Refine search

Actions for selected content:

90439 results in Archaeology

Assembling ancestors: the manipulation of Neolithic and Gallo-Roman skeletal remains at Pommerœul, Belgium

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

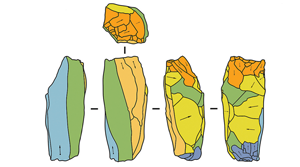

The Enderby Bark Shield: A New Model for the Ancient World

-

- Journal:

- Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society / Volume 90 / December 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 22 October 2024, pp. 205-228

- Print publication:

- December 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

RADIOCARBON CHRONOLOGY OF THE OCCUPATION OF THE SOUTHERN COAST OF NAYARIT, MEXICO

-

- Journal:

- Radiocarbon / Volume 66 / Issue 6 / December 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 21 October 2024, pp. 1753-1764

- Print publication:

- December 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

CONTEXTUAL REANALYSIS OF THE ARCHITECTURAL FORM AND SOCIO-ECONOMIC STATUS OF THE PANAGIA HOUSES AT MYCENAE

-

- Journal:

- Annual of the British School at Athens / Volume 119 / December 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 21 October 2024, pp. 337-361

- Print publication:

- December 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Intestinal Parasitic Infection in Roman Britain: Integrating New Evidence from Roman London

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Cretan Hieroglyphic

-

- Published online:

- 17 October 2024

- Print publication:

- 31 October 2024

-

- Book

-

- You have access

- Open access

- Export citation

Chapter 1 - The Discourse on Romanization in the Age of Empires

-

- Book:

- Decolonizing Roman Imperialism

- Published online:

- 03 October 2024

- Print publication:

- 17 October 2024, pp 15-50

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

References

-

- Book:

- Decolonizing Roman Imperialism

- Published online:

- 03 October 2024

- Print publication:

- 17 October 2024, pp 206-224

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Dedication

-

- Book:

- Decolonizing Roman Imperialism

- Published online:

- 03 October 2024

- Print publication:

- 17 October 2024, pp v-vi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Historical Intervention

-

- Book:

- Decolonizing Roman Imperialism

- Published online:

- 03 October 2024

- Print publication:

- 17 October 2024, pp 197-205

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Acknowledgements

-

- Book:

- Decolonizing Roman Imperialism

- Published online:

- 03 October 2024

- Print publication:

- 17 October 2024, pp viii-viii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 2 - Postcolonial Themes

-

- Book:

- Decolonizing Roman Imperialism

- Published online:

- 03 October 2024

- Print publication:

- 17 October 2024, pp 51-80

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 3 - Postcolonial Questions in the Age of Decolonization

-

- Book:

- Decolonizing Roman Imperialism

- Published online:

- 03 October 2024

- Print publication:

- 17 October 2024, pp 81-150

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Introduction

-

- Book:

- Decolonizing Roman Imperialism

- Published online:

- 03 October 2024

- Print publication:

- 17 October 2024, pp 1-14

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 4 - Towards a Paradigm Shift in the Age of Globalization

-

- Book:

- Decolonizing Roman Imperialism

- Published online:

- 03 October 2024

- Print publication:

- 17 October 2024, pp 151-196

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

A Ceramic Mould from Vindolanda: Craft and Industry along the Roman Frontier

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Index

-

- Book:

- Decolonizing Roman Imperialism

- Published online:

- 03 October 2024

- Print publication:

- 17 October 2024, pp 225-228

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contents

-

- Book:

- Decolonizing Roman Imperialism

- Published online:

- 03 October 2024

- Print publication:

- 17 October 2024, pp vii-vii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation