Refine search

Actions for selected content:

438599 results in Area Studies

Chapter 1 - Introduction

-

- Book:

- Family, Vocation, and Humanism in the Italian Renaissance

- Published online:

- 18 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 1-17

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Bibliography

-

- Book:

- Art and Anti-Racism in Latin America

- Published online:

- 19 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 277-304

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

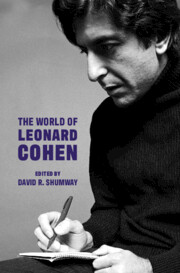

The World of Leonard Cohen

- Coming soon

-

- Expected online publication date:

- January 2026

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026

-

- Book

- Export citation

Copyright page

-

- Book:

- Ottoman Reform at Work

- Published online:

- 19 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp iv-iv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 2 - Petrarch’s Father, Brother, Son, and the Literary Life

-

- Book:

- Family, Vocation, and Humanism in the Italian Renaissance

- Published online:

- 18 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 18-62

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

maps

-

- Book:

- Peasants to Paupers

- Published online:

- 24 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp xviii-xviii

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

3 - Who Racializes? Exploring the Demographic Factors of Members of Congress Who Provide Racial Rhetorical Representation through an Intersectional Perspective

-

- Book:

- Black Voices in the Halls of Power

- Published online:

- 27 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 50-69

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

6 - Enclosing Property, Containing Envy

-

- Book:

- Peasants to Paupers

- Published online:

- 24 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 181-204

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

3 - Challenging Whiteness and Europeanness in Argentine Cultural Production

- from Part I - Art and Anti-Racism in the Nation

-

-

- Book:

- Art and Anti-Racism in Latin America

- Published online:

- 19 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 97-126

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Introduction

-

- Book:

- Ottoman Reform at Work

- Published online:

- 19 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 1-26

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 4 - World Literature and National Protectionism

-

- Book:

- Five Economies of World Literature

- Published online:

- 09 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 107-136

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 3 - Boccaccio and Narratives of Filial Freedom

-

- Book:

- Family, Vocation, and Humanism in the Italian Renaissance

- Published online:

- 18 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 63-112

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

9 - Coalfield Women’s Writing during the 1984–1985 Miners’ Strike

- from Part IV - Writing from Below

-

-

- Book:

- Writing Politics in Modern Britain

- Published online:

- 22 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 192-210

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Data and Methods Appendix

-

- Book:

- Black Voices in the Halls of Power

- Published online:

- 27 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 207-228

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Acknowledgements

-

- Book:

- Writing Politics in Modern Britain

- Published online:

- 22 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp xi-xii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Final Reflections

- from Part II - Artistic Practices, Racism and Anti-Racism

-

- Book:

- Art and Anti-Racism in Latin America

- Published online:

- 19 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 265-276

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Index

-

- Book:

- Writing Politics in Modern Britain

- Published online:

- 22 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 294-310

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contents

-

- Book:

- Family, Vocation, and Humanism in the Italian Renaissance

- Published online:

- 18 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp v-vi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

6 - Genres of British Fascist Writing

- from Part III - Perspectives from the Right

-

-

- Book:

- Writing Politics in Modern Britain

- Published online:

- 22 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 127-148

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Curated Conversation 1: Anti-Racist Art in the UK and Latin America

-

-

- Book:

- Art and Anti-Racism in Latin America

- Published online:

- 19 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 29-34

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation