Refine search

Actions for selected content:

316 results

The 1582 Registro de Mulatos and the Politics of Labor and Race in Early Colonial Cusco, Peru

-

- Journal:

- Comparative Studies in Society and History , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 29 January 2026, pp. 1-29

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Peruvian Peasant Women and Revolutionary Movements: La Convención’s Classist Revolution

-

- Journal:

- Journal of Latin American Studies , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 08 January 2026, pp. 1-25

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Peruvian Grassroots Organizations in Times of Violence and Peace. Between Economic Solidarity, Participatory Democracy, and Feminism

-

- Journal:

- Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations / Volume 28 / Issue 3 / June 2017

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 01 January 2026, pp. 1249-1269

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Inclusive Innovations Through Social and Solidarity Economy Initiatives: A Process Analysis of a Peruvian Case Study

-

- Journal:

- Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations / Volume 27 / Issue 1 / February 2016

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 01 January 2026, pp. 61-85

-

- Article

- Export citation

“We have a lot of goodwill, but we still need to eat…”: Valuing Women’s Long Term Voluntarism in Community Development in Lima

-

- Journal:

- Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations / Volume 20 / Issue 1 / March 2009

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 01 January 2026, pp. 15-34

-

- Article

- Export citation

The Quest for Virile National Progress: Modernity, Masculinity, and Intraclass Disputes in Peruvian Intellectual Elites, 1884–1912

-

- Journal:

- Latin American Research Review ,

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 09 December 2025, pp. 1-18

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

6 - Gold Mining and Indigenous Conflicts in Madre de Dios, Peru

- from Part III - Narco-Gold Mining in the Amazon

-

- Book:

- Clearcut

- Published online:

- 03 October 2025

- Print publication:

- 02 October 2025, pp 117-139

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

7 - Tracking the Rising Role of Organized Crime in Gold Mining

- from Part III - Narco-Gold Mining in the Amazon

-

- Book:

- Clearcut

- Published online:

- 03 October 2025

- Print publication:

- 02 October 2025, pp 140-160

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Epilogue

- from Part V - Global Deforestation

-

- Book:

- Clearcut

- Published online:

- 03 October 2025

- Print publication:

- 02 October 2025, pp 266-270

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

1 - Theorizing Regionally Dominant Political and Moral Economies as Causes of Deforestation

- from Part I - Introduction

-

- Book:

- Clearcut

- Published online:

- 03 October 2025

- Print publication:

- 02 October 2025, pp 3-30

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

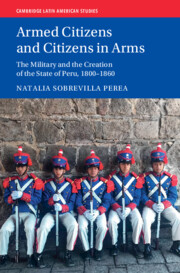

Armed Citizens and Citizens in Arms

- The Military and the Creation of the State of Peru, 1800‒1860

-

- Published online:

- 12 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 25 September 2025

Lock-in from within: Challenges to expanding cash transfer programs in Peru

-

- Journal:

- Journal of International and Comparative Social Policy , FirstView

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 03 September 2025, pp. 1-15

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Middle Holocene Salt Production on the North Coast of Peru

-

- Journal:

- Latin American Antiquity / Volume 36 / Issue 3 / September 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 03 November 2025, pp. 758-771

- Print publication:

- September 2025

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

7 - The Roots of Stable Authoritarianism

-

- Book:

- The Birth of Democracy in South America

- Published online:

- 04 June 2025

- Print publication:

- 07 August 2025, pp 224-261

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Introduction: Debating Guaman Poma: Questioning His Claims and Reframing His Historical Importance

-

- Journal:

- The Americas / Volume 82 / Issue 3 / July 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 14 January 2026, pp. 295-300

- Print publication:

- July 2025

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

8 - “Money for the Poor”

-

-

- Book:

- Governing Climate Change Loss and Damage

- Published online:

- 10 June 2025

- Print publication:

- 26 June 2025, pp 160-176

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

11 - The Political Economy of Investment Protection Reform in South American PTAs

-

-

- Book:

- Globalization in Latin America

- Published online:

- 09 June 2025

- Print publication:

- 26 June 2025, pp 231-254

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Identification of Dysmicoccus brevipes and its association with PMWaV-1, -2, and -3 in Hawaiiana cultivar and MD-2 hybrid pineapple in Peru

-

- Journal:

- Bulletin of Entomological Research / Volume 115 / Issue 5 / October 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 18 June 2025, pp. 537-544

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Population genetics of the endangered black walnut Juglans neotropica (Juglandaceae) based on plastid data from the Amazonas region

-

- Journal:

- Journal of Tropical Ecology / Volume 41 / 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 16 June 2025, e14

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation