Refine search

Actions for selected content:

90439 results in Archaeology

Polyaenus (Strat. 8.23.5) and Caesar's British Elephant

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Copyright page

-

- Book:

- Decolonizing Roman Imperialism

- Published online:

- 03 October 2024

- Print publication:

- 17 October 2024, pp iv-iv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

The Engraved Slate Plaques of Late Neolithic and Copper Age Iberia: A Statistical Evaluation of the Genealogical Hypothesis

-

- Journal:

- European Journal of Archaeology / Volume 28 / Issue 1 / February 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 16 October 2024, pp. 43-60

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Rethinking Field School Delivery and Addressing Our Biases

-

- Journal:

- Advances in Archaeological Practice / Volume 12 / Issue 4 / November 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 16 October 2024, pp. 351-358

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

The Princely Burials of the Central Balkans in Context

-

- Journal:

- European Journal of Archaeology / Volume 27 / Issue 4 / November 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 16 October 2024, pp. 448-467

-

- Article

- Export citation

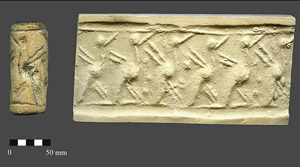

PLOMAT: plotting material flows of ‘commonplace’ Late Bronze Age seals in western Eurasia

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Investigating Heritage and Climate Change in the Coastal and Maritime Environments of Wales and Ireland: A Guide to the CHERISH Toolkit

-

- Journal:

- Advances in Archaeological Practice / Volume 12 / Issue 3 / August 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 15 October 2024, pp. 219-232

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- HTML

- Export citation

Assessing the quality of citizen science in archaeological remote sensing: results from the Heritage Quest project in the Netherlands

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Restitution of African Cultural Heritage: Revisiting Natural Law Concepts of Statehood and Property in the Context of Colonial Spoliation

-

- Journal:

- International Journal of Cultural Property / Volume 31 / Issue 1 / February 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 14 October 2024, pp. 102-123

-

- Article

- Export citation

A spectral cavalcade: Early Iron Age horse sacrifice at a royal tomb in southern Siberia

- Part of

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

LA CITTÀ DEL SILFIO. ISTITUZIONI, CULTI ED ECONOMIA DI CIRENE CLASSICA ED ELLENISTICA ATTRAVERSO LE FONTI EPIGRAFICHE By Emilio Rosamilia. Edizioni della Normale, Pisa, 2023. ISBN 9788876427367, pp. 453, 14 colour plates. Price: €40.00 (paperback)

-

- Journal:

- Libyan Studies / Volume 55 / November 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 07 October 2024, pp. 163-164

- Print publication:

- November 2024

-

- Article

- Export citation

Snake queens and political consolidation: How royal women helped create Kaan: A view from Waka’

-

- Journal:

- Ancient Mesoamerica / Volume 35 / Issue 3 / Fall 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 04 October 2024, pp. 766-783

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

The rise, expansion, and endurance of Kaanul: The view from northwestern Peten

-

- Journal:

- Ancient Mesoamerica / Volume 35 / Issue 3 / Fall 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 04 October 2024, pp. 689-707

-

- Article

- Export citation

In search of the serpent kings: From Dzibanche to Calakmul

-

- Journal:

- Ancient Mesoamerica / Volume 35 / Issue 3 / Fall 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 04 October 2024, pp. 822-838

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

New data, new interpretations: Dzibanche monuments through the lenses of a 3D scanner

-

- Journal:

- Ancient Mesoamerica / Volume 35 / Issue 3 / Fall 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 04 October 2024, pp. 708-725

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

The team for a new age: Naranjo and Holmul under Kaanu'l's sway

-

- Journal:

- Ancient Mesoamerica / Volume 35 / Issue 3 / Fall 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 04 October 2024, pp. 784-805

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Los gobernantes de la dinastía Kaanu'l en Dzibanché, Quintana Roo, México

-

- Journal:

- Ancient Mesoamerica / Volume 35 / Issue 3 / Fall 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 04 October 2024, pp. 806-821

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

The rise of the Kaanuˀl kingdom and the city of Dzibanche

-

- Journal:

- Ancient Mesoamerica / Volume 35 / Issue 3 / Fall 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 04 October 2024, pp. 726-747

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

An account of the kings of Kanu'l as recorded on the hieroglyphic stair of K'an II of Caracol

-

- Journal:

- Ancient Mesoamerica / Volume 35 / Issue 3 / Fall 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 04 October 2024, pp. 748-765

-

- Article

- Export citation