1 Introduction

The Apéry numbers

$$ \begin{align*} \alpha_n = \sum_{k=0}^n{\binom nk}^2{\binom{n+k}n}^2 \quad\text{for}\; n=0,1,2,\dots, \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \alpha_n = \sum_{k=0}^n{\binom nk}^2{\binom{n+k}n}^2 \quad\text{for}\; n=0,1,2,\dots, \end{align*} $$

are a famous sequence of integer numbers, mostly known for playing a prominent role in Apéry’s proof [Reference Apéry3] of the irrationality of

![]() $\zeta (3)$

. Their generating series

$\zeta (3)$

. Their generating series ![]() enjoys many interesting properties. It is D-finite, that is, it satisfies a linear differential equation with polynomial coefficients. Starting from the differential equation, integrality of the coefficients of its solutions is highly remarkable. The Apéry numbers grow in a controlled manner, making their generating series a G-function. Moreover, letting p be an odd prime number, it is known [Reference Gessel16, Theorem 1] that the Apéry numbers have the p-Lucas property for all prime numbers p (see also the general result for Apéry-like numbers in [Reference Malik and Straub20]). That is,

enjoys many interesting properties. It is D-finite, that is, it satisfies a linear differential equation with polynomial coefficients. Starting from the differential equation, integrality of the coefficients of its solutions is highly remarkable. The Apéry numbers grow in a controlled manner, making their generating series a G-function. Moreover, letting p be an odd prime number, it is known [Reference Gessel16, Theorem 1] that the Apéry numbers have the p-Lucas property for all prime numbers p (see also the general result for Apéry-like numbers in [Reference Malik and Straub20]). That is,

![]() $\alpha _{np+\ell }\equiv \alpha _n \alpha _\ell \pmod p$

whenever

$\alpha _{np+\ell }\equiv \alpha _n \alpha _\ell \pmod p$

whenever

![]() $0 \leq \ell < p$

. On the level of generating functions, this property translates to the congruence

$0 \leq \ell < p$

. On the level of generating functions, this property translates to the congruence

![]() $f_\alpha \equiv A_p\cdot f_\alpha ^p \pmod p$

, where

$f_\alpha \equiv A_p\cdot f_\alpha ^p \pmod p$

, where ![]() denotes the truncation of

denotes the truncation of

![]() $f_\alpha $

at order p. This relation also shows that the reduction of the generating function

$f_\alpha $

at order p. This relation also shows that the reduction of the generating function

![]() $f_\alpha \bmod p$

is algebraic over the field of rational functions

$f_\alpha \bmod p$

is algebraic over the field of rational functions

![]() $\mathbb {F}_p(t)$

and that the extension it generates is Galois with cyclic Galois group of order dividing

$\mathbb {F}_p(t)$

and that the extension it generates is Galois with cyclic Galois group of order dividing

![]() $p-1$

.

$p-1$

.

Algebraicity modulo (almost) all primes p is a phenomenon observed for many classes of D-finite series. More precisely, for diagonals of multivariate rational or, equivalently, algebraic functions, this is a consequence of a theorem of Furstenberg [Reference Furstenberg15]. For hypergeometric functions, it can be deduced from work by Christol [Reference Christol9] and was made explicit by Vargas-Montoya [Reference Vargas-Montoya22]. Further, if Christol’s conjecture [Reference Christol10] proves to be true, the result of Furstenberg would apply to all globally bounded D-finite series.

Having algebraic equations for the generating function modulo prime numbers, it is natural to consider their Galois groups for each prime number p. For D-finite series whose reductions modulo infinitely many prime numbers p are algebraic, it was (conjecturally) observed in [Reference Caruso, Fürnsinn and Vargas-Montoya6] that these Galois groups show some uniformity properties across different primes and seem to be related to the differential Galois group of the minimal differential equation satisfied by the series. As an example in [Reference Caruso, Fürnsinn and Vargas-Montoya6, Section 2.1.5], the Galois groups of the reductions of the Apéry series were computed for many prime numbers using a computer algebra system. The pattern that unfolded was stated without a proof and the aim of this paper is to provide one.

Fixing a prime number p and starting from the algebraic relation given by the p-Lucas property, the Galois group of

![]() $f_\alpha \bmod p$

can canonically be seen as a subgroup of

$f_\alpha \bmod p$

can canonically be seen as a subgroup of

![]() $\mathbb {F}_p^\times $

via the embedding

$\mathbb {F}_p^\times $

via the embedding

We aim to determine the image of this map. Throughout the article, we denote by S the unique subgroup of

![]() $\mathbb {F}_p^\times $

of index

$\mathbb {F}_p^\times $

of index

![]() $2$

; it is the subgroup of squares, hence the notation.

$2$

; it is the subgroup of squares, hence the notation.

Theorem 1.1.

-

• If

$p \equiv 1, 5, 7, 11 \pmod {24}$

, then

$p \equiv 1, 5, 7, 11 \pmod {24}$

, then

$\operatorname {\mathrm {Gal}}(\mathbb {F}_p(t, f_\alpha )/\mathbb {F}_p(t)) = S$

.

$\operatorname {\mathrm {Gal}}(\mathbb {F}_p(t, f_\alpha )/\mathbb {F}_p(t)) = S$

. -

• If

$p \equiv 13, 17, 19, 23 \pmod {24}$

, then

$p \equiv 13, 17, 19, 23 \pmod {24}$

, then

$\operatorname {\mathrm {Gal}}(\mathbb {F}_p(t, f_\alpha )/\mathbb {F}_p(t)) = \mathbb {F}_p^\times $

.

$\operatorname {\mathrm {Gal}}(\mathbb {F}_p(t, f_\alpha )/\mathbb {F}_p(t)) = \mathbb {F}_p^\times $

.

This result is the Galois theoretic shadow of the following factorisation property of

![]() $A_p$

.

$A_p$

.

Theorem 1.2. There exists a polynomial

![]() $B_p \in \mathbb {F}_p[t]$

such that:

$B_p \in \mathbb {F}_p[t]$

such that:

-

• if

$p \equiv 1, 5, 7, 11 \pmod {24}$

, then

$p \equiv 1, 5, 7, 11 \pmod {24}$

, then

$A_p = B_p^2$

;

$A_p = B_p^2$

; -

• if

$p \equiv 13, 17, 19, 23 \pmod {24}$

, then

$p \equiv 13, 17, 19, 23 \pmod {24}$

, then

$A_p = (t^2 - 34t + 1) \cdot B_p^2$

.

$A_p = (t^2 - 34t + 1) \cdot B_p^2$

.

The main ingredient in our proof is the fact that the Apéry series

![]() $f_\alpha $

is related to the generating function of the Franel numbers

$f_\alpha $

is related to the generating function of the Franel numbers

by a simple rational substitution, namely

![]() $f_\alpha = (1+x)\cdot h^2$

, where the variables t and x are linked by the relation

$f_\alpha = (1+x)\cdot h^2$

, where the variables t and x are linked by the relation

![]() $t = {x(1-8x)}/{(1+x)}$

.

$t = {x(1-8x)}/{(1+x)}$

.

The sequence of Apéry numbers has two companions: the (alternating version of the) Domb numbers

$$ \begin{align*} \delta_n = (-1)^n\sum_{k=0}^n \binom{2k}k \binom{2n-2k}{n-k} {\binom nk}^2 \quad\text{for}\; n=0,1,2,\dots \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \delta_n = (-1)^n\sum_{k=0}^n \binom{2k}k \binom{2n-2k}{n-k} {\binom nk}^2 \quad\text{for}\; n=0,1,2,\dots \end{align*} $$

and the Almkvist–Zudilin numbers

$$ \begin{align*} \xi_n=\sum_{k=0}^n(-1)^{n-k}3^{n-3k}\frac{(3k)!}{k!^3}\binom n{3k}\binom{n+k}n \quad\text{for}\; n=0,1,2,\dots, \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \xi_n=\sum_{k=0}^n(-1)^{n-k}3^{n-3k}\frac{(3k)!}{k!^3}\binom n{3k}\binom{n+k}n \quad\text{for}\; n=0,1,2,\dots, \end{align*} $$

in the following sense. The three sequences satisfy similar difference equations of order 2 and degree 3, and their generating series

$$ \begin{align*} f_\alpha = \sum_{n=0}^\infty\alpha_n t^n, \quad f_\delta = \sum_{n=0}^\infty\delta_n t^n \quad\text{and}\quad f_\xi = \sum_{n=0}^\infty\xi_n t^n \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} f_\alpha = \sum_{n=0}^\infty\alpha_n t^n, \quad f_\delta = \sum_{n=0}^\infty\delta_n t^n \quad\text{and}\quad f_\xi = \sum_{n=0}^\infty\xi_n t^n \end{align*} $$

admit modular parametrisations via the Hauptmoduln of the three subgroups of index 2 lying between

![]() $\Gamma _0(6)$

and its normaliser in

$\Gamma _0(6)$

and its normaliser in

![]() $\operatorname {SL}_2(\mathbb R)$

(see [Reference Chan and Verrill7, Reference Chan and Zudilin8]).

$\operatorname {SL}_2(\mathbb R)$

(see [Reference Chan and Verrill7, Reference Chan and Zudilin8]).

Thanks to [Reference Chan and Zudilin8, Theorem 2.2], the argument for

![]() $f_\alpha $

extends to the series

$f_\alpha $

extends to the series

![]() $f_\delta $

and

$f_\delta $

and

![]() $f_\xi $

with the new relations:

$f_\xi $

with the new relations:

$$ \begin{align*} f_\delta = (1-8x) \cdot h^2 & \quad \text{with } t = \frac{x(1+x)}{1-8x}, \\ f_\xi = (1+x)(1-8x) \cdot h^2 & \quad \text{with } t = \frac{x}{(1+x)(1-8x)}. \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} f_\delta = (1-8x) \cdot h^2 & \quad \text{with } t = \frac{x(1+x)}{1-8x}, \\ f_\xi = (1+x)(1-8x) \cdot h^2 & \quad \text{with } t = \frac{x}{(1+x)(1-8x)}. \end{align*} $$

Theorem 1.3. Set

$$ \begin{align*} A_{\delta,p}=\sum_{n=0}^{p-1}\delta_nt^n\in\mathbb F_p[t]. \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} A_{\delta,p}=\sum_{n=0}^{p-1}\delta_nt^n\in\mathbb F_p[t]. \end{align*} $$

Then, there exists a polynomial

![]() $B_{\delta ,p} \in \mathbb {F}_p[t]$

such that:

$B_{\delta ,p} \in \mathbb {F}_p[t]$

such that:

-

• if

$p \equiv 1 \pmod {6}$

, then

$p \equiv 1 \pmod {6}$

, then

$A_{\delta ,p} = B_{\delta ,p}^2$

and

$A_{\delta ,p} = B_{\delta ,p}^2$

and

$\operatorname {\mathrm {Gal}}(\mathbb {F}_p(t, f_\delta )/\mathbb {F}_p(t)) = S$

;

$\operatorname {\mathrm {Gal}}(\mathbb {F}_p(t, f_\delta )/\mathbb {F}_p(t)) = S$

; -

• if

$p \equiv 5 \pmod {6}$

, then

$p \equiv 5 \pmod {6}$

, then

$A_{\delta ,p} = (64t^2-20t+1) B_{\delta ,p}^2$

and

$A_{\delta ,p} = (64t^2-20t+1) B_{\delta ,p}^2$

and

$\operatorname {\mathrm {Gal}}(\mathbb {F}_p(t, f_\delta )/\mathbb {F}_p(t)) = \mathbb {F}_p^\times $

.

$\operatorname {\mathrm {Gal}}(\mathbb {F}_p(t, f_\delta )/\mathbb {F}_p(t)) = \mathbb {F}_p^\times $

.

Theorem 1.4. Set

$$ \begin{align*} A_{\xi,p}=\sum_{n=0}^{p-1}\xi_nt^n\in\mathbb F_p[t]. \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} A_{\xi,p}=\sum_{n=0}^{p-1}\xi_nt^n\in\mathbb F_p[t]. \end{align*} $$

Then, there exists a polynomial

![]() $B_{\xi ,p} \in \mathbb {F}_p[t]$

such that:

$B_{\xi ,p} \in \mathbb {F}_p[t]$

such that:

-

• if

$p \equiv 1,3 \pmod {8}$

, then

$p \equiv 1,3 \pmod {8}$

, then

$A_{\xi ,p} = B_{\xi ,p}^2$

and

$A_{\xi ,p} = B_{\xi ,p}^2$

and

$\operatorname {\mathrm {Gal}}(\mathbb {F}_p(t, f_\xi )/\mathbb {F}_p(t)) = S$

;

$\operatorname {\mathrm {Gal}}(\mathbb {F}_p(t, f_\xi )/\mathbb {F}_p(t)) = S$

; -

• if

$p \equiv 5,7 \pmod {8}$

, then

$p \equiv 5,7 \pmod {8}$

, then

$A_{\xi ,p} = (81t^2+14t+1) B_{\xi ,p}^2$

and

$A_{\xi ,p} = (81t^2+14t+1) B_{\xi ,p}^2$

and

$\operatorname {\mathrm {Gal}}(\mathbb {F}_p(t, f_\xi )/\mathbb {F}_p(t)) = \mathbb {F}_p^\times $

.

$\operatorname {\mathrm {Gal}}(\mathbb {F}_p(t, f_\xi )/\mathbb {F}_p(t)) = \mathbb {F}_p^\times $

.

In Section 3.3, we collect more examples of series where we computationally observed similar patterns.

2 The Apéry numbers

Throughout this section, we fix an odd prime number p and set ![]() .

.

Lemma 2.1. The extension

![]() $\mathbb {F}_p(x)/\mathbb {F}_p(t)$

is a quadratic extension, which is generated by

$\mathbb {F}_p(x)/\mathbb {F}_p(t)$

is a quadratic extension, which is generated by

![]() $(t^2-34t+1)^{1/2}$

, with nontrivial element

$(t^2-34t+1)^{1/2}$

, with nontrivial element

![]() $\sigma :x\mapsto {(1-8x)}/{(8+8x)}$

of the Galois group.

$\sigma :x\mapsto {(1-8x)}/{(8+8x)}$

of the Galois group.

Proof. We note that x is a solution of the quadratic equation

![]() ${8x^2+(t-1)x+t=0}$

over

${8x^2+(t-1)x+t=0}$

over

![]() $\mathbb {F}_p(t)$

with discriminant

$\mathbb {F}_p(t)$

with discriminant

![]() $\Delta =t^2-34t+1$

. An easy calculation shows that

$\Delta =t^2-34t+1$

. An easy calculation shows that

![]() ${(1-8x)}/{(8+8x)}$

also solves this equation.

${(1-8x)}/{(8+8x)}$

also solves this equation.

Let

By Lucas’ theorem (on evaluating binomial coefficients modulo p), we easily check that the coefficients of h satisfy Lucas’ congruences and we deduce that

![]() $h=H h^p$

. Thus,

$h=H h^p$

. Thus,

![]() $h^2 = H^{-1/e}$

with

$h^2 = H^{-1/e}$

with ![]() .

.

Lemma 2.2. The polynomial H is not an nth power in

![]() $\mathbb {F}_p[x]$

for

$\mathbb {F}_p[x]$

for

![]() $n\geq 2$

.

$n\geq 2$

.

Proof. The series h satisfies the second-order differential equation

$$ \begin{align} x(x+1)(8x-1)\frac{d^2h}{dx^2} + (24x^2+14x-1) \frac{dh}{dx} + (8x+2)h = 0. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} x(x+1)(8x-1)\frac{d^2h}{dx^2} + (24x^2+14x-1) \frac{dh}{dx} + (8x+2)h = 0. \end{align} $$

By [Reference Caruso, Fürnsinn and Vargas-Montoya6, Lemma 2.1.3], H is not an eth power of a polynomial for any e, as soon as H has a root different from

![]() $0, -1, 1/8$

. One checks that H has degree

$0, -1, 1/8$

. One checks that H has degree

![]() $p-1$

and, using

$p-1$

and, using

![]() $\binom {p-1}{n}\equiv (-1)^n \pmod p$

, that it has leading coefficient

$\binom {p-1}{n}\equiv (-1)^n \pmod p$

, that it has leading coefficient

![]() $1$

. Also, it is clear that its constant coefficient is

$1$

. Also, it is clear that its constant coefficient is

![]() $1$

, so it does not have

$1$

, so it does not have

![]() $0$

as a root. Assuming that

$0$

as a root. Assuming that

for some m, we deduce by comparing the constant coefficients that

![]() $(-\tfrac 18)^m\equiv 1 \pmod p$

. Comparing the coefficient of x yields

$(-\tfrac 18)^m\equiv 1 \pmod p$

. Comparing the coefficient of x yields

so we deduce

![]() $m=(p-1)/3$

if

$m=(p-1)/3$

if

![]() $p\equiv 1 \pmod 3$

and

$p\equiv 1 \pmod 3$

and

![]() $m=(2p-1)/3$

otherwise. If

$m=(2p-1)/3$

otherwise. If

![]() $p\equiv 1 \pmod 3$

, we can then compare coefficients of

$p\equiv 1 \pmod 3$

, we can then compare coefficients of

![]() $x^2$

and find the contradiction

$x^2$

and find the contradiction

![]() $13\equiv 10\pmod p$

. If

$13\equiv 10\pmod p$

. If

![]() $p\equiv 2 \pmod 3$

, the contradiction already arises at the constant coefficient. Thus, H has a root different from

$p\equiv 2 \pmod 3$

, the contradiction already arises at the constant coefficient. Thus, H has a root different from

![]() $-1$

and

$-1$

and

![]() $1/8$

, and the claim follows.

$1/8$

, and the claim follows.

The field

![]() $\mathbb {F}_p(x)$

contains all eth roots of unity, where we keep the notation

$\mathbb {F}_p(x)$

contains all eth roots of unity, where we keep the notation

![]() ${e=(p-1)/2}$

, as they are already in

${e=(p-1)/2}$

, as they are already in

![]() $\mathbb {F}_p$

. Kummer theory then implies that the extension

$\mathbb {F}_p$

. Kummer theory then implies that the extension

![]() $\mathbb {F}_p(x, h^2)/\mathbb {F}_p(x)$

is an abelian extension of degree e whose Galois group is canonically isomorphic to S.

$\mathbb {F}_p(x, h^2)/\mathbb {F}_p(x)$

is an abelian extension of degree e whose Galois group is canonically isomorphic to S.

We now consider the tower of extensions:

and aim at studying the Galois properties of the total extension

![]() $\mathbb {F}_p(x,h^2)/\mathbb {F}_p(t)$

. To do this, we first determine the action of

$\mathbb {F}_p(x,h^2)/\mathbb {F}_p(t)$

. To do this, we first determine the action of

![]() $\sigma $

on H.

$\sigma $

on H.

Lemma 2.3. We have

$$ \begin{align*}H=\begin{cases} \sigma(H)\cdot (x+1)^{p-1} & \text{if } p\equiv 1 \pmod 6,\\ - \sigma(H)\cdot (x+1)^{p-1} & \text{if } p\equiv 5 \pmod 6. \end{cases}\end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}H=\begin{cases} \sigma(H)\cdot (x+1)^{p-1} & \text{if } p\equiv 1 \pmod 6,\\ - \sigma(H)\cdot (x+1)^{p-1} & \text{if } p\equiv 5 \pmod 6. \end{cases}\end{align*} $$

Proof. We first notice that

![]() $\sigma $

is an involution and that

$\sigma $

is an involution and that

![]() $G=\sigma (H) \cdot (x+1)^{p-1}$

is a polynomial of degree

$G=\sigma (H) \cdot (x+1)^{p-1}$

is a polynomial of degree

![]() $p-1$

. Additionally, one checks that H is a solution of the differential equation (2.1). Expressing G,

$p-1$

. Additionally, one checks that H is a solution of the differential equation (2.1). Expressing G,

![]() ${dG}/{dx}$

and

${dG}/{dx}$

and

![]() ${d^2G}/{dx^2}$

as

${d^2G}/{dx^2}$

as

![]() $\mathbb {F}_p(x)$

-linear combinations of

$\mathbb {F}_p(x)$

-linear combinations of

![]() $\sigma (H)$

and its successive derivatives (just by applying the chain and product rules), we find that G is also a solution of the same differential equation. Therefore, we must have

$\sigma (H)$

and its successive derivatives (just by applying the chain and product rules), we find that G is also a solution of the same differential equation. Therefore, we must have

with

![]() $a\in \mathbb {F}_p$

. Recalling that

$a\in \mathbb {F}_p$

. Recalling that

$$ \begin{align*} \sigma(H)=\sum_{n=0}^{p-1}\sum_{k=0}^n \binom{n}{k}^3\bigg(\frac{1-8x}{8+8x}\bigg)^n, \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \sigma(H)=\sum_{n=0}^{p-1}\sum_{k=0}^n \binom{n}{k}^3\bigg(\frac{1-8x}{8+8x}\bigg)^n, \end{align*} $$

we evaluate (2.2) at

![]() $x=-1$

to obtain

$x=-1$

to obtain

![]() $H_{|x=-1}=a$

. We set

$H_{|x=-1}=a$

. We set ![]() and introduce the hypergeometric series

and introduce the hypergeometric series

where ![]() denotes the Pochhammer symbol. We let also G denote the truncation at

denotes the Pochhammer symbol. We let also G denote the truncation at

![]() $y^p$

of g. Then,

$y^p$

of g. Then,

![]() $h={g}/{(1-2x)}$

(see [Reference Straub and Zudilin21, Example 3.4]). Moreover, g is p-Lucas as a series in y and thus

$h={g}/{(1-2x)}$

(see [Reference Straub and Zudilin21, Example 3.4]). Moreover, g is p-Lucas as a series in y and thus

![]() $G = g^{1-p}$

. From the fact that h is also p-Lucas, we deduce the equation

$G = g^{1-p}$

. From the fact that h is also p-Lucas, we deduce the equation

$$ \begin{align*} H=h^{1-p} = \frac{(1-2x)^{p-1}}{g^{p-1}}=(1-2x)^{p-1}G. \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} H=h^{1-p} = \frac{(1-2x)^{p-1}}{g^{p-1}}=(1-2x)^{p-1}G. \end{align*} $$

Evaluating this expression at

![]() $x=-1$

gives

$x=-1$

gives

![]() $a = G_{|x=-1} = G_{|y=1}$

.

$a = G_{|x=-1} = G_{|y=1}$

.

Thus, if

![]() $p\equiv 1 \pmod 3$

, that is,

$p\equiv 1 \pmod 3$

, that is,

![]() $p\equiv 1 \pmod 6$

, we obtain the congruences

$p\equiv 1 \pmod 6$

, we obtain the congruences

$$ \begin{align*}a\equiv \sum_{k=0}^{p-1}\binom{-1/3}{k}\binom{-2/3}{k} \equiv \sum_{k=0}^{p-1}\binom{(p-1)/3}{k}\binom{(2p-2)/3}{k}\equiv\binom{p-1}{(p-1)/3}\equiv 1 \pmod p.\end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}a\equiv \sum_{k=0}^{p-1}\binom{-1/3}{k}\binom{-2/3}{k} \equiv \sum_{k=0}^{p-1}\binom{(p-1)/3}{k}\binom{(2p-2)/3}{k}\equiv\binom{p-1}{(p-1)/3}\equiv 1 \pmod p.\end{align*} $$

If

![]() $p\equiv 2 \pmod 3$

, that is,

$p\equiv 2 \pmod 3$

, that is,

![]() $p\equiv 5 \pmod 6$

, we obtain similarly

$p\equiv 5 \pmod 6$

, we obtain similarly

$$ \begin{align*}a\equiv \sum_{k=0}^{p-1}\binom{-1/3}{k}\binom{-2/3}{k} \equiv \sum_{k=0}^{p-1}\binom{(2p-1)/3}{k}\binom{(p-2)/3}{k}\equiv\binom{p-1}{(p-1)/3}\equiv -1 \pmod p.\end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}a\equiv \sum_{k=0}^{p-1}\binom{-1/3}{k}\binom{-2/3}{k} \equiv \sum_{k=0}^{p-1}\binom{(2p-1)/3}{k}\binom{(p-2)/3}{k}\equiv\binom{p-1}{(p-1)/3}\equiv -1 \pmod p.\end{align*} $$

We have used the Chu–Vandermonde identity

![]() $\sum _{k=0}^r\binom {r}{k}\binom {s}{k}=\binom {r+s}{r}$

and the classical congruence

$\sum _{k=0}^r\binom {r}{k}\binom {s}{k}=\binom {r+s}{r}$

and the classical congruence

![]() $\binom {p{-}1}{k}\equiv (-1)^k \pmod p$

.

$\binom {p{-}1}{k}\equiv (-1)^k \pmod p$

.

Proposition 2.4. The field extension

![]() $\mathbb {F}_p(x,h^2)/\mathbb {F}_p(t)$

is an abelian Galois extension.

$\mathbb {F}_p(x,h^2)/\mathbb {F}_p(t)$

is an abelian Galois extension.

Proof. We first determine all the prolongations of

![]() $\sigma : \mathbb {F}_p(x) \to \mathbb {F}_p(x)$

to an automorphism of

$\sigma : \mathbb {F}_p(x) \to \mathbb {F}_p(x)$

to an automorphism of

![]() $\mathbb {F}_p(x, h^2)$

. Such a prolongation is uniquely determined by the value of

$\mathbb {F}_p(x, h^2)$

. Such a prolongation is uniquely determined by the value of

![]() $\sigma (h^2)$

, which needs to satisfy

$\sigma (h^2)$

, which needs to satisfy

![]() $\sigma (h^2)^e=\sigma (H)^{-1}$

. Thus,

$\sigma (h^2)^e=\sigma (H)^{-1}$

. Thus,

for some

![]() $u \in \mathbb {F}_p$

. Additionally, according to Lemma 2.3, u has to be a square if

$u \in \mathbb {F}_p$

. Additionally, according to Lemma 2.3, u has to be a square if

![]() ${p\equiv 1 \pmod 6}$

and not a square otherwise. Consequently, there are precisely e prolongations of the automorphism

${p\equiv 1 \pmod 6}$

and not a square otherwise. Consequently, there are precisely e prolongations of the automorphism

![]() $\sigma $

. There are clearly also e prolongations of the identity (given by the group S of squares in

$\sigma $

. There are clearly also e prolongations of the identity (given by the group S of squares in

![]() $\mathbb {F}_p$

acting by multiplication on

$\mathbb {F}_p$

acting by multiplication on

![]() $h^2$

). Hence, the extension

$h^2$

). Hence, the extension

![]() $\mathbb {F}_p(x,h^2)/\mathbb {F}_p(t)$

is Galois. Moreover, any prolongation of

$\mathbb {F}_p(x,h^2)/\mathbb {F}_p(t)$

is Galois. Moreover, any prolongation of

![]() $\sigma $

clearly commutes with any element of S, making the Galois group abelian.

$\sigma $

clearly commutes with any element of S, making the Galois group abelian.

Lemma 2.5. There exists a prolongation of

![]() $\sigma $

to

$\sigma $

to

![]() $\mathbb {F}_p(x, h^2)$

that is an involution if and only if one can take

$\mathbb {F}_p(x, h^2)$

that is an involution if and only if one can take

![]() $u=\pm \tfrac {8}{9}$

in (2.3).

$u=\pm \tfrac {8}{9}$

in (2.3).

Proof. We have

The claim follows.

Proposition 2.6. The Galois group of

![]() $\mathbb {F}_p(x,h^2)/\mathbb {F}_p(t)$

is

$\mathbb {F}_p(x,h^2)/\mathbb {F}_p(t)$

is

$$ \begin{align*}\operatorname{\mathrm{Gal}}(\mathbb{F}_p(x,h^2)/\mathbb{F}_p(t)) = \begin{cases} \mathbb{Z}/(p{-}1)\mathbb{Z}\simeq \mathbb{Z}/e\mathbb{Z}\times \mathbb{Z}/2\mathbb{Z} & \text{if } p\equiv 3 \pmod 4,\\ \mathbb{Z}/(p{-}1)\mathbb{Z} & \text{if } p\equiv 13, 17 \pmod {24},\\ \mathbb{Z}/e\mathbb{Z}\times \mathbb{Z}/2\mathbb{Z}& \text{if } p\equiv 1, 5 \pmod {24}. \end{cases} \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}\operatorname{\mathrm{Gal}}(\mathbb{F}_p(x,h^2)/\mathbb{F}_p(t)) = \begin{cases} \mathbb{Z}/(p{-}1)\mathbb{Z}\simeq \mathbb{Z}/e\mathbb{Z}\times \mathbb{Z}/2\mathbb{Z} & \text{if } p\equiv 3 \pmod 4,\\ \mathbb{Z}/(p{-}1)\mathbb{Z} & \text{if } p\equiv 13, 17 \pmod {24},\\ \mathbb{Z}/e\mathbb{Z}\times \mathbb{Z}/2\mathbb{Z}& \text{if } p\equiv 1, 5 \pmod {24}. \end{cases} \end{align*} $$

This corresponds respectively to the cases where precisely one of the two numbers

![]() ${u =\pm \frac {8}{9}}$

gives an involution

${u =\pm \frac {8}{9}}$

gives an involution

![]() $\sigma : h^2\mapsto u h^2 (1+x)^2$

in

$\sigma : h^2\mapsto u h^2 (1+x)^2$

in

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {Gal}}({}\mathbb {F}_p(x, h^2))/\mathbb {F}_p(t)$

, neither of them do or both of them do.

$\operatorname {\mathrm {Gal}}({}\mathbb {F}_p(x, h^2))/\mathbb {F}_p(t)$

, neither of them do or both of them do.

Proof. Note that

![]() $\frac {8}{9} = 2 \cdot (\tfrac 2 3)^2.$

Moreover,

$\frac {8}{9} = 2 \cdot (\tfrac 2 3)^2.$

Moreover,

![]() $2$

is a square modulo p if and only if

$2$

is a square modulo p if and only if

![]() ${p\equiv \pm 1 \pmod 8}$

and

${p\equiv \pm 1 \pmod 8}$

and

![]() $-1$

is a square modulo p if and only if

$-1$

is a square modulo p if and only if

![]() $p\equiv 1 \pmod 4$

.

$p\equiv 1 \pmod 4$

.

If

![]() $p\equiv 1 \pmod 6$

then, for any prolongation of

$p\equiv 1 \pmod 6$

then, for any prolongation of

![]() $\sigma $

, as in (2.3), u must be a square; if

$\sigma $

, as in (2.3), u must be a square; if

![]() $p\equiv 5 \pmod 6$

, the opposite must hold. As for

$p\equiv 5 \pmod 6$

, the opposite must hold. As for

![]() $p\equiv 3 \pmod 4$

, precisely one of the two values of

$p\equiv 3 \pmod 4$

, precisely one of the two values of

![]() $\pm \frac {8}{9}$

is a square, so we always have precisely one adequate choice for u. If

$\pm \frac {8}{9}$

is a square, so we always have precisely one adequate choice for u. If

![]() $p\equiv 1 \pmod 4$

, either both of them are a square or neither of them are.

$p\equiv 1 \pmod 4$

, either both of them are a square or neither of them are.

-

• If

$p\equiv 1 \pmod {24}$

, then u has to be a square and

$p\equiv 1 \pmod {24}$

, then u has to be a square and

$\pm \frac {8}{9}$

are both squares.

$\pm \frac {8}{9}$

are both squares. -

• If

$p\equiv 5 \pmod {24}$

, then u has to be a nonsquare and

$p\equiv 5 \pmod {24}$

, then u has to be a nonsquare and

$\pm \frac {8}{9}$

are both nonsquares.

$\pm \frac {8}{9}$

are both nonsquares. -

• If

$p\equiv 13 \pmod {24}$

, then u has to be a square, but

$p\equiv 13 \pmod {24}$

, then u has to be a square, but

$\pm \frac {8}{9}$

are both nonsquares.

$\pm \frac {8}{9}$

are both nonsquares. -

• If

$p\equiv 17 \pmod {24}$

, then u has to be a nonsquare, but

$p\equiv 17 \pmod {24}$

, then u has to be a nonsquare, but

$\pm \frac {8}{9}$

are both squares.

$\pm \frac {8}{9}$

are both squares.

This concludes the proof of the second statement.

For the first statement, we note that

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {Gal}}(\mathbb {F}_p(x,h^2)/\mathbb {F}_p(t))$

always contains a cyclic group of order e, corresponding to

$\operatorname {\mathrm {Gal}}(\mathbb {F}_p(x,h^2)/\mathbb {F}_p(t))$

always contains a cyclic group of order e, corresponding to

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {Gal}}(\mathbb {F}_p(x,h^2)/\mathbb {F}_p(x)) \simeq S$

. This leaves us only two possible choices: either

$\operatorname {\mathrm {Gal}}(\mathbb {F}_p(x,h^2)/\mathbb {F}_p(x)) \simeq S$

. This leaves us only two possible choices: either

![]() $\mathbb {Z}/(p-1)\mathbb {Z}$

or

$\mathbb {Z}/(p-1)\mathbb {Z}$

or

![]() $\mathbb {Z}/e\mathbb {Z}\times \mathbb {Z}/2\mathbb {Z}$

(which actually collapse in the case where

$\mathbb {Z}/e\mathbb {Z}\times \mathbb {Z}/2\mathbb {Z}$

(which actually collapse in the case where

![]() $p\equiv 3 \pmod 4$

). The direct factor

$p\equiv 3 \pmod 4$

). The direct factor

![]() $\mathbb {Z}/2\mathbb {Z}$

occurs if and only if there exists an element of the Galois group of order

$\mathbb {Z}/2\mathbb {Z}$

occurs if and only if there exists an element of the Galois group of order

![]() $2$

, which does not belong to S, that is, a prolongation of

$2$

, which does not belong to S, that is, a prolongation of

![]() $\sigma $

which is an involution. We conclude using Lemma 2.5.

$\sigma $

which is an involution. We conclude using Lemma 2.5.

We recall that

![]() $f=h^2\cdot (x+1)$

. This shows that

$f=h^2\cdot (x+1)$

. This shows that

![]() $\mathbb {F}_p(t, f)\subseteq \mathbb {F}_p(x, h^2).$

Moreover,

$\mathbb {F}_p(t, f)\subseteq \mathbb {F}_p(x, h^2).$

Moreover,

![]() $\mathbb {F}_p(t, f)$

is a cyclic extension of

$\mathbb {F}_p(t, f)$

is a cyclic extension of

![]() $\mathbb {F}_p(t)$

, of degree

$\mathbb {F}_p(t)$

, of degree

![]() $p-1$

or e, as explained in [Reference Caruso, Fürnsinn and Vargas-Montoya6, Subsection 2.1.5].

$p-1$

or e, as explained in [Reference Caruso, Fürnsinn and Vargas-Montoya6, Subsection 2.1.5].

Proof of Theorem 1.1

We distinguish cases according to the congruence class of p modulo

![]() $24$

.

$24$

.

-

• If

$p\equiv 1 \pmod {24}$

, the Galois group of

$p\equiv 1 \pmod {24}$

, the Galois group of

$\mathbb {F}_p(x, h^2)/\mathbb {F}_p(t)$

is not cyclic, according to Proposition 2.6. Thus,

$\mathbb {F}_p(x, h^2)/\mathbb {F}_p(t)$

is not cyclic, according to Proposition 2.6. Thus,

$\mathbb {F}_p(t, f)$

is a proper subfield of

$\mathbb {F}_p(t, f)$

is a proper subfield of

$\mathbb {F}_p(x, h^2)$

, necessarily of degree e over

$\mathbb {F}_p(x, h^2)$

, necessarily of degree e over

$\mathbb {F}_p(t)$

.

