Introduction

The database contains 131 cases of non-intervention, which means that for a majority (62.68%) of the population of cross-border cases examined in this study, there is no evidence of direct government interference through either bounded or unbounded intervention. Yet, in a small number of cases, the target state may have obviated the need for such behavior by engaging in internal intervention. In other words, the state actively fosters an alternative domestic merger or acquisition for the vulnerable company, in the hope of precluding the completion, and in some cases the initiation, of the foreign takeover it believes to threaten its power and/or survival (i.e., national security).

Fostering a better understanding of both these forms of state behavior is important, as each one has a potentially significant impact on the validity of the theory proposed in Chapter 1. This chapter is organized as follows. Part I looks at the dynamics behind non-intervention, including: (1) a discussion of the value of negative cases for hypothesis testing, (2) an examination of two key instances of non-intervention, (3) an analysis of the population of non-intervention cases, and (4) observations on the mitigating circumstances that may cause states to pursue this strategy over others. Part II examines the phenomenon of internal intervention. This section provides a more detailed discussion of the nature of such behavior and its relationship to traditional understandings of internal balancing in international relations theory, and concludes with a detailed case study.

Part I: Non-Intervention

Non-Intervention, Negative Cases, and Hypothesis Testing

Instances of non-intervention serve as “negative cases” for the primary hypothesis. If the basis of this hypothesis is that a high presence of either economic nationalism or geopolitical concerns can explain the motivation behind unbounded and bounded government intervention into cross-border M&A, then one would expect the majority of non-intervention cases to be characterized by either a lack, or very low levels, of these factors. The cases that provide the best test of the hypothesis, however, will be those in which “the dog did not bark;” in other words, those cases in which one would expect bounded or unbounded intervention, based on the presence of high levels of economic nationalism in the target state and geopolitical competition between the parties, but this did not occur.

Selecting negative cases for the purpose of hypothesis testing is a particularly difficult task in international relations theory. Too often, scholars choose to ignore the proverbially quiet dog, rather than become mired in methodological difficulties. In order to obviate that potential quagmire, the author has chosen to utilize insights from two of the most highly respected approaches to this issue.

First, the next section briefly examines the two most relevant non-intervention cases, chosen on the basis of insights from Mahoney and Goertz's “Possibility Principle” (Mahoney & Goertz Reference Mahoney and Goertz2004; see Skocpol Reference Skocpol and Skocpol1984). Fundamental to this approach is a belief that negative cases should be selected on the basis that they exhibit similar values on the independent variables to the positive cases, and that a positive outcome was, as a result, “possible” in these cases (Mahoney & Goertz Reference Mahoney and Goertz2004, 653–4). Thus, each of the cases examined in this part of the chapter could have resulted in a positive outcome – i.e., in bounded or unbounded intervention, because of the presence of a high level of economic nationalism and/or geopolitical competition – but did not. The lack of intervention, expected by the primary hypothesis in these cases, thus requires explanation. It should be noted that the approach of these scholars has been adapted slightly due to the probabilistic nature of the hypotheses in this book and the use of continuous independent variables (see Appendix F for a full description of how this was achieved).

The subsequent section employs an alternative approach to negative case selection that supports the inclusion of all cases, rather than limiting cases on the basis of the possibility of positive outcomes. This approach contends that all cases, both negative and positive, within a well-defined population should be used for hypothesis testing. The fundamental point is “that if researchers define the population carefully and appropriately, each case in the population contributes to causal inference and is therefore useful” (Seawright Reference Seawright2002).1 This argument would seem to be especially true in this study, where there may be additional circumstances that affect a state's choice not to intervene in a given case. While they may be beyond the bounds of the primary hypothesis, such conditions are important to an understanding of the overall theory of non-military internal balancing of this type, and may provide important insights for future research and testing. For, though it is not feasible or desirable to include detailed case studies of all 131 cases of non-intervention, it is possible to make some general observations about interesting trends that occur within that population.

Relevant Negative Cases

This section aims to confirm the accuracy of the hypothesis against the hardest negative case tests that could be raised against it. In each case, a non-intervention outcome results despite the apparent presence of the independent variables hypothesized to motivate intervention. Yet, the fundamental assumption of the primary hypothesis is that these factors cannot have a true effect unless the deal is seen to pose a real or perceived threat to national security. In the sectors examined in this study, the lack of such a real or perceived threat is actually quite rare when these two factors are present at extremely high levels; but it can happen, and in those rare instances where it does, one must turn to qualitative analysis to understand what appears to be a deviation from the hypothesis. Once that is done, it is quite clear that the primary hypothesis can be confirmed.

Case 8: CGG/Veritas

The French geophysical services and software business Compagnie Générale de Géophysique (CGG) announced on September 5, 2006 that it had agreed to acquire the American seismic data services company Veritas DGC. The deal was completed on January 1, 2007 without ostensible US government intervention.

One might have initially expected intervention in the transaction, because it fulfills certain criteria of the primary hypothesis. On the surface, the case appears structurally identical to the Alcatel/Lucent case of the same year. It involves a French company acquiring a US company in a strategic sector. The US government was exposed to the same degree of economic nationalism domestically, and was dealing with the same level of geopolitical tensions with France. In fact, it was this similarity of environment, and the presence of motivating factors for intervention, which led CGG and Veritas immediately and voluntarily to file the acquisition for review with CFIUS.

Yet, in the Alcatel/Lucent case, there was an unprecedented level of bounded intervention on the part of the US government. In this case, there was no intervention of which the public was made aware. How, then, can we explain the difference in government strategy in these cases, when the levels of economic nationalism and geopolitical competition are ostensibly the same?

The answer is simple, but can only be found through a qualitative examination of the case itself. Despite the presence of these broad factors, no national security issues specifically attenuated the takeover of this particular company. CFIUS wrote a letter to Veritas on November 16, 2006 confirming that it “had concluded its [preliminary thirty-day review], having found no national security issues sufficient to warrant further investigation” (Veritas 2006, 29). From Veritas’ filing with the SEC, it also seems safe to assume that neither company was asked to modify the conditions of the transaction by either CFIUS or the US President (Veritas 2006, 298). CFIUS does not, of course, make the details of its deliberations public. So it is difficult to determine exactly why the takeover of Veritas did not raise any major flags, despite the fact that seismic data are generally important for oil exploration and for the military, which uses it, for example, to monitor compliance with bans on nuclear warhead tests. When asked, one equity research analyst pointed out that it was “presumably” because “either nothing material in terms of state security contracts or use of their technical capacity by US forces” existed or remained within Veritas (Interview 2008c). In other words, no proprietary technology was at risk in the transaction that would negatively affect US defense, and the purchase of Veritas did not threaten US control over any kind of finite resource.

It should also be noted that the control variables in this case did not affect the intervention outcome. First, though the US government did investigate the deal in accordance with the Hart–Scott–Rodino Antitrust Improvements Act, it did not find any competition concerns related to the takeover (Zephyr 2007e). Second, interest groups did not play a significant role in affecting the US government's stance on the takeover. The shareholders and boards of directors of both companies supported the takeover, as was required for its successful completion, on the basis that the economic rationale was sound, significant “complementarities” were present, and new opportunities for growth would be created (Zephyr 2007e). No major interest groups – shareholders, unions, political, or others – emerged in strenuous opposition to the merger. Yet, none of these facts seems to have swayed the US government's decision not to intervene in this case.

Thus, though the broad independent factors of geopolitical competition and economic nationalism were present, no specific national security concerns were raised by the deal, making government intervention unlikely, rather than likely. This is important, because it helps to highlight the fact that the primary hypothesis assumes geopolitical competition and economic nationalism will only lead to intervention in foreign takeovers when either a genuine, or at least a plausible, national security concern is raised by the proposed takeover. As mentioned in Chapter 1, a government requires the presence of such a concern that it can point to as the reason for that intervention. Such a concern makes geopolitical competition relevant, and economic nationalism acceptable, in motivating government response. The lack of intervention in this case therefore confirms the primary hypothesis.

Case 9: JP Morgan/Troika Dialog

Rumors circulated the markets and newswires on August 28, 2006 that the US investment bank JP Morgan was considering an acquisition of the Russian investment bank Troika Dialog. As Western banks were seeking to expand into Moscow's markets, Troika's position as one of the older non-state-owned banks made it a fairly attractive takeover target. Troika's suitors included not only JP Morgan, but also the US bank Citigroup, the Swiss investment bank Credit Suisse, and even the Russian government-owned Vneshtorgbank (VTB) (see Prince & Baer Reference Prince and Baer2006; Busvine Reference Busvine2006).

The Russian government did not ostensibly intervene in this case, despite the presence of geopolitical competition between the US and Russia, and of economic nationalism within Russia in 2006. Indeed, at this time, geopolitical tension between the US and Russia was increasing over a series of issues, ranging from US involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan to the initial failure to agree upon the bilateral US–Russian protocol needed for Russia's bid for accession to the WTO (see e.g., Aslund Reference Aslund2006; Rutenberg & Kramer Reference Rutenberg and Kramer2006). Furthermore, there was also a fairly high degree of anti-globalization sentiment in Russia in 2006 (see IMD 2007b).2

Once again, however, there was no direct national security concern related to this potential takeover, despite the fact that it was occurring in a sector generally considered to be strategic. Troika's independence from the Russian government gave it the opportunity during that time to search for the economic option for its company's future from a purely fiduciary outlook, to the point where it was able eventually to reject the state-owned VTB's offer on the basis that the price was too low (see Busvine Reference Busvine2006). In the banking and financial services sector, an independent company is unlikely to be seen as an issue of national security unless (1) it is a national champion, (2) it is fundamental to the health and/or identity of the national economy, or (3) times of severe economic crisis require the active retention of capital and banking resources within the domestic economy. As Troika did not meet any of these conditions in the generally optimistic investment and economic climate of 2006, it was unlikely that the Russian government would intervene. Even economic nationalist sentiment in Russia at this point was focused on national champions in the natural and basic resource sectors, and was unlikely to spill over to the financial services sector in order to protect a company that was not really seen as a national champion, and thus not necessarily a matter of national concern.

Finally, neither interest group pressure nor competition concerns seem to have played a role in Russia's decision not to intervene in this case. Neither factor emerged as an issue in response to the rumored takeover. They were not even mentioned by reporters, analysts, members of government, or the companies themselves in their discussions of the potential deal.

Once again, this case confirms the primary hypothesis. Government intervention did not occur – despite the general presence of the motivating factors of economic nationalism in the target state and general geopolitical competition between the countries involved – because there was no national security concern inherent to the takeover in question. It should also be noted that this particular proposed foreign takeover never made it past the “rumor” stage. This is because the management of the company, which had a controlling interest in Troika, decided not to sell on the basis that it desired to stay an independent Russian bank, and therefore protected itself temporarily from a potential takeover by affecting a large employee stock purchase (Syedain Reference Syedain2007). In this way, the company itself also voluntarily obviated the true issue. The intervention outcome might have been different if this had not happened, and if the Russian government had decided to identify Troika as a national champion that it was necessary to protect on national security grounds.

Overview of the Negative Case Population

The purpose of this section is to provide a more general analysis of the negative case population within the dataset.

Primary Hypothesis

The quantitative testing of the dataset in Chapter 2 supported the primary hypothesis. The result of MNLM I demonstrated that a state was less likely to intervene in a foreign takeover, in an unbounded or bounded manner, when geopolitical tensions and economic nationalism were low.

The notion that low levels of geopolitical friction between states make direct intervention less likely seems borne out by an examination of the population of negative cases in the dataset. MNLM I confirmed that state A was significantly less likely to use unbounded or bounded forms of intervention (i.e., it was more likely not to intervene) when state B was a member of the same security community. In fact, 79% of the non-intervention cases took place within the security community context, and of that 79%, 83% of cases resulted in a completed and unmitigated deal. (This observation is striking when compared to the fact that of the 65% of unbounded intervention cases occurring within the confines of a security community, 73% were successfully prevented from resulting in any deal at all.) For the 21% of non-security community cases of no intervention, MNLM III showed that state A was significantly less likely to intervene if its military power was greater relative to that of state B.

Furthermore, it seems clear that direct intervention is unlikely to occur when levels of economic nationalism are very low. MNLM I demonstrated that, across all cases, intervention was significantly less likely when pro-globalization sentiment in state A was high. At the same time, MNLM II proved that the significance of this relationship, between low-levels of economic nationalism and non-intervention, was even stronger for deals that took place within a security community.

The phenomenon of “non-intervention” may, however, have some additional dynamics, which will be useful for understanding the implications of non-military internal balancing, and which may provide avenues for future research. It is important to note that these observations do not contradict the primary hypothesis proposed here, but may instead add to its explanatory power.

Mitigating Circumstances Identified in the Population of Negative Cases

It appears that, in each of the cases in the dataset where geopolitical competition concerns and economic nationalism are exceptionally high (whether quantitatively or qualitatively examined), non-intervention usually is the result only when the exact deal in question can still not be perceived as posing an unacceptable problem for national security. However, there also seem to be six “mitigating circumstances” that emerge from this population, which appear to ameliorate issues/deals that could potentially be seen as national security concerns – if the state wants to make an argument to that effect.

1. Bid from an Institutional Investor

A state may be more open to a foreign takeover, despite the presence of the hypothesized motivating factors, when the acquirer is an institutional investor. An institutional investor may be generally defined as “a bank, mutual fund, pension fund, or other corporate entity that trades securities in large volumes” (FINRA 2008). However, the true nature of the institutional investor is captured by the fact that it must be a “third-party professional,” whose purpose is to act as a “fiduciary investment capital allocation organization” on behalf of a client (Interview 2008d).3

The data provide some interesting facts regarding this type of investor. Of all the 209 cases in the database, forty-nine involved potential acquirers that may be classed as institutional investors. The government of the target company in question chose not to intervene in thirty-nine (or 80%) of these forty-nine cases. Only ten resulted in some form of government action. Half of these remained at the level of low-bounded intervention. Of the remaining five cases, three involved high-bounded interventions, and only two led to unbounded interventions on the part of the state. This means that only 10% of institutional investor bids resulted in these less routine, and more intense, forms of government intervention.

This tendency toward non-intervention into foreign takeovers that are proposed by institutional investors indicates that governments may perceive such actors as less threatening than other types of potential acquirers. This might be because institutional investors are usually considered to be pure market actors with a fiduciary responsibility to act impartially in the best interest of their clients, i.e., to be motivated by financial, rather than political, gain.

Granted, some institutional investors may be more political than they seem at first glance. Indeed, SWFs, state banks, and other state investment funds qualify as institutional investors, despite their connection to the state. The rise in power and quantity of SWFs over the last decade has been frequently discussed as having a potentially political impact, for example, because, though many continue to be innocuous market actors, some are viewed as potentially having political motivations for their investment choices. For example, one hedge-fund analyst pointed out that some SWFs very simply “have a more political mandate from inception (like Russia, Libya, etc.) than others” (Interview 2008d). He argued that, based on “the criteria of: (1) sources and target recipients of funds, (2) mandate and oversight of capital allocation, and (3) forms of investments, [one could] array a spectrum of public/funded institutions…from the most like a profit-maximizing fund manager to the least” (Interview 2008d). This range would appear as follows:

(1) pension/retirement trusts for public employees, taxpayer entitlements’ trusts, etc., (2) sovereign wealth funds, (3) regulatory trusts (e.g., the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation), (4) the World Bank [and other] multi-lateral lenders (e.g., the Inter-American Development Bank and the European Investment Bank), (5) the International Monetary Fund, and (6) Central Banks.

Banks that are state-owned, controlled, and run, he argued, are much more difficult to categorize (Interview 2008d).

Thus, while there is a clear connection between non-intervention and acquirers that are institutional investors, the highly varied nature of this type of investor suggests that further research into this correlation is required.

2. Desired Exit

A state may also be more open to a foreign takeover, despite the presence of the hypothesized motivating factors, when it involves the purchase of a company that has actively and willingly placed the “for sale” sign in its window, i.e., when the takeover resolves a company's desire to voluntarily exit the marketplace. There are many reasons for a “desired exit” of this nature. The company may no longer be viable, it may have difficulty competing in a particular sector, it may have been put up for sale by a parent company that thinks its margins are too low or by a parent company that needs to concentrate its resources elsewhere. Whatever makes the target company pursue such a strategy, it does seem to have a distinct and ameliorating effect on intervention.

Across the full database of 209 cases, twenty-seven can be classified as a desired exit. In twenty-one (or 78%) of those twenty-seven cases, the target company's government chose not to intervene in the takeover. Of the remaining six cases, there were zero instances of unbounded intervention, only one of high-bounded intervention, and the remaining five cases involved only low-bounded intervention. Thus, there seems to be a very clear trend that desired exits only rarely lead to intervention, and that when they do, the intervention will tend to be of the more moderate low-bounded variety.

There is a fairly simple explanation for this behavior. If a company desires an exit – because it is no longer a viable concern or because its parent company cannot afford to operate it, or no longer wishes to do so, for whatever reason – then the company will need to find either a domestic or an international buyer. If that company is vital to national security, say because it is the sole producer of an important piece of military equipment, then the state has two preferred options:

1. It can hope for a domestic company to step in and take over the target, or it can actively facilitate such a domestic merger through internal intervention, as discussed in Part II of this chapter. (Remember that in this scenario, the state's actions are classified as non-intervention because it has not intervened directly to stop or alter a proposed foreign takeover from a specific company.)

2. It can allow the target to be taken over by a foreign company, but modify the deal in its favor in an effort to protect its national security interest in the company. Clearly, this may not be the preferred option for some states, but it will likely be a much better alternative than the complete failure or disappearance of the company, the continued function of which it perceives to be vital to national security. In this case, the state would rather have the company bought and continue to operate, than go out of existence all together.

The Chinese government, for instance, did not intervene in 2006 when the US networking equipment manufacturer 3Com Corporation took over the JV company it had originally established in China with the Chinese telecommunications equipment manufacturer Huawei. This is an extremely interesting example, because when Huawei attempted to acquire 3Com only a year later, CFIUS found significant national security concerns involved in the transaction, and the US government eventually sought to stop the proposed transaction through unbounded intervention. Yet, in the earlier case where the Chinese JV was the target, the Chinese government did not react as the American government later did. This was because, despite tension between the US and China, and China's stated efforts to protect its strategic telecommunications companies from takeover, Huawei (and China) had already gained the technology it originally sought through the JV, and wanted to leave the project, making its sale a desired outcome.

3. Fear of a Bidder from a Less Friendly Country

Another circumstance that might influence a government's decision to either not intervene, or to do so at only the low-bounded level, is when the proposed foreign acquirer is seen as coming from a “friendlier” country than that from which alternative possible bidders might originate. Again, this remains true even in the presence of perceived national security issues heightened by the presence of geopolitical competition and economic nationalism. While such an occurrence is rarer, and more difficult to identify and code on a consistent basis, than the previous mitigatory circumstances examined here, its effect on intervention outcomes is undeniably clear.

One need only look, for example, at cases like the takeover of Arcelor by the Indian steel manufacturer Mittal Steel. Arcelor was another steel manufacturer, based in Luxembourg, but really seen as a French company. Mittal's bid for Arcelor was rejected out of hand twice in early 2006, primarily because of virulent resistance from European leaders, who argued the takeover would be dangerous for the security of the region. Here, there was a definitively strong presence of economic nationalism, as well as geopolitical competition concerns aroused by India's rising status as an economic power. Yet, these leaders did a dramatic about face when the Russian company Severstal emerged as an alternative bidder. Despite the initial unbounded intervention by the French government, the deal was eventually allowed to proceed unaltered, rather than have Arcelor's steel production come under Russian control. This is not surprising, given the fact that Russia already controlled a large proportion of this particular resource, and had recently proved its willingness to use control over another resource (i.e., natural gas) as a means to demonstrate its power over its neighbors.

4. National Security Concerns Previously Addressed

Governments are also highly unlikely to engage in high-bounded or unbounded intervention when the national security concerns inherent to a particular target company's takeover have already been addressed in some way. For example, this may mean that the foreign acquirer has already signed a stringent national security agreement (or the equivalent thereof) with the target state, or that the companies may have already agreed among themselves to divest or “black box” the division of the company that is identified as related to national security.

This particular mitigating circumstance may not have as great an effect in those target countries where economic nationalism is present in extremely high levels, as the governments of such states may not wish to recognize the fact that a national security concern has already been addressed, but may instead wish to raise it for more political reasons. Yet, in those instances where geopolitical competition is the main motivating factor of intervention, unbounded or high-bounded intervention is less likely when the national security issues have already been dealt with in some way.

In other words, if the companies have arranged to “take care” of the national security-related aspects of the deal before the formal bid is made, or as part of the merger agreement, and have done so to the satisfaction of the target state, intervention is unlikely. This is often true even in the face of moderately high levels of economic nationalism or geopolitical tension.

Alternatively, if the companies have not made such arrangements, but the acquirer has a proven track record of acquisitions in strategic sectors in the target country, and has previously signed a national security agreement4 or similar contract with the target state that obligates it to adhere to certain security precautions and laws, and which can be adapted to the current takeover, then low-bounded intervention will ensure this adaptation is made. In such a case, though the general geopolitical relationship between the states involved may be good, the deal is still identified as having implications for national security and power that must be dealt with. As discussed in Chapter 5, this was the case when the UK's BAE Systems took over United Defense Industries (UDI) in the US. BAE Systems had a subsidiary, BAE Systems North America, which was to be used for the takeover, and which already had a series of stringent national security agreements with the US government, as well as a track record of honoring them. Thus, though the deal involved the takeover of a premier US defense company with multiple government contracts, the US only needed to engage in low-bounded intervention to update these agreements. It stands to reason, however, that if the previous agreements signed by the acquirer can be perceived to cover the new proposed takeover, no intervention will be considered necessary.

5. Deal Strengthens Industrial Base/National Security

Another mitigating circumstance that will increase the chance of non-intervention or low-bounded intervention is if a deal is actually considered to be advantageous to national security, or is perceived to strengthen national security and/or the defense industrial base in some way (see Grundman & Roncka Reference Grundman and Roncka2006; Moran Reference Moran1993). For example, Grundman and Roncka argue that there are twenty possible variables that might affect a company's chance of survival of the US government review process of foreign takeovers, and seven of these are related to whether or not the deal can be seen as contributing to the health of the defense industrial sector (Grundman & Roncka Reference Grundman and Roncka2006, 8).5 A deal might, for example, increase the competition among companies in the production of a good considered vital to national security (e.g., semiconductors). Alternatively, it could provide the state in question with access to a resource that it desperately needs (e.g., uranium or natural gas).

Such considerations will, probably, be more common when the potential acquirer is a close ally, for it is unlikely that a bid originating from an “unfriendly” country would be perceived as contributing positively to the target state's defense sector. Furthermore, there may already be some degree of integration of the defense industrial base among close allies, and this may be viewed as preferable on the basis that it widens the scope of competition, and thus enhances the opportunities for the development of new technologies, while offering the possibility of lowering the price of such advances.

It is important to note, however, that alliance relationships are unlikely to matter if a deal is still considered to pose a significant national security risk or to have a highly negative impact on the defense industry. This partly explains, for example, why the US was willing to allow the takeover of UDI by BAE Systems, but would be unlikely to allow the same company to take over a business like L-3 Communications. UDI arguably needed to be revitalized. The situation would be viewed differently for a company like L-3, however, which holds sensitive government contracts integral to national security, and the takeover of which would appear to have no immediate benefit to the health of the defense communications and technology sector.

6. State Pursues the Internal Intervention Option

Finally, one very particular instance should be mentioned in which economic nationalism and/or geopolitical competition concerns are present, along with a clear national security concern, but state A still does not intervene in the deal itself. This is when the state decides instead to pursue a course of “internal intervention” in order to counter the threat posed by the deal. (It should also be noted here that if a deal (Z) supports state A's efforts toward internal intervention in another case (Y), then state A will obviously not intervene in deal Z.) The dynamics behind the strategy of internal intervention are fully explained in Part II of this chapter.

Secondary Hypothesis

The secondary hypothesis posits that the type of intervention chosen by the government of state A will affect the deal outcome. If this is true, we would expect to find that, barring unforeseen circumstances, deals would go through unaltered if government intervention did not occur.

Once again, the numbers seem to support this hypothesis (see Figure 31).6 Of the 131 cases of no intervention in the database, 102 deals (or 77.86%) were completed, all with ostensibly no changes or modifications. (See Figure 32 for a breakdown of deal outcomes by sector in all cases of non-intervention.)

| Intervention Type | Deal Outcome | Number of Cases |

|---|---|---|

| No Intervention | Deal | 102 |

| Changed Deal | 0 | |

| No Deal | 29 |

Figure 31 Non-intervention and the secondary hypothesis

| Sector | Industries | Completed Deals (Total = 102) | Failed Deals (Total = 29) | All Non-Intervention Deals (Total = 131) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oil & Gas | Oil & Gas Producers | |||

| Oil Equipment, Services & Distribution | 24 | 5 | 29 | |

| Basic Resources | Aluminum | |||

| Steel | 9 | 2 | 11 | |

| Industrials | Aerospace | |||

| Defense | ||||

| Marine Transportation | 7 | 4 | 11 | |

| Telecommunications | Fixed-Line Telecommunications | |||

| Mobile Telecommunications | ||||

| Satellite Telecommunications | 18 | 2 | 20 | |

| Utilities | Electricity | |||

| Gas Distribution | ||||

| Multi-Utilities | ||||

| Water | 15 | 6 | 21 | |

| Financials | Investment Services (Stock Exchanges) | 18 | 5 | 23 |

| Technology | Software | |||

| Computer Hardware | ||||

| Semiconductors | ||||

| Telecommunications Equipment | 11 | 5 | 16 |

Note: Sector and Industry titles sourced from www.icbenchmark.com.

Figure 32 Non-intervention cases: outcome breakdown by sector

Only twenty-nine (or 22.14%) of the cases of no intervention still resulted in a failed deal. Some unforeseen factors account for this. First, one of the companies involved may have had a change of heart or have been forced to pull out, either for financial reasons or because of intractable shareholder opposition. Second, the government of state A might have made it clear to the parties that it would intervene in the deal if it went any further, without allowing that information to become public. Finally, state A might not have had to intervene in the deal itself in order to create an effective barrier to its completion. Instead, the state may have obviated the issue by choosing what I have termed the internal intervention option.

Part II: Internal Intervention

There are times when market analysts become aware that a company is susceptible to a potential takeover long before any potential “suitors” emerge. In such circumstances, the company in question, and the state in which it is domiciled (state A), may have a fairly long window of opportunity in which to assess its options, and to determine who might seek to buy the vulnerable target. If the company is viewed as a strategic asset, or a national champion, the government of state A may decide to monitor the situation closely.

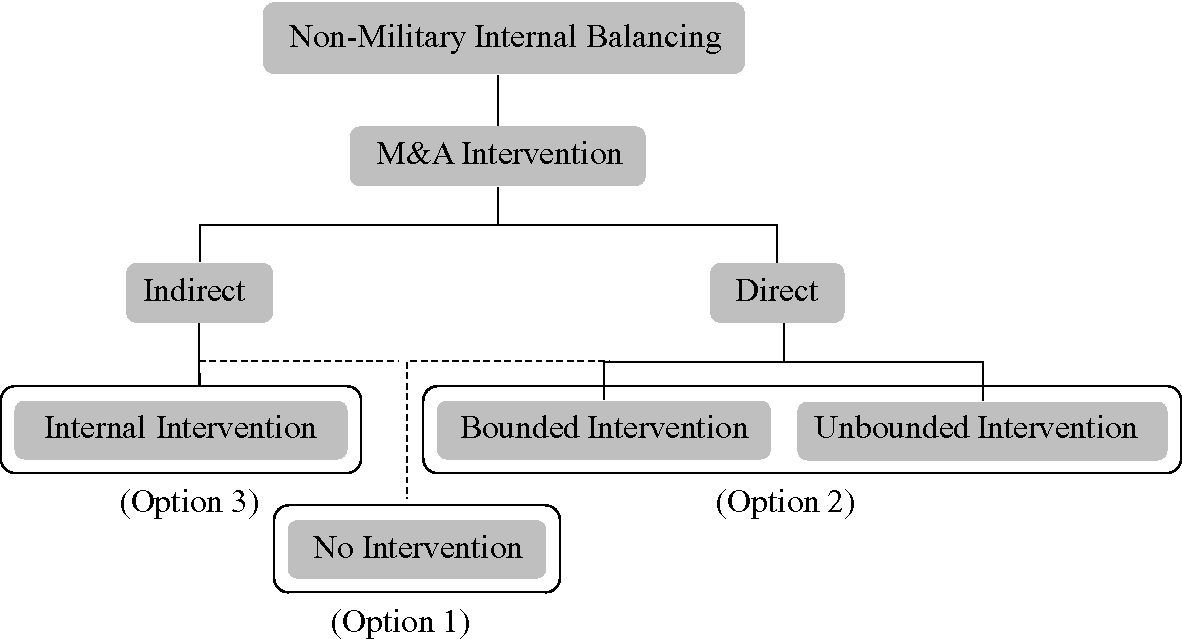

If a foreign bidder then emerges for the vulnerable target, or if it is believed one will do so in the near future, the government of state A has three options (see Figure 33). (1) If the foreign bidder is not perceived as threatening, for one of the reasons already discussed, the government may decide not to intervene. (2) If it is believed that the potential foreign acquirer, and the deal that they propose, poses a potential threat to national security, state A may choose to intervene directly into the proposed foreign takeover through a strategy of either unbounded or bounded intervention, once the deal has solidified. These first two choices were analyzed in the primary and secondary hypotheses proposed in this work. (3) Alternatively, when faced with such a threat, state A may choose to engage in a strategy of internal intervention. As will be shown, this strategy does not involve direct intervention into an unwelcome proposed takeover, but instead utilizes more indirect tools to accomplish a similar goal. It is, therefore, a strategy that can be used before a formal bid is made by the potential foreign acquirer, and even before a rumored suitor has been verified, in order to preempt the need for direct intervention, while still obviating the outcome the state believes to be undesirable. Internal intervention may also occur later in the bidding process, or even in tandem with the forms of direct intervention analyzed earlier. As a result, it provides the state with a greater degree of latitude and strategic flexibility.

Figure 33 Non-military internal balancing: M&A intervention options

As defined here, internal intervention can take one of three forms. First, it can mean that the government proactively seeks, encourages, and then supports a domestic company to act as an alternative bidder for the vulnerable target. Such a company would then act as a “white knight:” a welcomed and friendly bidder that would fend off a hostile (and, in this case, foreign) bid by either acquiring or merging with the target. The Gaz de France (GdF)/Suez case study that follows examines this form of intervention, as it is the most interesting and useful for our discussion of this particular form of non-military internal balancing. (In that case, a French government-sponsored “white knight,” GdF, stepped in to merge with the French power company Suez, which was feared to be susceptible to an unwanted foreign takeover.)

Second, the government might aggressively encourage domestic investors and/or companies to purchase a large stake in the target in order to promote a high level of cross-shareholding. Such a strategy can help a vulnerable entity to defend itself from a takeover later, assuming that those new domestic shareholders will vote against the unwanted potential foreign takeover bid. The German government, for example, was active in promoting cross-shareholding between Porsche and Volkswagen (VW) (one of its national champions) in order to prevent VW from being acquired by a foreign company. Indeed, the promotion of cross-shareholding to protect strategic sectors is popular in a number of European and Asian countries, such as France, Italy, Spain, and Japan.

Third, state A might promote or support a merger (that it would normally block on competition grounds) of two weaker domestic companies in order to create a national champion. Such a national champion would not only be less susceptible to a foreign takeover, but would also, arguably, provide other economic benefits. Russia's government, for example, is believed to have played a strong hand in the consolidation of the Russian aluminum companies Rusal and Sual in order to prevent these companies from becoming liable to a future foreign takeover. After the Rusal/Sual tie-up, it then supported a further merger with Glencore (of Switzerland) in order to create “the world's biggest aluminum producer” (Pavliva Reference Pavliva2007), but only on the understanding that the majority of the new company would remain in Russian hands. Oleg Deripaska, the owner of the newly merged entity United Company Rusal, has openly said that he is even prepared to “‘give up’ the company to the state if the Russian government asked for it,” because he “[does not] separate [him]self from the state” and “[has] no other interests” (Pavliva Reference Pavliva2007). Such statements clearly indicate that the company remains under the definitive influence and control of the Russian government.

Internal Intervention as a Tool of Non-Military Internal Balancing

Internal intervention is, therefore, one potential means of non-military internal balancing. It allows the state to protect those sectors it deems vital to national security from foreign ownership and control, when such an outcome would be potentially detrimental to its relative power position and rank, or to its future survival. For example, internal intervention offers one possible way to obviate a potential foreign takeover that would place a highly sensitive industry, or vital and scarce resource, in the hands of a known political/military competitor and/or rising power. Ally and foe alike, therefore, might be targeted by such a form of intervention, as both have the potential to change or challenge a state's relative power position in a world where economic, political, and military power are inextricably linked, though challenges to state survival are obviously most likely to come from previously identified foes.

Like any other tool of non-military internal balancing, internal intervention is a strategy that allows the state to maintain (or maximize) the economic and military power necessary for state survival, and is a response to a specific threat – real and/or perceived – to relative power. It, too, like the types of intervention discussed in the previous chapters, qualifies as form of internal balancing, because it is a “move to increase economic capability” (Waltz Reference Waltz1979, 118) as part of the wider effort to preserve and/or maximize power in response to a challenge to that power. It is non-military in nature, because this balancing tool is also chosen for its ability to maintain the greater meta-relationship at stake between the states involved, as it is unlikely ever to lead to a truly negative or irreversible disruption in such a relationship.

On first appearance, this internal form of intervention may appear to be the most similar to the “economic component” of traditional internal balancing as defined by Brawley (in Paul et al. Reference Paul, Wirtz and Fortmann2004). Yet, while it can be a tool connected to a direct “increase [in] military strength” (Waltz Reference Waltz1979, 118) or an “arms race” (see Brawley in Paul et al. Reference Paul, Wirtz and Fortmann2004, 85), it may also simply be part of a more general strategy that seeks to counter threats to other areas of economic power vital to a state's overall power, position, and long-term survival. The temporal frame and cadence of the internal intervention strategy may also be very different from more conventional forms of internal balancing. In other words, while internal balancing has traditionally been understood to be a response to an immediate, or near-term, threat to power, the type of intervention discussed here may be part of a strategy to balance a challenge to power that may not threaten survival for many decades to come.7

The author is not arguing that the dynamics behind internal intervention can be fully explained by the primary and secondary hypotheses posited earlier. Though the factors motivating the desire to intervene internally may be similar to those hypothesized to influence the direct forms (unbounded and bounded) of government intervention in most cases, there may be additional factors governing this particular type of state behavior under certain circumstances. It must be stressed here that internal intervention is an alternative to direct intervention into a cross-border acquisition, and its indirect nature may make it subject to other domestic political factors.

Furthermore, while all governments retain the right to engage in direct intervention (bounded or unbounded) against a takeover they deem threatening to their national security, not all governments are necessarily willing to engage in internal intervention, which is seen by some states as aggressively anti-free-market behavior. Other nations, however, such as Russia, France, Italy, Germany, and Spain, have been more open in their willingness to help vulnerable national champions find domestic saviors. Economic nationalism may therefore play a larger role in this type of intervention.

Either way, the case study that follows is meant only to explore the possibility that internal intervention may be motivated by the same factors of economic nationalism and geopolitical competition that have been found to have such a great effect on bounded and unbounded intervention. Remember that the primary hypothesis tested in the previous chapters is meant only to cover direct intervention into a foreign takeover. The purpose of this section, therefore, is simply to provide insights on the basis of the primary hypothesis, which should enable a better understanding of the relationship between internal intervention and other forms of non-military internal balancing, and should contribute to the formation of a more complete hypothesis governing such indirect forms of intervention in the future.

Case 10: GdF/Suez

The merger of the French energy companies Suez SA and Gaz de France (GdF) is one of the most striking examples of internal intervention over the last decade. Initiated as an effort by the French government to protect Suez from a hostile takeover by the Italian energy company Enel, the deal took over two years to complete, and pitted the French and Belgian governments against that of Italy. It stands as a testament to the lengths that a government will go to in order to fend off a foreign takeover it perceives as threatening, even before such a takeover is formally attempted. It also clearly demonstrates how state power can be employed, and balanced, though the market. An overview of this case is provided, as well as an examination of its connection to the factors examined in the primary hypothesis and a discussion of how it exemplifies balancing through internal intervention.

The Story

The saga began in the middle of February 2006, when it became clear that Enel was likely to place a bid for Suez in the near future. At this point, the CEO of Enel, Fulvio Conti, confirmed that his company might be interested in a hostile takeover of Suez, in order to gain control of the electricity assets held by its Belgian subsidiary Electrabel (Freeman Reference Freeman2006; Thornton Reference Thornton2006b). The company then released a statement on February 25, indicating it was considering different options for “expanding abroad,” and specifying France as one of the countries in which it was “examining…opportunities” (Enel 2006).

The reaction of the French and Belgian governments was immediate and forceful. On the very same day as Enel's press release, the French government took two major and definitive steps. The first was to take preventative action by actively fostering a domestic merger between Suez and GdF, which was still a French state-controlled entity. GdF was France's leading natural gas supplier at that time, and the combination would create a national champion whose size and ownership structure would be significantly strengthened against a foreign takeover (see e.g., Dempsey & Benhold Reference Dempsey and Bennhold2007; Ng Reference Ng2006). Concern over Suez's vulnerable position had already led Thierry Breton, the French Minister for Economy, Finance, and Industry, to ask in September 2005 that the companies “draft a merger plan” (Robin Reference Robin2006). Then, “less than one hour after Enel['s announcement]” on February 25, “the top management of Gaz de France and Suez met together with the French [Prime Minister] and approved a friendly merger between the two groups,” which would have the explicit “support of the French and Belgian governments” (Freeman Reference Freeman2006; Roden Reference Roden2006). The timing and speed of this official announcement sent a clear signal to any potential foreign bidders for Suez that the French government preferred a domestic partner for the company. This message was clearly received by Enel's CEO, who rightly called the action “a pre-emptive maneuver to shield the country's utilities from foreign takeovers” in general (Freeman Reference Freeman2006).

In the second step, the French government made it clear, through public statements and personal communication to the Italian government, that it would not allow Suez to be taken over by Enel specifically. The then Prime Minister of France, Dominique de Villepin, immediately called his “Italian counterpart Silvio Berlusconi to express his opposition to any Suez takeover” (Freeman Reference Freeman2006). Indeed, Villepin's opposition was vehement. He was widely reported to have said that a “hostile bid from Enel would be considered as an ‘attack on France’” (Chassany Reference Chassany2006, emphasis added). Such language is more than mere French rhetorical style, for it clearly shows that the French government considered the speculated bid to be a potentially serious threat to French economic and political power.

The Italian reaction to this position was equally pronounced. Berlusconi, for his part, initially requested “the French government to be impartial in the face of Enel's takeover bid” (International Herald Tribune 2006b). When it was apparent that that was not going to happen, the Italians’ frustration became more pronounced. The Italian government cancelled a meeting between its “Industry Minister Claudio Scajola…[and] his French counterpart Francois Loos to discuss energy and competition” (Freeman Reference Freeman2006). Scajola declared publicly that “the political and economic destiny of the European Union will be compromised if neo-protectionism prevails” (Freeman Reference Freeman2006). For, the Italian Minister, not surprisingly, viewed the French move as one of pure protectionism, despite the fact that there were obvious strategic implications for France of such a takeover (to be examined in detail later). Scajola's stance, however, was followed by some rather unfortunate rhetoric referencing World War I, which did not strengthen the Italian position in French eyes. Italy's Economic Minister Giulio Trementi stated on the same day: “We still have time to stop European Union states from building national barriers. If not, we risk the impact of August 1914” (International Herald Tribune 2006b). The (perhaps unintended) bellicosity of this statement only seemed to make the French more wary. The Italians also registered a formal complaint with the European Commission over the proposed combination of GdF and Suez, in an effort to have it stopped.

In the end, however, the French achieved the creation of a new national champion (now called GdF Suez), and the Italians were forced to back down. As will be discussed in greater detail shortly, a foreign takeover of Suez was unacceptable to France for reasons of both economic nationalism and geopolitics. Yet, as will also be examined, the threat was diffuse and not necessarily specific to Italy. An act of internal balancing through internal intervention was thus required, because it would strengthen the French position against this type of threat from any external actor. At the same time, France's overall relationship with Italy was not truly damaged. Despite the Italian government's official rhetoric and frustration, it was unlikely such a disagreement could permanently damage an otherwise healthy diplomatic relationship, and Italy was eventually mollified both politically and economically.

Setting the Stage: Geopolitics and Economic Nationalism

Both geopolitical considerations and economic nationalism played a strong role in motivating the French government's decision to intervene in this case. The following analysis will review the position of the companies within the framework of France's strong economic nationalism, while also showing that the country's reaction had important geopolitical underpinnings.

As one of the world's top diversified utilities companies, Suez provided a large proportion of the electricity, natural gas, water, and waste management services in France. This provision of vital resource and energy services made Suez of special interest to the French government at a time when many European countries were seeking to consolidate their control over the provision of domestic utilities.8 Competition in the recently liberalized European utilities market was (and has remained) fairly low, and Neelie Kroes, then European Commissioner for Competition Policy, made it a top priority to change that situation when she acceded to her post in 2004 (see Kroes Reference Kroes2008). Her push for legislation within the European Parliament introduced significant structural reforms to Europe's energy markets, and led to a race among European companies, and the governments that often controlled them, to consolidate control and resources before the proverbial “doors” were opened to further competition and new market entrants (Interview 2006; Scott Reference Scott2008).

At the same time, the French and Italian governments were made highly aware of the dangers of natural gas dependence. Just under two months before the proposed hostile takeover of Suez by Enel, Russia had flexed its geopolitical muscle through its control over natural gas resources. On January 1, 2006, the Russian state-controlled oil company Gazprom cut off natural gas supplies to the Ukraine for almost four days following an alleged dispute over a rise in prices. The Ukraine was believed to have fought back by siphoning gas from that headed to Europe (BBC 2006). Whether this was truly a case of “siphoning” or a result of other technical difficulties, the cut-off had a deep impact on Europe, which saw a significant reduction in its natural gas supplies. The French supply of Russian gas fell by 25–30%, and the Italian supply by 24% (BBC 2006), the true impact of which is understood when one recognizes that between 2006 and 2007, Russian natural gas exports accounted for 20% of French and 25% of Italian domestic consumption (EIA 2008b). The event seemed to impact deeply on both countries’ desire to gain access to alternative supplies of natural gas, as well as their desire to bolster their own domestic natural gas companies.

The specter of Russian control over natural gas not only helps explain Enel's initial search for foreign expansion opportunities, such as a Suez takeover, but was also a motivating factor for France's internal intervention throughout the duration of this case. By December 2006, Russia was threatening to take similar action against Belarus, which in turn threatened to siphon exports of Russian gas destined for Europe in retaliation (Osborn Reference Osborn2006). The dispute between Russia and the Ukraine over natural gas was revived in October 2007, and Russia again cut off supplies to the Ukraine in January 2009. Once more, whether intentionally or not, this caused a noticeable disruption in supply to continental Europe, demonstrating European concerns about Russia's control over the resource were well founded.

The French government, and the companies themselves, clearly saw the potential loss of strength in the natural gas sector as a source of geopolitical concern. The GdF/Suez merger prospectus clearly stated that the tie-up was largely motivated by the “greater geostrategic challenges associated with the security of European energy sources” (GdF Suez 2008). The primary problem was that

The European Union is currently dependant on imports for 55% of its natural gas needs. By 2020, it is estimated that imports will account for 85% of European Natural Gas requirements. Norway and two countries outside of Europe (Russia and Algeria) account for a significant share of current supplies and the future resources that will supplement those supplies are relatively concentrated in a few distant countries (particularly the Persian Gulf).

The Belgian government, whose country relied heavily on both Suez and GdF for its natural gas and electricity supplies, shared this concern. Suez's subsidiary Electrabel generated 92% of the electricity, and provided 70% of the natural gas, in Belgium (Roden Reference Roden2006). At the same time, GdF, through its subsidiary Segeo, owned one of the larger gas pipelines in Belgium. Thus, it was not particularly surprising that the Belgian state supported the proposed merger of GdF and Suez. It had no national champion of its own to support, but the proven relationship with the French companies was highly satisfactory, whereas the Italian company Enel was an unknown quantity.

This geopolitical competition over resources and economic power combined with high levels of economic nationalism in France to spur the vigorous response of the French government as a whole. The PepsiCo/Danone and Alcatel/Lucent cases demonstrate that economic nationalism was high in France during this period.9 Indeed, France has never been shy about its desire to protect its markets or its national champions through the stated policy of “patriotisme économique.” In this particular case, the European Commission specifically decried the use of “nationalist rhetoric” on the part of both the French and Italian governments (Times 2006). This case also came at a time when the French government had only recently announced its plan (in 2005) to protect the eleven sectors it deemed to be strategic, which included the energy sector. Furthermore, French Prime Minister de Villepin and Economic Minister Breton were consistently open about their desire to create a national champion that would have European reach through the merger of GdF and Suez.

The French government also ensured that the new “national champion” would remain under state control by taking a golden share in the newly formulated entity. A golden share is a special issue of stock that gives a government certain final veto powers over decisions made about the company in question. The Merger Prospectus of GdF Suez makes it clear that “the purpose of this golden share is to preserve the essential interests of France in the energy sector to ensure continuity or security of energy supplies” (GdF Suez 2008). The Prospectus also makes it clear that natural gas supplies were the primary energy concern of the French government in this case.10

It is also important to note that the geopolitical threat was more diffuse in this case than it was in the cases examined in previous chapters. There was likely some level of concern that Italy's natural gas sector would soon fall under greater Russian control, and therefore increase Europe's dependence on its supplies. This concern emanated from Russia's stated desire at that time to gain greater market share in Italy's gas distribution network. In general, however, it was not specific geopolitical tension with Italy, or a specific difference in the relative economic or political positions of France and Italy, that seems to have aroused French concern. Rather, it was the general concerns over France's economic position, and over its control of resources ahead of further deregulation by the European Commission, that were primarily at issue.

Alternative Explanatory Factors: Interest Group Presence and Competition Concerns

In the final analysis, neither interest groups nor competition concerns proved to be a significant factor in motivating French intervention in this case.

