Introduction

The Acceptance of Cosmetic Surgery Scale (ACSS) (Henderson-King & Henderson-King, Reference Henderson-King and Henderson-King2005) is a 15-item instrument designed to measure the degree to which respondents accept the use of cosmetic surgery to enhance physical appearance. It is comprised of three subscales that assess acceptance of cosmetic surgery for personal psychological benefits, acceptance for social reasons, and the extent to which individuals would consider having cosmetic surgery.

The ACSS has been used and validated in numerous countries. Samples have spanned a wide range of ages both within and across studies, with participants as young as mid-teens and into older adulthood. Many studies have included both women and men as well as some degree of ethnic and cultural diversity. The scale has been used extensively by researchers, both in its entirety and separate subscales, to study attitudes about cosmetic surgery generally and individuals’ interest in having cosmetic surgery, as well as the relationship between cosmetic surgery acceptance and other body-related constructs such as body image, body-esteem, and sociocultural attitudes regarding appearance. Both correlational and experimental studies have utilized the ACSS to examine whether a wide array of social and individual difference factors, such as materialism and social media use, are predictive of, or influence, cosmetic surgery attitudes (e.g., Henderson-King & Brooks, Reference Henderson-King and Brooks2009; Walker et al., Reference Walker, Krumhuber, Dayan and Furnham2021).

Development

As the 1990s saw an increase in cosmetic surgery procedures, theorists and researchers became more interested in understanding the factors that were driving people’s seemingly greater acceptance and consideration of cosmetic surgery. Empirical research required valid and reliable measures of individuals’ attitudes and interest in cosmetic surgery, and the ACSS (Henderson-King & Henderson-King, Reference Henderson-King and Henderson-King2005) was developed to fill that need. We aimed to produce a scale that would capture individuals’ interest in pursuing cosmetic surgery to enhance their own physical appearance. However, since personal interest in having cosmetic surgery may or may not be consistent with individuals’ more general attitudes toward the practice (e.g., someone may be completely disinterested in having cosmetic surgery themselves, and yet have a positive attitude about the use of cosmetic surgery), we also sought to tap attitudes about the more general use of cosmetic surgery to enhance attractiveness.

Our focus was on two broad motives for having cosmetic surgery: intrapersonal (to feel better about oneself) and social (to be more attractive to others, perhaps for relationship or career purposes). Scale development began with a set of 26 items and was reduced for conceptual and statistical reasons to 15 items. Exploratory factor analyses revealed a three-component model with five items loading on each of the Intrapersonal, Social, and Consider factors, and all 15 items loading on a single unrotated factor. The scale demonstrated strong convergent validity, discriminant validity, and test-retest reliability. Of note to potential users of the scale, evidence regarding validity also pointed to the importance of distinguishing between social and intrapersonal aspects of cosmetic surgery acceptance as the two subscales differed in terms of their correlates. These findings reveal meaningful differences between these two aspects of cosmetic surgery attitudes; thus, researchers are advised to consider whether hypotheses regarding cosmetic surgery acceptance apply similarly across all aspects of acceptance.

Administration and Timing

The ACSS can be administered as a paper-and-pencil instrument or in an online format. In its entirety, the ACSS is completed in under five minutes by most respondents.

Factor Structure and Invariance

Research using exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses has consistently supported the three-factor structure in Western societies. However, in non-Western societies a two-factor structure (i.e., Social/Consider and Intrapersonal) has consistently been found (Swami et al., Reference Swami, Campana, Ferreira, Barrett, Harris and Tavares2011; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Alleva and Mulkens2020). The lack of invariance across cultures may reflect how people in individualist and collectivist societies view the self in relation to others. Occasionally, researchers have estimated error correlations for items within each subscale to achieve the best fit. As noted above, Henderson-King and Henderson-King (Reference Henderson-King and Henderson-King2005) found that all ACSS items could be combined into a single score, and this has been supported by numerous researchers.

Researchers have examined invariance of the ACSS across factors such as gender, age, education level, and body weight. Women tend to be more accepting of cosmetic surgery for intrapersonal reasons, and more likely to consider having cosmetic surgery, than men. Some have found that men are more accepting of cosmetic surgery for social reasons than women. Furthermore, the relationship between gender and scores on the Social and the Consider subscales may be moderated by a variety of individual difference variables (e.g., possible selves, Henderson-King & Henderson-King, Reference Henderson-King and Henderson-King2005).

Evidence of Reliability

Research has consistently reported excellent reliability for the overall score and for each subscale with Cronbach alphas ranging from the low .80s to mid .90s. Test-retest reliability for the subscales ranges from .62 to .82 for a 3-week administration window (Henderson-King & Henderson-King, Reference Henderson-King and Henderson-King2005).

Evidence of Validity

There is considerable evidence supporting construct validity. Overall acceptance (total ACSS score) is positively related to body appreciation (Swami et al., Reference Swami, Hwang and Jung2012; although, see Wu et al., Reference Wu, Alleva and Mulkens2020), body shame, life satisfaction, internalization of cultural beauty standards, facial appearance concerns (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Alleva and Mulkens2020), and perceived pressure for physical perfection (Meskó & Láng, Reference Meskó and Láng2021). Also, interventions designed to reduce cosmetic surgery acceptance can, at least temporarily, lower overall acceptance (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Mulkens, Atkinson and Alleva2024).

Regarding the ACSS subscales, there is evidence that scores on Consider are positively associated with attitudes toward makeup use, body dissatisfaction, and the internalization of sociocultural attitudes toward appearance (Henderson-King & Henderson-King, Reference Henderson-King and Henderson-King2005; Meskó & Láng, Reference Meskó and Láng2021; Stefanile et al., Reference Stefanile, Nerini and Matera2014) and negatively associated with appearance-esteem (Henderson-King & Henderson-King, Reference Henderson-King and Henderson-King2005) and body appreciation (Meskó & Láng, Reference Meskó and Láng2021). Scores on both the Intrapersonal and Social subscales have been positively associated with attitudes toward makeup use and fear of becoming unattractive (Henderson-King & Henderson-King, Reference Henderson-King and Henderson-King2005), appearance-related pressures and internalization of appearance pressures (Meskó & Láng, Reference Meskó and Láng2021; Stefanile et al., Reference Stefanile, Nerini and Matera2014), body dissatisfaction (Stefanile et al., Reference Stefanile, Nerini and Matera2014), and body shame (Henderson-King & Henderson-King, Reference Henderson-King and Henderson-King2005). However, only scores on the Social subscale are negatively related to appearance-esteem, social-esteem, and body appreciation (Henderson-King & Henderson-King, Reference Henderson-King and Henderson-King2005; Meskó & Láng, Reference Meskó and Láng2021). All of the subscales have consistently been found to be unrelated to general self-esteem, weight dissatisfaction, and performance self-esteem.

Scale Instructions and Items

Please indicate how much you agree or disagree with the following statements using the scale below.

1 = Disagree a lot; 2 = Disagree somewhat; 3 = Disagree a little; 4 = Neutral; 5 = Agree a little; 6 = Agree somewhat; 7 = Agree a lot.

Items:

1. It makes sense to have minor cosmetic surgery rather than spending years feeling bad about the way you look.

2. Cosmetic surgery is a good thing because it can help people feel better about themselves.

3. In the future, I could end up having some kind of cosmetic surgery.

4. People who are very unhappy with their physical appearance should consider cosmetic surgery as one option.

5. If cosmetic surgery can make someone happier with the way they look, then they should try it.

6. If I could have a surgical procedure done for free, I would consider trying cosmetic surgery.

7. If I knew there would be no negative side effects or pain, I would like to try cosmetic surgery.

8. I have sometimes thought about having cosmetic surgery.

9. I would seriously consider having cosmetic surgery if my partner thought it was a good idea.

10. I would never have any kind of plastic surgery.

11. I would think about having cosmetic surgery in order to keep looking young.

12. If it would benefit my career, I would think about having plastic surgery.

13. I would seriously consider having cosmetic surgery if I thought my partner would find me more attractive.

14. Cosmetic surgery can be a big benefit to people’s self-image.

15. If a simple cosmetic surgery procedure would make me more attractive to others, I would think about trying it.

Scoring

Reverse score Item 10. Calculate mean scores for each of the subscales and the Overall Acceptance score as follows (replacing Item 10 with Item 10 reverse scored):

Intrapersonal Subscale: Items 1, 2, 4, 5, and 14;

Social Subscale: Items 9, 11, 12, 13, and 15;

Consider Subscale: Items 3, 6, 7, 8, and reverse-scored Item 10;

Overall Acceptance: all items, using the reverse-scored Item 10 in place of Item 10.

Abbreviations

There are no abbreviated versions of the ACSS. However, some researchers have administered only a single subscale of the ACSS. Though original evidence of validity and reliability data were based on the administration of the ACSS in its entirety, subsequent studies have provided evidence of good validity and reliability for the Consider subscale when administered separately.

Permissions

Scholars wishing to use an unmodified version of the ACSS (either in its entirety or individual subscales) have permission to do so without contacting the authors. Those intending to modify items or use individual items from the scale should contact Eaaron Henderson-King (henderse@gvsu.edu) or Donna Henderson-King (hendersd@gvsu.edu) for permission. Those wishing to translate the ACSS have permission to do so. As noted above, the ACSS is available free of cost; use of the scale should not be undertaken for financial gain.

Copyright

Elsevier holds the copyright for the publication in which the ACSS originally appeared (Henderson-King & Henderson-King, Reference Henderson-King and Henderson-King2005). Sample items may be included in research articles to provide explication of the scale and its subscales; however, authors who wish to publish the entire scale in its originally published format should contact Elsevier for permission: www.elsevier.com/authors/permissions-request/journal-permissions-form.

Additional Information for Users

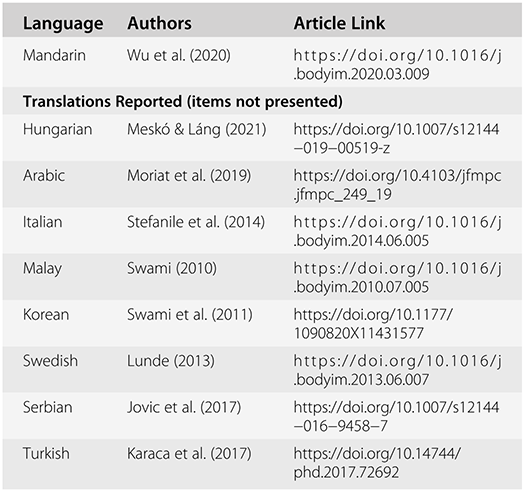

Those reporting on their use of the ACSS should cite the authors of the scale, Henderson-King and Henderson-King (Reference Henderson-King and Henderson-King2005). Users of a translated version of the ACSS (Table 1.1), please cite both the authors of the original version and the authors of the translated version.

| Language | Authors | Article Link |

|---|---|---|

| Mandarin | Wu et al. (Reference Wu, Alleva and Mulkens2020) | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2020.03.009 |

| Translations Reported (items not presented) | ||

| Hungarian | Meskó & Láng (Reference Meskó and Láng2021) | https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144−019−00519-z |

| Arabic | Moriat et al. (2019) | https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_249_19 |

| Italian | Stefanile et al. (Reference Stefanile, Nerini and Matera2014) | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2014.06.005 |

| Malay | Swami (2010) | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2010.07.005 |

| Korean | Swami et al. (Reference Swami, Campana, Ferreira, Barrett, Harris and Tavares2011) | https://doi.org/10.1177/1090820X11431577 |

| Swedish | Lunde (2013) | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2013.06.007 |

| Serbian | Jovic et al. (2017) | https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144−016−9458−7 |

| Turkish | Karaca et al. (2017) | https://doi.org/10.14744/phd.2017.72692 |

Any additional questions about the ACSS and its use may be directed to Eaaron Henderson-King (henderse@gvsu.edu) or Donna Henderson-King (hendersd@gvsu.edu).