Refine search

Actions for selected content:

6974 results in Algorithmics, Complexity, Computer Algebra, Computational Geometry

Part II - The Combinatorial Geometry of Flat Origami

-

- Book:

- Origametry

- Published online:

- 06 October 2020

- Print publication:

- 08 October 2020, pp 73-74

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

10 - Folding Manifolds

- from Part III - Algebra, Topology, and Analysis in Origami

-

- Book:

- Origametry

- Published online:

- 06 October 2020

- Print publication:

- 08 October 2020, pp 191-216

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Index

-

- Book:

- Origametry

- Published online:

- 06 October 2020

- Print publication:

- 08 October 2020, pp 330-332

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

13 - Rigid Foldings

- from Part IV - Non-flat Folding

-

- Book:

- Origametry

- Published online:

- 06 October 2020

- Print publication:

- 08 October 2020, pp 256-289

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Dedication

-

- Book:

- Origametry

- Published online:

- 06 October 2020

- Print publication:

- 08 October 2020, pp v-vi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contents

-

- Book:

- Origametry

- Published online:

- 06 October 2020

- Print publication:

- 08 October 2020, pp vii-x

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

12 - Rigid Origami

- from Part IV - Non-flat Folding

-

- Book:

- Origametry

- Published online:

- 06 October 2020

- Print publication:

- 08 October 2020, pp 231-255

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

1 - Examples and Basic Folds

- from Part I - Geometric Constructions

-

- Book:

- Origametry

- Published online:

- 06 October 2020

- Print publication:

- 08 October 2020, pp 11-30

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

9 - Origami Homomorphisms

- from Part III - Algebra, Topology, and Analysis in Origami

-

- Book:

- Origametry

- Published online:

- 06 October 2020

- Print publication:

- 08 October 2020, pp 181-190

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Origametry

- Mathematical Methods in Paper Folding

-

- Published online:

- 06 October 2020

- Print publication:

- 08 October 2020

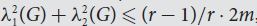

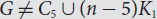

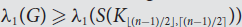

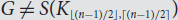

Eigenvalues and triangles in graphs

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 30 / Issue 2 / March 2021

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 28 September 2020, pp. 258-270

-

- Article

- Export citation

Finding tight Hamilton cycles in random hypergraphs faster

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 30 / Issue 2 / March 2021

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 23 September 2020, pp. 239-257

-

- Article

- Export citation

Maker–Breaker percolation games I: crossing grids

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 30 / Issue 2 / March 2021

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 15 September 2020, pp. 200-227

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- Export citation

Triangle-degrees in graphs and tetrahedron coverings in 3-graphs

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 30 / Issue 2 / March 2021

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 09 September 2020, pp. 175-199

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- Export citation

Hamiltonian Berge cycles in random hypergraphs

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 30 / Issue 2 / March 2021

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 08 September 2020, pp. 228-238

-

- Article

- Export citation

Dirac’s theorem for random regular graphs

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 30 / Issue 1 / January 2021

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 28 August 2020, pp. 17-36

-

- Article

- Export citation

Resilience of the rank of random matrices

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 30 / Issue 2 / March 2021

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 28 August 2020, pp. 163-174

-

- Article

- Export citation

Breaking bivariate records

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 30 / Issue 1 / January 2021

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 18 August 2020, pp. 105-123

-

- Article

- Export citation

Monochromatic cycle partitions in random graphs

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 30 / Issue 1 / January 2021

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 14 August 2020, pp. 136-152

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- Export citation

Many disjoint triangles in co-triangle-free graphs

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 30 / Issue 1 / January 2021

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 14 August 2020, pp. 153-162

-

- Article

- Export citation