Refine search

Actions for selected content:

6950 results in Algorithmics, Complexity, Computer Algebra, Computational Geometry

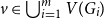

A special case of Vu’s conjecture: colouring nearly disjoint graphs of bounded maximum degree

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 33 / Issue 2 / March 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 10 November 2023, pp. 179-195

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

On oriented cycles in randomly perturbed digraphs

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 33 / Issue 2 / March 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 08 November 2023, pp. 157-178

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

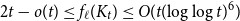

Mastermind with a linear number of queries

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 33 / Issue 2 / March 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 08 November 2023, pp. 143-156

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

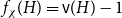

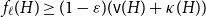

On the choosability of

$H$-minor-free graphs

$H$-minor-free graphs

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 33 / Issue 2 / March 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 03 November 2023, pp. 129-142

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Spanning subdivisions in Dirac graphs

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 33 / Issue 1 / January 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 20 October 2023, pp. 121-128

-

- Article

- Export citation

Many Hamiltonian subsets in large graphs with given density

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 33 / Issue 1 / January 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 02 October 2023, pp. 110-120

-

- Article

- Export citation

Intersecting families without unique shadow

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 33 / Issue 1 / January 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 02 October 2023, pp. 91-109

-

- Article

- Export citation

3 - Common Discrete Random Variables

- from Part II - Discrete Random Variables

-

- Book:

- Introduction to Probability for Computing

- Published online:

- 12 September 2023

- Print publication:

- 28 September 2023, pp 44-57

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

15 - Estimators for Mean and Variance

- from Part V - Statistical Inference

-

- Book:

- Introduction to Probability for Computing

- Published online:

- 12 September 2023

- Print publication:

- 28 September 2023, pp 255-264

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

References

-

- Book:

- Introduction to Probability for Computing

- Published online:

- 12 September 2023

- Print publication:

- 28 September 2023, pp 539-543

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Copyright page

-

- Book:

- Introduction to Probability for Computing

- Published online:

- 12 September 2023

- Print publication:

- 28 September 2023, pp iv-iv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

12 - The Poisson Process

- from Part IV - Computer Systems Modeling and Simulation

-

- Book:

- Introduction to Probability for Computing

- Published online:

- 12 September 2023

- Print publication:

- 28 September 2023, pp 210-228

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

24 - Discrete-Time Markov Chains: Finite-State

- from Part VIII - Discrete-Time Markov Chains

-

- Book:

- Introduction to Probability for Computing

- Published online:

- 12 September 2023

- Print publication:

- 28 September 2023, pp 420-437

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

20 - Hashing Algorithms

- from Part VI - Tail Bounds and Applications

-

- Book:

- Introduction to Probability for Computing

- Published online:

- 12 September 2023

- Print publication:

- 28 September 2023, pp 346-362

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Part VII - Randomized Algorithms

-

- Book:

- Introduction to Probability for Computing

- Published online:

- 12 September 2023

- Print publication:

- 28 September 2023, pp 363-418

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

8 - Continuous Random Variables: Joint Distributions

- from Part III - Continuous Random Variables

-

- Book:

- Introduction to Probability for Computing

- Published online:

- 12 September 2023

- Print publication:

- 28 September 2023, pp 153-169

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Part VIII - Discrete-Time Markov Chains

-

- Book:

- Introduction to Probability for Computing

- Published online:

- 12 September 2023

- Print publication:

- 28 September 2023, pp 419-538

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

10 - Heavy Tails: The Distributions of Computing

- from Part III - Continuous Random Variables

-

- Book:

- Introduction to Probability for Computing

- Published online:

- 12 September 2023

- Print publication:

- 28 September 2023, pp 181-197

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Preface

-

- Book:

- Introduction to Probability for Computing

- Published online:

- 12 September 2023

- Print publication:

- 28 September 2023, pp xv-xxi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Dedication

-

- Book:

- Introduction to Probability for Computing

- Published online:

- 12 September 2023

- Print publication:

- 28 September 2023, pp v-vi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation