Refine search

Actions for selected content:

28119 results in Astrophysics

The First Chapters of Our Cosmic History with JWST (IAU S391)

- Coming soon

-

- Expected online publication date:

- January 2026

- Print publication:

- 19 February 2026

-

- Book

- Export citation

Discoveries of Giant Radio Galaxies demonstrating the power of low surface brightness, wide-field imaging at high resolution

-

- Journal:

- Publications of the Astronomical Society of Australia / Volume 43 / 2026

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 19 January 2026, e012

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

A census of double-peaked Lyman-α emitters in MAGPI: Classification, global characteristics, and spatially resolved properties

-

- Journal:

- Publications of the Astronomical Society of Australia / Volume 43 / 2026

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 19 January 2026, e021

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

STORMY: A real-time triggering framework using Yamagawa solar spectrograph for active solar emission observations with the MWA

-

- Journal:

- Publications of the Astronomical Society of Australia / Volume 43 / 2026

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 13 January 2026, e011

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Built-in precision: Improving cluster cosmology through the self-calibration of a galaxy cluster sample

-

- Journal:

- Publications of the Astronomical Society of Australia / Volume 43 / 2026

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 12 January 2026, e003

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Perhaps there is no brown dwarf desert? A study of sub-stellar companions with Gaia DR3

-

- Journal:

- Publications of the Astronomical Society of Australia / Volume 43 / 2026

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 12 January 2026, e010

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

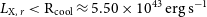

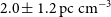

The life of central radio galaxies in clusters: AGN-ICM studies of eRASS1 clusters in the ASKAP fields

-

- Journal:

- Publications of the Astronomical Society of Australia / Volume 43 / 2026

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 06 January 2026, e001

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Radio frequency interference identification using eigenvalue decomposition for multi-beam observations

-

- Journal:

- Publications of the Astronomical Society of Australia / Volume 43 / 2026

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 02 January 2026, e008

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

The Deeper, Wider, Faster programme’s first DECam optical data release

-

- Journal:

- Publications of the Astronomical Society of Australia / Volume 43 / 2026

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 29 December 2025, e009

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Can high-redshift AGN observed by JWST explain the EDGES absorption signal?

-

- Journal:

- Publications of the Astronomical Society of Australia / Accepted manuscript

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 26 December 2025, pp. 1-21

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- Export citation

Using binary population synthesis to calculate the yields of low- and intermediate-mass binary populations at low metallicity

-

- Journal:

- Publications of the Astronomical Society of Australia / Volume 42 / 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 23 December 2025, e168

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

The Parkes observatory pulsar data archive

-

- Journal:

- Publications of the Astronomical Society of Australia / Volume 42 / 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 23 December 2025, e169

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

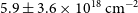

Discovery of the redback millisecond pulsar PSR J1728–4608 with ASKAP

-

- Journal:

- Publications of the Astronomical Society of Australia / Volume 43 / 2026

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 23 December 2025, e007

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

26 - Cosmological Radiative Transfer

- from Part Four - Ions and Photons in the Cosmos

-

- Book:

- Quasar Absorption Lines

- Published online:

- 17 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 18 December 2025, pp 1021-1052

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Foreword

-

- Book:

- Quasar Absorption Lines

- Published online:

- 17 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 18 December 2025, pp xv-xx

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Part Five - Analyzing Quasar Spectra

-

- Book:

- Quasar Absorption Lines

- Published online:

- 17 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 18 December 2025, pp 1053-1054

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

11 - High Ionization Metal-Line Absorbers

- from Part Two - Intervening Absorbers

-

- Book:

- Quasar Absorption Lines

- Published online:

- 10 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 18 December 2025, pp 347-410

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

6 - 21-cm Absorption

- from Part Two - Intervening Absorbers

-

- Book:

- Quasar Absorption Lines

- Published online:

- 10 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 18 December 2025, pp 167-186

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Part Four - Ions and Photons in the Cosmos

-

- Book:

- Quasar Absorption Lines

- Published online:

- 17 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 18 December 2025, pp 813-814

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Part Two - Intervening Absorbers

-

- Book:

- Quasar Absorption Lines

- Published online:

- 10 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 18 December 2025, pp 83-84

-

- Chapter

- Export citation