$\mathbb {F}_p(t)$

. -

• If

$p\equiv 5 \pmod {24}$

, the Galois group of

$p\equiv 5 \pmod {24}$

, the Galois group of

$\mathbb {F}_p(x, h^2)/\mathbb {F}_p(t)$

is not cyclic, according to Proposition 2.6. We conclude again that

$\mathbb {F}_p(x, h^2)/\mathbb {F}_p(t)$

is not cyclic, according to Proposition 2.6. We conclude again that

$\mathbb {F}_p(f,t)$

has degree e over

$\mathbb {F}_p(f,t)$

has degree e over

$\mathbb {F}_p(t)$

.

$\mathbb {F}_p(t)$

. -

• If

$p\equiv 7 \pmod {24}$

, the Galois group of

$p\equiv 7 \pmod {24}$

, the Galois group of

$\mathbb {F}_p(x, h^2)/\mathbb {F}_p(t)$

is cyclic, because e is odd. Then, we need to check whether f is in the unique subfield of

$\mathbb {F}_p(x, h^2)/\mathbb {F}_p(t)$

is cyclic, because e is odd. Then, we need to check whether f is in the unique subfield of

$\mathbb {F}_p(x, h^2)$

of index 2. This is equivalent to checking whether it is invariant under the unique element of the Galois group of order

$\mathbb {F}_p(x, h^2)$

of index 2. This is equivalent to checking whether it is invariant under the unique element of the Galois group of order

$2$

. According to Proposition 2.6, this element

$2$

. According to Proposition 2.6, this element

$\sigma $

is uniquely given as the prolongation of

$\sigma $

is uniquely given as the prolongation of

$x\mapsto {(1-8x)}/{(8+8x)}$

with

$x\mapsto {(1-8x)}/{(8+8x)}$

with

$\sigma (h^2)=u\cdot h^2\cdot (x+1)^2$

, where the prefactor u has to be

$\sigma (h^2)=u\cdot h^2\cdot (x+1)^2$

, where the prefactor u has to be

$\frac {8}{9}$

. We have

$\frac {8}{9}$

. We have  $$ \begin{align*}\textstyle \sigma(f)= \sigma(h^2) (\sigma(x)+1) = \frac{8}{9} h^2 (x+1)^2 (\sigma(x)+1) = h^2\cdot (x+1) = f.\end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}\textstyle \sigma(f)= \sigma(h^2) (\sigma(x)+1) = \frac{8}{9} h^2 (x+1)^2 (\sigma(x)+1) = h^2\cdot (x+1) = f.\end{align*} $$

So indeed, f is fixed by

$\sigma $

and the extension has degree e.

$\sigma $

and the extension has degree e. -

• If

$p\equiv 11 \pmod {24}$

, one proceeds as for

$p\equiv 11 \pmod {24}$

, one proceeds as for

$p \equiv 7 \pmod {24}$

, with the same conclusion.

$p \equiv 7 \pmod {24}$

, with the same conclusion. -

• If

$p\equiv 13 \pmod {24}$

, the group

$p\equiv 13 \pmod {24}$

, the group

$\operatorname {\mathrm {Gal}}(\mathbb {F}_p(x, h^2)/\mathbb {F}_p(t))$

is cyclic and the unique element of order

$\operatorname {\mathrm {Gal}}(\mathbb {F}_p(x, h^2)/\mathbb {F}_p(t))$

is cyclic and the unique element of order

$2$

in the Galois group is an element of S, sending

$2$

in the Galois group is an element of S, sending

$h^2$

to

$h^2$

to

$-h^2$

. Thus, f is not fixed and

$-h^2$

. Thus, f is not fixed and

$\mathbb {F}_p(t, f)\simeq \mathbb {F}_p(x, h^2)$

, having degree

$\mathbb {F}_p(t, f)\simeq \mathbb {F}_p(x, h^2)$

, having degree

$p-1$

over

$p-1$

over

$\mathbb {F}_p(t)$

.

$\mathbb {F}_p(t)$

. -

• The case

$p\equiv 17 \pmod {24}$

works as

$p\equiv 17 \pmod {24}$

works as

$p\equiv 13 \pmod {24}$

, with the same conclusion.

$p\equiv 13 \pmod {24}$

, with the same conclusion. -

• If

$p\equiv 19 \pmod {24}$

, we proceed as in the case

$p\equiv 19 \pmod {24}$

, we proceed as in the case

$p\equiv 7 \pmod {24}$

, with the exception that

$p\equiv 7 \pmod {24}$

, with the exception that

$u=-\frac {8}{9}$

. Thus,

$u=-\frac {8}{9}$

. Thus,

$\sigma (f)=-f$

and f is not in the unique subfield of index

$\sigma (f)=-f$

and f is not in the unique subfield of index

$2$

of

$2$

of

$\mathbb {F}_p(x, h^2)$

. Thus,

$\mathbb {F}_p(x, h^2)$

. Thus,

$\mathbb {F}_p(t, f)$

has degree

$\mathbb {F}_p(t, f)$

has degree

$p-1$

.

$p-1$

. -

• If

$p\equiv 23 \pmod {24}$

, we proceed as for

$p\equiv 23 \pmod {24}$

, we proceed as for

$p\equiv 19 \pmod {24}$

, as

$p\equiv 19 \pmod {24}$

, as

$u=-\frac {8}{9}$

again.

$u=-\frac {8}{9}$

again.

This concludes the proof.

Proof of Theorem 1.2

We recall that we have

![]() $f = (1+x) h^2$

in

$f = (1+x) h^2$

in

![]() $\mathbb {F}_p(t,f)$

. Therefore,

$\mathbb {F}_p(t,f)$

. Therefore,

![]() $f^e = (1+x)^e H \in \mathbb {F}_p(x)$

, from which we deduce that

$f^e = (1+x)^e H \in \mathbb {F}_p(x)$

, from which we deduce that

![]() $A_p = (1+x)^{p-1} H^2$

. In particular,

$A_p = (1+x)^{p-1} H^2$

. In particular,

![]() $A_p$

is a square in

$A_p$

is a square in

![]() $\mathbb {F}_p(x)$

. Since moreover

$\mathbb {F}_p(x)$

. Since moreover

![]() $\mathbb {F}_p(x)=\mathbb {F}_p(t, \sqrt {\Delta })$

with

$\mathbb {F}_p(x)=\mathbb {F}_p(t, \sqrt {\Delta })$

with

![]() ${\Delta = t^2-34t+1}$

, we can write

${\Delta = t^2-34t+1}$

, we can write

![]() $A_p=(u+v\sqrt {\Delta })^2$

for

$A_p=(u+v\sqrt {\Delta })^2$

for

![]() $u, v\in \mathbb {F}_p(t)$

. As

$u, v\in \mathbb {F}_p(t)$

. As

![]() $A_p\in \mathbb {F}_p(t),$

we must necessarily have

$A_p\in \mathbb {F}_p(t),$

we must necessarily have

![]() $2uv=0$

. Hence, either

$2uv=0$

. Hence, either

![]() $u = 0$

, in which case

$u = 0$

, in which case

![]() $A_p = (t^2-34t+1) v^2$

, or

$A_p = (t^2-34t+1) v^2$

, or

![]() $v = 0$

, in which case

$v = 0$

, in which case

![]() $A_p = u^2$

. Given that

$A_p = u^2$

. Given that

![]() $A_p$

is a square in

$A_p$

is a square in

![]() $\mathbb {F}_p(t)$

if and only if the extension

$\mathbb {F}_p(t)$

if and only if the extension

![]() $\mathbb {F}_p(t,f)/\mathbb {F}_p(t)$

has degree e, we conclude using Theorem 1.1.

$\mathbb {F}_p(t,f)/\mathbb {F}_p(t)$

has degree e, we conclude using Theorem 1.1.

3 Adaptation to Apéry-like sequences

The generalised Apéry numbers

![]() $a_n(r,s)=\sum _{k=0}^n \binom {n}{k}^r \binom {n+k}{n}^s$

are p-Lucas for all primes p [Reference Deutsch and Sagan14]. So

$a_n(r,s)=\sum _{k=0}^n \binom {n}{k}^r \binom {n+k}{n}^s$

are p-Lucas for all primes p [Reference Deutsch and Sagan14]. So

![]() $f_{r,s}=A_{r,s} f_{r,s}^p$

for the generating series

$f_{r,s}=A_{r,s} f_{r,s}^p$

for the generating series

![]() $f_{r,s}$

of

$f_{r,s}$

of

![]() $a_n(r,s)$

and its truncation

$a_n(r,s)$

and its truncation

![]() $A_{r,s}$

at order p. For

$A_{r,s}$

at order p. For

![]() $(r,s)\in \{(0,0), (1, 0), (0,1), (1,1), (2,0)\}$

, the generating function

$(r,s)\in \{(0,0), (1, 0), (0,1), (1,1), (2,0)\}$

, the generating function

![]() $f_{r,s}$

is algebraic. (For

$f_{r,s}$

is algebraic. (For

![]() $(r,s)=(0,1)$

, it is given by

$(r,s)=(0,1)$

, it is given by

![]() $(2t)^{-1}((1-4t)^{-1/2}-1)$

; for

$(2t)^{-1}((1-4t)^{-1/2}-1)$

; for

![]() $(r,s)=(1,1)$

, it is given by

$(r,s)=(1,1)$

, it is given by

![]() $(1 - 6t + t^2)^{-1/2}$

; and for

$(1 - 6t + t^2)^{-1/2}$

; and for

![]() $(r,s)=(2,0)$

, it is given by

$(r,s)=(2,0)$

, it is given by

![]() $(1-4t)^{-1/2}$

.) Only for the cases

$(1-4t)^{-1/2}$

.) Only for the cases

![]() $(r,s)\in \{(2,2), (4,0)\}$

, we computationally observed that

$(r,s)\in \{(2,2), (4,0)\}$

, we computationally observed that

![]() $A_{r,s}$

is a square for a class of prime numbers depending on some congruence conditions: the case

$A_{r,s}$

is a square for a class of prime numbers depending on some congruence conditions: the case

![]() $(r,s)=(2,2)$

is the regular Apéry numbers, and the case

$(r,s)=(2,2)$

is the regular Apéry numbers, and the case

![]() $(r,s)=(4,0)$

is studied in Section 3.3 (see level

$(r,s)=(4,0)$

is studied in Section 3.3 (see level

![]() $10$

in Table 2). So generalising the investigation in this direction does not show many new interesting patterns.

$10$

in Table 2). So generalising the investigation in this direction does not show many new interesting patterns.

As explained in the introduction, the Domb numbers and the Almkvist–Zudilin numbers are closely related to Apéry numbers. The proofs of very similar patterns, as stated in Theorems 1.3 and 1.4, proceed analogously to the Apéry case. We report in Sections 3.1 and 3.2 on the changes that need to be made.

In the last section, Section 3.3, more sequences of similar flavour are analysed.

3.1 The Domb numbers

We set ![]() . The relation to

. The relation to

![]() $h(x)$

is given by

$h(x)$

is given by

![]() ${(1-8x)}^{-1} f_\delta (t_\delta )=h(x)^2$

. In Lemma 2.1, we replace the involution

${(1-8x)}^{-1} f_\delta (t_\delta )=h(x)^2$

. In Lemma 2.1, we replace the involution

![]() $\sigma $

by

$\sigma $

by

![]() $\sigma _\delta :x\mapsto {(1+x)}/{(8x-1)}$

, and the generator of the field extension

$\sigma _\delta :x\mapsto {(1+x)}/{(8x-1)}$

, and the generator of the field extension

![]() $\mathbb {F}_p(x)/\mathbb {F}_p(t_\delta )$

is

$\mathbb {F}_p(x)/\mathbb {F}_p(t_\delta )$

is

![]() $(64t_\delta ^2-20t_\delta +1)^{1/2}$

.

$(64t_\delta ^2-20t_\delta +1)^{1/2}$

.

As in Lemma 2.3, we obtain

$$ \begin{align*}H=\begin{cases} \sigma_\delta(H)\cdot (8x-1)^{p-1} & \text{if } p\equiv 1 \pmod 6,\\ - \sigma_\delta(H)\cdot (8x-1)^{p-1} & \text{if } p\equiv 5 \pmod 6. \end{cases}\end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}H=\begin{cases} \sigma_\delta(H)\cdot (8x-1)^{p-1} & \text{if } p\equiv 1 \pmod 6,\\ - \sigma_\delta(H)\cdot (8x-1)^{p-1} & \text{if } p\equiv 5 \pmod 6. \end{cases}\end{align*} $$

In Lemma 2.5, the automorphism

![]() $\sigma _\delta $

can be extended as

$\sigma _\delta $

can be extended as

![]() $\sigma _\delta (h^2)=u \cdot h^2 \cdot (8x-1)^2$

for u being either a square or a nonsquare, depending on the congruence class of

$\sigma _\delta (h^2)=u \cdot h^2 \cdot (8x-1)^2$

for u being either a square or a nonsquare, depending on the congruence class of

![]() $p\bmod 6$

. Such a prolongation is an involution on

$p\bmod 6$

. Such a prolongation is an involution on

![]() $\mathbb {F}_p(x, h^2)$

if and only if one can take

$\mathbb {F}_p(x, h^2)$

if and only if one can take

![]() $u=\pm \frac {1}{9}$

. One of these values is always a square, while the other one is a square if and only if

$u=\pm \frac {1}{9}$

. One of these values is always a square, while the other one is a square if and only if

![]() $p\equiv 1 \pmod 4$

. Thus,

$p\equiv 1 \pmod 4$

. Thus,

$$ \begin{align*}\operatorname{\mathrm{Gal}}(\mathbb{F}_p(x, h^2)/\mathbb{F}_p(t_\delta)) = \begin{cases} \mathbb{Z}/(p-1)\mathbb{Z}\simeq \mathbb{Z}/e\mathbb{Z}\times \mathbb{Z}/2\mathbb{Z} & \text{if } p\equiv 7, 11 \pmod{12},\\ \mathbb{Z}/(p-1)\mathbb{Z} & \text{if } p\equiv 5 \pmod{12},\\ \mathbb{Z}/e\mathbb{Z}\times \mathbb{Z}/2\mathbb{Z}& \text{if } p\equiv 1 \pmod{12}, \end{cases} \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}\operatorname{\mathrm{Gal}}(\mathbb{F}_p(x, h^2)/\mathbb{F}_p(t_\delta)) = \begin{cases} \mathbb{Z}/(p-1)\mathbb{Z}\simeq \mathbb{Z}/e\mathbb{Z}\times \mathbb{Z}/2\mathbb{Z} & \text{if } p\equiv 7, 11 \pmod{12},\\ \mathbb{Z}/(p-1)\mathbb{Z} & \text{if } p\equiv 5 \pmod{12},\\ \mathbb{Z}/e\mathbb{Z}\times \mathbb{Z}/2\mathbb{Z}& \text{if } p\equiv 1 \pmod{12}, \end{cases} \end{align*} $$

again corresponding respectively to the case of one, zero or two prolongations of

![]() $\sigma _\delta $

to an involution on

$\sigma _\delta $

to an involution on

![]() $\mathbb {F}_p(x, h^2)$

.

$\mathbb {F}_p(x, h^2)$

.

Finally,

![]() $f_\delta \in \mathbb {F}_p(x, h^2)$

because of the relations stated above. We distinguish the following cases.

$f_\delta \in \mathbb {F}_p(x, h^2)$

because of the relations stated above. We distinguish the following cases.

-

• If

$p\equiv 1\pmod {12}$

, then the Galois group of

$p\equiv 1\pmod {12}$

, then the Galois group of

$\mathbb {F}_p(x, h^2)/\mathbb {F}_p(t_\delta )$

is not cyclic and

$\mathbb {F}_p(x, h^2)/\mathbb {F}_p(t_\delta )$

is not cyclic and

$\mathbb {F}_p(t_\delta , f_\delta )$

is a subfield of

$\mathbb {F}_p(t_\delta , f_\delta )$

is a subfield of

$\mathbb {F}_p(x, h^2)$

of order e.

$\mathbb {F}_p(x, h^2)$

of order e. -

• If

$p\equiv 5\pmod {12}$

, then the Galois group

$p\equiv 5\pmod {12}$

, then the Galois group

$\mathbb {F}_p(x, h^2)/\mathbb {F}_p(t_\delta )$

is cyclic. The question then becomes to determine whether

$\mathbb {F}_p(x, h^2)/\mathbb {F}_p(t_\delta )$

is cyclic. The question then becomes to determine whether

$f_\delta $

is fixed by

$f_\delta $

is fixed by

$\sigma _\delta $

. However, the unique element of order

$\sigma _\delta $

. However, the unique element of order

$2$

in the group in this case belongs to the group S sending

$2$

in the group in this case belongs to the group S sending

$h^2$

to

$h^2$

to

$-h^2$

and thus

$-h^2$

and thus

$f_\delta $

is not fixed.

$f_\delta $

is not fixed. -

• If

$p \equiv 7 \pmod {12}$

, then the Galois group of

$p \equiv 7 \pmod {12}$

, then the Galois group of

$\mathbb {F}_p(x, h^2)/\mathbb {F}_p(t_\delta )$

is cyclic. There is one involution extending

$\mathbb {F}_p(x, h^2)/\mathbb {F}_p(t_\delta )$

is cyclic. There is one involution extending

$\sigma _\delta $

, corresponding to

$\sigma _\delta $

, corresponding to

$u=\frac {1}{9}$

. We compute so

$u=\frac {1}{9}$

. We compute so $$ \begin{align*}\textstyle \sigma_\delta(f_\delta)= \sigma_\delta(h^2) (1-8\sigma_\delta(x)) = \frac{1}{9} h^2 (1-8x)^2 (1-8\sigma_\delta(x)) = h^2\cdot (1-8x) = f_\delta,\end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}\textstyle \sigma_\delta(f_\delta)= \sigma_\delta(h^2) (1-8\sigma_\delta(x)) = \frac{1}{9} h^2 (1-8x)^2 (1-8\sigma_\delta(x)) = h^2\cdot (1-8x) = f_\delta,\end{align*} $$

$f_\delta $

is fixed and thus contained in a proper subfield of

$f_\delta $

is fixed and thus contained in a proper subfield of

$\mathbb {F}_p(x, h^2)$

of order e.

$\mathbb {F}_p(x, h^2)$

of order e.

-

• If

$p \equiv 11 \pmod {12}$

, the prolongation of

$p \equiv 11 \pmod {12}$

, the prolongation of

$\sigma _\delta $

corresponds to

$\sigma _\delta $

corresponds to

$u=-\frac {1}{9}$

and, this time,

$u=-\frac {1}{9}$

and, this time,

$f_\delta $

changes sign under

$f_\delta $

changes sign under

$\sigma _\delta $

.

$\sigma _\delta $

.

3.2 The Almkvist–Zudilin numbers

For the Almkvist–Zudilin numbers, we set ![]() and find the involution

and find the involution ![]() of

of

![]() $\mathbb {F}_p(x)$

fixing

$\mathbb {F}_p(x)$

fixing

![]() $\mathbb {F}_p(t_\xi )$

. This time, we obtain the simple relation

$\mathbb {F}_p(t_\xi )$

. This time, we obtain the simple relation

![]() $H=\sigma (H)\cdot x^{p-1}$

for all prime numbers p. The involution

$H=\sigma (H)\cdot x^{p-1}$

for all prime numbers p. The involution

![]() $\sigma _\xi $

can be extended to

$\sigma _\xi $

can be extended to

![]() $\mathbb {F}_p(x, h^2)$

by

$\mathbb {F}_p(x, h^2)$

by

![]() $\sigma _\xi (h)^2=u h^2 x^2$

with

$\sigma _\xi (h)^2=u h^2 x^2$

with

![]() $u\in S$

; it is an involution if and only if we can take

$u\in S$

; it is an involution if and only if we can take

![]() $u=\pm 8$

. Now,

$u=\pm 8$

. Now,

![]() $8$

is a square if and only if

$8$

is a square if and only if

![]() $p\equiv \pm 1 \pmod 8$

and

$p\equiv \pm 1 \pmod 8$

and

![]() $-1$

is a square if and only if

$-1$

is a square if and only if

![]() $p\equiv 1 \pmod 4$

. Thus,

$p\equiv 1 \pmod 4$

. Thus,

$$ \begin{align*} \operatorname{\mathrm{Gal}}(\mathbb{F}_p(x, h^2)/\mathbb{F}_p(t_\xi)) = \begin{cases} \mathbb{Z}/(p-1)\mathbb{Z}\simeq \mathbb{Z}/e\mathbb{Z}\times \mathbb{Z}/2\mathbb{Z} & \text{if } p\equiv 3,7 \pmod 8,\\ \mathbb{Z}/(p-1)\mathbb{Z} & \text{if } p\equiv 5 \pmod 8,\\ \mathbb{Z}/e\mathbb{Z}\times \mathbb{Z}/2\mathbb{Z}& \text{if } p\equiv 1 \pmod 8. \end{cases} \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \operatorname{\mathrm{Gal}}(\mathbb{F}_p(x, h^2)/\mathbb{F}_p(t_\xi)) = \begin{cases} \mathbb{Z}/(p-1)\mathbb{Z}\simeq \mathbb{Z}/e\mathbb{Z}\times \mathbb{Z}/2\mathbb{Z} & \text{if } p\equiv 3,7 \pmod 8,\\ \mathbb{Z}/(p-1)\mathbb{Z} & \text{if } p\equiv 5 \pmod 8,\\ \mathbb{Z}/e\mathbb{Z}\times \mathbb{Z}/2\mathbb{Z}& \text{if } p\equiv 1 \pmod 8. \end{cases} \end{align*} $$

Finally,

![]() $f_\xi \in \mathbb {F}_p(x, h^2)$

and investigations depending on the congruence class of

$f_\xi \in \mathbb {F}_p(x, h^2)$

and investigations depending on the congruence class of

![]() $p\pmod 8$

yield the following statements.

$p\pmod 8$

yield the following statements.

-

• If

$p\equiv 1 \pmod 8$

, the Galois group

$p\equiv 1 \pmod 8$

, the Galois group

$\operatorname {\mathrm {Gal}}(\mathbb {F}_p(x, h^2)/\mathbb {F}_p(t_\xi ))$

is not cyclic and thus,

$\operatorname {\mathrm {Gal}}(\mathbb {F}_p(x, h^2)/\mathbb {F}_p(t_\xi ))$

is not cyclic and thus,

$f_\xi $

is in a proper subfield of degree e.

$f_\xi $

is in a proper subfield of degree e. -

• If

$p\equiv 3 \pmod 8$

, the unique prolongation of

$p\equiv 3 \pmod 8$

, the unique prolongation of

$\sigma _\xi $

as an involution corresponds to

$\sigma _\xi $

as an involution corresponds to

$u=-8$

and because of we conclude that

$u=-8$

and because of we conclude that $$ \begin{align*}\textstyle \sigma_\xi (f_\xi)= \sigma(h^2) (1+\sigma_\xi(x))(1-8\sigma_\xi(x)) = h^2 (1-8x)(1+x)= f_\xi,\end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}\textstyle \sigma_\xi (f_\xi)= \sigma(h^2) (1+\sigma_\xi(x))(1-8\sigma_\xi(x)) = h^2 (1-8x)(1+x)= f_\xi,\end{align*} $$

$f_\xi $

lies in a proper subfield of

$f_\xi $

lies in a proper subfield of

$\mathbb {F}_p(x, h^2)$

of degree e.

$\mathbb {F}_p(x, h^2)$

of degree e.

-

• If

$p\equiv 5 \pmod 8$

, the unique element of order

$p\equiv 5 \pmod 8$

, the unique element of order

$2$

in

$2$

in

$\operatorname {\mathrm {Gal}}({}\mathbb {F}_p(x, h^2))/\mathbb {F}_p(t_\xi )$

belongs to the subgroup of squares of

$\operatorname {\mathrm {Gal}}({}\mathbb {F}_p(x, h^2))/\mathbb {F}_p(t_\xi )$

belongs to the subgroup of squares of

$\mathbb {F}_p^\times $

and sends h to

$\mathbb {F}_p^\times $

and sends h to

$-h$

and thus does not fix

$-h$

and thus does not fix

$f_\xi $

. So

$f_\xi $

. So

$\mathbb {F}_p(t_\xi , f_\xi )=\mathbb {F}_p(x, h)$

.

$\mathbb {F}_p(t_\xi , f_\xi )=\mathbb {F}_p(x, h)$

. -

• If

$p\equiv 7 \pmod 8$

, the prolongation of

$p\equiv 7 \pmod 8$

, the prolongation of

$\sigma _\xi $

as an involution corresponds to

$\sigma _\xi $

as an involution corresponds to

$u=+8$

and, this time,

$u=+8$

and, this time,

$f_\xi $

changes sign under it and thus is not fixed by it. Again,

$f_\xi $

changes sign under it and thus is not fixed by it. Again,

$\mathbb {F}_p(t_\xi , f_\xi )=\mathbb {F}_p(x, h)$

.

$\mathbb {F}_p(t_\xi , f_\xi )=\mathbb {F}_p(x, h)$

.

3.3 A zoo of further examples

In this section, we present further sequences which seem to exhibit similar, sometimes a bit more intricate, patterns as the three sequences we discussed so far. Our observations are of a computational nature, although we believe that working out proofs deploying similar techniques is possible.

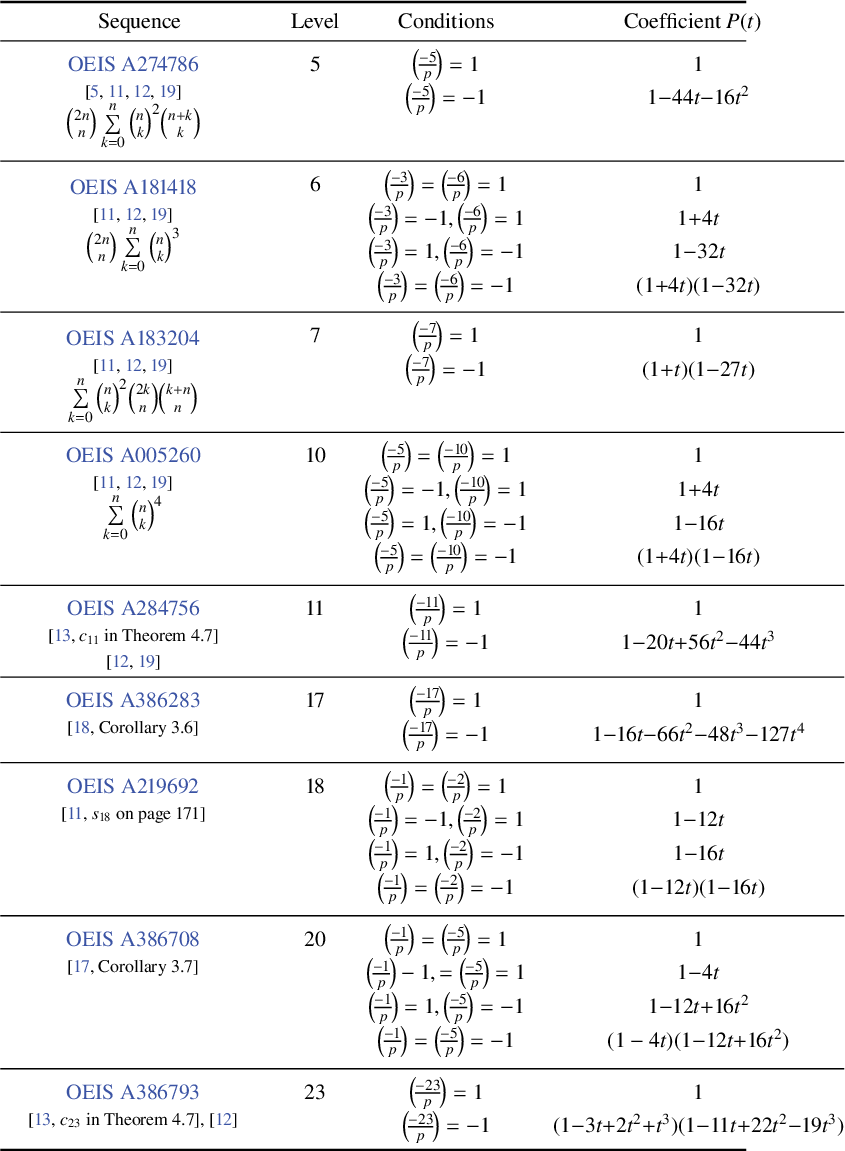

First, we consider the three other sequences of Zagier’s sporadic examples of integral sequences satisfying a three-term recurrence relation [Reference Zagier, Harnad and Winternitz24]. It is known that these sequences are p-Lucas for all primes p [Reference Malik and Straub20]; therefore, their generating series

![]() $f(t)$

satisfies the relation

$f(t)$

satisfies the relation

![]() $f(t) \equiv A_p(t) f(t)^p \pmod p$

, where

$f(t) \equiv A_p(t) f(t)^p \pmod p$

, where

![]() $A_p(t) \in \mathbb {F}_p[t]$

is the truncation at

$A_p(t) \in \mathbb {F}_p[t]$

is the truncation at

![]() $t^p$

of

$t^p$

of

![]() $f(t) \bmod p$

. As before, we are interested in the factorisation of

$f(t) \bmod p$

. As before, we are interested in the factorisation of

![]() $A_p(t)$

of the form

$A_p(t)$

of the form

![]() $A_p(t) = P(t) B_p(t)^2$

. Table 1 shows how

$A_p(t) = P(t) B_p(t)^2$

. Table 1 shows how

![]() $P(t)$

seems to vary with respect to p.

$P(t)$

seems to vary with respect to p.

Table 1 Zagier’s sporadic examples [Reference Almkvist, van Straten and Zudilin2, Reference Zagier, Harnad and Winternitz24].

Table 2 Examples of sequences connected to modular forms.

We pursue our investigations with other sequences associated to modular functions (of a given level) in Table 2. Thanks to [Reference Adamczewski, Bell and Delaygue1, Reference Beukers, Tsai and Ye4], all the series appearing in this table are p-Lucas except for levels

![]() $17$

,

$17$

,

![]() $20$

and

$20$

and

![]() $23$

. However, in these cases, they continue to satisfy a relation of the form

$23$

. However, in these cases, they continue to satisfy a relation of the form

![]() $f(t) \equiv A_p(t) f(t)^p \pmod p$

, where now,

$f(t) \equiv A_p(t) f(t)^p \pmod p$

, where now,

![]() $A_p(t) \in \mathbb {F}_p(t)$

is a rational function; this follows from the main theorem of [Reference Vargas-Montoya23]. As a conclusion, in all cases,

$A_p(t) \in \mathbb {F}_p(t)$

is a rational function; this follows from the main theorem of [Reference Vargas-Montoya23]. As a conclusion, in all cases,

![]() $A_p(t)$

is well defined and it makes sense to study its factorisation as

$A_p(t)$

is well defined and it makes sense to study its factorisation as

![]() ${A_p(t) = P(t) B_p(t)^2}$

as before.

${A_p(t) = P(t) B_p(t)^2}$

as before.

In all the examples of Tables 1 and 2, we computationally observed that the patterns for the polynomials

![]() $P(t)$

depend on explicit quadratic residue conditions for the prime p. These patterns are very much in line with those recorded in Theorems 1.1, 1.2, 1.3 and 1.4, and we are confident that one can apply, case by case, a similar strategy to establish the claims in the tables rigorously. The principal feature of the underlying series

$P(t)$

depend on explicit quadratic residue conditions for the prime p. These patterns are very much in line with those recorded in Theorems 1.1, 1.2, 1.3 and 1.4, and we are confident that one can apply, case by case, a similar strategy to establish the claims in the tables rigorously. The principal feature of the underlying series

![]() $f(t)$

is the presence of suitable rational parametrisations

$f(t)$

is the presence of suitable rational parametrisations

![]() $t=t(x)$

such that

$t=t(x)$

such that

![]() $f(t(x))=\rho (x)h(x)^2$

for a function

$f(t(x))=\rho (x)h(x)^2$

for a function

![]() $h(x)$

solving a second-order linear differential equation and, in turn, related to an arithmetic

$h(x)$

solving a second-order linear differential equation and, in turn, related to an arithmetic

![]() $_2F_1$

hypergeometric function

$_2F_1$

hypergeometric function

![]() $g(y)$

via another parametrisation

$g(y)$

via another parametrisation

![]() $y=y(x)$

, namely,

$y=y(x)$

, namely,

![]() $h(x)=\lambda (x)g(y(x))$

. In Apéry’s case (but also for the Domb and Almkvist–Zudilin sequences), all the intermediate functions are rational in x:

$h(x)=\lambda (x)g(y(x))$

. In Apéry’s case (but also for the Domb and Almkvist–Zudilin sequences), all the intermediate functions are rational in x:

$$ \begin{align*} t(x)=\frac{x(1-8x)}{1+x}, \quad \rho(x)=1+x, \quad y(x)=\frac{27x^2}{(1-2x)^3}, \quad \lambda(x)=\frac1{1-2x}. \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} t(x)=\frac{x(1-8x)}{1+x}, \quad \rho(x)=1+x, \quad y(x)=\frac{27x^2}{(1-2x)^3}, \quad \lambda(x)=\frac1{1-2x}. \end{align*} $$

However, in general,

![]() $\rho (x)$

,

$\rho (x)$

,

![]() $y(x)$

and

$y(x)$

and

![]() $\lambda (x)$

are algebraic, which can make the structure of the corresponding Galois group more involved. The existence of such x-parametrisations is a consequence of modular parametrisations of all such Apéry-like sequences; the details of the latter can be found in the corresponding references from which our examples originate. We leave the details to the interested reader as exercises.

$\lambda (x)$

are algebraic, which can make the structure of the corresponding Galois group more involved. The existence of such x-parametrisations is a consequence of modular parametrisations of all such Apéry-like sequences; the details of the latter can be found in the corresponding references from which our examples originate. We leave the details to the interested reader as exercises.

Going further, the observations on the splitting pattern of

![]() $A_p(t)$

as

$A_p(t)$

as

![]() $P(t)B_p(t)^2$

suggest that the conditions on p depend only on the quadratic residues of the negative divisors of the squarefree part of the corresponding level. We also leave it to the interested reader to formulate and prove a precise statement about the pattern that unfolds here. We conclude by remarking that these observations provide more computational evidence for the conjectures that were formulated in [Reference Caruso, Fürnsinn and Vargas-Montoya6] on uniformity properties of Galois groups of reductions of D-finite series.

$P(t)B_p(t)^2$

suggest that the conditions on p depend only on the quadratic residues of the negative divisors of the squarefree part of the corresponding level. We also leave it to the interested reader to formulate and prove a precise statement about the pattern that unfolds here. We conclude by remarking that these observations provide more computational evidence for the conjectures that were formulated in [Reference Caruso, Fürnsinn and Vargas-Montoya6] on uniformity properties of Galois groups of reductions of D-finite series.

Acknowledgements

We thank Alin Bostan for his interest in this project and for pointing out that the Domb numbers and the Almkvist–Zudilin numbers share the same behaviour as the Apéry numbers. F.F. and W.Z. thank the Max Planck Institute for Mathematics (Bonn, Germany) for their hospitality and financial support in May 2025, where the initial discussion on the project commenced.