Refine search

Actions for selected content:

90435 results in Archaeology

Economies of the Inca World

-

- Published online:

- 09 January 2025

- Print publication:

- 30 January 2025

-

- Element

- Export citation

“The dear little flower babe has arrived!”: Blade stones, cradles, and child warriors in Ancient Mesoamerica

-

- Journal:

- Ancient Mesoamerica / Volume 36 / Issue 1 / April 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 09 January 2025, pp. 1-13

-

- Article

- Export citation

ALHAMAT: analysing materiality of the Alhambra to elucidate the Nasrid dynasty's power in the Emirate of Granada

- Part of

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

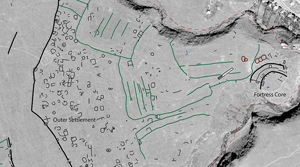

Mega-fortresses in the South Caucasus: new data from southern Georgia

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

The Late Bronze Age harbour of Pefkakia: evidence from transport containers suggests site's role

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Review of Valentina Vadi, Cultural Heritage in International Economic Law, Brill, 2023, 447 pages

-

- Journal:

- International Journal of Cultural Property / Volume 31 / Issue 3 / August 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 06 January 2025, pp. 386-390

-

- Article

- Export citation

Distorting history in the restitution debate. Dan Hicks’s The Brutish Museums and fact and fiction in Benin historiography – CORRIGENDUM

-

- Journal:

- International Journal of Cultural Property / Volume 31 / Issue 2 / May 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 06 January 2025, p. 226

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

The Ruins of Rome

- A Cultural History

-

- Published online:

- 02 January 2025

- Print publication:

- 06 February 2025

Acknowledgements

-

- Book:

- The Origins of Agriculture in the Bronze Age Indus Civilization

- Published online:

- 13 December 2024

- Print publication:

- 02 January 2025, pp xiv-xvi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Seven - Rice

-

- Book:

- The Origins of Agriculture in the Bronze Age Indus Civilization

- Published online:

- 13 December 2024

- Print publication:

- 02 January 2025, pp 114-134

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Index

-

- Book:

- The Origins of Agriculture in the Bronze Age Indus Civilization

- Published online:

- 13 December 2024

- Print publication:

- 02 January 2025, pp 349-354

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Tables

-

- Book:

- The Origins of Agriculture in the Bronze Age Indus Civilization

- Published online:

- 13 December 2024

- Print publication:

- 02 January 2025, pp xiii-xiii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contents

-

- Book:

- The Origins of Agriculture in the Bronze Age Indus Civilization

- Published online:

- 13 December 2024

- Print publication:

- 02 January 2025, pp vii-x

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Three - Laying the Groundwork

-

- Book:

- The Origins of Agriculture in the Bronze Age Indus Civilization

- Published online:

- 13 December 2024

- Print publication:

- 02 January 2025, pp 28-42

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

One - Introduction

-

- Book:

- The Origins of Agriculture in the Bronze Age Indus Civilization

- Published online:

- 13 December 2024

- Print publication:

- 02 January 2025, pp 1-13

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Twelve - Cropping Strategies and Seasonality

-

- Book:

- The Origins of Agriculture in the Bronze Age Indus Civilization

- Published online:

- 13 December 2024

- Print publication:

- 02 January 2025, pp 204-220

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Copyright page

-

- Book:

- The Origins of Agriculture in the Bronze Age Indus Civilization

- Published online:

- 13 December 2024

- Print publication:

- 02 January 2025, pp iv-iv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Ten - Beyond ‘Staples’

-

- Book:

- The Origins of Agriculture in the Bronze Age Indus Civilization

- Published online:

- 13 December 2024

- Print publication:

- 02 January 2025, pp 167-183

-

- Chapter

- Export citation