Refine search

Actions for selected content:

53016 results in American studies

The No-Fly Zone in US Foreign Policy

- The Curious Persistence of a Flawed Instrument

-

- Published by:

- Bristol University Press

- Published online:

- 06 February 2026

- Print publication:

- 12 September 2025

Corporate Climate Adaptation

- Translating Complex Societal Risks into Business as Usual

-

- Published online:

- 06 February 2026

- Print publication:

- 05 March 2026

-

- Element

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

The Political Writings of Abraham Lincoln

-

- Published online:

- 04 February 2026

- Print publication:

- 19 February 2026

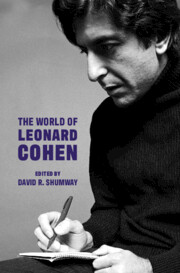

The World of Leonard Cohen

-

- Published online:

- 29 January 2026

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026

Part II - Musical Contexts

-

- Book:

- The World of Leonard Cohen

- Published online:

- 29 January 2026

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 75-122

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 2 - The Poetry and Prose

- from Part I - Creative Life

-

-

- Book:

- The World of Leonard Cohen

- Published online:

- 29 January 2026

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 29-46

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Part III - Religious Contexts

-

- Book:

- The World of Leonard Cohen

- Published online:

- 29 January 2026

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 123-164

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 14 - Neurotic Affiliations

- from Part IV - Cultural Contexts

-

-

- Book:

- The World of Leonard Cohen

- Published online:

- 29 January 2026

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 209-222

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 1 - The Life of a Troubadour

- from Part I - Creative Life

-

-

- Book:

- The World of Leonard Cohen

- Published online:

- 29 January 2026

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 13-28

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 13 - Cohen’s Cinematic Appeal

- from Part IV - Cultural Contexts

-

-

- Book:

- The World of Leonard Cohen

- Published online:

- 29 January 2026

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 195-208

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Further Reading

-

- Book:

- The World of Leonard Cohen

- Published online:

- 29 January 2026

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 366-369

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 22 - How to Be an Aged Rock Star

- from Part V - Reception and Legacy

-

-

- Book:

- The World of Leonard Cohen

- Published online:

- 29 January 2026

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 327-339

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 18 - Politics

- from Part IV - Cultural Contexts

-

-

- Book:

- The World of Leonard Cohen

- Published online:

- 29 January 2026

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 263-282

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 3 - Songwriting

- from Part I - Creative Life

-

-

- Book:

- The World of Leonard Cohen

- Published online:

- 29 January 2026

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 47-60

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Introduction

-

-

- Book:

- The World of Leonard Cohen

- Published online:

- 29 January 2026

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 1-10

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Part V - Reception and Legacy

-

- Book:

- The World of Leonard Cohen

- Published online:

- 29 January 2026

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 283-365

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Part IV - Cultural Contexts

-

- Book:

- The World of Leonard Cohen

- Published online:

- 29 January 2026

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 165-282

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 4 - Assembling Albums in the Tower of Song

- from Part I - Creative Life

-

-

- Book:

- The World of Leonard Cohen

- Published online:

- 29 January 2026

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 61-74

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 7 - Unrocking Rock & Roll

- from Part II - Musical Contexts

-

-

- Book:

- The World of Leonard Cohen

- Published online:

- 29 January 2026

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 109-122

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contents

-

- Book:

- The World of Leonard Cohen

- Published online:

- 29 January 2026

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp vii-ix

-

- Chapter

- Export citation