Refine search

Actions for selected content:

22661 results in Cambridge Companions

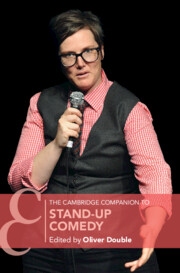

The Cambridge Companion to Stand-Up Comedy

-

- Published online:

- 21 August 2025

- Print publication:

- 04 September 2025

3 - Ulysses

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to James Joyce

- Published online:

- 14 August 2025

- Print publication:

- 21 August 2025, pp 47-63

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

4 - Reading Ulysses Historically

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to James Joyce

- Published online:

- 14 August 2025

- Print publication:

- 21 August 2025, pp 64-83

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contents

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to British Postmodern Fiction

- Published online:

- 07 August 2025

- Print publication:

- 21 August 2025, pp v-vi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 15 - British Fiction Beyond Postmodernism

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to British Postmodern Fiction

- Published online:

- 07 August 2025

- Print publication:

- 21 August 2025, pp 240-254

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

8 - Joyce the European

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to James Joyce

- Published online:

- 14 August 2025

- Print publication:

- 21 August 2025, pp 136-152

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Figures

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to James Joyce

- Published online:

- 14 August 2025

- Print publication:

- 21 August 2025, pp vii-vii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

5 - De-Confusing Confession at Finnegans Wake

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to James Joyce

- Published online:

- 14 August 2025

- Print publication:

- 21 August 2025, pp 84-101

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

13 - Joyce and Nature

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to James Joyce

- Published online:

- 14 August 2025

- Print publication:

- 21 August 2025, pp 216-231

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Note on the Cambridge Companion to James Joyce, Third Edition

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to James Joyce

- Published online:

- 14 August 2025

- Print publication:

- 21 August 2025, pp xi-xi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Acknowledgements

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to British Postmodern Fiction

- Published online:

- 07 August 2025

- Print publication:

- 21 August 2025, pp xx-xx

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chronology

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to British Postmodern Fiction

- Published online:

- 07 August 2025

- Print publication:

- 21 August 2025, pp xi-xix

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

6 - Joyce’s Shorter Works

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to James Joyce

- Published online:

- 14 August 2025

- Print publication:

- 21 August 2025, pp 102-119

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Further Reading

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to British Postmodern Fiction

- Published online:

- 07 August 2025

- Print publication:

- 21 August 2025, pp 272-277

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

12 - Joyce and the Everyday

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to James Joyce

- Published online:

- 14 August 2025

- Print publication:

- 21 August 2025, pp 200-215

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 4 - The Geographies of British Postmodern Fiction

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to British Postmodern Fiction

- Published online:

- 07 August 2025

- Print publication:

- 21 August 2025, pp 66-81

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

11 - Sex and Sexuality

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to James Joyce

- Published online:

- 14 August 2025

- Print publication:

- 21 August 2025, pp 184-199

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 13 - Neo-Victorian Fiction

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to British Postmodern Fiction

- Published online:

- 07 August 2025

- Print publication:

- 21 August 2025, pp 206-223

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Copyright page

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to James Joyce

- Published online:

- 14 August 2025

- Print publication:

- 21 August 2025, pp iv-iv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Index

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to British Postmodern Fiction

- Published online:

- 07 August 2025

- Print publication:

- 21 August 2025, pp 278-286

-

- Chapter

- Export citation