First, the French unions did not significantly affect the outcome of government intervention because, even though their opposition to the combination of GdF and Suez held up the completion of the merger, it never completely threatened to derail it. The French unions were vociferously against the GdF/Suez deal because it would mean the privatization of GdF and, thus, the loss of a number of employee protections and privileges (see e.g., ICEM 2006; International Herald Tribune 2008). GdF's unions initiated a brief strike against the proposed combination in June 2006 (Kanter Reference Kanter2006). They were also able to cause delays by requesting, through a court-stay, more time to review the deal before providing their official opinion on it (International Herald Tribune 2008). The outcome, however, was never placed in jeopardy by this action. This was because the “official opinion” required by the union under French law was only a legal formality for completion; the eventual negative opinion given by the unions did not (and was not expected to) stop the merger (International Herald Tribune 2008; Roden Reference Roden2008). Thus, while the French unions were not in favor of a GdF/Suez merger, they would probably have taken similar steps against any action that would have privatized GdF. Their opposition was not enough to affect the French government's decision.

Second, the powerful interest groups of the various shareholders in both companies that could have tried to block the deal did not do so, largely because they agreed with the French government on the threat posed by an Enel takeover. In the end, the boards and shareholders of both companies approved the merger in 2008. The major shareholders of Suez at the time were reported to be very close to the French government (Roden Reference Roden2006). Market analysts believed that when Suez shareholders voted to enact a “poison pill” against a potential Enel takeover in May 2006, their actions were politically motivated because of their proximity to the government (Roden Reference Roden2006). Even the shareholders of GdF (beyond the French state itself, which owned a majority of GdF stock), who were not threatened by a hostile foreign takeover, voted in favor of the deal. Perhaps it is most telling that they did so despite the fact that many equity research analysts believed the terms of the deal were unfavorable for GdF (Roden Reference Roden2006). Shareholders were thus largely in favor of the merger, and it seemed that this was a political response to the threat identified by the French government in a hostile Enel takeover of Suez.

Finally, though the European Commission was initially concerned by the potential effect of the deal on competition, these problems were eventually easily resolved by two small asset disposals. The European Commission decided to investigate the proposed merger of GdF and Suez to ensure that the combination was not detrimental to energy competition in Europe. This investigation was not conducted in response to Italy's objections that the deal was protectionist.11 In the end, the Commission “found that the deal would have anticompetitive effects in the gas and electricity wholesale and retail markets in Belgium and in the gas markets in France” (EU Commission 2006b). It determined, however, that these effects could be sufficiently assuaged by “structural remedies”: primarily “the divestiture of Distrigaz and SPE and Suez relinquishing its control of [the] Belgian network operator Fluxys” (EU Commission 2006b). These disposals were effected before the deal was completed in 2008, with Distrigaz being sold to the Italian energy company Eni, which may have provided some mollification for the Italian government. Furthermore, though the European Commission has generally sought to reduce the level of golden share ownership within member states, on the basis that it is anti-competitive in nature, the Commission did not object to the inclusion of a golden share for the French government in this particular case. In fact, the European Commissioner for the Internal Market and Services, Charlie McCreevy, wrote a letter to Minister Breton in September 2006, which “made clear that the decree establishing the golden share did not contain any ‘contentious’ elements that would merit legal action” on the part of Brussels (Buck et al. Reference Buck, Hollinger and Barber2006a). McCreevy reportedly attributed this to the fact that “France…managed to draft a decree that meets the Union's strict criteria for such special rights” (Buck et al. Reference Buck, Hollinger and Barber2006a).

Conclusions on GdF/Suez

High levels of economic nationalism and geopolitical competition in this case combined to make a foreign takeover of Suez identifiable with a threat to French power and security, and thus made intervention of some kind extremely likely. As the threat was more diffuse in this case, an act of internal balancing through internal intervention was required, because it would strengthen the French position against this type of threat not only from Italy, but also from any future external actor.

This act of internal intervention also appears consistent in cause, purpose, and effect with more traditional notions of internal balancing. The cause was an identified threat to security and power, here in the form of a foreign takeover of Suez. The purpose and effect were to counter that threat through internal economic and political measures, which would enhance the future French power position in this area. In this case, that was achieved by the support of a domestic merger that created a national champion (GdF Suez) that the French government could control through a golden share, and which increased the French position in the natural gas sector, enhancing not only France's national capabilities, but also its economic power.

At the same time, the goal of using non-military internal balancing to maintain the greater meta-relationship between the two countries was also achieved. Though Enel and the Italian government were forced to back down from their position, the overall relationship with Italy was not truly damaged. Despite the Italian government's official rhetoric and frustration, it was unlikely that such a disagreement could permanently damage an otherwise healthy diplomatic relationship, and they were eventually mollified both politically and economically.12

Conclusion

Part I of this chapter demonstrated that the primary and secondary hypotheses concerning the motivations behind direct intervention into foreign takeovers still hold once the population of non-intervention, or “negative,” cases has been examined. This was achieved by testing the hypotheses against the “hardest” negative case. In other words, against a case where the outcome was non-intervention despite the presence of the high levels of economic nationalism and/or geopolitical competition hypothesized to motivate intervention. Two such cases were examined, CGG/Veritas and JP Morgan/Troika Dialog, and it was demonstrated that, in each, a fundamental assumption of the hypothesis was missing: there was no real or perceived threat to national security, despite the fact that each case took place within what are normally considered to be strategic sectors. Though the lack of such a real or perceived threat is rare in such sectors, it does occur, and when that happens, non-intervention will tend to result, notwithstanding the presence of economic nationalism or geopolitical competition. This is because, in a generally liberal international economy, it is difficult to make a case for intervention without at least a plausible national security reason for doing so, and states are unlikely to pursue such a course of internal balancing unless they believe it to be necessary.

The first part of the chapter also posited that, in addition to the primary and secondary hypotheses, there may be six potentially mitigating circumstances that make non-intervention, or at least low-bounded intervention, a more likely outcome. These are when: (1) the proposed acquirer is an institutional investor; (2) the target is pursuing a desired exit from the marketplace; (3) state A fears a less friendly bidder will otherwise emerge; (4) the national security concerns inherent in the deal have been previously addressed; (5) the deal strengthens the defense industrial base; or (6) state A instead pursues the internal intervention option.

Part II of this chapter discussed the alternative, and indirect, form of non-military internal balancing that is internal intervention. The GdF/Suez case was examined to illustrate the possibility that economic nationalism and geopolitical competition also play a role in motivating this type of intervention. It was demonstrated that, at least in this case, the French government's actions seemed to be a clear internal balancing response to an imminent and identifiable external threat to French relative power and security. Though the purpose of this work was to test the hypothesis focused on direct forms of intervention (bounded and unbounded), this case study helped to demonstrate that the hypothesis does potentially hold for indirect (i.e., internal) intervention, and further testing might provide a fruitful avenue for future research.