbf{e}}_k = \left (\begin{array}{c} 0 \\ 1 \\ \cdots \\ 0 \\ \end{array}\right ),\nonumber\\[4pt] \end{align}

where

![]() $1$

stands on the

$1$

stands on the

![]() $k$

-th row of the vector

$k$

-th row of the vector

![]() ${\textbf{e}}_k$

.

${\textbf{e}}_k$

.

In terms of this notation, the system (2.13) is written in matrix form as

Applying

![]() ${\textbf{e}}^\dagger$

on the left, we isolate

${\textbf{e}}^\dagger$

on the left, we isolate

![]() $\chi _k$

as

$\chi _k$

as

where we used

![]() ${\textbf{e}}^\dagger {\textbf{A}} = 0$

due to Eq. (2.11), and defined

${\textbf{e}}^\dagger {\textbf{A}} = 0$

due to Eq. (2.11), and defined

Eliminating

![]() $\chi _k$

from Eq. (2.16), we get a matrix equation for

$\chi _k$

from Eq. (2.16), we get a matrix equation for

![]() $\textbf{A}$

given by

$\textbf{A}$

given by

By introducing the matrices

![]() ${\textbf{M}}_0$

and

${\textbf{M}}_0$

and

![]() $\textbf{E}$

by

$\textbf{E}$

by

the solution to Eq. (2.19) is

where

![]() ${\textbf{M}}_0^{-1}$

is the inverse of

${\textbf{M}}_0^{-1}$

is the inverse of

![]() ${\textbf{M}}_0$

. In fact, in the small-target limit, all

${\textbf{M}}_0$

. In fact, in the small-target limit, all

![]() $\nu _j \ll 1$

so that

$\nu _j \ll 1$

so that

![]() ${\textbf{M}}_0$

is a small perturbation of the identity matrix

${\textbf{M}}_0$

is a small perturbation of the identity matrix

![]() $\textbf{I}$

and is thus invertible. Once the coefficients

$\textbf{I}$

and is thus invertible. Once the coefficients

![]() $A_i$

are found, the constant

$A_i$

are found, the constant

![]() $\chi _k$

follows from Eq. (2.17). As a consequence, the splitting probability

$\chi _k$

follows from Eq. (2.17). As a consequence, the splitting probability

![]() $S_k({{\boldsymbol{x}}})$

is fully determined via the representation (2.12). This is the main result of this section. The shape of the confining domain

$S_k({{\boldsymbol{x}}})$

is fully determined via the representation (2.12). This is the main result of this section. The shape of the confining domain

![]() $\Omega$

and the arrangement of Dirichlet patches are captured by the matrix

$\Omega$

and the arrangement of Dirichlet patches are captured by the matrix

![]() $\textbf{G}$

, whereas the sizes of patches are accounted for via the matrix

$\textbf{G}$

, whereas the sizes of patches are accounted for via the matrix

![]() $\boldsymbol \nu$

. When the surface Neumann Green’s function is known analytically, a numerical computation of the coefficients

$\boldsymbol \nu$

. When the surface Neumann Green’s function is known analytically, a numerical computation of the coefficients

![]() $A_i$

and

$A_i$

and

![]() $\chi _k$

is fast, at least if the number of targets is not too large. We emphasise that the solution

$\chi _k$

is fast, at least if the number of targets is not too large. We emphasise that the solution

![]() $\textbf{A}$

in (2.21) to the linear system (2.19) has accounted for all logarithmic correction terms in the asymptotic expansion of the splitting probability. This technique for effectively summing what otherwise would be an infinite logarithmic expansion in powers of

$\textbf{A}$

in (2.21) to the linear system (2.19) has accounted for all logarithmic correction terms in the asymptotic expansion of the splitting probability. This technique for effectively summing what otherwise would be an infinite logarithmic expansion in powers of

![]() $\nu _k$

was developed in [Reference Ward, Henshaw and Keller78], and has been used in other contexts (see [Reference Coombs, Straube and Ward20, Reference Kurella, Tzou, Coombs and Ward54, Reference Pillay, Ward, Peirce and Kolokolnikov65]).

$\nu _k$

was developed in [Reference Ward, Henshaw and Keller78], and has been used in other contexts (see [Reference Coombs, Straube and Ward20, Reference Kurella, Tzou, Coombs and Ward54, Reference Pillay, Ward, Peirce and Kolokolnikov65]).

We further emphasise that Eq. (2.12) is only applicable in the outer region, i.e., when

![]() $|{{\boldsymbol{x}}}-{{\boldsymbol{x}}}_j| \gg {\mathcal O}(\varepsilon _j)$

for all

$|{{\boldsymbol{x}}}-{{\boldsymbol{x}}}_j| \gg {\mathcal O}(\varepsilon _j)$

for all

![]() $j \in \lbrace {1,\ldots ,N\rbrace }$

. In turn, if the starting point

$j \in \lbrace {1,\ldots ,N\rbrace }$

. In turn, if the starting point

![]() ${\boldsymbol{x}}$

is too close to

${\boldsymbol{x}}$

is too close to

![]() ${{\boldsymbol{x}}}_j$

, this asymptotic formula may give wrong values (e.g., negative or exceeding

${{\boldsymbol{x}}}_j$

, this asymptotic formula may give wrong values (e.g., negative or exceeding

![]() $1$

). In practice, the outer solution can be capped by

$1$

). In practice, the outer solution can be capped by

![]() $0$

and

$0$

and

![]() $1$

to avoid such invalid values, i.e., one can use

$1$

to avoid such invalid values, i.e., one can use

![]() $\max \{0, \min \{1, S_k({{\boldsymbol{x}}})\}\}$

instead of

$\max \{0, \min \{1, S_k({{\boldsymbol{x}}})\}\}$

instead of

![]() $S_k({{\boldsymbol{x}}})$

. We remark that if an accurate approximation of the splitting probability is needed near the patch, one has to use the corresponding inner solution.

$S_k({{\boldsymbol{x}}})$

. We remark that if an accurate approximation of the splitting probability is needed near the patch, one has to use the corresponding inner solution.

We also note that the constant

![]() $\chi _k$

can be interpreted as the volume-averaged splitting probability. In fact, if the starting point

$\chi _k$

can be interpreted as the volume-averaged splitting probability. In fact, if the starting point

![]() ${\boldsymbol{x}}$

is not fixed but uniformly distributed in

${\boldsymbol{x}}$

is not fixed but uniformly distributed in

![]() $\Omega$

, the average over the starting point yields

$\Omega$

, the average over the starting point yields

where we used

![]() $\int _{\Omega } G({{\boldsymbol{x}}},{{\boldsymbol{x}}}_i)\, d{{\boldsymbol{x}}}=0$

.

$\int _{\Omega } G({{\boldsymbol{x}}},{{\boldsymbol{x}}}_i)\, d{{\boldsymbol{x}}}=0$

.

2.4. Example of two patches

In the case of two targets (

![]() $N = 2$

), the matrix

$N = 2$

), the matrix

![]() ${\textbf{M}}_0$

from Eq. (2.20) reads

${\textbf{M}}_0$

from Eq. (2.20) reads

\begin{equation} {\textbf{M}}_0 = {\textbf{I}} + \gamma \left (\begin{array}{c@{\quad}c} R_1 - G_{1,2} & G_{1,2} - R_2 \\[4pt] G_{1,2} - R_1 & R_2 - G_{1,2} \\ \end{array}\right ), \end{equation}

\begin{equation} {\textbf{M}}_0 = {\textbf{I}} + \gamma \left (\begin{array}{c@{\quad}c} R_1 - G_{1,2} & G_{1,2} - R_2 \\[4pt] G_{1,2} - R_1 & R_2 - G_{1,2} \\ \end{array}\right ), \end{equation}

where

![]() $\gamma = \nu _1 \nu _2/(\nu _1 + \nu _2)$

. The inverse of this matrix is

$\gamma = \nu _1 \nu _2/(\nu _1 + \nu _2)$

. The inverse of this matrix is

\begin{equation} {\textbf{M}}_0^{-1} = \frac {1}{1 + \gamma (R_1 + R_2 - 2G_{1,2})} \left ( {\textbf{I}} + \gamma \left (\begin{array}{c@{\quad}c} R_2 - G_{1,2} & R_2 -G_{1,2} \\[4pt] R_1 -G_{1,2} & R_1 - G_{1,2} \\ \end{array}\right ) \right ) . \end{equation}

\begin{equation} {\textbf{M}}_0^{-1} = \frac {1}{1 + \gamma (R_1 + R_2 - 2G_{1,2})} \left ( {\textbf{I}} + \gamma \left (\begin{array}{c@{\quad}c} R_2 - G_{1,2} & R_2 -G_{1,2} \\[4pt] R_1 -G_{1,2} & R_1 - G_{1,2} \\ \end{array}\right ) \right ) . \end{equation}

Substituting this expression into Eq. (2.21), we find for

![]() $k = 1$

that

$k = 1$

that

Then, by using Eq. (2.17) we determine

![]() $\chi _1$

as

$\chi _1$

as

which can be further simplified as

For instance, if

![]() $\Omega$

is the unit disk, the surface Neumann Green’s function is well known [Reference Pillay, Ward, Peirce and Kolokolnikov65]:

$\Omega$

is the unit disk, the surface Neumann Green’s function is well known [Reference Pillay, Ward, Peirce and Kolokolnikov65]:

Substitution of these expressions into Eqs. (2.25, 2.27) yields

and we conclude that

We can easily check that

![]() $S_1({{\boldsymbol{x}}})$

approaches

$S_1({{\boldsymbol{x}}})$

approaches

![]() $0$

[resp.,

$0$

[resp.,

![]() $1$

] as

$1$

] as

![]() $\varepsilon _1\to 0$

[resp.,

$\varepsilon _1\to 0$

[resp.,

![]() $\varepsilon _2 \to 0$

], as expected.

$\varepsilon _2 \to 0$

], as expected.

In the special case of two identical targets,

![]() $\nu _1 = \nu _2 = \nu$

, one has

$\nu _1 = \nu _2 = \nu$

, one has

![]() $\chi _1 = 1/2$

and

$\chi _1 = 1/2$

and

![]() $A_2 = 1/(2/\nu + 2\ln |{{\boldsymbol{x}}}_1-{{\boldsymbol{x}}}_2|)$

so that

$A_2 = 1/(2/\nu + 2\ln |{{\boldsymbol{x}}}_1-{{\boldsymbol{x}}}_2|)$

so that

We remark that if we were to expand the denominator of the second term into a Taylor series in powers of

![]() $\nu \ll 1$

up to

$\nu \ll 1$

up to

![]() ${\mathcal O}(\nu ^2)$

, we would recover the truncated approximation given in Eq. (98) from [Reference Chevalier, Bénichou, Meyer and Voituriez14]. However, as

${\mathcal O}(\nu ^2)$

, we would recover the truncated approximation given in Eq. (98) from [Reference Chevalier, Bénichou, Meyer and Voituriez14]. However, as

![]() $\nu = -1/\ln (\varepsilon /2)$

is not necessarily small enough, our new result Eq. (2.31) that incorporates all logarithmic terms is preferable to using the previous truncated approximation from [Reference Chevalier, Bénichou, Meyer and Voituriez14].

$\nu = -1/\ln (\varepsilon /2)$

is not necessarily small enough, our new result Eq. (2.31) that incorporates all logarithmic terms is preferable to using the previous truncated approximation from [Reference Chevalier, Bénichou, Meyer and Voituriez14].

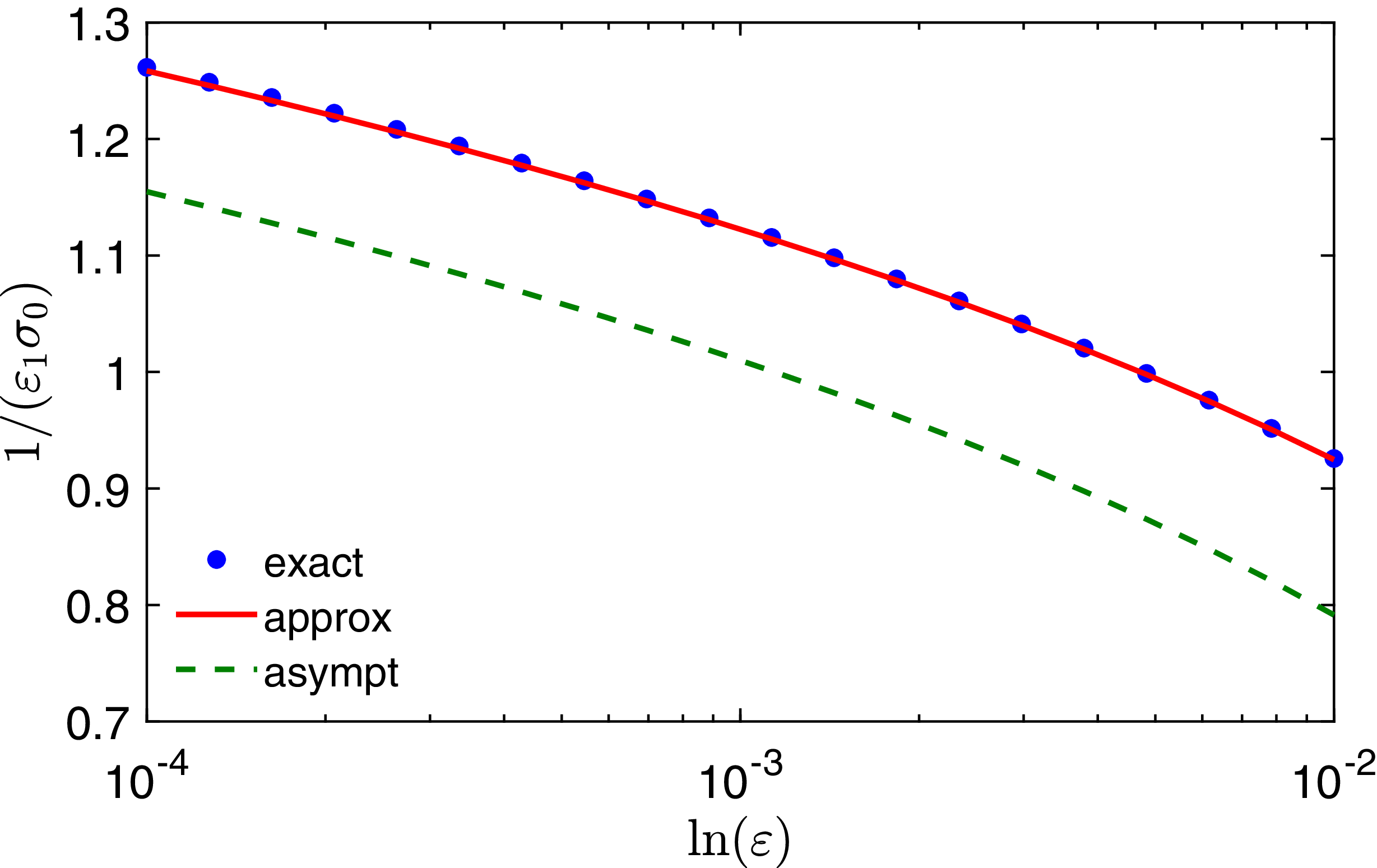

Figure 2 illustrates the splitting probability

![]() $S_1({{\boldsymbol{x}}})$

from Eq. (2.30). As explained earlier, we plot the capped version of this quantity,

$S_1({{\boldsymbol{x}}})$

from Eq. (2.30). As explained earlier, we plot the capped version of this quantity,

![]() $\max \{0, \min \{1, S_1({{\boldsymbol{x}}})\}\}$

, to avoid invalid values near two patches. Expectedly,

$\max \{0, \min \{1, S_1({{\boldsymbol{x}}})\}\}$

, to avoid invalid values near two patches. Expectedly,

![]() $S_1({{\boldsymbol{x}}})$

increases as

$S_1({{\boldsymbol{x}}})$

increases as

![]() ${\boldsymbol{x}}$

gets closer to the first patch (red arc) and decreases as

${\boldsymbol{x}}$

gets closer to the first patch (red arc) and decreases as

![]() ${\boldsymbol{x}}$

gets closer to the second patch (blue arc). However, as the outer solution (2.30) is not applicable in the vicinity of these patches, we can observe some discrepancy, e.g.,

${\boldsymbol{x}}$

gets closer to the second patch (blue arc). However, as the outer solution (2.30) is not applicable in the vicinity of these patches, we can observe some discrepancy, e.g.,

![]() $S_1({{\boldsymbol{x}}})$

does not vanish on the second patch, as it should. To amend this discrepancy, we can use the inner solution when

$S_1({{\boldsymbol{x}}})$

does not vanish on the second patch, as it should. To amend this discrepancy, we can use the inner solution when

![]() $|{{\boldsymbol{x}}}-{{\boldsymbol{x}}}_j| \lesssim \varepsilon _j$

.

$|{{\boldsymbol{x}}}-{{\boldsymbol{x}}}_j| \lesssim \varepsilon _j$

.

Figure 2. Splitting probability

![]() $S_1({{\boldsymbol{x}}})$

, given by Eq. (2.30), for the unit disk with two Dirichlet patches of length

$S_1({{\boldsymbol{x}}})$

, given by Eq. (2.30), for the unit disk with two Dirichlet patches of length

![]() $2\varepsilon _1 = 0.2$

(red) and

$2\varepsilon _1 = 0.2$

(red) and

![]() $2\varepsilon _2 = 0.4$

(blue). Note that

$2\varepsilon _2 = 0.4$

(blue). Note that

![]() $S_1({{\boldsymbol{x}}})$

was capped by

$S_1({{\boldsymbol{x}}})$

was capped by

![]() $0$

and

$0$

and

![]() $1$

, i.e., we plotted

$1$

, i.e., we plotted

![]() $\max \{0, \min \{1, S_1({{\boldsymbol{x}}})\}\}$

.

$\max \{0, \min \{1, S_1({{\boldsymbol{x}}})\}\}$

.

2.5. Example of equally spaced identical patches on the boundary of the unit disk

If there are

![]() $N$

identical targets, one has

$N$

identical targets, one has

![]() $\nu _j = \nu$

so that

$\nu _j = \nu$

so that

![]() ${\boldsymbol \nu } = \nu {\textbf{I}}$

,

${\boldsymbol \nu } = \nu {\textbf{I}}$

,

![]() $\bar {\nu } = N \nu$

, and thus

$\bar {\nu } = N \nu$

, and thus

![]() ${\textbf{M}}_0 = {\textbf{I}} + \nu ({\textbf{I}} - {\textbf{E}}/N) {\textbf{G}}$

from Eq. (2.20). Moreover, if the patches are equally spaced on the boundary of the unit circle, the matrix

${\textbf{M}}_0 = {\textbf{I}} + \nu ({\textbf{I}} - {\textbf{E}}/N) {\textbf{G}}$

from Eq. (2.20). Moreover, if the patches are equally spaced on the boundary of the unit circle, the matrix

![]() $\textbf{G}$

defined in Eq. (2.15) is circulant and symmetric. As a consequence, its eigenvectors can be written as

$\textbf{G}$

defined in Eq. (2.15) is circulant and symmetric. As a consequence, its eigenvectors can be written as

where

![]() $\omega = e^{2\pi i/N}$

, and the transposition

$\omega = e^{2\pi i/N}$

, and the transposition

![]() $\dagger$

now denotes the Hermitian conjugate. Upon taking the real and imaginary parts of

$\dagger$

now denotes the Hermitian conjugate. Upon taking the real and imaginary parts of

![]() $\textbf{q}_j$

, the resulting real-valued eigenvectors form an orthonormal basis in

$\textbf{q}_j$

, the resulting real-valued eigenvectors form an orthonormal basis in

![]() ${\mathbb{R}}^{N}$

since

${\mathbb{R}}^{N}$

since

![]() $\textbf{G}$

is symmetric. Let us denote by

$\textbf{G}$

is symmetric. Let us denote by

![]() $\kappa _j$

the associated eigenvalues of

$\kappa _j$

the associated eigenvalues of

![]() $\textbf{G}$

:

$\textbf{G}$

:

For any

![]() $j \in \lbrace {1,\ldots ,N-1\rbrace }$

, we get

$j \in \lbrace {1,\ldots ,N-1\rbrace }$

, we get

because

![]() ${\textbf{E}} \textbf{q}_j = {\textbf{e}} {\textbf{e}}^\dagger \textbf{q}_j = 0$

for any

${\textbf{E}} \textbf{q}_j = {\textbf{e}} {\textbf{e}}^\dagger \textbf{q}_j = 0$

for any

![]() $1 \leq j \leq N-1$

due to orthogonality of

$1 \leq j \leq N-1$

due to orthogonality of

![]() $\textbf{q}_j$

to

$\textbf{q}_j$

to

![]() $\textbf{q}_N = {\textbf{e}}/\sqrt {N}$

. As a consequence, each

$\textbf{q}_N = {\textbf{e}}/\sqrt {N}$

. As a consequence, each

![]() $\textbf{q}_j$

with

$\textbf{q}_j$

with

![]() $j\in \lbrace {1,\ldots ,N-1\rbrace }$

is also the eigenvector of

$j\in \lbrace {1,\ldots ,N-1\rbrace }$

is also the eigenvector of

![]() ${\textbf{M}}_0$

, associated to the eigenvalue

${\textbf{M}}_0$

, associated to the eigenvalue

![]() $1 + \nu \kappa _j$

. In addition, we have

$1 + \nu \kappa _j$

. In addition, we have

since

![]() ${\textbf{E}} \textbf{q}_N /N = \textbf{q}_N$

. Therefore,

${\textbf{E}} \textbf{q}_N /N = \textbf{q}_N$

. Therefore,

![]() $\textbf{q}_N$

is the eigenvector of

$\textbf{q}_N$

is the eigenvector of

![]() ${\textbf{M}}_0$

associated with the eigenvalue

${\textbf{M}}_0$

associated with the eigenvalue

![]() $1$

. We use this spectral information to invert the matrix

$1$

. We use this spectral information to invert the matrix

![]() ${\textbf{M}}_0$

as

${\textbf{M}}_0$

as

\begin{equation} {\textbf{M}}_0^{-1} = \textbf{q}_N \textbf{q}_N^\dagger + \sum \limits _{j=1}^{N-1} \textbf{q}_j (1 + \nu \kappa _j)^{-1} \textbf{q}_j^\dagger . \end{equation}

\begin{equation} {\textbf{M}}_0^{-1} = \textbf{q}_N \textbf{q}_N^\dagger + \sum \limits _{j=1}^{N-1} \textbf{q}_j (1 + \nu \kappa _j)^{-1} \textbf{q}_j^\dagger . \end{equation}

Substituting this spectral representation into Eq. (2.21), we get

\begin{equation} {\textbf{A}} = - \nu \sum \limits _{j=1}^{N-1} \textbf{q}_j (1 + \nu \kappa _j)^{-1} \textbf{q}_j^\dagger {\textbf{e}}_k, \end{equation}

\begin{equation} {\textbf{A}} = - \nu \sum \limits _{j=1}^{N-1} \textbf{q}_j (1 + \nu \kappa _j)^{-1} \textbf{q}_j^\dagger {\textbf{e}}_k, \end{equation}

where we used the orthogonality of the eigenvectors

![]() $\textbf{q}_j$

. Substitution of this expression into Eq. (2.17) yields

$\textbf{q}_j$

. Substitution of this expression into Eq. (2.17) yields

![]() $\chi _k = 1/N$

. This is consistent with the interpretation of

$\chi _k = 1/N$

. This is consistent with the interpretation of

![]() $\chi _k$

as the volume-averaged splitting probability: when all patches are identical and equally spaced on the boundary of the unit disk, they are equivalent from the uniformly distributed starting point, so that

$\chi _k$

as the volume-averaged splitting probability: when all patches are identical and equally spaced on the boundary of the unit disk, they are equivalent from the uniformly distributed starting point, so that

![]() $\overline {S}_k = 1/N$

from Eq. (2.22).

$\overline {S}_k = 1/N$

from Eq. (2.22).

To complete this example, we will simplify Eq. (2.33) by using the explicit form (2.28) of the surface Neumann Green’s function for the unit disk. Since the centres of the patches

![]() ${{\boldsymbol{x}}}_j$

are equally spaced on the domain boundary, we have

${{\boldsymbol{x}}}_j$

are equally spaced on the domain boundary, we have

![]() ${{\boldsymbol{x}}}_j = e^{2\pi i(\,j-1)/N} = \omega ^{\,j-1}$

for

${{\boldsymbol{x}}}_j = e^{2\pi i(\,j-1)/N} = \omega ^{\,j-1}$

for

![]() $j\in \lbrace {1,\ldots ,N\rbrace }$

. In this way, substituting Eq. (2.28) into Eq. (2.33), we get

$j\in \lbrace {1,\ldots ,N\rbrace }$

. In this way, substituting Eq. (2.28) into Eq. (2.33), we get

where we interpret points as complex numbers and

![]() $|z|$

as the modulus of

$|z|$

as the modulus of

![]() $z$

. For

$z$

. For

![]() $j=N$

, for which

$j=N$

, for which

![]() $\omega ^{Nm}=1$

, we get

$\omega ^{Nm}=1$

, we get

\begin{equation} \kappa _N = \frac {N}{8} - \ln \left \vert \prod _{m=1}^{N-1}(1-\omega ^m)\right \vert = \frac {N}{8}-\ln {N} , \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \kappa _N = \frac {N}{8} - \ln \left \vert \prod _{m=1}^{N-1}(1-\omega ^m)\right \vert = \frac {N}{8}-\ln {N} , \end{equation}

where the product in Eq. (2.39) was evaluated by using the roots of unity together with L’Hopital’s rule to get

![]() $\lim _{z\to 1} {(z^N-1)/(z-1)}=N=\prod _{m=1}^{N-1}(1-\omega ^m)$

. For

$\lim _{z\to 1} {(z^N-1)/(z-1)}=N=\prod _{m=1}^{N-1}(1-\omega ^m)$

. For

![]() $j\lt N$

, the first term in Eq. (2.38) vanishes and we obtain

$j\lt N$

, the first term in Eq. (2.38) vanishes and we obtain

which reduces after some simplifications to

for

![]() $j\in \lbrace {1,\ldots ,N-1\rbrace }$

. The asymptotic behaviour of

$j\in \lbrace {1,\ldots ,N-1\rbrace }$

. The asymptotic behaviour of

![]() $\kappa _j$

for large

$\kappa _j$

for large

![]() $N$

is derived in Appendix B.

$N$

is derived in Appendix B.

3. Splitting probability on Robin patches

In most applications, targets are not perfectly reactive [Reference Bressloff6, Reference Collins and Kimball19, Reference Erban and Chapman24, Reference Galanti, Fanelli and Piazza27, Reference Grebenkov31, Reference Grebenkov32, Reference Grebenkov35, Reference Lawley and Keener55, Reference Piazza64, Reference Sano and Tachiya71, Reference Sapoval72]. Starting from Collins and Kimball [Reference Collins and Kimball19], partial reactivity is usually implemented by replacing a Dirichlet boundary condition by a Robin condition. In the case of splitting probabilities, a straightforward generalisation of the previous setting consists in replacing Dirichlet boundary condition (2.1b) by the Robin boundary condition:

where the constant

![]() $0 \lt q_j \lt \infty$

characterises the reactivity of the

$0 \lt q_j \lt \infty$

characterises the reactivity of the

![]() $j$

-th patch

$j$

-th patch

![]() $\Gamma _{\varepsilon _j}$

. Here, we excluded the limit

$\Gamma _{\varepsilon _j}$

. Here, we excluded the limit

![]() $q_j = 0$

that would correspond to an inert patch that could be treated as a part of the reflecting boundary

$q_j = 0$

that would correspond to an inert patch that could be treated as a part of the reflecting boundary

![]() $\partial \Omega _0$

. The Dirichlet condition is recovered in the limit

$\partial \Omega _0$

. The Dirichlet condition is recovered in the limit

![]() $q_j \to +\infty$

.

$q_j \to +\infty$

.

The change of the boundary condition on the patch is a local effect that does not impact the outer solution. In turn, the inner solution near each patch

![]() $\Gamma _{\varepsilon _j}$

in Eq. (2.2) should now be replaced by

$\Gamma _{\varepsilon _j}$

in Eq. (2.2) should now be replaced by

where

![]() $g_{\mu }(\,{\boldsymbol{y}})$

is the Robin Green’s function, which satisfies

$g_{\mu }(\,{\boldsymbol{y}})$

is the Robin Green’s function, which satisfies

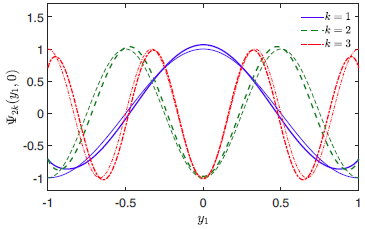

In Appendix C, we derive a spectral expansion for this Green’s function:

for any

![]() $\mu \notin \bigcup _{k=0}^\infty \{- \mu _{2k}\}$

. Here,

$\mu \notin \bigcup _{k=0}^\infty \{- \mu _{2k}\}$

. Here,

![]() $\mu _k$

and

$\mu _k$

and

![]() $\Psi _k(\,{\boldsymbol{y}})$

are the eigenvalues and eigenfunctions of the auxiliary Steklov-Neumann problem in the upper-half-plane:

$\Psi _k(\,{\boldsymbol{y}})$

are the eigenvalues and eigenfunctions of the auxiliary Steklov-Neumann problem in the upper-half-plane:

An efficient numerical procedure for computing these eigenmodes is summarised in Appendix D. Once tabulated, these eigenfunctions play a role of ‘special functions’, like orthogonal polynomials.

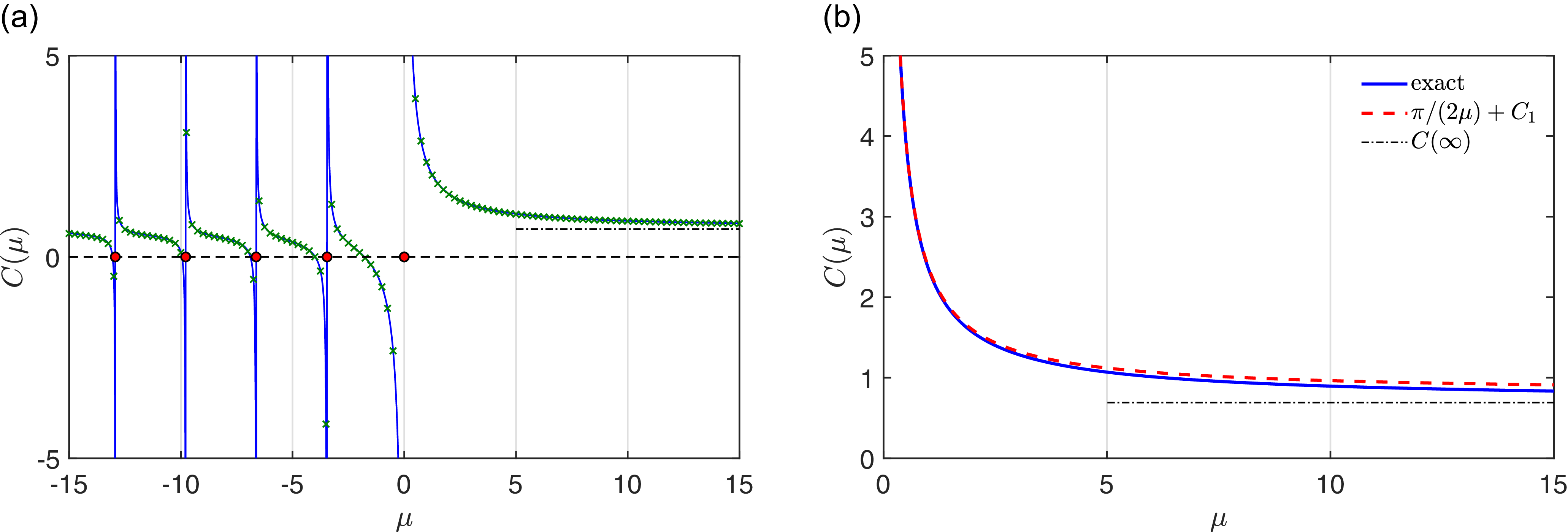

Figure 3.

(a) Function

![]() ${\mathcal{C}}(\mu )$

from Eq. (3.7), in which the infinite series is truncated either to 50 terms (solid line) or to 10 terms (crosses), to highlight the accuracy of both truncations. Filled circles indicate the values

${\mathcal{C}}(\mu )$

from Eq. (3.7), in which the infinite series is truncated either to 50 terms (solid line) or to 10 terms (crosses), to highlight the accuracy of both truncations. Filled circles indicate the values

![]() $-\mu _{2k}$

, at which

$-\mu _{2k}$

, at which

![]() ${\mathcal{C}}(\mu )$

diverges. Dash-dotted line outlines the asymptotic limit

${\mathcal{C}}(\mu )$

diverges. Dash-dotted line outlines the asymptotic limit

![]() $\ln (2)$

of

$\ln (2)$

of

![]() ${\mathcal{C}}(\mu )$

as

${\mathcal{C}}(\mu )$

as

![]() $\mu \to \infty$

. (b) Comparison of

$\mu \to \infty$

. (b) Comparison of

![]() ${\mathcal{C}}(\mu )$

and its approximation (3.10), which is accurate over a broad range of

${\mathcal{C}}(\mu )$

and its approximation (3.10), which is accurate over a broad range of

![]() $\mu$

.

$\mu$

.

As a consequence, Eq. (3.4) determines the constant term

![]() ${\mathcal{C}}(\mu )$

in the asymptotic behaviour of

${\mathcal{C}}(\mu )$

in the asymptotic behaviour of

![]() $g_\mu (\,{\boldsymbol{y}})$

at infinity, defined by

$g_\mu (\,{\boldsymbol{y}})$

at infinity, defined by

In the limit

![]() $|{\boldsymbol{y}}| \to \infty$

, we get

$|{\boldsymbol{y}}| \to \infty$

, we get

for any

![]() $\mu \notin \bigcup _{k=0}^\infty \{- \mu _{2k}\}$

, where we used

$\mu \notin \bigcup _{k=0}^\infty \{- \mu _{2k}\}$

, where we used

![]() $\mu _0 = 0$

and

$\mu _0 = 0$

and

![]() $\Psi _0(\infty ) = 1/\sqrt {2}$

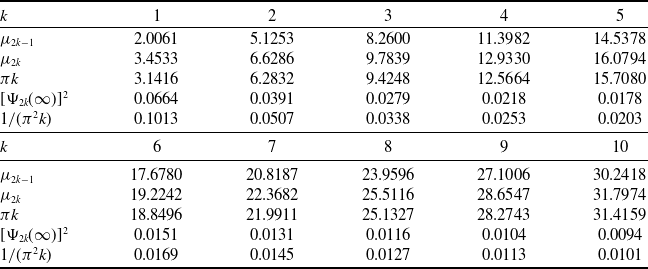

(see Appendix C for more details). The first ten coefficients contributing to

$\Psi _0(\infty ) = 1/\sqrt {2}$

(see Appendix C for more details). The first ten coefficients contributing to

![]() ${\mathcal{C}}(\mu )$

are listed in Table C1, while Figure 3 illustrates the behaviour of the function

${\mathcal{C}}(\mu )$

are listed in Table C1, while Figure 3 illustrates the behaviour of the function

![]() ${\mathcal{C}}(\mu )$

.

${\mathcal{C}}(\mu )$

.

A Taylor expansion of Eq. (3.7) near

![]() $\mu =0$

yields

$\mu =0$

yields

where the coefficients

![]() $C_n$

can be expressed in terms of

$C_n$

can be expressed in terms of

![]() $\mu _{2k}$

and

$\mu _{2k}$

and

![]() $\Psi _{2k}(\infty )$

(see Appendix C). Moreover, we calculated in Appendix E the exact values of the first two coefficients as

$\Psi _{2k}(\infty )$

(see Appendix C). Moreover, we calculated in Appendix E the exact values of the first two coefficients as

Since the second and higher-order coefficients turn out to be small, the following small-

![]() $\mu$

approximation,

$\mu$

approximation,

is remarkably accurate as seen in both Figure 3(b) and Figure 4. This approximation is one of the key results needed for Sections 4 and 5 below.

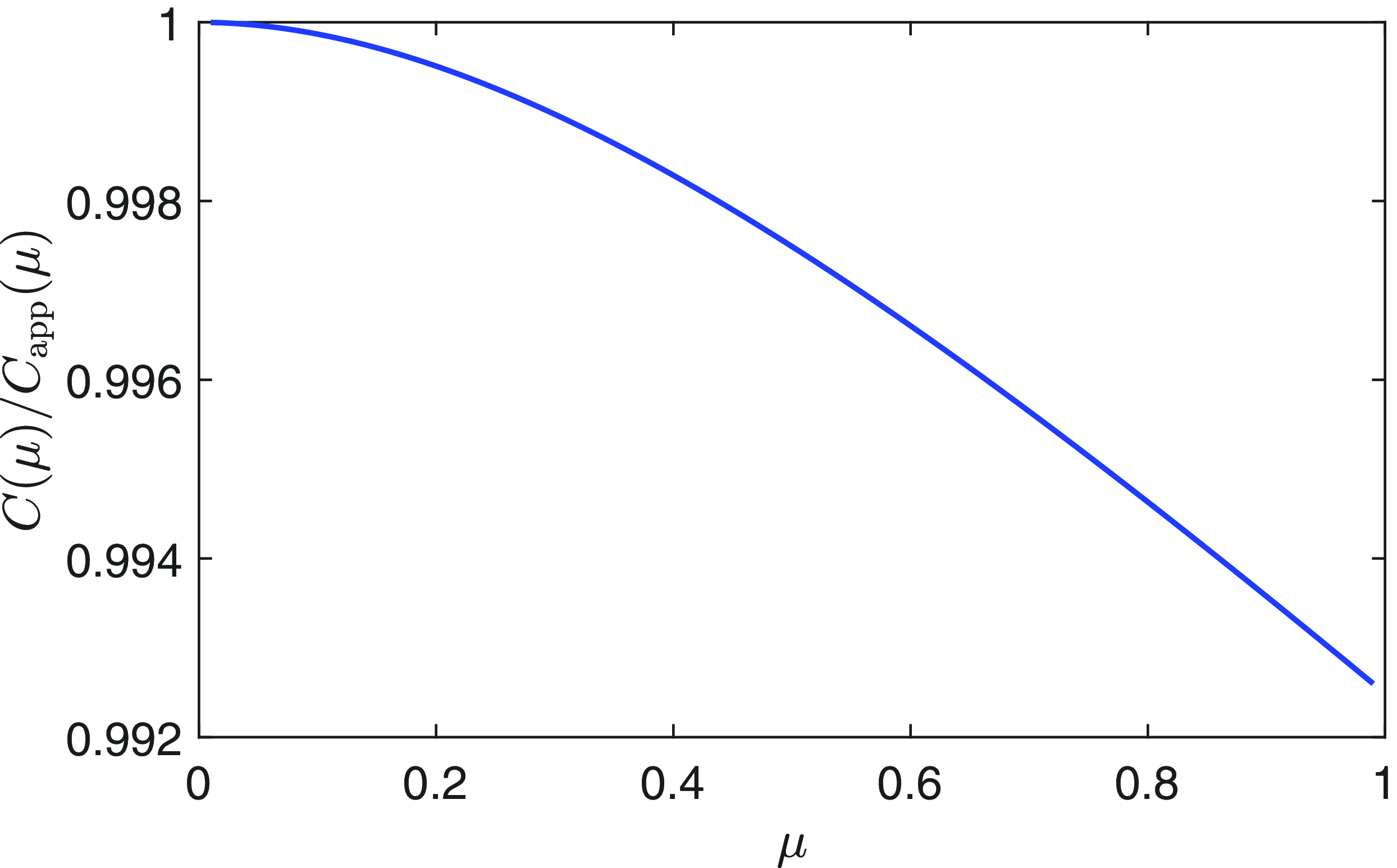

Figure 4. The ratio of

![]() ${\mathcal{C}}(\mu )$

with its approximation (3.10) is very close to unity on the range

${\mathcal{C}}(\mu )$

with its approximation (3.10) is very close to unity on the range

![]() $0\lt \mu \lt 1$

.

$0\lt \mu \lt 1$

.

The relation (3.6) implies

where we now redefine

![]() $\nu _j$

as

$\nu _j$

as

It follows that the far-field behaviour of the inner solution is identical to that in Eq. (2.7) for Dirichlet patches, whereas the partial reactivity is fully taken into account through the new definition (3.12) of

![]() $\nu _j$

. As a consequence, we retrieve the same representation (2.12) for the splitting probability

$\nu _j$

. As a consequence, we retrieve the same representation (2.12) for the splitting probability

![]() $S_k({{\boldsymbol{x}}})$

, with the coefficients

$S_k({{\boldsymbol{x}}})$

, with the coefficients

![]() $A_i$

and

$A_i$

and

![]() $\chi _k$

given by Eqs. (2.17, 2.21). This equivalence shows that partially reactive targets with

$\chi _k$

given by Eqs. (2.17, 2.21). This equivalence shows that partially reactive targets with

![]() $q_j \gt 0$

can still be treated as the perfect ones but with the reduced effective length, defined by

$q_j \gt 0$

can still be treated as the perfect ones but with the reduced effective length, defined by

Together with the spectral expansion (3.7), this is the main result of this section.

From Eq. (3.7), the function

![]() ${\mathcal{C}}(\mu )$

decreases monotonically from

${\mathcal{C}}(\mu )$

decreases monotonically from

![]() $+\infty$

to

$+\infty$

to

![]() $\ln (2)$

on the range

$\ln (2)$

on the range

![]() $\mu \gt 0$

(see Figure 3). As a consequence,

$\mu \gt 0$

(see Figure 3). As a consequence,

![]() $\nu _j$

in Eq. (3.12) decreases monotonically from

$\nu _j$

in Eq. (3.12) decreases monotonically from

![]() $-1/\ln (\varepsilon _j/2)$

(this is the former definition of

$-1/\ln (\varepsilon _j/2)$

(this is the former definition of

![]() $\nu _j$

for the Dirichlet patch) to

$\nu _j$

for the Dirichlet patch) to

![]() $0$

, whereas

$0$

, whereas

![]() $\varepsilon _j^{\textrm {eff}}$

decreases from

$\varepsilon _j^{\textrm {eff}}$

decreases from

![]() $\varepsilon _j$

to

$\varepsilon _j$

to

![]() $0$

as the reactivity

$0$

as the reactivity

![]() $q_j$

drops from infinity to

$q_j$

drops from infinity to

![]() $0$

. This shows that a target with a smaller reactivity has less chance to capture the diffusing particle. When

$0$

. This shows that a target with a smaller reactivity has less chance to capture the diffusing particle. When

![]() $q_j \sim {\mathcal O}(1)$

, one has

$q_j \sim {\mathcal O}(1)$

, one has

![]() $\varepsilon _j q_j \ll 1$

, so that the approximation (3.10) is applicable. This yields, that

$\varepsilon _j q_j \ll 1$

, so that the approximation (3.10) is applicable. This yields, that

![]() $\nu _j \approx 2\varepsilon _j q_j/\pi \ll 1$

and so to leading order

$\nu _j \approx 2\varepsilon _j q_j/\pi \ll 1$

and so to leading order

For weakly reactive targets (i.e., if

![]() $q_j \varepsilon _j \ll 1$

for all

$q_j \varepsilon _j \ll 1$

for all

![]() $j = 1,\ldots ,N$

), we get

$j = 1,\ldots ,N$

), we get

![]() $\nu _j \approx 2\varepsilon _j q_j/\pi \ll 1$

. According to Eq. (2.21), all the coefficients

$\nu _j \approx 2\varepsilon _j q_j/\pi \ll 1$

. According to Eq. (2.21), all the coefficients

![]() $A_i$

are small (of the order of

$A_i$

are small (of the order of

![]() $\varepsilon$

) so that the first term in Eq. (2.17) can be neglected, yielding

$\varepsilon$

) so that the first term in Eq. (2.17) can be neglected, yielding

and thus

independently of the location of the patches. We emphasise that the approximation (3.15) is generally not accurate for perfect targets: even if

![]() $\varepsilon _j$

are very small, the gauge function

$\varepsilon _j$

are very small, the gauge function

![]() $\nu _j = -1/\ln (\varepsilon _j/2)$

may not be small enough to neglect higher-order terms in powers of

$\nu _j = -1/\ln (\varepsilon _j/2)$

may not be small enough to neglect higher-order terms in powers of

![]() $\nu _j$

.

$\nu _j$

.

For the case of two partially reactive patches on the boundary of the unit disk, substitution of the effective lengths

![]() $\varepsilon _j^{\textrm {eff}}$

from Eq. (3.13) into Eq. (2.29) yields

$\varepsilon _j^{\textrm {eff}}$

from Eq. (3.13) into Eq. (2.29) yields

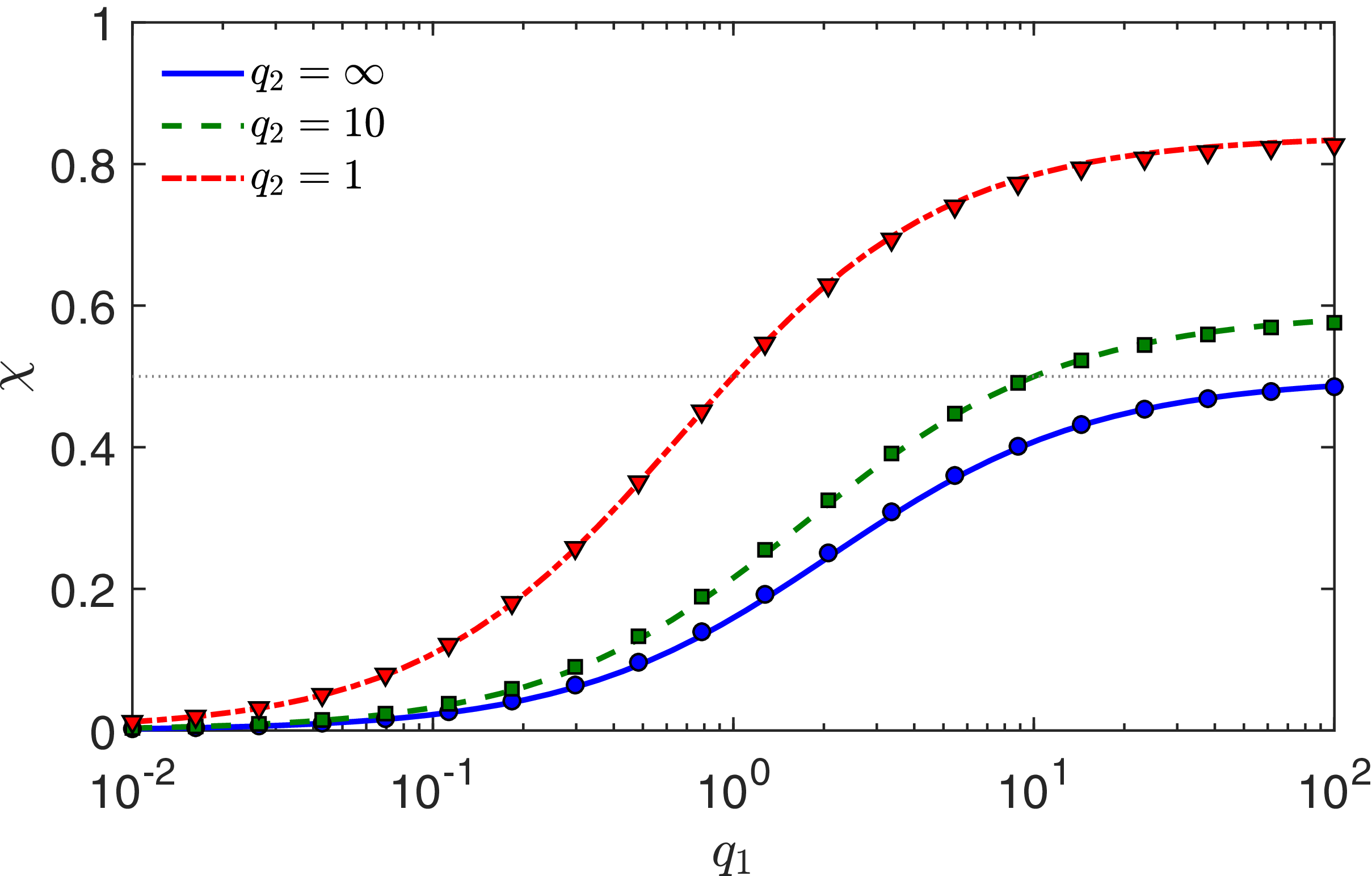

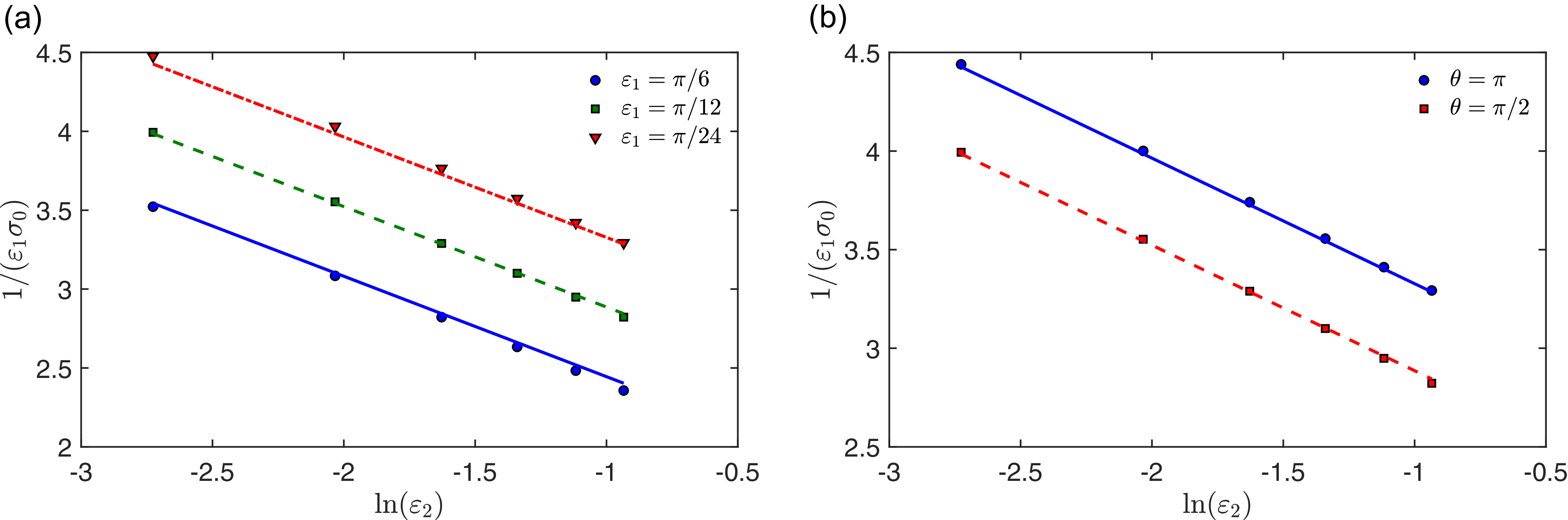

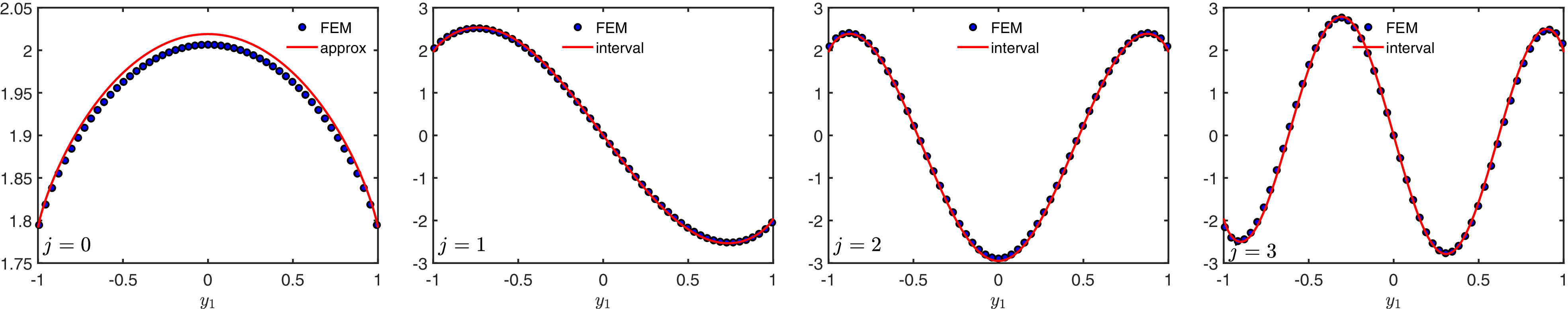

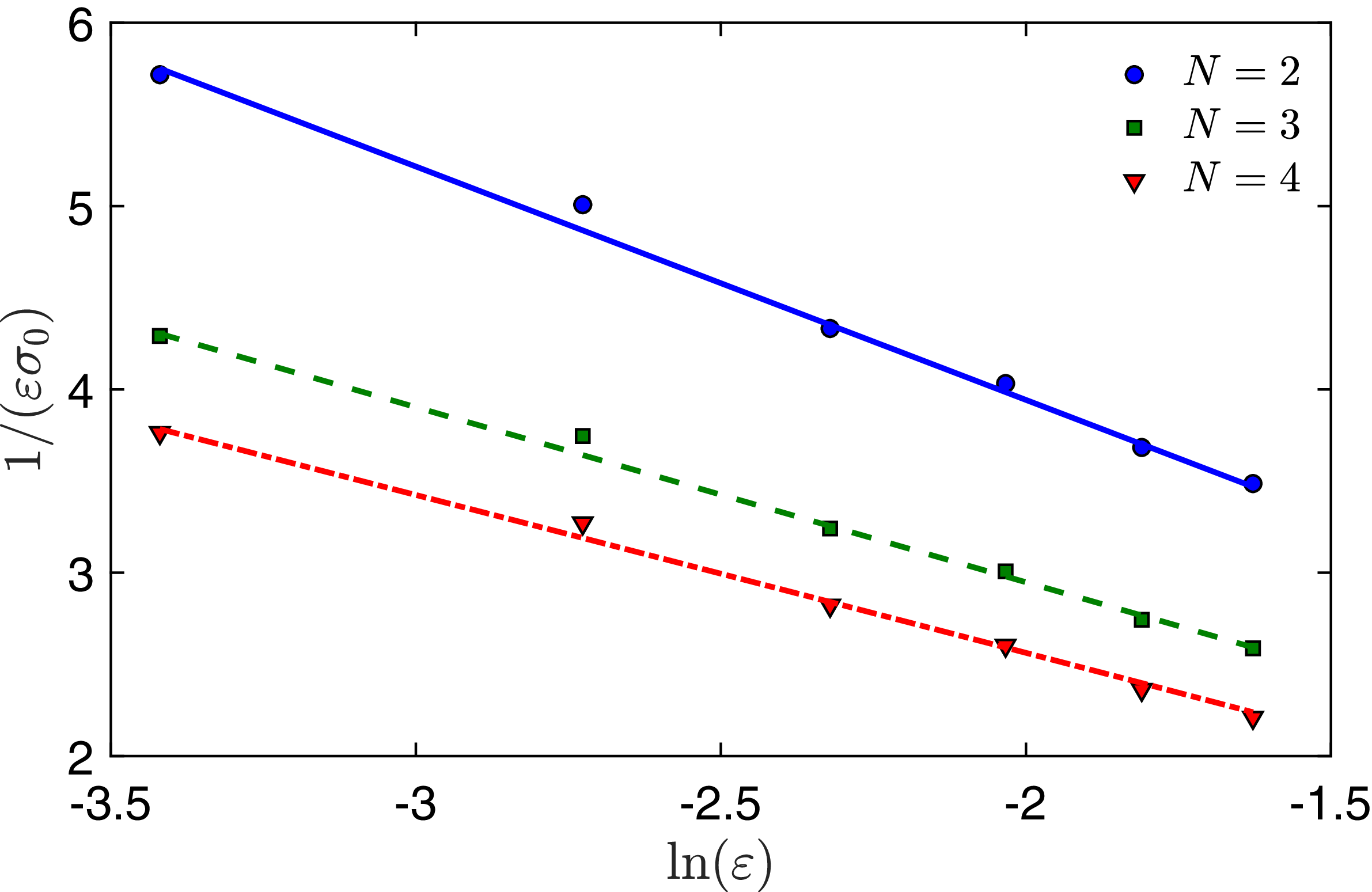

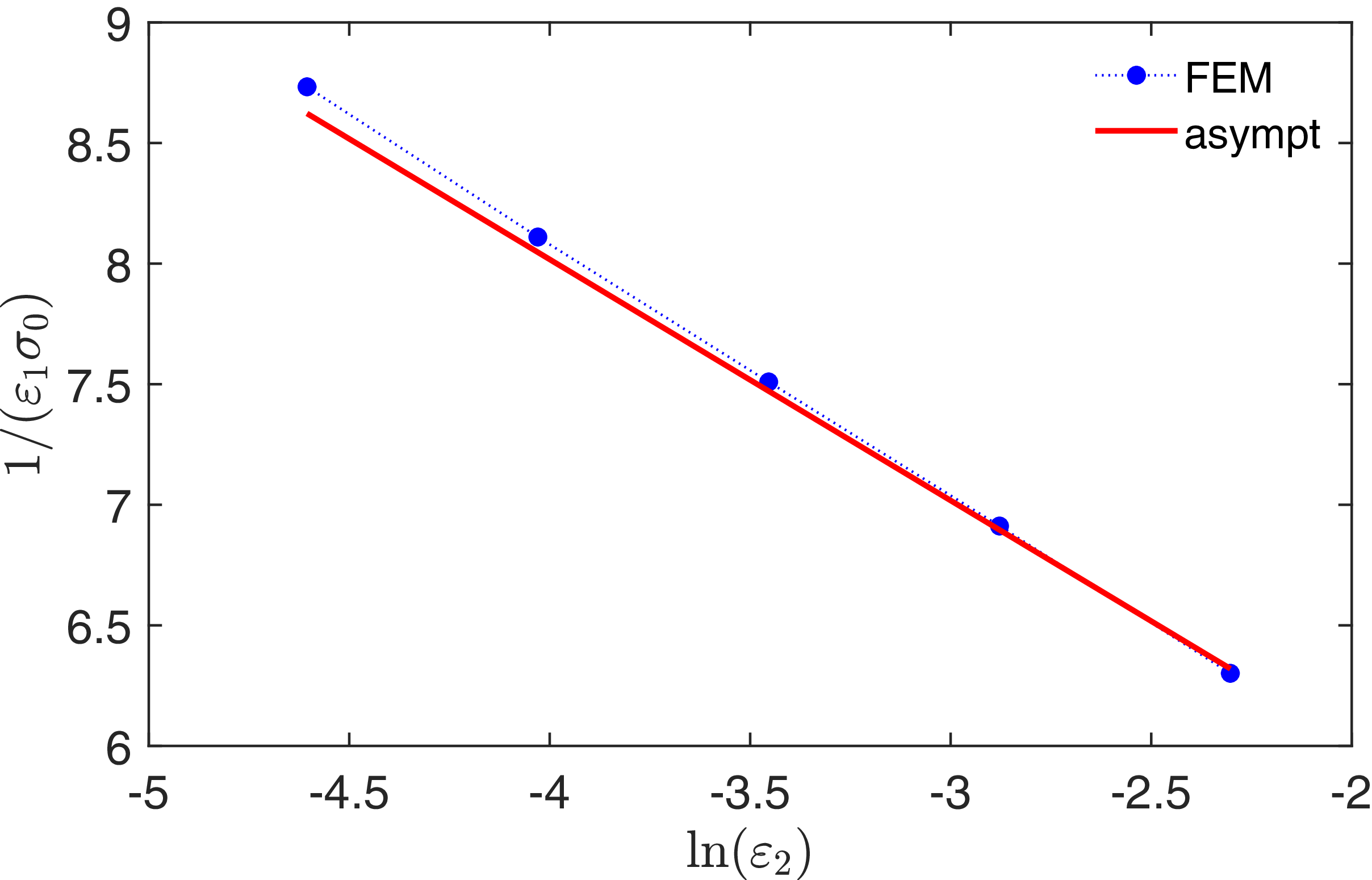

Figure 5 shows the behaviour of

![]() $\chi _1$

for two patches of equal length. In this figure, the high accuracy of our asymptotic solution (3.17b) is confirmed by comparison with a numerical solution of the BVP (2.1b) with Robin boundary condition (3.1) by a finite-element method.

$\chi _1$

for two patches of equal length. In this figure, the high accuracy of our asymptotic solution (3.17b) is confirmed by comparison with a numerical solution of the BVP (2.1b) with Robin boundary condition (3.1) by a finite-element method.

Figure 5. Volume-averaged splitting probability

![]() $\overline {S}_1 = \chi _1$

for the unit disk, calculated from (3.17b), with two patches of equal length

$\overline {S}_1 = \chi _1$

for the unit disk, calculated from (3.17b), with two patches of equal length

![]() $2\varepsilon = 0.2$

located at boundary points

$2\varepsilon = 0.2$

located at boundary points

![]() $({\pm} 1,0)$

. Three curves correspond to three values of the reactivity parameter

$({\pm} 1,0)$

. Three curves correspond to three values of the reactivity parameter

![]() $q_2$

of the second patch. Symbols present the numerical solution of the BVP (2.1b) with Robin boundary condition (3.1) by a finite-element method in Matlab PDEtool, with the maximal mesh size

$q_2$

of the second patch. Symbols present the numerical solution of the BVP (2.1b) with Robin boundary condition (3.1) by a finite-element method in Matlab PDEtool, with the maximal mesh size

![]() $0.02$

.

$0.02$

.

3.1. The mean first-reaction time

Although our asymptotic analysis has focused on calculating splitting probabilities it can be easily modified to calculate the mean first-reaction time (MFRT).

The dimensionless MFRT

![]() $u({{\boldsymbol{x}}})$

satisfies a Poisson equation with mixed Neumann-Robin boundary conditions:

$u({{\boldsymbol{x}}})$

satisfies a Poisson equation with mixed Neumann-Robin boundary conditions:

As previously, each reactive boundary patch

![]() $\Gamma _{\varepsilon _i}$

has length

$\Gamma _{\varepsilon _i}$

has length

![]() $2\varepsilon _i$

, reactivity parameter

$2\varepsilon _i$

, reactivity parameter

![]() $q_i$

, and is centred at

$q_i$

, and is centred at

![]() ${{\boldsymbol{x}}}_i\in \partial \Omega$

.

${{\boldsymbol{x}}}_i\in \partial \Omega$

.

The matched asymptotic analysis of Eq. (3.18) in the small-target limit

![]() $\varepsilon _i\ll 1$

is very similar to that for analysing the splitting probability. The inner solution near the

$\varepsilon _i\ll 1$

is very similar to that for analysing the splitting probability. The inner solution near the

![]() $j$

-th patch in terms of an unknown coefficient

$j$

-th patch in terms of an unknown coefficient

![]() $A_j$

is

$A_j$

is

where

![]() $\mu _j\equiv \varepsilon _j q_j$

and

$\mu _j\equiv \varepsilon _j q_j$

and

![]() $g_{\mu }(\,{\boldsymbol{y}})$

is the Robin Green’s satisfying Eq. (3.3) with far-field behaviour Eq. (3.6). Upon matching the far-field behaviour of

$g_{\mu }(\,{\boldsymbol{y}})$

is the Robin Green’s satisfying Eq. (3.3) with far-field behaviour Eq. (3.6). Upon matching the far-field behaviour of

![]() $V_{j}(\,{\boldsymbol{y}})$

to the outer solution, we find that to within all logarithmic terms the outer solution satisfies

$V_{j}(\,{\boldsymbol{y}})$

to the outer solution, we find that to within all logarithmic terms the outer solution satisfies

where

![]() $\nu _j$

is defined by (3.12). The solvability condition for (3.20) is that

$\nu _j$

is defined by (3.12). The solvability condition for (3.20) is that

![]() $\sum _{j=1}^{N} A_j={|\Omega |/\pi }$

. We then represent

$\sum _{j=1}^{N} A_j={|\Omega |/\pi }$

. We then represent

![]() $u$

in terms of the surface Neumann Green’s function and the volume average

$u$

in terms of the surface Neumann Green’s function and the volume average

![]() $\overline {u}_0=|\Omega |^{-1}\int _{\Omega } u({{\boldsymbol{x}}})\, d{{\boldsymbol{x}}}$

as

$\overline {u}_0=|\Omega |^{-1}\int _{\Omega } u({{\boldsymbol{x}}})\, d{{\boldsymbol{x}}}$

as

Imposing the singularity behaviour in Eq. (3.20b), we obtain an

![]() $(N+1)$

-dimensional linear algebraic system for

$(N+1)$

-dimensional linear algebraic system for

![]() $\overline {u}_0$

and

$\overline {u}_0$

and

![]() $A_1,\ldots ,A_N$

given by

$A_1,\ldots ,A_N$

given by

\begin{equation} A_j + \nu _j\left[A_j R_j + \sum \limits _{i=1 \atop i\ne j}^N G_{j,i} A_i\right] = \overline {u}_0 \nu _j, \quad j\in \lbrace {1,\ldots ,N\rbrace }; \qquad \sum _{j=1}^{N} A_j = \frac {|\Omega |}{\pi } , \end{equation}

\begin{equation} A_j + \nu _j\left[A_j R_j + \sum \limits _{i=1 \atop i\ne j}^N G_{j,i} A_i\right] = \overline {u}_0 \nu _j, \quad j\in \lbrace {1,\ldots ,N\rbrace }; \qquad \sum _{j=1}^{N} A_j = \frac {|\Omega |}{\pi } , \end{equation}

where

![]() $G_{j,i}$

and

$G_{j,i}$

and

![]() $R_i$

were defined in (2.14). In matrix form Eq. (3.22) is written for

$R_i$

were defined in (2.14). In matrix form Eq. (3.22) is written for

![]() ${\textbf{A}}\equiv (A_1,\ldots ,A_N)^\dagger$

as

${\textbf{A}}\equiv (A_1,\ldots ,A_N)^\dagger$

as

where

![]() $\textbf{e}$

,

$\textbf{e}$

,

![]() $\boldsymbol \nu$

and the Green’s matrix

$\boldsymbol \nu$

and the Green’s matrix

![]() $\textbf{G}$

were defined in Eq. (2.15). By eliminating

$\textbf{G}$

were defined in Eq. (2.15). By eliminating

![]() $\overline {u}_0$

in Eq. (3.23), we conclude that

$\overline {u}_0$

in Eq. (3.23), we conclude that

where

![]() $\bar {\nu }\equiv \sum \limits _{j=1}^N \nu _j$

, while

$\bar {\nu }\equiv \sum \limits _{j=1}^N \nu _j$

, while

![]() $\textbf{A}$

is the solution to

$\textbf{A}$

is the solution to

with

![]() ${\textbf{M}}_0$

and

${\textbf{M}}_0$

and

![]() $\textbf{E}$

being defined in Eq. (2.20).

$\textbf{E}$

being defined in Eq. (2.20).

By using Eq. (3.12) for

![]() $\nu _j$

, which involves the local reactivity parameter

$\nu _j$

, which involves the local reactivity parameter

![]() $q_j$

on the patch, one can invert

$q_j$

on the patch, one can invert

![]() ${\textbf{M}}_0$

in Eq. (3.25) to get the coefficients

${\textbf{M}}_0$

in Eq. (3.25) to get the coefficients

![]() $A_j$

. As a consequence, Eq. (3.24) gives access to the volume-averaged MFRT

$A_j$

. As a consequence, Eq. (3.24) gives access to the volume-averaged MFRT

![]() $\overline {u}_0$

, whereas Eq. (3.21) determines the MFRT

$\overline {u}_0$

, whereas Eq. (3.21) determines the MFRT

![]() $u({{\boldsymbol{x}}})$

for any well-separated spatial configuration of partially reactive patches. This result generalises that in [Reference Pillay, Ward, Peirce and Kolokolnikov65], where perfect reactivities (

$u({{\boldsymbol{x}}})$

for any well-separated spatial configuration of partially reactive patches. This result generalises that in [Reference Pillay, Ward, Peirce and Kolokolnikov65], where perfect reactivities (

![]() $q_j=\infty$

) were assumed.

$q_j=\infty$

) were assumed.

4. Steklov-Neumann problem

As discussed in Section 1, the Robin boundary condition describes targets with a constant reactivity. In turn, more sophisticated surface reactions can be incorporated by using the encounter-based approach [Reference Grebenkov33, Reference Grebenkov34, Reference Grebenkov36], which relies on the mixed Steklov-Neumann problem. In this section, we apply the tools described above to derive the asymptotic properties of this spectral problem in the small-target limit.

As before, we consider a bounded planar domain

![]() $\Omega$

with a smooth boundary

$\Omega$

with a smooth boundary

![]() $\partial \Omega$

, which has

$\partial \Omega$

, which has

![]() $N$

small well-separated patches

$N$

small well-separated patches

![]() $\Gamma _{\varepsilon _j}$

, and

$\Gamma _{\varepsilon _j}$

, and

![]() $\partial \Omega _0 = \partial \Omega \backslash (\Gamma _{\varepsilon _1} \cup \ldots \cup \Gamma _{\varepsilon _N})$

. We study the mixed Steklov-Neumann spectral problem:

$\partial \Omega _0 = \partial \Omega \backslash (\Gamma _{\varepsilon _1} \cup \ldots \cup \Gamma _{\varepsilon _N})$

. We study the mixed Steklov-Neumann spectral problem:

This spectral problem is known to have a discrete positive spectrum [Reference Levitin, Mangoubi and Polterovich56], i.e., infinitely many eigenpairs

![]() $\{\sigma _k, V_k\}$

that are enumerated by

$\{\sigma _k, V_k\}$

that are enumerated by

![]() $k = 0,1,\ldots$

to form an increasing sequence of eigenvalues:

$k = 0,1,\ldots$

to form an increasing sequence of eigenvalues:

![]() $0 = \sigma _0 \lt \sigma _1 \leq \sigma _2 \leq \ldots \nearrow \infty$

. Note that the Steklov boundary condition (4.1b) with a nonnegative

$0 = \sigma _0 \lt \sigma _1 \leq \sigma _2 \leq \ldots \nearrow \infty$

. Note that the Steklov boundary condition (4.1b) with a nonnegative

![]() $\sigma$

differs from the previous Robin condition by the opposite sign. We aim at determining the asymptotic behaviour of the eigenvalues

$\sigma$

differs from the previous Robin condition by the opposite sign. We aim at determining the asymptotic behaviour of the eigenvalues

![]() $\sigma _k$

and the associated eigenfunctions

$\sigma _k$

and the associated eigenfunctions

![]() $V_k$

in the small-target limit.

$V_k$

in the small-target limit.

In the case of a single Steklov patch (

![]() $N = 1$

), the small-

$N = 1$

), the small-

![]() $\varepsilon _1$

asymptotic behaviour of the eigenvalues and eigenfunctions was analysed in [Reference Grebenkov38]. In fact, a simple scaling argument suggests that

$\varepsilon _1$

asymptotic behaviour of the eigenvalues and eigenfunctions was analysed in [Reference Grebenkov38]. In fact, a simple scaling argument suggests that

![]() $\sigma _j \approx \mu _j/\varepsilon _1$

(

$\sigma _j \approx \mu _j/\varepsilon _1$

(

![]() $j=1,2,\ldots$

) to leading order, where

$j=1,2,\ldots$

) to leading order, where

![]() $\mu _j$

are the eigenvalues of the mixed Steklov-Neumann problem (3.5) for the interval in the upper-half-plane (see also Appendix C).

$\mu _j$

are the eigenvalues of the mixed Steklov-Neumann problem (3.5) for the interval in the upper-half-plane (see also Appendix C).

If there are two well-separated Steklov patches, it is tempting to apply the same scaling argument in the vicinity of each patch. In this way, we can expect that the spectrum of the problem (4.1) with

![]() $N = 2$

is composed of two sequences of eigenvalues:

$N = 2$

is composed of two sequences of eigenvalues:

![]() $\{\mu _j/\varepsilon _1\}$

from the first patch of length

$\{\mu _j/\varepsilon _1\}$

from the first patch of length

![]() $2\varepsilon _1$

, and

$2\varepsilon _1$

, and

![]() $\{\mu _j/\varepsilon _2\}$

from the second patch of length

$\{\mu _j/\varepsilon _2\}$

from the second patch of length

![]() $2\varepsilon _2$

. In other words, the two patches might be expected to not interact with each other in the small-target limit as

$2\varepsilon _2$

. In other words, the two patches might be expected to not interact with each other in the small-target limit as

![]() $\varepsilon _j \to 0$

. This intuitive argument turns out to be correct for all the eigenvalues, except for the first nontrivial eigenvalue

$\varepsilon _j \to 0$

. This intuitive argument turns out to be correct for all the eigenvalues, except for the first nontrivial eigenvalue

![]() $\sigma _1$

. Indeed, if two patches could be treated as independent, the eigenvalue

$\sigma _1$

. Indeed, if two patches could be treated as independent, the eigenvalue

![]() $\sigma _1$

would have to be zero, as

$\sigma _1$

would have to be zero, as

![]() $\sigma _0$

. However, the zero eigenvalue can only correspond to a constant eigenfunction, so that if

$\sigma _0$

. However, the zero eigenvalue can only correspond to a constant eigenfunction, so that if

![]() $\sigma _1$

was zero, one would have

$\sigma _1$

was zero, one would have

![]() $V_1 = const = V_0$

, which is impossible. We conclude that even if the patches are extremely small, the eigenvalue

$V_1 = const = V_0$

, which is impossible. We conclude that even if the patches are extremely small, the eigenvalue

![]() $\sigma _1$

must be strictly positive, and its asymptotic behaviour must result from long-range interactions between two patches.

$\sigma _1$

must be strictly positive, and its asymptotic behaviour must result from long-range interactions between two patches.

In this section, we adapt the analysis from Section 3 to the case of

![]() $N$

Steklov patches and determine the asymptotic behaviour of the first

$N$

Steklov patches and determine the asymptotic behaviour of the first

![]() $N-1$

eigenvalues

$N-1$

eigenvalues

![]() $\sigma _j$

, for

$\sigma _j$

, for

![]() $j \in \lbrace {1,\ldots ,N-1\rbrace }$

, in this setting.

$j \in \lbrace {1,\ldots ,N-1\rbrace }$

, in this setting.

4.1. Matched asymptotic analysis

As before, we look at the inner solution near each Steklov patch

![]() $\Gamma _{\varepsilon _j}$

. Upon comparing the Robin and Steklov conditions (3.1, 4.1b), we notice two differences: (i)

$\Gamma _{\varepsilon _j}$

. Upon comparing the Robin and Steklov conditions (3.1, 4.1b), we notice two differences: (i)

![]() $q_j$

is replaced by

$q_j$

is replaced by

![]() $-\sigma$

, and (ii) there is no inhomogeneous term

$-\sigma$

, and (ii) there is no inhomogeneous term

![]() $q_j \delta _{j,k}$

in the right-hand side. Apart from these two points, the BVPs for

$q_j \delta _{j,k}$

in the right-hand side. Apart from these two points, the BVPs for

![]() $S_k({{\boldsymbol{x}}})$

and

$S_k({{\boldsymbol{x}}})$

and

![]() $V({{\boldsymbol{x}}})$

are identical. As a consequence, we can immediately rewrite the asymptotic behaviour (3.11) for each

$V({{\boldsymbol{x}}})$

are identical. As a consequence, we can immediately rewrite the asymptotic behaviour (3.11) for each

![]() $j\in \lbrace {1,\ldots ,N\rbrace }$

as

$j\in \lbrace {1,\ldots ,N\rbrace }$

as

where we now redefine

![]() $\nu _j$

as

$\nu _j$

as

and where

![]() $A_j$

is an unknown coefficient. Note that the constant term

$A_j$

is an unknown coefficient. Note that the constant term

![]() ${\mathcal{C}}({-}\sigma \varepsilon _j)$

is not incorporated into the new definition of

${\mathcal{C}}({-}\sigma \varepsilon _j)$

is not incorporated into the new definition of

![]() $\nu _j$

, as we did earlier in the Robin case.

$\nu _j$

, as we did earlier in the Robin case.

As before, the outer solution is represented as

with an unknown constant

![]() $\chi$

. The divergence theorem still ensures the compatibility condition (2.11). Upon enforcing the singularity behaviour (4.2) for the solution in Eq. (4.4), we get

$\chi$

. The divergence theorem still ensures the compatibility condition (2.11). Upon enforcing the singularity behaviour (4.2) for the solution in Eq. (4.4), we get

where we used the matrix notations introduced in Eq. (2.15) of Section 2.3. Multiplying this equation by

![]() $\nu _j$

and introducing the diagonal matrix

$\nu _j$

and introducing the diagonal matrix

![]() $\textbf{C}$

formed by

$\textbf{C}$

formed by

![]() $\{{\mathcal{C}}({-}\sigma \varepsilon _1), \ldots , {\mathcal{C}}({-}\sigma \varepsilon _N)\}$

, we rewrite Eq. (4.5) as

$\{{\mathcal{C}}({-}\sigma \varepsilon _1), \ldots , {\mathcal{C}}({-}\sigma \varepsilon _N)\}$

, we rewrite Eq. (4.5) as

Left-multiplying this equation by

![]() ${\textbf{e}}^\dagger$

, and using

${\textbf{e}}^\dagger$

, and using

![]() ${\textbf{e}}^\dagger {\textbf{A}} = 0$

, we isolate

${\textbf{e}}^\dagger {\textbf{A}} = 0$

, we isolate

![]() $\chi$

as

$\chi$

as

where

![]() $\bar {\nu }$

was defined by Eq. (2.18). Substituting this expression back into Eq. (4.6), we obtain that

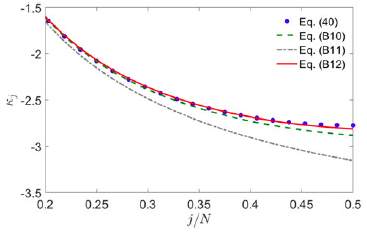

$\bar {\nu }$